Abstract

Expression of nifH in 28 surface water samples collected during fall 2007 from six stations in the vicinity of the Cape Verde Islands (north-east Atlantic) was examined using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-based clone libraries and quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of seven diazotrophic phylotypes. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) rates and nutrient concentrations were determined for these stations, which were selected based on a range in surface chlorophyll concentrations to target a gradient of primary productivity. BNF rates greater than 6 nmolN l−1 h−1 were measured at two of the near-shore stations where high concentrations of Fe and PO43− were also measured. Six hundred and five nifH transcripts were amplified by RT-PCR, of which 76% are described by six operational taxonomic units, including Trichodesmium and the uncultivated UCYN-A, and four non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs that clustered with uncultivated Proteobacteria. Although all five cyanobacterial phylotypes quantified in RT-qPCR assays were detected at different stations in this study, UCYN-A contributed most significantly to the pool of nifH transcripts in both coastal and oligotrophic waters. A comparison of results from RT-PCR clone libraries and RT-qPCR indicated that a γ-proteobacterial phylotype was preferentially amplified in clone libraries, which underscores the need to use caution interpreting clone-library-based nifH studies, especially when considering the importance of uncultivated proteobacterial diazotrophs.

Keywords: nitrogen fixation, nifH, nitrogenase, molecular, Cape Verde, Atlantic

Introduction

Nitrogen is often a limiting nutrient in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, including the open ocean (Vitousek and Howarth, 1991). Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), the reduction of atmospheric N2 to biologically available ammonium, is an important source of N for oligotrophic oceans (Gruber and Sarmiento, 1997; Karl et al., 1997; Mahaffey et al., 2005). BNF is performed by a limited, but diverse, group of microorganisms known as diazotrophs (Zehr et al., 2003b; Zehr and Paerl, 2008). For many years, BNF in the oceans was believed to be due to Trichodesmium, a filamentous, aggregate-forming, non-heterocystous cyanobacterium, and Richelia, the heterocystous symbiont of diatoms (LaRoche and Breitbarth, 2005; Mahaffey et al., 2005), until the discovery of unicellular diazotrophic Cyanobacteria (Zehr et al., 2001; Montoya et al., 2004). These microorganisms were discovered by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the nifH gene, which encodes the iron protein of nitrogenase, the enzyme that catalyzes N2 fixation, as they are small, low in abundance and unidentifiable as diazotrophs using microscopy or 16S rRNA gene sequences. Non-cyanobacterial N2-fixing microorganisms have also been detected with PCR (Zehr et al., 2001; Bird et al., 2005), but their significance in marine BNF is not well understood. Relatively little is known about the distribution of diazotrophs (Falcón et al., 2002; Langlois et al., 2005, 2008; Foster et al., 2007, 2009b; Hewson et al., 2007; Church et al., 2008; Moisander et al., 2010), or the factors that control their distribution and activity (Berman-Frank et al., 2007; Moisander et al., 2010).

The nitrogenase proteins require iron (reviewed by Kustka et al. (2002)), and the availability of both phosphorus and iron are factors that may be important in limiting or co-limiting BNF (Sanudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2001; Karl et al., 2002; Mills et al., 2004) in some areas of the world's oceans. It is clear that no one factor controls marine BNF rates and that nitrogenase activity is determined by a combination of variables that differ depending on the geographic region and diazotroph community composition (Mahaffey et al., 2005). This study focused on BNF rates and nifH expression near the Cape Verde Islands, in the eastern North Atlantic, and was performed as part of the UK SOLAS-funded INSPIRE cruise (D325). This is a unique study area as nutrient concentrations are generally depleted, but can be influenced by local upwelling effects associated with the islands. This region is also strongly influenced by Saharan dust deposition (Chiapello et al., 1995), which supplies both iron and phosphorus to surface waters (Mills et al., 2004; LaRoche and Breitbarth, 2005). Previous studies in the North Atlantic and the equatorial North Atlantic have documented the presence of diverse N2-fixing Cyanobacteria and bacteria (Langlois et al., 2005, 2008; Goebel et al., 2010). This study focused on describing the diversity of nifH-containing organisms actively transcribing nifH via reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, quantifying the number of nifH transcripts from seven major cyanobacterial and non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs using quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR), and measuring BNF rates along with physical and chemical parameters in this region. It is hypothesized that BNF rates will correlate both to Fe concentrations and to the magnitude of nifH expression of some or all the diazotrophs assayed using qPCR.

Experimental procedures

Sample collection

Surface seawater samples were collected in a trace metal clean laboratory with a ‘towed torpedo fish' system using a Teflon diaphragm pump (Almatec A-15, Kamp-Lintfort, Germany) from six oceanographic stations during November–December 2007 (Table 1). The site selection was guided by processed surface ocean color satellite images supplied daily by the UK Natural Environment Research Council Earth Observation Data Acquisition and Analysis Service (http://www.neodaas.ac.uk/) at Plymouth Marine Laboratory. Six sites were chosen to give a gradient of conditions from near-shore coastal waters off Cape Verde Islands (Stations B and C), immediately offshore waters (Stations A and D) and open, oligotrophic waters (Stations E and F). At Stations C–F, a six-point time series was collected over a 20-h period to assess diel variability of nifH expression. This diel cycle was sampled under a Lagrangian framework (following the same parcel of seawater) using a free-floating drifter buoy, which was deployed at a depth of 15 m. For each sample, 10 l of seawater was filtered using a peristaltic pump through a 0.22-μm Sterivex filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which was stored at −80 °C until nucleic acid extraction. Filtration time did not exceed 30 min.

Table 1. Environmental conditions and nifH RT-qPCR results at Cape Verde sampling stations.

| Sample | Station | Lat. (°N) | Long. (°W) | Date (dd.mm.yy) | Time (hh:mm) | Temp ( °C) | Salinity (Psu) | BNF rate (nmolN l−1 h−1) | Nitrate+ nitrite (μ) | PO43− (μ) | Iron (n) | Chl a (μg l−1) | nifH transcripts per l |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCYN-A | UCYN-B | Tricho. | RR | HR | γ-prot | α-prot | |||||||||||||

| 1 | A | 17.72 | −22.74 | 17.11.07 | 4:09 | 24.9 | 36.8 | 6.3 | <0.02 | 0.05 | 1.51 | 0.1 | 1.3E+05 | DNQ | UD | 8.8E+02 | UD | UD | UD |

| 2 | B | 16.89 | −24.83 | 22.11.07 | 4:34 | 25.3 | 36.7 | 6.0 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 1.0E+04 | UD | 4.9E+03 | UD | UD | UD | UD |

| 3 | B | 16.89 | −24.83 | 22.11.07 | 13:53 | 25.2 | 36.8 | 6.0 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 1.4E+03 | UD | UD | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | UD | |

| 4* | B | 16.89 | −24.83 | 22.11.07 | 13:53 | 25.2 | 36.8 | 6.0 | 4.12 | 0.33 | 1.9E+03 | DNQ | 5.2E+02 | UD | 2.2E+03 | UD | UD | ||

| 5 | C | 16.01 | −23.66 | 28.11.07 | 6:50 | 24.9 | 36.8 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.19 | UD | UD | 6.3E+02 | DNQ | 8.6E+02 | UD | UD |

| 6 | C | 16.02 | −23.73 | 28.11.07 | 6:45 | 24.7 | 36.5 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.22 | UD | UD | 9.0E+02 | DNQ | 1.1E+03 | UD | UD | |

| 7 | C | 16.02 | −23.74 | 28.11.07 | 10:15 | 24.7 | 36.5 | 0.3 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.32 | UD | UD | 2.5E+03 | DNQ | 1.0E+03 | UD | UD | |

| 8 | C | 16.03 | −23.76 | 28.11.07 | 14:10 | 24.7 | 36.4 | 0.4 | 0.053 | 0.04 | UD | UD | UD | UD | ND | UD | UD | ||

| 9 | C | 16.04 | −23.78 | 28.11.07 | 18:15 | 24.7 | 36.5 | 0.5 | 0.053 | 0.04 | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | ND | UD | UD | ||

| 10 | C | 16.03 | −23.78 | 28.11.07 | 23:35 | 24.7 | 36.5 | 0.2 | 0.053 | 0.04 | UD | UD | UD | ND | ND | UD | UD | ||

| 11 | C | 16.02 | −23.77 | 28.11.07 | 2:00 | 24.6 | 36.5 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.04 | UD | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | UD | UD | ||

| 12 | D | 17.72 | −22.95 | 02.12.07 | 6:15 | 23.9 | 36.8 | 0.1 | <0.02 | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 4.1E+04 | UD | UD | DNQ | ND | DNQ | UD |

| 13 | D | 17.78 | −22.96 | 02.12.07 | 10:10 | 23.9 | 36.8 | 0.3 | <0.02 | 0.12 | 7.3E+04 | 1.5E+03 | DNQ | DNQ | UD | DNQ | UD | ||

| 14 | D | 17.79 | −22.97 | 02.12.07 | 14:15 | 24 | 36.8 | 0.2 | <0.02 | 0.12 | 1.6E+04 | UD | UD | ND | ND | DNQ | UD | ||

| 15 | D | 17.80 | −23.00 | 02.12.07 | 18:15 | 24 | 36.8 | 0.3 | <0.02 | 0.12 | DNQ | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | UD | UD | ||

| 16 | D | 17.81 | −23.05 | 02.12.07 | 23:05 | 24 | 36.9 | 0.2 | <0.02 | 0.12 | 4.5E+03 | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | UD | UD | ||

| 17 | D | 17.81 | −23.09 | 03.12.07 | 2:30 | 23.9 | 36.9 | 0.1 | <0.02 | 0.14 | DNQ | UD | UD | 1.0E+03 | UD | UD | UD | ||

| 18 | E | 20.65 | −24.96 | 07.12.07 | 5:30 | 23.9 | 36.9 | 0.1 | <0.02 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 7.6E+04 | UD | DNQ | UD | UD | DNQ | UD |

| 19 | E | 20.85 | −25.01 | 07.12.07 | 6:25 | 23.9 | 37.0 | 0.1 | <0.02 | 0.05 | 4.5E+04 | UD | 9.5E+02 | DNQ | UD | 8.1E+03 | UD | ||

| 21 | E | 20.94 | −25.04 | 07.12.07 | 14:00 | 23.9 | 36.9 | 0.3 | <0.02 | 0.05 | 2.4E+04 | UD | DNQ | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | ||

| 22 | E | 20.98 | −25.05 | 07.12.07 | 18:25 | 23.9 | 36.9 | 0.1 | <0.02 | 0.05 | 3.4E+03 | DNQ | UD | UD | UD | 8.7E+03 | UD | ||

| 23 | E | 21.04 | −25.05 | 07.12.07 | 22:55 | 23.8 | 36.9 | ND | <0.02 | 0.05 | 4.4E+04 | UD | UD | DNQ | UD | DNQ | UD | ||

| 24 | E | 21.08 | −25.05 | 08.12.07 | 1:55 | 23.8 | 36.9 | ND | <0.02 | 0.05 | 1.2E+05 | UD | UD | UD | UD | UD | UD | ||

| 25 | F | 26.05 | −23.99 | 12.12.07 | 6:15 | 23.3 | 37.4 | bdl | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.54 | 0.06 | DNQ | UD | DNQ | DNQ | ND | DNQ | UD |

| 26 | F | 26.05 | −23.98 | 12.12.07 | 10:15 | 22.7 | 37.3 | 0.1 | <0.02 | <0.02 | DNQ | UD | 1.2E+03 | 1.6E+03 | DNQ | DNQ | UD | ||

| 27 | F | 26.07 | −23.99 | 12.12.07 | 14:15 | 22.9 | 37.3 | 0.1 | <0.02 | <0.02 | UD | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | UD | ||

| 28 | F | 26.09 | −24.01 | 12.12.07 | 18:20 | 22.7 | 37.3 | 0.1 | <0.02 | <0.02 | DNQ | 1.4E+03 | DNQ | DNQ | 1.5E+03 | 6.8E+03 | UD | ||

| 29 | F | 26.08 | −24.00 | 12.12.07 | 23:10 | 22.6 | 37.3 | 0.1 | <0.02 | <0.02 | DNQ | UD | UD | 9.5E+02 | DNQ | UD | UD | ||

| 30 | F | 26.10 | −23.99 | 13.12.07 | 2:30 | 22.6 | 37.3 | bdl | <0.02 | <0.02 | 6.8E+02 | UD | DNQ | 3.2E+03 | DNQ | DNQ | UD | ||

Abbreviations: α-prot, α-24809A06; bdl, below detection limit; BNF, biological nitrogen fixation; DNQ, detected not quantified; γ-prot, γ-24774A11; HR, Richelia in Hemiaulus; ND, no data; RR, Richelia in Rhizosolenia; RT-qPCR, quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; UD, undetected.

Sites are divided into Stations A–F, grouped by similar latitude and longitudes. Diel sampling occurred at Stations C–F. All samples were taken within the mix layer, thus considered to be surface or near-surface samples, with the exception of B4 (marked with an asterisk), which was sampled at 50 m.

N2 fixation rates

Surface seawater samples, obtained using the Royal Research Ship Discovery's seawater pump, were distributed into triplicate 1-l polycarbonate bottles and 2 ml of 15N-N2 was added. Bottles were transferred to on-deck incubators, maintained at sea surface temperature, and incubated without light-attenuating filters for 6 h. Six-hour incubations were chosen to provide a gross BNF rate throughout a diel cycle and correspond with samples collected for molecular analysis. Experiments were terminated by filtration onto 25-mm GF/F filters (Millipore), which were dried at 50 °C for 12 h and stored over silica gel desiccant until return to Plymouth Marine Laboratory. Particulate nitrogen and 15N atom% were measured using continuous-flow stable isotope mass spectrometry (PDZ-Europa 20-20 and GSL; Owens and Rees, 1989), with rates and 15N enrichment determined according to Montoya et al. (1996). Background 15N content of particulate material was determined from unamended 1-l aliquots of seawater filtered immediately upon collection.

Dissolved iron analysis

Samples for dissolved iron were collected using the ‘towed torpedo fish' approach described above. Seawater was filtered through acid-cleaned 0.2-μm polycarbonate track-etched membrane filters (Nucleopore; Millipore) held in a PTFE Teflon filter holder. Filtrate was collected in 125-ml acid-cleaned low-density polyethylene bottles and acidified to pH 1.7 using UHP HCl (SpA; Romil, UK). All operations were carried out in clean room conditions under a class 100 laminar-flow hood.

Total dissolved iron was determined using flow injection with chemiluminescence detection (FI-CL) as described by de Jong et al. (1998), with modifications described in de Baar et al. (2008). Stock standard solutions were prepared in acidified UHP water from an iron atomic absorption standard solution (Spectrosol, UK). Working standards (0.125–1.5 n) were prepared in acidified low trace metal seawater and used in daily calibrations. The analytical detection limit was 0.08 n (n=8).

Nutrient and chlorophyll a analysis

Samples collected for the analysis of NO2−, NO3− and PO43− were analyzed within 2 h of collection. PO43− was determined according to Kirkwood (1989), and NO2− and NO3− were measured with a segmented flow colorimetric auto-analyzer according to Brewer and Riley (1965) for nitrate and Grasshoff et al. (1999) for nitrite. The detection limit was 20 n for all three nutrients and the precision was better than ±10 n. Chlorophyll a was determined on acetone extractions using a Turner fluorometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to Welschmeyer (1994).

RNA extraction and cDNA generation

The phenol/chloroform Sterivex extraction method of Neufeld et al. (2007) was used to extract total nucleic acids. After extraction, RNA was isolated and DNA was removed using the RNA-Easy mini prep kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and Turbo-DNA free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) following the manufacturer's guidelines. RNA purity and integrity was checked using an RNA6000 chip on an Agilent Bioanalyser. cDNA was synthesized for RT-PCR by RT of purified RNA using the SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System for RT-qPCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's guidelines, using 10 ng purified RNA extract and 0.5 μ of nifH3 reverse primer (Zani et al., 2000). Negative controls (no-RTs) were generated for each sample.

For RT-qPCR analysis, cDNA was generated directly from the total nucleic acid extract using the protocol described above, after DNA removal using amplification grade DNaseI (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Negative controls were processed for a subset of samples to confirm complete degradation of DNA. An additional modification in cDNA generation for RT-qPCR was the use of equimolar quantities (0.25 μ) of nifH2 (Zehr and McReynolds, 1989) and nifH3 primers.

RT-PCR

The first round of nifH amplification proceeded as follows: 1 μl of cDNA was added to a 24 μl PCR reaction containing 4 m MgCl2, 1X GoTaq buffer, 0.2 m dNTPs, 2 pmol primers (nifH3 and nifH4) (Zani et al., 2000) and 1.25 U of Taq (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The reaction was performed with 35 cycles of 95 °C (1 min), 55 °C (1 min) and 72 °C (1 min). The second amplification used 1 μl of the first-round PCR product, the primers nifH1 and nifH2 (Zehr and McReynolds, 1989) and reaction conditions identical to the first round. PCR products were twice gel purified with a Wizard SV Gel Clean-Up System kit (Promega). The purified PCR products were cloned using the pGem-T Easy vector kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's guidelines. Random inserts were sequenced from the 28 samples using M13 primers (ABI BigDye 3.1 used at one-eighth reaction). This sequence data has been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers HQ611353–HQ611956.

RT-qPCR

Expression of nifH from five different cyanobacterial and two proteobacterial phylotypes was quantified using TaqMan RT-qPCR assays (Table 2). All qPCR reactions were set up as described in Moisander et al. (2010) using undiluted cDNA, and only 1 μl template in Richelia in Rhizosolenia (RR) and Richelia in Hemaulus (HR) assays. In 96-well reaction plates, each RT and no-RT reaction were run in duplicate, along with a minimum of two no-template controls and a standard curve (100–107 nifH copies per reaction) generated with linearized recombinant plasmids with the appropriate target (Table 2).

Table 2. qPCR primers and probes used in this study.

| Phylotype target | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Probe (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | GenBank accesion no. of standard | Efficiency (E) | LOD (nifH transcripts per l) | LOQ (nifH transcripts per l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCYN-A (Church et al., 2005a) | AGCTATAACAACGTTTTATGCGTTGA | TCTGGTGGTCCTGAGCCTGGA | ACCACGACCAGCACATCCA | AF059642 | 104±3% | 72 | 576 |

| UCYN-B (Moisander et al., 2010) | CGTAATGCTCGAAGGGTTTGA | CAAGTGTGTAGAATCTGGTGGTCCTGAGCC | CACGACCAGCACAACCAACT | DQ481411 | 96±3% | 72 | 576 |

| Trichodesmium (Church et al., 2005a) | GACGAAGTATTGAAGCCAGGTTTC | CATTAAGTGTGTTGAATCTGGTGGTCCTGAGC | CGGCCAGCGCAACCTA | DQ404414 | 98±3% | 72 | 576 |

| Richelia associated with R. clevi (RR) (Church et al., 2005b) | CGGTTTCCGTGGTGTACGTT | TCCGGTGGTCCTGAGCCTGGTGT | AATACCACGACCCGCACAAC | DQ225757 | 97±2% | 144 | 1150 |

| Richelia associated with H. haukii (HR) (Foster et al., 2007) | TGGTTACCGTGATGTACGTT | TCTGGTGGTCCTGAGCCTGGTGT | AATGCCGCGACCAGCACAAC | DQ225753 | 101±1% | 144 | 1150 |

| γ-Proteobacteria (γ-24774A11) (Moisander et al., 2010)a | CGGTAGAGGATCTTGAGCTTGAA | AAGTGCTTAAGGTTGGCTTTGGCGACA | CACCTGACTCCACGCACTTG | EU052413 | 98±6% | 72 | 576 |

| α-Proteobacteria (α-24809A06)a (Moisander et al., 2010)a | TCTGATCCTGAACTCCAAAGCA | ACCGTGCTGCACCTGGCCG | TCCTCAACCGAACCCATTTC | EU052488 | 104±1% | 72 | 576 |

Abbreviations: LOD, limit of detection; LOQ, limit of quantitation; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; RT, reverse transcription.

The oligonucleotide sequence for the reverse primer has an error in the original reference. LOD and LOQs are determined by considering dilutions made during the RT reactions, volume of extract used in RT-qPCR reactions, nucleic acid extraction volumes and volume of seawater filtered.

Amplifications were carried out using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real time PCR system and the 7500 System SDS software using the thermocycling method described in Moisander et al. (2010). RTs and no-RTs were tested for inhibition as described in Goebel et al. (2010). No inhibition was observed in any of the 28 samples.

The limit of detection and limit of quantification have been determined to be 1 and 8 nifH copies per reaction, respectively (data not shown), and are reported as nifH transcripts per l in Table 2. Samples that amplified but fell below the limit of quantification were designated ‘detected not quantified (DNQ)'. The efficiency (E) of amplifications was determined using the formula E=10−1/m–1, where m is the slope from the regression described above (Table 2).

Linear regressions were used to determine whether correlations could be made between nifH expression, BNF rates and environmental parameters (Supplementary Table 1). If necessary, data were first transformed to meet conditions of normality and homoscedasticity.

Bioinformatic and phylogenetic analysis

Nucleic acid sequences were quality checked, trimmed and imported into a publically available nifH database (Zehr et al., 2003b) with >150 000 sequences from GenBank (http://www.es.ucsc.edu/~wwwzehr/research/database/) in the software program ARB (Ludwig et al., 2004). Translated amino acid sequences were aligned using a Hidden Markov Model from PFAM (Finn et al., 2010). Nucleotide sequences were re-aligned according to the aligned amino-acid sequences, and operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined using 91% similarity cutoff in DOTUR v1.53 (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005). Nearest neighbors for OTUs were determined using the parsimony quick add function in ARB. A neighbor-joining tree of partial nifH sequences was constructed in ARB and branch lengths were computed using the Jukes–Cantor correction. Bootstrapping (1000 replicates) was performed in MEGA 4.0.

Results and discussion

Nitrogen fixation rates and environmental variables

There was a gradient of surface water temperatures between stations nearest to the Cape Verde Islands and at lower latitudes (B/C) and stations farthest from the islands at higher latitudes (E/F) from 25.3 °C at Station B to 22.6 °C at Station F. Sea surface temperatures positively correlated with a gradient of chloroform a concentrations (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). Temperature–salinity plots (Supplementary Figure 1) show that the same water masses were sampled during diel samplings at Stations C–F using the drogue, with the exception of sample C5. NO3− concentrations were generally low, but ranged from below detection to over 0.12 μ at Station C. Dissolved iron concentrations were within the range reported in previous studies in this region (Sarthou et al., 2003; Rijkenberg et al., 2008), with the exception of Station A (1.5 n). Five-day air mass back trajectories, calculated by the HYPSPLIT transport and dispersion model (NOAA Air Resources Laboratory), showed the presence of dust over Station A, which was responsible for the high concentration of Fe. Fe and PO43− concentrations were replete relative to NO3−; thus, N:P ratios were low (<1.9), indicating potential N-limiting conditions consistent with Mills et al. (2004).

Stations A and B had the highest BNF rates measured during this study, at 6.3 and 6.0 nmolN l−1 h−1, respectively. Although rates of similar magnitude have been reported in the Eastern Mediterranean (5.3 nmolN l−1 h−1) (Rees et al., 2006), BNF rates at Stations A and B are relatively high in comparison to rates from the North Pacific (a region where Fe and P may also be limiting or co-limiting), which are generally less than 1.9 nmolN l−1 h−1 (Montoya et al., 2004; Zehr et al., 2007; Fong et al., 2008; Grabowski et al., 2008). Stations C–F had rates <1 nmolN l−1 h−1, which are comparable to rates reported in Fe- and P-amended waters 800 km south of Station C by Mills et al. (2004) and the temperate coastal waters of the English Channel (Rees et al., 2009).

The highest BNF rates measured in this study coincided with the highest measured dissolved Fe concentrations (1.51 and 0.58 n) (Table 1). Although both Fe and PO43− have been hypothesized to limit or co-limit N2 fixation in this region (Sanudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2001; Karl et al., 2002; Mills et al., 2004), linear regressions indicate that BNF had positive correlations to Fe (r2=0.63, P=0.05, n=6) and temperature (r2=0.37, P=0.001, n=25), but not to PO43− (Supplementary Table 1). None of the other environmental parameters measured could be correlated to BNF rates. These data confirm that dissolved Fe concentrations are an important factor in N2 fixation in this region.

It is important to note that a recent study by Mohr et al. (2010) has shown that the 15N-tracer method developed by Montoya et al. (1996) used here and widely throughout the scientific community may underestimate N2 fixation rates. Mohr et al. (2010) determined that bubble injections of 15N2 gas are slow to equilibrate using traditional shipboard incubation techniques, which has a significant impact on calculations used in determining BNF rates. As such, the timing of 15N2 injections relative to peak nitrogenase activity in diel studies can have a variable impact on measured BNF rates. It is unclear as to what extent our current understanding of global BNF rates will be altered as the community adopts the modified technique developed by Mohr et al. (2010) to address this underestimation.

nifH gene diversity (RT-PCR)

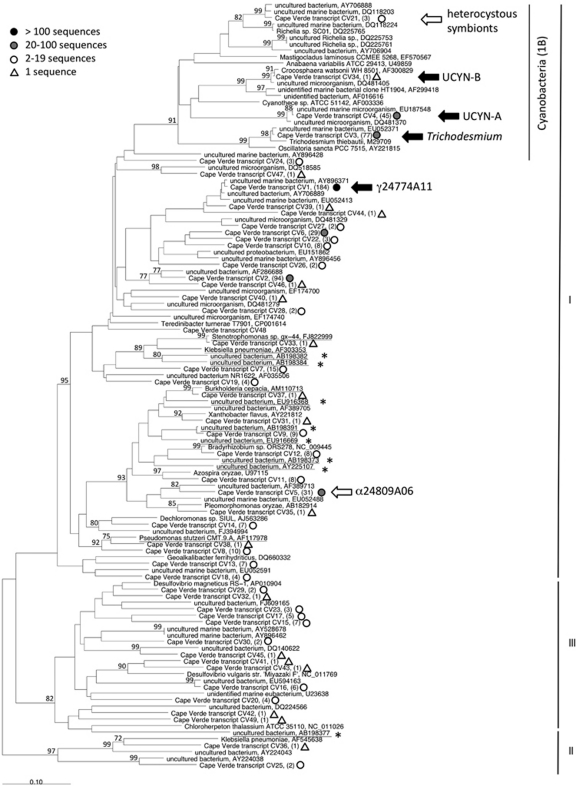

A total of 605 nifH transcript sequences were amplified from the 28 samples. Using cluster designations as in Zehr et al. (2003b), there were 567 Cluster I (93.7%), three Cluster II (0.5%) and 35 Cluster III (5.8%) nifH sequences. Forty-nine nifH OTUs were designated using a 91% nucleotide sequence similarity cutoff. The top six most highly recovered OTUs, which accounted for 76% of all transcripts, were Cluster I sequences; four were of proteobacterial origin, and two were of cyanobacterial origin (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1.

Neighbor-joining tree of partial nifH cyanobacterial sequences obtained from Cape Verde transcripts. Branch lengths were computed using the Jukes–Cantor correction in the ARB software. Bootstrapping was performed in MEGA 4.0, and bootstraps greater than 70% (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Cape Verde transcripts are marked according to the key to emphasize the number of sequences represented by each OTU. All Trichodesmium, UCYN-A, UCYN-B and γ-24774A11 transcript sequences are targeted by the qPCR assays used in this study. Sequences that are related, but not identical, to phylotypes that are targeted with qPCR assays are marked with a white arrow. Sequences that are suspected contaminants are underlined, and those that have been determined to be contaminants in nifH-based PCR studies are marked with an asterisk.

The most highly recovered OTU, CV1, accounted for 30.4% of all transcript sequences, and was amplified from all stations. CV1 clustered with uncultivated γ-proteobacterial sequences that have been widely reported in DNA-based studies (PCR and qPCR) from regions in the North Pacific (Church et al., 2005b; Fong et al., 2008), South Pacific (Moisander et al., 2010), Arabian Sea (Bird et al., 2005), South China Sea (Moisander et al., 2007), Equatorial Atlantic (Foster et al., 2009b), tropical Atlantic (Langlois et al., 2008) and in the Mediterranean Sea (Man-Aharonovich et al., 2007). It has also been reported actively expressing nifH in numerous studies (Bird et al., 2005; Church et al., 2005b; Man-Aharonovich et al., 2007). The γ-proteobacteria in all of these studies, as well as CV1, were targeted with the qPCR assay designed by Moisander et al. (2008) for γ-24774A11.

The second most highly recovered OTU, CV2 (15.5%), amplified from Stations C–F, also clustered with uncultivated γ-proteobacterial sequences, and has a high sequence similarity to environmental sequences from the English Channel (EF407529, EF407533 and EF407537) and the Amazon River Plume (DQ481447–DQ481449).

The third and fourth most highly recovered OTUs, CV3 and CV4, clustered with Cyanobacteria, and together accounted for 20% of the transcripts. CV3 (13%) clusters with Trichodesmium, and has >99% nucleotide sequence similarity to environmental sequences from the tropical Atlantic (AY896353; Langlois et al., 2005) and the South China Sea (EU052348; Moisander et al., 2008). This phylotype was amplified from all stations, except offshore Station D. CV4 (7%) clustered with UCYN-A, which has been previously reported in this region of the ocean (Langlois et al., 2005, 2008; Goebel et al., 2010). CV4 was amplified from offshore and oligotrophic stations A, D, E and F and has 99.7% nucleotide sequence similarity to sequences reported in the North Pacific (e.g., EU159536; Fong et al., 2008) and Gulf of Aqaba (DQ825729; Foster et al., 2009a).

CV5 (5.1%) is most closely related (90% nucleotide similarity) to a nifH sequence from an uncultivated α-proteobacteria (AF389713) associated with a marsh cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora (Lovell et al., 2001). This phylotype is closely related (88% nucleotide similarity) to α-24809A06, which Moisander et al. (2008) used in the design of a qPCR assay, but has too many mismatches in the primer/probe region to be amplified. CV6 (4.8%) is related to a γ-proteobacteria (82% nucleotide sequence similarity) described in DNA-derived nifH clone libraries in an anti-cyclonic eddy near Station ALOHA (Fong et al., 2008).

Transcripts originating from other diazotrophic Cyanobacteria were amplified, but were not among the most highly recovered phlyotypes. One UCYN-B nifH transcript (CV34) was amplified from F25, and three nifH transcripts (CV21) were amplified from D17 and F25 that formed a bootstrap-supported cluster with Richelia sequences (Figure 1). The UCYN-B sequence had no mismatches in the region of the qPCR primers and probe used in this study, and thus represented a phylotype that would be amplified in RT-qPCR assays. However, the Richelia-like sequences had multiple mismatches to the RR and HR qPCR primers and probes, hence are not representative of the phylotypes amplified in the RT-qPCR assays.

Of the remaining 43 OTUs recovered, none account for more than 2% of the total transcripts and it is difficult to assess their relative importance to BNF. Diazotrophs are typically found in low abundance in marine systems, and a nested PCR protocol (>55 amplification cycles) is required to amplify the nifH gene. Clone libraries generated using these amplicons may contain heterotrophic nifH sequences amplified from organisms or nucleic acids present in PCR reagents (Kulakov et al., 2002; Zehr et al., 2003a; Goto et al., 2005; Farnelid et al., 2009), high-purity water systems (Matsuda et al., 1996) or sampling equipment. It is insufficient to run negative controls, as amplification of contaminant nifH is sporadic and difficult to reproduce. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine from nifH sequences alone whether a heterotrophic sequence came from the environment or contamination, and sometimes the contaminant sequences amplify more efficiently in the presence of target DNA (Zehr et al., 2003b).

A representative subset of sequences identified as contaminants have been included in Figure 1. Although most of these are Cluster I sequences, a Cluster III sequence has been reported (AB198377; Goto et al., 2005). CV9 has 99% nucleotide similarity to a known PCR contaminant, AB198391 (Goto et al., 2005), and is presumed to be a contaminant. Other sequences may be contaminants based on their sequence similarity to known or suspected contaminants, for example, CV37. As definitively identifying contaminants in nifH clone libraries is nearly impossible, this study focuses on highly recovered OTUs and those for which qPCR assays have been designed.

Quantitative nifH gene expression (RT-qPCR)

The nifH expression of five Cyanobacteria, Trichodesmium, UCYN-A and UCYN-B, two symbiotic strains of Richelia intracellularis (referred to as RR and HR when associated with diatom Rhizosolenia and Hemiaulus hauckii, respectively), as well as two proteobacteria, γ-24774A11 and α-24809A06, was quantified for each sample (Table 1, Figure 2). UCYN-A was responsible for the highest nifH expression measured, 1.3 × 105 nifH transcripts per l, in the offshore waters at Station A (Table 1). UCYN-A nifH expression also dominated the quantified nifH transcripts at Stations B, D and E (Figure 2). UCYN-A nifH transcripts were not detected at Station C, in which the lowest salinities were measured (near-shore coastal), and were low in abundance at Station F (open ocean oligotrophic) (Table 1). This high UCYN-A nifH expression contrasts with nifH expression dominated by Trichodesmium in the eastern equatorial Atlantic (approximately 3000 km southeast), despite the presence of UCYN-A (Foster et al., 2009b). However, Goebel et al. (2010) reported high abundances of UCYN-A near the Cape Verde Islands, and based on modelled BNF rates, concluded UCYN-A may be responsible for a majority of the BNF in this region. Although no overall correlation was supported between UCYN-A nifH expression and BNF rates (r2=0.12, P=0.09, n=25) across these six stations (Supplementary Table 1), these findings suggest that UCYN-A may contribute to the high BNF rate measured at Station A. As indicated by the linear regression results, however, high UCYN-A nifH transcript abundance does not always correlate to high BNF, exemplified by Station E (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Relative contribution of individual diazotrophs to overall nifH transcript pools quantified in surface waters at each station as determined by RT-qPCR. Results from sample B4 were not included, as it was taken below the mix layer. The α-24809A06 phylotype was not detected in any sample. Map produced using http://www.aquarius.geomar.de/omc/make_map.html.

Trichodesmium was the dominant nifH-expressing phylotype at only one station, the near-shore coastal Station C. Trichodesmium nifH transcripts also accounted for ∼25% of the quantified nifH transcripts at the other near-shore coastal site, Station B. These were the only two stations where NO3−+NO2− was detected. Trichodesmium nifH expression did not have any significant correlations to BNF rates or other environmental parameters measured (Supplementary Table 1).

RR and HR had the highest nifH expression at Stations F and C, respectively (Table 1, Figure 2). Station F constitutes an open ocean, oligotrophic environment where sea surface temperatures ranged between 22.6 °C and 23.3 °C, while station C is coastal, relatively nutrient replete and slightly warmer (24.6–24.9 °C) (Table 1). RR nifH copies per l were found to be inversely correlated with temperature (r2=0.18, P=0.03, n=27), which is consistent with observations in the eastern equatorial Atlantic by Foster et al. (2009b), in which highest RR nifH transcription was detected at stations with lower sea surface temperatures.

Although there were no nifH transcripts detected in any sample for α-24809A06, γ-24774A11 was detected at four stations and quantified at Stations E and F (Table 1), and found to be positively correlated to salinity (r2=0.18, P=0.03, n=27) and RR nifH copies per l (r2=0.62, P=0.04, n=7) and negatively correlated to temperature (r2=0.23, P=0.01, n=27). At Station F, the northernmost station with the lowest temperature and the highest salinity, γ-24774A11 nifH transcripts accounted for 40% of the quantified transcripts (Figure 2). This was the only station where a proteobacteria dominated nifH expression, which is surprising considering that all of the cyanobacterial phylotypes were also detected. Although BNF rates were low at this station, these findings indicate that γ-24774A11 may contribute to N2 fixation in oligotrophic waters.

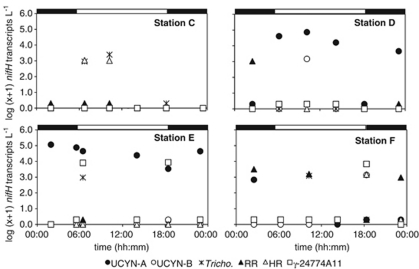

Diel cycling of nifH gene expression (RT-qPCR)

At Stations C–F, samples were taken every 4 h over a 20-h cycle, and can be used to examine diel nifH gene expression patterns of nifH phylotypes. Interpretations of temporal patterns assume that consistent populations of diazotrophs were sampled, but it must also be considered that patterns could be due, in part, to variability in biomass between samples.

UCYN-A exhibited different diel patterns of nifH expression at Stations D and E (Figure 3). At Station D, highest nifH expression was detected during daylight at 1010 hours (7.3 × 104 nifH transcripts per l). In contrast, at Station E, the highest nifH expression (1.2 × 105 nifH transcripts per l) was measured at 0155 hours and was considerably lower during the daytime (Figure 3). It is now known that UCYN-A has a photofermentative metabolism, as sequencing of the complete genome revealed it lacks photosystem II as well as all known carbon fixation pathways (Zehr et al., 2008; Tripp et al., 2010). Therefore, oxidative stress is not a factor directly impacting the temporal patterns of N2 fixation in UCYN-A.

Figure 3.

Diel expression of cyanobacterial and proteobacterial nifH gene expression determined using RT-qPCR at Stations C–F. Sample C5 has been omitted from these plots owing to discrepancies in T/S. Bars at the top of each graph indicate night time (black) and daytime (white). If nifH transcripts per l were measured as DNQs, they were conservatively estimated to be 1 nifH transcript per l.Tricho.—Trichodesmium; RR—Richelia associated with Rhizosolenia; HR—Richelia associated with Hemiaulus.

The other unicellular diazotrophs, UCYN-B and γ-24774A11, had similar diel expression patterns at Station F, in which nifH transcription peaked in early evening at 1820 hours (Figure 3). At Station D, UCYN-B nifH expression peaked during the daytime, which is inconsistent with previous reports of UCYN-B temporally separating N2 fixation from oxygenic photosynthesis to protect nitrogenase from oxidative damage (Bergman et al., 1997). At Station E, nifH expression in γ-24774A11 appeared to have two peaks of similar magnitude in the early morning (0625 hours) and early evening (1825 hours). Consistent with findings from Church et al. (2005b), it appears that nifH expression in γ-24774A11 is not directly impacted by light intensity.

Diel expression of nifH in Trichodesmium was consistent with that observed in culture (Wyman et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1998) and in situ (Church et al., 2005b), with highest nifH transcript copies quantified in the early (Stations E) or mid-morning (Stations C and F). HR and RR showed slightly different diel patterns, with RR showing highest nifH expression at 0230 hours at Stations D and F, and HR in the early to mid-morning at Station C.

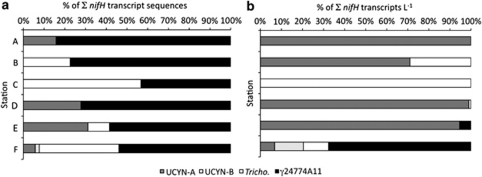

Comparison between nifH expression via RT-PCR and RT-qPCR

Results of RT-qPCR indicate that Cyanobacteria are responsible for the majority of nifH transcription at the time of sampling around the Cape Verde Islands. It must be noted, however, that diazotrophic phylotypes not specifically targeted by these qPCR assays may contribute to the pool of nifH transcripts, and possibly BNF rates. However, the RT-qPCR results contrast with those from RT-PCR clone libraries, which are dominated by non-cyanobacterial sequences.

Out of the seven phylotypes targeted by RT-qPCR assays, four were amplified in the RT-PCR libraries and had 0 or very few (<2) mismatches in the regions of the primers and probes. These were UCYN-A (CV4), UCYN-B (CV34), Trichodesmium (CV3) and γ-24774A11 (CV1). Three of these phylotypes are among those most highly amplified in the clone libraries.

To compare the two methods, the number of nifH transcripts amplified via RT-PCR from these four phylotypes were normalized to a subset of the total number of sequences recovered at each station (omitting all phylotypes but CV1, CV3, CV4 and CV34). Likewise, the number of nifH transcripts per l for these four phylotypes from the RT-qPCR study were summed and used to normalize each individual phylotype. A comparison of normalized distributions of these four phylotypes from RT-PCR libraries and RT-qPCR results at each station indicate that γ-24774A11 was preferentially amplified at all stations (Figure 4). This is most clearly shown at Station D, in which no γ-24774A11 nifH transcripts were quantified via RT-qPCR, but CV1 accounted for 34/54 transcript sequences.

Figure 4.

Comparison of results from RT-PCR and RT-qPCR for UCYN-A, UCYN-B, Trichodesmium and γ-24774A11 at each station. (a) Frequency of each phylotype occurring in the RT-PCR clone libraries normalized to the sum of frequencies for all four phylotypes. (b) Percent contribution of individual phylotypes to the total nifH transcripts per l detected via RT-qPCR at all stations.

There were minor differences in the cDNA generation for the RT-PCR and RT-qPCR portions of this study (described above). It is unclear as to what effect, if any, this may have on the results. Whether the preferential amplification of γ-24774A11 in the RT-PCR libraries resulted from minor protocol differences, or the nature of PCR amplification, these findings underscore the importance of coupling PCR-based analysis with more quantitative molecular approaches.

Conclusions

This study documented high rates of BNF at several stations, which are comparable with BNF rates reported in the Eastern Mediterranean and oligotrophic Pacific. As in previous studies, the rate of BNF was positively correlated with dissolved Fe concentration, providing evidence for a more substantial link between BNF and Saharan dust deposition.

Although this study draws attention to the limitations of RT-PCR-based studies, two phylotypes for which no qPCR assays exist, CV2 and CV5, were highly amplified and may be ecologically relevant diazotrophs in this region of the ocean.

UCYN-A had the highest nifH expression among the targeted phylotypes and dominated at the station with the highest BNF rate, which indicates they may be important contributors to BNF in this region. The most oligotrophic site had the lowest BNF rate, but was also the only station in which transcripts from all cyanobacterial phylotypes and γ-24774A11 were quantified. Although this study did not reveal a significant correlation between any one diazotroph and measured BNF rates, it is the first study that documents nifH expression in waters near the Cape Verde Islands and makes a significant contribution to understanding diazotrophic community composition in the tropical eastern North Atlantic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gill Malin and the officers and crew of the Royal Research Ship Discovery during Cruise D325. This work was supported by Natural Environment Research Council through the UK SOLAS research programme and contributes to Theme 2 of the Plymouth Marine Laboratory Oceans2025 core programme. Natural Environment Research Council provided additional funding under Grant NE/C507902/1. Molecular work was supported by a Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Marine Investigator Grant.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Bergman B, Gallon JR, Rai AN, Stal LJ. N2 fixation by non-heterocystous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;19:139–185. [Google Scholar]

- Berman-Frank I, Quigg A, Finkel ZV, Irwin AJ, Haramaty L. Nitrogen-fixation strategies and Fe requirements in cyanobacteria. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007;52:2260–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Bird C, Martinez Martinez J, O'Donnell AG, Wyman M. Spatial distribution and transcriptional activity of an uncultured clade of planktonic diazotrophic γ-proteobacteria in the Arabian Sea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2079–2085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.2079-2085.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer PG, Riley JP. The automatic determination of nitrate in sea water. Deep-Sea Res. 1965;12:765–772. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-B, Dominic B, Mellon MT, Zehr JP. Circadian rhythm of nitrogenase gene expression in the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. strain IMS 101. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3598–3605. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3598-3605.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapello I, Bergametti G, Gomes L, Chatenet B, Dulac F, Pimenta J, et al. An additional low layer transport of Sahelian and Saharan dust over the North-Eastern Tropical Atlantic. Geophys Res Lett. 1995;22:3191–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Church MJ, Bjorkman KM, Karl DM, Saito MA, Zehr JP. Regional distributions of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the Pacific Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Church MJ, Jenkins BD, Karl DM, Zehr JP. Vertical distributions of nitrogen-fixing phylotypes at Stn ALOHA in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2005a;38:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Church MJ, Short CM, Jenkins BD, Karl DM, Zehr JP. Temporal patterns of nitrogenase gene (nifH) expression in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005b;71:5362–5370. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5362-5370.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Baar HJW, Timmermans KR, Laan P, de PortoHH, Ober S, Blom JJ, et al. Titan: A new facility for ultraclean sampling of trace elements and isotopes in the deep oceans in the international Geotraces program. Mar Chem. 2008;111:4–21. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JTM, den Das J, Bathmann U, Stoll MHC, Kattner G, Nolting RF, et al. Dissolved iron at subnanomolar levels in the Southern Ocean as determined by ship-board analysis. Anal Chim Acta. 1998;377:113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Falcón LI, Cipriano F, Chistoserdov AY, Carpenter EJ. Diversity of diazotrophic unicellular cyanobacteria in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5760–5764. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5760-5764.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnelid H, Oberg T, Riemann L. Identity and dynamics of putative N-2-fixing picoplankton in the Baltic Sea proper suggest complex patterns of regulation. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2009;1:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong AA, Karl D, Lukas R, Letelier RM, Zehr JP, Church MJ. Nitrogen fixation in an anticyclonic eddy in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. ISME J. 2008;2:663–676. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RA, Paytan A, Zehr JP. Seasonality of N2 fixation and nifH diversity in the Gulf of Aqaba (Red Sea) Limnol Oceanogr. 2009a;54:219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Foster RA, Subramaniam A, Mahaffey C, Carpenter EJ, Capone DG, Zehr JP. Influence of the Amazon River plume on distributions of free-living and symbiotic cyanobacteria in the western tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007;52:517–532. [Google Scholar]

- Foster RA, Subramaniam A, Zehr JP. Distribution and activity of diazotrophs in the Eastern Equatorial Atlantic. Environ Microbiol. 2009b;11:741–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel NL, Turk KA, Achilles KM, Paerl RW, Hewson I, Morrison AE, et al. Abundance and distribution of major groups of diazotrophic cyanobacteria and their potential contribution to N2 fixation in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:3272–3289. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M, Ando S, Hachisuka Y, Yoneyama T. Contamination of diverse nifH and nifH-like DNA into commercial PCR primers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;246:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski MNW, Church MJ, Karl DM. Nitrogen fixation rates and controls at Stn ALOHA. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2008;52:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Grasshoff K, Kremling K, Ehrhardt M.(eds) (1999Methods of Seawater Analysis Wiley-VCH: Weinheim; 600 [Google Scholar]

- Gruber N, Sarmiento JL. Global patterns of marine nitrogen fixation and denitrification. Global Biogeochem Cy. 1997;11:235–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hewson I, Moisander PH, Morrison AE, Zehr JP. Diazotrophic bacterioplankton in a coral reef lagoon: phylogeny, diel nitrogenase expression and response to phosphate enrichment. ISME J. 2007;1:78–91. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl D, Letelier R, Tupas L, Dore J, Christian J, Hebel D. The role of nitrogen fixation in biogeochemical cycling in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature. 1997;388:533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Karl D, Michaels A, Bergman B, Capone D, Carpenter E, Letelier R, et al. Dinitrogen fixation in the world's oceans. Biogeochem. 2002;57/58:47–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood DS. Simultaneous determination of selected nutrients in sea water. ICES CM. 1989;1989/C:29. [Google Scholar]

- Kulakov LA, McAlister MB, Ogden KL, Larkin MJ, O'Hanlon JF. Analysis of bacteria contaminating ultrapure water in industrial systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1548–1555. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1548-1555.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustka A, Carpenter EJ, Sanudo-Wilhelmy SA. Iron and marine nitrogen fixation: progress and future directions. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois RJ, Hummer D, LaRoche J. Abundances and distributions of the dominant nifH phylotypes in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:1922–1931. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01720-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois RJ, LaRoche J, Raab PA. Diazotrophic diversity and distribution in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7910–7919. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7910-7919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRoche J, Breitbarth E. Importance of the diazotrophs as a source of new nitrogen in the ocean. J Sea Res. 2005;53:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell CR, Friez MJ, Longshore JW, Bagwell CE. Recovery and phylogenetic analysis of nifH sequences from diazotrophic bacteria associated with dead aboveground biomass of Spartina alterniflora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5308–5314. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5308-5314.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, Yadhukumar, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1363–1371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey C, Michaels AF, Capone DG. The conundrum of marine N2 fixation. Am J Sci. 2005;305:546–595. [Google Scholar]

- Man-Aharonovich D, Kress N, Bar Zeev E, Berman-Frank I, Beja O. Molecular ecology of nifH genes and transcripts in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2354–2363. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N, Agui W, Tougou T, Sakai H, Ogino K, Abe M. Gram-negative bacteria viable in ultrapure water: identification of bacteria isolated from ultrapure water and effect of temperature on their behavior. Colloids Surfaces B. 1996;5:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mills MM, Ridame C, Davey M, La Roche J, Geider RJ. Iron and phosphorus co-limit nitrogen fixation in the eastern tropical North Atlantic. Nature. 2004;429:292–294. doi: 10.1038/nature02550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr W, Grosskopf T, Wallace DW, LaRoche J. Methodological underestimation of oceanic nitrogen fixation rates. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisander PH, Beinart RA, Hewson I, White AE, Johnson KS, Carlson CA, et al. Unicellular cyanobacterial distributions broaden the oceanic N2 fixation domain. Science. 2010;327:1512–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1185468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisander PH, Beinart RA, Voss M, Zehr JP. Diversity and abundance of diazotrophic microorganisms in the South China Sea during intermonsoon. ISME J. 2008;2:954–967. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisander PH, Morrison AE, Ward BB, Jenkins BD, Zehr JP. Spatial–temporal variability in diazotroph assemblages in Chesapeake Bay using an oligonucleotide nifH microarray. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:1823–1835. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JP, Holl CM, Zehr JP, Hansen A, Villareal TA, Capone DG. High rates of N2 fixation by unicellular diazotrophs in the oligotrophic Pacific Ocean. Nature. 2004;430:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature02824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JP, Voss M, Kahler P, Capone DG. A simple, high-precision, high-sensitivity tracer assay for N2 fixation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:986–993. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.986-993.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld JD, Schafer H, Cox MJ, Boden R, McDonald IR, Murrell JC. Stable-isotope probing implicates Methylophaga spp and novel gammaproteobacteria in marine methanol and methylamine metabolism. ISME J. 2007;1:480–491. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens NJP, Rees AP. Determination of nitrogen-15 at sub-microgram levels of nitrogen using automated continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Analyst. 1989;114:1655–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Rees AP, Gilbert JA, Kelly-Gerreyn BA. Nitrogen fixation in the western English Channel (NE Atlantic Ocean) Mar Ecol-Prog Ser. 2009;374:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rees AP, Law CS, Woodward EMS. High rates of nitrogen fixation during an in-situ phosphate release experiment in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Geophys Res Lett. 2006;33:L10607. [Google Scholar]

- Rijkenberg MJA, Powell CF, Dall'Osto M, Nielsdottir MC, Patey MD, Hill PG, et al. Changes in iron speciation following a Saharan dust event in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Mar Chem. 2008;110:56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo-Wilhelmy SA, Kustka AB, Gobler CJ, Hutchins DA, Yang M, Lwiza K, et al. Phosphorus limitation of nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium in the central Atlantic Ocean. Nature. 2001;411:66–69. doi: 10.1038/35075041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthou G, Bakerb AR, Blain S, Achterberg EP, Boye M, Bowie AR, et al. Atmospheric iron deposition and sea-surface dissolved iron concentrations in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Res I. 2003;50:1339–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1501–1506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1501-1506.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp HJ, Bench SR, Turk KA, Foster RA, Desany BA, Niazi F, et al. Metabolic streamlining in an open ocean nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Nature. 2010;464:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature08786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek PM, Howarth RW. Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea: How can it occur. Biogeochem. 1991;13:87–115. [Google Scholar]

- Welschmeyer NA. Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll a in the presence of chlorophyll b and phaeopigments. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:1985–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman M, Zehr JP, Capone DG. Temporal variability in nitrogenase gene expression in natural population of the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium thiebautii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1073–1075. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1073-1075.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zani S, Mellon MT, Collier JL, Zehr JP. Expression of nifH genes in natural microbial assemblages in Lake George, NY detected with RT-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3119–3124. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.3119-3124.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Bench SR, Carter BJ, Hewson I, Niazi F, Shi T, et al. Globally distributed uncultivated oceanic N2-fixing cyanobacteria lack oxygenic Photosystem II. Science. 2008;322:1110–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1165340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Crumbliss LL, Church MJ, Omoregie EO, Jenkins BD. Nitrogenase genes in PCR and RT-PCR reagents: implications for studies of diversity of functional genes. Biotechniques. 2003a;35:996–1005. doi: 10.2144/03355st08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Jenkins BD, Short SM, Steward GF. Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure: a cross-system comparison. Environ Microbiol. 2003b;5:539–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, McReynolds LA. Use of degenerate oligonucleotides for amplification of the nifH gene from the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium thiebautii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2522–2526. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2522-2526.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Montoya JP, Jenkins BD, Hewson I, Mondragon E, Short CM, et al. Experiments linking nitrogenase gene expression to nitrogen fixation in the North Pacific subtropical gyre. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007;52:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Paerl HW.2008Molecular ecological aspects of nitrogen fixation in the marine environmentIn: Kirchman DL (ed).Microbial Ecology of the Oceans2nd edn.Wiley-Liss Inc.: Durham, NC; 481–525. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JP, Waterbury JB, Turner PJ, Montoya JP, Omoregie E, Steward GF, et al. Unicellular cyanobacteria fix N2 in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature. 2001;412:635–638. doi: 10.1038/35088063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.