Abstract

The objective of this paper is to provide a systematic review on the epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in India based on the data published from 1960 to 2009. Extensive search of PubMed, NeuroMed, Indian Journal of Psychiatry website and MEDLARS using search terms “psychiatry” “prevalence”, “community”, and “epidemiology” was done along with the manual search of journals and cross-references. Retrieved articles were systematically selected using specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Epidemiological studies report prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders varying from 9.5 to 370/1000 population in India. These varying prevalence rates of mental disorders are not only specific to Indian studies but are also seen in international studies. Despite variations in the design of studies, available data from the Indian studies suggests that about 20% of the adult population in the community is affected with one or the other psychiatric disorder. Mental healthcare priorities need to be shifted from psychotic disorders to common mental disorders and from mental hospitals to primary health centers. Increase in invisible mental problems such as suicidal attempts, aggression and violence, widespread use of substances, increasing marital discord and divorce rates emphasize on the need to prioritize and make a paradigm shift in the strategies to promote and provide appropriate mental health services in the community. Future epidemiological research need to focus on the general population from longitudinal prospective involving multi-centers with assessment of disability, co-morbidity, functioning, family burden and quality of life.

Keywords: Psychiatric Epidemiology, Community, Prevalence, Research

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of mental illness frequency in human beings, with the fundamental aim of understanding and controlling the occurrence of mental illness. Psychiatric epidemiology deals with important components such as disease/disorder, distribution and frequency of disease/disorder, determinants of disease/disorder, human population and methods employed to control the occurrence of illness.[1]

Mental disorders constitute a wide spectrum ranging from sub-clinical states to very severe forms of disorders. Mental health problems can attain the disorder/disease/syndrome level, which are usually considered easy to recognize, define, diagnose and treat. Hence, they can be called, ‘Visible Mental Health Problems’ in a community. These visible mental health problems are again classified into Major mental disorders and Minor mental disorders. Major mental disorders are easy to recognize and commonly seen in mental hospitals, however, minor mental disorders are common in the community. Another group of mental health problems remains at the sub-clinical/non-clinical/sub-syndromal level and are usually related to the behavior of an individual. They are difficult to recognize, define and diagnose. Hence, they are called, ‘Invisible Mental Health Problems’. Psychiatric epidemiological studies have ignored this category because of the difficulty in defining and identifying the case. It has also been argued by many researchers, not to pathologize the problems faced by the individuals.

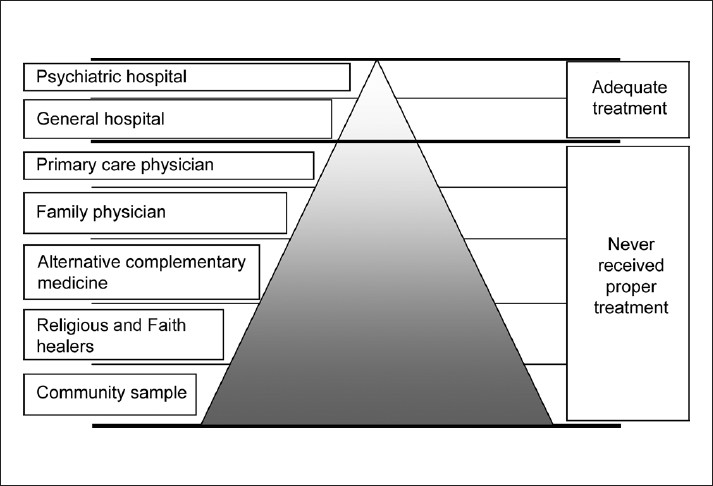

Popular approaches to measure the disease frequency in a given population are, (i) hospital catchment population approach and (ii) community survey.[2] Hospital-based approach counts the number of cases diagnosed by a clinician (as numerator) and the catchment population served by the hospital facilities (as denominator). The generalizability of the findings of these hospital studies to the community setting is very difficult, especially in developing countries because of the following reasons: a) hospital samples generally comprise severely ill patients, b) patients may approach the hospital far away from home (not the nearest treatment center) due to stigma and discrimination and c) disease variants seen in the community may be with mild impairment. This can be explained by the pathways to care pyramid as shown in Figure 1. At the bottom of the pyramid remains a huge population of mentally ill patients who may not receive treatment at all. Hence, to get the true picture, community sampling is advocated.

Figure 1.

Pathways to mental health care pyramid in developing countries

Psychiatric epidemiology lags behind other branches of epidemiology due to difficulties encountered in conceptualizing, defining a case and diagnosing, sampling technique, lack of trained manpower, poor knowledge, data collection from a single informant, systematic under - reporting, stigma, lack of adequate funding and low priority of mental health in the health policy.[3–4] In spite of the above challenges there have been endeavors into descriptive psychiatric epidemiological studies, but advances with respect to cost-effective, analytical and prospective experimental epidemiological studies have been minimal.

Descriptive epidemiological studies have provided data about the prevalence of mental disorders in the community. However, many researchers have expressed reservations about the comparison of various epidemiological studies because of methodological differences. Varying prevalence rates have been reported in international studies like the Epidemiological Catchment Area Program and the National Comorbidity Survey.[5–6] Above all this, psychiatric disorders are known to vary across time within the same population and also vary across populations at the same time. This dynamic nature of the psychiatric illnesses will impact planning, funding and healthcare delivery. Providing accurate data about the prevalence of mental disorders is essential in policy-making. Hence this chapter attempts to critically evaluate the (overall) prevalence rate of psychiatric disorders as reported in epidemiological studies from India. In addition, it also attempts to address the following questions, a) What is the accurate prevalence of psychiatric disorders? b) Is the prevalence of psychiatric disorders reported in India similar to other international studies? c) Is the prevalence rate of psychiatric disorders stable or changing? d) Are there any population subgroups which are at a high risk of developing mental illness? e) What is the cost of treating psychiatric patients? and f) What should be the focus for future epidemiological studies?

Methodology of the review

Extensive search was done on Neuromed (1982-1997), Pubmed, Indian Journal of Psychiatry website and MEDLAR for published Indian psychiatric epidemiological studies between 1960 and 2009. The search terms included, “Psychiatry” “Prevalence”, “Community”, and “Epidemiology”. Attempts were also made to retrieve Indian epidemiological studies published in international journals through Pubmed using the search terms, “psychiatry” and “epidemiology”. Extensive manual search of earlier and later issues of the Indian Journal of Psychiatry, NIMHANS Journal and ICMR journals was also done. Cross-references of the psychiatric prevalence studies were also reviewed by the authors.

Studies selected for the review were: General population studies, either urban, rural or mixed from India; community study design involving door-to-door/house-to-house enquiry of families and random sampling of families and inclusion of all psychiatric disorders or at least priority/major mental disorders (various researchers have used this term to assess schizophrenia, manic depressive psychosis, organic psychosis, epilepsy and mental retardation in the community). Studies were excluded if those were: Specific syndrome/illness/disorder studies and hospital or clinic-based studies. Only published data was considered due to logistic reasons. This is one of the main limitations of this review. Only 16 prevalence studies [Table 1] fulfilled the above cited criteria. However, the authors also made an attempt to summarize other studies like high-risk/special population, cost-effective analysis, incidence, follow-up and meta-analysis separately to have a comprehensive picture of epidemiological studies.

Table 1.

Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the general population

| Investigator | Year | Center | Location | Sampling | Tool | Population | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surya[8] | 1964 | Pondicherry | U | H-H | MHSQ(P) | 2731 | 9.5 |

| Sethi et al.[9] | 1967 | Lucknow | U | H-H | QAPF | 1733 | 72.7 |

| Dube[10] | 1970 | Agra | M | H-H | DCP | 29.468 | 18 |

| Elnager et al.[11] | 1971 | Hoogly | R | H-H | CHM and DCP(2) | 1393 | 27 |

| Sethi et al.[12] | 1972 | Lucknow | R | H-H | CHQ and CHM | 2691 | 39.4 |

| Verghese et al.[13] | 1973 | Vellore | U | SRS | MHIS and DCP as per ICD (1965) | 1887 | 66.5 |

| Sethi et al.[14] | 1974 | Lucknow | R | 3SPS | PSQ and DCP as per DSM-II (1968) | 4481 | 67.0 |

| Thacore et al.[15] | 1975 | Lucknow | U | H-H | PHQ and DCP | 1977 | 81.6 |

| Nandi et al.[16] | 1975 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, QS and CRS as per ICD (1965 R) | 1060 | 102.8 |

| Nandi et al.[17] | 1979 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 3718 | 102 |

| Shah et al.[18] | 1980 | Ahmedabad | U | H-H | MHSQ and DCP | 2712 | 47.2 |

| Mehta et al.[19] | 1985 | Vellore | R | S-S | IPSS and DCP | 5941 | 14.5 |

| Sachdeva et al.[20] | 1986 | Faridkot | R | H-H | HS, SESS and CDS | 1989 | 22.12 |

| Premrajan et al.[21] | 1993 | Pondichery | U | RS | IPSS and DCP as per ICD-9R | 1115 | 99.4 |

| Shaji et al.[22] | 1995 | Erankulam | R | H-H | IPSS, SESS, CRS and DCP, ICD-10 | 5284 | 14.57 |

| Sharma and Singh[23] | 2001 | Goa | M | SRS | RPES and DCP as per ICD-9 | 4022 | 60.2 |

Source: Math et al. 2007, IJMR, 183-192

Abbreviation - U - urban; R - rural; H-H - house to house survey; S-S.- systematic sampling; SRS - stratified random sampling 3SPS - 3-stage probability sampling; RS - random sampling, ICD - international classification of diseases DSM-II - diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Tools: MHSQ = Mental health screening questionnaire; QAPF = Questionnaire for the assessment of psychiatric state of the family; DCP = Diagnosis confirmed by a psychiatrist(s); CHM = Case history method; CHQ = Case history questionnaire; IPSS = Indian Psychiatric survey schedule; SFQ = Social functioning questionnaire; MHIS = Mental health item sheet; PSQ = Psychiatric screening questionnaire; PHQ = Psychiatric health questionnaire; HS = Household schedule; QS = Questionnaire schedule; CRS = Case record schedule; CDS = Case detection schedule; SESS = Socioeconomic status schedule; RPES = Rapid psychiatric examination schedule

What is the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in India?

Prevalence can be simply defined as total number of persons in the population who have a psychiatric disorder at a point or period in time. It refers to both old (existing) and new (occurring) cases. In the above definition, if the observational period is at a given point in time it is called as ‘point prevalence’ and if it is at a given specific period in time it is called as ‘period prevalence’.[7]

Most of the community-based Indian epidemiological studies are on point prevalence. Table 1 summarizes the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the general population. These community-based epidemiological studies conducted in India on mental and behavioral disorders report varying prevalence rates, ranging from 9.5[8] to 102[16] per 1000 population.

What are the reasons for wide variations in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders?

Prevalence rate of mental disorders vary within a population over a period of time and also across populations at the same time. This dynamic nature of mental disorders may play a role in the varying rates reported in Indian epidemiological studies. Similarly, on plotting the psychiatric epidemiological studies on the Indian map, studies are found to be concentrated only in certain places like [approximately] West Bengal (40%) and Uttar Pradesh (10%), which leads to difficulty in generalizing the findings.[3]

Defining a case is also one of the factors which contributed to the huge variation in the prevalence rate. If the threshold for defining a case is very low then the prevalence rate will be very high.[24–25] Mental disorders are highly stigmatized conditions that many people want to keep private because of embarrassment or fear of discrimination.[26] The problem of systematic under - reporting continues to be a major challenge for the future of psychiatric epidemiology in India. For example, a survey of an urban community in southern India found that one-third of people with schizophrenia had never accessed any treatment resources.[27] Even after the diseased individuals and their families were offered treatment, a third of them remained untreated.[28] In Indian epidemiological studies, many researchers interviewed only the head of the family or the housewife or any other responsible family member for data collection. This will lead to responder bias and also recall bias. There is a high chance of underreporting of symptoms of minor mental disorders [Table 2].[3]

Table 2.

Reasons for wide variations reported in Indian epidemiological studies

|

All the above factors played a crucial role in underreporting the prevalence rate in most of the Indian epidemiological studies. Because the screening instrument applied to the entire population had poor sensitivity in identifying minor mental disorders and also in high-risk populations such as the children and the elderly, it resulted in missing minor mental disorders during the initial screening. However, the majority of the researchers confirmed the diagnoses that were identified through the screening in the second phase avoiding false. positive cases. In addition to the poor screening instrument, recall bias, single informant and systematic underreporting have led to underreporting of mental disorders rather than over-reporting in Indian epidemiological studies

Though the majority of the epidemiological studies considered two-phase sampling for assessing prevalence,[8,10,14,15,18] they were unable to tap the non-psychotic disorders like panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, adjustment disorder, dissociative disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, sexual dysfunctions, substance use and so forth in the community. Earlier studies prepared their own screening questionnaires, which was applied to the entire population to be studied without testing their validity for high-risk populations such as children, elderly and substance users, resulting in missing out on the minor mental disorders during the initial screening.[8,11,14,15] This was a major drawback of these studies, which may have led to underreporting of mental disorders.

The sampling procedure employed should be appropriate, such that the sample obtained should be representative of the general population. If this is not achieved then the generalizability of the findings becomes difficult. Studies done on high-risk populations yielded a high prevalence rate. Hence, the selection should be representative of the general population. In the design of studies of people with mental disorders, in a community survey, it is also necessary to consider the likelihood of not being able to access people who are hospitalized due to illness, homeless people, wandering mentally ill patients and people who are not available for other reasons like occupation, custodial care, continuous care facilities and hospitalization for chronic physical illness.[29]

What is the accurate prevalence of psychiatric disorders?

Policymakers are haunted by major discrepancies in the prevalence of mental disorders. Unfortunately, there is no sharp boundary between mental disorders and normalcy. Weak agreement at the level of diagnosis continues to threaten the credibility of estimates of prevalence.[30] However, efforts to overcome these discrepancies through meta-analysis and adding prevalence of individual disorders helped give meaning to the data, thereby enabling policy makers to plan service delivery.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis of 13 epidemiological studies consisting of 33,572 persons, who met the following criteria: Door to door survey, all age groups included and prevalence rate for urban and rural being available,[31] reported a total morbidity of 58.2 per 1000. Though meta-analysis has its own limitations, this was the first attempt to analyze the epidemiological studies. Another meta-analysis of epidemiological studies reported a total morbidity of 73 per 1000.[32] The difference noted in the two available meta-analyses is due to the methodology of selecting the papers for the review [Table 3].

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of Indian epidemiological studies

| Investigator | Year | Population | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reddy and Chandrasekar[31] | 1998 | 33,572 | 58.2 |

| Ganguli[32] | 2000 | - | 73 |

Source: Math et al., 2007, IJMR, 183-192

Macro-economic commission report

Macro-economic commission report of 2005[33] considered prevalence rate of 65/1000 population (average of two meta-analyses) and projected the prevalence rate for the next two decades [for more details please see the report of NCMH Background Papers - Burden of Disease in India[33]].

Modest estimation of Psychiatric Morbidity

If we consider the prevalence of individual mental disorder and add, then the overall prevalence rate is approximately 190-200/1000 population [Table 4]. In simple words, at least 20% of the population does have one or the other mental health problem, which requires intervention from a mental health professional. This estimate has been developed based on secondary data from available sources along with an in-depth review of existing databases in the Indian region. Only core psychiatric disorders have been addressed in this estimate. Considering the fact of systematic underreporting, collecting data from single informant, use of low-sensitivity screening instruments and assessing only priority mental disorders, the prevalence of mental disorders reported in Indian epidemiological surveys can be considered lower estimates rather than accurate reflections of the true prevalence in the population.[3]

Table 4.

Modest estimate of the mental health morbidity

| Mental Disorders | Prevalence/1000 | % | Total population in crores* | Mental morbidity in lakhs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (including organic) | 5-10 | 1 | 108 | 108 |

| Mood disorders | 15-30 | 3 | 324 | |

| Cannabis users | 5-10 | 1 | 108 | |

| Opiate users | 1-3 | 0.3 | 32 | |

| Mental retardation | 5-6 | 0.6 | 65 | |

| Dementia | 2-5 | 0.5 | 54 | |

| Common mental disorders | 20-30 | 3 | 324 | |

| Alcohol dependence syndrome | 30-40 | 4 | 432 | |

| Child and adolescent disorders | 110-120 | 12 | 40 | 480 |

| Geriatric disorders | 25-30 | 3 | 8 | 24 |

| 1951 |

As per census 2001 above table does not include the following psychiatric morbidities: One-third of the patients suffering from any chronic medical conditions (such as Diabetes, Hypertension, Cancer, Asthma, Ischemic heart diseases, Arthritis, HIV, Psoriasis, Chronic renal failure, Cerebro-Vascular accidents, Epilepsy, Auto-immune disorders, Obesity, infertility and so forth) also have co-morbid diagnosable psychiatric disorders, which are usually not diagnosed and never treated. Similarly, one-third of the patients attending the outpatient section of any primary health center or general hospitals suffer from diagnosable psychiatric disorders such as psychosomatic disorders, somato form disorders, medically unexplained symptoms, depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, premenstrual syndrome and so forth

Is the prevalence of psychiatric disorders reported in India similar to other international studies?

Comparison with International studies

NIMH-Epidemiological Catchment Area study[34] of the US reported psychiatric morbidity as follows; one year incidence of 60/1000 population, one month prevalence of 151/1000 population and lifetime prevalence of 322/1000 population. National Co-morbidity Study of the US[35] reported 12 months prevalence of 277/1000 population and lifetime prevalence of 487/1000 population. On comparing the Indian epidemiological studies to any international epidemiological studies, it is found that prevalence rates reported in India are very low. Possible reasons for this difference have been discussed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Low prevalence of psychiatric disorders in India can be attributed to the following reasons

| Indian epidemiological studies were not able to measure psychiatric morbidity adequately |

| Psychiatric prevalence rates are truly low in India because of |

| Genetic reasons, |

| Good family support, |

| Social support, |

| Cultural Factors |

| Lifestyle |

| Better coping skills and comfortable environment |

| Combination of above factors |

Available evidence supports the first possibility of the underreporting by Indian epidemiological studies. However, the remote possibility of genuine low prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the Indian population cannot be disregarded because of low rates of substance use in the general population compared to Western countries and good outcome of psychiatric disorders due to various factors like better coping skills, religious, cultural, social and family support.

Is the prevalence rate of psychiatric disorders stable or changing?

Does globalization and recession play a role in the mental health of individuals? Does changing family structure (joint family to nuclear) influence psychiatric morbidity? Unfortunately, we don’t have any long-term epidemiological studies to answer these questions.

Follow-up studies

A 10-year follow-up study reported that there was not much change in the prevalence rates over a decade.[36] This was further reinforced by the 20-year follow-up study.[37] These two studies [Table 6] are milestones in psychiatric epidemiology that focus on the same population cross-sectionally at two points. Though the prevalence rate did not change, the morbidity pattern changed significantly. However, researchers and policymakers should exercise caution before generalizing the findings to the entire country. Reason being, follow-up studies had a small sample size and were done in a rural population. Researchers should also consider the changing trend in the Indian population before generalizing the findings.

Table 6.

Follow-up studies on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in India

| Investigator | Year | Center | Location | Sampling | Tool | Year | Population | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nandi et al.[36] (1972-1982) | 1986 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 1972 | 1060 | 84.9 |

| 1982 | 1539 | 81.9 | ||||||

| Nandi et al.[37] (1972-1992) | 2000 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS, CRS and DCP | 1972 | 2183 | 116.8 |

| 1992 | 3488 | 105.2 |

As given in the footnote of Table 1; Source: Math et al., 2007, IJMR, 183-192

Incidence studies

There are only two incidence studies [Table 7] conducted in India,[38–39] there is a need to carry out more incidence studies in representative populations. Incidence studies are essential to know the impact of intervention programs, globalization, recession, disaster and so forth.

Table 7.

Incidence studies done in India

| Investigator | Year | Center | Location | Sampling | Tool | Year | Population | Prevalence/1000 | Incidence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nandi et al.[38] (1972-1973) | 1976 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, QS and CDS | 1972 | 1060 | 102.1 | 17.6 |

| 1973 | 1078 | 107.6 | |||||||

| Nandi et al.[39] (1972-1973) | 1978 | West Bengal | R | H-H | HS, CDS and CRS | 1972 | 2230 | 110.3 | 16 |

| 1973 | 2250 | 108.4 |

As given in the footnote of Table 1; Source: Math et al., 2007, IJMR, 183-192

Though there are no systematic studies in answering the above questions. However, an increase in population has definitely increased the number of mentally ill patients in India. Lack of mental health manpower is a major threat to developing comprehensive psychiatric services in the community. In spite of best efforts, the ratio between psychiatrist and population is worsening day-by-day. Main reason being, the Indian population is growing at a rapid speed while the development of manpower is not. There are no attempts to address the issue of manpower in the area of mental health.

Are there any population subgroups which are at high risk of developing mental illness?

Various studies have clearly shown that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders is high in certain population. Population at high risk of develop psychiatric disorders are depicted in Table 8.

Table 8.

Population at high risk of develop psychiatric disorders are as follows

| Female gender |

| Child and adolescent population |

| Students |

| Geriatric population |

| People suffering from chronic medical conditions |

| Disabled population |

| Disaster survivors |

| Population in custodial care |

| Marginalized population |

| Refugees and individuals with poor family, social and economical support |

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in child and adolescent population studies

Children and adolescents are at high risk of developing mental disorders. The majority of available Indian general population prevalence surveys [Table 1] have not utilized specific tools for addressing the disorders in children and adolescents. They have formulated their own screening instruments or they have utilized screening instruments which can be applied to the adult population, hence no doubt they have missed out mental morbidity in children and adolescents. A review article by Bhola and Kapur[40] has summarized the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the child and adolescent population. They have reviewed both community and also school-based population studies. Early studies reported prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders among children ranging from 13 to 94 per 1000.[16,41–42]

There are only a few epidemiological studies which were exclusively conducted to assess the prevalence rate in the child and adolescent population. The first methodologically superior study reported a prevalence rate of 94 per 1000 in a sample of 1403 rural children aged 8-12 years.[43] Another methodologically strong ICMR-sponsored study conducted by Srinath and colleagues in 2005, has reported a prevalence rate of 12.5% among children aged 0-16 years.[44] Similarly, a recent study also reported a prevalence rate of 16.5% in children 6-14 years of age.[45] Table 9 summarizes the prevalence rate of the child and adolescent population. Since children and adolescent form 40% of the total population of India,[46] approximately four crores of the population require professional help.

Table 9.

Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in child and adolescent population studies

| Investigator | Year | Center | Age (yrs) | Location | Sampling | Tools | Population | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sethi et al.[9] | 1967 | Lucknow | 0-10 | U | H-H | IQ, ICD-7 | 541 | 94 |

| Dube et al.[10] | 1971 | Agra | 5-14 | M | H-H | DCP | 8035 | 11.67 |

| Elnagar et al.[11] | 1971 | Hoogly | 0-15 | R | H-H | CHM and DCP(2) | 635 | 13 |

| Sethi et al.[12] | 1972 | Lucknow | 0-10 | R | H-H | IQ, ICD-7 | 877 | 81 |

| Varghese et al.[42] | 1974 | Vellore | 4-12 | U | SRS | MHIS and DCP as ICD (1965) | 747 | 81.7 |

| Nandi[16] | 1975 | Kolkata | 0-11 | R | H-H | IQ, DCP as per ICD (1965) | 462 | 26 |

| Hackett et al.[43] | 1999 | Kerala | 8-12 | U | RCS | CBQ, ICD-10 | 1403 | 94 |

| Srinath et al.[44] | 2005 | Bangalore | 0-16 | U | SMS | SDP, SCL, CBCL, CBQ, FTN, DISC, PIS, VSMS, BKT, CGAS | 2000 | 124 |

| Anita et al.[45] | 2007 | Rohtak | 6-14 | M | SRS | CPMS and DISC | 800 | 165 |

U - urban; R - rural; M - Mixed; H-H - house to house survey; RCS - Random cluster sampling; SRS - stratified random sampling; SMS - stratified multistage sampling; ICD - international classification of diseases; Tools - IQ - Interview questionnaire; CHM - Case history method; DCP - Diagnosis confirmed by a psychiatrist(s); MHIS - Mental health item sheet; CBQ - Child behavior questionnaire; SCL - Screening checklist; SDP - Socio demographic proforma; CBCL - Child Behavior; Checklist PIS - Parent interview schedule; BKT - Bitnet karat test; VSMS - Vineland social maturity scale; FTN - Felt treatment needs CGAS - Children�s global assessment scale; DISC - Diagnostic interview schedule for children; CPMS - Childhood Psychopathology Measurement Schedule

Geriatric population

Senior citizens are at a high risk of developing mental disorders. The geriatric population, aged 60 years and above, forms nearly 7.5% of the total population of India.[46] A study conducted in two villages of West Bengal reported that 61% of the geriatric population needed psychiatric help.[47] Majority of them were suffering from depression. Other commonly reported mental disorders are insomnia, sexual dysfunction, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, organic mental disorders and dementia. Depression is a common cause of disability in the elderly. Consequences of untreated depression are, reduced life satisfaction and quality, social deprivation, loneliness, increased use of medications and health services, insomnia, cognitive decline, suicide and increased mortality. There is a definite need for conducting systematic studies in the geriatric population to estimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Disaster and mental health

Disasters are potentially traumatic events which impose ‘massive collective stress’ consequent to ‘violent encounters with nature, technology or mankind’.[48] Disasters threaten personal safety, overwhelm defense mechanisms, and disrupt community and family structures. They may also cause mass casualties, destruction of property, and lead to a collapse of the social networks and daily routines.[49] A typical pattern of mental, emotional, and physical response is observed in the majority of people after exposure to any disaster.[50] Various international studies have reported a wide range from 30-70% of mental health morbidity as an immediate aftermath of a disaster. A meta-analysis of 160 international studies of disaster victims found that posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorders and panic disorder, were commonly identified by most of the studies.[51] The disaster mental health branch lags behind in terms of coordination, training, services, research and evidenced-based practices in India.

Other high-risk populations

In Indian epidemiological studies researchers have sampled special population groups [Table 10] like urban slum dwellers,[52] uprooted communities,[53] urbanized tribal communities[54–55] and attempted to compare across cultures.[56–57] Studies done on the high-risk population yielded high prevalence rates.[24]

Table 10.

Special/high-risk population studies

| Investigator group | Year Center | Nature of risk | Location | Sampling | Tool | Population | Prevalence/1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carstairs and Kapur[24] | 1973 | Social changes in the community | R | H-H | IPSS and SFQ | 1233 | 370 |

| Nandi et al.[56] | 1977 | Tribal community | R | H-H | HS, QS and CDS | 2918 | 58.2 |

| Nandi et al.[53] | 1978 | Uprooted community | R | H-H | HS, QS and CDS | 1259 | 47.6 |

| Nandi et al.[57] | 1980 | Marginalized population | R | RS | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 4053 | 50.3 |

| Nandi et al.[58] | 1980 | Urbanization | M | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 1862 | 129.9 |

| Sen et al.[52] | 1984 | Urban slum dwellers | U | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 2168 | 48.7 |

| Banerjee et al.[54] | 1986 | Urbanized tribal community | U | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 771 | 51.9 |

| Nandi et al.[55] | 1992 | Urbanized tribal community | U | H-H | HS, SESS, CDS and CRS | 1424 | 47.75 |

As given in the footnote of Table I Source: Math et al., 2007, IJMR, 183-192

What is the economic cost of treating psychiatric patients?

Prevalence of mental illness is approximately 200/1000 population [Table 4]. In simple words, approximately 20 crores of the population require professional help. Each mentally ill patient requires Rs. 500 per month for mental healthcare [Table 11]. This includes medication cost, doctor’s fees and travelling cost to meet the doctor. Then the approximate total cost required per month will be Rs.10,000 crores. Unfortunately, mental illness requires medication for longer duration. Most of them require medications ranging from several months to years. Many of these disorders if not detected early and treated, may become chronic and require medication for life. If we don’t address this issue, then the indirect costs in terms of loss of wages, disability, absenteeism and substance use is unimaginable. Above all these families encounter social isolation, burden, stigma, poor quality of life and enormous psychological strain.

Table 11.

Cost of treating mentally ill patients

| Per month (Rs.) | |

|---|---|

| Cost for mental healthcare for an individual | |

| Medication cost per month for an individual suffering from mental illness | 300 |

| Traveling cost to meet the mental health professionals | 100 |

| Doctors fees (mental health professionals) | 100 |

| Total | 500 |

| Cost for mental healthcare for the whole country | |

| If we consider the psychiatric prevalence as 200/1000 population (see table 4), then 20 crores of the population require professional help. (Prevalence is 20 crore population X Cost per month per patient is 500 Rs) | 10,000 crores |

Is there a need to fund psychiatric epidemiological studies?

The new generation of mental health surveys required at this point of time are to determine the quality of life, co-morbidity, disability and burden of various mental disorders.[59] There is a need for longitudinal/prospective (experimental) epidemiological studies in which the natural course of all the disorders in the community can be studied and modifiable risk factors identified and targeted for interventions. It is also vital to study the factors (barriers) affecting better service use, the role of culture and religion in help-seeking behaviors and modifying the identified factors, which may help in better delivery of mental healthcare at the community level. Mental healthcare priority also requires to be shifted from mental hospitals to primary health centers.[60]

Epidemiological studies are expensive and time-consuming. Sponsoring agencies have to be sensitized to contribute to the area of psychiatric epidemiology. Above all this, the scarce availability of resources like manpower, funding, time, practical difficulties in the field and so forth have led researchers to think many times before embarking on psychiatric epidemiological studies, which explains the number of publications in the past ten years. Without addressing these issues we may not be able to move further in this field.[61]

CONCLUSIONS

Mental health problems constitute a wide spectrum ranging from sub-clinical states to very severe forms of disorders. Majority of the epidemiological studies focused on visible mental health problems. Invisible mental health problems continue to remain unexplored and unaddressed. Mental healthcare priorities need to be shifted from psychotic disorders to common mental disorders and from mental hospitals to primary health centers.

Indian psychiatric epidemiological researchers had taken the herculean task of bringing the numbers to the policymakers since 1964. This is truly commendable considering the challenges faced, such as meager human and financial resources. However, their endeavor does not seem to have received the attention that it richly deserves in the national and international arena. Nevertheless it is still not too late to leverage the findings and invest in mental health. Available evidence indicates the overall prevalence rate is approximately 190-200/1000 population. In simple words, at least 20% of the population does have one or the other mental disorder, which requires the mental health professionals’ intervention. This needs to be considered as a modest estimation of the psychiatric prevalence in the Indian population, for policy making. It is high time to stop the long-term debate about the prevalence rate of mental illness in India and move forward to actual actions that call for investing and improving the mental health services in India.

The need of the hour is in addressing major challenges such as lack of mental health manpower, financial aid and stigma, which are the major threats to developing comprehensive psychiatric services in the community. In spite of best efforts, the ratio between psychiatrist and population is worsening day-by-day. Feeble attempts to address the issue of development of manpower in the area of mental health are far from reality. Adding to this, natural and manmade disasters are also placing an enormous challenge on the available meager resources. Increase in invisible mental health problems such as suicidal attempts, aggression and violence, widespread use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, increasing marital discord and divorce rates emphasize the need to prioritize and make a paradigm shift in the strategies to promote and provide appropriate mental health services.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aschengrau A, Seage GR., 3rd . Essentials of epidemiology in public health. Pub: Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, Massachusetts: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Epidemiological studies: A practical guide. 2nd ed. Cambridged, UK: Cambridged University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC. Psychiatric epidemiology: Selected recent advances and future directions. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:464–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, Farmer ME, Knauper B, Kessler RC, et al. Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders: Implications for research and policy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:109–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy JM, Monson RR, Laird NM, Sobol AM, Leighton AH. A comparison of diagnostic interviews for depression in the Stirling County study: Challenges for psychiatric epidemiology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:230–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park K. Preventive and Social Medicine. Pub: M/S Banarsidas Bhanot, Jabalpur, India: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surya NC. Mental morbidity in Pondicherry. Transaction-4, Bangalore: All India Institute of Mental Health. 1964 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Rajkumar S. Three hundred urban families: A psychiatric study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1967;9:280–302. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dube KC. A Study of prevalence and biosocial variables in mental illness in rural and urban community in Uttar Pradesh, India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;46:327–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elnager MN, Maitra P, Rao MN. Mental health in an Indian rural community. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:499–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.546.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Mahendru RK, Kumari P. A psychiatric survey of 500 rural families. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:183–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verghese A, Beig A, Senseman LA, Sundar Rao PS, Benjamin V. A social and psychiatric study of a representative group of families in Vellore town. Indian J Med Res. 1973;61:608–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Mahendru RK, Kumari P. Mental Health and urban life: A study of 850 families. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:243–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.124.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thacore VR, Gupta SC, Suriya M. Psychiatric Morbidity in North Indian Community. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;126:364–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.126.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandi DN, Ajmany S, Ganguly H, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Ghosh A, et al. Psychiatric disorders in a rural community in West Bengal: An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Ganguli H, Ajmany S, Ghosh A, et al. Socio-economic status and prevalence of mental disorders in certain rural communities in India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1979;59:276–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1979.tb06967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah AV, Goswami UA, Maniar RC, Hariwala DC, Sinha BK. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Ahmedabad: An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:384–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta P, Joseph A, Verghese A. An epidemiological study of psychiatric disorders in a rural area in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Psychiatry. 1985;27:153–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sachdeva JS, Singh S, Sidhu BS, Goyal RKD, Singh J. An epidemiological study of psychiatric disorders in rural Faridkot (Punjab) Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:317–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Premrajan KC, Danabalan M, Chandrasekhar R, Srinivasa DK. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in an urban community of Pondicherry. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:99–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaji S, Verghese A, Promodu K, George B, Shibu VP. Prevalence of priority psychiatric disorders in a rural area of Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 1995;37:91–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma S, Singh MM. Prevalence of mental disorders: An epidemiological study In Goa. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:118–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carstairs GM, Kapur RL. The Great University of Kota, London: The Hogarth Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL. Diagnosis and need for treatment are not the same. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:120. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorm F. Mental health literacy, Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padmavati R, Rajkumar S, Srinivasan TN. Schizophrenic patients who were never treated: A study in an Indian urban community. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1113–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan TN, Rajkumar S. Initiating care for untreated schizophrenia patients and results of one-year follow-up. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2001;47:73–80. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins R, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, Gill B, Lewis G, et al. The national psychiatric morbidity surveys of Great Britain: Strategy and methods. Psychol Med. 1997;27:765–74. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700531x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eaton WW, Neufeld K, Chen L, Cai G. Comparison of self-report and clinical diagnostic interviews for depression, Diagnostic Interview Schedule and Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:217–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy MV, Chandrasekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A metaanalysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganguli HC. Epidemiological finding on prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gururaj G, Girish N, Isaac MK. Mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders: Strategies towards a systems approach, NCMH Background Papers-Burden of Disease in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Available from: http://whoindia.org/en/section102/section201_888.htm [accessed on 2009 Sep]

- 35.Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, Blazer DG, et al. The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area program: Historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:934–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Sarkar S, Boral GC, Mukherjee A, et al. A study of psychiatric morbidity of a rural community at an interval of ten years. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:179–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Ghosh A, Nandi PS, Nandi S. Psychiatric morbidity of a rural Indian community: Changes over a 20-year interval. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:351–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nandi DN, Ajmany S, Ganguli H, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Sarkar S. The incidence of mental disorders in one year community in West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1976;18:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Ganguli H, Ajmany S, Boral GC, Ghosh A, Sarkar S. The Natural history of mental disorders in a rural community: A longitudinal field - survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;21:390–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhola P, Kapur M. Child and adoloscent psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:208–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Kumar R, Kumar P. A psychiatric survey of 500 rural families. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:183–96. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verghese A, Beig A. Psychiatric disturbances in children: An epidemiological study. Indian J Med Res. 1974;62:1538–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hackett R, Hackett L, Bhakta P, Gowers S. The prevalence and associations of psychiatric disorder in children in Kerala, South India. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:801–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, Seshadri S, Subbakrishna DK, Bhola P, et al. Epidemiological study of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban and rural areas of Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anita, Gaur DR, Vohra AK, S Subash, Khurana H.Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among 6 to 14 year old children. Indian J Community Med. 2007;28:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Census, 2001. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/India_at_glance/broad.aspx [accessed on 2009 Sep]

- 48.Nandi PS, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP. A study of psychiatric morbidity of elderly population of a rural community in West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:122–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Math SB, Tandon S, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Kumar U, Hamza A, et al. Psychological impact of the tsunami on children and adolescents from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Prim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:31–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Math SB, John JP, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Sunny B, Krishnakanth K, et al. Comparative study of psychiatric morbidity among the displaced and non-displaced populations in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands following the tsunami. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:29–34. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Math SB, Girimaji SC, Benegal V, Uday Kumar GS, Hamza A, Nagaraja D. Tsunami: Psychosocial aspects of Andaman and Nicobar islands: Assessments and intervention in the early phase. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:233–9. doi: 10.1080/09540260600656001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P. 60,000 disaster victims speak, Part I: An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–39. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sen B, Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Mishra DC, Banerjee G, Sarkar S. Psychiatric morbidity in an urban slum-dwelling community. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:185–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in a uprooted community in rural West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:137–42. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banerjee T, Mukherjee SP, Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee A, Sen B, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in an urbanised tribal (Santal) community: A field-survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:243–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Chowdhury AN, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Sen B. Urbanization and mental morbidity in certain tribal communities in West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:334–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Boral GC, Banerjee G, Ghosh A, Ajmany S, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in two tribal communities in certain villages of West Bengal: A cross cultural study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Boral GC, Banerjee G, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, et al. Socioeconomic status and mental morbidity in certain tribes and castes in India: A cross cultural study. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:73–85. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nandi DN, Das NN, Chaudhuri A, Banerjee G, Datta P, Ghosh A, et al. Mental morbidity and urban life: An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:324–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belfer ML. Child and adolescent mental health around the world: Challenges for progress. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2005;1:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chandrashekar CR, Math SB. Psychosomatic disorders in developing countries: Current issues and future challenges. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:201–6. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214349.46411.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]