Abstract

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) has distinct advantages over other viral vectors in delivering genes of interest to the brain. AAV mainly transfects neurons, produces no toxicity or inflammatory responses, and yields long-term transgene expression. In this study, we first tested the hypothesis that AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) selectively transfects neurons but not glial cells in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) by examining expression of the reporter gene, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), in the rat NTS after unilateral microinjection of AAV2eGFP into NTS. Expression of eGFP was observed in 1–2 cells in the NTS 1 day after injection. The number of transduced cells and the intensity of eGFP fluorescence increased from day 1 to day 28 and decreased on day 60. The majority (92.9 ± 7.0%) of eGFP expressing NTS cells contained immunoreactivity for the neuronal marker, protein gene product 9.5, but not that for the glial marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein. We observed eGFP expressing neurons and fibers in the nodose ganglia (NG) both ipsilateral and contralateral to the injection. In addition, eGFP expressing fibers were present in both ipsilateral and contralateral nucleus ambiguus (NA), caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). Having established that AAV2 was able to transduce a gene into NTS neurons, we constructed AAV2 vectors that contained cDNA for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and examined nNOS expression in the rat NTS after injection of this vector into the area. Results from RT-PCR, Western analysis, and immunofluorescent histochemistry indicated that nNOS expression was elevated in rat NTS that had been injected with AAV2nNOS vectors. Therefore, we conclude that AAV2 is an effective viral vector in chronically transducing NTS neurons and that AAV2nNOS can be used as a specific gene transfer tool to study the role of nNOS in CNS neurons.

Keywords: Adeno-associated virus, Enhanced green fluorescent protein, Gene transfer, Immunofluorescent histochemistry, Neuronal nitric oxide synthase, Nucleus tractus solitarii, RT-PCR, Western blot

Introduction

As the primary site of termination of visceral afferent inputs, the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), located in the dorsomedial medulla oblongata, is involved in central regulation of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and ventilatory functions (Kalia and Sullivan 1982; Spyer et al. 1984; Nattie 1999; Broussard and Altschuler 2000; Boscan et al. 2002). Mediation of these physiological functions relies on signal transduction governed by numerous potential neurotransmitters and modulators that are present in the NTS (Lawrence and Jarrott 1996; Bradley et al. 1996; Nattie 1999; Broussard and Altschuler 2000; Lin 2009). In recent years, in addition to pharmacological manipulation and neuroanatomical analyses, gene transfer using replication-deficient recombinant viral vectors to up- or down-regulate neurotransmitters has been used to delineate the role of some of the putative neurotransmitters in the NTS (Sakai et al. 2000; Hirooka et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006). For example, adenovirus has been used as a vector to carry the DNA sequence coding interference RNA for angiotensin receptor type 1 into the NTS and thus to down-regulate angiotension receptors. Doing so caused a decrease in blood pressure with no effect on heart rate in mouse (Chen et al. 2006). In contrast, injection into the NTS of adenovirus vector encoding endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) increased production of nitric oxide (NO) and led to decreased heart rate and blood pressure in rat (Sakai et al. 2000; Hirooka et al. 2003).

Another class of viral vector, adeno-associated virus (AAV), a non-pathogenic parvovirus, appears to be a highly promising tool for gene transfer into the brain (Van Vliet et al. 2008). Like adenovirus, AAV vectors are capable of transducing non-dividing cells and leading to efficient and stable transgene expression in the brain (Xiao et al. 1997a). However, AAV vectors possess several unique and advantageous characteristics. While adenovirus vectors often elicit a strong immune response (Yang et al. 1996; Xiao et al. 1997b) and may have cellular toxicity (Durham et al. 1996), AAV vectors have been shown to be not immunogenic and not toxic to the host tissue (Xiao et al. 1997a; Bueler 1999). In addition, in vivo gene transduction by AAV vectors lasts for a long time with some reports indicating continued transduction for months (Kaplitt et al. 1996; Xiao et al. 1996) or even a year or more (Gasmi et al. 2007; Belur et al. 2008). In contrast, adenovirus gene expression may diminish 1 month after injection (Boulis et al. 1999). Furthermore, some types of AAV vectors have been found to preferentially transfect neurons in some areas of the brain (Nomoto et al. 2003) while adenovirus may preferentially transfect non-neuronal cells in the CNS (Allen et al. 2006). What type of cell a vector transfects may be important in dissecting how a neurotransmitter system works when that vector is used to up-regulate or down-regulate a neurotransmitter in a specific group of cells. Among AAV serotypes, AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) vector has been studied extensively and has been shown to transduce neurons exclusively (Nomoto et al. 2003). This means that AAV2 would be a powerful tool in delineating the role of certain neurotransmitters such as neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), which is only found in neurons in the NTS (Lin and Talman 2005a; Lin et al. 2007), as opposed to endogenous eNOS, which is found in non-neuronal cells in the same region (Lin et al. 2007). In that both of the NOS isoenzymes are capable of producing NO and the origin of the NO could affect different physiological effects, any alteration of synthesis would optimally be directed toward the cell type that naturally synthesizes the NO involved in those effects.

AAV2 has been used as a tool for gene transfer in several regions of the brain (Gasmi et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2009). Although AAV2 was used in the rat NTS in one publication to knockdown the expression of leptin receptors (Hayes et al. 2010), it is not known what type of NTS cells are transduced and the time course of AAV2 transduction in the NTS. Therefore, the purposes of the current study were to test the hypothesis that AAV2 transduces signals in neurons, in preference to glia, in the rat NTS and to study the time course of AAV2 transduction in the NTS by using AAV2 vectors carrying the gene for enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). We also examined the nodose ganglion (NG) for evidence of transduction after injection of AAV2 vector into the NTS to determine if there is uptake and retrograde transport of the vector from the NTS to the NG, the site of sensory afferent neurons that send arterial baroreceptor, chemoreceptor, and cardiopulmonary afferent axonal projections to the NTS (Dampney 1994). Furthermore, we examined the nucleus ambiguus (NA), rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), and caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) to determine if the AAV2 vector may undergo anterograde transport from the NTS. Finally, we constructed an AAV2 vector that encoded cDNA for nNOS (AAV2nNOS) and tested the hypothesis that nNOS expression in the rat NTS can be up-regulated after injection of this vector to this area. We examined mRNA and protein levels of nNOS in the rat NTS with real time RT-PCR, Western blot analysis, and immunofluorescent histochemistry.

Methods

Viral Vectors

AAV2 vector encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (AAV2eGFP) driven by cytomegalovirus (CMV) promotor was generated and titered by the Gene Transfer Vector Core of the University of Iowa using a baculovirus system according to methods described previously (Urabe et al. 2002). The titer of vectors used in the current study was 9.68 × 1013 viral genomes/ml. The vectors were stored at −80°C in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) containing 250 mM NaCl. They were dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 4°C for 15 min immediately before use.

Rat nNOS cDNA, a gift from Dr. David S. Bredt (Bredt et al. 1991), was cloned into a modified rAAV2 packaging plasmid pFBGR (Gene Transfer Vector Core, University of Iowa, USA) with a CMV promotor. AAV2 vectors encoding nNOS cDNA (AAV2nNOS) were then prepared by a triple baculovirus infection in SF-9 insect cells by The Gene Transfer Vector Core of The University of Iowa using similar methods described above. The titer of the AAV2nNOS vector was 1.12 × 1013 viral genomes/ml. The vectors were stored at −80°C and dialyzed against PBS immediately before use as described above.

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293), which do not naturally express nNOS, were used to examine the efficiency of recombinant AAV plasmid that contained nNOS cDNA (AAVp-nNOS). HEK293 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCF, Manassas, VA, USA) and grown in six-well plate in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium and supplements with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. They were incubated with AAVp-nNOS for 48 h before they were harvested for real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Western blot analysis.

Animals and Injections

All procedures conformed to standards established in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press, Washington, DC 1996). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Iowa and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Iowa City reviewed and approved all protocols. Both institutions are AAALAC accredited. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and to avoid their experiencing pain or distress.

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (275–340 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction and 1.5–2.0% maintenance) delivered in 100% O2 (2 l/min) by a nasal mask. The dorsal surface of the brain stem was exposed as previously described (Talman 1989), and a glass micropipette filled with viral vectors was stereotactically placed (0.4 mm rostral to the calamus scriptorius, 0.5 mm from the midline, and 0.5 mm below the surface of the brain stem) unilaterally into the dorsolateral and medial subnuclear regions of the NTS at the level of the area postrema. Injections (individual increments of 25–50 nl to a combined total of 200 nl) were made over 15 min and the pipette was left in place for 15 additional minutes to limit efflux of injectate from the pipette track. Surgical wounds were closed, hemostasis assured, the animal treated with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg), and anesthesia stopped. After recovery from anesthesia, the animal was returned to the animal care facility until it was later brought to the laboratory to be euthanized. For the time course study of AAV2eGFP in the NTS, we euthanized rats under deep pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) anesthesia 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28, and 60 days after the injection (n = 2 for 1 and 2 days, n = 3 for all the other time points). For fluorescent immunohistochemical evaluation of nNOS expression in the NTS, rats (n = 4) were euthanized 2 weeks after the injection.

Procedures for euthanasia and perfusion fixation of tissues have been described in our earlier publications (Lin and Talman 2005a; 2006; Lin et al. 2007). The brain was removed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h and then cryoprotected for 2 days in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C. Frozen 20 μm coronal sections were cut with a cryostat and processed for double-label immunofluorescent staining of a glial marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and a neuronal marker, protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5), as described below. In some cases, sections were stained for PGP9.5 or nNOS alone. As previously described (Lin et al. 1998), we removed the ipsilateral and contralateral NG removed after perfusing the rat. The NG were then postfixed for 1 h, transferred to 30% sucrose overnight, cut, mounted to slides and processed for immunofluorescent staining.

For real time RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of nNOS expression, rats were bilaterally injected with AAV2nNOS (200 nl, containing 2.24 × 109 viral genomes) in the NTS as described above and were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) 2 weeks later (n = 10 for AAV2nNOS injection, n = 9 for control). The NTS was micropunched out with a stainless tubing (inner diameter of 0.038 inch or 0.96 mm) from consecutive 150 μm frozen cryostat sections. The punches were stored at −20°C until they were used for Western blot analysis or placed in cold RNAlater (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) overnight and than stored at −20°C for real time RT-PCR. Tissue from each rat was analyzed separately.

Immunofluorescent Staining

Procedures similar to those described in our previous publications (Lin and Talman 2005a; 2006; Lin et al. 2007) were used for immunofluorescent staining of brain stem and NG sections. For double-label immunofluorescent staining for PGP9.5 and GFAP, brain stem sections were incubated in a mixture of mouse anti-GFAP antibody (1:100, Sigma, USA) and rabbit anti-PGP9.5 (1:200, Chemicon, USA) in 10% donkey normal serum for 24 h in a humid chamber at 25°C. After being washed with PBS, sections were incubated with Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, USA) and rhodamine red X (RRX)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.) in PBS for 20–24 h at 4°C. The primary and secondary antibodies for GFAP were omitted when we performed fluorescent immunostaining of PGP9.5 alone. For immunofluorescent staining of nNOS alone, sheep anti-nNOS antibody (1:1000, from Dr. Piers C. Emson) (Herbison et al. 1996) was used as the primary antibody and Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-sheep IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) as the secondary antibody.

Stained sections were washed and mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagents (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, USA). Negative controls consisted of tissue processed (a) in the absence of primary antibodies or (b) after addition of only one of the primary antibodies. In addition, we have used both PGP9.5 and GFAP antibodies in our previous publications with satisfactory results (Lin et al. 2007, 2010). We also have used sheep anti-nNOS antibody in a number of previous publications (Lin and Talman 2005a; Lin et al. 2004, 2007). Stained brain stem sections and NG sections were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 or LSM 710 confocal microscope as described below.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

As we previously described (Lin and Talman 2006; Lin et al. 2007), we analyzed labeled sections with a Zeiss LSM 510 or a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope and scanned specimens sequentially with one to three channels to separate labels. For optimal visualization of the relationship between eGFP-, RRX-, Cy2-, and Cy5-labeled elements, images from three channels were assigned the pseudocolor green (for eGFP or Cy2), red (for RRX) and blue (for Cy5) respectively, and then were superimposed. Confocal images were obtained and processed with software provided with the Zeiss LSM 510 or Zeiss LSM 710. Adobe Photoshop image editing software (Adobe Photoshop CS2) was used to examine if a structure had single labeling or double labeling by switching between channels on the monitor. Another image editing program, Microsoft PowerPoint (2003), was used to create montages. Contrast and brightness of images were the only variables we adjusted digitally.

Cell Counts

Cell counts were performed in time course studies of AAV2eGFP injections. We counted stained cells in images of 3–4 selected sections at comparable levels of the brain stem (within 200 μm of the center of the injection site) from each rat. We avoided analysis of sequential sections so that sections used for counting were at least 20 μm (the thickness of the sections) apart. Therefore, we minimized the possibility that the same stained neurons would be counted twice. For multiple-label sections, labeled cells in each section were counted three times, first using the green channel for the number of eGFP expressing cells, then the red channel for PGP9.5 positive cells, then the blue channel for GFAP positive neurons, and finally the combined channel for multiple-stained structures. The percentage of single- to double-labeled cells in each section was calculated after each section had been counted. Percentages of single- to double-labeled cells were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Real Time RT-PCR

Real time quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess expression of nNOS in rat NTS after transduction with AAV2nNOS. Following extraction with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), RNA of NTS was prepared using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, CA, USA). RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA) with an OD260/OD280 ratio of greater than 1.9. Reverse transcription was performed according to methods described in an earlier publication (Chu et al. 2002) using 300 ng RNA for each sample. We performed real time RT-PCR in 96-well plate with identical amount of reverse transcription product using nNOS TagMan® Expression Assays and eNOS TagMan® Expression Assays purchased from Applied Bio-systems (Carlsbad, CA, USA). These kits contain probes and primers for real time RT-PCR for nNOS and eNOS. RT-PCR for β actin (Rat ACTB Endogenous Control, Applied Bio-systems) was used as an endogenous reference control and was performed in the same well as nNOS or eNOS. FAM fluorphore was used for nNOS or eNOS, VIC® fluorphore was used for β actin. Expression levels of nNOS or eNOS were first normalized by β actin level, and relative expression levels were then obtained using the ΔΔCt method (Wakisaka et al. 2010).

Western Blot Analysis

Procedures like those in our previous publication (Lin and Talman 2005b) were used for Western blot analysis of nNOS. In brief, we homogenized HEK293 cells or NTS tissue in homogenization buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). After centrifugation, protein concentration of the supernate was determined using Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Homogenates containing 10 μg protein were separated alongside Bio-Rad Precision Plus Proteins Standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by 7.5% SDS-polyacrylaminde gel electrophoresis (Ready Gel, Bio-Rad Laboratories) using the Mini Protein II System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to Laemmli (1970). The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using the Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The blot was blocked in 10% milk in PBS and then incubated with sheep anti-nNOS (1:20,000) antibody, described above for fluorescent immunostaining, at 4°C for 24 h. After a thorough wash, the blot was incubated with horseradish peroxide-conjugated anti-sheep antibody (1:10,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab.) at 25°C for 4 h. Protein bands were visualized with ECL Plus™ Western Blotting Reagents (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences, South San Francisco, CA, USA) and exposed to X-ray films.

We used glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAPDH) as an internal control for Western analysis of rat NTS. Goat anti-GAPDH antibody (1:20,000) was purchased from GenSCript (Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Results

AAV2eGFP Injection

AAV2eGFP in NTS

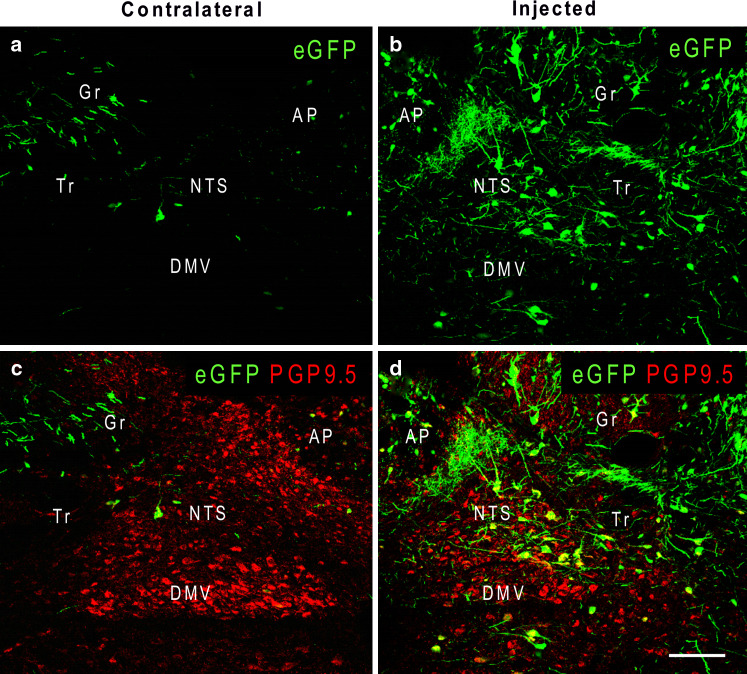

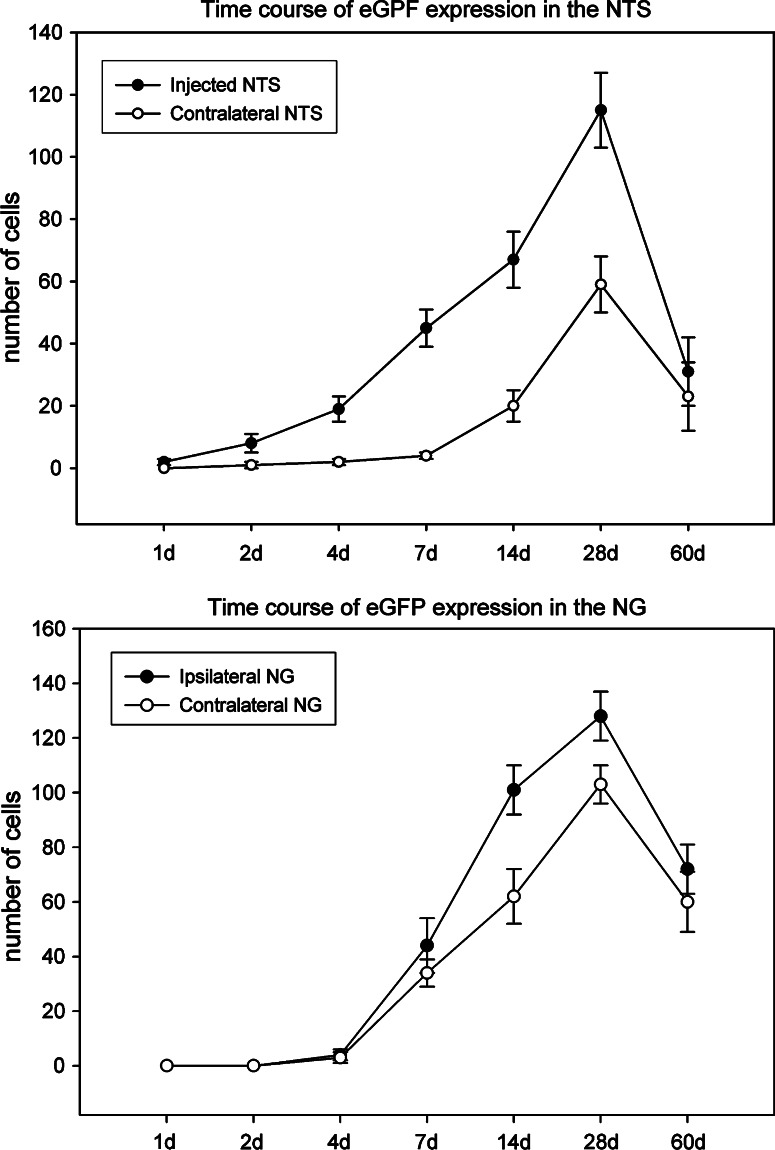

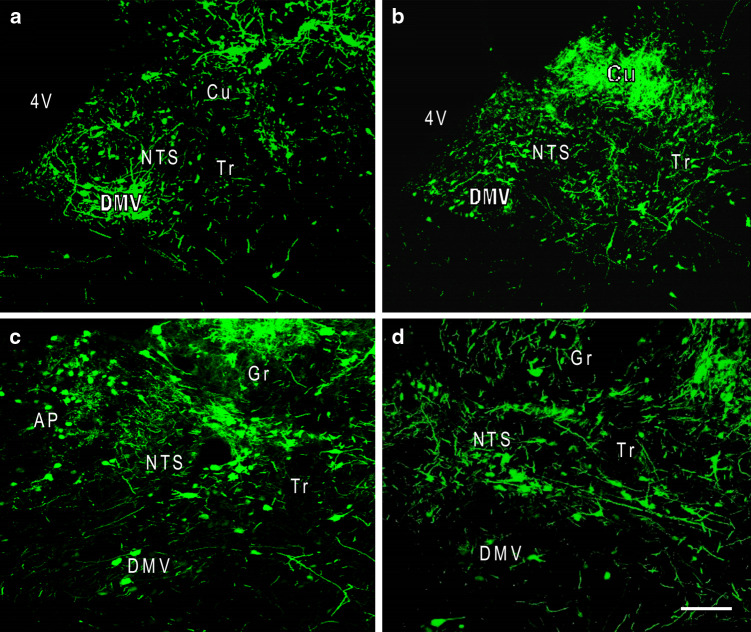

We noted expression of eGFP, the marker protein of AAV2 gene transfer in this study, in the NTS after the vectors had been injected into the area (Fig. 1b, d). We observed one or two eGFP expressing cells in the injected NTS 1 day after AAV2eGFP injection. The number of transfected cells in the NTS increased from day 1 through day 28 after the injection of AAV2eGFP (Fig. 2, top panel). These eGFP expressing cells were seen throughout the rostral-caudal length of the NTS from day 7 (Fig. 3) through day 28. Although we did not analyze it quantitatively, we noted that the intensity of eGFP fluorescence in cell bodies also appeared to increase over time. In addition, the density of eGFP expressing fibers also appeared to increase from day 1 to day 28. On day 28, the density of eGFP expressing fibers in the NTS became so great that it was often hard to clearly identify the boundary of individual cell bodies. On day 60, there was a decrease in the number of eGFP expressing cells in the NTS and their staining intensity (Fig. 2, top panel).

Fig. 1.

Pseudo-colored confocal images of the rat NTS at the injection level 7 days after AAV2eGPF had been injected unilaterally into this nucleus, which then was subjected to immunofluorescent staining for PGP9.5 (c, d) to show the structure of the NTS. Numerous cells and fibers expressing eGFP (green), the fluorescent protein, are observed in the injected side (b, d). Transfected cells in the adjacent areas, such as the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV), area postrema (AP), and gracilus nucleus (Gr) are also noted. A few cells and fibers expressing eGFP are observed in the contralateral NTS (a, c). Panels c and d are merged confocal images of eGFP and PGP9.5-IR of the same section as a and b, respectively. Tr tractus solitarius. Scale bar = 100 μm

Fig. 2.

Time course of eGFP expression in NTS (upper panel) and NG (lower panel) after unilateral injection of AAV2eGFP into the NTS. The number of eGFP expressing cells (average per section) increased from day 1 to day 28, and then decreased on day 60 in both the injected and contralateral NTS. The number of eGFP expressing cells first appeared on day 4, increased until day 28, and then decreased on day 60 in both ipsilateral and contralateral NG

Fig. 3.

Confocal images of rostral-caudal levels of the NTS 7 days after AAV2eGFP had been injected into this nucleus. Neurons and fibers expressing eGFP are seen throughout the length of NTS. a Rostral level at Bregma −12.7 mm, b intermediate level at Bregma −13.3 mm, c subpostremal level at Bregma −13.7 mm, d caudal level at Bregma −14.2 mm. 4V 4th ventricle, Cu cuneate nucleus, DMV dorsal motor neuron of vagus, Gr gracilus nucleus, Tr tractus solitarius. Scale bar = 100 μm

We also observed eGFP expressing cells and fibers in the contralateral NTS. One or two cells that weakly expressed eGFP were noted 2 days after the injection. The expression of eGFP in cells and fibers in the contralateral NTS became more evident on day 7 (Fig. 1a, c). The number of eGFP expressing cells in the contralateral NTS also increased over time from day 2 to day 28. However, the number of eGFP expressing cells in the contralateral NTS was always fewer than in the injected side for the same survival time period (Fig. 2, top panel). Similar to observations in the injected NTS, the intensity of eGFP fluorescence in cell bodies also increased from day 2 to day 28. The density of eGFP expressing fibers in the contralateral NTS also increased from day 2 to day 28. On day 60, there were fewer eGFP expressing cell in the NTS (Fig. 2, top panel) and a lower density of fibers that expressed eGFP.

Some neurons and fibers in adjacent structures, such as the area postrema (AP), dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV), and gracilus nucleus (Gr), also were observed to express eGFP on day 2 and to become more abundant over time (Fig. 1b, d), reaching a maximum by day 28, and then decreasing by day 60.

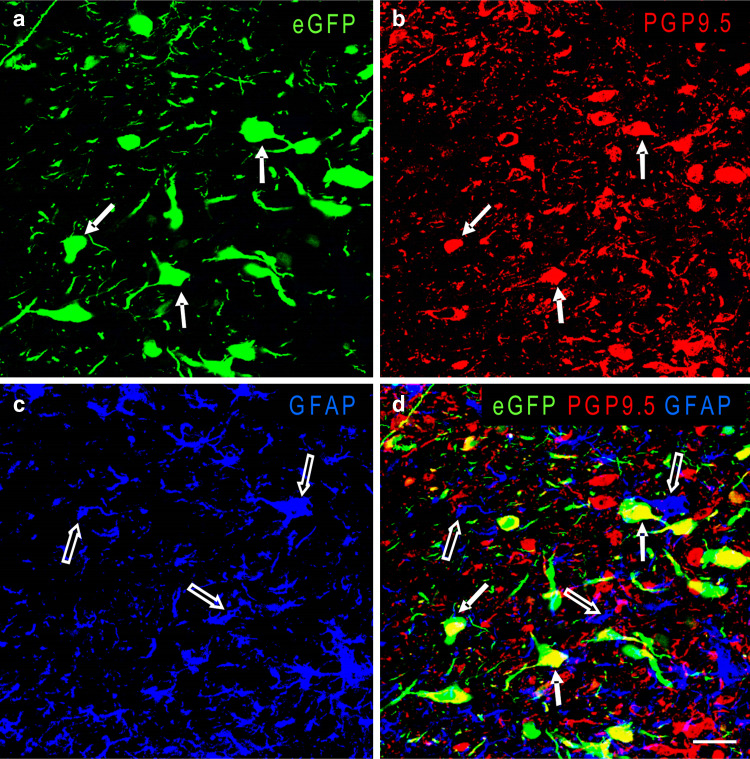

Type of Cells Transduced

Double-label immunofluorescent staining showed that 92.9 ± 7.0% (1,553 cells were counted) of NTS cells expressing eGFP after AAV2eGFP had been injected were positive for PGP9.5-IR but none contained for GFAP-IR (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the majority of eGFP expressing cells in the contralateral NTS were positive for PGP9.5-IR and negative for GFPA-IR.

Fig. 4.

Confocal images of rat NTS 7 days after injection of AAV2eGFP into the nucleus, which was then subjected to double immunofluorescent staining for PGP9.5 and GFAP. Panel d is a merged confocal image of panels a (eGFP, green), b (PGP9.5, red) and c (GFAP, blue). White arrows in a, b and d indicate representative cells that are positive for both eGFP and PGP9.5-IR and thus appear yellow in the merged image in panel d. Note that the majority of AAV2eGFP transduced NTS cells also contain PGP9.5-IR, and none of them contains GFAP-IR. Empty arrows in c and d indicate cells and processes that contain only GFAP-IR. Scale bar = 20 μm

The majority of eGFP expressing cells in the AP, DMV, and Gr, also stained for PGP9.5-IR but not for GFAP-IR. For example, 92.2 ± 4.6% (619 cells were counted) of cells in the DMV were positive for PGP9.5-IR and none was positive for GFAP-IR.

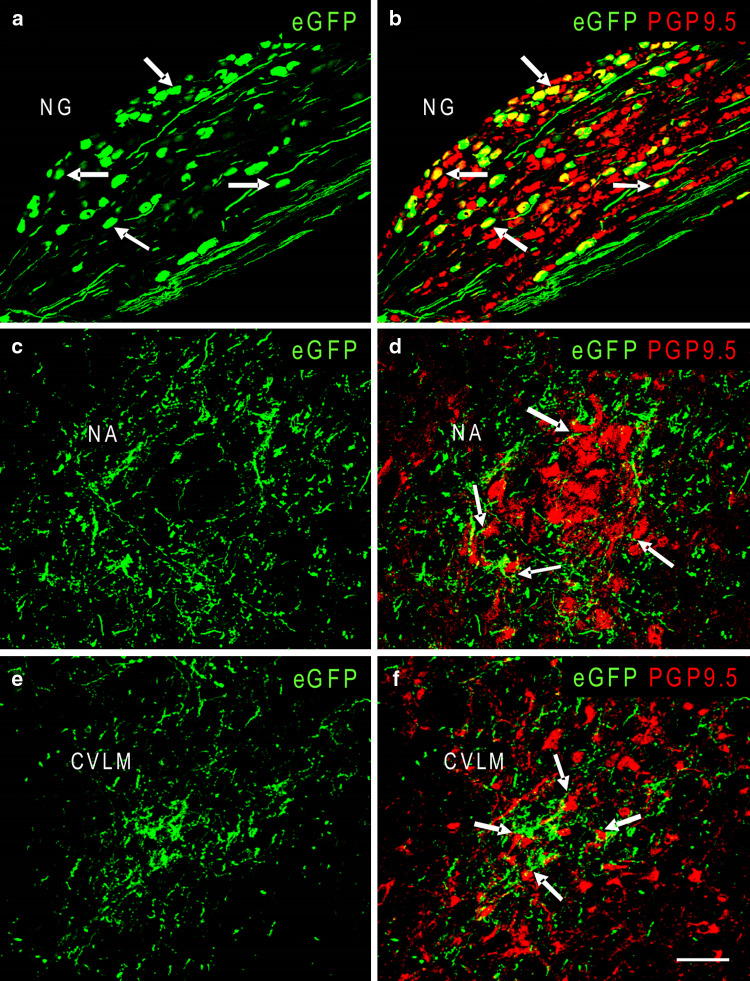

AAV2eGFP in NG

We observed a few eGFP expressing cells and fibers in the ipsilateral and contralateral NG on day 4 after AAV2eGFP had been injected into the NTS. The number of eGFP expressing cells in both the ipsilateral and contralateral NG increased from day 4 to day 28, and decreased on day 60 (Fig. 2, bottom panel). Similar to what was observed in the NTS, the majority (94.6 ± 1.8% of 1,872 cells counted) of cells expressing eGFP also contained PGP9.6-IR (Fig. 5a, b) while none contained GFAP-IR.

Fig. 5.

Confocal images with immunofluorescent stain for PGP9.5 of the ipsilateral NG, NA and CVLM 14 days after unilateral injection of AAV2eGFP into the NTS. Numerous cells and fibers expressing eGFP are seen in the NG, as shown in a. Panel b, a merged confocal image of the same section as panel a, shows both eGFP (green) and PGP9.5-IR (red). Arrows in a and b indicate NG neurons that are double-labeled for eGFP and PGP9.5-IR and appear yellow. Numerous eGFP expressing fibers are noted in the NA (c) and CVLM (e). Panels d and f, merged confocal images of the same sections b and c, respectively, show both eGFP expression and PGP9.5-IR. Fibers expressing eGFP in the NA and CVLM often surround and are in close apposition to cell bodies (arrows in d and f) that do not express eGFP but are positive for PGP9.5-IR. Scale bar = 100 μm in a–b, 50 μm in c–f

AAV2eGFP in NA, CVLM, RVLM, and Other Brain Areas

Fibers expressing eGFP were seen in both the ipsilateral and contralateral NA on day 4 after the injection of AAV2eGFP into the NTS. The density of eGFP expressing fibers also appeared to increase from day 4 to day 28. Some eGFP expressing fibers surrounded NA neurons with close apposition to cell bodies (Fig. 5c, d) of these neurons on day 14, day 28, and day 60. NA neuronal cell bodies rarely contained eGFP; however, we observed occasional low intensity eGFP fluorescence in some NA neurons on day 14, day 28, and day 60. In addition to the NA, we also noted eGFP expressing fibers in the both the ipsilateral and contralateral CVLM and RVLM on day 7 after injection. The density of eGFP expressing fiber also appeared to increase from day 7 to day 28 and decreased on day 60. Some eGFP expressing fibers were seen surrounding neurons in the CVLM (Fig. 5) and RVLM and were sometimes in close apposition to cell bodies of these neurons on day 14, day 28, and day 60. However, we did not see eGFP expressing neurons in either CVLM or RVLM at any time.

We also observed eGFP expressing fibers in other brain regions where NTS projects. For example, eGFP expressing fibers were present in the ipsilateral and contralateral parabrachial nucleus, lateral hypothalamus, paraventricular nucleus, substantia nigra, midbrain periaqueductal gray, and dorsomedial thalamus on day 14 after injection and persisted on day 60. We did not see eGFP expressing neurons in any of these areas at any time.

AAV2nNOS Injection

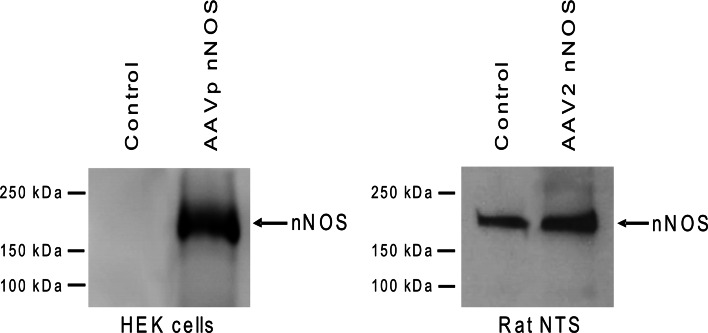

As a first step, we used HEK cells to test if AAV2 plasmid that carries nNOS cDNA can induce HEK cells to express nNOS. Figure 6 shows that HEK cells (left panel) expressed high level of nNOS protein after they were incubated with AAVp-nNOS. In contrast, un-treated HEK cells did not express nNOS (Fig. 6). Having established that AAVp-nNOS induced nNOS expression in cell culture, we then prepared AAV2nNOS and injected the vector into rat NTS to determine if nNOS expression in the NTS is up-regulated. Results from real time RT-PCR demonstrated that 2 weeks after introduction of AAV2nNOS, mRNA levels in the NTS of the injected rats increased 11.4 ± 2.3 fold (P < 0.005), when compared to that in un-injected control rats (Fig. 7, left panel). As an additional control, we demonstrated that mRNA levels of eNOS were not altered (Fig. 7, right panel).

Fig. 6.

Representative Western blots showing increased expression of nNOS protein in HEK cells (left panel) and rat NTS (right panel) after transduction with AAVp-nNOS plasmid or AAV2nNOS, respectively. HEK cells that were not treated with AAVp-nNOS and rat NTS that were not injected with AAV2nNOS served as control. There was no change in GAPDH expression in rat NTS after transduction (not shown). All lanes were loaded with 10 μg of protein. Positions of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left side of each panel

Fig. 7.

Real time RT-PCR results showing injection of AAV2nNOS significantly (left panel, **P < 0.005) increased mRNA levels of nNOS in the NTS of rats (n = 5), as compared with that of un-injected control rats (n = 4) NTS. Data were normalized by β actin expression. Analyses of the same group of rats showed that levels of eNOS mRNA were not changed (right panel). Values were the average of 2 sets of real time RT-PCR, with nearly identical results for each NTS sample

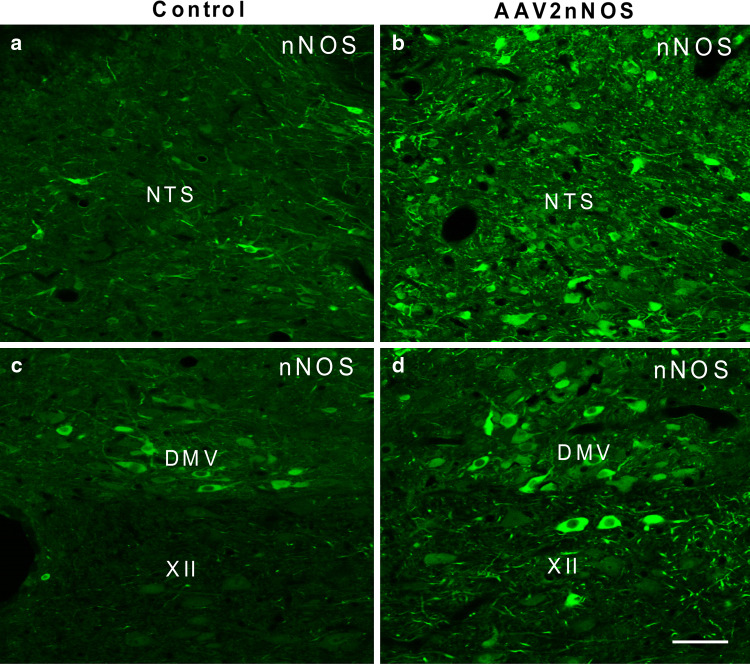

Western blot analysis demonstrated increased expression of nNOS protein after injection of AAV2nNOS into the NTS (Right panel of Fig. 6) when compared to that in un-injected control rats. Such increased nNOS protein in NTS was consistent with results from immunofluorescent staining of nNOS (Fig. 8), which showed increased nNOS-IR in both fibers and cell bodies of NTS neurons. The DMV, which is adjacent to the NTS, also appeared to have increased nNOS-IR (Fig. 8), and some hypoglossal cells, which normally do not express nNOS, expressed nNOS-IR after transduction (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Confocal images showing increased nNOS-IR in the NTS after AAV2nNOS injection into the area (panel b) as compared with that in the un-injected control rat (a). This increase was also observed in adjacent areas such as the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV) and hypoglossal nucleus (XII) in AAV2nNOS injected rats (panel d) as compared with that of the control rat (c). Scale bar = 50 μm

Discussion

This study makes the following four contributions. (1) It demonstrates that AAV2eGFP microinjected into the rat NTS transduces cells to express eGFP. This transduction reached its peak on day 28 and lasted for at least 60 days. (2) It demonstrates that the majority of transduced NTS cells were neurons, as indicated by their containing IR of the neuronal marker, PGP9.5. (3) It demonstrates that AAV2 vectors were retrogradely transported from the NTS to the NG and anterogradely transported from the NTS to the NA, CVLM, and RVLM. There was no evidence of trans-synaptic transport of the vector at those sites. (4) It demonstrates that AAV2 vectors containing nNOS cDNA increased mRNA and protein levels of nNOS in the NTS.

Our observation that AAV2 vectors were capable of transducing non-mitotic neurons in the NTS is consistent with that of other studies in other areas of the brain (Gasmi et al. 2007; Belur et al. 2008). Among different serotypes of AAV vectors, AAV2 is the most widely used in neurological gene therapy in humans, largely because of its ability to transduce neural cells in rodent and primate brain (Nomoto et al. 2003; Palomeque et al. 2007; Markakis et al. 2010). The mechanism for AAV2’s tropism for neurons most likely involves the unique structure of its capsids, which may bind to specific membrane-associated receptors in neurons (Michelfelder and Trepel 2009; Mason et al. 2010). This selectivity makes AAV2 an excellent vector for gene transduction in NTS neurons when studies are aimed at proteins that are typically found in neurons. For example, AAV2 would target the source of the endogenous enzyme when one seeks to study the role of nNOS within the NTS where the enzyme is found exclusively in neurons (Lin and Talman 2005a; Lin et al. 2007). AAV2 is, then, one of a group of good viral vectors for this purpose. For example, neuronal tropism is also achieved with the feline immunodeficiency virus vector in the rat NTS (Lin et al. 2010).

Another advantage of AAV2 as a gene transfer tool is that its transduction is long-lasting. Our results show that AAV2eGFP expression in the NTS lasted for at least 2 months, the longest time point in our study. Previous studies in CNS and PNS have demonstrated that gene transduction of AAV2 usually lasts for more than 6 months and may persist for more than a year (Gasmi et al. 2007; Belur et al. 2008; Hadaczek et al. 2010). In contrast, adenovirus gene expression may diminish 1 month after injection (Boulis et al. 1999) and lentivirus gene expression may be limited to 3 months (Naldini et al. 1996). The reason that gene expression of AAV vectors lasts longer has been attributed to there being no viral coding sequence in the AAV vector DNA. There is, therefore, no expression of viral protein to induce an immune reaction by the host (McCown 2005). Though chronic transduction is a valuable feature of AAV, it has been suggested that chronicity may vary in different brain regions (McCown et al. 1996). Furthermore, the choice of promotor may significantly influence both pattern and longevity of gene expression in the CNS because diminution in gene expression may result from promotor suppression rather than loss of transduced cells (Klein et al. 1998; McCown 2005). Our AAV2eGFP vector contained a CMV promotor, which is one of the strongest constitutively active virus-derived transcription elements (Nomoto et al. 2003). Longer-lasting gene expression may be achieved by using an endogenous promotor, such as neuron specific enolase, as suggested by some investigators (Klein et al. 1998). Compared to adenovirus vectors, which are highly efficient (although transient) and provide high level of expression of transgene (Sinnayah et al. 2002; Lonergan et al. 2005), AAV2 vectors sometimes do not offer high levels of expression of transgene in tissues other than brain and muscle (Sanlioglu et al. 2001; Zhong et al. 2008). This problem has been attributed to the rate-limiting steps of AAV transduction, in which the single-stranded AAV viral DNA failed to be converted to the transcriptionally active double-stranded form efficiently (Sanlioglu et al. 2001; Zhong et al. 2008). Furthermore, high levels of adenovirus transduction are often observed within 1 week, high levels of AAV transduction are not noted until 2–3 weeks after introduction of the vectors.

After AAV2eGFP was injected into the NTS, we observed numerous eGFP expressing neurons and fibers in the NG both ipsilateral and contralateral to the injection. This observation indicates that AAV2eGPF was taken up by terminals in the NTS and retrogradely transported to the NG. The observation that AAV2 vectors are capable of undergoing retrograde transport in the nervous system has been reported in several studies (Kaspar et al. 2002; Johnston et al. 2009). In contrast, some investigators did not observe retrograde transport of AA2 even when they studied similar areas of the brain (Chamberlin et al. 1998; Burger et al. 2004; Hollis et al. 2008). The reason for the discrepancy between these studies is not clear (Burger et al. 2004; Hollis et al. 2008). Of note, AAV2 is not the only AAV serotype that can be retrogradely transported. Serotypes AAV1 and AAV5 may similarly undergo retrograde transport in the nervous system (Burger et al. 2004; Hollis et al. 2008).

We also observed anterograde transport of AAV2eGFP (or eGFP protein) from the NTS to the NA, CVLM, and RVLM. This finding was consistent with a report that showed anterograde transport of AAV2 vector when it was injected into the putamen of Rhesus monkey (Johnston et al. 2009). Again anterograde transport is not a unique property of AAV2 but may also occur with AAV1 and AAV9 (Cearley and Wolfe 2007). Indeed, it has been suggested that AAV vectors may be used as tract tracers that may even be superior to biotinylated dextran amines and Phaseolus vulgaris leukoagglutinin because AAV vectors produce a clearly defined injection site and are not taken up by all type of cells (Chamberlin et al. 1998). Since AAV vectors can be transported long distances and may last for a long time, it has been considered a particularly good anterograde tracer for long axonal pathways (Chamberlin et al. 1998). Our finding some neurons that express eGFP in the NA is most likely due to the suggested bidirectional connection between the NTS and some neurons of the NA (Hayakawa et al. 1997) and not because AAV2 was transported trans-synaptically. Other than the NA, we observed only eGFP expressing fibers, and not neurons, at other sites that receive projections from NTS. Therefore, it is not likely that AAV2 underwent trans-synaptic transport from the NTS to the NA. Supporting this suggestion, we found no reports that indicate AAV2 may undergo trans-synaptic transport. On the other hand, one study suggests that AAV1 and AAV9 may be transported anterogradely, released and taken up by target cells (Cearley and Wolfe 2007).

Since AAV vector may transduce neurons and is capable of retrograde axonal transport, AAV2 may be a vector of choice when seeking to deliver gene to specific neurons that are not easily directly approachable. For example, injection of AAV2 vectors into muscle or peripheral nerve to allow retrograde transport to motor neurons of spinal cord may provide a noninvasive approach for treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Kaspar et al. 2002). In the NTS, AAV2 vector may be useful also as a retrograde tracer and an anterograde tracer, by itself or combined with other methods, to study areas that project to this nucleus. In contrast to AAV2, feline immunodeficiency virus vector, which does not undergo any type of transport could be the vector of choice when targeting neurons at the site of delivery (Lin et al. 2010). In the latter case, physiological changes as a result of the vector introduction could be more reliably attributed to effects on those local neurons.

Finally, and most importantly, we demonstrated that AAV2 vectors were capable of carrying nNOS cDNA and up-regulating it in the rat NTS by real time RT-PCR, Western blot analysis and immunofluorescent staining. Our studies were done 2 weeks after the injection of AAV2nNOS vectors. Based on our studies of AAV2eGFP, higher levels of up-regulation would be expected at 3 weeks. The elevated levels of nNOS found with RT-PCR and Western blot analysis were most likely produced from NTS neurons, the target of the vector. AAV2nNOS vector thus can be used as a specific gene transfer tool to delineate the role of nNOS in CNS neurons without the complication of transfecting glial cells or other type of cells. However, interpretation of results from such studies should take into consideration that this vector may undergo anterograde and retrograde transport.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yi Chu for his help with quantitative real time RT-PCR. This work was funded in part by NIH RO1 HL 59593 (to W. T. Talman) and NIH RO1 HL 088090 (to L. H. Lin and W. T. Talman).

Abbreviations

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- AAV2

Adeno-associated virus type 2

- AAV2eGFP

Adeno-associated virus type 2 encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein

- AAV2nNOS

Adeno-associated virus type 2 encoding cDNA of nNOS

- AP

Area postrema

- CMV promotor

Cytomegalovirus promotor

- CVLM

Caudal ventrolateral medulla

- DMV

Dorsal motor nucleus of vagus

- eGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

- Gr

Gracilus nucleus

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- NA

Nucleus ambiguus

- NG

Nodose ganglion

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RVLM

Rostral ventrolateral medulla

- PGP9.5

Protein gene product 9.5

- NTS

Nucleus tractus solitarii

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- RRX

Rhodamine red X

- Tr

Tractus solitarius

References

- Allen AM, Dosanjh JK, Erac M, Dassanayake S, Hannan RD, Thomas WG (2006) Expression of constitutively active angiotensin receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla increases blood pressure. Hypertension 47:1054–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belur LR, Kaemmerer WF, McIvor RS, Low WC (2008) Adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors: transduction and long-term expression in cerebellar Purkinje cells in vivo is mediated by the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1: bFGFR-1 mediates AAV2 transduction of Purkinje cells. Arch Virol 153:2107–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscan P, Pickering AE, Paton JF (2002) The nucleus of the solitary tract: an integrating station for nociceptive and cardiorespiratory afferents. Exp Physiol 87:259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulis NM, Turner DE, Dice JA, Bhatia V, Feldman EL (1999) Characterization of adenoviral gene expression in spinal cord after remote vector delivery. Neurosurgery 45:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RM, King MS, Wang L, Shu X (1996) Neurotransmitter and neuromodulator activity in the gustatory zone of the nucleus tractus solitarius. Chem Senses 21:377–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Glatt CE, Lowenstein C, Reed RR, Snyder SH (1991) Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P-450 reductase. Nature 351:714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard DL, Altschuler SM (2000) Brainstem viscerotopic organization of afferents and efferents involved in the control of swallowing. Am J Med 108(Suppl 4a):79S–86S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueler H (1999) Adeno-associated viral vectors for gene transfer and gene therapy. Biol Chem 380:613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Gorbatyuk OS, Velardo MJ, Peden CS, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, Reier PJ, Mandel RJ, Muzyczka N (2004) Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther 10:302–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley CN, Wolfe JH (2007) A single injection of an adeno-associated virus vector into nuclei with divergent connections results in widespread vector distribution in the brain and global correction of a neurogenetic disease. J Neurosci 27:9928–9940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Du B, de Lacalle S, Saper CB (1998) Recombinant adeno-associated virus vector: use for transgene expression and anterograde tract tracing in the CNS. Brain Res 793:169–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen H, Hoffmann A, Cool DR, Diz DI, Chappell MC, Chen AF, Morris M (2006) Adenovirus-mediated small-interference RNA for in vivo silencing of angiotensin AT1a receptors in mouse brain. Hypertension 47:230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Heistad DD, Knudtson KL, Lamping KG, Faraci FM (2002) Quantification of mRNA for endothelial NO synthase in mouse blood vessels by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22:611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RAL (1994) Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev 74:323–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham HD, Lochmuller H, Jani A, Acsadi G, Massie B, Karpati G (1996) Toxicity of replication-defective adenoviral recombinants in dissociated cultures of nervous tissue. Exp Neurol 140:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasmi M, Brandon EP, Herzog CD, Wilson A, Bishop KM, Hofer EK, Cunningham JJ, Printz MA, Kordower JH, Bartus RT (2007) AAV2-mediated delivery of human neurturin to the rat nigrostriatal system: long-term efficacy and tolerability of CERE-120 for Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 27:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaczek P, Eberling JL, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS (2010) Eight years of clinical improvement in MPTP-lesioned primates after gene therapy with AAV2-hAADC. Mol Ther 18:1458–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Zheng JQ, Yajima Y (1997) Direct synaptic projections to esophageal motoneurons in the nucleus ambiguus from the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Comp Neurol 381:18–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Leichner TM, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Bence KK, Grill HJ (2010) Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab 11:77–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Simonian SX, Norris PJ, Emson PC (1996) Relationship of neuronal nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity to GnRH neurons in the ovariectomized and intact female rat. J Endocrinol 8:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Sakai K, Kishi T, Ito K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A (2003) Enhanced depressor response to endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene transfer into the nucleus tractus solitarii of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res 26:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis ER, Kadoya K, Hirsch M, Samulski RJ, Tuszynski MH (2008) Efficient retrograde neuronal transduction utilizing self-complementary AAV1. Mol Ther 16:296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LC, Eberling J, Pivirotto P, Hadaczek P, Federoff HJ, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS (2009) Clinically relevant effects of convection-enhanced delivery of AAV2-GDNF on the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway in aged rhesus monkeys. Hum Gene Ther 20:497–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Sullivan JM (1982) Brainstem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus nerve in the rat. J Comp Neurol 211:248–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt MG, Xiao X, Samulski RJ, Li J, Ojamaa K, Klein IL, Makimura H, Kaplitt MJ, Strumpf RK, Diethrich EB (1996) Long-term gene transfer in porcine myocardium after coronary infusion of an adeno-associated virus vector. Ann Thorac Surg 62:1669–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar BK, Erickson D, Schaffer D, Hinh L, Gage FH, Peterson DA (2002) Targeted retrograde gene delivery for neuronal protection. Mol Ther 5:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Meyer EM, Peel AL, Zolotukhin S, Meyers C, Muzyczka N, King MA (1998) Neuron-specific transduction in the rat septohippocampal or nigrostriatal pathway by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Exp Neurol 150:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural protein during the assemble of the head of bacterophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Jarrott B (1996) Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Prog Neurobiol 48:21–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH (2009) Glutamatergic neurons say NO in the nucleus tractus solitarii. J Chem Neuroanat 38:154–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT (2005a) Nitroxidergic neurons in rat nucleus tractus solitarii express vesicular glutamate transporter 3. J Chem Neuroanat 29:179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT (2005b) Soluble guanylate cyclase and neuronal nitric oxide synthase colocalize in rat nucleus tractus solitarii. J Chem Neuroanat 29:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT (2006) Vesicular glutamate transporters and neuronal nitric oxide synthase colocalize in aortic depressor afferent neurons. J Chem Neuroanat 32:54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Cassell MD, Sandra A, Talman WT (1998) Direct evidence for nitric oxide synthase in vagal afferents to the nucleus tractus solitarii. Neuroscience 84:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Edwards RH, Fremeau RT, Fujiyama F, Kaneda K, Talman WT (2004) Localization of vesicular glutamate transporters colocalizes with and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Neuroscience 123:247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Taktakishvili O, Talman WT (2007) Identification and localization of cell types that express endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Brain Res 1171:42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Langasek JE, Talman LS, Taktakishvili OM, Talman WT (2010) Feline immunodeficiency virus as a gene transfer vector in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30:339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan T, Teschemacher AG, Hwang DY, Kim KS, Pickering AE, Kasparov S (2005) Targeting brain stem centers of cardiovascular control using adenoviral vectors: impact of promoters on transgene expression. Physiol Genomics 20:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markakis EA, Vives KP, Bober J, Leichtle S, Leranth C, Beecham J, Elsworth JD, Roth RH, Samulski RJ, Redmond DE Jr (2010) Comparative transduction efficiency of AAV vector serotypes 1–6 in the substantia nigra and striatum of the primate brain. Mol Ther 18:588–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MR, Ehlert EM, Eggers R, Pool CW, Hermening S, Huseinovic A, Timmermans E, Blits B, Verhaagen J (2010) Comparison of AAV serotypes for gene delivery to dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Ther 18:715–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown TJ (2005) Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in the CNS. Curr Gene Ther 5:333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown TJ, Xiao X, Li J, Breese GR, Samulski RJ (1996) Differential and persistent expression patterns of CNS gene transfer by an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. Brain Res 713:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelfelder S, Trepel M (2009) Adeno-associated viral vectors and their redirection to cell-type specific receptors. Adv Genet 67:29–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage FH, Trono D, Verma IM (1996) Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:11382–11388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie E (1999) CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol 59:299–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto T, Okada T, Shimazaki K, Mizukami H, Matsushita T, Hanazono Y, Kume A, Katsura K, Katayama Y, Ozawa K (2003) Distinct patterns of gene transfer to gerbil hippocampus with recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 and 5. Neurosci Lett 340:153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomeque J, Chemaly ER, Colosi P, Wellman JA, Zhou S, Del Monte F, Hajjar RJ (2007) Efficiency of eight different AAV serotypes in transducing rat myocardium in vivo. Gene Ther 14:989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Hirooka Y, Matsuo I, Eshima K, Shigematsu H, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A (2000) Overexpression of eNOS in NTS causes hypotension and bradycardia in vivo. Hypertension 36:1023–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanlioglu S, Monick MM, Luleci G, Hunninghake GW, Engelhardt JF (2001) Rate limiting steps of AAV transduction and implications for human gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther 1:137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnayah P, Lindley TE, Staber PD, Cassell MD, Davidson BL, Davisson RL (2002) Selective gene transfer to key cardiovascular regions of the brain: comparison of two viral vector systems. Hypertension 39:603–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyer KM, Donoghue S, Felder RB, Jordan D (1984) Processing of afferent inputs in cardiovascular control. Clin Exp Hypertens A A6:173–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT (1989) Kynurenic acid microinjected into the nucleus tractus solitarius of rat blocks the arterial baroreflex but not responses to glutamate. Neurosci Lett 102:247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urabe M, Ding C, Kotin RM (2002) Insect cells as a factory to produce adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors. Hum Gene Ther 13:1935–1943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet KM, Blouin V, Brument N, Agbandje-McKenna M, Snyder RO (2008) The role of the adeno-associated virus capsid in gene transfer. Methods Mol Biol 437:51–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakisaka Y, Chu Y, Miller JD, Rosenberg GA, Heistad DD (2010) Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage during acute and chronic hypertension in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:56–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ (1996) Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol 70:8098–8108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X, Li J, McCown TJ, Samulski RJ (1997a) Gene transfer by adeno-associated virus vectors into the central nervous system. Exp Neurol 144:113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X, McCown TJ, Li J, Breese GR, Morrow AL, Samulski RJ (1997b) Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector antisense gene transfer in vivo decreases GABA(A) alpha1 containing receptors and increases inferior collicular seizure sensitivity. Brain Res 756:76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Su Q, Wilson JM (1996) Role of viral antigens in destructive cellular immune responses to adenovirus vector-transduced cells in mouse lungs. J Virol 70:7209–7212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Scott KA, Hyun J, Tamashiro KL, Tray N, Moran TH, Bi S (2009) Role of dorsomedial hypothalamic neuropeptide Y in modulating food intake and energy balance. J Neurosci 29:179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Zhou X, Li Y, Qing K, Xiao X, Samulski RJ, Srivastava A (2008) Single-polarity recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 vector-mediated transgene expression in vitro and in vivo: mechanism of transduction. Mol Ther 16:290–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]