Abstract

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) is a modular enzyme which catalyzes condensation of serine with homocysteine. Cross-talk between the catalytic core and the C-terminal regulatory domain modulates the enzyme activity. The regulatory domain imposes an autoinhibition action that is alleviated by S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) binding, by deletion of the C-terminal regulatory module, or by thermal activation. The atomic mechanisms of the CBS allostery have not yet been sufficiently explained. Using pulse proteolysis in urea gradient and proteolytic kinetics with thermolysin under native conditions, we demonstrated that autoinhibition is associated with changes in conformational stability and with sterical hindrance of the catalytic core. To determine the contact area between the catalytic core and the autoinhibitory module of the CBS protein, we compared side-chain reactivity of the truncated CBS lacking the regulatory domain (45CBS) and of the full-length enzyme (wtCBS) using covalent labeling by six different modification agents and subsequent mass spectrometry. Fifty modification sites were identified in 45CBS, and four of them were not labeled in wtCBS. One differentially reactive site (cluster W408/W409/W410) is a part of the linker between the domains. The other three residues (K172 and/or K177, R336, and K384) are located in the same region of the 45CBS crystal structure; computational modeling showed that these amino acid side chains potentially form a regulatory interface in CBS protein. Subtle differences at CBS surface indicate that enzyme activity is not regulated by conformational conversions but more likely by different allosteric mechanisms.

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS,1 EC 4.2.1.22) is a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) dependent enzyme which catalyzes the first step of the transsulfuration pathway, namely, the condensation of serine with homocysteine to cystathionine (1). Its deficiency due to missense mutations in the CBS gene is the most common cause of inherited homocystinuria, a treatable multisystemic disease affecting to various extent vasculature, connective tissues, and central nervous system (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/236200). More than 100 different pathogenic amino acid substitutions in the CBS protein were described, and the missense mutations represent 86% of all analyzed patient alleles (http://www.uchs.edu/cbs/cbsdata/cbsmain.htm).

Human CBS is a homotetrameric protein, and each subunit (61 kDa) consists of 551 amino acids. The protein sequence comprises three regions: the N-terminal heme-binding domain (1−69), a highly conserved catalytic core (70−413), and the C-terminal regulatory domain (414−551) (2), an autoinhibitory module with binding site for the allosteric activator, AdoMet (3).

CBS activity can be stimulated in vitro by several processes: by allosteric binding of S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) (3), by proteolytic cleavage yielding the C-terminally truncated dimer containing identical subunits with molecular mass of 45 kDa (4), or by heat activation (3,5). Proteolytic activation of CBS was observed also in vivo in rat liver extract (6) and in HepG cell lines (7).

The spatial arrangement of CBS molecule was solved by X-ray crystalography for the truncated 45 kDa enzyme lacking the C-terminal regulatory domain (amino acids 1−413, 45CBS) only (8,9); the 3-D structure belongs to the β-family of PLP enzymes such as O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase or tryptophan synthase. However, the 3-D structure of the full-length CBS (wtCBS) has not yet been determined, and therefore the atomic basis of the enzyme regulation is still unclear. While hydrophobicity of the C-terminal module and putative interdomain motions prevented successful crystallization of wtCBS, alternative techniques can yield at least partial information about the allosteric communication in the wtCBS protein. Using H/D exchange, Sen et al. showed that the region 356−385 exhibited significantly slower rate of deuterium incorporation for wtCBS compared to 45CBS (10). The data were used for evaluation of a protein−protein docking exercise, and a structural model of the full-length CBS was proposed. However, this model has not yet been supported and/or refined by other structural techniques.

In this study, we developed a procedure for covalent labeling of solvent-accessible amino acid residues (11) in purified CBS. Using this technique, we compared reactivity of the side chains in 45CBS and wtCBS with six modifiers. These commonly used compounds specifically react with histidines (diethyl pyrocarbonate; DEP), tyrosines (N-acetylimidazole; NAI), cysteines (N-ethylmaleimide; NEM), lysines (sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimido acetate; NHS), tryptophans (N-bromosuccinimide; NBS), and arginines (4-hydroxyphenylglyoxal; HPG) (12). Surface mapping provided data which faciliated development of the refined model for wtCBS spatial arrangement and enabled insight into the structural basis of the enzyme allosteric regulation.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

If not specified otherwise, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Preparation of 45CBS and wtCBS

The 45CBS and the wtCBS were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogenity as previously described (13,14).

Pulse Proteolysis

Pulse proteolysis was performed as described previously (15,16) with some modifications. Purified 45CBS or wtCBS (0.5 mg/mL) was equilibrated overnight at 4 °C in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM CaCl2 and urea (0−7 M) and then digested by thermolysin from Bacillus thermoproteolyticus (0.1 mg/mL). To carry out pulse proteolysis of wtCBS in the presence of AdoMet, wtCBS was incubated with 300 μM AdoMet at room temperature for 10 min prior to equilibration in urea. The proteolytic pulse (1 min) was quenched in 20 mM EDTA. Protein samples (7.5 μg) were analyzed by SDS−PAGE using Tris−acetate SDS running buffer with 3−8% gradient Tris−acetate precast gels (Invitrogen) and visualized by Coomassie blue solution. Experiments were repeated three times. Band intensities were quantified using GeneTools software (Syngene) and were fitted into the sigmoidal equation:

using Origin 8.0 (Originlab); ffold represents a fraction of folded proteins remaining intact after proteolytic pulse, cm urea concentration at which ffold is 0.5, and c urea concentration. Value of p is a slope of curve at cm, and it reflects unfolding cooperativity.

Proteolytic Kinetics under Native Conditions

Purified proteins (0.5 mg/mL) were diluted in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM CaCl2 and digested by thermolysin (0.1 mg/mL). At the chosen time point, proteolysis was quenched in 20 mM EDTA. SDS−PAGE and band quantification were performed as described for pulse proteolysis. First-order kinetic constant of proteolysis (kp) for each protein was determined by nonliner curve fitting (17).

Preparation of Modified Protein Samples

CBS proteins (1 mg/mL) were diluted in modification buffer and covalently labeled. Each labeling procedure (18−23) (Table S1 in the Supporting Information) was repeated three times. Reaction was quenched by buffer exchange using Zeba Desalt spin columns (ThermoFischer Scientific) with elution by 50 mM NH4HCO3.

Analysis of Modified Proteins

(i) Native Electrophoresis

Labeled proteins (3 μg) were separated using Laemmli buffer system without sodium dodecyl sulfate and with 3−8% gradient Tris−acetate precast gel at 4 °C and visualized by silver staining kit (Promega) according to manufacturer’s manual.

(ii) CBS Activity Assay

Enzyme activity of the proteins was determined in the absence or presence of 1 mM AdoMet by radiometric assay using [14C]-l-serine (Moravek Biochemicals); the previously described method (24) was slightly modified. The reactants and products were separated by thin-layer chromatography using cellulose−HPTLC sheets (Merck) and subsequently visualized using PhosphorImager system (Molecular Dynamics); amount of radioactive cystathionine as the reaction product was determined by ImageQuant 5.0 software (Molecular Dynamics).

(iii) In-Solution Proteins Digestion and Mass Spectrometric Analysis

Labeled proteins were reduced in 5 mM dithiothreitol at 50 °C for 30 min; reduced cysteines were acetamidated in 25 mM iodoacetamide in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, they were digested by trypsin (Promega), chymotrypsin, endoprotease Glu-C, and protease double combinations (25) at 37 °C for 1 h. The CBS:protease ratio (w/w) was 20:1. The protein digest was fractionated by ZipTip (Millipore), and each fraction was mixed with the matrix solution (saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid supplied by Bruker Daltonics, sample:matrix ratio of 1:1 v/v) and measured using Autoflex II (Bruker Daltonics) mass spectrometer equipped with a nitrogen laser (337 nm) in reflector positive mode (m/z range from 500 to 4500). The mass spectrometer was externally calibrated by peptide calibration standard II (Bruker Daltonics). All spectra were processed by Flex Analysis, Biotools 3.0 and mMass 3.0 (26); mass accuracy tolerance was set at 50 ppm for MS and ±0.5 Da for MS/MS analyses (22).

With the exception of labeling with NBS, all other modification sites were identified by detection of labeled peptides that were not detected in unmodified controls (27); expected mass shifts for each reaction are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. The labeling with NBS induces tryptophan oxidation (19) which is also considered to be a common artifact of sample handling (28). Since we observed tryptophan oxidation even in the unmodified controls, the residues labeled with NBS were determined by comparing peak intensities of the modified and the unmodified peptides (29). Tryptophan residues were classified as labeled if the relative intensity of modified peptide increased at least 1.5-fold compared to the unmodified control. Identity of the modified peptides generated from all labeling experiments was confirmed by MS/MS measurements (method LIFT).

In general, mass spectrometric measurements were satisfactorily reproducible; i.e., modification sites were determined identically in the repeated experiments.

Thermal Activation of wtCBS

The wtCBS diluted in the reaction buffer was incubated at 55 °C for 10 min and then chilled on ice (3,5). Thermally activated proteins were labeled and analyzed by native electrophoresis, activity assay, and mass spectrometry as described above.

Protein Structure Modeling

Model of the C-terminal regulatory module was built by homology modeling package Modeller 9v3 (30) using the structure of CBS-domain containing protein MJ0100 from Methanocladococcus jannaschii (PDB ID 3KPB) (31) as a template. The initial sequence−sequence alignment was processed by the web services of PHYRE (32) and PSI-BLAST (33) and further modified manually. The resulting model was evaluated using Prosa web service (34) and statistical coupling/protein sector analysis (35). For this purpose, 6983 protein sequences from CBS subfamily were taken from the Pfam database (36) and analyzed using a Python script based on the procedure introduced by Halabi and co-workers (35).

Model of wtCBS dimer was obtained by docking of a single C-terminal regulatory domain to 45CBS dimer (PDB ID 1JBQ, with missing loops reconstructed by Modeller package) using the program ZDOCK (37). This was followed by addition of the C-terminal domain to the second subunit that was driven by symmetry. Differentially modified residues from the experimental results were forced to be involved in an interdomain interaction during the docking process.

Structural models generated by this approach were visually inspected on the basis of several criteria, namely, involvement of differentially modified resides in the interaction, dimer symmetry, and protein stereochemistry. The full-length dimer was built by Modeller using the best-suited structure from docking procedures.

Results

Pulse Proteolysis and Proteolytic Kinetics under Native Conditions

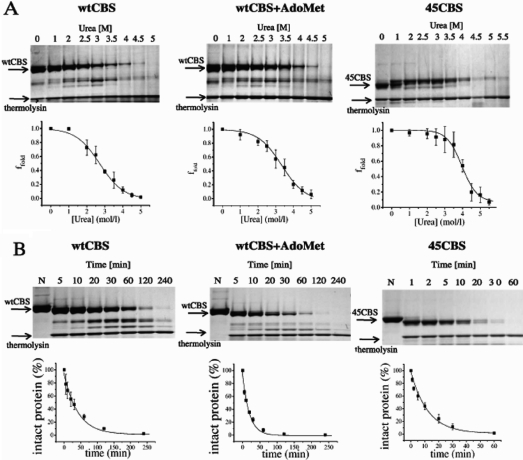

Using pulse proteolysis we determined the global conformational stability and unfolding cooperativity of CBS proteins (Figure 1 and Table 1). The wtCBS exhibited lower resistance to urea-induced denaturation and lower degree of unfolding cooperativity compared to 45CBS. Binding of AdoMet to wtCBS moderately increased the protein stability toward urea, although it remained lower than the 45CBS resistance. On the other hand, unfolding cooperativity of wtCBS did not differ from wtCBS in the presence of AdoMet. These data show that CBS proteins adopt variant conformational states characterized by different degree of the stability.

Figure 1.

Pulse proteolysis in urea gradient (A) and proteolytic kinetics by thermolysin under native conditions (B) of CBS proteins. Below the representative SDS−PAGE gels, the corresponding plots are shown. Points are depicted as a mean with standard deviations; curves were fitted by nonlinear regression. (A) Molar concentration of urea for proteolytic pulse is indicated at the top of each line at the gels. Ffold values which represent fraction of remaining intact protein after the proteolytic pulse are plotted against urea concentration. (B) Portion of remaining protein is plotted against the incubation time. Each line of the gels is marked by designed time point of proteolysis in minutes; “N” refers to uncleaved control.

Table 1. Results from Pulse Proteolysis in Urea Gradient and Proteolytic Kinetics under Native Conditionsa.

| pulse proteolysis |

proteolytic kinetics under native conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| protein | cm (mol/L) | p | kp (min−1) |

| wtCBS | 2.70 ± 0.08 | 1.51 ± 0.15 | 0.026 ± 0.005 |

| wtCBS + AdoMet | 3.26 ± 0.08 | 1.48 ± 0.13 | 0.056 ± 0.005 |

| 45CBS | 4.08 ± 0.07 | 2.20 ± 0.28 | 0.075 ± 0.008 |

The CBS proteins (0.5 mg/mL) were digested with thermolysin (0.1 mg/mL). Data were evaluated by nonlinear curve fitting. Value of cm reflects conformational stability, and value of p is informative about unfolding cooperativity; the constant kp was acquired from the equation of first-rate kinetics.

Proteolytic kinetics by thermolysin under native conditions (Figure 1B) revealed slower cleavage of wtCBS compared to the 45CBS. AdoMet binding to wtCBS accelerated proteolysis; however, it was still slower than cleavage of 45CBS.

These results are concordant with previously proposed regulation mechanisms; i.e., catalytic core is sterically hindered in the full-length protein by the C-terminal regulatory domain, and the hindrance is partially cleared off upon AdoMet binding (3,38). To verify this hypothesis at the atomic level, we compared three-dimensional structures of 45CBS and wtCBS using protein surface mapping.

Surface Mapping of CBS

(i) Sequence Coverage

To reach high degree of protein sequence coverage, 45CBS and wtCBS were digested by three proteolytic enzymes, namely, chymotrypsin, endoprotease Glu-C, and trypsin and by their double combinations; we obtained the sequence coverage of unmodified proteins 89% and 94% for 45CBS and wtCBS, respectively. For each labeling experiment, we selected the digests that yielded the highest amount of reliably identified modified amino acid residues (mass spectrometric data set available in the Supporting Information).

(ii) Modifier Concentrations

In the next step, we optimalized conditions of each labeling reaction as the excess of a modification agent may disrupt the spatial arrangement of a protein (39). Therefore, the lowest concentration of the modifier that enabled efficient mass spectrometric detection of the modified residues was chosen. The integrity of modified proteins was monitored by disruption of their structure manifested by smears and lack of sharp bands on native gels along with complete loss of enzymatic activity. These effects were observed in the case of labeling with tyrosine modifiers tetranitromethane and iodine, and tryptophan modifier 2-hydroxy-5-nitrobenzyl bromide (data not shown). Six other modification agents (Supporting Information Table S1) were feasible for this study since modified CBS proteins migrated as sharp bands on native gels and retained high levels of enzymatic activity (Figure S1 and Table S2 in the Supporting Information). These data showed that most of the modification reactions did not even partially disturb integrity of CBS proteins, with the exception of the 45CBS labeled with NBS. In this case, modification procedure decreased enzyme activity to 43% of the unmodified control. This observation indicated that the labeling reaction may partially affect the catalytic activity. Despite this obstacle, we utilized NBS labeling since it was the only suitable compound for the detecting of solvent-exposed tryptophans. The eventual impact of the modification procedure on the protein integrity should be thus taken into account during structural interpretation.

Modification Sites in CBS

Modification reactions were examined by mass spectrometry, and residues labeled by six different agents were determined. The labeling was monitored qualitatively; i.e., the evaluation was based on the presence/absence of the modified peptides in 45CBS and wtCBS. This approach is commonly known as chemical footprinting (40), a suitable technique for study of protein/protein and protein/DNA interactions (41).

Mass spectrometric analysis revealed 50 and 70 modification sites in 45CBS and wtCBS, respectively (Table 2). Identity of the modified peptides was verified by MS/MS sequencing. However, several sites could not be confirmed due to insufficient fragmentation of the modified peptides (see Table 2). The majority of the unconfirmed peptides contain a modified arginine residue since their tagging may affect the fragmentation process as previously reported (42). Nevertheless, these peptides were included in the data set, since their observed masses were unambiguously assigned against in silico generated digests.

Table 2. Modification Profile of CBS: List of Modified Amino Acidsa.

| modifier | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEP | NBS | NEM | NAI | NHS | HPG |

| G1 | W43 | C15 | G1 | G1 | R18 |

| C15 | W54 | C52 | K25 | K25 | R45 |

| H17 | W208 | C272 | K39 | K39 | R182/R190/R196b |

| H22 | W408/W409/W410 | C370 | K72 | K72 | R209 |

| H65/H66/H67 | M505b | C431 | K137 | K137 | R336b |

| H203 | M529b | K172/K177c | K172/K177 | R369b | |

| K211 | K211 | K211 | R389 | ||

| K406 | K271 | K271 | R413 | ||

| H411 | Y308 | K322 | R439 | ||

| H433 | K322 | K405 | R491b | ||

| H501 | K359 | K406 | R498 | ||

| H507 | K384 | K441 | R527 | ||

| K398/K405b | K472 | R548 | |||

| K406 | K481 | ||||

| K441 | K485 | ||||

| K472 | K488 | ||||

| Y484/K485 | K523 | ||||

| K488 | K551 | ||||

| K523 | |||||

| K551 | |||||

Differentially reactive residues (modified in 45CBS but not in wtCBS) are underlined.

Identity of modified peptide could not have been confirmed by MS/MS due to insufficient fragmentation.

Reactivity of these residues could have been confirmed by MS/MS only in the case of 45CBS.

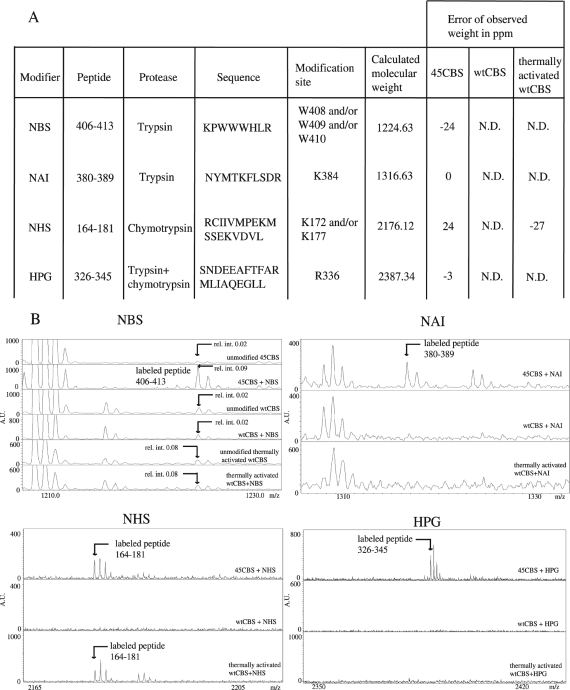

In wtCBS, 46 labeled residues were identified in the active core (region 1−413), and 24 sites were located in the regulatory domain (414−551). Comparing the side-chain reactivity of 45CBS and wtCBS in the region 1−413, we found four sites that were differentially labeled, i.e., modified in 45CBS and not wtCBS (Figure 2; MS/MS spectra are shown in Figures S2−S4 in the Supporting Information). Differentially modified amino acid side chains were found in the peptide 164−181 (residue K172 and/or K177 modified by NHS), in the peptide 326−345 (residue R336 modified by HPG), in the peptide 380−389 (residue K384 modified by NAI), and in the peptide 406−413 (residue W408 and/or W409 and/or W410 modified by NBS).

Figure 2.

Differentially reactive peptides and their modification sites (A) together with corresponding representative spectra (B). Reactivity of the peptides is shown in 45CBS, wtCBS, and thermally activated wtCBS.

Differentially Reactive Peptides in Thermally Activated CBS

Lack of reactivity of the above four peptides in wtCBS could be explained by interdomain sterical hindrance that is independent of the regulatory motions or by conformational changes which modulate the enzymatic activity. Thus, we tested whether the reactivity of the residues can be restored by stimulating activity of wtCBS. If so, such a result would suggest that the residues are involved in conformational motions; on the other hand, persistent unreactivity of these side chains would indicate their location at the fixed interdomain interface. Since the surface mapping in the presence of AdoMet could not be performed due to this ligand’s reactivity toward most of the modifiers, thermally activated wtCBS was analyzed as a surrogate. This approach is feasible since allosteric changes due to AdoMet binding and partial heat denaturation share a common mechanism (3).

For covalent labeling of the stimulated wtCBS we applied only the modifiers and the digestions which provided differentially reactive peptides. Structural integrity of thermally activated wtCBS was preserved after the labeling reactions to an extent similar to the nondenatured wtCBS at the same concentration of modifier (enzyme activities are shown in Table S3, Supporting Information). The restoration of the residue reactivity was observed only for peptide 164−181 labeled by NHS, while the other three peptides were not labeled in thermally activated wtCBS (Figure 2). These findings indicate that both sterical hindrance and regulatory motions are responsible for the differential reactivity of the residues.

Structural Prediction Using Computational Modeling

Initially, homology model of the C-terminal regulatory domain was built using archeal CBS domain as a template (31). The amino acid sequence identity was 16% for the template-model pair. Nevertheless, CBS domains form a conserved tertiary structure despite rather low sequence identity of individual proteins (43).

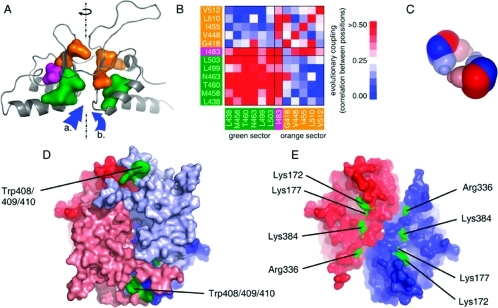

Since this structural module contains many flexible loops, additional restraints were applied; namely, residues 466−472 and 537−549 of the CBS were forced to α-helix formation according to secondary structure prediction, and the distance between Cα atom of L412 and CD2 of L539 was restrained to 4 Å according to structural data of the template.The resulting structure was evaluated by Prosa and yielded a value of −6.38 which is comparable to values usual for experimental structures of the same size and similar to the score for the single subunit of the template (−7.50). Moreover, statistical coupling/protein sector analysis was used for evaluation of the model. Protein sectors are coevolving networks of residues supposed to play a common role (i.e., catalytic, stabilizing etc.) and thus showing a spatial proximity. Two sectors with evolutionary coupled residues were identified in the autoregulatory domain (Figure 3A), showing a strong coevolution within each sector but a loose one between each other (Figure 3B). The residues from the particular sector were found next to each other in the homology model which indicated a high plausibility of the resulting structure. In addition, the residue I483 was located at the sector interface and revealed strong coupling with both sectors (further details on SCA/sectors can be obtained in the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

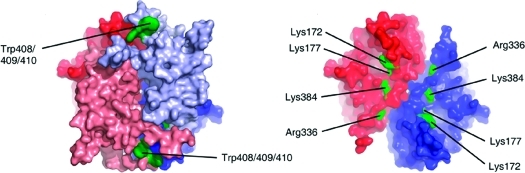

Computational modeling of CBS structure. (A) Model of C-terminal domain generated by homology modeling. Reliability of the built structure was assessed by protein sector analysis. Each sector is depicted by its particular color (green and orange, respectively); residue I483, coupled in both sectors, is indicated in magenta. The dashed line indicates the axis of pseudo-2-fold symmetry of the subunit; arrows show the potential binding sites for AdoMet. (B) Statistical coupling between sector residues. It illustrates that these positions in the structure of the autoregulatory domain are strongly coupled within each sector but loosely coupled between the two sectors. Colors of the sectors are consistent with panel A. (C) Scheme of tetrameric assembly in CBS using available structural data. Dimer−dimer interface is located between the autoinhibitory domains. Dimers of catalytic core are colored in dark color, autoinhibitory modules are depicted in light colors. (D) Structural model of dimeric wtCBS. Position of differentially reactive cluster W408/9/10 is indicated in green. Each subunit is depicted in particular color, red and blue, respectively. Autoinhibitory module is colored in light colors; catalytic core is depicted darkly. (E) Differentially reactive residues located in crystal structure of 45CBS, indicated in green. Each subunit in dimer is colored in blue and red, respective.

In the next step, the modeled C-terminal domain (residues 410−545) was docked onto the available structure of 45CBS. The initial docking was not successful, indicating that certain conformational changes in the catalytic domain may be associated with the binding of the regulatory domain. Therefore, the sterically hindering C-terminal helical region of the catalytic domain (residues 385−397) was deleted, and the truncated structure was used as bait with residues K172, K177, and R336 being forced to interaction. Other differentially reactive residues (K384 and W408/409/410) were not involved in docking as they are located in the linker between the catalytic and autoregulatory domains; their topology was used rather for verification of the resulted models. This modified docking procedure resulted in the generation of 79 structures; model no. 32 was selected by visual inspection on the basis of the location of the differentially modified residues, protein symmetry, and general stereochemistry. Using the result from the docking procedures, the structure of the full-length dimer was built. Plausibility of the structural model is greatly supported by data from surface mapping experiments: differentially reactive residues are located at the regulatory interface while residues modified in 45CBS as well as in wtCBS are still solvent-accessible (see Figure 3D,E; structural model is available in the Supporting Information). However, the resulting model represents a possible structural interpretation of our experimental data and should not be interpreted as an atom-resolved structure due to limitations of homology modeling and protein−protein docking procedures.

Discussion

Regulatory Interface in CBS

A cross-talk between the active core and the regulatory domain in CBS modulates its enzyme activity. The main aim of the study was to compare residue reactivity in 45CBS and wtCBS as the differences may reveal the regulatory network. In 45CBS, we identified 50 labeled residues in total, and we found only 4 modification sites which were not detected in wtCBS (Table 2). Using the thermally activated wtCBS as a surrogate of the AdoMet activated enzyme, we tested whether the abolished side-chain reactivity could be restored by the allosteric stimulation. The only differentially reactive peptide 164−181 was labeled in the thermally activated wtCBS, suggesting that this region (namely, residues K172 and/or K177) increases surface accessibility during enzyme stimulation and that it is involved in regulatory motions of CBS. Three other differentially reactive peptides were not labeled in wtCBS even upon thermal activation. Therefore, these side chains (R336, K384, W408 and/or W409 and/or W410) are probably localized at the fixed domain interface.

Contact Area between the Catalytic Core and the Regulatory Domain

Three differentially modified residues (K172 and/or K177, R336, K384) were located in the same region of the 45CBS crystal structure (see Figure 2E), and docking procedure showed that these residues may form an interface between the catalytic core and the regulatory domain. The region possessing differentially reactive sites was also predicted to form interdomain contact area due to the presence of hydrophobic residues on the surface of the 45CBS crystal structure (44). Several CBS patient-derived mutations, namely, the p.V173M (45), the p.E176K (46), and the p.E302K (47), which are located at this putative interface, exhibited enzyme activity similar to wtCBS and failed to be allostericaly stimulated by AdoMet. These observations indicate that mutations of these residues affect interdomain interactions and the CBS allostery.

Another differentially reactive site, the tryptophan cluster W408/9/10, was not previously assigned by the diffraction analysis of the 45CBS crystal; thus we propose that it forms a flexible region in 45CBS and a loop between the active core and the C-terminal domain which is sterically hindered in the wtCBS. As mentioned in the Results, findings dealing with the residues W408/9/10 should be taken with care as modification of 45CBS with NBS led to apparent decrease in enzymatic activity. On the other hand, the electromigration of modified 45CBS was undistinguishable from the unmodified control, indicating that quaternary structure was preserved after the labeling. We assume that the protein structural integrity was not essentially disrupted and that the enzyme activity was affected due to the local conformational changes. Moreover, conclusions about different microenvironment along the tryptophan cluster are also supported by changes in tryptophan flourescence spectra reported previously (3,4).

However, a previously published study involving H/D exchange (10) revealed the interdomain contact at a different region of the CBS structure. Although the changes in microenvironment of K384 were observed by both the H/D exchange and the covalent labeling in the present study, other differentially solvent-accessible regions were found using just single technique. We observed changes in residues K172/K177, R336, and W408/W409/W410, but they were not reported by Sen et al. On the contrary, H/D exchange study revealed differences in the segment of 359−370, but our covalent labeling experiments did not confirm them; in this region, three modification sites (K359, R369, and C370) were identically observed in the both proteins, 45CBS and wtCBS. Similarly to our study, results from H/D exchange were further supported by properties of certain mutant proteins, namely of double-linked mutant p.P78R/K102N (48). Its amino acid substitutions are located in the proximity of the differentially solvent-accessible region 359−370, and this mutant affects the protein allostery driven by AdoMet binding.

The discrepancies between results of covalent labeling and H/D exchange are unclear. The inconsistency may reflect the methodological limitations of each technique. Our experimental setup was designed for identification of differentially reactive sites rather than for quantification of small changes in extent of modification. Mass spectrometry analyses of the reactions were performed qualitatively (with exception of labeling with NBS; see Experimental Procedures) which enabled determination of totally blocked residues only. On the other hand, we might have lost information about subtle conformational motions that would be revealed by quantitative evaluation. Conformational study using H/D exchange has its own limitations as well. It determines the rate of deuterium incorporation to protein backbone from several seconds to hours, and consequently any differences on a short time scale of the exchange may be missed. Therefore, each of these two approaches might locate only particular changes in the CBS protein. Unfortunately, an attempt to generate a model consistent with both data sets was not successful (data not shown). We can speculate that the discrepancies between these studies might arise from different conditions and procedures during preparation of CBS proteins. Consequently, each study would have analyzed only limited set of all possible states from the conformational ensemble. Nevertheless, the inconsistency needs to be examined by additional structural techniques.

Allostery of CBS Is Not Associated with Extensive Conformational Changes

Covalent labeling as well as H/D exchange showed that autoinhibition of the active core by the regulatory domain is associated with only subtle changes at the protein surface. These observations indicate that the CBS allostery is not necessarily directed by extensive conformational motions, suggesting that other factors may play an important role. Changes in structural flexibility and “population shift” as determinants for protein allostery were proposed in the past decade (49−51); it has been shown that the ligand binding often leads to stabilization and/or rigidification of certain conformations (52). As the enzyme activity of CBS proteins (14) is directly proportional to the conformational stability, as determined by pulse proteolysis (Table 1; 45CBS, wtCBS in the presence of AdoMet, wtCBS in the absence of AdoMet, in descending order), it is tempting to speculate that CBS regulation may be driven by changes in protein dynamics. However, detailed knowledge of this type of CBS allostery is limited since the 3-D structure of the protein has not yet been reliably described in sufficient resolution.

AdoMet Binding Site

Furthermore, the designed model of wtCBS provides information about the structural features of several sites with putative regulatory function. Since the spatial arrangement of archeal CBS-domain pair in complex with AdoMet was solved recently (31) and we used this structure as a template for homology modeling of the C-terminal regulatory domain, the possible AdoMet binding site can be proposed. An interesting feature of the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain is its pseudo-2-fold symmetry (the axis indicated in Figure 3A) which forms the basis for two ligand binding sites in each regulatory subunit (a and b in Figure 3A). The experimental structures of the template−ligand complexes showed that the ligands bind to either one of these sites. Sequence similarity does not provide enough information to precisely identify the AdoMet binding site in CBS. However, AdoMet is likely bound in site b (Figure 3A) including the residue D444 that has been identified to be involved in the autoinhibitory function (38).

CXXC Oxidoreductase Motif

CBS also contains the CXXC oxidoreductase motif which spans residues 272−275. Here we identified the C272 as a solvent-exposed residue both in the 45CBS and in the wtCBS. This observation disagrees with a previous study that used three different cysteine modifying agents and an N-terminal sequencing of carboxymethylated peptides (5). However, our findings are in agreement with the crystal structure of the 45CBS. The solvent accessibility of CXXC motif observed in our study may thus support the notion of its possible role in redox sensing (53), although the biological relevance of this observation remains to be answered.

Residues Responsible for Aggregation and Allostery

Other residues, which play important role in CBS function, were revealed by labeling with NAI; this modification decreased the tendency of wtCBS to form higher order oligomers and increased its catalytic activity (Table S2 and Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Similar effect was also observed after modification by NEM as reported previously (5). Frank et al. explained the stabilizing action of the NEM by covalent blocking of C15, the residue responsible for aggregation of wtCBS.

Interestingly, wtCBS labeled with NAI failed to be fully activated upon AdoMet binding while modification of wtCBS by NHS, which exhibited similar modification pattern as NAI (Table 2), did not cause such effects. These data indicate that certain modified residues are responsible for CBS aggregation and also for allosteric activation, and their function can be repressed by covalent blocking of the reactive groups. Comparing the results from labeling with NAI and NHS, we can point out three candidate residues, namely, Y308, K359, and Y484, that are modified by NAI and not by NHS. However, we could not specify the “aggregation inducing“ and “regulation networking“ side chains in this study.

Quarternary Structure of wtCBS

The relevance of the structural model proposed in this paper is limited as dimeric full-length CBS does not explain the atomic basis of the protein tetramerization. Our results from surface mapping revealed a single contact area between the catalytic core and the C-terminal regulatory domain; this is in agreement with the solved structure of the dimeric protein MJ0100 from M. jannaschii containing CBS pairs binding AdoMet (31) and suggests that the autoinhibitory module contains dimer−dimer interface responsible for the CBS tetramer assembly (scheme in Figure 3C). This proposal is also in agreement with the previously built structural model of wtCBS derived from H/D exchange (54).

In summary, we covalently labeled solvent-exposed side chains in CBS, and we identified the interface between the active core and the regulatory domain. The data were applied for generation of the refined full-length CBS structural model. Our results also indicate that the allostery of CBS is not associated with extensive conformational conversion but rather with changes in protein dynamics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Petr Prikryl, Ph.D., for helpful assistance with the mass spectrometry measurements.

Supporting Information Available

(i) Detailed results from the labeling procedures and from the statistical coupling analysis of the autoinhibitory domain; (ii) an overview of the modified peptides that were identified by mass spectrometry; (iii) the generated structural model for the wtCBS illustrating the experimental data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by the Welcome Trust International Senior Research Fellowship in Biomedical Science in Central Europe (Reg. No. 070255/Z/03/Z) and by grants from Grant Agency of Charles University in Prague (No. 0073/2010 and No. 260501). Institutional support was provided by the Research Projects from Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic (No. MSM0021620806 and No. MSM6046137305). J.P.K. was supported by NIH Grant HL065217, by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 09GRNT2110159, and by a grant from the Jerome Lejeune Foundation.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; PLP, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; AdoMet, S-adenosyl-l-methionine; 45CBS, C-terminally truncated CBS; wtCBS, full-length CBS; DEP, diethyl pyrocarbonate; NAI, N-acetylimidazole; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; NHS, sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimido acetate; NBS, N-bromosuccinimide; HPG, 4-hydroxyphenylglyoxal.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mudd S. H.; Finkelstein J. D.; Irreverre F.; Laster L. (1965) Threonine dehydratase activity in humans lacking cystathionine synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 19, 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveriusova J.; Kery V.; Maclean K. N.; Kraus J. P. (2002) Deletion mutagenesis of human cystathionine beta-synthase. Impact on activity, oligomeric status, and S-adenosylmethionine regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48386–48394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janosik M.; Kery V.; Gaustadnes M.; Maclean K. N.; Kraus J. P. (2001) Regulation of human cystathionine beta-synthase by S-adenosyl-l-methionine: evidence for two catalytically active conformations involving an autoinhibitory domain in the C-terminal region. Biochemistry 40, 10625–10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kery V.; Poneleit L.; Kraus J. P. (1998) Trypsin cleavage of human cystathionine beta-synthase into an evolutionarily conserved active core: structural and functional consequences. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 355, 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank N.; Kery V.; Maclean K. N.; Kraus J. P. (2006) Solvent-accessible cysteines in human cystathionine beta-synthase: crucial role of cysteine 431 in S-adenosyl-l-methionine binding. Biochemistry 45, 11021–11029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovby F.; Kraus J. P.; Rosenberg L. E. (1984) Biosynthesis and proteolytic activation of cystathionine beta-synthase in rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 588–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C. G.; Banerjee R. (2003) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced targeted proteolysis of cystathionine beta-synthase modulates redox homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16802–16808.12615917 [Google Scholar]

- Meier M.; Janosik M.; Kery V.; Kraus J. P.; Burkhard P. (2001) Structure of human cystathionine beta-synthase: a unique pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent heme protein. EMBO J. 20, 3910–3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka S.; Lepore B. W.; Kabil O.; Ojha S.; Ringe D.; Banerjee R. (2002) Human cystathionine beta-synthase is a heme sensor protein. Evidence that the redox sensor is heme and not the vicinal cysteines in the CXXC motif seen in the crystal structure of the truncated enzyme. Biochemistry 41, 10454–10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S.; Yu J.; Yamanishi M.; Schellhorn D.; Banerjee R. (2005) Mapping peptides correlated with transmission of intrasteric inhibition and allosteric activation in human cystathionine beta-synthase. Biochemistry 44, 14210–14216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckau D.; Mak M.; Przybylski M. (1992) Protein surface topology-probing by selective chemical modification and mass spectrometric peptide mapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 5630–5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza V. L.; Vachet R. W. (2009) Probing protein structure by amino acid-specific covalent labeling and mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 28, 785–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janosik M.; Meier M.; Kery V.; Oliveriusova J.; Burkhard P.; Kraus J. P. (2001) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the active core of human recombinant cystathionine beta-synthase: an enzyme involved in vascular disease. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank N.; Kent J. O.; Meier M.; Kraus J. P. (2008) Purification and characterization of the wild type and truncated human cystathionine beta-synthase enzymes expressed in E. coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 470, 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.; Marqusee S. (2005) Pulse proteolysis: a simple method for quantitative determination of protein stability and ligand binding. Nat. Methods 2, 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudova A.; Bauman Z.; Braun A.; Vitvitsky V.; Lu S. C.; Banerjee R. (2006) S-adenosylmethionine stabilizes cystathionine beta-synthase and modulates redox capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6489–6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.; Marqusee S. (2004) Probing the high energy states in proteins by proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 343, 1467–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnizda A.; Santrucek J.; Sanda M.; Strohalm M.; Kodicek M. (2008) Reactivity of histidine and lysine side-chains with diethylpyrocarbonate—a method to identify surface exposed residues in proteins. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 70, 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa M.; Kleis-SanFrancisco S.; Proske P. A.; Knaff D. B. (1995) The effect of N-bromosuccinimide on ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 320, 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubalek F.; Pohl J.; Edmondson D. E. (2003) Structural comparison of human monoamine oxidases A and B: mass spectrometry monitoring of cysteine reactivities. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28612–28618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells I.; Marnett L. J. (1992) Acetylation of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase by N-acetylimidazole: comparison to acetylation by aspirin. Biochemistry 31, 9520–9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabant G.; Augier J.; Armengaud J. (2008) Assessment of solvent residues accessibility using three sulfo-NHS-biotin reagents in parallel: application to footprint changes of a methyltransferase upon binding its substrate. J. Mass Spectrom. 43, 360–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carven G. J.; Stern L. J. (2005) Probing the ligand-induced conformational change in HLA-DR1 by selective chemical modification and mass spectrometric mapping. Biochemistry 44, 13625–13637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich V.; Kraus J. P. (1992) Screening for mutations by expressing patient cDNA segments in E. coli: homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 1, 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringer R. G.; Amato H.; Harrington M. G.; Fonteh A. N.; Riggins J. N.; Huhmer A. F. (2006) Enhanced sequence coverage of proteins in human cerebrospinal fluid using multiple enzymatic digestion and linear ion trap LC-MS/MS. Briefings Funct. Genomics Proteomics 5, 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohalm M.; Hassman M.; Kosata B.; Kodicek M. (2008) mMass data miner: an open source alternative for mass spectrometric data analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22, 905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B. T. Jr.; Sabo T. M.; Wilding D.; Maurer M. C. (2004) Mapping of factor XIII solvent accessibility as a function of activation state using chemical modification methods. Biochemistry 43, 9755–9765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdivara I.; Deterding L. J.; Przybylski M.; Tomer K. B. (2010) Mass spectrometric identification of oxidative modifications of tryptophan residues in proteins: chemical artifact or post-translational modification?. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 1114–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J. S.; Becker J. M.; Hettich R. L. (2004) Analysis of protein solvent accessible surfaces by photochemical oxidation and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 76, 672–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A.; Blundell T. L. (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M.; Encinar J. A.; Arribas E. A.; Oyenarte I.; Garcia I. G.; Kortazar D.; Fernandez J. A.; Mato J. M.; Martinez-Chantar M. L.; Martinez-Cruz L. A. (2010) Binding of S-methyl-5′-thioadenosine and S-adenosyl-l-methionine to protein MJ0100 triggers an open-to-closed conformational change in its CBS motif pair. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 800–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L. A.; Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F.; Madden T. L.; Schaffer A. A.; Zhang J.; Zhang Z.; Miller W.; Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl M. J. (1993) Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins 17, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi N.; Rivoire O.; Leibler S.; Ranganathan R. (2009) Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure. Cell 138, 774–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D.; Mistry J.; Tate J.; Coggill P.; Heger A.; Pollington J. E.; Gavin O. L.; Gunasekaran P.; Ceric G.; Forslund K.; Holm L.; Sonnhammer E. L.; Eddy S. R.; Bateman A. (2010) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D211–D222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.; Li L.; Weng Z. (2003) ZDOCK: an initial-stage protein-docking algorithm. Proteins 52, 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evande R.; Blom H.; Boers G. H.; Banerjee R. (2002) Alleviation of intrasteric inhibition by the pathogenic activation domain mutation, D444N, in human cystathionine beta-synthase. Biochemistry 41, 11832–11837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza V. L.; Vachet R. W. (2008) Protein surface mapping using diethylpyrocarbonate with mass spectrometric detection. Anal. Chem. 80, 2895–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaratskhelia M.; Miller J. T.; Budihas S. R.; Pannell L. K.; Le Grice S. F. (2002) Identification of specific HIV-1 reverse transcriptase contacts to the viral RNA:tRNA complex by mass spectrometry and a primary amine selective reagent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15988–15993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair L. P.; Tackett A. J.; Raney K. D. (2009) Development and evaluation of a structural model for SF1B helicase Dda. Biochemistry 48, 2321–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner A.; Lindner W. (2005) Effect of an arginine-selective tagging procedure on the fragmentation behavior of peptides studied by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). Anal. Chim. Acta 528, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ignoul S.; Eggermont J. (2005) CBS domains: structure, function, and pathology in human proteins. Am. J. Physiol. 289, C1369–C1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M.; Oliveriusova J.; Kraus J. P.; Burkhard P. (2003) Structural insights into mutations of cystathionine beta-synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1647, 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urreizti R.; Asteggiano C.; Cozar M.; Frank N.; Vilaseca M. A.; Grinberg D.; Balcells S. (2006) Functional assays testing pathogenicity of 14 cystathionine-beta synthase mutations. Hum. Mutat. 27, 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majtan T.; Liu L.; Carpenter J. F.; Kraus J. P. (2010) Rescue of cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) mutants with chemical chaperones: purification and characterization of eight CBS mutant enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 21, 15866–15873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich V.; Sokolova J.; Klatovska V.; Krijt J.; Janosik M.; Jelinek K.; Kraus J. P. (2010) Cystathionine beta-synthase mutations: effect of mutation topology on folding and activity. Hum. Mutat. 7, 809–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S.; Banerjee R. (2007) A pathogenic linked mutation in the catalytic core of human cystathionine beta-synthase disrupts allosteric regulation and allows kinetic characterization of a full-length dimer. Biochemistry 46, 4110–4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. J.; del Sol A.; Nussinov R. (2008) Allostery: absence of a change in shape does not imply that allostery is not at play. J. Mol. Biol. 378, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern D.; Zuiderweg E. R. (2003) The role of dynamics in allosteric regulation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; Gerick F.; Thornton J. M. (2009) The structural basis of allosteric regulation in proteins. FEBS Lett. 583, 1692–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodey N. M.; Benkovic S. J. (2008) Allosteric regulation and catalysis emerge via a common route. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Madzelan P.; Banerjee R. (2007) Properties of an unusual heme cofactor in PLP-dependent cystathionine beta-synthase. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi M.; Kabil O.; Sen S.; Banerjee R. (2006) Structural insights into pathogenic mutations in heme-dependent cystathionine-beta-synthase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 100, 1988–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.