Abstract

The signed informed consent form provides documentary evidence that the patient has given informed consent to participate in a clinical trial and that the patient has been given the requisite information. However, this document must not only provide the necessary information, it must also be provided in a way that can be understood by the patient. Non conclusive information suggests that research participants frequently may not understand the information presented during the informed consent procedure. Comprehension requires that the patient be able to understand the information presented and have the time and opportunity to read, evaluate and consider the information presented.

A shortened Informed Consent Form, with information that a reasonable person would want to understand along with specific information that the person wants in particular would be a good option to improve understanding or comprehensibility. Additional informational meetings with a qualified person like a counselor could help in comprehension. Questionnaires designed to test comprehension of patient, peer review, patient writing the salient features could help evaluate the comprehensibility of the Informed Consent Form.

Keywords: Informed consent, Clinical research, Readability, Comprehension

Introduction

Informed Consent is the most fundamental principle in the conduct of clinical trials. For the consent to be informed, the patient must receive and comprehend appropriate information that will help him make an autonomous decision. While this information can be given to the patient in many ways, including oral discussion with the investigator and his study team, multimedia presentations and other methods, the most common and preferred method is that of the written informed consent forms.

The signed informed consent form provides documentary evidence that the patient has given informed consent to participate in a clinical trial and that the patient has been given the requisite information. Regulations in most countries require that a written informed consent be taken in all but some rare exceptions. However, this document must not only provide the necessary information, it must also be provided in a way that can be understood by the patient. Whether the consent forms used in the clinical trials and their translations fulfill this need is what this review examines and hopes to offer suggestions that might improve understanding or comprehensibility.

Review

To make a consent form that not only complies with the regulatory requirements, but also gives complex scientific information in a way that is comprehensible to a lay person is a formidable challenge. Besides giving medical information to the patient, the consent form must also convey complexities like trial design, randomization, placebo, possible risks and benefits, treatment options, rights to withdraw, and so forth.

Comprehension requires that the patient be able to understand the information presented and have the time and opportunity to read, evaluate and consider the information presented.

Readability of the consent form, while contributing to the comprehension, is not the same as comprehension. An easy to read text might be difficult to comprehend if poorly written. However, readability does affect the willingness to read the text and hence could improve comprehension. The FDA has stated the responsibility of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as “The IRB should ensure that the informed consent document properly translates complex scientific concepts into simple concepts that the typical subject can read and comprehend”.1

In India, we have translations into many languages of an informed consent document that was originally in English. Often, these are literal translations and do not capture the true meaning of concepts or phrases and the nuances of the original document changes on translation. Besides, the language used in the translations is of a higher standard than what a lay person with average education might understand.

The length of the consent form is another issue that needs to be examined. Many consent forms are 15 to 20 pages long. The length by itself might act as a deterrent for the form to be read. Besides, to simply read a document that is 20 pages long would mean a time spent of approximately 60 minutes. In a clinical setting, this can be a considerable amount of time and the total time spent in the consenting process might be reduced, with the patient's queries not getting addressed adequately. Besides the amount of time spent, too much of information may hinder the understanding of information that is relevant to the patient. It is no surprise that in studies done on the Informed Consent Form, it was found that patients prefer simpler and easier to read Informed Consent Forms that can provide them the necessary information to make a decision regarding participation in the trial.2

Another aspect of informed consent is what information in particular needs to be sufficiently understood. If we consider that the standard practice (information that the professional community deems appropriate) is not the same as that which the subject actually wants, then we are left with the reasonable person standard (the information that a reasonable person would want to understand) and the subjective standard (information that this particular person wants to understand). A combination of giving the information that a reasonable person would want along with any specific information that the person wants in particular could be a good option.3

A simple mechanism of reducing the reading difficulty level is by replacing, wherever possible, technical terms with common terms. Using tools like outlining, bullet points, a large typeface and diagrams can help the reader to follow complex concepts. Using active verbs rather than the passive voice, short sentences and frequent paragraphing can make text simpler. Several Computer software packages allow rapid analysis of the Readability score. Most Ethics Committees recommend a readability score of Grade 8. However, often the actual readability may differ from the prescribed standard.4 Besides, the readability may not reflect appropriately on the comprehensibility of the consent form.5

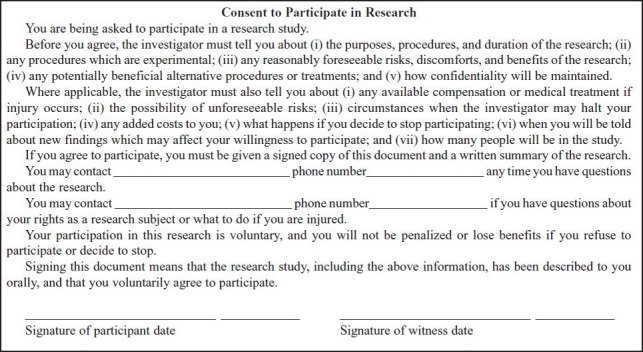

Appendices for more information are attached as follows

-

(i)

the purposes, procedures, and duration of the research

-

(ii)

any procedures which are experimental

-

(iii)

any reasonably foreseeable risks, discomforts, and benefits of the research

-

(iv)

any potentially beneficial alternative procedures or treatments

-

(v)

how confidentiality will be maintained

-

(vi)

any available compensation or medical treatment if injury occurs

-

(vii)

the possibility of unforeseeable risks

-

(viii)

circumstances when the investigator may halt your participation

-

(ix)

any added costs to you

-

(x)

what happens if you decide to stop participating

-

(xi)

when you will be told about new findings which may affect your willingness to participate

-

(xii)

number of participants in the study

Non conclusive information suggests that research participants frequently may not understand the information presented during the informed consent procedure. A questionnaire can be given to the patient at the end of the consenting procedure to evaluate comprehensibility.6

Usually, a signed consent form is supposed to mean that the patient has read and understood the form. However, besides signing the consent form if the patient writes the salient features in his/her own handwriting, e.g. that he understands that he may get a placebo instead of active treatment, and it will ensure that these points are focused upon.

Peer review of the consent form including review by lay persons (i.e. non healthcare professionals) may help in ensuring that the consent form meets the needs of the patient population who might be included in the trial. This will be especially helpful in assessing comprehensibility of translations.

Many countries have a short consent form, where translated versions of the full consent form are not available. 21 CFR, A suggestion is, to have short Informed Consent Forms which cover the crucial points only and refer the patients to appendices with further information that might be relevant or of interest to them. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Short video capsules about patient rights in waiting areas to educate them about clinical research and their rights as a subject may serve as a useful tool. Media can also play an important role in disseminating this knowledge. However, studies have suggested that multimedia intervention may not consistently increase comprehension, besides being expensive.7 Using a standard consenting process with an extra meeting with a qualified person, who need not be the investigator, is the most reliable method of increasing understanding.7 A large amount of complicated information during one meeting may be difficult to comprehend. The addition of information sessions with a counselor could significantly improve participants’ comprehension of the consent form.8

Conclusion

There is ample evidence to suggest that the informed consent forms and their translations are far too long and complex for the lay person to read and comprehend. Various methods to simplify these forms and to increase comprehension have been suggested. An intervention study with simplified consent forms could be undertaken to study the potential benefits of the simplified form.

References

- 1. 21 CFR 50.20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dresden G.M, Levitt M.A. Modifying a standard industry clinical trial consent form improves patient information retention as part of the informed consent process. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001;8(3):246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baruch A. Vol. 5. IRB: Ethics and Human Research; 2001. Brody, Making Informed Consent Meaningful; pp. 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael K, Paasche-Orlow, Holly A, Taylor, Frederick L. Brancati, Readability Standards for Informed-Consent Forms as Compared with Actual Readability. NEJM. 2003;348:721–726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessica Ancker. Ancker, Assessing patient comprehension of informed consent forms, Controlled Clinical Trials. 2004;25(1):72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller C, et al. Comprehension and recall of the informational content of the informed consent document: an evaluation of 168 patients in a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Research and Drug Development. 1994;8:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flory James, Emanuel Ezekiel. Interventions to Improve Research Participants Understanding in Informed Consent for Research: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald Daniel W, Marotte Cécile, Verdier Rose Irene, Johnson Warren D, Jr, Pape Jean William. Comprehension during informed consent in a less-developed country. Lancet. 2002;360:1301–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. 21 CFR 50.27(b) (2) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Short Form Consent – ENGLISH, Stanford University, Research Compliance Office, Human Subjects Research [Google Scholar]