Abstract

The cellular constituents forming the haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche in the bone marrow are unclear, with studies implicating osteoblasts, endothelial and perivascular cells. Here we demonstrate that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), identified using nestin expression, constitute an essential HSC niche component. Nestin+ MSCs contain all the bone-marrow colony-forming-unit fibroblastic activity and can be propagated as non-adherent ‘mesenspheres’ that can self-renew and expand in serial transplantations. Nestin+ MSCs are spatially associated with HSCs and adrenergic nerve fibres, and highly express HSC maintenance genes. These genes, and others triggering osteoblastic differentiation, are selectively downregulated during enforced HSC mobilization or β3 adrenoreceptor activation. Whereas parathormone administration doubles the number of bone marrow nestin+ cells and favours their osteoblastic differentiation, in vivo nestin+ cell depletion rapidly reduces HSC content in the bone marrow. Purified HSCs home near nestin+ MSCs in the bone marrow of lethally irradiated mice, whereas in vivo nestin+ cell depletion significantly reduces bone marrow homing of haematopoietic progenitors. These results uncover an unprecedented partnership between two distinct somatic stem-cell types and are indicative of a unique niche in the bone marrow made of heterotypic stem-cell pairs.

The identity of the cells forming the HSC niche remains unclear. Previous studies have shown that osteolineage cells control the niche size1–3 and HSCs have been found preferentially localized in the endosteal region2,4–10. However, haematopoiesis can be sustained in extramedullary sites and selective osteoblast depletion11,12 or expansion13 does not acutely affect HSC numbers. HSCs have also been located preferentially in perivascular regions14, near reticular cells that express high levels of the chemokine CXCL12 (also called SDF-1)15. However, the identity and function of these cells have not been clearly defined.

The movement of HSCs may provide an insight into their niche because it is directly regulated by the microenvironment. HSC mobilization requires signals from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)16,17, which under homeostasis lead to clock-controlled rhythmic oscillations of Cxcl12 expression through the β3-adrenergic receptor (β3-AR, encoded by Adrb3)18. Sympathetic fibres in the bone marrow are associated with blood vessels and adventitial reticular cells connected by gap junctions, thereby forming a structural network called the neuro-reticular complex19. Here we have studied the stromal elements involved in this complex.

Nestin identifies rare SNS-innervated perivascular stromal cells

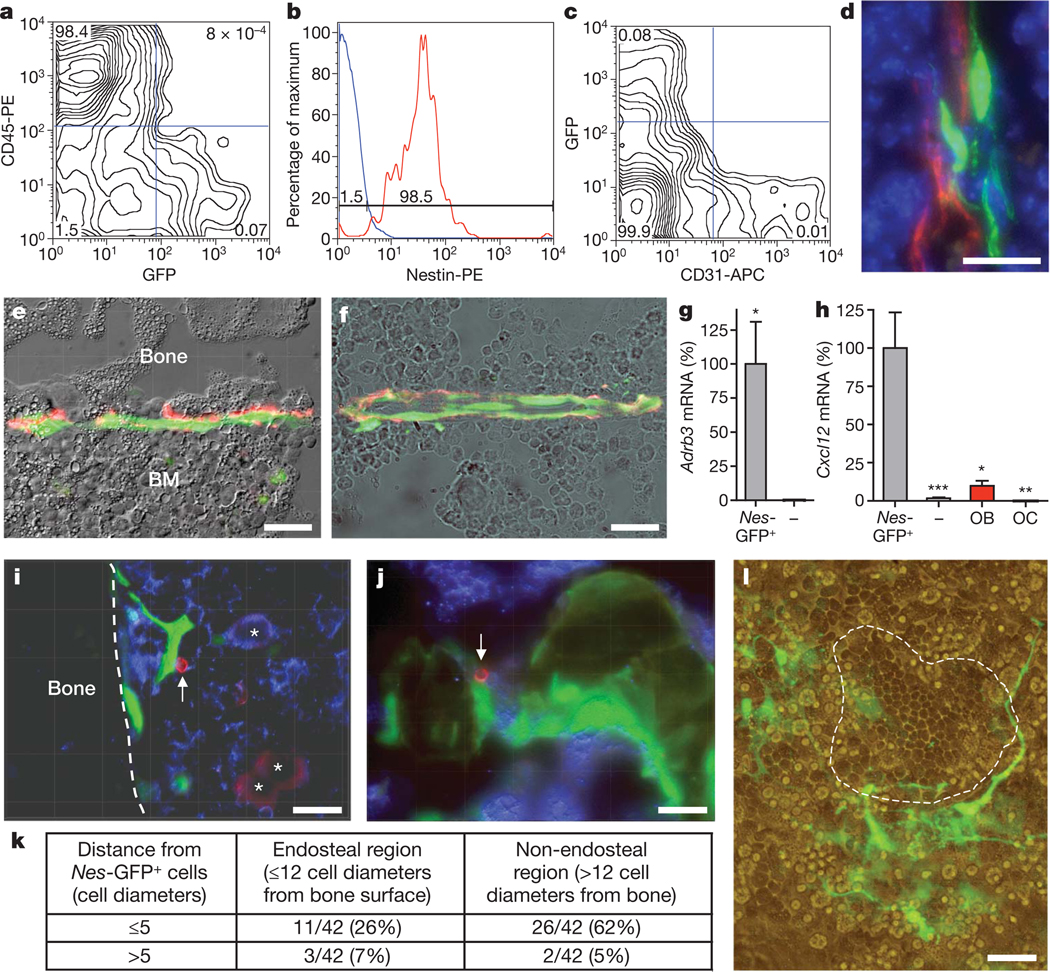

Through unrelated investigations, we have noted that bone marrow cells expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the regulatory elements of the nestin promoter20 (hereafter referred to as Nes-GFP+ cells) were relatively rare non-haematopoietic cells (4.0 ± 0.6% of the stromal CD45− population), representing a small subset of nucleated cells (0.08 ± 0.01% by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS); 0.044 ± 0.001% by histology; Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Nes-GFP+ cells also expressed the intermediate filament protein nestin (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2) and were distinct from vascular endothelial cells because they did not express CD31 (also called PECAM) (Fig. 1c, d), CD34 or VE-cadherin (data not shown). However, they showed exclusively a perivascular distribution (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3) in regions adjacent to the bone (Fig. 1e) or within the bone marrow parenchyma (Fig. 1f). Catecholaminergic nerve fibres were closely associated with Nes-GFP+ cells (Fig. 1e, f, red staining; Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, Adrb3 expression was highly enriched in CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells (Fig. 1g). Cxcl12 expression was >50-fold higher in Nes-GFP+ than in CD45− Nes-GFP− cells, tenfold higher than in primary osteoblasts and undetectable in osteoclasts (Fig. 1h). Expression of angiopoietin-1 was also several-fold higher in Nes-GFP+ cells than in CD45− Nes-GFP− cells or mature osteoblasts (Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, these results indicated that Nes-GFP+ cells met the requirements (for example, innervated cell expressing Cxcl12)18 for a candidate stromal cell regulating steady-state HSC traffic.

Figure 1. Nes-GFP+ cells are perivascular stromal cells targeted by the SNS, express high levels of Cxcl12 and are physically associated with HSCs.

a–c, Flow cytometry characterization of bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells; representative diagrams were obtained from bone marrow nucleated cells (a, c) or GFP+ cells (b); the percentage of the population in each quadrant is indicated. d, Projection image from ~10 µm Z-stack showing fluorescent signals from Nes-GFP (green), CD31+ vascular endothelial cells (red) and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). e, f, Nes-GFP+ cells are directly innervated by tyrosine hydroxylase+ (red) catecholaminergic fibres in the endosteum (e) and the bone marrow parenchyma (f). g, h, Q-PCR from the same number of sorted CD45− Nes-GFP+ and CD45− Nes-GFP− cells, and from primary osteoblasts (OB) and osteoclasts (OC; n = 5–10); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed t-test. Error bars indicate s.e.m. i, j, Immunostaining for CD150 (red), CD48 and haematopoietic lineages (blue) in femoral sections of Nes-Gfp mice. Stacked images of CD150+CD48−Lin− cells (arrow) adjacent to Nes-GFP+ cells in the endosteum (i) and the sinusoids (j). i, CD150+CD48+/Lin+ megakaryocytes (asterisks). k, Localization and number of CD150+CD48−Lin− cells relative to Nes-GFP+ cells in different bone marrow regions. l, Nes-GFP+ cells (green) and cobblestone-forming area (dashed line) in 4-week primary myeloid culture. e, f, l, Overlapped fluorescence and phase contrast images. All scale bars, 50 µm.

Nestin+ cells co-localize with HSCs in the bone marrow

To evaluate the spatial relationships between Nes-GFP+ cells and HSCs, we immunostained femoral sections of Nes-Gfp transgenic mice for haematopoietic lineage markers (anti-Ter119, Gr-1, CD3e, B220 and Mac-1), CD48 and CD150. In agreement with previous studies14, CD150+CD48−Lin− HSCs represented a very rare subset (~0.005%) of bone marrow nucleated cells. Despite the rarity of both HSCs and Nes-GFP+ cells, the vast majority (88%; 37 out of 42) of CD150+CD48−Lin− cells were located within five cell diameters from Nes-GFP+ cells, and most (60%; 25 out of 42) were directly adjacent to Nes-GFP+ cells outside (62%) or within (26%) the endosteal region (Fig. 1i–k and Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). This co-localization was highly significant (P < 10−16; Supplementary Fig. 8). In long-term bone marrow cultures, very few Nes-GFP+ cells contributed to the adherent stromal layer, but were frequently associated with cobblestone-forming areas enriched in haematopoietic progenitors (Fig. 1l). Thus, there is a close physical association between Nes-GFP+ cells and HSCs in the bone marrow.

Nestin+ cells are mesenchymal stem cells

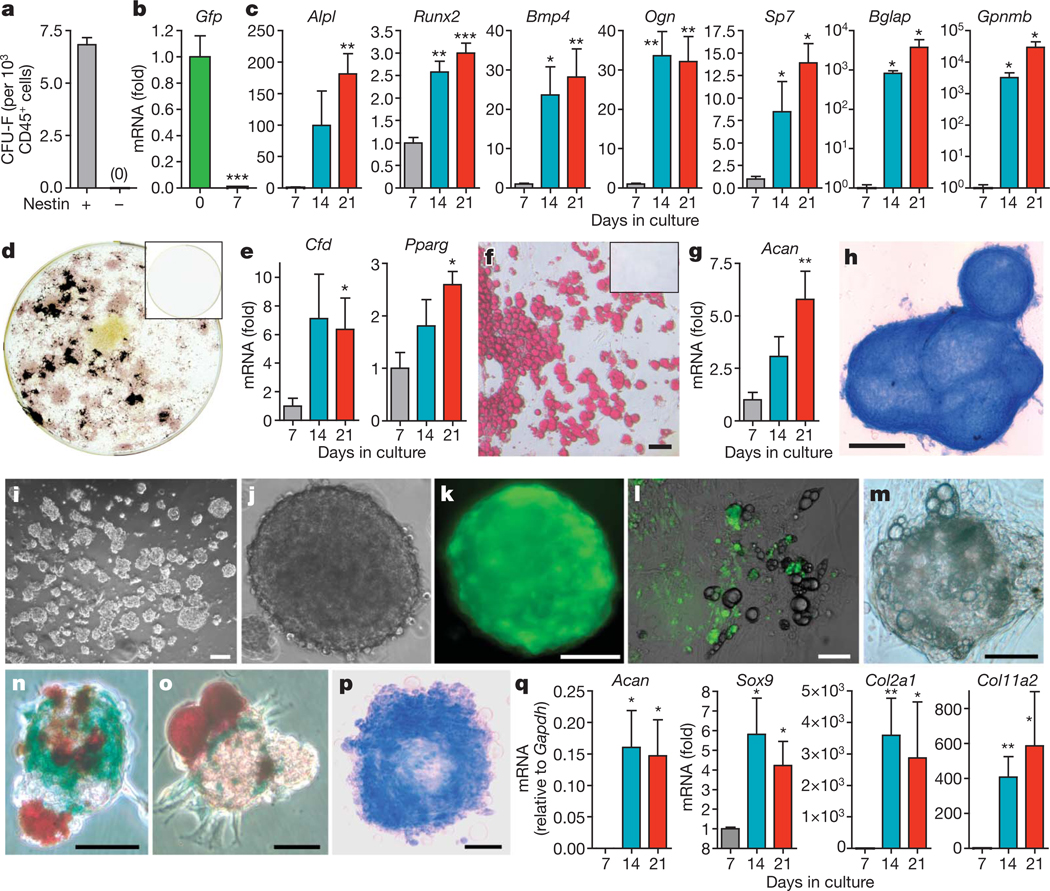

Our previous studies have indicated that CXCL12-producing bone marrow stromal cells innervated by the SNS may be osteoprogenitors18. In addition, other studies have reported that perivascular human CD45−CD146+ cells contain MSC activity21,22, and recent data indicate that cells capable of endochondral ossification are required for HSC niche formation in the fetal bone marrow23. On the basis of this and the characteristic nestin expression in neuroectoderm stem cells20,24, we hypothesized that bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells might be MSCs. Indeed, the entire mesenchymal activity and clonogenicity of CD45− cells reside within the Nes-GFP+ subset (Fig. 2a). In adherent culture, the cells rapidly lost GFP expression (Fig. 2b) and differentiated into mesenchymal lineages, as shown by progressive upregulation of osteoblastic (Fig. 2c), adipocytic (Fig. 2e) and chondrocytic (Fig. 2g) differentiation genes and a mature phenotype after 1month in culture (Fig. 2d, f, h), whereas CD45− Nes-GFP− cells did not generate any progeny.

Figure 2. Nes-GFP+ cells are mesenchymal stem cells.

a, Number of colony-forming units-fibroblast41 (CFU-F) in sorted CD45− Nes-GFP+ and CD45− Nes-GFP− cells (n = 12). b–h, Differentiation of sorted CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells (n = 4). Q-PCR of Gfp and (b) genes associated with osteoblastic (c; alkaline phosphatise (Alpl), Runx2, bone morphogenetic protein-4 (Bmp4), osteoglycin (Ogn), osterix (Sp7), osteocalcin (Bglap), osteoactivin (Gpnmb)), adipogenic (e; adipsin (Cfd), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 (Pparg)) and chondrogenic (g; aggrecan (Acan)) differentiation is shown. d, f, h, Fully differentiated phenotypes of sorted CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells shown by alkaline phosphatase (pink) and Von Kossa (black) staining (d), Oil redO (red) staining (f) and Alcian blue (blue) staining (h). CD45−Nes-GFP− cells did not generate any progeny (d, f; inset). i–q, Nes-GFP+ cells, but not the remaining CD45− bone marrow population, formed self-renewing and multipotent clonal spheres after 7–10 days in low-density culture. l, m, Adherent bulk-cultured CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells (l) or clonal spheres (m) lost GFP expression and differentiated into GFP− adipocytes (refringent lipoid droplets). n, o, Representative mesenspheres showing spontaneous multilineage differentiation into Col2.3-LacZ+ osteoblasts (blue) and Oil red O+ adipocytes (red). p, q, Chondrogenic differentiation of mesenspheres shown by Alcian blue staining (p; blue) and Q-PCR for sex determining region Y-box 9 (Sox9), aggrecan (Acan), collagen type IIα1 (Col2α1) and collagen type XIα2 (Col11α2) (n = 4–11) (q). i, j, m, p, Bright field; k, Fluorescence. l, Overlapped fluorescence and bright field. Scale bars: 100 µm (f, l, k, n, p); 500 µm (h); 50 µm (l, m, o). Asterisks, where indicated, are: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed t-test. All error bars indicate s.e.m.

Nestin+ cells form multipotent, self-renewing mesenspheres

Because neural stem cells expressing nestin can self-renew when cultured as non-adherent spheres25, we adapted conditions from neural crest26 and pericyte27 culture to expand Nes-GFP+ cells. Bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells, but not CD45− Nes-GFP− cells, formed clonal spheres with a frequency similar to neural-crest-derived stem cells28 when plated at low density (6.5 ± 0.7%) or by single-cell deposition (6.9 ± 0.7%; Fig. 2i–k). Nes-GFP+ mesenchymal spheres, hereafter referred to as mesenspheres, were 85 ± 6 µm in diameter and generated 4.4 ± 0.8 secondary spheres after dissociation (n = 19). After 2 weeks in culture, clonal mesenspheres, like bulk cultures (Fig. 2l), progressively lost GFP expression and spontaneously differentiated into mesenchymal lineages (Fig. 2m). To study their differentiation potential, we intercrossed Nes-Gfp transgenic mice with a line expressing the Cre recombinase under the osteoblast-specific 2.3-kilobase proximal fragment of the α1(I)-collagen promoter (Col2.3-cre)29 and the ROSA26/loxP-stop-loxP-lacZ30 (R26R) reporter line. After 2 weeks in culture, clonal mesenspheres obtained from triple-transgenic animals exhibited spontaneous multilineage differentiation into Oil red O+ adipocytes and osteoblasts unambiguously identified by Col2.3-driven β-galactosidase activity (~53%; 27 out of 51; Fig. 2n, o). Under conditions that favour chondrogenic differentiation, clonal mesenspheres that had previously shown adipogenic potential accumulated Alcian blue+ mucopolysaccharides (Fig. 2p) and upregulated genes involved in chondrocytic differentiation (Fig. 2q). These data demonstrate that Nes-GFP+ mesenspheres are self-renewing and multipotent in vitro.

Nestin+ MSCs self-renew in serial transplantations

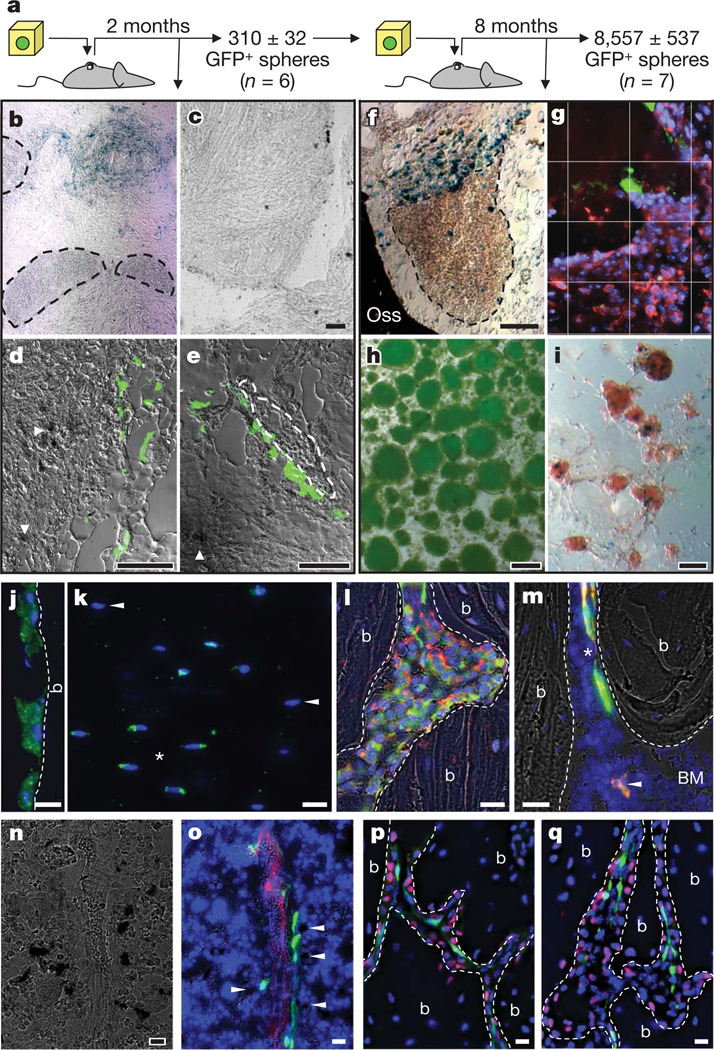

To study in vivo self-renewal, single spheres derived from triple-transgenic animals were allowed to attach onto phosphocalcic ceramic ossicles and then implanted subcutaneously into littermate mice that did not carry the transgenes (Fig. 3a). Ossicles harvested after 2 months contained numerous β-galactosidase+ osteoblasts derived from Nes-GFP+ cells (Fig. 3b, d, e), whereas the seeding of 30,000 CD45− Nes-GFP− cells did not generate β-galactosidase+ cells (Fig. 3c). Nes-GFP+ cells were often associated with haematopoietic activity in the ossicles (Fig. 3b, e). Enzymatic digestion yielded 310 ± 32 new GFP+ spheres per ossicle (n = 6), 38.6 ± 1.9% of which showed multilineage differentiation (Supplementary Table 1). These secondary spheres were subsequently implanted into secondary recipients (Fig. 3a). Numerous Col2.3+ (hence donor-derived) osteoblasts (Fig. 3f) and haematopoietic activity (Fig. 3g; confirmed by CD45 immunostaining) were observed in contact with Nes-GFP+ cells in secondary ossicles harvested after 8 months. Notably, ~8,500 GFP+ spheres were recovered from each secondary ossicle (Fig. 3h), indicating robust in vivo self-renewal. These GFP+ spheres also generated Col2.3+ osteoblasts (Fig. 3i), a further proof of their mesenchymal differentiation potential and donor origin. Thus, these results demonstrate that nestin+ cells are indeed bona fide MSCs capable of self-renewal in serial transplantations.

Figure 3. Adult nestin+ MSCs self-renew, differentiate and transfer haematopoietic activity in vivo.

a–i, In vivo self-renewal of adult bone marrow CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells in secondary transplants. a, Scheme showing the experimental paradigm. b–e, Primary ossicles showing numerous β-galactosidase+ osteoblasts derived from CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells (b, blue; d, e, dark deposits, arrowheads) but none from CD45− Nes-GFP− cells (c); haematopoietic areas (b, e; circled by dashed line) were detected only in the former group and frequently associated with GFP+ cells (e, green). f, Secondary ossicle showing numerous β-galactosidase+ osteoblasts derived from CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells (blue) and also haematopoietic areas (circled by dashed line). g, CD45+ haematopoietic cells (red) localized near Nes-GFP+ (green) cells in the ossicles; cell nuclei have been stained with DAPI (blue); grid, 50 µm per square. h, i, Secondary ossicles yielded 8,557 ± 537 GFP+ spheres (h) that generated Col2.3+ osteoblasts (i; blue precipitates). j–m, Adult nestin+ MSCs contribute to endochondral lineages. j–l, Femoral sections from 11-month-old Nes-creERT2/RCE:loxP double-transgenic mice 8 months after tamoxifen treatment showing the contribution of adult nestin+ cells to bone-lining osteoblasts (j), osteocytes (k; asterisks indicate GFP+ cells, arrowheads indicate GFP− osteocytes) and collagen α1 type 2+ (red) chondrocytes (l). m, GFP+ (green) perivascular cells (asterisk) identical in frequency, morphology and distribution to Nes-GFP+ cells and osteoblasts (arrowhead) co-stained with anti-GFP antibodies (red). n, o, Bone marrow section of Nes-Gfp/Col2.3-cre/R26R triple-transgenic mouse showing X-gal+ osteoblasts (dark precipitates), GFP+ (green) and CD31+ vascular endothelial cells (red); Col2.3+ osteoblasts localized near Nes-GFP+ perivascular cells are indicated with arrowheads. p, q, Immunostaining for osterix (red) in trabecular bone section of a 5-week-old Nes-Gfp (green) mouse. g, j–m, o–q, Nuclei have been stained with DAPI (blue). j, l,m, p, q, Bone (b) margins are indicated with dashed lines. b, c, f, i, n, Bright field; g, j, k, p, q, fluorescence; d, e, h, l, m, o, overlapped fluorescence and bright field. Scale bars: 100 µm (c–f, h, i); 20 µm (j–q).

Physiological contribution to osteochondral lineages

We carried out lineage-tracing studies to evaluate whether nestin-expressing MSCs contribute physiologically to skeletal formation. Analyses of R26R mice intercrossed with a transgenic line expressing the Cre recombinase under Nes regulatory elements (Nes-cre)31 revealed the contribution of nestin+ cells to osteoblasts, osteocytes and chondrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 9). To track more specifically the progeny of adult nestin+ MSCs, we intercrossed the conditional transgenic line Nes-creERT2 (ref. 32) with RCE:loxP transgenic mice33. Consistent with a slow turnover of the skeleton, we could not detect GFP+ bone-forming cells after a 1-month chase. However, GFP+ osteoblasts, osteocytes and chondrocytes were observed after 8 months (Fig. 3j–m). These results indicate that adult nestin+ MSCs contribute to skeletal remodelling through differentiation into cartilage- and bone-forming cells.

Because pre-osteoblasts and mature osteoblasts have been associated with HSCs in the bone marrow2,4,5,10, we also studied their relationship with Nes-GFP+ MSCs. Col2.3+ mature osteoblasts were distinct from, but frequently localized near, Nes-GFP+ perivascular MSCs (Fig. 3n, o). N-cadherin+ cells were largely bone-lining osteoblasts and pre-osteoblasts, as previously reported10, distinct from Nes-GFP+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 10). Cells expressing osterix, a transcription factor required during osteoblastic differentiation34, were also significantly more abundant than Nes-GFP+ MSCs in the trabecular bone and were localized between Nes-GFP+ cells and the bone margin (Fig. 3p, q), with a ratio of Nes-GFP+/osterix+ cells in keeping with that of stem cell/progenitor. Therefore, despite their osteoblastic differentiation potential, Nes-GFP+ MSCs are distinct from pre-osteoblasts and osteoblasts.

Nestin+ MSCs are quiescent and metabolically active

Nestin expression and sphere-forming capacity suggested a neuroectodermal origin of these MSCs. Indeed, the presence of multipotent bone-marrow neural-crest-derived cells has been suggested35 and Sox1+ neuroepithelial cells supply the first embryonic MSC wave36. To get a molecular signature of bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells, we have compared their genome profile with various stem cells obtained from public databases. Non-biased hierarchical clustering and principal coordinates analyses revealed that bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells were different from all stem cells analysed. However, in agreement with their MSC function, their overall expression profile appeared closest to human MSCs (Supplementary Fig. 11a, e).

We performed gene ontology analyses and predicted protein–protein interactions from transcripts significantly up- or downregulated in bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells compared to all stem cells analysed. Most upregulated transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 11b, d) were associated with metabolic processes (cyan nodes), whereas most downregulated transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d) were involved in cell cycle progression (yellow nodes).

Differential effects of G-CSF, SNS and parathormone

Previous studies indicate that the haematopoietic cytokine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) inhibits osteoblasts37 through the SNS16. By contrast, in vivo parathormone administration expanded osteoblasts and also doubled the HSC pool1,3. We investigated how these physiological stimuli affected the proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells. Cell cycle studies confirmed that bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells are significantly more quiescent than other stromal CD45− Nes-GFP− cells. Within the CD45− population from flushed bone marrow samples, the proliferative fraction of Nes-GFP+ cells was significantly greater after chemical sympathectomy or parathormone administration. In contrast, G-CSF treatment inhibited proliferation of both Nes-GFP+ and CD45− Nes-GFP− cells (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b).

The inhibitory effects of the SNS and G-CSF on bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells did not only concern the cell cycle but also differentiation, as G-CSF, a non-selective β- or a selective β3-AR agonist downregulated osteoblastic differentiation genes specifically in Nes-GFP+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d). By contrast, in vivo parathormone administration increased by ~2-fold the number of bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 12e) and primed them to differentiate more rapidly (<1 week) into Col2.3+ osteoblasts (Supplementary Fig. 12f, g). The effect of parathormone was direct because it was also observed in vitro in purified bone marrow Nes-GFP+ cells, which express parathormone receptor (Supplementary Fig. 13). These results raise the possibility that HSC expansion previously associated with parathormone administration1,3 could be due to expansion of nestin+ MSCs rather than mature osteoblasts.

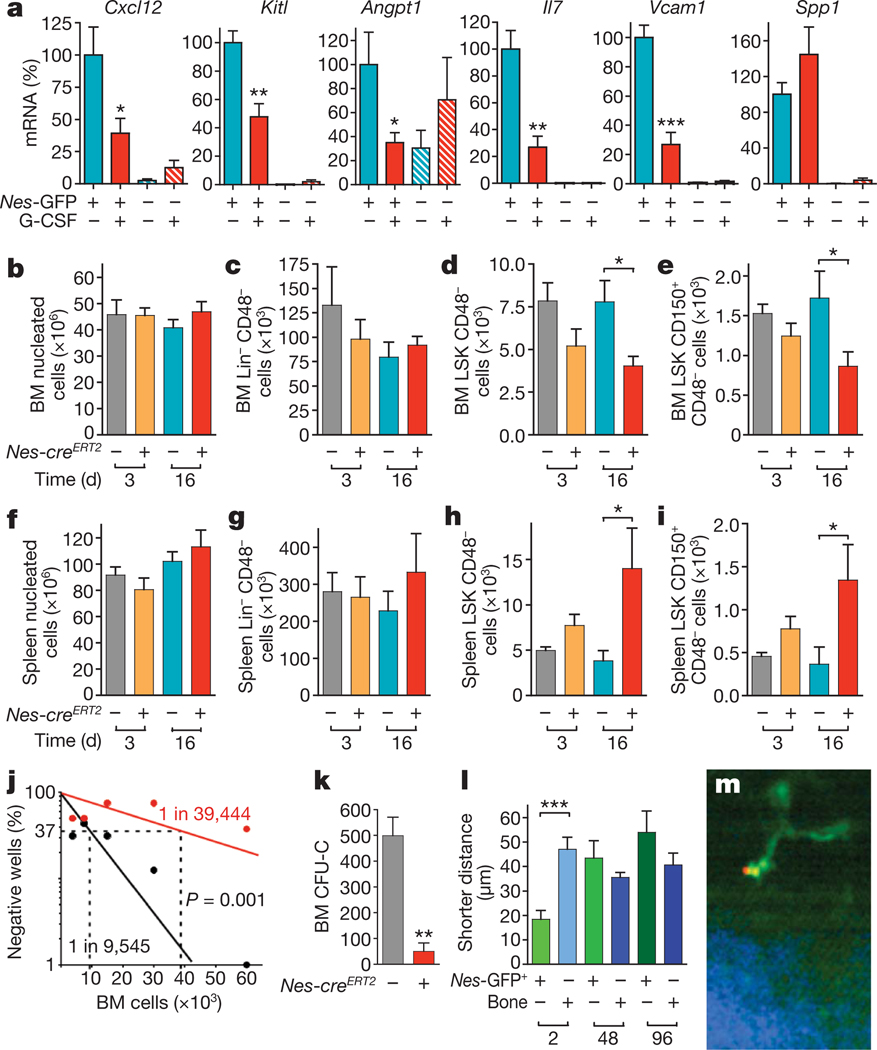

Expression and regulation of HSC maintenance genes

To gain more insight into the regulation of the HSC niche by G-CSF and the SNS, we analysed the expression of genes that regulate HSC maintenance and attraction in the bone marrow38 (Cxcl12, c-kit ligand, angiopoietin-1, interleukin-7, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and osteopontin) in mice treated with G-CSF or β-AR agonists. The expression of these genes was extremely high (close to or higher than Gapdh) in Nes-GFP+ cells, and—with the exception of Angpt1—50–700-fold higher than in the other bone marrow stromal cells. Moreover, these genes, except osteopontin, were significantly and selectively downregulated in Nes-GFP+ cells by G-CSF (Fig. 4a) or β3-AR agonists (Supplementary Fig. 14a). Very similar results were obtained when β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene instead of Gapdh (Supplementary Fig. 15). The expression of connexin-45 and connexin-43 was also 200–500-fold higher in Nes-GFP+ cells than in CD45− Nes-GFP− cells (Supplementary Fig. 14b), indicating the existence of electromechanical coupling involving nestin+ cells innervated by noradrenergic nerve terminals16,18,19.

Figure 4. Regulation of HSC maintenance by nestin+ MSCs.

a, Expression and regulation of core HSC maintenance genes by CD45− Nes-GFP+ cells. Q-PCR for Cxcl12, stem cell factor/kit ligand (Kitl), angiopoietin-1 (Angpt1), interleukin-7 (Il7), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (Vcam1) and osteopontin (Spp1) in CD45− Nes-GFP+ and CD45− Nes-GFP− cells sorted from the bone marrow of mice injected with G-CSF or vehicle (n = 6). b–k, Bone marrow (BM) and spleen nucleated (b, f), Lin− CD48− (c, g), CD48− LSK (d, h) and CD150+CD48− LSK (e, i) cells 3–16 days after tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin administration in Nes-creERT2/iDTR double- and control iDTR single-transgenic mice (n = 6–12). j, Long-term culture-initiating cell assay using limiting dilutions of bone marrow cells from Nes-creERT2/iDTR (red) or control iDTR mice (black) 1 month after tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin treatment; the percentage of culture dishes in each experimental group that failed to generate colony-forming units is plotted against the number of test bone marrow cells; bone marrow HSC frequencies are indicated; Pearson chi-squared test (n = 4–6). k–m, Nestin+ cells are required for the homing of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. k, Bone marrow homing of haematopoietic progenitors (CFU-C) in tamoxifen- and diphtheria-toxin-treated Nes-creERT2/iDTR and control iDTR mice (n = 4–8). l, m, HSCs rapidly home near GFP+ cells in the bone marrow of Nes-Gfp transgenic mice. l, Average shorter distances between bone marrow HSCs, Nes-GFP+ cells and the bone surface 2 h (n = 16), 48 h (n = 30) and 96 h (n = 14) after HSC transplantation into lethally irradiated mice. m, Representative DyD-stained (red) HSC, Nes-GFP+ (green) cell and bone matrix (blue). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed t-test. All error bars indicate s.e.m.

Nestin+ cells maintain HSCs in the bone marrow

To determine whether nestin+ cells are required for HSC maintenance in the bone marrow, we performed selective depletion experiments by intercrossing a Cre-recombinase-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor line39 (iDTR) with Nes-creERT2 mice. In adult Nes-creERT2/iDTR mice, tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin treatment severely reduced bone marrow nestin+ cells, as estimated by mesensphere-forming efficiency (92.9 ± 1.8% reduction; n = 6). Whereas bone marrow cellularity and Lin−CD48− cell numbers were not affected in Nes-creERT2/iDTR mice up to 2 weeks after treatment with diphtheria toxin (Fig. 4b, c), the more immature CD48−Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ (LSK) cells (Fig. 4d) and CD150+ CD48− LSK cells (Fig. 4e) were reduced by ~50%. This was associated with a proportional and selective increase in the number of LSK and CD150+CD48− LSK cells in the spleen (Fig. 4f–i), without detectable difference in cell cycle profile or apoptotic rates (Supplementary Fig. 16). Moreover, long-term culture-initiating cell (LT-CIC) assay using limiting dilutions of bone marrow cells obtained from Nes-creERT2/iDTR double transgenic or control iDTR mice 1 month after tamoxifen and diphtheria toxin treatment showed a ~4-fold reduction in bone marrow HSC activity after depletion of nestin+ cells (Fig. 4j). Thus, these studies indicate that HSCs/progenitors are reduced in the bone marrow after the depletion of nestin+ cells, owing at least in part to mobilization towards extramedullary sites.

Nestin+ cells are required for HSC/progenitor homing

To evaluate further the impact of nestin+ cells in progenitor trafficking to bone marrow, we assayed haematopoietic progenitor homing to the bone marrow, and found it to be markedly reduced (by 90%) in diphtheria-treated, lethally irradiated Nes-creERT2/iDTR mice (Fig. 4k). To assess more specifically the homing of HSCs, we tracked by intravital microscopy highly purified, fluorescently labelled HSCs after transplantation into lethally irradiated Nes-Gfp transgenic mice, as described40. Calvarial Nes-GFP+ cells were also perivascular (Supplementary Fig. 17), contained all colony-forming units-fibroblast (CFU-F) and sphere-forming cells (data not shown). Analyses of average shorter distances of homed HSCs from Nes-GFP+ cells and the bone surface revealed that HSCs rapidly home near Nes-GFP+ cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 4l, m), indicating that bone marrow nestin+ cells participate in directed HSC migration.

Discussion

These studies indicate that nestin+ cells represent bona fide niche cells in that they show a close physical association with HSCs, very high expression levels of core HSC maintenance genes, selective down-regulation of these genes by G-CSF or β3-AR stimulation, and significant reductions in bone marrow HSCs upon their deletion. In addition, they behave functionally as MSCs based on their exclusive CFU-F content, multilineage differentiation towards mesenchymal lineages, robust self-renewal in serial transplantation and in vivo contribution to osteochondral lineages under homeostasis. Furthermore, we provide evidence for a balanced regulation of haematopoietic and mesenchymal lineages at the stem-cell level where homeostatic neural (for example, SNS) and hormonal (for example, parathormone) mechanisms tightly regulate in tandem HSC maintenance and MSC proliferation and differentiation.

The present studies reconcile divergent views about the cellular components of the HSC niche, because nestin+ cells encompass features previously attributed to osteoblastic1,2 or endothelial14 niches. The data indicate a structurally unique niche in the bone marrow made of MSC–HSC pairings, tightly regulated by local input from the surrounding microenvironment and by long-distance cues from hormones and the autonomic nervous system.

METHODS SUMMARY

Nes-Gfp (ref. 20), FVB-Tg(Col1a1-cre)1Kry/Mmcd (ref. 29), B6.Cg(SJL)-TgN(Nes-cre)1Kln (ref. 31), Nes-CreERT2 (ref. 32), RCE:loxP (ref. 33), C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai/J39, B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J30 transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratories) and C57BL/6-CD45.1 mice (Frederick Cancer Research Center) have been used in these studies. Detailed procedures for cell isolation and culture, in vitro differentiation, LT-CIC and heterotopic bone ossicle assays, histological analyses of ossicles, in vivo treatments and cell depletion experiments, homing assay, RNA isolation, quantitative real-time RT–PCR, gene chip and analyses of microarray experiments, gene ontology and protein–protein interactions are available in the Methods.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. García-Fernández, Y. Kunisaki, C. Scheiermann, J. Isern, E. Nistal-Villan and D. Lucas for help with some experiments; M. Kiel and S. Morrison for advice about immunohistological analysis of HSCs; C. Lin for help with intravital microscopy imaging; G. Fishell for the gift of Nes-creERT2 and RCE:loxP transgenic mice; J. Ahmed, W. Kao and J. Godbold for help with immunofluorescence and statistical analyses; S. Lymperi for advice about LT-CIC; L. Silberstein, G. Khitrov and W. Zhang for help with microarray experiments; M. Grisotto for help with cell sorting; and L. Shang, A. J. Peired and C. Prophete for help with animals. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 grants DK056638, HL69438, HL097819) and the Department of Defence (Idea Development Award PC060271) to P.S.F. and by the National Institute of Mental Health and Ira Hazan Fund to G.N.E. S.M.-F. is the recipient of a Scholar Award by the American Society of Hematology. P.S.F. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions All authors contributed to the design of experiments. S.M.-F. performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. T.V.M. and S.M.-F. performed experiments involving depletion of nestin+ cells and lineage tracing studies. F.F. performed intravital homing experiments. A.M.’a., A.R.M. and B.D.M. designed and performed analyses of microarray experiments. G.N.E., D.T.S. and S.A.L. contributed reagents and provided advice on the manuscript. P.S.F. supervised experiments and the overall study, and wrote the manuscript.

Author Information The microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the accession number GSE21941. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams GB, et al. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche. Nature Biotechnol. 2007;25:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Coverdale JA. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 2001;97:2293–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams GB, et al. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai F, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson SK, et al. Osteopontin, a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and regulator of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1232–1239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stier S, et al. Osteopontin is a hematopoietic stem cell niche component that negatively regulates stem cell pool size. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1781–1791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson A, et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Y, et al. Detection of functional haematopoietic stem cell niche using real-time imaging. Nature. 2009;457:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visnjic D, et al. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004;103:3258–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;109:3706–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lymperi S, et al. Strontium can increase some osteoblasts without increasing hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2008;111:1173–1181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Méndez-Ferrer S, Battista M, Frenette PS. Cooperation of β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors in hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2010;1192:139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki K, Allen TD. Ultrastructural morphometric study of efferent nerve terminals on murine bone marrow stromal cells, and the recognition of a novel anatomical unit: the “neuro-reticular complex”. Am. J. Anat. 1990;187:261–276. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001870306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacchetti B, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crisan M, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan CK, et al. Endochondral ossification is required for haematopoietic stem-cell niche formation. Nature. 2009;457:490–494. doi: 10.1038/nature07547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mignone JL, et al. Neural potential of a stem cell population in the hair follicle. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2161–2170. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.17.4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stemple DL, Anderson DJ. Isolation of a stem cell for neurons and glia from the mammalian neural crest. Cell. 1992;71:973–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90393-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardal R, Ortega-Saenz P, Duran R, Lopez-Barneo J. Glia-like stem cells sustain physiologic neurogenesis in the adult mammalian carotid body. Cell. 2007;131:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crisan M, et al. Purification and culture of human blood vessel-associated progenitor cells. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2008;2:2B.2.1–2B.2.13. doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc02b02s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molofsky AV, et al. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature. 2003;425:962–967. doi: 10.1038/nature02060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G. Mouse α1(I)-collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Dev. Dyn. 2002;224:245–251. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nature Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tronche F, et al. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nature Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balordi F, Fishell G. Mosaic removal of hedgehog signaling in the adult SVZ reveals that the residual wild-type stem cells have a limited capacity for self-renewal. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14248–14259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4531-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sousa VH, Miyoshi G, Hjerling-Leffler J, Karayannis T, Fishell G. Characterization of Nkx6-2-derived neocortical interneuron lineages. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19 Suppl. 1:i1–i10. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakashima K, et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagoshi N, et al. Ontogeny and multipotency of neural crest-derived stem cells in mouse bone marrow, dorsal root ganglia, and whisker pad. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takashima Y, et al. Neuroepithelial cells supply an initial transient wave of MSC differentiation. Cell. 2007;129:1377–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semerad CL, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106:3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendez-Ferrer S, Frenette PS. Hematopoietic stem cell trafficking: regulated adhesion and attraction to bone marrow microenvironment. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2007;1116:392–413. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buch T, et al. A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nature Methods. 2005;2:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nmeth762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Celso C, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.