Abstract

The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether the range of motion exercise of the temporo-mandibular joint (jaw ROM exercise) with a hot pack and massage of the masseter muscle improve biting disorder in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The subjects were 18 DMD patients (21.3 ± 4.1 years old). The jaw ROM exercise consisted of therapist-assisted training (2 times a week) and self-training (before each meal every day). The therapist-assisted training consisted of the application of a hot pack on the cheek of the masseter muscle region (15 minutes), the massage of the masseter (10 minutes), and jaw ROM exercise (5 minutes). The self-training involved jaw ROM exercise by opening the mouth to the maximum degree, ten times. These trainings continued for six months. Outcomes were evaluated by measuring the greatest occlusal force and the distance at the maximum degree of mouth opening between an incisor of the top and that of the bottom. Six months later, the greatest occlusal force had increased significantly compared with that at the start of jaw ROM exercise (intermediate values: from 73.8N to 97.3N) (p = 0.005) as determined by the Friedman test and Scheffé's nonparametric test. The patients' satisfaction with meals increased. However, the maximum degree of mouth opening did not change after six months of jaw ROM exercise. Jaw ROM exercise in DMD is effective for increasing the greatest occlusal force.

Key words: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, exercise, occlusal force

Introduction

The jaw ROM exercise with a hot pack and massage of masseter were effective for occlusal force increase in DMD. The greatest occlusal force was significantly higher 6 months after the jaw ROM exercise than at the start. Furthermore, the jaw ROM exercise reduced patients' fatigue during a meal and gave patients a feeling of satisfaction. We report the effect of this jaw ROM exercise.

Muscle atrophy in DMD progresses with age, and muscle atrophy is not restored naturally. Also, in the muscle involved in deglutition, muscle atrophy is irreversible without exception.

Deglutition is divided into four phases, the preparation, oral, pharynx, and esophageal phases (1). Food is cut into small pieces in the buccal cavity, and mixed with saliva to form an alimentary bolus in the preparation phase. The formed alimentary bolus is transported to the pharynx in the oral phase. In the pharynx phase, the alimentary bolus progresses from the buccal cavity to the pharynx and transfers to the esophagus. In the esophagus phase, the alimentary bolus is transported to the stomach by peristalsis. Many muscles are involved in these phases.

According to a previous study on dysphagia in DMD, disturbance in the preparation and oral phases (the preparation/ oral phase) is already apparent in patients in their teens (2). As patients reach their 20s, they show disturbance in the pharynx phase (3, 4). In the preparation/ oral phase in DMD, decreased occulusal force, malocclusion, macroglossia, and lingual muscle weakness are observed.

The occlusal force of DMD patients in their teens is markedly lower than that of healthy persons of the same age (5). Biting disorder causes loss of appetite, fatigue during meals, and nutritional deficiencies. Moreover, the pleasure of eating is diminished. Therefore, measures against these problems should be taken when patients are still in their teens. However, no report was available that was related to interventions in biting disorder in DMD.

The main causes of biting disorder in DMD are a decreased occlusal force and malocclusion. For malocclusion, forward incisors and posterior molar apertognathia are generally common (6, 7). The therapy for the malocclusion should be orthodontic or orthogonathic in general. However, such therapies are not necessarily applicable to DMD patients. Therefore, we examined whether jaw ROM exercise is feasible for amelioration of biting disorder of such patients, which could be carried out by the bedside.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether jaw ROM exercise with a hot pack and massage improve biting disorder. This study was designed as an open study of jaw ROM exercise of DMD patients.

Patients and methods

Twenty patients with DMD, 16-29 years old, who were admitted to five hospitals were registered in this study. They were not able to sit up without support, did not receive respiratory care during the daytime, had biting disorder, but they ate per os, and did not undergo tube feeding. Two patients stopped the jaw ROM exercise after 4 months of training, because of cardiac insufficiency. We analyzed the data of 18 patients (21.3 ± 4.1 years old male) excluding data of these two patients.

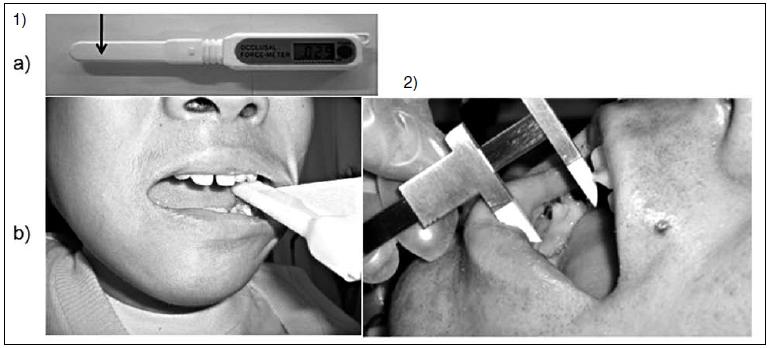

When biting, the jaw joint becomes the fulcrum, and the masseter, temporal muscle, and the medial pterygoid muscle are involved. Among these muscles for biting, the massetter is easy to intervene from the body surface (Fig. 1-a).

Figure 1.

Jaw ROM exercise.

- Anatomy of masseter: The masseter works primarily in mouth closing. In addition, this muscle is easy to intervene from the body surface.

- Hot pack: A therapist warmed the masseter with a hot pack for 15 minutes by supporting the hot pack with his hands so as not to fall.

- Massage: Immediately after the hot pack application, the therapist massaged the masseter with both hands from the top to the bottom to the degree that the patient did not feel pain, 24 times per minute.

- Jaw ROM exercise: Immediately after the masseteric massage, the therapist asked the patient to repeat mouth opening maximally at the patient's own pace for 5 minutes. When the patient opened his mouth, the therapist applied a mild resistance to the chin of the patient using one hand.

The jaw ROM exercise consisted of therapist-assisted training (2 times a week) and self-training (before each meal).

In the therapist-assisted training, the therapist warmed the masseter of the patient with a hot pack and then massaged the masseter to enhance the effect of the jaw ROM exercise. To prepare a hot pack, silica gel was placed in a cloth bag and warmed in hot water of 80°C℃ approximately for 10 min. The warmed bag was covered with a dry towel to protect the skin of the patient from burning, and wrapped in a plastic bag to maintain temperature. The hot pack was placed on the cheek of the masseter muscle region for 15 minutes and supported with the hands so as not to drop (Fig.1-b). Next, immediately after applying a hot pack, the masseter was massaged from the top to the bottom with both hands 24 times per minute to the degree that the patient did not feel pain (Fig.1-c). Immediately after the massage, the therapist asked the patient to perform the jaw ROM exercise repeatedly at his own pace for five minutes. When the patient opened his mouth, the therapist placed a hand under the patient's chin and applied a mild resistance (Fig. 1-d).

In the self-training, the patient performed the jaw ROM exercise in 10 cycles, before each meal three times every day. The therapist-assisted training and self-training were continued for six months.

Outcomes were evaluated by measuring the greatest occlusal force and the distance between an incisor of the top and that of the bottom at the maximum degree of opening the mouth.

In the greatest occlusal force measurement, we used a bite pressure meter (Occlusal Force Meter GM10 (Nagano Keiki)). Each patient was asked to bite the sensor part of the bite pressure meter with the greatest force (Fig. 2-1a). The target tooth for the occlusal force measurement was the first molar. However, when the measurement of the first molar was difficult because of malocclusion, measurement was conducted using another tooth. The measurement was carried out in accordance with the instructions of a dentist, who examined buccal cavity of the patient and observed the occlusion and suggested which tooth is the most suitable if we measure occlusal force. The same examiner measured the same tooth in each evaluation (Fig. 2-1b). Measurement was carried out successively five times.

Figure 2.

Outcome Measurement

-

Measurement of the greatest occlusal force:

- We used a bite pressure meter, Occlusal Force Meter GM10 (Nagano Keiki), for the greatest occlusal force measurement. We asked the patient to bite the sensor part (arrow) of the bite pressure meter with the greatest force.

- The target tooth for the occlusal force measurement was the first molar.

We measured the greatest occlusal force; the same examiner measured each time, using the same tooth. - Measurement of maximum distance between an incisor of the top and that of the bottom at the maximum degree of mouth opening. We measured the maximum degree of mouth opening using a micrometer caliper. We asked the patient to open his mouth to the maximum degree.

We measured the maximum degree of mouth opening using a micrometer caliper (Fig. 2-2). Each patient was instructed to open his mouth to the maximum degree. We measured the degree of mouth opening successively three times. It was determined that this number of measurements did not tire the patients.

Ethical review

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the five participating hospitals (Tokushima National Hospital, Higashisaitama National Hospital, Matsue Medical Center, Hyogochuo National Hospital, Toneyama National Hospital). We explained the details of this study to the patients in a document, and their written informed concent was obtained.

Statistical analysis

The greatest occlusal force and the maximum degree of mouth opening obtained at the start (baseline), 2, 4, and 6 months of jaw ROM exercise were analyzed by the Friedman test (8), respectively. In case that the Friedman test was significant, the nonparametric version of Scheffé test (pairwise comparison) (9) was employed.

Results

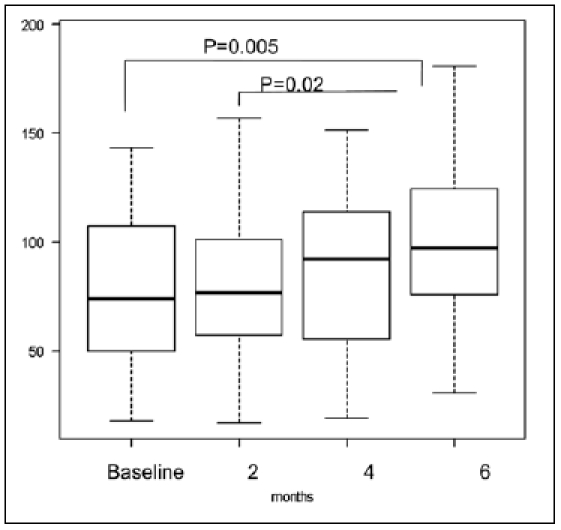

Data of 18 patients were analyzed by the Friedman test and Scheffé test. The greatest occlusal forces (mean ± SD Newton (N)) were 79.0 ± 46.6 N, 80.1 ± 40.4 N, 91.2 ± 40.9 N, and 102.6 ± 37.9 N at the baseline and after two, four, and six months of the jaw ROM exercise. The p value of the Friedman test was 0.0016, and the null hypothesis was rejected. In the Scheffé test, the greatest occlusal force (the median) increased significantly six months later (97.3 N) compared with that at the baseline of jaw ROM exercise(73.8 N) (p = 0.005) and two months later (76.8 N) (p 0.02) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in greatest occlusal force at the baseline and after two, four, and six months of jaw ROM exercise. The greatest occlusal force after six months of jaw ROM exercise significantly increased compared with that at the baseline (p = 0.005), and after two months (p = 0.02). The bold line of a box plot shows the median, the upper end shows 75% and the bottom end shows 25%.

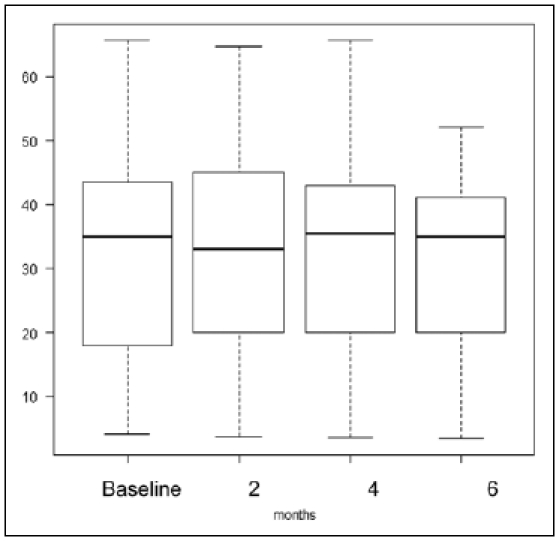

The maximum degrees of mouth opening (mean ± SD mm) at the baseline and after two, four and six months of the jaw ROM exercise were 32.1 ± 17.7 mm, 33.0 ± 17.1 mm, 32.1 ± 17.1 mm, and 31.3 ± 14.7 mm, respectively. The p value in the Friedman test of the maximum degree of mouth opening was 0.54, and the null hypothesis was not used for the Scheffé test because it was not rejected (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in maximum degree of mouth opening at the baseline, and after two, four, and six months of jaw ROM exercise; no significant change was found. The bold line of the box plot shows the median, the upper end shows 75% and the bottom end shows 25%.

By the jaw ROM exercise for six months, the greatest occlusal force increased significantly, but the maximum degree of mouth opening did not change. The patient told us, "I do not get tired from biting, and I can eat more kinds of food than before."

Discussion

This is the first report on the increase of the occlusal force of DMD patients. The jaw ROM exercise gave the DMD patients a feeling of satisfaction with their appetite. This means that the applicability of jaw ROM exercise was confirmed subjectively and objectively.

Occlusal force increases up to approximately 20 years of age in healthy persons. In the natural history of DMD, occlusal force does not increase in patients in their teens or older (2). On the basis of this finding, we did not compare the training effect between the groups of patients with and without the jaw ROM exercise, but we compared the effect in terms of the time course.

The occlusal force of DMD patients is markedly lower than that in healthy persons of the same age (5). Muscles contributing to the occlusion of the mouth are the masseter, temporal muscle, and medial pterygoid muscle. The masseter acts mainly to generate occlusal force. The factors causing the degradation of occlusal force are muscle atrophy, muscle and soft tissue consolidation (7, 10), and malocclusion (11, 12). Among these factors, we consider that the effect of the jaw ROM exercise is mainly on the amelioration of the consolidation of the masseter and soft tissue.

In this study, we applied a hot pack on the cheek of the masseter muscle region and massaged the masseter before the jaw ROM exercise. These actions were useful to reduce the consolidation of the masseter and soft tissue.

The hot pack enhances hypodermal blood flow by warming the body surface and increases the intramuscular temperature in a deep part of hypodermal tissue (13). It is confirmed that the temperature of the muscle depends on hypodermal thickness (14). In the case of DMD, the hypodermal tissue is thin, and the temperature of the masseter increases sufficiently to increase the blood flow in the masseter and soft tissue. Then, the extensibility of the masseter and soft tissue increases (15, 16), and the muscle softens (17, 18).

The masseteric massage performed immediately after a hot pack application also increased the extensibility of the masseter and soft tissue around the muscle (15, 16). The increase in the extensibility of the masseter augmented muscle force: as a result, the greatest occlusal force increases. The self-training served to maintain the effect.

In animal experiments, it was observed that there is a muscle force augmentation effect when we let an animal exercise after a hot pack application (13, 19). It is considered that the heat shock protein increased muscle protection from heat load other than blood flow improvement, which contributes to muscle force augmentation (20, 21). In DMD, a similar muscle protection may have been provided by a hot pack. Using muscle imaging, it is possible to observe changes of muscle. However, because of the physical condition of the patients, it was difficult to carry out such an imaging.

Among the outcomes, the maximum degree of mouth opening did not change significantly. The muscle contributing to the mouth opening is the lateral pterygoid muscle that is located in the deeper muscles. Thus, non-efficacy of the treatment may be due to the difficulty in intervention to the muscle from the body surface with hot pack and massage.

Taken together, we consider that the jaw ROM exercise improved the symptom of muscular disuse or underuse. For the masseter, the jaw ROM exercise is a suitable intervention for strategy as muscle atrophy progresses. It is a future problem whether we can expect a further increase or maintain the greatest occlusal force by continuing the jaw ROM exercise for more than six months.

Conventionally, in the course of DMD, occlusal muscle weakness develops 2 years earlier than perioral muscle weakness (22). From the results of this study, we suggest that we should begin this jaw ROM exercise when patients are in their teens.

Conclusions

Jaw ROM exercise in DMD increases the greatest occlusal force.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by intramural Research Grant (20B-12) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP.

References

- 1.Botteron S, Verdebout CM, Jeannet PY, et al. Orofacial dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nozaki S, Umaki Y, Sugishita S, et al. Videofluorographic assessment of swallowing function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2007;47:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanayama K, Liu M, Higuchi Y, et al. Dysphagia in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy evaluated with a questionnaire and videofluorography. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:517–522. doi: 10.1080/09638280701355595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leopold NA, Kagel MC. Swallowing, ingestion and dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:371–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueki K, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto E. Bite force and maxillofacial morphology in patients with Duchenne-type muscular dystrophy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuyuki T, Kitahara T, Nakashima A. Developmental changes in craniofacial morphology in subjects with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:42–50. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto S, Morinushi T, Ogura Ogura. Time dependent changes of variables associated with malocclusion in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002;27:53–61. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.27.1.8w14853220g47593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J Amer Statist Assoc. 1937;32:675–701. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheffé H. A method for judging all contrasts in the analysis of covariance. Biometrika. 1953;40:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiliaridis S, Katsaros C. The effects of myotonic dystrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy on the orofacial muscles and dentofacial morphology. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:369–374. doi: 10.1080/000163598428347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morel-Verdebout C, Botteron S, Kiliaridis S. Dentofacial characteristics of growing patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a morphological study. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:500–507. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Symons AL, Townsend GC, Hughes TE. Dental characteristics of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. ASDC J Dent Child. 2002;69:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren CG, Lehmann JF, Koblanski JN. Elongation of rat tail tendon: effect of load and temperature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1971;52:465–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrofsky JS, Laymon M. Heat transfer to deep tissue: the effect of body fat and heating modality. J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33:337–348. doi: 10.1080/03091900802069547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehmann J, Masock A, Warren C. Effect of therapeutic temperatures on tendon extensibility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1970;51:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee GP, Ng GY. Effects of stretching and heat treatment on hamstring extensibility in children with severe mental retardation and hypertonia. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:771–779. doi: 10.1177/0269215508090067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountain FP, Gersten JW, Sengir O. Decrease in muscle spasm produced by ultrasound, hot packs, and infrared radiation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1960;41:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer M, Schäfer SS. Temperature effects on the discharge frequency of primary and secondary endings of isolated cat muscle spindles recorded under a ramp-and-hold stretch. Brain Res. 1999;840:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi A, Ookawara T, Shimada T. Inhibitory effect of a combination of thermotherapy with exercise therapy on progression of muscle atrophy. J Physical Therapy Science. 2010;22:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz M, Robinson SD. Heat shock proteins and the heat shock response during hyperthermia and its modulation by altered physiological conditions. Prog Brain Res. 2007;162:433–446. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)62021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maglara AA, Vasilaki A, Jackson MJ, et al. Damage to developing mouse skeletal muscle myotubes in culture: protective effect of heat shock proteins. J Physiol. 2003;548:837–846. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckardt L, Harzer W. Facial structure and functional findings in patients with progressive muscular dystrophy (Duchenne) Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]