Abstract

Aims:

This in vitro study compared the effects of different layering techniques on the microleakage of silorane-based resin composite using confocal laser scanning microscope.

Materials and Methods:

Forty caries free premolars extracted for orthodontic reasons were used. A class V cavity was prepared on the buccal surface in each of the premolars, with the gingival margin of the cavity being 1 mm above cementoenamel junction. The cavities were restored with a silorane-based resin composite (Filtek™ P90 Silorane Low Shrink Restorative, 3M ESPE) using two different layering techniques – split incremental and oblique layering technique. All samples were subjected to 1000 thermal cycles of 5°C/55°C in water with a 30 second dwell time, and after the procedure, the teeth were immersed in 0.6% aqueous rhodamine dye for 48 hours. Sectioned samples were examined under a Confocal Fluorescence Imaging Microscope (Leica TCS-SP5, DM6000-CFS) at 10× magnification, and microleakage scores were analyzed statistically using paired “t” test and Mann–Whitney test. Width of interface between the tooth surface and resin composite was measured using a digital scale (Snagit digital scale).

Results:

Microleakage was seen along the entire perimeter of restoration irrespective of the layering technique used. The microleakage score was same in both the groups. Statistical analysis of width of interface showed significant difference between the two layering techniques. The width was significantly less in split incremental technique, indicating less polymerization shrinkage.

Conclusions:

This in vitro study showed that the silorane-based resin composite shows microleakage irrespective of the layering technique used for class V cavities. However, this problem can be minimized significantly by using split incremental technique for restoration of class V lesions.

Keywords: Confocal microscopy, layering techniques, microleakage, silorane-based resin composite

INTRODUCTION

The demand for tooth-colored restorations has grown considerably during the last decade.[1] This phenomenon has been both a bane and a boon to the dental profession.[2] Despite technological advances, polymerization shrinkage of composites still remains a challenge and imposes limitations in their clinical use.

The setting of dental composites is accompanied by significant polymerization contraction, resulting in the generation of stresses within the material and at the tooth-restoration interface.[3] Polymerization contraction stress produces powerful forces that can separate the restoration from the tooth. Lack of sealing allows the occurrence of marginal microleakage.[4] Microleakage is defined as the passage of bacteria, fluids or molecules between a cavity wall and the restorative material applied to it.[5] Microleakage may cause hypersensitivity, recurrent caries and pulpal pathoses.[6] Besides pulpal irritation and secondary caries, microleakage also results in marginal discoloration.

Restoring cervical lesions with resin composites has always been a problem, especially where a very thin layer of enamel is present in the gingival margin for bonding. The higher organic content, tubular structure, fluid pressure and the low surface energy of dentin make bonding more critical. In addition, because of abfraction and debonding of restoration at this area, a proper and accurate method of restoration is needed.[7]

For the past several years, different techniques and materials have been examined to reduce microleakage in class V restorations. Incremental placement of light-cured composite resin has been suggested to reduce polymerization shrinkage and also improve marginal adaptation.[8]

Microleakage is commonly assessed in vitro using dye penetration studies to detect bond failure at the enamel–resin interface. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) is a non-destructive technique for visualizing subsurface tissue features. One of its advantages is the clear indication of leakage limits due to a lens focus that can occur some microns beneath the observed surface. This eliminates the stain spread caused by specimen sectioning and also avoids polishing artifacts that exaggerate dye penetration.[9]

The aim of the present study was to compare microleakage of silorane-based resin composite in class V cavities with split incremental and oblique layering technique using CLSM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This experimental study was done on 40 intact human premolars extracted for orthodontics reasons, with no crack, decay, fracture, abrasion, previous restorations, or structural deformities, which all were stored in normal saline and used within 2 weeks after extraction. After removing residual tissue tags, the specimens were cleaned with pumice. In the buccal surfaces of all the teeth, class V cavities were prepared with a No. 329 fissure bur under water spray.[10] The gingival margin of the cavity extended 1 mm above the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). The cavity dimensions were 3 mm in length, 2 mm in width and 1.5 mm in depth. The cavity depth was standardized using an acrylic resin template. The cavities were cleaned using pumice paste and then were rinsed with a water spray and gently dried.

Restorative procedures

After the preparations were completed, the teeth were randomly assigned to two groups of 20 teeth each.

Group I: Split incremental layering technique with silorane composite

This group consisted of 20 specimens obturated with a silorane restorative material (Filtek™ P90 Silorane Low Shrink Restorative, 3M ESPE) and its relevant adhesive.

Silorane system adhesive self-etch primer was applied to the enamel and dentin surfaces. After waiting for 20 seconds, the excess solvent was evaporated with a gentle blast of air for 10 seconds, and the primer was light cured for 10 seconds. Bond was applied to all surfaces and light cured for 10 seconds.

One flat 1.5-mm-thick composite resin increment was used to restore the cavity. Prior to light curing, one diagonal cut was made in this increment using a plastic filling instrument with a blunt blade to split it into two triangular-shaped flat portions. The resulting two portions were light cured for 40 seconds. The diagonal cut was first half filled with the composite and light cured for 20 seconds. Following this, the remaining half of the diagonal cut was filled with resin composite and cured for 20 seconds.

Group II: Oblique incremental technique with silorane composite

Following the same procedures applied in group I, an oblique incremental technique was used for this group. The resin material was inserted into the cavity using an oblique incremental technique. Due to the limited depth of cavity, the number of oblique layers was limited to two oblique layers of 1.5 mm each. [11] Each incremental layer was cured for 20 seconds.

The specimens were stored at 100% relative humidity at 37°C for 24 hours and were then submitted to 1000 thermal cycles at 5°C and 55°C with a dwell time of 1 minute at each temperature. The specimens were then covered with two layers of nail varnish, except the resin composite restoration and 1 mm area around it, followed by immersion in 0.6% aqueous rhodamine dye for 48 hours. The specimens were rinsed and sectioned buccolingually through the center of restorations with a slow speed diamond disk. The specimens were polished using alumina paste in decreasing order of granulation, followed by an ultrasonic bath.

Microleakage was measured using confocal microscopy at 10× magnification (Confocal Fluorescence Imaging Microscope, Leica TCS-SP5, DM6000-CFS) and in the fluorescent mode. Approximately, six photographs of each specimen were taken to obtain the full perimeter of the restoration. With a digital scale (Snagit digital scale), the width of interface between restoration and tooth surface was calculated.

The microleakage score was also recorded using the scoring method, as per Alavi and Kianimanesh.[12] The scores are as follows.

No dye penetration.

Dye penetration within one-half of occlusal or gingival wall.

Dye penetration extending to the end of occlusal or gingival walls.

Dye penetration through the gingival or occlusal wall to one-third of axial wall.

Dye penetration through the gingival or occlusal wall to two-thirds of axial wall.

Dye penetration throughout the axial wall

The results were subjected to statistical analysis by using paired “t” test and Mann–Whitney analysis.

RESULTS

When scores were analyzed, no difference was found between the two layering techniques.

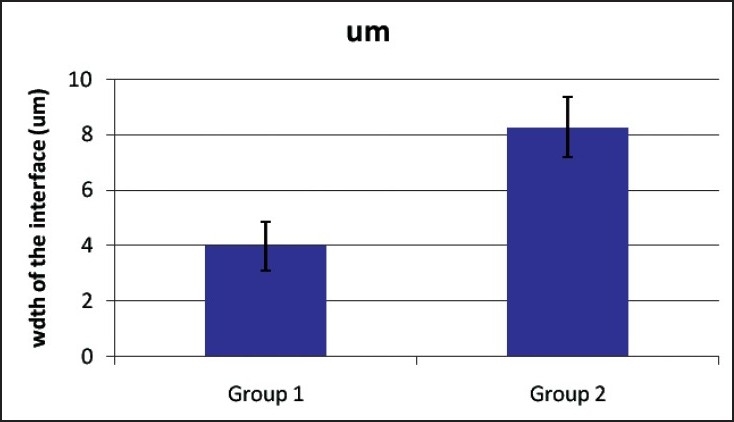

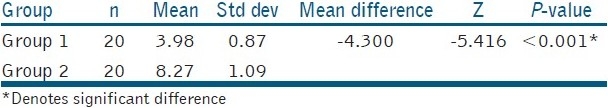

Microleakage was seen along the entire perimeter of restoration, irrespective of the layering technique used [Table 1]. Graph depicting mean width of the interface, as measured by confocal microscopy in different layering techniques has been shown [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Microleakage score evaluated in two different techniques

Figure 1.

Mean width of the interface, as measured by confocal microscopy in different layering techniques.

Microleakage in specimens restored with split incremental technique and oblique layering technique, visualized by confocal microscopy.

The width of interface in restorations prepared with split incremental technique was significantly lesser than the one restored with oblique layering technique, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of width of interface in specimens restored with two layering techniques by using the Mann–Whitney test

DISCUSSION

Resin–dentin interface sealing is a desirable property of dentin bonding system in preventing the pulp–dentin complex from being exposed to bacteria and their toxins.[13] Polymerization stresses developed at the adhesive interface play an important role in the marginal adaptation of resin composite restorations. Contraction stress values can exceed the bond strength, leading to the formation of openings and gaps. They are considered deleterious because they allow the transfer of fluid between the oral environment and the pulp through the dentin tubules. Control of such stresses improves the bond strength and marginal seal of composite resin to dentin.[14]

Different incremental layering techniques,[15,16] C factor analysis,[17] low shrink materials[18,19] and a combination of different restorative materials[20] have been used in efforts to prevent this problem.

One approach to minimize the effects of curing shrinkage is the insertion of resin composite in increments, which lowers the configuration factor. The configuration factor (C factor) is the ratio between the bonded and free surfaces of the cavity. High C factor can cause adhesion breakdown between the restorative system and the cavity wall.[21] The use of incremental techniques has been extensively studied. Moezyzadeh and Kazemipoor found that oblique (gingivo-occlusal) technique showed less microleakage in gingival margins of the restorations compared to bulk technique.[7] In the present study, the authors used oblique and split incremental techniques that have lower C factor values to reduce shrinkage stress in class V cavities.

The width of interface at the resin–dentin junction was used as a parameter to assess the polymerization shrinkage occurring at resin–dentin interface, as the width is directly proportional to the amount of resin polymerization. In the current study, the width of interface was significantly less with split incremental technique.

In the split incremental technique, one 1.5-mm-thick flat increment was used. The actual number of increments needed depends on the volume of space undergoing restoration, with larger lesions requiring more incremental applications of composite resin. Relief of such stresses was achieved through the use of diagonal cut to split each flat increment into two triangular-shaped portions before light curing. The free, unbonded composite surfaces created by the diagonal cut would convert the restricted shrinkage occurring on the cavity walls prior to splitting to unrestricted shrinkage.

This serves as a reservoir for flow or plastic deformation in the initial stage of polymerization.[11] In the present study, the authors made only one diagonal cut, as the volume of the cavity to be restored was less.

Composite filling and light curing of 1.5-mm-wide diagonal cuts in each increment were performed; so, one diagonal cut was completely filled and light cured, followed by filling and curing of one-half of the second diagonal cut at a time. This sequence would prevent composite resin from connecting two opposing cavity walls at the same time, thereby minimizing the development of the detrimental polymerization shrinkage stresses on adhesive interfaces at cavity walls and margins.[11]

Since the type of composite and bonding system can influence the amount of polymerization shrinkage and the resulting microleakage, silorane-based resin composite (Filtek™ P90 Silorane Low Shrink Restorative, 3M ESPE) was used as a restorative material in our study. Palin and others[19] used experimental silorane and an experimental silorane bonding system in their study. All tested mesioocclusodistal restorations exhibited microleakage in the Palin study, but the microleakage of experimental silorane-based composite restorations was lesser than commercial methacrylate-based composite restorations. Bagis et al.[4] showed that the silorane-based microhybrid resin composite system had no microleakage for wide class II MOD restorations with oblique and vertical layering techniques. The present study showed that microleakage was present in both the groups, but significantly reduced with split incremental technique. These contrary results may be attributed to the methodology used in the techniques. Bagis et al. used in their study stereomicroscope at ×10 magnification. In the present study, CLSM was used to assess the extent of microleakage, which is considered to be a more reliable tool.

The present study measured microleakage using confocal microscopy at low magnification (×10), differing from other microleakage studies. CLSM is a nondestructive technique for visualizing subsurface tissue features. One of its advantages is the clear indication of leakage limits, due to a lens focus that can occur some microns beneath the observed surface. This eliminates the stain spread caused by specimen sectioning and also avoids polishing artifacts that exaggerate dye penetration.

Subsequent observation of CLSM is made possible by elimination of scattered, reflected and fluorescent light from planes other than the plane from which the image is created, the focal plane.[22] The laser scanning microscope scans the sample sequentially point by point and line by line and assembles the pixel information into one image.[9]

The main problem and important limitation of microleakage studies is that microleakage only reveals a minor aspect of adhesion.[9] In the present study, all the experimental groups showed extensive leakage and, although significant differences were found among them, the clinical relevance of these differences remains questionable.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the limitations of this study, it may be concluded that in class V restorations, microleakage is observed regardless of the technique used and Split incremental technique shows lesser microleakage than the oblique layering technique.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff members of Imaging Centre, Indian Institute Of Science, Bangalore, Mr. Sanjay Prasad and Ms. Pushpa J., for their support in this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stavridakis MM, Krejci I, Magne P. Immediate dentin sealing of onlay preparations: Thickness of pre-cured Dentin Bonding Agent and effect of surface cleaning. Oper Dent. 2005;6:747–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadowsky SJ. An overview of treatment considerations for esthetic restorations: A review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson CL, Feilzer AJ. Polymerization shrinkage and polymerization shrinkage stress in polymer-based restoratives. J Dent. 1997;25:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagis YH, Baltacioglu IH, Kahyaogullari S. Comparing microleakage and the layering methods of silorane-based resin composite in wide class II MOD cavities. Oper Dent. 2009;34:578–85. doi: 10.2341/08-073-LR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd E, Beighton D. Prediction of secondary caries around tooth-colored restorations: A clinical and micrbiological study. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1942–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750120501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Going RE. Microleakage around dental restorations: A summarizing review. J Am Dent Assoc. 1972;84:1349–57. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1972.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moezyzadeh M, Kazemipoor M. Effect of Different Placement Techniques on Microleakage of Class V Composite Restorations.Tehran University of Medical Sciences. J Dent. 2009;6:3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crim GA. Microleakage of three resin placement techniques. Am J Dent. 1991;4:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes MB, Consani S, Gonini-Junior A, Moura SK, McCabe JF. Comparision of microleakage in human and bovine substrates using confocal microscopy. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2009;50:111–6. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.50.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajami B, Makarem A, Niknejadc E. Microleakage of Class V Compomer and Light-Cured Glass Ionomer Restorations in Young Premolar Teeth. Journal of Mashhad Dental School, 2007;31(Special issue):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan KA, Khier SE. Split-increment Technique: An Alternative Approach for Large Cervical Composite Resin Restorations. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavi AA, Kianimanesh N. Microleakage of direct and indirect composite restorations with three dentin bonding agents. Oper Dent. 2002;27:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perdiagao J, Lambrechts P, Meerbeek VB, Breaem M, Yildiz E, Yucel T, et al. The Interaction of Adhesives Systems With Human Dentin. Am J Dent. 1996;9:167–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho RM, Pereira JC, Yoshiyama M, Pashley DH. A Review of Polymerization Contraction: The Influence of Stress Development Versus Stress Relief. Oper Dent. 1996;21:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coli P, Brannstrom M. The marginal adaptation of four different bonding agents in class II composite rein restorations applied in bulk or two increments. Quintessence Int. 1993;4:583–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aranha AC, Pimento LA. Effect of two different restorative techniques using resin based composites on microleakage. Am J Dent. 2004;17:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giachetti L, Scaminaci RD, Bambi C, Grandini R. A review of polymerization shrinkage stress: Current techniques for posterior direct resin restorations. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;17:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamazaki PC, Bedran-Russo AK, Pereira PN, Swift EJ. Microleakage evaluation of a new low shrinkage composite restorative material. Oper Dent. 2006;31:670–6. doi: 10.2341/05-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palin WM, Fleming GJ, Nathwani H, Burke FJ, Randa RC. In vitro cuspal deflection and microleakage in maxillary premolars restored with novel low-shrink dental composites. Dent Mater. 2005;21:324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beznos C. Microleakage at the cervical margin of composite Class II cavities with different restorative techniques. Oper Dent. 2001;26:60–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feilzer AJ, Gee DA, Davidson CL. Quantitative determination of stress reduction by flow in composite restorations. Dent Mater. 2005;6:167–71. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(90)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minsky M. Memoir on inventing the confocal scanning microscope. J Scanning. 1988;10:128–38. [Google Scholar]