Abstract

Previous studies of resistance gene ecology have focused primarily on populations such as hospital patients and farm animals that are regularly exposed to antibiotics. Also, these studies have tended to focus on numerically minor populations such as enterics or enterococci. We report here a cultivation-independent approach that allowed us to assess the presence of antibiotic resistance genes in the numerically predominant populations of the vaginal microbiota of two populations of primates that are seldom or never exposed to antibiotics: baboons and mangabeys. Most of these animals were part of a captive colony in Texas that is used for scientific studies of female physiology and physical anthropology topics. Samples from some wild baboons were also tested. Vaginal swab samples, obtained in connection with a study designed to define the normal microbiota of the female vaginal canal, were tested for the presence of two types of antibiotic resistance genes: tetracycline resistance (tet) genes and erythromycin resistance (erm) genes. These genes are frequently found in human isolates of the two types of bacteria that were a substantial part of the normal microbiota of primates (Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes). Since cultivation was not feasible, polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were used to detect and characterize these resistance genes. The tet(M) and tet(W) genes were found most commonly, and the tet(Q) gene was found in over a third of the samples from baboons. The ermB and ermF genes were found only in a minority of the samples. The ermG gene was not found in any of the specimens tested. Polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that at least some tet(M) and tet(Q) genes were genetically linked to DNA from known conjugative transposons (CTns), Tn916 and CTnDOT. Our results raise questions about the extent to which extensive exposure to antibiotics is the only pressure necessary to maintain resistance genes in natural settings.

Introduction

The increase in incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has been attributed to the widespread use of antibiotics in medicine18 and agriculture.2,25,26 In fact, antibiotic-resistant intestinal bacteria, at least in the minority populations of enterics and enterococci, have been found widely in environments where antibiotics are used. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria have also been found in settings where antibiotic exposure is expected to be rare or nonexistent. Surveys of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in wild animals have detected resistant bacteria in intestinal contents.1,7,9,28 These studies, however, have also been limited to the numerically minor bacterial populations.

The assertion that antibiotic use leads to an increase in the incidence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria seems reasonable because the use of antibiotics not only selects for maintenance of resistant strains but also in some cases can actually stimulate the transfer of mobile elements. For example, tetracycline stimulates the transfer of such conjugative transposons (CTns) as the Bacteroides element CTnDOT and the gram-positive element Tn916.4,20,23 Among the genes most often tied to broad host range horizontal gene transfers across genus and species lines are the ribosome protection type of tetracycline, exemplified by tet(M), tet(Q), and tet(W)3,13,14,22 and some of the methylase type erythromycin resistance genes, exemplified by ermB, ermF, and ermG.12,27 The tet(M), tet(W), ermB, and ermG genes are most often found in the Firmicutes, and the tet(Q) and ermF genes are found widely in the Bacteroidetes. Both of these groups are prominent members of the natural microbiota of humans and animals.

Recently, we had the opportunity to test some specimens taken from the vaginal canals of two types of primates, baboons (Papio hamadryas) and mangabeys (Cercocebus atys). These samples had been obtained originally as part of a study to define the vaginal microbiota of these primates.16 Baboons have been used extensively as models for the study of reproductive conditions such as endometriosis, so defining the microbiota of these primates has medical significance. Most of the animals included in this study came from a captive colony that is maintained for research purposes. Although these animals are exposed to humans, they are rarely, if ever exposed, to antibiotics. Samples were also obtained from a small number of wild baboons. The wild baboons had minimal contact with human settlements and thus should have had no direct contact with antibiotics.

A major difference between this study and previous studies of resistance genes in wild animals was that we have used a genomic approach, based on results of a study of the population structure of the primate vaginal microbiota, to target the types of resistance genes found in the numerically predominant bacterial populations. We report here that some of these antibiotic resistance genes, such as tet(M) and tet(W), are surprisingly widespread in primates, both in wild and captive populations, and in some cases are associated with known CTns.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Vaginal specimens were taken from 34 adult female baboons (P. hamadryas) housed in the Southwest National Primate Research Center (San Antonio, TX) and 9 adult female mangabeys (C. atys) housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. Specimens were also taken from five wild adult female baboons from the Amboseli Baboon Research Project in Amboseli, Kenya. In the case of the captive baboons, vaginal tract sample collection was performed following approved Institutional Animal Care & Use Committe (IACUC) protocols. All primates received comparable diet and they were housed together with others of the same species. The concrete floors of the cage area were regularly cleaned with hoses. All captive primates were fed a diet of Purina monkey chow (no less than 5% protein), fruit, and water. No animal received antibiotic treatment during the several months before our sampling. Primate manipulation for sampling was carried out strictly after animals were injected intramuscularly with ketamine hydrochloride at a dosage of 10–15 mg/kg body weight.

In the case of the wild baboons, the primates subsisted entirely on wild foods. They were never fed, and were not handled in any way, except on the occasions when they were darted to sedate them for sample collection. Most of the subjects in this study had never been darted before. Wild baboon sampling was performed according to Princeton University (#1547) and Duke University (#A1830-06-04) IACUC protocols.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

The samples tested were swab samples. Swab samples were obtained with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator that was inserted 0.5–2 cm into vaginal canal and rotated 360°, thus sampling a large portion of the outer 1/3 of the tract. The swab tip was subsequently placed into a collection tube containing 1 ml sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) and frozen immediately (captive baboons) or RNA later (wild baboons). Total DNA was isolated from baboon vaginal samples by phenol extraction.10 DNA was stored at −20°C.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification, cloning, and DNA sequencing

Resistance gene DNA was amplified using the Go Taq DNA polymerase kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Primers that detected internal segments of tet(M), tet(Q), tet(W), ermB, ermF, and ermG (Table 1) were used in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR was as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes; followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds of denaturation, 42–55°C for 30 seconds for annealing, and 68°C for 1 minute of elongation; a final elongation step of 68°C for 5 minutes concluded the PCR. The products of PCR were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel to observe PCR products. Amplicons from PCR that contained the correct size bands were cloned into the pGEMT EAZY vector (Promega) and transformed into MCR Escherichia coli cells. Cells were plated on Luria broth + Ampicillin 50 μg/ml (Ap) + X-gal 40 μg/ml. Transformant colonies that contained PCR inserts (white colonies) were grown overnight in liquid Luria broth + Ap. Plasmid DNA was extracted from liquid cultures and digested with EcoRI to verify that clone contained an insert of the correct size. Plasmid DNA was sequenced and analyzed at the University of Illinois Biotechnology Center.

Table 1.

Primers Used in This Study

| Primer name | Primer sequence | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|

| tet(M) Fwd | GACACGCCAGGACATATGG | 11 |

| tet(M) Rev | TGCTTTCCTCTTGTTCGAG | |

| tet(M) Fwd#2 | GGAGCGATTACAGAATTAGGAAGCG | Used to amplify and internal region of the tet(M) gene. Amplicon size is 1,805 bp (Robert Jeters, this study) |

| tet(M) Rev#2 | TCTATCCGACTATTTGGACGACGG | |

| tet(Q) Fwd | GATACICCIGGICAYRTIGAYTT | 6 |

| tet(Q) Rev | GCCCARWAIGGRTTIGGIGGIACYTC | |

| tet(W) Fwd | CGTTGATTTGCAGAGCGTGGTTCA | Used to amplify and internal region of the tet(W) gene. Amplicon size is 445 bp (Robert Jeters, this study) |

| tet(W) Rev | AGCGTTCCGCTGTATAACCGTAGA | |

| ermB Fwd | GAAAAGGTACTCAACCAAATA | 24 |

| ermB Rev | AGTAACGGTACTTAAATTGTTTAC | |

| ermF Fwd | TACGGGTCAGCACTTTACTATT | Used to amplify and internal region of the ermF gene. Amplicon size is 748 bp (Terry Whitehead, unpublished) |

| ermF Rev | GACAACTTCCAGCATTTCCA | |

| ermG Fwd | ACATTTCCTAGCCACAATC | Used to amplify and internal region of the ermG gene. Amplicon size is 438 bp (unpublished) |

| ermG Rev | GCGATACAAATTGTTCG | |

| tet(M)/Tn916 Fwd | TACTACCGGTGAACCTGTTTGCCA | Used to amplify the tet(M) gene and the orf9 of Tn916. Amplicon size is 472 bp (Robert Jeters, this study) |

| tet(M)/Tn916 Rev | TTTAGCCAGCGGTATCAACGAAGC | |

| tet(Q)/rteA Fwd | TGTGGACATTCTCGAACCGATGCT | Used to amplify the tet(Q) gene and the rteA gene of CTnDOT. Amplicon size is 435 bp (Robert Jeters, this study) |

| tet(Q)/rteA Rev | CTATCTCCTGCCATTCATAGAGGC |

Phylogenetic analysis

Comparative analysis of the tetracycline-resistant gene sequences was performed using a set of tools available in the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment programs.5 Global alignments of these data sets were performed using default settings to calculate distances between all pair of sequences, and the Neighbor-joining method17 was applied for generation of a phylogenetic tree depicting tetracycline resistance genes' relationships.

Results and Discussion

Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes

Cultivation of bacteria from the vaginal microbiota, especially the numerically predominant bacteria, requires a variety of media and conditions at the site of collection; therefore, cultivation was not feasible. Accordingly, to analyze the resistance genes found in these samples, a cultivation-independent approach was used. This approach was also appealing because the wide range of interbacterial transfers that can occur raises questions about whether the resistance genes themselves are a more appropriate focus of attention in surveys such as this one than resistant strains of a particular bacterial species.19 One can argue that the existence of a resistance gene in a bacterial strain does not prove that the strain is resistant, but as long as the gene is intact, mutations in a promoter region can cause it to be expressed. Even simple mutations within the gene such as stop or nonsense codons can be easily corrected by mutation. Thus, the presence of a particular type of resistance gene indicates that this type of resistance is a part of the resistance potential of the population.

Previous 16S rRNA analysis of these specimens indicated that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were major groups in the primate vaginal microbiota.16 Accordingly, we chose to focus on genes such as tet(M), tet(Q), tet(W), ermB, ermF, and ermG that have been found widely in human and farm animal isolates of these groups of bacteria. The main question we were able to ask, given the lack of cultivation and the fact that we are investigating a bacterial population rather than individual bacteria was, Are antibiotic resistance genes found at all in such animals? The vaginal microbiota was a good target for this question because a direct effect of diet was eliminated. To assess the extent to which the target resistance genes were present, an interior region of each of the chosen genes was amplified. To make sure that the amplification reaction had produced the desired gene segment, PCR amplicons were cloned and sequenced.

Unexpectedly, some resistance genes were very widespread. The tet(M) and tet(W) genes were found in all three groups of the primates (captive baboons, wild baboons, and captive mangabeys; Table 2). The tet(M) gene was found in virtually all of the specimens tested. The tet(W) gene was also found in a high proportion of the samples from captive baboons, but less frequently in the wild baboons. About half of the mangebey samples tested positive for tet(W).

Table 2.

Detection of tet(M), tet(W), tet(Q), ermB, ermF, and ermG Genes in Wild and Captive Baboons and in Captive Mangabeys

| |

Captive baboons |

Wild baboons |

Mangabeys |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic resistance gene tested for | No. of primates tested | No. of primates carrying gene | No. of primates tested | No. of primates carrying gene | No. of primates tested | No. of primates carrying gene |

| tet(M) | 34 | 28 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 8 |

| tet(W) | 34 | 32 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 5 |

| tet(Q) | 34 | 13 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| ermB | 34 | 6 | NA | NA | 9 | 0 |

| ermF | 34 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 1 |

| ermG | 34 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

All positive results were verified by sequence analysis. NA, not attempted due to lack of sample.

In contrast to widespread distribution of the tet(M) and tet(W) genes, tet(Q) genes were found only in the captive baboons, not in the wild baboons or mangebeys. This distribution of tet genes was consistent with the predominance of Firmicutes [tet(M) and tet(W)] in the primate microbiota. Also, since the captive animals were also fed a similar diet (monkey chow as the base), the observation that none of the mangabeys harbored tet(Q) supports the contention that the resistance genes were unlikely to be coming in through the animals' food or being transmitted to the vaginal tract through contamination with feces or spilled food.

Erythromycin resistance genes were found in fewer primate samples. The ermF gene was found in all three groups of primates but was less frequently detected than tet(M) or tet(W). The ermB gene was found in samples from captive baboons only. We were unable to test the wild baboons for the presence of ermB because the amount of sample available from the wild baboon was very low and there was not enough left to test when we got to this set of primers. The only antibiotic resistance gene not detected in any of the samples was the ermG gene. The ermG gene was originally found in a Bacillus sphaericus strain isolated from a bird, but in a recent study of resistance genes in the feces of pigs fed tylosin, a member of the erythromycin family of macrolide antibiotics, this gene was detected.27

Sequence comparison of tet(M) and tet(Q) genes

Only an interior segment of individual resistance genes was sequenced because the main purpose of sequence analysis was to confirm that the PCR primers were amplifying the desired sequences. Also, these sequences allowed us to ascertain that the tet(M) and tet(Q) genes we were amplifying were not arising from contamination with DNA from laboratory strains. Since tet(M) was so widespread, we decided to use the tetM sequences to answer two further questions. First, how diverse were the sequences and were they closely related to sequences found in human or food isolates? Second, did the sequences we obtained (393 bp of a 1,920 bp gene in all cases, 1,429 in a subset of five genes) contain stop codons or missense mutations that would render the gene product inactive?

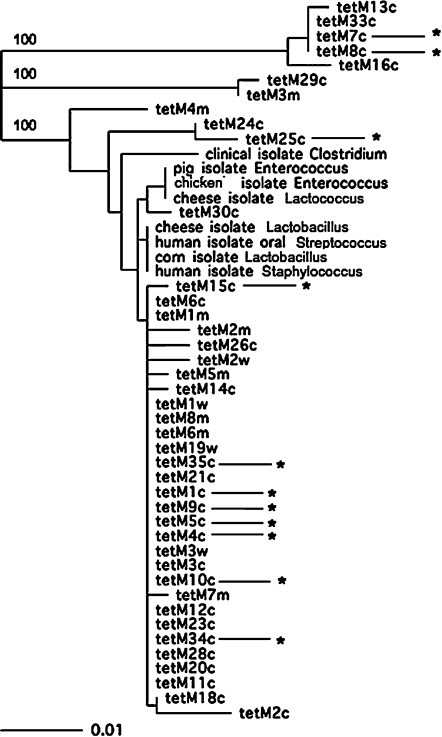

A phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the 49 short tet(M) sequences is shown in Fig. 1. There was diversity at the DNA sequence level, but this diversity consisted in most cases of only a few base pair differences. Most of the sequences were very similar to each other, an observation that has been made in the case of human, food, and farm animal isolates. There were, however, some genes whose internal sequences differed significantly from most of the other sequences. This can be seen in Fig. 1 in the 100% confidence bootstrap values on two of the map branches. These sequences all came from captive baboons or mangabeys. The diversity seen in the tet(M) sequences seemed to be greater than that reported previously in humans, food, or farm animals. Only a few sample sequences were included in the tree shown in Fig. 1 to make the tree readable, but they were chosen because they were representative of sequences in the databases. The tet(M) sequences in the sequence databases are probably not a good indication of the true sequence diversity of these genes because they are heavily skewed toward isolates from human clinical and food specimens. It will be informative in the future to examine genes of this type obtained from a greater variety of sources.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree composed of sequences from primates used in this study and tet(M) sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The number behind tet(M) indicates the sample number of the primate. The “c” denotes that it is a captive baboon. The “w” denotes that it is a wild baboon. The “m” denotes that it is a captive mangabey. The bar shows the length of the bar that corresponds to 1%. Asterisks indicate the tet(M) alleles that were linked to Tn916 in that baboon. The bootstrap values were computed with ClustalW, 100 repetitions. Only the significant bootstrap figures are shown. Confidence figures are shown only for branches that were significant. Figures for the other branches were less than 70% and were therefore not considered significant. To make the tree easier to read, only a few nonprimate sequences were included in this tree to provide a reference point for comparison, but most sequences in the databases clustered with these sequences.

A comparison of the amino acid sequences revealed only one sequence that contained a stop codon. This finding indicates that the genes might be functional. We obtained longer sequences (1,429 bp) from a subset of five of the tet(M)-containing samples. There was one gene that had a stop codon in it. Thus, if we had sequenced the entire gene, the number of genes with stop codons might have been larger, but the number of potentially active gene products was still very high. Similar results were obtained with the tet(Q) amplicons (618–844 bp; data not shown). Our findings indicate that these resistance genes were mostly functional or could become functional through one or a few mutations. That is, the genes are very stably maintained and are not easily lost even in the absence of antibiotic selection.

We did a similar analysis on our tet(Q) sequences because tet(Q), in contrast to tet(M), which has been found mainly in Firmicutes, is found mainly in Bacteroidetes and thus represents another bacterial phylum. The results of this analysis were similar to those for tet(M). That is, there was limited but significant diversity among the alleles sequenced and most of the genes appeared to lack stop codons.

Association of tet(M) and tet(Q) with mobile elements

Another type of question that can be addressed using a genomic approach is whether or not some of the genes were associated with known mobile elements. Only a relatively few mobile elements have been studied in depth. There is, however, considerable information about two types of CTns that carry the resistance genes targeted in this study: tet(M) (Tn916) and tet(Q) (CTnDOT). Since CTns are integrated into the chromosome, there is no simple procedure similar to a plasmid preparation to detect and isolate them. A way to establish whether the tet(M) or tet(Q) is associated with one of these CTns is to use one primer that is anchored in the resistance gene and another that is anchored in the sequence outside the gene on known examples of the CTn. PCR assays were done using primers that amplify the adjacent region flanking an antibiotic resistance gene of interest. In the case of tet(M), primers were designed to amplify the 3′ end of the tet(M) gene through the corresponding flanking region of orf9 on Tn916. In the case of tet(Q), primers were designed to amplify the 3′ end of the tetQ gene through the flanking rteA gene of CTnDOT. The sequences amplified have only been found on Tn916 and CTnDOT type elements, respectively, and are not widespread among other conjugative transposons or conjugative plasmids.8,15,21 Twelve of the 28 tet(M)-positive samples from the captive baboons tested positive for the presence of Tn916 sequences linked to tet(M). Six of 13 tet(Q)-positive captive baboon samples tested positive for the presence CTnDOT-like mobile elements. In contrast to the captive baboons, none of 8 tet(M)-positive mangabey samples tested positive for the presence of Tn916. Since none of the mangabey samples tested positive for tet(Q), linkage to CTnDOT was not assessed. There was insufficient sample to allow testing of the tet(M)-positive samples from the wild baboons.

These results indicate that not just resistance genes but also mobile elements that carry them are found in nonhuman primates. The estimate of the number of tet(M) and tet(Q) genes linked to a known CTn may actually be an underestimate. Little is known about sequence variation in the regions of Tn916 and CTnDOT used in this analysis. Accordingly, the primers designed on the basis of known sequences in these regions may fail to amplify sequences in some elements that are closely related to but not identical to Tn916 or CTnDOT. Sequence analysis of the regions amplified showed that there was enough sequence diversity to show that the resistance genes and their associated mobile elements were not part of a clonal expansion of a particular strain. Another limitation of this analysis is that we could not ascertain from the small amount of Tn916- and CTnDOT-associated sequence obtained whether the CTns were likely to be active.

Sequence variation in the tet(M) genes within an individual primate's bacterial community

To assess intraindividual variation within an animal, four additional clones of the tet(M) gene from the same primate sample were sequenced and compared. Four baboons were selected (three captive and one wild) and analyzed to see if there was a difference in identity at the nucleotide level. In the captive baboons, single-nucleotide differences between different clones were detected. However, these single-nucleotide changes occurred at different locations throughout the gene. A similar result was seen in the case of the one wild baboon sequence. Thus, there is some sequence variability among tet(M) genes within the same animal.

Since these small regions of the tet(M) gene showed sequence variation, a limited number of larger tet(M) sequences were obtained and evaluated for sequence diversity. These larger sequences, which span 73% of the tet(M) gene (1,429 bp) exhibited a larger range of nucleotide differences. Differences of up to 43 nucleotides were seen between tetM genes from two different primates, although many of the larger sequences exhibited only a couple of nucleotide substitutions between primate samples.

A limitation of the study described here is that it is only possible to answer the question of whether the genes were present. It does, however, have the strength that it allows us to sample the numerically major bacteria, many of which may be difficult or impossible to cultivate at the present time. Because we were only asking whether the genes were present, statistical analysis was not appropriate. Also, of necessity, the number of samples available was limited.

We did not attempt to quantify the resistance genes because it is the presence of these genes rather than their abundance that is important for predicting resistance potential of the population. Exposure to antibiotics would quickly increase the concentration of resistance genes if they are present. What is not clear is how these genes came to be present in the first place. In the case of the captive animals, one possible explanation would be indirect spread of resistance genes from human caretakers or from the diet, but this explanation does not work in the case of the wild baboons. Another possibility is that there are selective pressures other than administered antibiotics that select for the acquisition and maintenance of tet and erm genes. There are antibiotic-producing organisms in soil, but the level of antibiotics in most soils is far too low to act as a significant selective pressure.

A question that could be answered by this type of study is whether the resistance genes we found were genetically linked to a mobile element, a linkage that suggests that the gene could move readily within the animal once it was present. In many of the specimens tested, tet(M) and tet(Q) were linked to CTns that have been found in humans. The number testing positive for linkage to a CTn may be an underestimate if small differences in sequence prevented effective binding of one of the primer seated in the CTn. The linkage of tet(M) to a mobile element is particularly interesting in view of the fact that the Firmicutes found in the primate vaginal microbiota were not predominantly lactobacilli, as in the case of humans, but other gram-positive bacteria such as clostridia. Although we cannot conclude that these CTns are active, it is clear that the genes were associated at one time with CTns known to be active in other bacterial isolates. Not enough is known about the transmissible elements that carry the erm genes to allow this sort of analysis.

The ermF gene has been found on CTnDOT and some related CTns, but it is present as an insertion of unknown origin. Also, ermF has been found on plasmids unrelated to CTnDOT. So, associating ermF with a mobile element was not attempted. Nonetheless, the results showing that tet(M) and tet(Q) may be linked to mobile elements suggest that these genes may have come into the animal microbiota via conjugation, although the source is unknown. The fact that there is DNA sequence variation among tet(M) and tet(Q) alleles indicates that there have been multiple acquisitions. The virtual amino acid sequence identity of Tet(M) proteins encoded by the tet(M) genes and Tet(Q) proteins encoded by the tet(Q) genes indicates that there is some sort of selective pressure to maintain the structure and function of these proteins.

It is interesting that the transfer of both Tn916 and CTnDOT is stimulated by tetracycline. This suggests that tetracycline or some chemically similar compound has contributed to the transfer into the animal vaginal microbiota. Yet, as far as can be determined, these animals have not been exposed to tetracycline. Tetracyclines have been found in ground water, especially around human sewage treatment plants and farms where drugs like tetracycline are used. Perhaps the primate colonies in the United States had this type of exposure, but the wild baboons should not have encountered this type of selection. We have tested plant compounds, flavones and flavonoids, that have structures similar to tetracycline, but we have not yet found any that stimulate the transfer of CTnDOT the way tetracycline does (unpublished data). What our results suggest is that there are factors that favor transfer of conjugative elements and promote maintenance of transferred resistance genes, but these factors may not be antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant RR-00167 from the National Science Foundation and by Grant AI22383 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Susan Alberts and Dr. Jeanne Altmann for sharing the wild primate samples. Sample collection in Amboseli was supported by National Science Foundation Grants BCS-0323553 and BCS-0323596 to S.C. Alberts and J. Altmann; permission and logistical assistance for the work in Amboseli was granted by the Office of the President of the Republic of Kenya, the Kenya Wildlife Service, and the Institute of Primate Research, Kenya. The Yerkes National Primate Research Center is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RR-00165. We thank the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research for access to baboons. Funding for data collection was provided by the University of Illinois Research Board.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Anderson J.F. Parrish T.D. Akhtar M. Zurek L. Hirt H. Antibiotic resistance of enterococci in American bison (Bison bison) from a nature preserve compared to that of Enterococci in pastured cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:1726–1730. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02164-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo F.J. Baker N.L. Olsen S.J. Anderson A. Barrett T.J. Antimicrobial use in agriculture: controlling the transfer of antimicrobial resistance to humans. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2004;15:78–85. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burdett V. Streptococcal tetracycline resistance mediated at the level of protein synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1986;165:564–569. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.564-569.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celli J. Trieu-Cuot P. Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:103–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chenna R. Sugawara H. Koike T. Lopez R. Gibson T.J. Higgins D.G. Thompson J.D. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clermont D. Chesneau O. De Cespédès G. Horaud T. New tetracycline resistance determinants coding for ribosomal protection in streptococci and nucleotide sequence of tet(T) isolated from Streptococcus pyogenes A498. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:112–116. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa D. Poeta P. Saenz Y. Vinue L. Coelho A.C. Matos M. Rojo-Bezares B. Rodrigues J. Torres C. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolates recovered from wild animals. Microb. Drug Resist. 2008;14:71–77. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flannagan S.E. Zitzow L.A. Su Y.A. Clewell D.B. Nucleotide sequence of the 18-kb conjugative transposon Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1994;32:350–354. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilliver M.A. Bennett M. Begon M. Hazel S.M. Hart C.A. Antibiotic resistance found in wild rodents. Nature. 1999;401:233–234. doi: 10.1038/45724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim T.K. Thomas S.M. Ho M. Sharma S. Reich C.I. Frank J.A. Yeater K.M. Biggs D.R. Nakamura N. Stumpf R. Leigh S.R. Tapping R.I. Blanke S.R. Slauch J.M. Gaskins H.R. Weisbaum J.S. Olsen G.J. Hoyer L.L. Wilson B.A. Heterogeneity of vaginal microbial communities within individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:1181–1189. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00854-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacroix J.M. Walker C.B. Detection and prevalence of the tetracycline resistance determinant Tet Q in the microbiota associated with adult periodontitis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1996;11:282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclercq R. Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manavathu E.K. Hiratsuka K. Taylor D.E. Nucleotide sequence analysis and expression of a tetracycline-resistance gene from Campylobacter jejuni. Gene. 1988;62:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikolich M.P. Shoemaker N.B. Salyers A.A. A Bacteroides tetracycline resistance gene represents a new class of ribosome protection tetracycline resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;36:1005–1012. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.5.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice L.B. Tn916 family conjugative transposons and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1871–1877. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera A.J. Frank J. Stumpf R. Leigh S. Wilson B. Reich C. Olsen G. Salyers A. A preliminary look at high inter–individual microbial diversity among baboon vaginal ecosystems. Abstract presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, 107th General Meeting; Toronto, Canada. May 21–25;; 2007. Abstract no. N-112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitou N. Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salyers A.A. Shoemaker N.B. Conjugative transposons: the force behind the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among Bacteroides clinical isolates. Anaerobe. 1995;1:143–150. doi: 10.1006/anae.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salyers A.A. Vlamakis H. Shoemaker N.B. Ecology of antibiotic resistance genes. In: White D.G., editor; Alekshun M.N., editor; McDermott P.F., editor. Frontiers in Antimicrobial Resistance: A Tribute to Stuart B. Levy. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoemaker N.B. Salyers A.A. Tetracycline-dependent appearance of plasmidlike forms in Bacteroides uniformis 0061 mediated by conjugal Bacteroides tetracycline resistance elements. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:1651–1657. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1651-1657.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoemaker N.B. Vlamakis H. Hayes K. Salyers A.A. Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:561–568. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.561-568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sougakoff N. Papadopoulou B. Nordman P. Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence and distribution of gene tetO encoding tetracycline resistance in Camphylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1987;44:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens A.M. Shoemaker N.B. Li L.Y. Salyers A.A. Tetracycline regulation of genes on Bacteroides conjugative transposons. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:6134–6141. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6134-6141.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutcliffe J. Grebe T. Tait-Kamradt A. Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Bogaard A.E. London N. Driessen C. Stobberingh E.E. Antibiotic resistance of faecal Escherichia coli in poultry, poultry farmers and poultry slaughterers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;47:763–771. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Looveren M. Daube G. De Zutter L. Dumont J.M. Lammens C. Wijdooghe M. Vandamme P. Jouret M. Cornelis M. Goossens H. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Campylobacter strains isolated from food animals in Belgium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48:235–240. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y. Wang G.R. Shoemaker N.B. Whitehead T.R. Salyers A.A. Distribution of the ermG gene among bacterial isolates from porcine intestinal contents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4930–4934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4930-4934.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiggins B.A. Discriminant analysis of antibiotic resistance patterns in fecal streptococci, a method to differentiate human and animal sources of fecal pollution in natural waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:3997–4002. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3997-4002.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]