Non-technical summary

Appropriate regulation of ion channel expression is critical for the maintenance of both electrical stability and normal contractile function in the heart. A classic way to study the robustness of biological systems is to examine the effects of changes in gene dosage. We have studied how the heart responds to changes in the L-type calcium channel gene dosage. Homozygous Cav1.2 knockout in the adult heart is lethal, without compensatory responses in expression of other calcium channel genes. Following heterozygous knockout, Cav1.2 mRNA levels are not buffered, Cav1.2 membrane protein levels are partly buffered and L-type calcium current expression is relatively well buffered. These data are consistent with a passive model of Cav1.2 biosynthesis that includes saturated steps, which act to buffer Cav1.2 protein and L-type calcium current expression. The results suggest that there is little or no homeostatic regulation of calcium current expression in either heterozygous or homozygous knockout mice.

Abstract

Abstract

Mechanisms that contribute to maintaining expression of functional ion channels at relatively constant levels following perturbations of channel biosynthesis are likely to contribute significantly to the stability of electrophysiological systems in some pathological conditions. In order to examine the robustness of L-type calcium current expression, the response to changes in Ca2+ channel Cav1.2 gene dosage was studied in adult mice. Using a cardiac-specific inducible Cre recombinase system, Cav1.2 mRNA was reduced to 11 ± 1% of control values in homozygous floxed mice and the mice died rapidly (11.9 ± 3 days) after induction of gene deletion. In these homozygous knockout mice, echocardiographic analysis showed that myocardial contractility was reduced to 14 ± 1% of control values shortly before death. For these mice, no effective compensatory changes in ion channel gene expression were triggered following deletion of both Cav1.2 alleles, despite the dramatic decay in cardiac function. In contrast to the homozygote knockout mice, following knockout of only one Cav1.2 allele, cardiac function remained unchanged, as did survival. Cav1.2 mRNA expression in the left ventricle of heterozygous knockout mice was reduced to 58 ± 3% of control values and there was a 21 ± 2% reduction in Cav1.2 protein expression. There was no significant reduction in L-type Ca2+ current density in these mice. The results are consistent with a model of L-type calcium channel biosynthesis in which there are one or more saturated steps, which act to buffer changes in both total Cav1.2 protein and L-type current expression.

Introduction

The robustness of biological systems reflects the ability of the system to maintain normal function following a significant perturbation (Wagner, 2007). For the cardiac electrophysiological system, robustness corresponds to the ability to maintain stable electrical function and excitation–contraction coupling following pathological, pharmacological or genetic insults to the system. Two broad classes of mechanisms can potentially contribute to the robustness of biological systems.

One possibility is that feedback loops could monitor and maintain system states and actively respond to perturbation, as envisioned by classical control theory (Sauro, 2009). In principle, homeostatic feedback loops could act to maintain a specific state in electrophysiological systems, such as a particular action potential morphology or firing pattern, by regulating basal ion channel expression levels in a coordinated fashion. Such a mechanism requires very accurate monitoring of the state of the system in order to provide useful regulatory feedback (Liu et al. 1998). For the regulation of electrophysiological function and the expression of voltage-gated ion channels, only a limited amount of feedback information about the system state is available, primarily in the form of calcium fluxes, and this information may be inadequate to regulate the relatively large number of different components in the system (Rosati & McKinnon, 2004).

Alternatively, the networks that underlie a particular biological function could have evolved to be relatively stable in response to at least some perturbations and thereby maintain function without the requirement to accurately monitor the overall system state. In principle, the biosynthetic networks that underlie the expression of functional channels in the cell membrane could function in this way (Rosati & McKinnon, 2004). Robust biosynthetic networks could act to maintain electrical stability by buffering channel expression levels during a variety of disturbances affecting mRNA or protein expression levels, without directly monitoring electrophysiological function.

Surprisingly, this second form of robustness appears to be relatively rare. Heterozygous null mutations of the SCN5A, KCNQ1, KCNH2 and KCNJ2 genes in humans all produce haploinsufficiencies due to destabilization of cardiac electrical function (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Chen et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1999; Fodstad et al. 2004). Similarly, heterozygous knockouts of the Scn5a and Kcnip2 genes in mice produce an approximately 50% reduction in the expression of the INa and Ito currents, respectively, in cardiac myocytes (Kuo et al. 2001; Papadatos et al. 2002). Null mutations in one allele of multiple different ion channel genes expressed in mouse brain also result in significant reductions in basal channel expression or related impairments of electrophysiological function (Planells-Cases et al. 2000; Ahern et al. 2001; Osanai et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2006; Brew et al. 2007; Tzingounis & Nicoll, 2008). Although most ion channels have relatively complex biosynthesis pathways (Deutsch, 2003; Delisle et al. 2004), it appears that for many physiologically important channels there is little or no buffering of basal channel expression levels following the loss of one allele.

We have previously argued that heterozygous knockouts of ion channel genes are a good system in which to study the robustness of basal ion channel expression in vivo (Rosati & McKinnon, 2004). A valid criticism of conventional knockout technology is that mutations that are present throughout the course of development can modify normal development and ion channel expression, thereby confusing interpretation of the results seen in the adult. For this reason, we have used an inducible knockout system in the current study.

We have chosen to study the Cav1.2 gene, which encodes the channel that carries the vast majority of the L-type calcium current in the adult heart (Bodi et al. 2005; Rosati et al. 2007), because prior studies suggest that expression of Cav1.2 is relatively robust in many pathophysiological conditions affecting ventricular function, at least in comparison to most other ion channels (Beuckelmann et al. 1991; Schroder et al. 1998; Tomaselli & Marban, 1999; He et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2002; Piacentino et al. 2003; Pitt et al. 2006).

Methods

All animal procedures have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Stony Brook University.

Homozygote and heterozygote inducible knockout mice

Mice bearing two loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the Cav1.2 gene (Cacna1c) (‘floxed’ allele) have been described previously (White et al. 2008). These mice were bred with transgenic mice carrying a transgene comprising an alpha-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter driving a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (Mer-Cre-Mer), which targets expression of this recombinase to the heart (Sohal et al. 2001). To simplify the production of mice for experimental analysis, mice homozygote for both the floxed Cav1.2 gene and the transgene (Cav1.2f /f and Cre+/+) were bred. Homozygosity was confirmed by breeding the homozygous mice with wild-type animals and then verifying heterozygosity of the pups. Through selective breeding of these animals, mice that carried the Cre transgene and were either homozygous or heterozygous for the floxed Cav1.2 allele were obtained for the experiments.

There was no leakage of Cre activity and Cav1.2 gene recombination was undetectable in heart tissue prior to tamoxifen treatment (Supplemental Material, Fig. 1A). Recombination following tamoxifen treatment was cardiac tissue specific, and was not observed in non-cardiac tissues (Supplemental Material, Fig. 1B).

In the standard experimental protocol, Cav1.2 gene knockout was induced in 6- to 7-week-old mice of either sex by i.p. injection of approximately 33 mg kg−1 day−1 tamoxifen (Sigma T5648) in peanut oil (Sigma P2144) per day, for five consecutive days. After the end of the injection period the mice were left for 3–5 weeks to allow for decay of mRNA and protein products from the targeted gene before subsequent analysis. This time interval was judged to be adequate based on the survival time of the homozygous mice (11.9 ± 3 days) and direct measurements of Cav1.2 mRNA and protein half-lives (Fig. 6). This waiting period also allowed for wash-out of any acute effects of the tamoxifen treatment, if present.

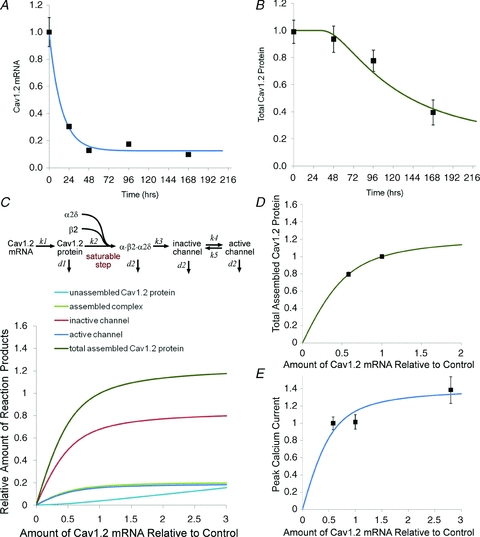

Figure 6. Decay of Cav1.2 mRNA and protein following homozygous Cav1.2 knockout and a model of Cav1.2 channel biosynthesis.

A, decay of Cav1.2 mRNA in homozygous knockout mice following a single tamoxifen injection (see Methods). Data points show mean ± SEM (n = 3–7). Data were fitted with a single exponential: τ = 14.7 h, baseline = 0.12. B, decay of Cav1.2 protein in the same mice shown in A. Curve was fitted using the kinetic model shown in panel C. C, kinetic model of Cav1.2 channel biosynthesis. The amount of the four forms of the Cav1.2 protein plus total assembled Cav1.2 protein is plotted as a function of the amount of Cav1.2 mRNA. Total assembled Cav1.2 protein corresponds to the Western blot measurements shown in Fig. 4C and the corresponding fit is shown in panel D. Active protein corresponds to the number of functional channels corresponding to peak calcium current shown in Fig. 3A and the corresponding fit is shown in panel E. Data for peak current following overexpression of Cav1.2 mRNA also shown in panel E are taken from Muth et al. (1999). Note that total protein and peak current have different dependencies on the amount of Cav1.2 mRNA. The small decline in peak calcium current predicted by the model for the heterozygous knockout mice would not be readily detected experimentally. Values are expressed relative to control levels and in some cases the symbols obscure the error bars. Fit parameters were: k1 = 0.029 h−1, k4 = 0.032 h−1, K (the saturation constant) = 0.0092. The decay rate for the assembled protein was taken from the fit to the protein decay data shown in panel B, d2 = 0.012 h−1. The other parameters were constrained by these values (see Methods).

For the study of Cav1.2 mRNA and protein decay times, the standard tamoxifen treatment protocol was modified in two ways in order to better synchronize gene knockout. The mice were placed on a soy-free diet for 1 week before receiving a single injection of tamoxifen (50 mg kg−1 day−1). These two changes were taken in order to minimize the overlap between the tamoxifen treatment period and the decay of Cav1.2 protein. The soy-free diet may improve the effectiveness of the tamoxifen treatment, since it does not contain phyto-oestrogens, which means that the Cav1.2 protein decay time may not be directly comparable to the survival times observed using the standard protocol.

It has been suggested that induction of Cre recombinase expression can induce transient cardiomyopathy (Koitabashi et al. 2009). We obtained more efficient gene ablation than described in this report, using a lower tamoxifen dose. Under our experimental conditions, no changes in calcium channel or auxiliary subunit gene expression were observed in tamoxifen treated Cre-positive mice, nor were there significant changes in the expression of the calcium handling genes SERCA2A, phospholamban or NCX1 in the experimental mice (not shown). Notably, even in the tamoxifen-treated heterozygous knockout mice there was no change in cardiac contractile function.

Genotyping

To assess the outcome of breedings, mouse genomic DNA was extracted from tail biopsies using phenol extraction. To confirm genotypes in animals killed for biochemical or electrophysiological experiments, genomic DNA was prepared from liver tissue using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

Genotyping was performed using real-time PCR. This allowed us to reliably rule out false positive results due to contamination of the PCR assay. The complete genotyping procedure consisted of separate assays to identify the knock-in (‘floxed’) allele, the wild-type allele and knock-out allele following recombination. The following primer pairs were used:

Cre recombinase:

CATTTGGGCCAGCTAAACAT and TAAGCAATCCCCAGAAATGC;

Cav1.2 knock-in allele:

GGGGGAACTTCCTGACTAGG and ATCTTTGGTTCAGGGATGCTT;

Cav1.2 wild-type and knock-out alleles:

GTTCCTGCAATAGCTTGAGGG and CATGGAGTCTGGGGGGAGGTC.

Primers directed against the Kv1.2 gene were used as an internal control for normalization between samples (TGGCTTCTCTTTGAATACCCAGA and TTGCTGGGACAGGCAAAGAA). A positive and a negative control sample were included in each experiment.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in anaesthetized animals (1–2% isoflurane) using a Vevo 770 ultrasound device (VisualSonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) with a 30 MHz transducer. The Vevo measurement and calculations software package was used to generate left ventricular measurements and calculations derived from the tracings of the collected echocardiographic data. The following parameters were obtained using M-mode transthoracic views: left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), ejection fraction (EF). Contractile function was calculated as fractional shortening = (LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD × 100%.

Analysis of calcium channel subunit mRNA expression

Analysis of mRNA expression was performed using real-time PCR as described previously (Rosati et al. 2007, 2008). For RNA isolation, mice were killed with isoflurane and the hearts were quickly removed. The left ventricular free wall and septum were dissected and frozen in liquid N2. Total RNA was prepared using Qiagen RNeasy columns with DNase treatment. RNA samples were quantified, re-diluted to give nominally equal concentrations and quantified a second time using spectrophotometric analysis. Human RNA samples were obtained from independent commercial suppliers (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA and BioChain Institute Inc., Hayward, CA, USA).

cDNAs were prepared from a starting RNA amount of 5 μg per sample. In vitro reverse transcription was performed as described previously (Rosati et al. 2004). Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green QuantiTect PCR Kit (Qiagen) with a 7300 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Experimental samples were analysed in triplicate. Threshold crossing points were converted to expression values automatically (Larionov et al. 2005). Real-time PCR products were analysed by gel electrophoresis and sequenced to confirm specificity of the amplification. Gene expression across RNA samples was normalized using 18S and 28S rRNAs as internal controls.

Multiple primer pairs were used to analyse expression of every gene tested in order to detect primer dependent artifacts. The results from each primer pair were averaged. For quantification of the Cav1.2 gene, the following primer pairs were used:

ATGCCAACATGAATGCCAAT and CCATTCAACAATGCTTATGCAC;

CAGCTCATGCCAACATGAAT and TGCTTCTTGGGTTTCCCATA;

CTACTCCAGGGGCAGCACT and TTTCCATTCAACAATGCTTATG.

Detection and quantitation of Cav1.2 protein by western blot

Protein samples were prepared from tissue samples that were frozen in liquid N2 and then homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), containing several protease inhibitors (Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablets, Roche). The homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at 1000 g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 48,000 g at 4°C for 45 min. The pellet containing membrane proteins was resuspended in lysis buffer and rehomogenized and sonicated to get complete resuspension. Protein samples were quantified, re-diluted to give nominally equal concentrations and quantitated a second time colorimetrically (BCA, Pierce).

Samples, 2.5 μg of membrane proteins in lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Novex, Invitrogen) with 10% dithiothreitol (DTT), were heated at 70°C for 10 min, prior to loading on a pre-cast 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPage, Invitrogen). Electrophoretic separation of the proteins was carried out in SDS-Mops running buffer. Proteins were then blotted onto PVDF membranes. After a blocking step, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking solution with the primary antibodies (anti-Cav1.2, 1:200, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel, cat. no. ACC-003 and anti-actin (internal control), 1:1,000, Chemicon, cat. no. MAB1501). Incubation in alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Tropix, Applied Biosystems, 1:10,000, anti-rabbit for the Cav1.2 or anti-mouse for actin) was performed at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were exposed to chemiluminescent substrate (CSPD, Tropix, Applied Biosystems) and luminescence was quantified using a Kodak Image Station 440CF.

Mouse ventricular myocyte isolation

Cardiac myocytes were isolated from the ventricles of 9- to 11-week-old mice using a method described previously (Rosati et al. 2008). Mice were killed by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg kg−1 of sodium pentobarbital. The heart was quickly removed and rinsed in three changes of cold basic solution (BS) (112 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 1.7 mm NaH2PO4, 1.6 mm MgCl2, 4.2 mm NaHCO3, 20 mm Hepes, 5.4 mm glucose, 4.1 mm l-glutamine, 10 mm taurine, minimal essential medium vitamins and amino acids, pH 7.4) containing 20 units ml−1 of heparin. The aorta was cannulated using a 22-gauge blunt needle and the heart was rinsed with oxygenated BS containing 1 mg ml−1 2,3-butanedione monoxime at 37°C on a Langendorff apparatus for 10 min. Digestion of the myocardium was performed using 36 μg ml−1 Liberase Blendzyme 4 (Roche) in oxygenated BS for 5–7 min. After digestion, the heart was rinsed in Kraft-Brühe (KB) solution (74.6 mm KCl, 30 mm K2HPO4, 5 mm MgSO4, 5 mm pyruvic acid, 5 mmβ-hydroxybutyric acid, 5 mm creatine, 20 mm taurine, 10 mm glucose, 0.5 mm EGTA, 5 mm Hepes and 5 mm Na2-ATP, pH 7.2). The atria were subsequently trimmed off and the ventricles were minced in KB solution. The tissue was collected in a 15 ml conical tube and further dissociated by gentle trituration. The cell suspension was filtered through a 210 μm nylon mesh and allowed to sediment. The pellet was washed once in KB solution before the cells were used.

Recording of calcium currents

Only rod-shaped calcium-tolerant myocytes were used for electrophysiological recordings, which were performed at room temperature (23°C). Gigaseals were obtained using 1.5–3 MΩ borosilicate glass pipettes and whole-cell L-type Ca2+ currents (ICa,L) were measured in voltage-clamp mode using an Axopatch 200A amplifier with a Digidata 1322A digitizer and the pCLAMP 8 software package (all from Axon Instruments). The experimental recording conditions for ICa,L have been previously described (Rosati et al. 2008). Briefly, the internal solution contained (mm): caesium aspartate 115, CsCl 20, EGTA 11, Hepes 10, MgCl2 2.5 and Mg-ATP 2 (pH 7.2). The Na+- and K+-free bath solution contained (mm): TEA-Cl 137, CsCl 5.4, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, Hepes 5, glucose 10 and 4-aminopyridine 3 (pH 7.4). For ICa,L peak determination, the current was activated from a holding potential of −50 mV by 10 mV steps, ranging from −50 to +60 mV. The maximum absolute value of the current obtained (in pA) was divided by the cell capacitance (in pF).

Kinetic model and data fitting

The kinetic model was coded using Python and the data values were fitted using a simplex search algorithm from a standard Python library. Four free parameters were used for data fitting: k1, k4, K (the saturation constant) and a constant, which scaled the number of active channels to the peak current density but otherwise had no effect on the function of the model. The decay rate for the assembled channel protein was measured by fitting the model to the protein decay data (Fig. 6B), d2 = 0.012 h−1 with a delay time of 30 h. The other rate constants in the model were constrained as follows: k2 = k1/2, k3 = 2·k1, k5 = 4·k4, d1 = 40·d2. These constraints were chosen to produce a predominance of inactive channels in the cell membrane, as suggested from charge movement measurement experiments (Bean & Rios, 1989; Hadley & Lederer, 1991). A high rate of degradation of unassembled subunits has been demonstrated in some channel biosynthesis systems (Merlie & Smith, 1986). It was assumed that the channel assembly step (k2) was saturable, with Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Without this assumption Cav1.2 protein and current levels would scale linearly and infinitely with the amount of Cav1.2 mRNA, which is unrealistic. The transport to the cell membrane step may also be saturable, but adding this feature to the model had relatively little effect and was omitted for simplicity.

Results

Validation of the inducible knockout system using homozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice

Homozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice (also transgenic for a cardiac-specific tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase) were used to confirm that both the genetic modification and the tamoxifen treatment worked as expected. Homozygous mice were treated for 5 days by i.p. injection of tamoxifen in peanut oil (33 mg kg−1 day−1). As expected for a complete deletion of the Cav1.2 gene, all the tamoxifen-treated mice died following treatment. Homozygous animals had an average survival time of 11.9 ± 3 days (mean ± SD, n = 14) following initiation of the 5 day injection period (Fig. 1A). No mice injected with peanut oil alone (the drug vehicle) died during the same time period, and these mice had long-term viability (tested up to 2 months).

Figure 1. Effect of homozygous Cav1.2 knockout on survival and cardiac function.

A, Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival plot of homozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice also expressing a tamoxifen-inducible, cardiac-specific Cre recombinase. Mice were treated for 5 days by i.p. injection of tamoxifen (33 mg kg−1 day−1). Average survival time was 11.9 ± 3 days (mean ± SD, n = 14), counting from the start of the 5 day injection period (day 0). No control mice died during the same time period. B, echocardiographic analysis of control and homozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice following tamoxifen injection. C and D, bar graphs show average data for fractional shortening (C) and end-diastolic volume (D) for control and tamoxifen treated homozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice. Data are from tamoxifen treated mice within 2 days of death and control mice following peanut oil (drug vehicle) injection tested during the same time period. Error bars are SEM, and n = 8 and 6, respectively. In both cases values for treated animals were significantly (P < 0.001) different from control values.

Mice examined within 2 days of death using echocardiography displayed a profound decrease in myocardial contractility, as assessed by fractional shortening, consistent with a large reduction in calcium current expression (Fig. 1B and C). There was also a significant increase in ventricular end diastolic volume (Fig. 1D).

To analyse mRNA and protein expression in the homozygous mice, the physiological status of tamoxifen-treated mice was followed longitudinally using echocardiography and mice were killed and tested for mRNA and protein expression when fractional shortening fell below 5%.

In the tamoxifen-treated homozygous mice, Cav1.2 mRNA expression was reduced to 11 ± 1% relative to controls (Fig. 2A). Assuming that Cav1.2 mRNA expression is restricted solely to myocytes expressing the α-MHC gene, then, based on the mRNA results, the efficiency of gene deletion is approximately 89% under our experimental conditions. If non-trivial amounts of Cav1.2 mRNA are expressed in non-myocytes in the ventricle wall, then the efficiency would be somewhat higher.

Figure 2. Effect of homozygous Cav1.2 knockout on calcium channel mRNA and protein expression.

A, analysis of Cav1.2 mRNA expression in the left ventricles of homozygous Cav1.2 KO mice. Cav1.2 mRNA abundance was reduced to 11 ± 1% of control values in homozygous tamoxifen treated mice (P < 0.0001, n = 7). B, Cav1.3 mRNA expression in the left ventricles of homozygous Cav1.2 KO mice was increased 59% compared to controls (P < 0.01, n = 18). C, comparison of the relative levels of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 mRNA expression in control and homozygous KO mice. D, standard curve for Cav1.2 detection by Western blot analysis; 0–3 μg of membrane protein was used in assay. Data points are means ± SEM (n = 6). Error bars are hidden by the symbols. E, Western blot analysis of Cav1.2 protein expression in the left ventricles of control and tamoxifen-treated homozygous Cav1.2 KO mice. The upper band corresponds to Cav1.2 protein and the lower band to actin, which served as an internal control for equal lane loading. F, bar graph showing average data for homozygous KO mice. Cav1.2 protein abundance was reduced to 19 ± 9% of control values in homozygous mice (n = 10 and 6 for control and treated animals, respectively).

There was a very limited compensatory increase in Cav1.3 mRNA expression in the adult homozygous Cav1.2 knockouts (Fig. 2B), much smaller than has been described in embryonic hearts using conventional Cav1.2 knockouts (Xu et al. 2003). Notably, Cav1.3 mRNA expression remained more than an order of magnitude smaller than would be required to compensate for the loss of Cav1.2 mRNA expression (Fig. 2C). Expression of other members of the Cav1 gene family, as well as Cav3 family genes, also remained at similarly low, or lower, levels relative to Cav1.2 gene expression in control hearts (not shown).

Cav1.2 protein expression in homozygous mice was analysed by Western blotting. Because linearity can be a problem with these assays, we tested a range of conditions in order to optimize the assay. The assay for Cav1.2 protein detection was found to be linear over the range 0–3 μg of membrane protein per sample (Fig. 2D). For all subsequent experiments, 2.5 μg of membrane protein was used in each independent sample.

There was a dramatic reduction in Cav1.2 protein expression in the homozygous animals (Fig. 2E and F). Cav1.2 protein was expressed at low but detectable levels in the hearts of homozygous knockout animals with severely compromised cardiac function. The average level of expression was 19 ± 9% of control values (mean ± SEM, n = 10 and 6 for control and treated animals, respectively). This result confirms the specificity of the Cav1.2 antibody used in the Western blot assay. A complete loss of Cav1.2 protein would not be expected because there is a residual level of Cav1.2 mRNA and the mice were presumably killed before the protein had declined to steady-state levels, which are clearly not consistent with survival.

Analysis of heterozygous floxed mice following induction of Cav1.2 gene deletion

The effect of tamoxifen treatment appears to reach completion within 2 weeks from the beginning of tamoxifen injections (Fig. 1A). As a consequence, all physiological and biochemical experiments on heterozygous mice were performed 3–5 weeks after initiation of tamoxifen injections. In contrast to the results for the homozygous mice, no heterozygous mice died during this 3–5 week period following tamoxifen injection. No fatalities were observed in a subset of treated heterozygous mice that were examined over a longer 2 month period.

Again, in contrast to the results for the homozygous mice, echocardiographic analysis of cardiac function in the heterozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice revealed no differences in the functional properties of the hearts between control and treated animals. Fractional shortening was unchanged (25.3 ± 1%versus 25.1 ± 1% for control and treated animals, respectively, means ± SEM, n = 11 and 12), nor was end-diastolic volume significantly changed (65 ± 2.5 μl versus 65 ± 2.8 μl, mean ± SEM, n = 11 and 12, respectively).

Calcium current expression in heterozygous Cav1.2 KO mice

There was no significant difference in peak current density in myocytes obtained from control and tamoxifen-treated heterozygous floxed mice (Fig. 3A). There was no significant difference in cell capacitance between the two groups (146 ± 51 vs. 127 ± 38 pF for control and tamoxifen treated, respectively, means ± SD, n = 27 and 21).

Figure 3. Effect of heterozygous Cav1.2 knockout on L-type calcium current expression and function.

A, bar graph comparing peak calcium current expression in ventricular myocytes obtained from heterozygous floxed Cav1.2 mice treated with peanut oil alone (control) or with tamoxifen (7.2 ± 1 and 7.3 ± 1 pA pF−1, n = 27 and 21 respectively, mean ± SEM). Error bars are SEM. B, recordings of calcium currents from myocytes obtained from control and tamoxifen-treated mice. Holding potential was −50 mV, and currents were elicited by voltage steps over the range −30 to +10 mV. C, normalized I–V curves for ICa,L in ventricular myocytes from control and tamoxifen-treated mice. D, inactivation time constants for ICa,L. The data were fitted with a biexponential curve with two time constants (τf and τs). E, steady-state inactivation for ICa,L. Data were fitted with Boltzmann curves (V1/2 = −21.6 ± 1.3 and −21.4 ± 0.4; k = 6.2 ± 0.5 and 5.6 ± 0.2; n = 11). Data points are means ± SEM, and symbols are control (blue triangles) and tamoxifen-treated (red squares). Recordings were made on myocytes obtained from mice 3–5 weeks after the initiation of tamoxifen injections.

The biophysical properties of the currents in the tamoxifen-treated animals were also unchanged (Fig. 3B). The I–V relationships for currents obtained from the two sets of mice are virtually identical (Fig. 3C). The rate of inactivation and steady-state inactivation curves are similarly unchanged (Fig. 3D and E).

Reduced Cav1.2 mRNA and protein expression in heterozygous Cav1.2 KO mice

Cav1.2 mRNA expression in the left ventricle of heterozygous floxed mice treated with tamoxifen or with peanut oil alone was compared using real-time PCR. In tamoxifen-treated heterozygous mice Cav1.2 mRNA expression was reduced to 58% relative to controls (Fig. 4A). This value was not significantly different from the value of 55.5% interpolated from the homozygote mouse data, assuming a similar efficiency for recombination and negligible non-myocyte Cav1.2 mRNA expression. This suggests that there is no significant compensation of mRNA expression from the remaining intact Cav1.2 allele in the heterozygous knockout mice.

Figure 4. Effect of heterozygous Cav1.2 knockout on calcium channel mRNA and protein expression.

A, analysis of Cav1.2 mRNA expression in the left ventricles of heterozygous Cav1.2 KO mice was determined using real-time PCR. Cav1.2 mRNA abundance was reduced to 58 ± 3% of control values in heterozygous mice (P < 0.0001, n = 13 and 10, respectively). Error bars are SEM. B, Western blot analysis of Cav1.2 protein expression in cell membranes from the left ventricles of control and tamoxifen-treated heterozygous Cav1.2 KO mice. Upper band corresponds to Cav1.2 protein and lower band to actin, which served as an internal control. C and D, bar graphs showing average data for Cav1.2 (C) and actin (D) expression. Cav1.2 protein abundance was reduced to 79 ± 2% of control values in heterozygous mice (P < 0.0001) whereas actin expression was unchanged (n = 19 and 18 for control and treated animals, respectively).

There was a modest but significant (P < 0.001) reduction in Cav1.2 protein expression in tamoxifen-treated heterozygous mice relative to control animals. Cav1.2 expression in tamoxifen-treated animals was 79 ± 2% of controls (mean ± SEM, n = 19 and 18 for control and treated animals). There was no change in actin expression in these same tissue samples. Expression of actin, which acted as the internal control, was 101 ± 2% of control values (mean ± SEM, n = 19 and 18 for control and treated animals).

No change in Cav1.2 related gene expression in heterozygous knockout mice

The expression of genes whose upregulation could potentially explain the unchanged levels of ICa,L found in heterozygous Cav1.2 knockout mice was examined. In particular, no change in Cav1.3 mRNA expression was found following heterozygous Cav1.2 gene knockout. Cav1.1 and Cav1.4 mRNAs were expressed at very low or undetectable levels. Similarly, no change in Cavβ2, Cavα2δ-1 and Cavα2δ-2 mRNA was observed (data not shown). These mRNAs encode auxiliary subunits that have been shown to cause an increase in Cav1.2 current or to be associated with the α subunit in cardiac myocytes (Bodi et al. 2005).

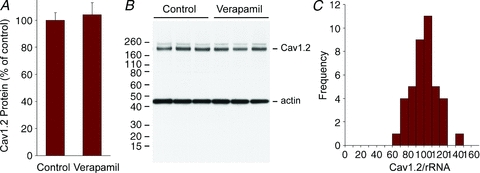

Effects of blockade of the calcium current on Cav1.2 mRNA and protein expression

It has been proposed that calcium fluxes can actively regulate calcium channel expression, based on results using verapamil treatment in vivo (Schroder et al. 2007). To test this possibility the effects of verapamil treatment on Cav1.2 protein expression were examined. In initial experiments, even relatively high doses of verapamil (up to 25 mg kg−1 day−1 for 4 days) had no effect on Cav1.2 protein expression. The highest dosage of verapamil that could be tolerated without significant lethality was 75 mg kg−1 day−1 split into two daily doses. Even at this highest dosage (75 mg kg−1 day−1 for 3.5 days) there was no change in Cav1.2 protein expression relative to control animals (Fig. 5A and B). No change in Cav1.2 mRNA expression was observed in the same animals.

Figure 5. Effect of verapamil on Cav1.2 protein expression and variation of Cav1.2 mRNA in mice.

A, analysis of Cav1.2 protein following verapamil treatment (75 mg kg−1 day−1 for 3.5 days). Bar graph shows average data for Cav1.2 expression (100 ± 5 and 104 ± 9, n = 6 and 10 respectively, mean ± SEM). Cav1.2 protein abundance was unchanged in verapamil-treated mice compared to control mice injected with the same volume of the vehicle (water). B, Western blot analysis of Cav1.2 protein expression in cell membranes from left ventricles of control and verapamil-treated mice. Upper band corresponds to Cav1.2 protein and lower band to actin, which served as an internal control. The higher molecular weight band above the Cav1.2 band is a non-specific signal detected intermittently by the anti-Cav1.2 antibody. C, bar graph showing expression of Cav1.2 mRNA in 40 control mouse ventricles from 8- to 10-week-old mice of either sex. The difference between the lowest and highest expressing animal was 2.4-fold with a normalized mean and standard deviation of 100 ± 17. Data are normalized to ribosomal RNA and expressed as a percentage of the mean.

Variation in Cav1.2 mRNA expression

The effective buffering of experimentally induced changes in Cav1.2 mRNA expression raised the possibility that control of Cav1.2 gene expression could be relaxed, resulting in a broad distribution of Cav1.2 mRNA. Consistent with this possibility, one study of Cav1.2 mRNA expression in tissue samples from human ventricle has reported an unusually high degree of variability, with a normalized mean and standard deviation of 100 ± 51 (Wang et al. 2006). A second study, also using human ventricle, found a much tighter distribution, 100 ± 30 (mean ± SD) (Gaborit et al. 2007).

In mouse ventricle we did not observe unusual variation in Cav1.2 expression (100 ± 17, mean ± SD, n = 40) (Fig. 5C). Variation in human heart RNA samples was higher (100 ± 31, mean ± SD, n = 8), similar to that described by Gaborit et al. (2007). The tighter distribution in mouse probably reflects the use of inbred animals and the more consistent age and condition of the tissue samples. Given the variable sources for the human mRNA, the results are not consistent with a very broad distribution of Cav1.2 mRNA expression levels, as described by Wang et al. (2006).

Model of Cav1.2 biosynthesis

To begin to understand the biosynthesis of the Cav1.2 channel, the decay of the Cav1.2 mRNA and protein was examined following gene knockout in homozygous mice (Fig. 6A and B). Induction of knockout in these experiments used a single tamoxifen injection at time zero (see Methods). The decay of Cav1.2 mRNA was quite rapid, with a time constant of 14.7 h. The steady-state baseline value was 12%, similar to that observed using our standard knockout protocol (Fig. 2A). The decay of Cav1.2 protein was more complex, beginning after a noticeable delay. This delay suggests that only the later steps in the biosynthesis of the Cav1.2 subunit are effectively seen by the Western blot assay. The early intermediates are relatively rare, have short half-lives or are not efficiently captured by the membrane protein preparation procedure.

The results from the heterozygous knockout mice show that, relative to the reduction in Cav1.2 mRNA, calcium current density is buffered more effectively than total Cav1.2 protein (Figs 3A and 4C). A simple model of channel biosynthesis (Fig. 6C) can account for these results, assuming that there is at least one saturating step in the biosynthetic pathway (see Methods). This model, when fitted to the current and protein data simultaneously, produces a good fit of the experimental data (Fig. 6B, D and E). The model predicts that there should be a small reduction in calcium current in the heterozygous knockouts that is within experimental error.

The key feature of this model is that at least one step in the biosynthetic pathway is saturated under wild-type conditions (Fig. 6C). Without the assumption of at least one saturable step, Cav1.2 protein and current levels would scale linearly and infinitely with the amount of Cav1.2 mRNA. The complex dependency of calcium channel expression on multiple subunits (Bodi et al. 2005; Kobayashi et al. 2007) suggests that the assembly step is likely to be limiting, as assumed in the model. It is notable that calcium current expression is also buffered following reduction of Cavβ2 subunit expression in adult mice (Meissner et al. 2009), which is consistent with the assembly step also being saturated for Cavβ2. The large mismatch between calcium channel gating charge and the number of functional channels in the cell membrane (Bean & Rios, 1989; Hadley & Lederer, 1991) and the resultant relatively high level of channel expression in the cell membrane suggests that transport to the cell membrane may also be saturated.

Discussion

The effects of conditional knockout of the Cav1.2 gene in mouse heart were studied. The homozygous Cav1.2 knockout is lethal, without evidence for any effective compensatory responses in the adult heart. In contrast, following heterozygous knockout of the Cav1.2 gene in the adult heart, expression of the L-type calcium current is maintained at close to control levels. In marked contrast to previous studies on the heterozygous knockout of cardiac channel genes (Kuo et al. 2001; Papadatos et al. 2002), L-type calcium current expression is effectively buffered following deletion of one allele of the Cav1.2 gene. There are two alternative mechanisms that could account for this result.

One possibility is that the maintenance of stable calcium current expression following gene knockout is an intrinsic property of the channel biosynthetic network. Such a mechanism does not necessarily require either monitoring of electrophysiological function nor any form of feedback loop in order to buffer channel expression. Even a simple model of the calcium channel biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 6) can account for the data. Although this model undoubtedly lacks some features of the actual pathway, it is reasonable to consider this kind of mechanism to be the null hypothesis before evaluating other, more complicated alternatives.

The alternative hypothesis is that L-type calcium current expression levels are monitored and expression levels are actively maintained by a feedback loop. Three potential feedback mechanisms could regulate calcium channel expression.

First, changes in cardiac function could result in feedback via the sympathetic nervous system modifying the function of existing channels, as has been proposed to occur during heart failure (Schroder et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2002). Significant changes in the biophysical properties of ICa,L have been reported under these conditions (Chen et al. 2002). No change in the biophysical properties of the calcium current was observed in the present study (Fig. 3), suggesting that sympathetic feedback is unlikely to be a major compensatory mechanism.

A second possibility is that the calcium channel C-terminal tail, which can act as a transcription factor, might form part of a feedback loop to regulate expression of the channel at the level of transcription (Gomez-Ospina et al. 2006; Schroder et al. 2009). In the current study, buffering of calcium current expression following loss of one Cav1.2 allele is almost entirely post-transcriptional. There is no significant increase in transcription from the remaining Cav1.2 allele or from auxiliary subunit genes, suggesting that changes in gene regulation are of limited importance.

A third possibility is that calcium flux through the channel might provide a feedback signal that can be monitored to regulate Cav1.2 channel expression. Based on evidence obtained using the calcium channel blocker verapamil, it has been suggested that reduced calcium influx can trigger an increase in Cav1.2 channel expression (Schroder et al. 2007). We did not observe any effect of verapamil on Cav1.2 mRNA or protein expression in vivo. Our results are in agreement with multiple prior studies showing that there is no change in calcium channel protein expression following in vivo verapamil treatment, as assessed by dihydropyridine binding analysis (McCaughran & Juno, 1988; Lonsberry et al. 1992, 1994; Chapados et al. 1992).

Moreover, the use of calcium fluxes to regulate basal calcium channel expression in a negative feedback loop may be inherently problematic (Rosati & McKinnon, 2004). In such a system, a sustained fall in calcium influx would result in a compensatory increase in current expression and a return to normal levels of calcium influx. Because calcium fluxes are the only established linkage between electrical activity and cell signalling/transcription, this mechanism would eliminate most of the useful information available to the cell about its own electrical activity, effectively short-circuiting this signalling pathway. It would seem more valuable to have the calcium channel and the fluxes that it mediates function as an independent indicator of electrical function, thereby preserving the information from calcium fluxes for other regulatory functions. The central role of the calcium channel in cell signalling is what makes this channel such a strong candidate for the evolution of a robust network to maintain basal channel expression levels relatively stable.

There may be particular selective pressure to maintain stable expression of the calcium channel in cardiac myocytes. This channel has an unusually complex role in the physiology of the myocyte that creates relatively tight constraints on both the upper and lower bounds of normal calcium current expression (Rosati et al. 2008). The current must be large enough to trigger excitation-contraction coupling (Rosati et al. 2008) but not so large as to result in calcium overload (Muth et al. 2001; Rosati et al. 2008). These constraints may create selective pressure for the evolution of mechanisms that produce more effective buffering of calcium channel expression than is seen for many other channels (Planells-Cases et al. 2000; Kuo et al. 2001; Ahern et al. 2001; Papadatos et al. 2002; Osanai et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2006; Brew et al. 2007; Tzingounis & Nicoll, 2008).

There are clearly limitations associated with the reliance on a passive buffering mechanism. A 280% increase in Cav1.2 mRNA expression in transgenic mice is buffered to a more modest 30–50% increase in calcium current (Muth et al. 1999, 2001). This increase is large enough, however, to induce hypertrophy, presumably secondary to calcium overload, which ultimately leads to heart failure, indicating an effective failure of the buffering system (Muth et al. 1999, 2001; Wang et al. 2009). A true homeostatic feedback system would be able to maintain close to constant levels of current expression over this relatively modest range of mRNA values. It is possible that the Cav1.2 heterozygous knockout mice will also be more prone to pathologies than wild-type mice, due to reduced calcium channel protein expression, when examined for longer time periods or under more stressful conditions.

The lack of effective response to the homozygous knockout of the Cav1.2 gene in the adult heart is also revealing. This is a life-threatening situation, where reasonable compensatory solutions exist, either up-regulation of expression of Cav1.3, which is expressed at relatively high levels in normal embryonic heart, or up-regulation of other calcium channel subunit genes. In addition, there are several potential feedback signals, including dramatically reduced calcium flux, contractility and cardiac output. Despite these apparently favourable circumstances, there is no effective compensatory response. Clearly, there is no generalized homeostatic regulatory system in the adult heart that can respond to changes in channel expression and/or physiological function in order to mediate a useful compensatory response.

Genetic mutations affecting the cardiac electrophysiological system are relatively rare in natural populations and are unlikely to have been a significant factor affecting the evolution of robustness in this system. This rarity almost certainly accounts in large part for the general fragility of the cardiac electrophysiological system to these kinds of genetic perturbations (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Chen et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1999; Fodstad et al. 2004). Genetic mutations, either natural or experimentally induced, can, however, reveal the robustness or fragility of a system to non-genetic perturbations (Wagner, 2007). The stability of calcium current expression following heterozygous Cav1.2 gene deletion suggests that there has been selective pressure to develop mechanisms to maintain stable levels of basal calcium current expression, either during the course of normal physiology or in common pathological conditions affecting the heart.

Acknowledgments

This work was upported by NIH grant HL-28958, AHA grant 0235467T and the Molecular Cardiology Institute at Stony Brook University.

Author contributions

B.R. and D.M. designed the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the paper. B.R. and D.M. performed the mRNA and protein experiments. B.R. performed the electrophysiology. Q.Y., M.S.L. and S.-R.L. bred the various mouse strains and performed genotyping. D.M., M.S.L., and Q.Y. performed the echocardiography. J.F. and T.J.K. designed and created the Cav1.2 floxed mouse. D.M and B.I. performed the modelling study. All authors approved the final version.

Supplementary material

Online Figure 1

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors

References

- Ahern CA, Powers PA, Biddlecome GH, Roethe L, Vallejo P, Mortenson L, Strube C, Campbell KP, Coronado R, Gregg RG. Modulation of L-type Ca2+ current but not activation of Ca2+ release by the γ1 subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor of skeletal muscle. BMC Physiol. 2001;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, Rios E. Nonlinear charge movement in mammalian cardiac ventricular cells. Components from Na and Ca channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:65–93. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Characteristics of calcium-current in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:929–937. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi I, Mikala G, Koch SE, Akhter SA, Schwartz A. The L-type calcium channel in the heart: the beat goes on. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3306–3317. doi: 10.1172/JCI27167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew HM, Gittelman JX, Silverstein RS, Hanks TD, Demas VP, Robinson LC, Robbins CA, McKee-Johnson J, Chiu SY, Messing A, Tempel BL. Seizures and reduced life span in mice lacking the potassium channel subunit Kv1.2, but hypoexcitability and enlarged Kv1 currents in auditory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:1501–1525. doi: 10.1152/jn.00640.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapados RA, Gruver EJ, Ingwall JS, Marsh JD, Gwathmey JK. Chronic administration of cardiovascular drugs: altered energetics and transmembrane signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H1576–H1586. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.5.H1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Kirsch GE, Zhang D, Brugada R, Brugada J, Brugada P, Potenza D, Moya A, Borggrefe M, Breithardt G, Ortiz-Lopez R, Wang Z, Antzelevitch C, O'Brien RE, Schulze-Bahr E, Keating MT, Towbin JA, Wang Q. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:293–296. doi: 10.1038/32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Piacentino V, Furukawa S, Goldman B, Margulies KB, Houser SR. L-type Ca2+ channel density and regulation are altered in failing human ventricular myocytes and recover after support with mechanical assist devices. Circ Res. 2002;91:517–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000033988.13062.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle BP, Anson BD, Rajamani S, January CT. Biology of cardiac arrhythmias: ion channel protein trafficking. Circ Res. 2004;94:1418–1428. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000128561.28701.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch C. The birth of a channel. Neuron. 2003;40:265–276. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodstad H, Swan H, Auberson M, Gautschi I, Loffing J, Schild L, Kontula K. Loss-of-function mutations of the K+ channel gene KCNJ2 constitute a rare cause of long QT syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit N, Le Bouter S, Szuts V, Varro A, Escande D, Nattel S, Demolombe S. Regional and tissue specific transcript signatures of ion channel genes in the non-diseased human heart. J Physiol. 2007;582:675–693. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ospina N, Tsuruta F, Barreto-Chang O, Hu L, Dolmetsch R. The C terminus of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.2 encodes a transcription factor. Cell. 2006;127:591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley RW, Lederer WJ. Properties of L-type calcium channel gating current in isolated guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98:265–285. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Conklin MW, Foell JD, Wolff MR, Haworth RA, Coronado R, Kamp TJ. Reduction in density of transverse tubules and L-type Ca2+ channels in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Yamada Y, Fukao M, Tsutsuura M, Tohse N. Regulation of Cav1.2 current: interaction with intracellular molecules. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;103:347–353. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0070012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koitabashi N, Bedja D, Zaiman AL, Pinto YM, Zhang M, Gabrielson KL, Takimoto E, Kass DA. Avoidance of transient cardiomyopathy in cardiomyocyte-targeted tamoxifen-induced MerCreMer gene deletion models. Circ Res. 2009;105:12–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Cheng CF, Clark RB, Lin JJ, Lin JL, Hoshijima M, Nguyen-Tran VT, Gu Y, Ikeda Y, Chu PH, Ross J, Giles WR, Chien KR. A defect in the Kv channel-interacting protein 2 (KChIP2) gene leads to a complete loss of Ito and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larionov A, Krause A, Miller W. A standard curve based method for relative real time PCR data processing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Golowasch J, Marder E, Abbott LF. A model neuron with activity-dependent conductances regulated by multiple calcium sensors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2309–2320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02309.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsberry BB, Czubryt MP, Dubo DF, Gilchrist JS, Docherty JC, Maddaford TG, Pierce GN. Effect of chronic administration of verapamil on Ca++ channel density in rat tissue. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:540–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsberry BB, Dubo DF, Thomas SM, Docherty JC, Maddaford TG, Pierce GN. Effect of high-dose verapamil administration on the Ca2+ channel density in rat cardiac tissue. Pharmacology. 1994;49:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000139213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughran JA, Juno CJ. Calcium channel blockade with verapamil. Effects on blood pressure, renal, and myocardial adrenergic, cholinergic, and calcium channel receptors in inbred Dahl hypertension-sensitive (S/JR) and hypertension-resistant (R/JR) rats. Am J Hypertens. 1988;1:255S–262S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.3.255s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M, Weissgerber P, Londono JEC, Molkentin JD, Nilius B, Flockerzi V, Freichel M. Temporally regulated inactivation of the loxP-targeted CaVβ2 gene in the adult mouse heart. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379(Suppl. 1):30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Merlie JP, Smith MM. Synthesis and assembly of acetylcholine receptor, a multisubunit membrane glycoprotein. J Membr Biol. 1986;91:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01870209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth JN, Bodi I, Lewis W, Varadi G, Schwartz A. A Ca2+-dependent transgenic model of cardiac hypertrophy: A role for protein kinase Cα. Circulation. 2001;103:140–147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth JN, Yamaguchi H, Mikala G, Grupp IL, Lewis W, Cheng H, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Cardiac-specific overexpression of the α1 subunit of the L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel in transgenic mice. Loss of isoproterenol-induced contraction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21503–21506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai M, Saegusa H, Kazuno AA, Nagayama S, Hu Q, Zong S, Murakoshi T, Tanabe T. Altered cerebellar function in mice lacking CaV2.3 Ca2+ channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadatos GA, Wallerstein PM, Head CE, Ratcliff R, Brady PA, Benndorf K, Saumarez RC, Trezise AE, Huang CL, Vandenberg JI, Colledge WH, Grace AA. Slowed conduction and ventricular tachycardia after targeted disruption of the cardiac sodium channel gene Scn5a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6210–6215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082121299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentino V, III, Weber CR, Chen X, Weisser-Thomas J, Margulies KB, Bers DM, Houser SR. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:651–658. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000062469.83985.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt GS, Dun W, Boyden PA. Remodeled cardiac calcium channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:373–388. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planells-Cases R, Caprini M, Zhang J, Rockenstein EM, Rivera RR, Murre C, Masliah E, Montal M. Neuronal death and perinatal lethality in voltage-gated sodium channel αII-deficient mice. Biophys J. 2000;78:2878–2891. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76829-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, Dong M, Cheng L, Liou SR, Yan Q, Park JY, Shiang E, Sanguinetti M, Wang HS, McKinnon D. Evolution of ventricular myocyte electrophysiology. Physiol Genomics. 2008;35:262–272. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00159.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, Dun W, Hirose M, Boyden PA, McKinnon D. Molecular basis of the T- and L-type Ca2+ currents in canine Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 2007;579:465–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, Grau F, Kuehler A, Rodriguez S, McKinnon D. Comparison of different probe-level analysis techniques for oligonucleotide microarrays. Biotechniques. 2004;36:316–322. doi: 10.2144/04362MT03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, McKinnon D. Regulation of ion channel expression. Circ Res. 2004;94:874–883. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124921.81025.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Spector PS, Keating MT. Spectrum of HERG K+-channel dysfunction in an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2208–2212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauro HM. Network dynamics. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;541:269. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-243-4_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder E, Byse M, Satin J. L-type calcium channel C terminus autoregulates transcription. Circ Res. 2009;104:1373–1381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder E, Magyar J, Burgess D, Andres D, Satin J. Chronic verapamil treatment remodels ICa,L in mouse ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1906–H1916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00793.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder F, Handrock R, Beuckelmann DJ, Hirt S, Hullin R, Priebe L, Schwinger RH, Weil J, Herzig S. Increased availability and open probability of single L-type calcium channels from failing compared with nonfailing human ventricle. Circulation. 1998;98:969–976. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, Penninger JM, Molkentin JD. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:270–283. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzingounis AV, Nicoll RA. Contribution of KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 to the medium and slow afterhyperpolarization currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19974–19979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810535105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. Robustness and Evolvability in Living Systems. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Papp AC, Binkley PF, Johnson JA, Sadee W. Highly variable mRNA expression and splicing of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel α subunit 1C in human heart tissues. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:735–745. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000230119.34205.8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Ziman B, Bodi I, Rubio M, Zhou YY, D'Souza K, Bishopric NH, Schwartz A, Lakatta EG. Dilated cardiomyopathy with increased SR Ca2+ loading preceded by a hypercontractile state and diastolic failure in theα1CTG mouse. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Tristani-Firouzi M, Xu Q, Lin M, Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Functional effects of mutations in KvLQT1 that cause long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:817–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JA, McKinney BC, John MC, Powers PA, Kamp TJ, Murphy GG. Conditional forebrain deletion of the L-type calcium channel CaV1.2 disrupts remote spatial memories in mice. Learn Mem. 2008;15:1–5. doi: 10.1101/lm.773208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Welling A, Paparisto S, Hofmann F, Klugbauer N. Enhanced expression of L-type Cav1.3 calcium channels in murine embryonic hearts from Cav1.2-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40837–40841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Mantegazza M, Westenbroek RE, Robbins CA, Kalume F, Burton KA, Spain WJ, McKnight GS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.