Abstract

Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) are hormone-regulated transcription factors that regulate a diverse array of biological activities, including metabolism, homeostasis, and development. TRs also serve as tumor suppressors, and aberrant TR function (via mutation, deletion, or altered expression) is associated with a spectrum of both neoplastic and endocrine diseases. A particularly high frequency of TR mutations has been reported in renal clear cell carcinoma (RCCC) and in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We have shown that HCC-TR mutants regulate only a fraction of the genes targeted by wild-type TRs but have gained the ability to regulate other, unique, targets. We have suggested that this altered gene recognition may contribute to the neoplastic phenotype. Here, to determine the generality of this phenomenon, we examined a distinct set of TR mutants associated with RCCC. We report that two different TR mutants, isolated from independent RCCC tumors, possess greatly expanded target gene specificities that extensively overlap one another, but only minimally overlap that of the wild-type TRs, or those of two HCC-TR mutants. Many of the genes targeted by either or both RCCC-TR mutants have been previously implicated in RCCC and include a series of metallothioneins, solute carriers, and genes involved in glycolysis and energy metabolism. We propose as a hypothesis that TR mutations from RCCC and HCC may play tissue-specific roles in carcinogenesis, and that the divergent target gene recognition patterns of TR mutants isolated from the two different types of tumors may arise from different selective pressures during development of RCCC vs. HCC.

Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) are members of a larger family of nuclear hormone receptors. TRs participate in a variety of cellular functions but are best understood in their roles as hormone-regulated transcription factors. In this capacity, TRs bind to specific DNA sequences, denoted “response elements,” and regulate the expression of adjacent target genes (1–4); indirect actions through interactions with other transcription factors are also known. On positive response genes, TRs repress target gene expression in the absence of hormone but activate in the presence of hormone agonist, such as T3 thyronine (5–7). On negative response genes, TRs display the reciprocal transcriptional response: activation in the absence, and repression in the presence of T3 agonist (8–10). Recently, yet additional target genes have been identified that are regulated by TRs constitutively, up or down, in a hormone-independent manner (11). These diverse transcriptional properties reflect the ability of TRs to recruit or release distinct sets of auxiliary proteins, denoted “corepressors” and “coactivators,” so as to yield the corresponding transcriptional outcomes. Corepressors make inhibitory contacts with the general transcriptional machinery and/or modify the chromatin template to impair gene expression; coactivators exert the opposite molecular effects (12–15).

TRs regulate a wide variety of developmental and physiological processes, including control of overall metabolic rate, lipid metabolism, cardiac output, central nervous system development, hearing, and color vision (4, 16–20). TRs in mammals are expressed from two loci, denoted “α” and “β,” and by alternative mRNA splicing to generate a series of receptor isoforms that exert a mix of overlapping and unique biological functions (4, 7). TRα1 and TRβ1 recognize a largely overlapping set of target genes but differ in the magnitude of the transcriptional response they confer once bound to these target genes.

Wild-type (WT) TRs can function as tumor suppressors in certain contexts and can exert profound effects on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (21–23). Mutations that reduce TR expression or alter its function are associated with a variety of neoplasia (24–28). Many of the latter are TR mutations that impair corepressor release in response to T3, resulting in dominant-negative TR mutants that interfere with WT receptor function. For example, a dominant-negative version of TRα1, referred to as “v-Erb A,” contributes to the ability of the avian erythroblastosis retrovirus to induce erythroleukemia in birds (29–35). Similar dominant-negative mutations in human TRα1 and/or TRβ1 have been identified at high frequency in hepatic carcinomas and in renal clear cell carcinomas; these mutations appear spontaneously during tumor progression and are absent from adjacent normal tissues (24, 25). Intriguingly, a distinct set of dominant-negative TRβ mutants in humans produce an inherited endocrine disorder, denoted “resistance to thyroid hormone” (RTH) syndrome, rather than neoplasia (36–38). We have hypothesized that what distinguishes the neoplastic from the endocrine TR mutants is a change in the target gene specificity of the former and have shown that TRα1 and β1 mutants isolated from human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) display target gene repertoires that are distinct from those exhibited by the corresponding WT-TR progenitors (11).

Here, we investigated whether a similar model of oncogenesis applies to renal clear cell carcinoma (RCCC). We asked whether TR mutants associated with RCCC have also undergone changes in target gene specificity, and if so, whether the RCCC-TR target gene spectrum was the same as, or different from, that displayed by the TR mutants isolated from HCC tumors. We report that different TR mutants, isolated from independent RCCC tumors, possess expanded target gene specificities that extensively overlap one another, but only minimally overlap that of the WT-TRs, those of two HCC-TR mutants, or that of an RTH-TR mutant. We propose as a hypothesis that these TR mutants distort the WT receptor's transcriptional properties so as to shift the normal gene expression program to one that is cancer promoting. As a corollary of this hypothesis, we further suggest that TRs may be subjected to different selective pressures during hepatic and renal clear cell tumor progression, thereby resulting in TR mutants with distinct target gene preferences and tissue-specific functions. Therefore, although each TR mutant displays a unique overall combination of biochemical properties, our results suggest that a change in target gene repertoire is a frequent consequence of the TR mutations that appear to accumulate in these neoplasia.

Results

RCCC-TR mutants have gained the ability to repress an expanded set of target genes that are distinct from those recognized by the WT-TRs and the HCC-TR mutants

To compare the target gene repertoires of TR mutants isolated from human RCCC to those regulated by WT-TRs and by TR mutants isolated from HCC, we created HepG2 cells stably expressing the corresponding receptors. We chose this cell line because it retains the molecular machinery necessary to respond to T3 hormone, yet expresses relatively low levels of endogenous TRs, permitting the target gene repertoire of an ectopically introduced TR to be readily discerned above the endogenous background (39–44). These cells allowed us to compare the intrinsic target gene specificities of the different TRs in a single cell context without introducing further complexities arising from use of different cell types or resulting from global changes in gene expression in response to oncogenic initiation.

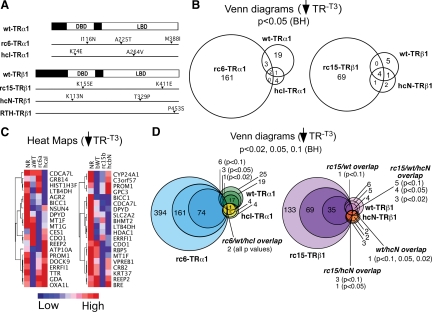

We tested RCCC-TR mutants isolated from two different tumors: one in TRα1 (denoted “rc6”) and one in TRβ1 (denoted “rc15”) (Fig. 1A). In common with the HCC-TR mutants, these RCCC-TR mutants can repress, but are impaired in gene activation in response to T3, in at least certain contexts, and can behave as dominant-negative inhibitors when coexpressed with WT-TR. Similarly, we and others have observed altered DNA-binding characteristics for these mutants in vitro [although the specifics have somewhat varied, most likely due to differences in the details of the experimental approaches (25, 39, 45)]. For comparison, analogous HepG2 transformants expressing WT-TRα1, WT-TRβ1, an HCC-TRα1 mutant, an HCC-TRβ1 mutant, or bearing an empty vector control were analyzed in parallel. The properties of these mutants are summarized in Supplemental Fig. 1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org. All six of the TR alleles analyzed can repress artificial reporter genes in the absence of hormone (39, 45); we therefore focused the first arm of our array analysis on identifying the cellular genes that were repressed by a given TR, compared with the empty vector control, in the absence of T3 (e.g. ↓TR−T3). A three-way comparison was performed for each TR isoform (RCCC vs. HCC vs. WT). Interestingly, both the RCCC-TRα1 and RCCC-TRβ1 mutants repressed a greatly expanded set of target genes compared with their respective WT-TR alleles (Fig. 1B). The vast majority of these newly identified target genes were unique to the RCCC mutants and were not shared by the WT-TRs or by the HCC mutants. Only two genes, BICC1 and DPYD, were repressed by all six TR alleles. The WT-TR targets included genes, such as G6PD and C1S, identified in prior studies of T3 regulation in liver cells. A complete list detailing the genes identified in this analysis is presented in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

In the absence of hormone, RCCC-TR mutants repress a broad set of genes distinct from those repressed by WT- or HCC-TRs. A, Schematic of the WT and mutant TRs employed. The DBD and ligand-binding domains are shown, as are the locations of the relevant mutations (arrowheads). B, Venn diagrams of genes repressed by the different TR alleles; minus T3. RNA was isolated from stable transformants expressing the TR indicated and treated with carrier only. Gene expression levels were determined by microarray analysis as in Materials and Methods. Data were analyzed using a BH adjusted P value of <0.05 to identify genes repressed in each TR transformant compared with the vector-only control. C, Heat map clustering of representative repressed genes. Expression level of each gene is indicated by color (see key below panel). D, Venn diagrams of genes repressed by the different TRs, adjusted to different statistical cutoffs. Genes repressed in the absence of T3 by WT-TRα1 (green), WT-TRβ1 (pink), rc6-TRα1 (blue), rc15-TRβ1 (purple), hcI-TRα1 (yellow), or hcN-TRβ1 (orange) were identified as in panel B, but using BH-adjusted P values of <0.02 (darkest shades), 0.05 (intermediate shades), and 0.1 (lightest shades).

The lack of substantial target gene overlap between the RCCC and HCC mutants was unexpected: only two of the 166 genes flagged as repressed by the RCCC-TRα1 mutant were also flagged as repressed by the HCC-TRα1 mutant (BICC1 and DPYD), and only five of the 74 genes repressed by the RCCC-TRβ1 mutant were also flagged as repressed by the HCC-TRβ1 mutant (RBP5, BICC1, CDCA7L, DPYD, LTB4DH) (Fig. 1C). Even this limited overlap between the RCCC and HCC targets did not represent an exclusively oncogenic signature: both of the target genes repressed in common by rc6-TRα1 and hcI-TRα1 (BICC1 and DPYD), and all but one (RBP5) of the target genes repressed in common by the rc15-TRβ1 and hcN-TRβ1 mutants, were also regulated by the corresponding WT receptor (Fig. 1). In fact, certain genes repressed by the RCCC-TR mutant were activated by the corresponding WT- or HCC-TRα1 (e.g. CES1; Fig. 1C). Although we chose P < 0.05 as an arbitrary cutoff value for this analysis, similarly limited overlaps were observed between the RCCC-TR mutant target panel and that of the WT or HCC-TRs using other P values (see extended Venn Diagrams, Fig. 1, D and E).

The RCCC-TRα1 and RCCC-TRβ1 receptors repress an extensively shared, extended set of genes that are distinct from those targeted by WT-TRs or HCC-TR mutants

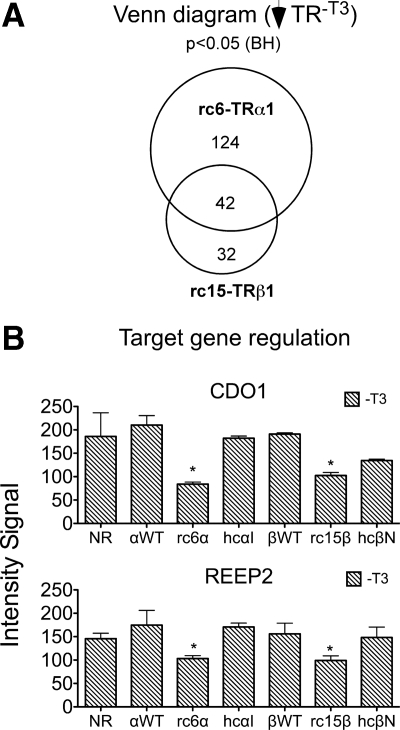

Of the 166 genes called out by our initial analysis as repressed by rc6-TRα1, 42 were also significantly repressed by rc15-TRβ1 (an overlap of 25%); reciprocally, these 42 overlapping genes represent 57% of the 74 genes flagged as repressed by rc15-TRβ1 (Fig. 2A). Two representative genes within this overlapping set, CDO1 and REEP2, are shown in Fig. 2B [also validated with quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR); Supplemental Fig. 2]. We recognized that our use of a Benjamini-Hochberg (BH)-adjusted P value to minimize the false-positive discovery rate in our initial analysis might have obscured, by excluding authentic positives, the true extent of the overlap between the TRα1 and TRβ1 mutants. Inspection of individual genes supported this concept: ATP5H and RNF5, for example, were flagged by our bulk analysis as only significantly repressed by rc6-TRα1, although on pair-wise analysis they also appeared to be repressed by rc15-TRβ1 (Fig. 3A). Conversely, LOC51152 and VPREB1 were flagged as only regulated by rc15-TRβ1 but on pair-wise analysis also appeared to respond to rc6-TRα1 (Fig. 3B). We therefore next performed a two-step analysis that first employed the BH-adjusted P value to minimize the false discovery rate, followed by the unadjusted P value to indicate probability of repression (see Materials and Methods). Using this criterion, an additional panel of target genes was identified that met a P < 0.05 cut-off as repressed by both rc6-TRα1 and by rc15-TRβ1 (Fig. 3C). Although this analysis also expanded the overlap between the RCCC-TR target genes and those regulated by the WT-TRs or HCC-TRs, the majority of the RCCC-TR target genes remained unique even under this extended statistical test (Fig. 3D). We conclude that, although arising from different tumors and from different genetic loci, the two RCCC mutants, rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1, repress an extensive overlapping set of mutual target genes that are distinct from those recognized by the corresponding WT or HCC mutant TR.

Fig. 2.

RCCC-TR mutants repress a shared set of target genes. A, Venn diagram of genes repressed by rc6-TRα1 compared with those repressed by rc15-TRβ1; minus T3. B, Microarray intensity signals of two representative target genes repressed in the absence of T3 by both rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1. Asterisks indicate significant repression (BH adjusted P value of <0.05) in the TR transformant vs. the empty vector control. The mean and sem values from three independent experiments are shown. NR, No receptor/empty vector.

Fig. 3.

Additional statistical analysis reveals an extensive overlap between target genes repressed by rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1. A, Microarray intensity signals of two target genes identified as repressed by rc6-TRα1, subsequently assayed for regulation by other TR alleles. Double asterisks indicate significant repression (BH-adjusted P value of <0.05) in the TR transformant vs. the empty vector control. Single asterisks indicate a potentially significant repression using a nonadjusted P value of <0.05 (see Materials and Methods). B, Microarray intensity signals of two target genes identified as repressed by rc15-TRβ1, subsequently assayed for regulation by other TR alleles as in panel A. C, Venn diagram comparing gene repressed in the absence of T3 by rc6-TRα1 vs. rc15-TRβ1. A two-step analysis was employed beginning with the genes identified in Fig. 2A and applying a second, nonadjusted P value of <0.05 (see Materials and Methods). D, Venn diagrams comparing genes repressed by WT and mutant TRα1 or WT and mutant TRβ1 in the absence of hormone. A two-step analysis was employed beginning with the genes identified in Fig. 1B and using a nonadjusted P value of <0.05 (see Materials and Methods). NA, Not applicable; NR, no receptor/empty vector.

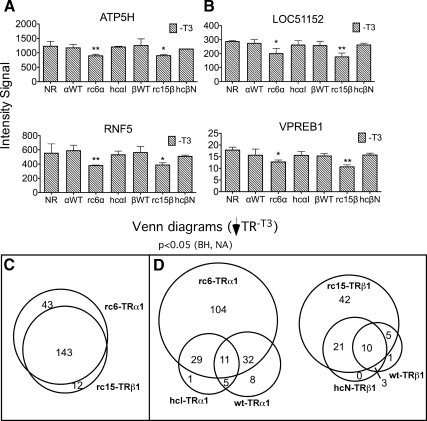

The majority of RCCC-target genes repressed in the absence of T3 hormone were also repressed in its presence

We next examined whether the target genes repressed by the RCCC-TRs mutants in the absence of hormone could respond to T3 (Fig. 4). Paralleling our observations on the HCC-TR mutants (11), the majority of the genes repressed by the RCCC-TRs were not significantly affected by the addition of T3 (e.g. MT1F, MT1G; Fig. 4A). In the cases in which the RCCC-TR target genes overlapped those regulated by WT-TRs, most were constitutively repressed by both the RCCC and the WT receptors (Supplemental Table 1). A much smaller panel of genes repressed by the RCCC-TR mutants was partially derepressed by T3 (e.g. KRT37 in Fig. 4A); this is consistent with the retention of at least some T3 binding by these mutants (Ref. 45 and Supplemental Fig. 1), A final subgroup of RCCC-TR target genes was slightly more repressed in the presence than in the absence of T3; these may represent negative response genes, although they are at the edge of statistical significance (e.g. MT1J, C1orf51; Fig. 4B). Several of the T3-responsive RCCC target genes exhibited the same hormone response, down or up, in the WT or HCC transformants. We confirmed representative examples of these different gene panels by qRT-PCR (Supplemental Fig. 2 and data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Repression by RCCC-TR mutants is largely independent of T3. A, Microarray intensity signals of three target genes flagged as repressed by RCCC-TRs in the absence of T3 (Fig. 2A), subsequently compared with and without T3. Asterisks indicate significant repression (BH adjusted P value of <0.05) in the TR transformant vs. the empty vector control. B, Microarray intensity signals of additional RCCC-TR target genes flagged as repressed by RCCC-TRs in the presence of hormone (BH-adjusted P value of <0.05), subsequently compared with or without T3. The mean and sem values from three independent experiments are shown. NR, No receptor/empty vector.

To discover any additional RCCC-TR negative response targets, we next identified genes that were repressed in the RCCC-TR transformants, but not in the vector-only controls, in the presence of T3 (i.e. ↓TR+T3). (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Most of the genes previously identified as repressed in the absence of T3 were also repressed in the presence of T3 (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Further, a small set of additional genes was identified as repressed in the T3-treated RCCC-TR transformants compared with the T3-treated vector-only controls (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Individual analysis demonstrated that these newly identified genes were likely also repressed in the absence of T3, but fell just below the P value constraints we imposed in our analysis. We conclude that the majority of target genes repressed by either the RCCC-TRα1 or RCCC-TRβ1 mutant are regulated in a hormone-independent, constitutive manner, although a limited number of these targets display a very restricted ability to respond, down or up, to T3 hormone.

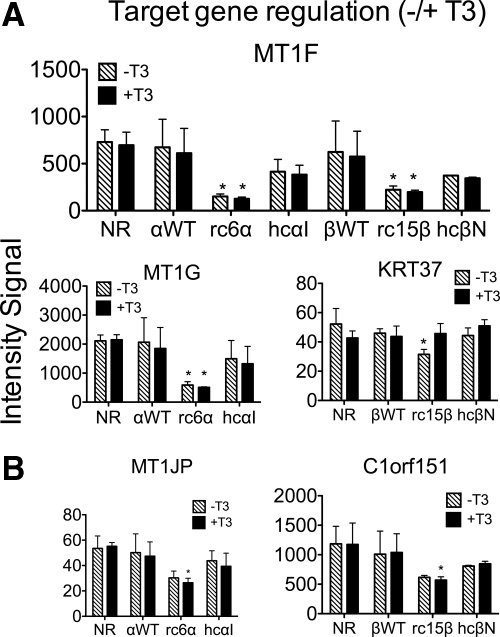

The RCCC-TRα1 and β1 mutants are more than broad transcriptional repressors; they also activate a large, mostly shared set of additional target genes not recognized by the other TRs tested

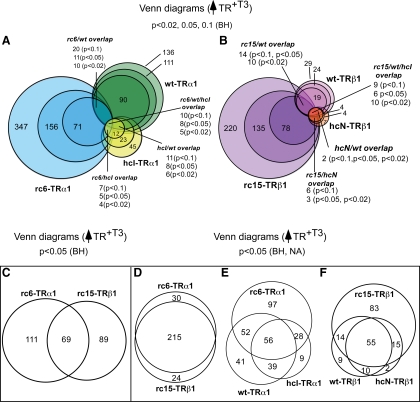

Because the RCCC-TR mutants display at least some ability to respond to T3 in reporter assays (Ref. 45 and Supplemental Fig. 1), we next sought to identify endogenous genes activated by the RCCC-TR mutants in response to hormone, compared with vector-only transformants (i.e. ↑TR+T3). Interestingly, both the RCCC-TRα1 and RCCC-TRβ1 mutants activated large sets of target genes under these conditions that (depending on the P value chosen) approximated or exceeded the number of target genes activated by the corresponding WT-TR isoforms when analyzed in parallel (Fig. 5, A and B). As was noted for genes repressed by these mutants, there was a substantial overlap between the genes activated by the RCCC-TRα1 mutant and those activated by the RCCC-TRβ1 mutant (Fig. 5C). Even under our most stringent P value restriction, 38% of the genes activated by rc6-TRα1 were also flagged as activated by rc15-TRβ1; reciprocally, 44% of the target genes activated by rc15-TRβ1 were also activated by rc6-TRα. When subjected to the two-step analysis described previously, the overlap between the genes activated by rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1 rose to nearly 80% (Fig. 5D). Although the overlap between these RCCC-target genes and those activated by the WT or HCCC mutants was also expanded by the two-step analysis, approximately half of the activated target genes remained unique to the RCCC-TRs (Fig. 5, E and F). It should be noted that although both the RCCC-TRα1 mutant and RCCC-TRβ1 mutant activate a highly overlapping set of target genes, the magnitude of this activation at each target gene sometimes differed for the two different receptor mutants (e.g. ATP5; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Representative genes were validated by qRT-PCR (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

RCCC-TR mutants activate an extended set of genes that are not targeted by the WT or HCC-TR mutants. A and B, Venn diagrams of genes activated by WT-TRα1 (green), WT-TRβ1 (pink), rc6-TRα1 (blue), RC15-TRβ1 (purple), hcI-TRα1 (yellow), or hcN-TRβ1 (orange) in the presence of T3 are shown, using BH-adjusted P values of <0.02 (darkest shades), 0.05 (intermediate shades), and 0.1 (lightest shades). C, Venn diagram of genes activated in the presence of T3 by rc6-TRα1 vs. rc15-TRβ1 (BH-adjusted P value of <0.05). D, Venn diagram comparing genes activated in the presence of T3 by rc6-TRα1 vs. rc15-TRβ1, using a two-step analysis as described in Fig. 3C. E and F, Venn diagrams comparing genes activated by the different TR alleles in the presence of T3, using a two-step analysis as described in Fig. 3D.

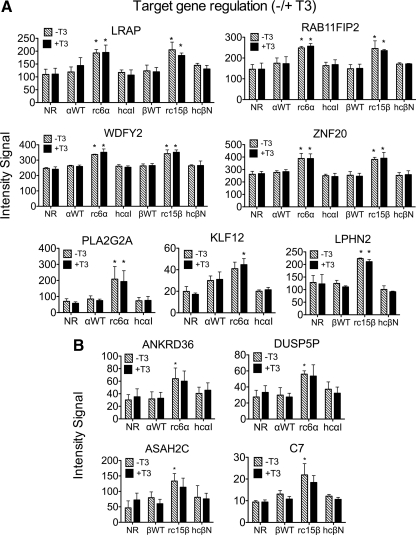

We next examined the expression of these same genes in the absence of T3. Notably, nearly all of the genes flagged as activated by the RCCC-TR mutants were also activated in the absence of T3 (relative to the vector-only transformants) (Fig. 6, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Fig. 3). In the few cases in which T3 either further induced or further attenuated expression of a given target gene, the effect of the hormone was very modest (e.g. WDFY2, Fig. 6). To identify the hypothetical fourth class of RCCC-TR target genes, those that are activated by the RCCC-TR mutants only in the absence of T3 (obligate negative-response genes), we compared genes induced in the RCCC-TR vs. vector-only transformants in the absence of T3 (i.e. ↑TR−T3). As expected, most of the genes identified in this fashion overlapped with those identified as activated in the presence of T3 (i.e. genes that were activated both in the absence and presence of T3; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). In addition, however, a set of novel genes were identified as activated in the untreated RCCC-TR transformants that had not been flagged as activated in the presence of T3 (e.g. ANKRD36, DUSP5P, ASAH2C, and C7; Fig. 6B and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Individual analysis, however, demonstrated that these newly identified genes were likely also activated in the absence of T3 but fell just below the P value constraints we imposed in our analysis. We conclude that the RCCC-TRα1 and β1 mutants display a convergent repertoire of target genes that are activated by these mutants in a largely hormone-independent fashion, and this RCCC-TR target gene repertoire is highly distinct from those regulated by the corresponding WT-TR or HCC-TR mutant.

Fig. 6.

Activation by the RCCC-TR mutants is largely independent of T3. A, Microarray intensity signals of six target genes flagged as activated by RCCC-TRs in the presence of T3 (Fig. 5), subsequently compared with and without T3. Asterisks indicate a significant activation (BH-adjusted P value of <0.05) in the TR transformant vs. the empty vector control. B, Microarray intensity signals of additional target genes flagged as activated by RCCC-TRs in the absence of hormone (BH-adjusted P value of <0.05), subsequently compared with and without T3. The mean and sem values from three independent experiments are shown. NR, No receptor/empty vector.

An RTH mutant, P453S, has a unique signature of transcription regulation distinct from both that of the WT and the neoplasia-associated TRs

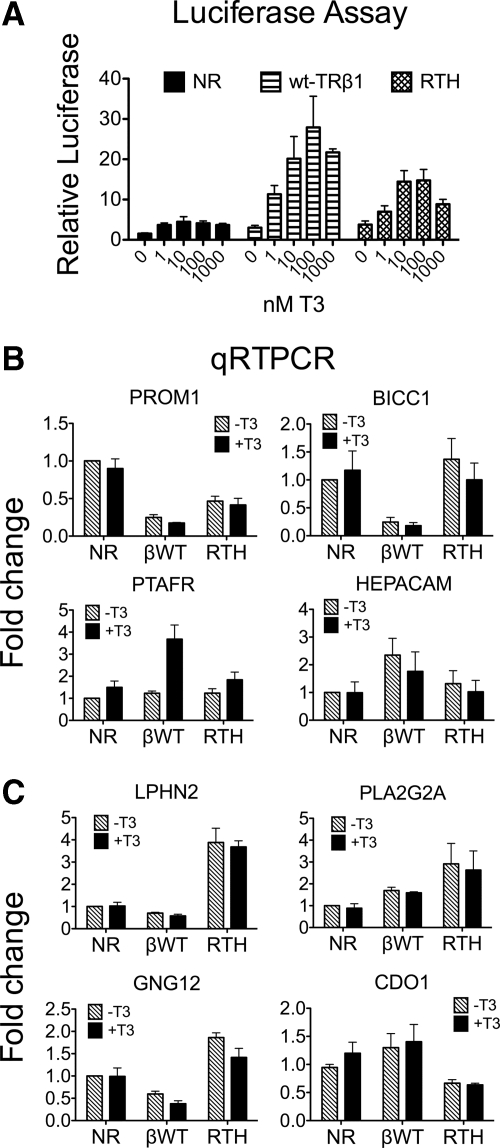

Our model entering these studies was that a TR mutant associated with endocrine, rather than neoplastic, disease would be attenuated in its ability to activate target genes in response to T3, but would nonetheless display a WT target gene specificity. To test this premise, we created stable HepG2 cells expressing an RTH-TRβ1 mutant (representing a P453S amino acid substitution). In common with the HCC and RCCC mutants, the RTH mutant is impaired in its ability to release from corepressors and to bind coactivators in response to T3 in vitro and behaves as a strong, dominant-negative inhibitor of WT-TR function when cointroduced into CV-1 cells (46). Unlike the HCC-TR and RCCC-TR mutants tested above, however, the P453S-TR mutant contains only the single substitution in its hormone-binding domain and does not possess any mutation within its DNA-binding domain (DBD)(47). We first examined the ability of P453S-TRβ1 to regulate an ectopically introduced DR4-tk-luciferase reporter gene. Reporter gene expression in the empty-vector transformants minus T3 was very low and displayed a very limited induction to T3 (presumably mediated by the low levels of endogenous TRs in these cells) (Fig. 7A). Although the WT-TRβ1 transformants displayed a strong, T3-inducible luciferase response, the luciferase response in the RTH-TRβ1 transformants was clearly attenuated (Fig. 7A). These results confirm prior observations in CV-1 cells that this mutant receptor is impaired, but is not completely ablated, in its ability to activate transcription of a consensus reporter gene (46).

Fig. 7.

An RTH-TRβ1 mutant displays impaired transcriptional properties and a unique gene expression signature. A, Reporter gene assays. Cells stably expressing WT-TRβ1, P453S-TRβ1, or an empty vector were transiently transfected with a DR4-TK-luciferase reporter and pCH110-lacZ as an internal control. The cells were treated with T3 as indicated 24 h after transfection, harvested 48 h after transfection, and analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Luciferase activity is shown relative to β-galactosidase activity. B, qRT-PCR assays on four genes known to be WT-TR targets. Cells transformed with WT-TRβ1, RTH-TRβ1, or an empty vector control, were treated with with and without 100 nm T3 for 6 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed by qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers. C, qRT-PCR assays on additional genes. Assay was as in panel B. Expression of each gene in the empty vector control in the absence of T3 is defined as = 1; the mean and sem values from three independent experiments are shown. NR, No receptor/empty vector.

We next examined endogenous gene expression after treating the RTH-TRβ1 transformants with or without T3. We used qRT-PCR to assay representative genes from the panel of HepG2 genes previously identified as regulated by WT-TRs. The RTH mutant behaved on many of these endogenous targets as it did on the artificial reporter: it retained the ability to repress several genes that are targets of repression by WT-TRβ1 in the absence of T3 (e.g. PROM1) and failed to activate certain genes (e.g. PTAFR, and HEPACAM), that are activated by WT-TRβ1 (Fig. 7B). Nonetheless, the RTH mutant's repressive profile did not completely coincide with that of WT-TRβ1. BICC1 expression, for example, was not detectably affected by the RTH mutant, although this gene was strongly repressed by all other receptors tested (Fig. 7B and Supplemental Fig. 4). Additional differences became evident when we expanded our analysis to genes that were regulated by the RCCC or HCC mutants, but not by WT-TRs (Fig. 7C). For example, the RTH-TRβ1 mutant repressed CDO1, a gene that was also repressed by both the RCCC-TRα1 and RCCC-TRβ1 mutants, but was not regulated by either WT-TR isoform (Fig. 7C). Reciprocally, the RTH-TRβ1 mutant activated LPHN2 and PLA2G2A (targets activated by rc15-TRβ1 and rc6-TRα1 respectively, but not by the corresponding WT-TRs) and GNG12 (a target activated by both HCC-TR mutants, but which is repressed by WT-TRβ1 (Fig. 7C) (11). Nonetheless, the RTH-TRβ1 mutant failed to repress REEP2, an RCCC-TR target gene, and had no regulatory effect on the panel of metallothionein genes that are among the prominent targets of RCCC-TR regulation (Supplemental Fig. 4). We conclude that TR mutants associated with endocrine disorders retain the ability to regulate certain gene targets, lose the ability to regulate others, and perhaps most surprising (given their WT DBD), have gained the ability to modulate target genes not regulated by the corresponding WT-TRs.

Discussion

RCCC-TR mutants repress an augmented panel of genes that are largely T3 independent and not recognized by WT receptors or by HCC-TR mutants

Mutated TRs have been identified in many types of neoplasia including thyroid and gastric carcinomas as well as RCCC, HCC, and avian erythroleukemia (24–28, 31, 32). These mutant alleles typically bear multiple amino acid substitutions that encompass both the receptor's DNA recognition and hormone-binding domains, function as dominant-negative inhibitors when coexpressed with WT receptor, and often display altered DNA-binding properties in vitro (39, 45, 48, 49). We have proposed that the altered DNA binding properties of these mutants allow them to confer a divergent regulatory program from that of the WT receptor (11). Consistent with this idea, HCC-TR mutants were found to regulate a unique set of genes that were not recognized by the WT receptors (11).

In the present study, we sought to determine whether alterations in the normal target gene repertoire are a general phenomenon in multiple neoplasias, and if so, whether tissue-origin-specific or shared target genes could be identified. We report that two TR mutants originally isolated from two different human RCCC (rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1) repress a greatly expanded set of gene targets compared with the corresponding WT or HCC isoforms, whereas very few of the genes regulated by WT-TRs or HCC-TRs are regulated by either RCCC-TR mutant. Notably, an extensive overlap was observed between the genes repressed by rc6-TRα1 and those repressed by rc15-TRβ1, despite these mutants bearing different amino acid substitutions, displaying different consensus DNA- and T3-binding properties, and arising from different isoforms. Using our most stringent statistical analysis, there was a 21% overlap between the genes repressed by the rc6-TRα1 mutant and those repressed by the rc15-TRβ1 mutant, but only a 3% to 6% overlap between the RCCC-TR targets and those of the WT or HCC-TR target genes. A less stringent, two-step statistical approach indicates that the overlap between the target genes repressed by the two RCCC-TR mutants might be as high as 72%. We hypothesize that this convergence between the rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1 target gene repertoires reflects a selection during oncogenesis for TR mutants able to recognize certain key target genes involved in mediating the RCCC tumor phenotype. However, it should be noted that approximately 5% of RCCC tumors bear mutations in both TRα1 and in TRβ1, suggesting that the nonoverlapping components of the target gene repertoires of these TR mutants may also confer a selective advantage to certain tumors when combined (in fact, the rc6-TRα1 was isolated from a tumor also bearing a TRβ1 mutation). Additional TR mutants from additional tumors will need to be analyzed to establish whether this apparent link between target gene specificity and tumor-type of origin extends more broadly than the limited alleles studied here. We are also currently testing whether specific TR mutants mediate a corresponding tissue-specific tumorigenesis when expressed in transgenic mice or when tested for transforming capacity ex vivo.

The extensive overlap between the rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1 target gene sets is particularly intriguing given that the mutations in the DBD of these receptors are nonidentical (Fig. 1). The rc15-TRβ1 mutant contains a K155E substitution in the DBD helix 3, a region that contacts the DNA minor groove and helps recognize the −2 and −1 bases flanking the canonical hexanucleotide half-site. The rc6-TRα1 mutant contains an I116N substitution within DBD helix 2, a region that stabilizes the overall structure of the DBD but does not appear to make direct contacts with DNA. It is conceivable, based on their locations, that both substitutions broaden the target gene repertoire by broadening the receptors' ability to recognize difference sequences at the −1 and −2 positions.

Alternatively, the divergent transcriptional programs mediated by the RCCC vs. WT receptors may reflect differences in their ability to recruit specific coregulators once bound to a given target gene, perhaps as a consequence of the mutations in their hormone-binding domains. For example, the RCCC-TR, HCC-TR, and WT-TR mutants differ in a variety of properties, including their ability to recruit specific corepressors and coactivators. We have suggested that WT TRα1 and TRβ1 display target gene-specific transcriptional responses due, at least in part, to differences in their ability to recruit coregulators once these TR isoforms are bound to a given response element; a similar phenomenon may be occurring with the mutant receptors. The different WT and mutant TRs may also differ in their ability to interact with pioneer proteins that help recruit these receptors to specific target genes or in their ability to participate in the long distance synergistic interactions that occur between receptors bound to different response elements and that contribute to combinatorial gene regulation. Finally, it should be noted that WT-TRs regulate a subset of their target genes through protein-protein contacts with other transcription factors, and at least part of the target gene repertoire of the mutant TRs may be mediated through this tethering mechanism.

Although endogenous TR expression is modest in the HepG2 cells employed here, it is still discernible. It is likely that different HCC or RCCC tumors express different ratios of mutant to WT TRs and therefore display different ratios of the corresponding target gene repertories. Tumors expressing very high levels of mutant TR expression may, in fact, confer regulation of additional target genes beyond those detected here. Further, if WT TRs are able to dimerize with mutant TRs, these mixed homodimers may gain a novel target gene specificity unrelated to that of the corresponding WT-TR/RXR, mutant-TR/RXR, WT-TR/WT-TR, or mutant-TR/mutant-TR dimers.

The HCC-TR mutants were expressed at lower mRNA levels than were the RCCC-TR or WT-TR alleles; further, due to technical problems relating to a lack of suitable antisera, we were unable to quantify the TR protein levels in the different transformants. We therefore considered whether the different target gene repertoires observed for these mutants might be a result of differences in TR abundance, rather than TR specificity, in these transformants. However, we concluded that this is unlikely for a variety of reasons. 1) The TR expression constructs share an identical architecture, and the translational efficiency and stability of the different WT and mutant TRs were nearly indistinguishable in in vitro translations and in transient transfections of other cell lines. 2) If the levels of the different TRs were playing a determinant role, the transformants expressing lower levels of a given TR protein would be expected to mediate correspondingly lower levels of regulation of all target genes; this was not observed. Instead, a panel of genes recognized in common by both WT and mutant TR alleles were regulated to the same magnitude in the different transformants (Supplemental Fig. 8). 3) Similarly, if the abundance of the different TRs was playing a major role in defining the breadth of the transcriptional response in these cells, then the number of target genes detected by the array would be expected to expand as the levels of TR protein increased. However, this was not the pattern observed in our experiments. Instead, all mutants displayed both gains and losses in their target gene repertoire. For example, the HCC TR tranformants are expressed at lower mRNA levels than the other alleles tested, but instead of exhibiting a general impairment of all target gene regulation, they display a switch to a distinct set of regulated genes, with the absolute number of HCC targets remaining approximately the same as the absolute number of targets for the (more abundantly expressed) WT-TRs (e.g. 46 vs. 56 targets are repressed by WT-TRα1 vs. hcI-TRα1, with 30 of these novel to the HCC mutant, and 31 vs. 16 targets are repressed by hcN-TRβ1 vs. wt-TRβ1, with 21 of these unique to the HCC mutant). 4) Conversely, although the RCCC-TR mutants have gained the ability to regulate an expanded set of target genes compared with the WT-TRs, the RCCC-TRs have also lost the ability to regulate genes that are recognized by the WT-TRs, a finding that difficult to attribute to a hypothetical overexpression of the RCCC-TR proteins. We therefore believe that the differing target gene repertoires of the different TR alleles are not a simply a result of differing levels of TR expression but, instead, represent an inherent, specific change in target gene recognition.

RCCC-TR mutants are also able to constitutively activate a large panel of target genes not recognized by the WT or HCCC receptors

In addition to the genes that are repressed by the RCCC-TR mutants (above), we also identified a further category of genes that were activated by these mutants. Interestingly, this activation was constitutive for most of the targets identified (e.g. these genes were up-regulated by the RCCC mutants in both the absence and presence of T3). We have previously reported a similar phenomenon for the WT- and HCC-TRs, which in addition to their T3-regulated repertoire, also activate a subset of their target genes in a hormone-independent fashion (11). We suggest that this constitutive transcriptional activation represents, at least in part, the actions of the N-terminal A/B domains of these receptors, which can recruit coactivators and activate transcription in the absence of hormone agonist.

Mirroring our observations on repression, substantially more target genes were up-regulated by the RCCC-TRs than were up-regulated by the WT- or HCC-TRs, and there was extensive overlap between the rc6-TRα1- and rc15-TRβ1-activated targets (26% overlap by the stringent BH-corrected analysis, and up to 80% by our two-step analysis). Also, as first noted for repression, relatively few of the genes up-regulated by either the WT- or HCC-TRs were also up-regulated by the RCCC-TRs, although there was slightly more overlap among the up-regulated genes than among the down-regulated genes.

The current study was performed in HepG2 cells of hepatic origin to permit us to first compare the target gene specificity of the different TR alleles in a single type of cell. Clearly the cell background contributes to the specificity of different nuclear receptors and is likely to influence the target gene specificity of both the WT and mutant TRs tested here. In that regard, we have begun studies of these same TR alleles in other cell lines; our preliminary analyses of gene expression profiles in a human kidney cell line (HEK293T) stably transformed with the RCCC-TR mutants, HCC-TR mutants, WT receptors, or an empty vector control support the divergent regulatory programs observed in the HepG2 stables. Several genes we examined were regulated in an RCCC-TR mutant-specific manner, although the extent and direction of regulation appeared to be strongly influenced by cell type (data not shown). We hope to extend these experiments in the future.

The RCCC-TR repertoire includes genes previously associated with RCCC and/or other neoplasia

We previously described a comparison between the HCC-TR target genes and known changes in gene expression in HCC tumors (11). A similar examination of the RCCC-TR target gene data set revealed genes previously implicated in RCCC tumorigenesis. Among the most prominent of these were the metallothioneins. Metallothioneins are metal-ion-binding proteins that are misregulated in several tumor types, including RCCC, and display many of the properties of tumor suppressors (50). For example, MT1F is frequently deregulated in primary RCCC tumors and was repressed by both the rc6-TRα1 and the rc15-TRβ1 mutants in our study. Using our two-step statistical analysis, many additional metallothioneins (MT1A, MT1DP, MT1E, MT1G, and MT1L) were also identified as repressed by both rcTR mutants. Similarly, the RCCC-TR mutants gained the ability to regulate a wide range of solute carriers, including both plasma membrane and mitochondrial ion transporters. For example, rc6-TRα1, but not WT-TRα1, activated expression of SLC2A1 and repressed expression of SLC2A9; both are glucose transporters and aberrant expression of other members of the same family (e.g. SLC2A5) are known markers of RCCC (52). The RCCC-TR mutants also targeted several genes involved in glycolysis and energy metabolism. For example, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1, was induced by the rc15-TRβ1, but not by any of the other TRs tested; an isoenzyme of this kinase (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4) is frequently overexpressed in RCCC (52).

We also observed a statistically significant, although slight, up-regulation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL) in the rc6-TRα1 and rc15-TRβ1 transformants (the former only under our less-restrictive two-step analysis). Inactivation of VHL protein by inherited or spontaneous mutations is a classic hallmark of RCCC and results in the misregulation of panels of genes involved in cell growth, invasion, and angiogenesis (53–57). The ability of the RCCC-TR mutants to up-regulate VHL expression was unexpected, and it is possible that this is an initial step in the process that ultimately leads to its silencing or mutagenesis in RCCC tumors. Conversely, loss of regulation of certain genes by the RCCC mutants may also contribute to tumorigenesis. For example, wt-TRα1 and wt-TRβ1, but not the RCCC-mutants, repress ERRFI1 and activate TRIB2. ERRFI1 is a cytoplasmic protein that has been linked to cell growth and TRIB2 is a proapoptoic protein that targets hematopoietic cells (58, 59).

Is there a common TR oncogenic signature shared by multiple types of cancer?

The majority of the target genes repressed or induced by the two RCCC-TR mutants tested here were not targeted by the two HCC mutants we examined. However, there were several interesting exceptions. At a P < 0.05 cutoff, five genes (BBS5, EPB41L1, GLT25D2, HSPA12A, NRCAM) were activated by both rc6-TRα1 and hcI-TRα1 but not the WT-TRα1 isoform, and three genes (EPB41L1, GLT25D2, UGTA3) were activated by both rc15-TRβ1 and hcN-TRβ1, and not WT-TRβ1. Interestingly, two of these genes (EPB41L1 and GLT25D2) were activated in all tumor-associated TRs analyzed; a potential role for these genes in cancer initiation or progression has not yet been determined. One gene (RBP5) repressed by the RCCC- and HCC-TRβ mutants was not repressed by the WT-TRβ1 receptor, whereas two additional genes repressed by the HCC and RCCC-TRs (BICC1 and DPYD) were also repressed by WT-TRs. Our two-step statistical analysis revealed several further overlaps between the RCCC and HCC targets. For example, several of the metallothionein genes targeted by the RCCC-TR mutants were also weak targets of repression by the HCC-TR mutants, and it is notable that metallothionein genes have been shown to be down-regulated not only in RCCC, but also in certain HCC (60–62). Additional target gene overlaps between HCC- and RCCC-TR mutants are presented in Fig. 3C.

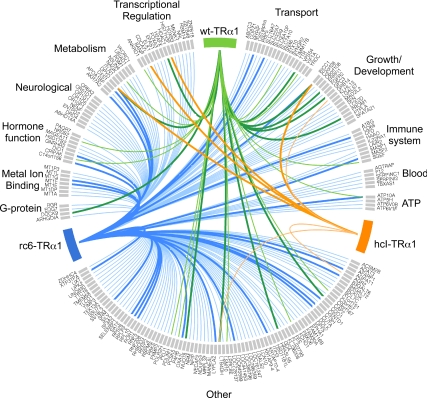

To comprehensively present this data in a novel, visual way, we displayed the relationships between the genes targeted by the different TR alleles by adapting Circos, an open source software originally designed for comparisons of genomic data. In Fig. 8, we arrayed each gene flagged as repressed by WT-TRα1, by rc6-TRα1, or by HCC-TRα1 on the perimeter of a circle, grouped into categories based upon their Entrez descriptions. Genes that are repressed by the WT-TRα1 receptor are indicated by lines that emanate from the green TRα1 rectangle. Blue and orange rectangles/lines serve the same function for the RCC or HCC-TRα1 receptors, respectively. The width of each line reflects the statistical confidence that the gene is repressed relative to the no-receptor control. Genes repressed by more than one receptor are therefore identifiable by convergent colored lines (e.g. BICC1). Corresponding Circos plots are provided for TRβ1 and for genes activated rather than repressed by a given receptor (Supplemental Figs. 5–7). We believe this type of presentation allows easy comprehension of the relationships between multiple nuclear receptors and their regulatory targets.

Fig. 8.

Comprehensive illustration of all genes repressed by one or more TRα allele in the absence of T3. All genes repressed by rc6-TRα1, hcI-TRα1, and WT-TRα1 in the absence of hormone (as depicted in Fig. 1B) were evaluated for function and loosely grouped into categories based on their Entrez description. Genes within each category are listed alphabetically along the perimeter of the circle and marked by gray rectangles. Colored lines link a receptor (represented by the same colored rectangle) to the genes that it regulates. Genes repressed by WT-TRα1 are contacted by a green line, those repressed by rc6-TRα1 are contacted by a blue line, and those repressed by hcI-TRα1 are contacted by an orange line. Thin lines represent genes that met a BH-adjusted P value of at least <0.05; thick lines represent genes that met a BH-adjusted P value of <0.005. Genes contacted by multiple lines are repressed by multiple receptors. The diagram, exclusive of gene categorizations, was created using the open-source software package, Circos.

We conclude that the RCCC-TR and HCC-TR mutants possess distinct repertoires that may reflect tissue-specific differences in the mechanisms by which these TR mutants participate in neoplastic transformation. Consistent with this concept, v-Erb A, a TR mutant associated with erythroleukemias, displays yet a third pattern of gene regulation when expressed in cultured hepatocytes (63). Nonetheless, an additional, very limited set of genes appear to be targeted in common by TR mutants isolated from different neoplasia. Future analysis will be required to define whether these common targets represent a “core” mechanism of TR-mediated oncogenesis that is operative in multiple cancers.

A dominant-negative mutant TR associated with RTH retains the ability to repress certain WT-TRβ1 targets and unexpectedly gains the ability to regulate other genes not recognized by the WT receptor

Both the TR mutants associated with neoplasia and those associated with RTH-syndrome can behave as dominant-negative inhibitors, yet only the former contain mutations within their DNA recognition domains. We therefore tested whether a representative RTH-TRβ1 mutant regulated the same target gene repertoire as that of WT-TRβ1 (although presumably attenuated for activation), or whether the RTH-mutant manifested target gene-specific changes in its function. As anticipated from reporter gene assays, the RTH-TR mutant was able to repress (or unable to activate) several genes that were WT-TR targets. Unexpectedly, however, the RTH mutant also acquired an ability to activate genes not regulated by the WT-TRs. The P453S substitution in the RTH-TR mutant maps to the pivot between helix 11 and helix 12, an important determinant of corepressor release and coactivator recruitment. It is possible that this region plays an unanticipated role in target gene binding. Alternatively, the WT and P453S TR may bind to a common set of target genes but differ in their ability to repress or activate a given gene once bound. Whatever the mechanism, our results suggest that the clinical symptoms of RTH syndrome, rather than representing a simple global inhibition of WT-TR function, may instead represent a misregulation of specific subsets of target genes, the identity of which may vary for different RTH-TR mutants.

Materials and Methods

Generation of HepG2 stable transformants

The HepG2 stable transformants used for our analyses were generated previously (11). Briefly, TR mutations first identified in human RCCC or HCC cancers (24, 25) were introduced into a pCI-TR/neomycin expression vector using QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and were transformed into HepG2 cells. G418-resistant colonies were isolated and screened for TR integration and expression by RT-PCR. Twelve or more positive cell clones for each RCCC receptor were pooled to reduce the risk of possible clonal variation and treated with ± 100 nm T3 for 6 h; this concentration was chosen to be near saturating for all the mutant and WT-TRs tested, with the 6-h period short enough to confine the response primarily to direct targets of TR action. The RCCC- and WT-TRs were expressed at comparable levels by qRT-PCR, whereas the HCC-TRs were expressed at lower levels (Supplemental Fig. 1C); nonetheless, the expression levels of the HCC-TRs were sufficient to inhibit endogenous TR function in these cells and to mediate a pattern of target gene regulation readily distinguished from that of vector alone, and comparable in total number of gene targets to that seen with the more strongly expressed WT-TRs (e.g. Figure 3D and data not shown). Three biological replicates were performed for each TR allele and the empty vector control; all transformants were treated, and RNA was harvested and purified, in parallel. Gene expression analysis was performed using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST microarray (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA). The raw microarray data were normalized by the Robust Multichip Array method, with P value adjustments performed by the BH method using R software and the affylmGUI package. Details, and documentation of the validity of this overall approach, have been previously described (11, 64). RTH-TRβ1 transformants were created as described above.

Microarray analysis, statistics, and Circos gene expression diagram

Microarray expression data were normalized and analyzed as described previously (11). Two-step analyses of overlapping gene sets employed the BH adjusted P value to minimize false discovery rate, followed by comparisons between target gene sets using an unadjusted P value to indicate probability of coregulation. Under this criterion, genes that met an unadjusted P < 0.05 cut off were considered likely to be regulated. This less restrictive approach allowed us to identify additional genes that might be overlooked by a simple BH analyses. Use of the BH-adjusted P value to select our initial set of genes for the two-step analysis minimized possible false positives. Comprehensive gene expression diagrams were created using the free software package, Circos (65) and online supporting literature and tutorials (http://mkweb.bcgsc.ca/circos/tutorials/lessons/).

qRT-PCR

The RNA from our stable HepG2 cell lines was isolated and used for cDNA synthesis as described previously (11). qRT-PCR was performed with gene-specific primers designed using NCBI/Primer-Blast, and employing Bio-Rad's Ssofast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) with the manufacturer's suggested protocol. Primer sequences are presented in Supplemental Table 3. Primer sets for BICC1, GNG12, HEPACAM, PROM1, and PTAFR were previously described (11). Reactions were run on a DNA Engine Opticon 2 Continuous Fluorescence Detector (MJ Research, Inc, Waltham, MA) and analyzed using Opticon Monitor 3 software. Fold change refers to the cycle at which fluorescence crosses the set threshold, relative to vector-only control value.

Transient transfection assays

HepG2 stable cell lines expressing specific TR alleles were assayed for the ability to regulate an artificial DR4 reporter construct by transient transfection, using a DR4 thymidine-kinase promoter luciferase reporter (39). A lacZ construct was cointroduced as an internal transfection standard. Reporter assays were performed a minimum of three times, with the mean and standard error presented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Liming Liu (University of California at Davis) for technical support and Michael L. Goodson (University of California at Davis) for valuable advice and assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service/National Cancer Institute award R37-CA53394. I. H. C. was supported, in part, by a Public Health Service predoctoral training award, T32-GM007377, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Current address for I.H.C.: Merck & Co., San Francisco, California.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

NURSA Molecule pages†:

Nuclear Receptors: TR-α | TR-β;

Ligands: Thyroid hormone.

Annotations provided by Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas (NURSA) Bioinformatics Resource. Molecule Pages can be accessed on the NURSA website at www.nursa.org.

- BH

- Benjamini-Hochberg

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- HCC

- human hepatocellular carcinoma

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- RCCC

- renal clear cell carcinoma

- RTH

- resistance to thyroid hormone

- TR

- thyroid hormone receptor

- VHL

- von Hippel-Lindau

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Katz RW, Koenig RJ. 1993. Nonbiased identification of DNA sequences that bind thyroid hormone receptor α 1 with high affinity. J Biol Chem 268:19392–19397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazar MA. 1993. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev 14:184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lazar MA. 2003. Thyroid hormone action: a binding contract. J Clin Invest 112:497–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yen PM. 2001. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev 81:1097–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng SY. 2000. Multiple mechanisms for regulation of the transcriptional activity of thyroid hormone receptors. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 1:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang J, Lazar MA. 2000. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol 62:439–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harvey CB, Williams GR. 2002. Mechanism of thyroid hormone action. Thyroid 12:441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hollenberg AN, Monden T, Flynn TR, Boers ME, Cohen O, Wondisford FE. 1995. The human thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene is regulated by thyroid hormone through two distinct classes of negative thyroid hormone response elements. Mol Endocrinol 9:540–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nygård M, Wahlström GM, Gustafsson MV, Tokumoto YM, Bondesson M. 2003. Hormone-dependent repression of the E2F-1 gene by thyroid hormone receptors. Mol Endocrinol 17:79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Decherf S, Seugnet I, Kouidhi S, Lopez-Juarez A, Clerget-Froidevaux MS, Demeneix BA. 2010. Thyroid hormone exerts negative feedback on hypothalamic type 4 melanocortin receptor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4471–4476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan IH, Privalsky ML. 2009. Thyroid hormone receptor mutants implicated in human hepatocellular carcinoma display an altered target gene repertoire. Oncogene 28:4162–4174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aranda A, Pascual A. 2001. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiol Rev 81:1269–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JW, Lee YC, Na SY, Jung DJ, Lee SK. 2001. Transcriptional coregulators of the nuclear receptor superfamily: coactivators and corepressors. Cell Mol Life Sci 58:289–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones PL, Shi YB. 2003. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 274:237–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Privalsky ML. 2004. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol 66:315–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forrest D, Erway LC, Ng L, Altschuler R, Curran T. 1996. Thyroid hormone receptor beta is essential for development of auditory function. Nat Genet 13:354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wikström L, Johansson C, Saltó C, Barlow C, Campos Barros A, Baas F, Forrest D, Thorén P, Vennström B. 1998. Abnormal heart rate and body temperature in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor α 1. EMBO J 17:455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ng L, Hurley JB, Dierks B, Srinivas M, Saltó C, Vennström B, Reh TA, Forrest D. 2001. A thyroid hormone receptor that is required for the development of green cone photoreceptors. Nat Genet 27:94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oetting A, Yen PM. 2007. New insights into thyroid hormone action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 21:193–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. 2010. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev 31:139–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. García-Silva S, Aranda A. 2004. The thyroid hormone receptor is a suppressor of ras-mediated transcription, proliferation, and transformation. Mol Cell Biol 24:7514–7523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martínez-Iglesias O, Garcia-Silva S, Tenbaum SP, Regadera J, Larcher F, Paramio JM, Vennström B, Aranda A. 2009. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 acts as a potent suppressor of tumor invasiveness and metastasis. Cancer Res 69:501–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhu XG, Zhao L, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. 2010. Thyroid hormone receptors are tumor suppressors in a mouse model of metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma. Oncogene 29:1909–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin KH, Shieh HY, Chen SL, Hsu HC. 1999. Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog 26:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamiya Y, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, McPhie P, Nauman J, Cheng SY, Nauman A. 2002. Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors is associated with human renal clear cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 23:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Krystyniak A, Madej A, Cheng SY, Nauman J. 2002. Functionally impaired TR mutants are present in thyroid papillary cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1120–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang CS, Lin KH, Hsu YC. 2002. Alterations of thyroid hormone receptor α gene: frequency and association with Nm23 protein expression and metastasis in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 175:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cheng SY. 2003. Thyroid hormone receptor mutations in cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 213:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vennström B, Bishop JM. 1982. Isolation and characterization of chicken DNA homologous to the two putative oncogenes of avian erythroblastosis virus. Cell 28:135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Graf T, Beug H. 1983. Role of the v-erbA and v-erbB oncogenes of avian erythroblastosis virus in erythroid cell transformation. Cell 34:7–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sap J, Muñoz A, Damm K, Goldberg Y, Ghysdael J, Leutz A, Beug H, Vennström B. 1986. The c-erb-A protein is a high-affinity receptor for thyroid hormone. Nature 324:635–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weinberger C, Thompson CC, Ong ES, Lebo R, Gruol DJ, Evans RM. 1986. The c-erb-A gene encodes a thyroid hormone receptor. Nature 324:641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kahn P, Frykberg L, Brady C, Stanley I, Beug H, Vennström B, Graf T. 1986. v-erbA cooperates with sarcoma oncogenes in leukemic cell transformation. Cell 45:349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Damm K, Thompson CC, Evans RM. 1989. Protein encoded by v-erbA functions as a thyroid-hormone receptor antagonist. Nature 339:593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Privalsky ML. 1992. v-erb A, nuclear hormone receptors, and oncogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1114:51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Refetoff S, Weiss RE, Usala SJ. 1993. The syndromes of resistance to thyroid hormone. Endocr Rev 14:348–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kopp P, Kitajima K, Jameson JL. 1996. Syndrome of resistance to thyroid hormone: insights into thyroid hormone action. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 211:49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yen PM. 2003. Molecular basis of resistance to thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrinol Metab 14:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan IH, Privalsky ML. 2006. Thyroid hormone receptors mutated in liver cancer function as distorted antimorphs. Oncogene 25:3576–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Darby IA, Bouhnik J, Coezy ED, Corvol P. 1991. Thyroid hormone receptors and stimulation of angiotensinogen production in HepG2 cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 27:21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nozaki S, Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Menju M, Kubo M, Matsuzawa Y. 1992. Stimulation of the activity and mRNA level of hepatic triacylglycerol lipase by triiodothyronine in HepG2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1127:298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Theriault A, Ogbonna G, Adeli K. 1992. Thyroid hormone modulates apolipoprotein B gene expression in HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 186:617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chamba A, Neuberger J, Strain A, Hopkins J, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. 1996. Expression and function of thyroid hormone receptor variants in normal and chronically diseased human liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:360–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin KH, Zhu XG, Shieh HY, Hsu HC, Chen ST, McPhie P, Cheng SY. 1996. Identification of naturally occurring dominant negative mutants of thyroid hormone α 1 and β 1 receptors in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Endocrinology 137:4073–4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rosen MD, Privalsky ML. 2009. Thyroid hormone receptor mutations found in renal clear cell carcinomas alter corepressor release and reveal helix 12 as key determinant of corepressor specificity. Mol Endocrinol 23:1183–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wan W, Farboud B, Privalsky ML. 2005. Pituitary resistance to thyroid hormone syndrome is associated with T3 receptor mutants that selectively impair β2 isoform function. Mol Endocrinol 19:1529–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Refetoff S, Weiss RE, Wing JR, Sarne D, Chyna B, Hayashi Y. 1994. Resistance to thyroid hormone in subjects from two unrelated families is associated with a point mutation in the thyroid hormone receptor β gene resulting in the replacement of the normal proline 453 with serine. Thyroid 4:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin BC, Hong SH, Krig S, Yoh SM, Privalsky ML. 1997. A conformational switch in nuclear hormone receptors is involved in coupling hormone binding to corepressor release. Mol Cell Biol 17:6131–6138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee S, Privalsky ML. 2005. Multiple mutations contribute to repression by the v-Erb A oncoprotein. Oncogene 24:6737–6752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Takahashi M, Teh BT, Kanayama HO. 2006. Elucidation of the molecular signatures of renal cell carcinoma by gene expression profiling. J Med Invest 53:9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, Teague J, Andrews J, Barthorpe S, Beare D, Buck G, Campbell PJ, Forbes S, Jia M, Jones D, Knott H, Kok CY, Lau KW, Leroy C, Lin ML, McBride DJ, et al. 2010. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature 463:360–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Takahashi M, Yang XJ, Sugimura J, Backdahl J, Tretiakova M, Qian CN, Gray SG, Knapp R, Anema J, Kahnoski R, Nicol D, Vogelzang NJ, Furge KA, Kanayama H, Kagawa S, Teh BT. 2003. Molecular subclassification of kidney tumors and the discovery of new diagnostic markers. Oncogene 22:6810–6818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L. 1993. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 260:1317–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. 1999. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stebbins CE, Kaelin WG, Jr, Pavletich NP. 1999. Structure of the VHL-ElonginC-ElonginB complex: implications for VHL tumor suppressor function. Science 284:455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Linehan WM, Rubin JS, Bottaro DP. 2009. VHL loss of function and its impact on oncogenic signaling networks in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41:753–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G, Pinto PA, Schmidt LS, Neckers L, Bottaro DP, Srinivasan R. 2010. Molecular diagnosis and therapy of kidney cancer. Annu Rev Med 61:329–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wick M, Bürger C, Funk M, Müller R. 1995. Identification of a novel mitogen-inducible gene (mig-6): regulation during G1 progression and differentiation. Exp Cell Res 219:527–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lin KR, Lee SF, Hung CM, Li CL, Yang-Yen HF, Yen JJ. 2007. Survival factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis of TF-1 cells involves a TRB2-Mcl-1 axis-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 282:21962–21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Datta J, Majumder S, Kutay H, Motiwala T, Frankel W, Costa R, Cha HC, MacDougald OA, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K. 2007. Metallothionein expression is suppressed in primary human hepatocellular carcinomas and is mediated through inactivation of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling cascade. Cancer Res 67:2736–2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tao X, Zheng JM, Xu AM, Chen XF, Zhang SH. 2007. Down-regulated expression of metallothionein and its clinicopathological significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 37:820–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kanda M, Nomoto S, Okamura Y, Nishikawa Y, Sugimoto H, Kanazumi N, Takeda S, Nakao A. 2009. Detection of metallothionein 1G as a methylated tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel method of double combination array analysis. Int J Oncol 35:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ventura-Holman T, Mamoon A, Subauste JS. 2008. Modulation of expression of RA-regulated genes by the oncoprotein verbA. Gene 425:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chan IH, Privalsky ML. 2009. Isoform-specific transcriptional activity of overlapping target genes that respond to thyroid hormone receptors α1 and β1. Mol Endocrinol 23:1758–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. 2009. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 19:1639–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.