Abstract

Background

Reactive arthritis (ReA) consists of the classic clinical triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis generally occurring within 6 weeks of an infection, typically of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary systems. Cardiovascular manifestations of ReA and other members of the spondyloarthritis family have long been recognized.

Case Report

A 43-year-old male who was human leukocyte antigen-27 (HLA-B27)-positive and who had ReA for 19 years developed severe aortic insufficiency requiring aortic valve replacement. Typically, the onset of musculoskeletal symptoms precedes development of aortic insufficiency by many years. The average calculated from reported cases was 13 years, with a range from 4 days to 61 years. The mechanism by which the aortic valve leaflets become targets in HLA-B27-associated disease is unclear. At one point, interest developed as to whether the HLA-B27 allele was independently associated with lone aortic insufficiency, in the absence of clinical spondylitis. The preponderance of cardiac abnormalities in patients with HLA-B27-positive ReA has led to the suggestion that a genetic syndrome of the heart consisting of aortic insufficiency and conduction-system abnormalities exists, and has been dubbed the “HLA-B27-associated cardiac syndrome”. This case highlights the importance of recognizing the association between HLA-B27-associated spondyloarthritis and serious aortic valvular complications.

Conclusion

Clinicians should maintain a high suspicion for aortic insufficiency in patients with ReA, including a low threshold for echocardiographic evaluation. A heightened awareness can lead to earlier identification and potential avoidance of fatal events in these patients.

Keywords: reactive arthritis, aortic insufficiency

Introduction

Reactive arthritis consists of the classic clinical triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis generally occurring within 6 weeks of an infection, typically of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary systems. It is believed that reactive arthritis is an immune-mediated inflammatory reaction in the joints, conjunctiva, and urethra following a bacterial infection. Several causative pathogens have been proposed, including Chlamydia, Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter; however, attempts to culture these organisms from affected joint fluid have proven difficult [1].

Cardiovascular manifestations of reactive arthritis (ReA) and other members of the spondyloarthritis family have long been recognized. Mallory is credited with initially recognizing the association between aortic insufficiency and ankylosing spondylitis in 1936 [2]. It was then widely recognized in the 1960–1970s that patients with ReA are also at risk for developing aortic insufficiency [3–8].

Case Report

The patient, a 43-year-old male airline pilot diagnosed with ReA in 1984 was incidentally found to have a cardiac murmur consistent with aortic insufficiency (AI) in July 2003. He had a previous murmur diagnosed in 1987 that was not consistent with AI, but this new murmur was suspicious for AI. His initial presentation in 1984 was with urethral discharge, presumed to be due to a Chlamydial infection. In the subsequent 6 months, he developed bilateral knee and foot pain, as well as dactylitis involving his toes. At no point did he describe ocular involvement. He was diagnosed with reactive arthritis and found to be positive for HLA-B27.

The patient’s disease was well controlled initially with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. However, over the course of the ensuing 19 years, he developed several recurrences of his arthritis. In 1988, he developed severe pain bilaterally in his feet and knees, as well as involvement of his right Achilles tendon with enthesitis. The patient underwent therapeutic arthrocentesis which showed inflammatory fluid with no evidence of infection or crystalline disease. He subsequently required treatment with indomethacin and tolmetin for less than a year with resolution of symptoms. In 1994, he developed bilateral knee effusions which responded to treatment with sulfasalazine. At that point, he was initiated on prophylactic minocycline. His third flair in 2002 required treatment with leflunomide before resolution. In 2003, following administration of several vaccines including a tetanus booster, he noted recurrent symptoms in both knees. At this point, he was restarted on sulfasalazine, and per his request, minocycline and azithromycin were also initiated.

The patient was first noted to have a heart murmur in 1987, but it was thought to be benign in nature. An echocardiogram performed 10 years later (1997) as part of a Federal Aviation Administration physical examination showed mild mitral regurgitation. It was not noted until routine physical examination in July 2003 that he had a murmur consistent with aortic insufficiency. The patient was asymptomatic and in excellent physical condition. Physical examination was remarkable for a blood pressure of 150/35 in both arms. Carotid pulses were increased in volume with rapid runoff. Cardiac auscultation revealed an absent S2 at the right upper sternal border and a III/VI long decrescendo diastolic murmur heard best at the left lower sternal border with end-diastolic accentuation heard best over the left ventricular apex (Austin Flint murmur). Water hammer pulses were present in the upper extremities and Hill’s sign was present.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm at 66 beats/min, evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy, and left axis deviation consistent with left anterior fascicular block. An echocardiogram performed following this 2003 examination showed aortic insufficiency and normal left ventricular systolic function. Within 3 months, a repeat echocardiogram revealed severe aortic insufficiency with a trileaflet aortic valve that moved as a bicuspid valve due to a commissural fusion. Also noted was severe mitral regurgitation despite a structurally normal mitral valve (suggesting mitral annular dilation as the cause of regurgitation), mild left ventricular dilation as well as concentric hypertrophy, mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 40–45%, and mild aortic root dilation (diameter 4.2 cm).

Given the declining left ventricular systolic function of the patient’s left ventricle, despite the absence of clinical symptoms, it was recommended that the patient have his aortic valve surgically replaced. Intraoperatively, the aorta was not subjectively dilated but was noted to be thickened. The aortic valve leaflets were also found to be thickened, rubbery, and retracted. It was noted in the operating room that following replacement of the aortic valve, the degree of mitral regurgitation dropped dramatically. Five years later, the patient remains symptom-free, with normal follow-up examinations and echocardiograms.

Discussion

The literature review was conducted via a pubmed search using the terms “reactive arthritis and aortic insufficiency” and “reiter’s arthritis and aortic insufficiency.” Articles written in languages other than English were excluded. The references in these papers were then cross-referenced to identify any further case reports. Some articles are in themselves reviews of the existing literature; in these instances, every effort was made to identify the original articles. In ten instances, the original articles were unable to be identified (primarily coming from the papers by Good [8], and Zvaifler and Weintraub [9]). This search yielded 49 reported cases of patients with ReA who developed AI as a complication of the disease [2–29]. Next, articles that reported length of time between diagnosis with ReA and onset of AI were identified. In some review articles, only the mean time elapsed between ReA diagnosis and AI diagnosis was reported; in those cases, the mean time was weighed by a factor of the number of cases when calculating overall mean length of elapsed time.

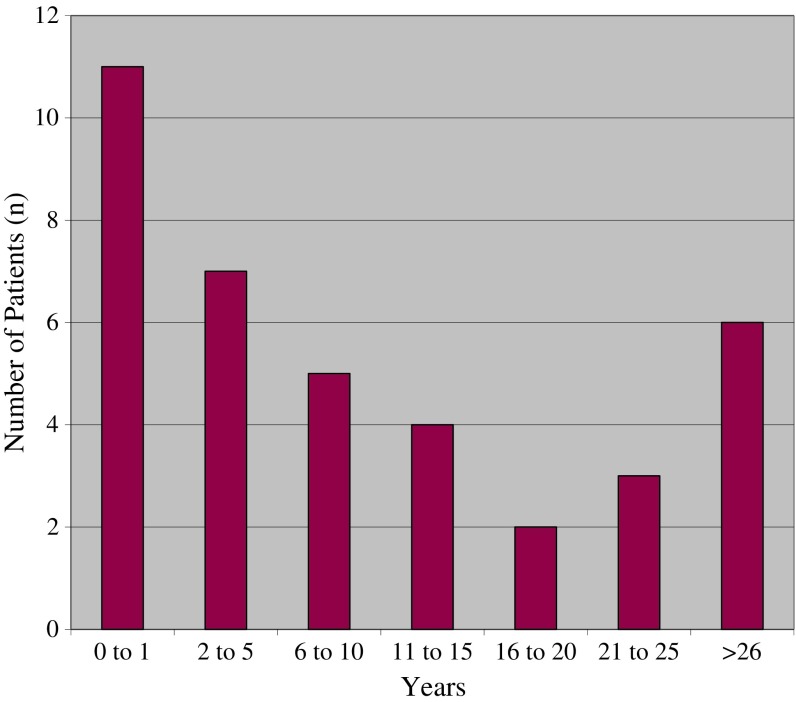

Typically, the onset of musculoskeletal symptoms preceded development of aortic insufficiency by many years; an average taken from reported cases was 13 years, with a range from 4 days to 61 years. (Fig. 1) There have been several case reports, however, of aortic insufficiency developing rapidly after the onset of ReA as soon as 4 days after diagnosis [5, 8, 10].

Fig. 1.

Time (in years) from onset of ReA to diagnosis of AI

Little has been published about the post-operative course of patients with ReA who require aortic valve replacement. Yates and Scott reported a case of a 36-year-old man with ReA who had successful aortic valve replacement and no residual symptoms at 4 years follow-up [12]. There is one reported case of progressive, severe calcification of a bovine aortic valve prosthesis in a patient with ReA at 7 years after his initial operation [30]. However, his case was complicated by severe coronary artery calcification both at the time of valve repair (requiring bypass grafting) and upon repeat presentation with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. It is unknown why the patient’s valve leaflets and coronary arteries became severely calcified, although it is postulated that his underlying inflammatory disease may have contributed. This patient suffered cardiogenic shock and expired.

The mechanism by which the aortic valve leaflets become targets in HLA-B27-associated diseases remains unclear. At one point, interest developed as to whether the HLA-B27 allele was independently associated with lone aortic insufficiency, in the absence of clinical spondylitis. Quayumi et al. examined 93 patients with lone aortic insufficiency and no spondyloarthritis and typed them for HLA-B27. In the subset of white males (n = 54), the HLA-B27 allele was present in five, which is not increased over the 5–14% baseline prevalence of this allele in this population [2]. Bergfeldt et al. similarly found that there was no increased prevalence of the HLA-B27 allele in patients with aortic insufficiency without any spondyloarthritis. However, when they examined 18 male patients with both aortic insufficiency and severe conduction system abnormalities (pacemaker-requiring bradycardia), they found the HLA-B27 allele present in 88%, with spondyloarthritis present in all of the HLA-B27-positive individuals. Seven of these 15 males had ankylosing spondylitis, four had sacroiliits, one had ReA, one had spondylitis without other criteria for ankylosing spondylitis, and two had previous episodes of arthritis/arthralgia with acute anterior uveitis (but did not carry the diagnosis of ReA). The expected prevalence of HLA-B27 in this population is 8% (p < 0.001), leading the authors to suggest a genetic syndrome of the heart consisting of aortic insufficiency and conduction system abnormalities, the “HLA-B27-associated cardiac syndrome” [31].

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of recognizing the association between HLA-B27-associated spondyloarthritis and serious aortic valvular complications. These complications can occur shortly after presentation; however, the risk of developing aortic insufficiency persists even decades out from diagnosis. Clinicians should maintain a high suspicion for aortic insufficiency in patients with ReA, including a low threshold for echocardiographic evaluation, as heightened awareness can lead to earlier identification and potentially avoidance of fatal events in these patients.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the reporting of this case, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Colmegna I, Cuchacovic R, Espinoza LR. HLA-B27-associated reactive arthritis: pathogenetic and clinical considerations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):348–369. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.348-369.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qaiyumi S, Hassan ZU, Toone E. Seronegative spondyloarthropathies in lone aortic insufficiency. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(5):822–824. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360050066010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodnan GP, Benedek TG, Shaver JA, Fennell RH., Jr Reiter’s syndrome and aortic insufficiency. JAMA. 1964;182:889–894. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070120011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulus HE, Pearson CM, Pitts W., Jr Aortic insufficiency in five patients with Reiter’s syndrome. A detailed clinical and pathologic study. Am J Med. 1972;53(4):464–472. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machado H, Befeler B, Morales AR, Vargas A, Aranda J. Aortic insufficiency in Reiter’s syndrome. South Med J. 1976;69(7):955–957. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197607000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosh JA, Barritt DW, Jayson MI. Cardiac lesions of Reiter’s syndrome and ankylosing spondylitis. Br Heart J. 1973;35(5):553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins P. Aortic incompetence and active myocarditis in Reiter’s disease. Br J Vener Dis. 1972;48(4):300–303. doi: 10.1136/sti.48.4.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good AE. Reiter’s disease: a review with special attention to cardiovascular and neurologic sequelae. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1974;3(3):253–286. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(74)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zvaifler NJ, Weintraub AM. Aortitis and aortic insufficiency in the chronic rheumatic disorders—a reappraisal. Arthritis Rheum. 1963;6:241–245. doi: 10.1002/art.1780060308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misukiewicz P, Carlson RW, Rowan L, Levitt N, Rudnick C, Desai T. Acute aortic insufficiency in a patient with presumed Reiter’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51(5):686. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.5.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergfeldt L. HLA-B27-associated cardiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8Pt1):621–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_Part_1-199710150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yates DB, Scott JT. Cardiac valvular disease in chronic inflammatory disorders of connective tissue: factors influencing survival after surgery. Ann Rheum Dis. 1975;34:321–325. doi: 10.1136/ard.34.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron JH. Heberden Society, clinical meeting. Ann Rheum Dis 26 Feb. 1960;19:183–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.19.2.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergfeldt L, Edhag O, Rajs J. HLA-B27-associated heart disease. Clinicopathologic study of three cases. Am J Med. 1984;77(5):961–967. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block SR. Reiter’s Syndrome and Acute Aortic Insufficiency. Arthritis Rheum. 1972;15(2):218–220. doi: 10.1002/art.1780150214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cliff JM. Spinal bony bridging and carditis in Reiter’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1971;30(2):171–179. doi: 10.1136/ard.30.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon AJ. “Rheumatoid arthritis” with negative serological reaction. Ann Rheum Dis. 1960;19:209–228. doi: 10.1136/ard.19.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du Bois RM, Freedman S. Rheumatoid factor in a patient with Reiter’s disease and aortic incompetence. Br Med J. 1977;41(6):451–455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6097.1260-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubscher O, Graci y Susini J. Aortic insufficiency in Reiter’s syndrome of juvenile onset. J Rheum. 1984;11(1):94–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huppertz HI, Sandhage K. Reactive arthritis due to Salmonella enteritidis complicated by carditis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(11):1230–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kean WF, Anastassiades TP, Ford PM. Aortic incompetence in HLA B27-positive juvenile arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1980;39(3):294–295. doi: 10.1136/ard.39.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podell TE, Wallace DJ, Fishbein MC, Bransford K, Klinenberg JR, Levine S. Severe giant cell valvulitis in a patient with Reiter’s syndrome. Arth Rheum. 1982;25(2):232–234. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruppert GB, Lindsay J, Barth WF. Cardiac conduction abnormalities in Reiter’s syndrome. Am J Med. 1982;73(3):335–340. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toone EC, Pierce EL, Hennigar GR. Aortitis and aortic regurgitation associated with rheumatoid spondylitis. Am J Med. 1959;26(2):255–263. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unverferth DV, Beman FM, Ryan JM, Whisler RL. Reiter’s aortitis with pericardial fluid, heart block and neurologic manifestations. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(2):232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vazquez de Corral L, Mejas E, Rivera JV. Reiter’s syndrome: skeletal and cardiac scans. Bol Assoc Med P R. 1981;73(5):241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Leitner ER, Kotter V, Schroder R. Kardiale spatmanifestationen des morbus Reiter. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1981;106(29–30):939–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yates DB, Scott JT. Cardiac valvular disease in chronic inflammatory disorders of connective tissue. Ann Rheum Disc. 1975;34(4):321–325. doi: 10.1136/ard.34.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csonka GW, Litchfield JW, Oates JK, Wilcox RR. Cardiac lesions in reiter’s disease. Brit Med J. 1961;28:243–247. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5221.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard JH, Litovsky SH, Tallaj JA, Liu X, Holman WL. Xenograft calcification in reiter’s syndrome. J Heart Valv Dis Mar. 2007;16(2):159–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergfeldt L, Insulander P, Lindbolm D, Moller E, Edhag O. HLA-B27: an important genetic risk factor for lone aortic regurgitation and severe conduction system abnormalities. Am J Med. 1988;85(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]