Abstract

Adenosine receptors are plasma membrane proteins that transduce an extracellular signal into the interior of the cell. Basically every mammalian cell expresses at least one of the four adenosine receptor subtypes. Recent insight in signal transduction cascades teaches us that the current classification of receptor ligands into agonists, antagonists, and inverse agonists relies very much on the experimental setup that was used. Upon activation of the receptors by the ubiquitous endogenous ligand adenosine they engage classical G protein-mediated pathways, resulting in production of second messengers and activation of kinases. Besides this well-described G protein-mediated signaling pathway, adenosine receptors activate scaffold proteins such as β-arrestins. Using innovative and sensitive experimental tools, it has been possible to detect ligands that preferentially stimulate the β-arrestin pathway over the G protein-mediated signal transduction route, or vice versa. This phenomenon is referred to as functional selectivity or biased signaling and implies that an antagonist for one pathway may be a full agonist for the other signaling route. Functional selectivity makes it necessary to redefine the functional properties of currently used adenosine receptor ligands and opens possibilities for new and more selective ligands. This review focuses on the current knowledge of functionally selective adenosine receptor ligands and on G protein-independent signaling of adenosine receptors through scaffold proteins.

Keywords: Adenosine, Receptor, Functional selectivity, Biased signaling, Arrestin, Scaffold protein

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the most important class of drug-targetable cell surface proteins [1]. These receptors couple to several classes of heterotrimeric G proteins consisting of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits that are activated upon receptor stimulation. Subsequently, the heterotrimeric G protein dissociates into Gα and Gβγ subunits, which on their turn activate intracellular targets. There are at least four families of G proteins namely Gαi, Gαs, Gαq, and Gα12/13 that accommodate a variety of combinations between the 16 different Gα, 5 Gβ, and 14 Gγ subunits [2]. Gαs and Gαi proteins activate or inactivate adenylate cyclase (AC), respectively, resulting in an increase or reduction of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) concentrations. Gαq proteins activate phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms, resulting in for instance formation of inositol phosphates and a raise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Activation of Gα12/13 proteins is associated with changes of the cytoskeleton. The Gβγ subunits activate a broad variety of signal transduction pathways upon their release, such as PLC, AC, protein kinase D, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and ion channels [2].

GPCRs consist of seven membrane-spanning α-helices and are more and more often referred to as seven transmembrane receptors (7TMRs). This is not merely because of their membrane topology, but to account for the observation that these receptors can activate a variety of other proteins besides G proteins. The best studied G protein-independent signal transduction pathway activated by 7TMRs is the one mediated by β-arrestins. Upon activation, 7TMRs are phosphorylated at their intracellular domains by GPCR kinases (GRKs), followed by recruitment and binding of β-arrestin-1 (also named arrestin-2), β-arrestin-2 (also named arrestin-3), or the visual arrestins-1 and −4 [3–5].

Binding of β-arrestin functions as an off-switch for the receptor by preventing interaction with G proteins and mediates internalization of the receptor. Besides their role in receptor desensitization and internalization, β-arrestins can function as adapter or scaffold proteins that mediate G protein-independent activation of, e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), Src, JNK, PI3K, or the transcription factor NF-κB [6, 7].The MAPKs ERK1/2 are two signaling proteins where G protein-dependent and β-arrestin-mediated pathways can converge. Activation of ERK1/2 by 7TMRs occurs via a variety of pathways and is often dependent on the cellular background in which such a response is measured. G protein-dependent ERK1/2 activation is spatially and temporally distinct from β-arrestin-mediated G protein-independent phosphorylation [6, 8]. ERK1/2 activation via G proteins often is rapid and transient, while β-arrestin-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation is delayed and sustained. Furthermore, ERK1/2 activated by β-arrestins has been reported to remain cytosolic, while ERK1/2 activated through G proteins is localized in the nucleus in addition to the cytosol [8].

7TMRs can be divided in two classes dependent on their interaction with β-arrestins: The first class binds β-arrestin-2 with higher affinity than β-arrestin-1, while the second class of receptors binds both β-arrestins with equal affinity and additionally binds visual arrestins [4]. While β-arrestin-1 and visual arrestin are found in both the cytoplasm and nucleus in the absence of an agonist in transfected human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells, localization of β-arrestin-2 is restricted to the cytoplasm [4]. Specific serine residues in the C-terminal tails of 7TMRs were shown to determine specificity for either β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2. The complexes of receptors of the first class with β-arrestins were described to be relatively unstable and to readily dissociate at or near the plasma membrane, while β-arrestins bound to receptors of the second class were found to be more stable and to internalize together into endocytic vesicles [4]. In addition, β-arrestin-1 and -2 were found to play different roles in internalization but not desensitization or downregulation of 7TMRs [5].

It is likely that β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 fulfill distinct and non-redundant functions in the cell, based on these differences and their different tissue expression. On the other hand, mouse knockout models of either β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 show no gross phenotypes [3], while double knockout mice die at birth [9]. This indicates that absence of a β-arrestin isoform can be compensated for by the other isoform, pointing to at least a certain level of redundancy between the two proteins. Current knowledge from mouse knockout models suggests that β-arrestin-2 plays a more important role in G protein-independent signaling than β-arrestin-1 [3].

Functional selectivity

Many 7TMRs show promiscuous coupling to G proteins. When a receptor activates more than one class of G proteins, distinct conformations of the receptor may favor coupling of one class of G proteins over another. Similarly, when a 7TMR activates a G protein-independent β-arrestin-mediated pathway in addition to G proteins, one pathway may be preferred over the other, depending on the conformational state of the receptor. Moreover, ligands that bind the receptor may induce or stabilize receptor conformations that selectively couple to a certain pathway, while leaving the other pathway unaffected. These events are called functional selectivity or biased signaling. The principles of functional selectivity have been the subject of excellent and extensive reviews [10, 11].

Functional selectivity also implies that the concept of ligand efficacy is very assay dependent, since a full agonist for a certain pathway may be an antagonist, partial agonist or inverse agonist for another pathway mediated by the same receptor. Partial agonism and functional selectivity are two separate phenomena that can produce overlapping responses. It should therefore always be verified that apparent functional selectivity between agonists is not merely caused by variation in efficacy, since a high-efficacy agonist may activate more Gα subtypes than a low-efficacy agonist. For example, a full agonist for a given receptor may activate both Gαi and Gαq proteins, while a partial agonist may activate the Gαi pathway but may not be potent enough to activate Gαq proteins as well. In this case, the partial agonist appears to selectively activate the Gαi pathway, but this originates from a general lack of efficacy at the receptor. Also differences in receptor density between tissues may cause changes in potency and efficacy of agonists. In a tissue expressing high amounts of receptors, a partial agonist can become a full agonist, a mechanism referred to as receptor reserve or spare receptors. Likewise, if the ligand acts as a partial agonist on the tissue with high expression levels of the receptor, it may not be potent enough to elicit a response in a tissue expressing less receptors. However, if agonist A is a full agonist at Gαi and a partial agonist at Gαq, and agonist B reversely shows partial agonism at Gαi and full agonism for the Gαq-mediated pathway, a truly biased signal is observed. Therefore, functional selectivity between agonists is only detected if the rank order of efficacy or potency of the agonists for two pathways is reversed.

The binding site of the natural ligand of a receptor is referred to as the orthosteric binding site. Many receptors are also capable of binding (synthetic) molecules or proteins at sites different from the orthosteric site. These sites are called allosteric binding sites, and the ligands are named allosteric ligands. Allosteric ligands may be agonists on their own right, or modulate the signaling of the orthosteric ligand, in which case they are called positive or negative allosteric modulators, PAMs and NAMs, respectively (for reviews on allosteric modulation of 7TMRs in general see references [11, 12] and for allosteric modulation of adenosine receptors in particular see references [13, 14]). Allosteric ligands induce or stabilize specific receptor conformations, thereby changing the active state of the receptor and/or the mode the orthosteric ligand interacts with the receptor. This can be seen as fine-tuning of the receptor and its response. Even binding of a G protein or other protein to the intracellular domains of a 7TMR can be seen as allosteric modulation, since this interaction stabilizes a certain (active) state of the receptor and influences binding of the orthosteric ligand. Since both orthosteric and allosteric ligands induce specific receptor conformations, interplay between both can be envisioned, so that an allosteric modulator can induce or enhance functional selectivity of an orthosteric ligand.

From a drug development point of view, the possibility to activate one pathway while leaving other pathways untouched offers unique possibilities with respect to selectivity and the prevention of side effects. For instance, the use of nicotinic acid to lower triglycerides and raise high-density lipoproteins is hampered by the adverse effects of cutaneous flushing, burning, and itching, since all these effects are mediated by the hydroxy-carboxylic acid receptor HCA2 (also named GPR109A). It seems however that cutaneous flushing is mediated by a β-arrestin-dependent pathway, while the anti-lipolytic effect is not [15]. Interestingly, a synthetic compound called MK-0354 lacks the vasodilatory effects responsible for skin flushing, but retains the anti-lipolytic signaling in vivo [16]. Indeed, MK-0354 was found to activate G protein-dependent pathways, but not β-arrestin signaling [15, 16], indicating that it is possible to separate desired and unwanted effects using functionally selective drugs. This is only one example out of many: several other receptors for which a bias between G protein-dependent and β-arrestin signaling pathways has been described, such as the β1-and β2-adrenergic receptors, the μ-opioid receptor, the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R), serotonin receptors 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C, the angiotensin AT1A receptor, the chemokine CXCR4 receptor and the parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor have been recently reviewed [6].

Members of the JNK MAPK family have been shown to be important mediators of biased signaling events at opioid receptors [17]. It has been known for some time that a class of μ-opioid ligands, including morphine, does not induce robust phosphorylation and internalization of the receptor, in contrast to other ligands such as endogenous enkephalins. Ligand-directed JNK activation was found to block G protein-coupling to κ-and μ-opioid receptors and to be involved in long-term inactivation of the κ-opioid receptor as well as acute analgesic tolerance of the μ-opioid receptor [17]. The mechanism leading to ligand-directed JNK activation is presently unknown but may involve β-arrestins. Nevertheless, JNK could represent a novel mediator of functionally selective responses for GPCRs in general.

Most research regarding functional selectivity has focused on selective activation of different classes of G proteins, or biased activation of β-arrestins versus G proteins. However, besides β-arrestins, 7TMRs interact with a variety of other intracellular scaffold proteins. Scaffold proteins can link the 7TMR to one or more other effectors, thereby facilitating efficient signal transduction by bringing all partners together in the same signaling complex. Scaffold proteins for instance can physically interact with proteins such as ERK1/2, Src, JNK, PLC, protein kinase A (PKA), ADP-ribosylation factor-nucleotide site opener (ARNO) and actin (see reference [7] for a review). Src, which is important in several signaling cascades leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation, has even been shown to be directly activated by the β2-adrenergic receptor [18]. Theoretically, scaffold proteins can stabilize receptor conformations that lead to functional selectivity. In practice, however, it will often be difficult to experimentally separate scaffolding functions from the allosteric effects induced by scaffold proteins [7].

Many scaffold proteins contain one or more PDZ (postsynaptic density protein 95/Discs-large/Zo-1 protein) motifs that interact with the distal part of the carboxyl terminus of 7TMRs. While phosphorylation of 7TMRs by GRKs often leads to recruitment of β-arrestins, phoshorylation of serine or threonine residues in a PDZ domain can prevent the association of a receptor with a scaffold protein [7]. Phosphorylation of 7TMRs by specific GRKs appears to be crucial for some biased responses, such as those elicited by the endogenously expressed chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 upon binding to the chemokine receptor CCR7. Although both ligands have comparable binding affinities and activate G protein-dependent pathways with equal potency, CCL19 but not CCL21 induced robust phosphorylation, β-arrestin-2 recruitment, and CCR7 desensitization [19]. In addition, CCL19-mediated ERK1/2 activation was partially mediated by β-arrestin-2. On the other hand, ERK1/2 activation was found to be completely dependent on Gαi activation. This suggests that CCL19-induced β-arrestin recruitment is triggered by phosphorylation of CCR7 by GRKs, which are activated in a Gαi-dependent manner. Indeed, it was found that activation by CCL19 or CCL21 leads to differential GRK specificity for CCR7 [20]. In this study, CCL19 induced robust phosphorylation of CCR7 and recruitment of β-arrestin-2 catalyzed by both GRK3 and GRK6, whereas CCL21 mediated phosphorylation and recruitment of β-arrestin-2 was less pronounced and involved only GRK6. However, solely CCR7 phosphorylation and β-arrestin-2 recruitment by CCL19 resulted in trafficking of CCR7 to endocytic vesicles and receptor desensitization. Both chemokines stimulated ERK1/2 involving GRK6 but not GRK3. Interestingly, GRK6 but not GRK3 is also important for β-arrestin-mediated ERK activation by β2-adrenergic receptors, indicating that this may be a common mechanism [8]. It has been suggested that GRK-specific phosphorylation patterns of the receptor may be interpreted as a “barcode” that instructs adapter proteins such as β-arrestins which conformation to adapt, and therefore which scaffolding functions to perform [20]. Such a GRK-induced barcode would also confer specificity to the many possible interactions with the wide range of scaffold proteins that have been described for 7TMRs.

Adenosine receptors

Four 7TMRs for the endogenous molecule adenosine 1 have been described, named adenosine receptor A1 (A1R), adenosine receptor A2A (A2AR), adenosine receptor A2B (A2BR), and adenosine receptor A3 (A3R; see Fig. 1 for structures of the ligands mentioned in this review) [21]. The best-known antagonist for A1R and A2R subtypes is caffeine, the active ingredient of coffee and tea. The adenosine A1R and A2AR are highly expressed in the brain, where adenosine is involved in sleep/wakefulness and modulation of neurotransmitter responses [21, 22]. A1Rs interact with various neurotransmitter systems such as dopamine D1 and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, while A2AR and D2R-mediated signaling are closely linked. In the periphery, A1Rs are expressed in adipose tissue and the atria of the heart where they are involved in for instance inhibition of lipolysis and bradycardia. In addition to the brain, A2ARs are highly expressed on leukocytes and platelets. A2BRs are ubiquitously expressed at low levels and found in higher levels in the intestine and bladder [21, 22]. Using an A2BR-knockout/reporter-gene knock-in mouse model, it was shown that the primary site of A2BR expression is the vasculature [23]. In addition to the vasculature, A2BR-gene promoter activity was high in macrophages [23]. The A3R is found in lung, liver, and other peripheral tissues, the brain, as well as on eosinophils and mast cells [21, 24].

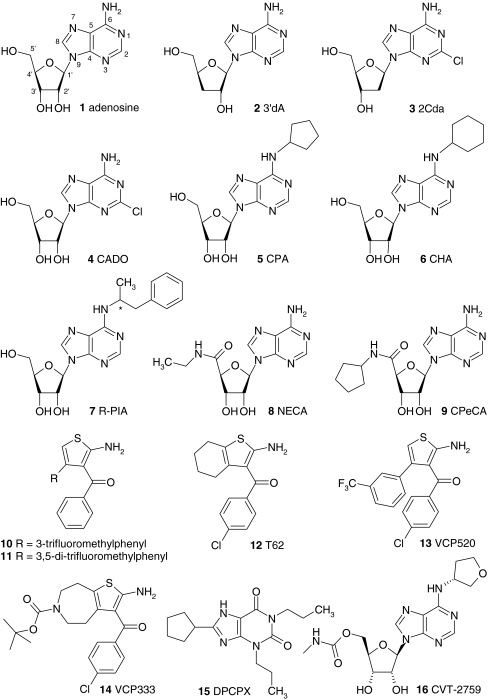

Fig. 1.

Adenosine receptor ligands. The structures of ligands that are mentioned in the text are shown. The ligands are indicated in the text with a bold number when they are mentioned for the first time. At moments when structural information can contribute to the discussion, the ligands are indicated in the text with a bold number as well. Abbreviations: 2CdA 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine, 3′dA 3′-deoxyadenosine, CADO 2-chloro-adenosine, CCPA 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine, CHA N6-cyclohexyladenosine, Cl-IB-MECA 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, CPA N6-cyclopentyladenosine, CPeCA 5′-N-cyclopentyl-carboxamidoadenosine, DBXRM 1,3-dibutylxanthine-7-riboside-5′-N-methylcarboxamide, DPCPX 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine, DPMA N6-[2-(3,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(2-methylphenyl)-ethyl]adenosine, IB-MECA N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, MECA 5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, NECA 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine, R-PIA N6-(1-methyl-2-phenylethyl)adenosine

Adenosine is present in all cells and extracellular fluids. During episodes of oxidative stress, ischemia and hypoxia the levels of adenosine increase, and activation of adenosine receptors is thought to play a protective role. Due to the broad expression of adenosine receptor subtypes, and the omnipresence of the endogenous agonist adenosine, selectivity of synthetic therapeutic adenosine ligands is very important. Such selectivity may sometimes be reached with receptor subtype-specific compounds (see references [14, 25] for an overview of adenosine receptor ligands), but becomes problematic if the same receptor mediates different physiological processes. However, if different processes downstream of the same receptor are involved in a pathological condition, biased compounds would have the potential to selectively activate the therapeutically relevant pathway without affecting other signal transduction routes. Moreover, since an antagonist for a G protein-mediated response can still be an agonist for β-arrestin-mediated signaling, it is important to know if a drug shows functional selectivity in order to predict and prevent adverse effects.

Adenosine receptors are tightly regulated in terms of desensitization and internalization, mediated by GRKs and β-arrestins (reviewed in [24]). It is therefore not improbable that biased adenosine receptor ligands exist, which selectively activate β-arrestin-mediated signal transduction pathways. Adenosine receptors have been reported to activate ERK1/2 in a variety of cell types, mediated by different downstream signaling components [26, 27]. Since both G protein-dependent and -independent pathways often come together at the level of ERK1/2, some special attention to this MAPK will be dedicated in the paragraphs below describing the individual adenosine receptors.

Dimerization and oligomerization of 7TMRs can also be seen as allosteric modulation of the receptor and often results in modified binding and signaling properties compared to the monomeric receptor. Homo- and heterodimerization of adenosine receptors have recently been reviewed [14, 28] and a complete overview would be beyond the scope of the current review.

A1 adenosine receptors

A1Rs couple to Gαi(1–3) proteins and Gαo, and their main effects are thought to be through the inhibition of intracellular cAMP levels [29]. In addition, release of βγ-subunits from pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gαi proteins can result in the activation of PLC isoforms, followed by formation of inositol phosphates and diacylglycerol, and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores [30]. The A1R activates ERK1/2 in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells as well as in a variety of other cell types [26, 27].

Functional selectivity of A1 adenosine receptors

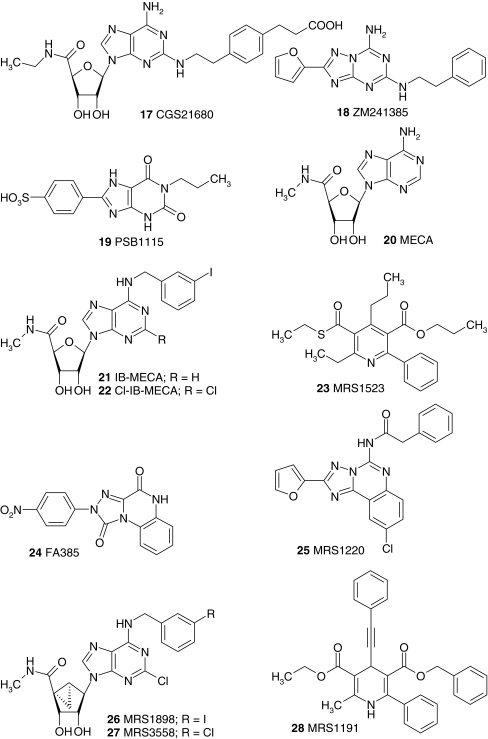

Besides the prototypical coupling of A1R to Gαi proteins, activation of Gαq and Gαs proteins [31] as well as promiscuous Gα16 proteins [32] has been reported (Fig. 2). The non-selective agonist NECA 8 and the A1R-selective agonists CPA 5 and R-PIA 7 were tested for their ability to stimulate Gαs and Gαq proteins after inactivation of Gαi proteins with PTX [31]. The experiments were performed in CHO cells expressing low (CHO-A1-low) and high (CHO-A1-high) amounts of the A1R. In PTX-treated CHO-A1-low cells, NECA enhanced forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation, while CPA and R-PIA were unable to activate Gαs proteins. In the cells with high A1R expression levels all three agonists induced cAMP formation, indicating that NECA has a higher intrinsic efficacy for the Gαs pathway than CPA and R-PIA. Indeed, in the CHO-A1-high cells NECA was the most efficacious agonist in stimulating Gαs-mediated cAMP accumulation compared to the other agonists, although it had the lowest potency. Similar to stimulation of Gαs proteins, NECA showed higher efficacy than CPA and R-PIA for PTX-insensitive Gαq-mediated inositol phosphates formation, again while having lower potency. The efficacies of the agonists for the traditional Gαi-mediated pathway were similar, and potencies found for Gαi-activation were approximately 200- to 1,200-fold higher than for Gαs-mediated signal transduction and 1,700- to 20,000-fold higher than for Gαq-mediated inositol phosphates accumulation. Although the A1R is expressed at high levels in this model, likely forcing the receptor to couple to G proteins which may not be activated in a more physiological setting, it appeared that NECA has a higher intrinsic activity for Gαq and Gαs than CPA en R-PIA (Fig. 2). In a follow-up study, a series of NECA and CPA analogs was tested in order to elucidate the structure-activity relationship underlying this functional selectivity [33]. All tested compounds were full agonists in the Gαi-mediated inhibition of cAMP. Interestingly, the NECA-analog CPeCA 9, bearing a cyclopentyl instead of an ethyl group at the 5′-N-position of NECA, showed higher efficacy for the Gαs pathway than for the Gαq pathway. Binding of NECA to the A1R is crucially depending on threonine residue T7.42 (T277) in TM7, as mutation of this residue abolishes binding for NECA, but not for R-PIA (7TMR numbering according to reference [34]). R-PIA 7 has an intact ribose group and is less efficacious in activating Gαq and Gαs than NECA 8. Therefore interaction of the 5′-N-substituents of NECA 8 and CPeCA 9 with T7.42 may be involved in functional selectivity towards PTX-insensitive pathways.

Fig. 2.

Functional selectivity of the adenosine A 1 receptor. The A1R can activate Gα s and Gα q/11 proteins besides the classical Gα i pathway. The non-selective agonist NECA has higher intrinsic activity for these alternative pathways than A1R-selective agonists. The intrinsic activities of A1R-selective agonists such as CHA, CPA, and CPeCA for the alternative G proteins differ amongst each other as well. Allosteric modulators such as 2A3BT-class PAMs can bias signaling of orthosteric ligands. The endogenous enzyme ADA appears to function as a natural extracellular allosteric modulator of A1Rs, possibly in close cooperation with the intracellular scaffold protein Hsc73. Signaling through G proteins and β-arrestins converges at the level of ERK1/2 activation. Interaction with scaffold proteins like 4.1G protein may favor functional selectivity by stabilizing distinct receptor conformations. See references in the text for more detailed information

The A1R-selective CPA-analog CHA 6, which has a cyclohexyl instead of a cyclopentyl group at the N6-position of adenosine, was more efficacious than CPA 5 in activating Gαs and Gαq, indicating that substitution at this position may induce functional selectivity too. This hydrophobic N6-moiety has been suggested to interact with amino acids in the TM3 domain of the receptor such as L3.33 (L88) and to confer A1R-selectivity to ligands [35]. Differential interaction of the N6-cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl group of CPA 5 and CHA 6 with L3.33 may therefore underlie the observed differences in efficacy by stabilizing different receptor conformations.

That PTX-insensitive pathways can be physiologically relevant is illustrated by the A1R-mediated activation of the transcription factor NF-κB by CHA, through proteins of the promiscuous Gα16 class in the human lymphoblastoma Reh cell line [36]. Gα16 proteins are mainly expressed in hematopoietic cells and the agonist-dependent differences in efficacy between PTX-sensitive and PTX-insensitive responses described above raise the question if functionally selective compounds can be designed that specifically target these Gα16-mediated pathways.

A series of 4-substituted 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophenes (2A3BTs) was tested for their ability to act as allosteric enhancers of ERK1/2 activation by the orthosteric A1R-selective ligand R-PIA [37]. Two compounds showed allosteric enhancement of R-PIA-induced ERK1/2 activation, as well as partial agonism in the absence of R-PIA. These compounds, with 3-trifluoromethylphenyl 10 [38] and 3,5-di-trifluoromethylphenyl 11 substituents of the 4-position, were additionally tested in a [35S]GTPγS binding assay. Using an operational model of allosterism it was calculated that the 3-trifluoromethylphenyl substituted compound 10 showed a significant difference in positive cooperativity between enhancement of R-PIA-induced ERK1/2 activation and [35S]GTPγS binding. The authors suggested that this allosteric enhancer displays functional selectivity with respect to the amount of allosteric potentiation, depending on the pathway that is investigated.

The observation that the 2A3BT-class of allosteric enhancers may bias the signaling of the orthosteric ligand towards a certain signal transduction pathway was further investigated with another panel of allosteric modulators, i.e., T62 12, VCP520 13, and VCP333 14 [39]. All allosteric compounds acted as partial agonists for ERK1/2 activation and for inhibition of cAMP accumulation in the absence of the orthosteric agonist R-PIA in intact CHO cells, except for VCP333 which was almost devoid of ERK1/2 signaling. The compounds were inactive in an intracellular Ca2+ mobilization assay in the absence of R-PIA. Surprisingly, while the potency of the orthosteric ligand R-PIA was about tenfold higher for ERK1/2 activation than for inhibition of cAMP, the opposite was true for the allosteric partial agonists that were more potent for the inhibition of cAMP than for ERK1/2 activation. This is a typical example of functional selectivity and indicates that the allosteric ligands bias A1R signaling towards different pathways than R-PIA, by stabilizing different receptor conformations compared to the orthosteric ligand. When tested in the presence of R-PIA, the allosteric compounds enhanced the potency of R-PIA-mediated signaling and in addition increased the efficacy for Ca2+ mobilization. Using the operational model of allosterism, it was calculated that the VCP520-mediated potentiation of R-PIA signaling in the Ca2+ mobilization assay was significantly greater than for ERK1/2 activation, again pointing towards functional selectivity. VCP520 13 differs only in one atom from the abovementioned 3-trifluoromethylphenyl substituted 2A3BT 10 [37] (i.e., a chloro vs. a hydrogen at the 4-position of the benzoyl group), suggesting that the 3-trifluoromethylphenyl substituent of the 2A3BT may be of importance for functional selectivity of 2A3BTs. The same laboratory also observed that the 2A3BT class of allosteric modulators has a receptor-independent effect as inhibitors of an intracellular component at the level of G proteins, when used at higher concentrations in membrane preparations but not in intact cells [39]. This finding indicates that care must be taken in the choice of assay used to determine the effects of 2A3BTs.

β-arrestins

In addition to coupling to G proteins, A1Rs can interact with several other proteins, raising the possibility to signal through G protein-independent pathways (Fig. 2). Interaction of GPCRs with β-arrestins is one of the best-described pathways through which ligands may demonstrate functional selectivity. Upon stimulation of the A1R with the A1R-selective agonist R-PIA in CHO cells, β-arrestin-2 was redistributed from the cytoplasm to punctuate spots located near the plasma membrane [40]. Surprisingly, no internalization of A1R was detected, and there was no significant overlap between the localization of A1R and β-arrestin-2. On the other hand, knock-down of β-arrestin-1 in Syrian hamster ductus deferens smooth muscle tumor (DDT1 MF-2) cells almost completely abrogated downregulation of the A1R upon 24-h stimulation with R-PIA [41]. Short-term stimulation of DDT1 MF-2 cells with R-PIA resulted in a rapid translocation of β-arrestin-1 to the membrane. Stimulation of these cells with R-PIA also resulted in a rapid and transient ERK1/2 activation, which was abolished after knock-down of β-arrestin-1, indicating that A1 can activate ERK1/2 via β-arrestin-1. This is in contrast with the observation that ERK1/2 activation by β-arrestin often results in a sustained second phase of ERK1/2 phosphorylation [6, 8]. Nevertheless, this β-arrestin-mediated activation of ERK1/2 is of particular interest since ERK1/2 activation may be important for the cardioprotective effect mediated by A1Rs during ischemia/reperfusion [42–44]. Agonists for the A1R that show functional selectivity for the β-arrestin/ERK pathway may therefore be useful for cardioprotection, provided that β-arrestin-mediated ERK activation indeed is part of the mechanism of cardioprotection. This may not be the case, as ERK1/2 activation in rat cardiomyocytes was shown to be completely sensitive to treatment with PTX, and was suggested to involve βγ-subunits from Gi proteins, genistein-sensitive Src tyrosine kinases, PKC, and PLC instead of β-arrestins [44].

Although A1R-mediated ERK1/2 activation has been shown to be dependent on either G proteins or β-arrestins, no biased ligands have been reported that favor one pathway over the other.

Internalization by adenosine A1 receptors antagonists

Ligand-induced internalization of GPCRs can occur independently of G protein activation, for instance by stabilizing receptor conformations that promote β-arrestin recruitment and internalization. Both the agonist R-PIA and the A1R antagonist/inverse agonist DPCPX 15 induced internalization of A1Rs in rat GH4 pituitary cells [45]. In contrast, incubation of DDT1 MF-2 cells with R-PIA resulted in downregulation, while DPCPX induced upregulation of A1Rs [46]. The upregulation of A1Rs by the inverse agonist/antagonist DPCPX in DDT1 MF-2 cells can be explained by stabilization of the receptor and is more often observed for inverse agonists [47]. However, the observed downregulation by the inverse agonist/antagonist DPCPX in rat GH4 cells suggests a G protein-independent mechanism, indicating that DPCPX may display functional selectivity through for instance β-arrestin-mediated pathways.

Full agonists versus partial agonists

A different method of reaching tissue-selective effects of A1R agonists has been through the use of partial agonists instead of full agonists. Agonists of A1Rs may be useful in the treatment of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus because of their anti-lipolytic effects. However, the expression of A1Rs in the body is widespread and selective anti-lipolytic action seems to be hard to obtain. More importantly, stimulation of A1Rs in the heart by full agonists can lead to adverse cardiovascular effects such as severe bradycardia and AV block. In order to be useful in the treatment of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, the cardiac side effects have to be separated from the anti-lipolytic properties. Interestingly, several 8-alkylamino-substituted analogs of the agonist CPA 5 showed less-pronounced decreases in heart rate and mean arterial pressure than CPA itself when tested in vivo in rats, acting as partial agonists on these responses [48]. When these CPA analogs were tested for their anti-lipolytic effects in vivo, it was found that they reduced lipolysis to levels which were almost comparable to the full agonist CPA, although they are partial agonists with respect to lowering the heart rate [49]. The selectivity between bradycardia and anti-lipolytic effect was dependent on differences in potency and intrinsic activity of the CPA analogs for the two effects. This intriguing finding was explained by the difference in receptor reserve between heart tissue and adipose tissue. Depending on the amount of receptors present in a tissue and their efficiency in coupling to a certain intracellular response, low-efficacy agonists can act as full agonists, partial agonists, or antagonists. Therefore, it is possible to develop anti-lipolytic effects without severe cardiovascular effects, making use of the fact that receptor reserve in adipose tissue is higher than in cardiac tissue [49]. Similarly, the negative effects of A1R agonists on the cardiovascular system hamper the development of A1 agonists as potential antiarrhythmic drugs. It has been suggested that this problem can be overcome by the development of partial A1R agonists, which may moderately slow AV conduction time and control ventricular rate during periods of atrial tachycardias, without causing serious cardiovascular side effects. For instance, CVT-2759 16 was identified as a partial agonist compared to the full agonist CPA 5 for slowing AV nodal conduction in guinea pig isolated hearts, without causing AV block or severe slowing of atrial rate [50]. This effect is also attributed to the relatively low expression of A1Rs in the heart, resulting in an absence of receptor reserve. Indeed, when tested in Fisher rat thyroid (FRTL-5) cells or rat epididymal adipocytes which have higher A1R expression, CVT-2759 acted as a full agonist [50]. These results indicate that partial A1R agonists may also be useful as antiarrhythmic drugs. The tissue-selective effects of partial agonists described in this paragraph should not be mistaken for functional selectivity, as the observed selectivity solely relies on differences in receptor density between tissues.

Indications of functional selectivity at adenosine A1 receptors

There are some additional indications that A1Rs have the potential to direct extracellular signals to specific pathways. For instance, overexpression of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) inhibited Gβγ-mediated ERK1/2 activation, but not Gαi-mediated inhibition of cAMP in FRTL-5 cells [51]. Expression of GRK2-K220R, a kinase-dead dominant negative mutant of GRK2, did not influence ERK1/2 activation or cAMP reduction, indicating that the regulation of ERK1/2 activity was not due to βγ-scavenging by GRK2. It was suggested that the differential regulation of ERK1/2 and cAMP is due to the ability of GRK2 to phosphorylate the A1R in a manner that affects Gβγ-mediated signaling but not Gαi-mediated signaling. Adenosine and CPA were used as agonists in this study, and it would be interesting to see if other ligands would be able to influence this GRK2-mediated bias in signaling.

Another example of an endogenous protein that can influence A1R signaling is the ectoenzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA) which breaks down adenosine into inosine (Fig. 2). This enzyme is often added to in vitro studies with adenosine receptors in order to prevent effects of endogenous adenosine. ADA interacts directly with the A1R in pig brain cortical membranes and DDT1 MF-2 cells and interestingly the interaction of ADA with an extracellular domain of the A1R is necessary to induce the G protein-coupled high-affinity state of the receptor [52, 53]. Human ADA was shown to increase both agonist and antagonist binding on human brain striatal membranes, and to act as a positive allosteric modulator by increasing the potency of R-PIA more than tenfold in CHO cells [54]. While ADA increases binding of agonists and antagonists to the A1R, it was shown to decrease binding of the pig A1R to the heat shock cognate protein Hsc73 [55]. Hsc73 by itself reduces binding of the agonist R-PIA and the A1R-selective inverse agonist DPCPX and reduces activation of G proteins through an interaction with the third intracellular loop of the A1R [55]. The Hsc73-mediated reduction in binding of R-PIA and DPCPX could be reversed by addition of ADA. Since ADA binds to an extracellular domain [53] and Hsc73 to the third intracellular loop, it was suggested that binding of ADA affects the structure of the third intracellular loop, thereby inhibiting binding of Hsc73 [55]. If Hsc73 acts as an inhibitor of ligand binding to the A1R, the release of Hsc73 upon incubation with ADA may explain the positive effects that ADA has on ligand affinity and potency. Both proteins appear to be involved in internalization processes of the receptor. ADA enhanced and accelerated R-PIA-induced phosphorylation of the A1R and increased the rate of desensitization and internalization [56]. In addition, ADA colocalizes with the A1R on the plasma membrane and in intracellular vesicles upon R-PIA-induced internalization. Hsc73 also colocalizes with the A1R on the plasma membrane, but upon internalization into intracellular vesicles, Hsc73 is only found together with the A1R in some of the A1R-containing vesicles. The authors suggested that binding of ADA to the extracellular domain of the A1R may prevent association of Hsc73 during sequestering into intracellular vesicles, resulting in different A1R trafficking depending on the presence of ADA or Hsc73. Hsc73 is also involved in internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, and knock-down of Hsc73 inhibits CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis without affecting ligand binding, indicating the potential regulation of signaling pathways by this heat shock protein [57]. It is unknown if ADA or Hsc73, which can be considered endogenous allosteric modulators, can bias signaling of orthosteric A1R agonists towards a preferred intracellular pathway, analogous to the synthetic allosteric modulators of the 2A3BT class described above.

Upon stimulation of the A1R with R-PIA in pig kidney epithelial LLC-PK cells, the A1R and ADA aggregate on the cell surface and translocate into intracellular compartments [58]. In these intracellular vesicles, the A1R was found to colocalize with caveolin and to interact with caveolin-1 through its C-terminal domain. Caveolins are an important component of caveolae, which are microdomains in the cell membrane that orchestrate signal transduction and receptor trafficking. Further interactions of the A1R with caveolins have been reported for caveolin-1 [59] and caveolin-3 [60]. Interaction of the A1R with proteins of the caveolin family implies localization of A1Rs in these microdomains, where they can activate caveolae-specific pathways that may not be available in other subcellular compartments, for instance regulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels [60]. Surprisingly, A1Rs have been shown to leave caveolae upon activation by agonists [61]. Caveolae contain members of the MAPK family as well, and besides interacting with the A1R, caveolin-3 interacts directly with ERK2 but not ERK1 in rat cardiomyocytes [62]. The A1R agonist CCPA stimulated phosphorylation of both ERK1 and ERK2 in cytosolic fractions of these cells, whereas in caveolin-3 enriched fractions phosphorylation of ERK2 was reduced and phosphorylation of ERK1 was unchanged.

In a yeast two-hybrid screen an interaction of the third intracellular loop of the rat A1R with the cytoskeletal 4.1G protein was identified [63] (Fig. 2). Colocalization of A1Rs and 4.1G was shown in the mouse cerebral cortex microglia as well [64]. Cotransfection of the rat A1R and 4.1G protein in HEK293 cells resulted in a remarkable loss of binding of the inverse agonist [3H]-DPCPX, observed as a 40-fold lower B max and almost 60-fold increase in K d compared to cells expressing the A1R alone. The ability of the agonist CPA to inhibit forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation in CHO cells cotransfected with 4.1G protein was reduced by approximately 50%, whereas mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ by CPA was completely abolished. This suggests that binding of 4.1G to the A1R affects calcium mobilization more than cAMP inhibition, and may indicate that the 4.1G protein induces functional selectivity for CPA. However, these differences may also arise from the type of assay or concentration of CPA that was used in the assays. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that the localization of A1Rs in subcellular compartments such as caveolae can contribute to activation of specific pathways (such as K+ channels) and to differential regulation of ERK1/2. Scaffolding proteins such as caveolins or 4.1G may also stabilize conformations of the receptor that may be preferred by some ligands over other confirmations, thereby inducing functional selectivity. However, such ligands have yet to be identified.

A2A adenosine receptors

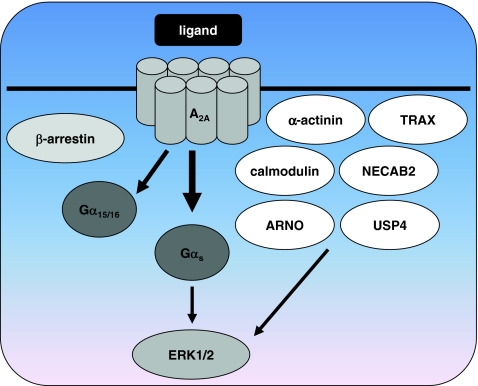

The A2AR is coupled to Gαs and Golf proteins [65, 66], but has also been reported to interact with hematopoietic Gα15/16 proteins [67] (Fig. 3). Activation of ERK1/2 in CHO cells expressing the A2AR is biphasic and less pronounced than activation mediated through the Gαi-coupled A1R or A3R [27, 68]. The mechanism of ERK1/2 activation by A2ARs was compared between transfected HEK293 and CHO cells and appeared to be highly cell-type dependent [26, 69]. In CHO cells, A2AR-mediated ERK1/2 activation was Gαs-dependent, while in HEK293 cells Gαs-, Gαi-, and PKC-independent ERK1/2 activation was observed that required p21ras [69, 70]. It was suggested that A2ARs may couple to Gα12/13 proteins in HEK293 cells, or activate ERK1/2 through G protein-independent pathways. ERK1/2 activation by the A2AR/A3R-selective agonist CGS21680 17 in CHO cells was shown to be mediated via a Gαs/cAMP/PKA/Src-like kinase dependent pathway [68]. Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) play an important role in the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis because they produce matrix proteins such as collagen after activation. Collagen type I expression by HSC upon stimulation of A2AR with CGS21680 was shown to be regulated by a pathway involving PKA, Src, and ERK1/2, whereas collagen type III depended on activation of p38 MAPK but not PKA, Src, and ERK1/2 [71]. It is not known at which level the ERK1/2 and p38 pathways activated by the A2AR start to diverge. If they diverge at the level of the A2AR itself, it may be possible to selectively activate either the ERK1/2 or p38 with biased ligands in these cells.

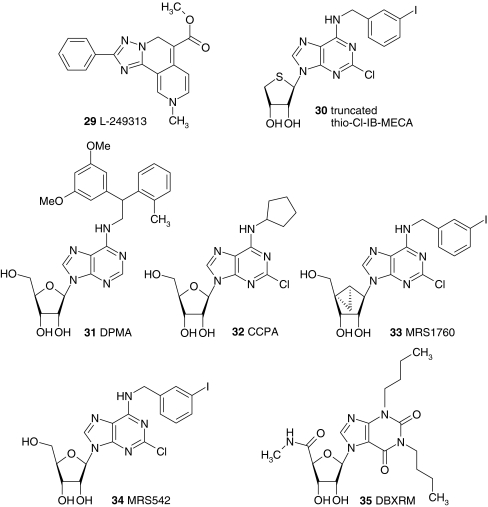

Fig. 3.

Potential for functional selectivity of the adenosine A 2A receptor. Although no functionally selective ligands for the A2AR have been identified to date, this adenosine receptor in particular bears potential for biased signaling. Its exceptionally long carboxyl terminus interacts with a variety of scaffold proteins such as β-arrestins, α-actinin, ARNO, calmodulin, NECAB2, USP4, and TRAX. Besides the classical activation of Gα s proteins by A2ARs, interaction with Ga 15/16 proteins of the Gαq/11 family has been reported. Both G protein-dependent and -independent pathways can lead to phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by A2AR. Several lines of research indicate that interaction with scaffold proteins tethers A2ARs to microdomains in the plasma membrane, where they may engage selective signal transduction pathways. See references in the text for more detailed information

In contrast to the other adenosine receptors, which have C-terminal tails of about 30–40 amino acids, the carboxyl terminus of the A2AR consists of 122 amino acids. This long C-terminal tail offers the opportunity to interact with many intracellular proteins that may stabilize receptor conformations required for functional selectivity or mediate G protein-independent signaling. There is a rapidly expanding list of proteins that have been shown to interact with the C-terminus of the A2AR including α-actinin [72], ARNO/cytohesin-2 [73], the de-ubiquinating enzyme ubiquitin-specific protease 4 (USP4) [74], translin-associated protein X (TRAX) [75], neuronal Ca2+-binding protein 2 (NECAB2) [76], and calmodulin [77] (Fig. 3). In addition, a recent review about proteins that interact with the A2AR C-terminus describes neuroendocrine-discs large homolog 3/synapse-associated protein 102 (NE-DLG/SAP102), 14.3.3 protein-θ/τ and astrin as candidate proteins [78]. Translocation of β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 upon stimulation of transfected HEK293 cells with the agonist CGS21680 indicates that the A2AR interacts with β-arrestins as well [72].

The importance of the C-terminus for the activation of distinct signal transduction pathways was shown using C-terminally truncated versions of the receptor [79]. Truncation of the A2AR blunts constitutive cAMP formation in intact HEK293 cells, but leaves ERK1/2 activation unaffected. When using membranes instead of intact cells, no differences in constitutive G protein activation could be observed between WT and truncated receptors, suggesting an intracellular component that binds to the C-terminus in intact cells and stabilizes the signaling complex responsible for ERK1/2 activation [79]. Since binding of any of these adapter proteins may mediate biased signaling, they will be described in more detail in the following sections.

ARNO, α-actinin, and calmodulin

A possible explanation for the G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation described above is binding of ARNO, also named cytohesin-2, to the C-terminus of the A2AR [73]. ARNO is a nucleotide exchange factor for the small G proteins of the ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) family, i.e., ARNO catalyzes the replacement of GDP by GTP at these monomeric G proteins. ARNO was picked up during a yeast two-hybrid screen and interacts with the membrane proximal part of the C-tail of the A2AR that is forming the intracellular helix 8. Expression of ARNO or a dominant negative form of ARNO had no effect on the expression levels of the A2AR, the affinity of the inverse agonist radioligand [3H]-ZM241385 18 [80], Gαs-dependent accumulation of cAMP, or receptor desensitization in HEK293 cells [73]. Activation of ERK1/2 after 5-min stimulation with the selective A2AR/A3R agonist CGS21680 was also not affected. However, expression of the dominant negative mutant of ARNO inhibited sustained ERK1/2 activation upon longer stimulation times. These effects were likely mediated through interactions of ARNO with ARF6, since a dominant negative mutant of ARF6 also inhibited sustained ERK1/2 activation. Although ARNO-mediated signaling only explains the sustained ERK1/2 activation, and not the initial raise in ERK phosphorylation, it is a good example of G protein-independent signal transduction and suggests possibilities for agonists that selectively activate this pathway.

In the example above, expression of the dominant negative mutant of ARNO affected sustained ERK1/2 activation in HEK293 cells, but not Gαs-mediated signaling. In contrast, depletion of cholesterol inhibits coupling of the A2AR to Gαs in HEK293 cells, while leaving Gαs-independent ERK1/2 activation unaffected [81]. Therefore it seems that cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains are required for the interaction of the A2AR with Gαs proteins but not for the activation of ERK1/2. It is tempting to speculate that such a Gαs- and cholesterol-independent ERK1/2 activation is mediated by ARNO. A very remarkable feature of the A2AR is its tight precoupling to the Gαs protein [82]. This phenomenon is referred to as restricted collision coupling, indicating that encounters between the agonist-occupied A2AR and Gαs proteins do not occur at random at the cell membrane, but by keeping the interaction partners in close proximity in microdomains. These microdomains may for instance be cholesterol-rich lipid rafts, which would explain the diminished interaction of A2AR and Gαs upon depletion of cholesterol [81]. Microdomains form an excellent platform for functionally selective ligands, since in microdomains receptors only encounter selected G proteins that are present in these rafts such as Gαs, but not other proteins such as Gα15/16 or ARNO, resulting in selective responses.

One of the proteins that may be necessary for the localization of A2ARs in microdomains is α-actinin, by tethering the A2AR to the cytoskeleton [78]. The cytoskeletal protein α-actinin is involved in F-actin crosslinking and was shown to interact with the C-terminal end of A2ARs [72]. In addition, treatment of HEK293 cells expressing the A2AR with cytochalasin D, which causes disruption of actin filaments and inhibition of actin polymerization, inhibits internalization of the A2AR indicating a functional relationship between A2ARs and the underneath actin structure [72]. That the interaction of A2ARs with the cytoskeleton via α-actinin may be physiologically important was shown in rat neostriatal neurons, which express the A2AR endogenously [83]. Activation of A2ARs by CGS21680 inhibits an NMDA-induced current in these neurons. The A2AR-mediated inhibition of this current was abolished upon treatment with cytochalasin B that enhances actin depolymerization, indicating an important interaction between the A2AR and the cytoskeleton which may be mediated by α-actinin. In addition to cytochalasin B, application of the calmodulin antagonist W-7 eliminated the A2AR-mediated inhibition of NMDA-induced current in rat neostriatal neurons [83]. Using several other inhibitors of signal transduction components, the authors found that A2AR-mediated inhibition of NMDA channels occurs via a pathway involving PLC/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate/calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II.

Remarkably, one of these signaling components, calmodulin, was recently shown to interact directly with the C-terminus of A2ARs [77, 84]. Calmodulin is an intracellular Ca2+-binding protein that plays a central role in Ca2+ signaling and binds the A2AR at the membrane proximal domain including part of helix 8. When the A2AR and calmodulin were coexpressed in HEK293 cells, it was found that changes in intracellular Ca2+ lead to conformational changes in the calmodulin-A2AR heterodimer. In addition to calmodulin, A2ARs have been reported to heterodimerize with other GPCRs such as the dopamine D2R [14, 28, 85]. Calmodulin appears to interact with the A2AR-D2R dimer to form a calmodulin-A2AR-D2R oligomer [84]. Even though changes in intracellular Ca2+ lead to a conformational change in the calmodulin-A2AR complex, variations in intracellular Ca2+ did not lead to modified ERK1/2 phosphorylation after activation of the A2AR with CGS21680. In contrast, upon cotransfection of the D2R, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ negatively influenced the ability of the calmodulin-A2AR-D2R oligomer to activate ERK1/2 upon stimulation with CGS21680, while positively modulating ERK1/2 activation after stimulation with the D2R agonist quinpirole [84]. Therefore it seems that calmodulin modulates ERK1/2 activation initiated by the calmodulin-A2AR-D2R oligomer, but not that of the calmodulin-A2AR heterodimer.

ARNO, α-actinin, and calmodulin all bind to the same domain at the A2AR C-terminus that includes part of helix 8, and it is unlikely that they do so simultaneously [78]. These adapter proteins may therefore interact with the A2AR at specific time points during receptor activation, or depending on their availability in the cellular background. It can also be envisioned that certain ligands stabilize receptor conformations that favor binding of one of these adapter proteins over the others, resulting in a ligand-dependent activation of for instance ERK1/2.

NECAB2 and TRAX

In addition to calmodulin, another Ca2+-binding protein was shown to interact with the C-terminus of the A2AR. NECAB2 is a neuronal protein that was picked up during a yeast two-hybrid screen with the A2AR C-tail as bait [76]. Increasing concentrations of Ca2+ inhibited the binding of the A2AR to NECAB2. Coexpression of NECAB2 and A2ARs in HEK293 cells resulted in a decrease in A2AR cell surface expression in combination with intracellular retention of the A2AR. Stimulation of cells expressing the A2AR alone with the agonist CGS21680 resulted in a time-dependent decrease in cell surface expression of the receptor. Intriguingly, when the A2AR and NECAB2 were coexpressed, CGS21680-treatment for 2 h resulted in a marked increase in cell surface expression of A2ARs. In addition, coexpression of NECAB2 and A2ARs significantly potentiated ERK1/2 activation after incubation with CGS21680 [76]. These results illustrate once more how binding of intracellular proteins to the C-terminus of the A2AR can influence signaling. The observation that increasing Ca2+ concentrations disrupt the interaction between the A2AR and NECAB2 suggests a dynamic fine-tuning of A2AR signaling by NECAB2, similar to the Ca2+-dependent regulation of ERK1/2 activation by the calmodulin-A2AR-D2R oligomer [84].

Finally, interaction of the A2AR C-terminus with TRAX has been reported. It rescues the nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced differentiation process impaired by inactivation of the transcription factor p53 in rat adrenal pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells, which are used as a model system for neuronal differentiation [75]. NGF induces neuronal differentiation in PC-12 cells via multiple pathways, such as the ERK1/2 and p53/p21 pathway. When the ERK1/2 pathway is blocked, stimulation of the A2AR can rescue neuronal differentiation via a cAMP/PKA/CREB-dependent pathway in PC-12 cells [86]. However, A2AR-mediated rescue of the differentiation process when p53 signaling was blocked was found to be independent of PKA and to be mediated by TRAX [75]. TRAX binds to several proteins, among which translin and the kinesin heavy chain member KIF2A. KIF2A but not translin was shown to mediate the rescue effect of the A2AR upon p53 impairment in PC-12 cells and primary rat hippocampal neurons [87]. Therefore rescue of a damaged p53 pathway, which may occur pathologically, is mediated through an A2AR/TRAX/KIF2A pathway and may contribute to the neuronal protective effects of A2ARs. Since p53, TRAX, and KIF2A have been implicated in schizophrenia and the A2AR is a potential target for the treatment of schizophrenia [87], it can be speculated that selective activation of the A2AR/TRAX pathway by biased agonists may be beneficial in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Summarizing, although the A2AR has much potential for G protein-independent signaling pathways through its extraordinary long carboxyl terminus, to date specific regulation of these pathways by biased ligands has not been reported.

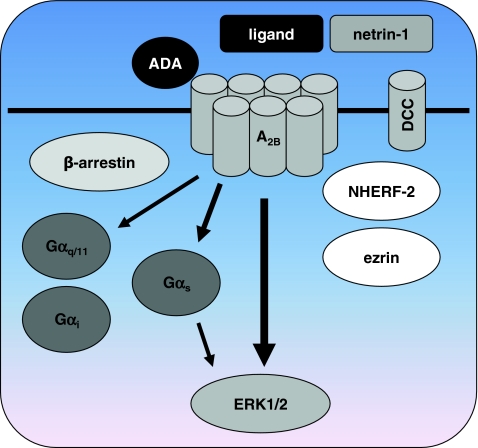

A2B adenosine receptors

The A2BR is described mainly as a Gαs-coupled 7TMR [22], although coupling to G proteins of the Gαq class has also been described [88–90] (Fig. 4). In the Jurkat T cell leukemia cell line, Ca2+ responses were partially sensitive to PTX, suggesting coupling to Gαi proteins as well [91]. In transfected CHO cells, A2BR activation resulted in ERK1/2 activation that was slightly lower than ERK1/2 activation by the A2AR and considerably lower than by A1Rs or A3Rs [27]. The non-selective agonist NECA stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation via all four adenosine receptors with nanomolar potencies, but the potency of NECA in CHO-A2B cells for stimulating ERK1/2 (19 nM) was over 70-fold higher than for cAMP accumulation (1.4 μM). Stimulation of the A2BR with NECA in CHO cells resulted in cAMP-mediated activation of the MAPK p38 as well, with an EC50 value similar to that of ERK1/2 activation [92]. However, the pathways downstream of cAMP are different, i.e., ERK1/2 activation was mediated via PI3K, while p38 phosphorylation depended on PKA activity in CHO cells [92]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) ERK1/2 activation was Gαs/cAMP mediated and not dependent on PKC, making it unlikely that Gαq or Gαi proteins are involved in this pathway [93].

Fig. 4.

Potential for functional selectivity of the adenosine A 2B receptor. Similar to the A2AR no functionally selective ligands have been identified for the A2BR. Besides coupling of the A 2B R to Gα s, coupling to Gα q/11 and possibly Gα i proteins has been described. ERK1/2 is activated with a remarkably higher potency than observed for Gαs-mediated cAMP accumulation, indicating divergent signal transduction pathways that potentially can be regulated with biased ligands. Interaction with the extracellular proteins ADA and netrin or with the membrane-bound netrin-receptor DCC may influence A2BR signaling in an allosteric manner. In addition, DCC and A2BR both bind the intracellular proteins ezrin and NHERF-2 that may be involved in anchoring A2BR to the cytoskeleton and/or forming a signaling complex. See references in the text for more detailed information

Based on cAMP measurements it has previously been assumed that the A2BR is only activated at very high, pathophysiological concentrations of adenosine, while the other three receptors are activated at physiological concentrations of adenosine. The discrepancy between potency for the cAMP and ERK1/2 pathways indicates that amplification of the ERK1/2 signal takes place, or that A2BR preferentially activates the ERK1/2 pathway over Gαs.

G protein-independent interactions

One of the non-G proteins that have been described to interact with the A2BR is the receptor for netrin-1, also called deleted-in-colorectal-cancer (DCC) [94] (Fig. 4). Netrins are secreted proteins that are important in axon guidance. Interaction of the netrin-1 receptor DCC with the C-terminus of the A2BR was found during a yeast two-hybrid screen, using the intracellular domain of DCC as bait. Interestingly netrin-1, the ligand for DCC, was shown to activate A2BRs directly as well, apparently acting as a positive modulator at a site different from the binding site of the agonist NECA [94]. Netrin-1 increased binding of 3H-NECA to A2BR-transfected HEK293T cells in a concentration-dependent manner, which is an indication of allosteric modulation of A2BR by netrin-1. In HEK293T cells transfected with the A2BR, both addition of NECA and coexpression of the secreted protein netrin-1 resulted in increased cAMP levels. When NECA was added to HEK293T cells coexpressing both the A2BR and netrin-1, an additive effect of NECA and netrin-1 on cAMP accumulation was observed. Similarly, in the DCC-deficient adenocarcinoma HCT8/S11 cell line simultaneous addition of NECA and netrin-1 resulted in additive pro-invasive activity, although no significant additive effects on cAMP generation were observed [95]. This suggests that netrin-1 may act as an allosteric modulator of A2BR-mediated pro-invasive activity but not cAMP accumulation, or that netrin-1 and A2BRs activate distinct but convergent signaling pathways to induce invasion in HCT8/S11 cells. It was found that the A2BR is directly involved in netrin-1-dependent outgrowth of dorsal spinal cord axons [94], a finding that later was disputed by another group [96]. A direct interaction of netrin-1 with the A2BR was also suggested to be involved in the modulation of transepithelial migration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) [97]. In PMNs, the A2BR antagonist PSB1115 19 blocked netrin-1-mediated increases in cAMP concentrations, indicating that netrin-1 directly interacts with A2BRs [97].

Others reported that the A2BR does not bind netrin-1, but that A2BR activity by itself can regulate axonal responses to netrin-1 [98]. Activation of the A2BR by the agonists MECA 20 and NECA or by A2BR overexpression was found to be responsible for downregulation of another netrin-1 receptor named UNC5A, thereby modulating netrin-1 responses [98]. Additional support for an interaction between the netrin-1 receptor DCC and A2BRs is the fact that they interact with the same proteins. DCC was shown to interact with ezrin, a PKA-anchoring protein that is associated with the actin cytoskeleton [99]. Interestingly, the human A2BR also associates with ezrin upon activation with adenosine, as well as with NHERF-2 (Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2) [100]. It was suggested that the A2BR may be anchored to the membrane by NHERF-2, and form a signaling complex with ezrin, adenylate cyclase, and PKA [100]. Through its interaction with ezrin, DCC may also be part of this complex. In contrast, the rat A2BR co-immunoprecipitates with NHERF-1 and this interaction is reduced upon activation with the agonist NECA [101]. Overexpression of NHERF-1 inhibited internalization of rat A2BRs and a role for this scaffolding protein in rat A2BR recycling has been proposed [101].

Taken together, there is evidence that the A2BR is involved in netrin-1 signaling. It is however not clear if this occurs through a direct interaction of netrin-1 and the A2BR, the involvement of an A2BR/DCC/netrin-1 complex or A2BR-mediated modulation of netrin-1 receptor expression levels. If netrin-1 or DCC indeed acts as allosteric modulators of A2BRs [94], it may well be possible to influence such a complex with functionally selective ligands.

Furthermore, the A2BR has been described to interact with proteins involved in desensitization, internalization, and intracellular trafficking, such as β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 [102, 103], vesicle-associated membrane protein [104] and soluble NEM-sensitive factor attachment protein [104]. An intact C-terminal PDZ motif of the rat A2BR was found to be important for β-arrestin-1 and clathrin-mediated internalization, while disruption of this motif did not affect dynamin-dependent internalization [101]. This stresses the importance of the interaction of the intracellular tail of the A2BR with adapter proteins and the possible opportunities to intervene in these processes with functionally selective ligands.

Besides protein–protein interactions with the intracellular domain of the A2BR, the extracellular parts of A2BRs were shown to bind to ADA [105], similar to the findings for the A1R [52, 53]. Whereas cell surface expression of endogenous ADA is not detectable on control CHO cells, transfection of CHO cells with the A2BR results in extracellular expression of ADA [105]. Total binding of 3H-NECA to CHO cells transfected with the A2BR was concentration-dependently enhanced by addition of ADA, and the affinity of NECA was increased in the presence of ADA. In addition, cAMP production by NECA was increased as well in the presence of ADA. These results point toward an allosteric modulation of A2BRs by ADA, similar as was found for the interaction of ADA with the A1R [54].

Despite the apparent potential of A2BRs to engage functional selectivity through activation of different classes of G proteins, interactions with β-arrestins or allosteric modulation at intracellular and extracellular sites, no ligands have been reported that selectively employ these pathways.

A3 adenosine receptors

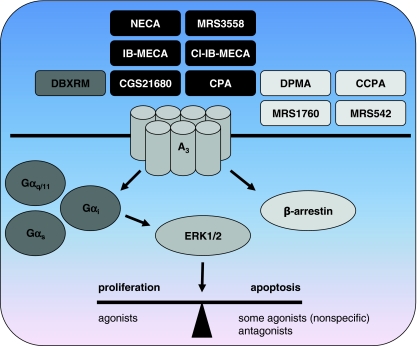

A3Rs couple primarily to proteins of the Gαi class (Gαi2 and Gαi3) and to a lesser extent to Gαq/11 [106]. Signaling by A3Rs in A6 renal epithelial cells is PTX insensitive and was suggested to be mediated by Gαs proteins [107] (Fig. 5).

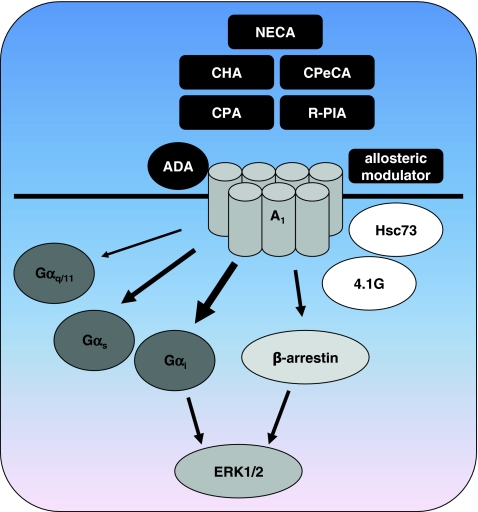

Fig. 5.

Functional selectivity of the adenosine A 3 receptor. Ligands with a bias towards β-arrestin-mediated signaling versus a Gα i-dependent pathway have been identified. Ligands that are antagonists for Gα i-mediated cAMP inhibition such as DMPA, CCPA, MRS1760, and MRS542 act as partial agonists for β-arrestin translocation. Interestingly, amongst the compounds that act as full agonists for both pathways, i.e., NECA, MRS3558, IB-MECA, Cl-IB-MECA, CGS21680, and CPA, both the nonspecific agonist NECA and the A3R-specific agonist MRS3558 show faster β-arestin translocation rates. DBXRM, a full agonist for the Gα i pathway, was a partial agonist for β-arrestin signaling. Besides these evident examples of functional selectivity, there are conflicting reports of the effects A3R ligands have on apoptosis and proliferation. Since in many of these studies very high ligand concentrations were used, care must be taken when drawing conclusions about biased effects on cell growth. See references in the text for more detailed information

The A3R has been described as enigmatic, in the sense that many of the effects ascribed to A3Rs are contradictory, such as neuroprotection vs. neurodegradation, cardioprotection vs. cardiotoxicity, anti-inflammatory vs. proinflammatory, immunosuppression vs. immunostimulation and pro- vs. anti-apoptotic effects [108]. In addition, there are quite some remarkable differences in expression, sequence homology and affinity of ligands between human and rodent A3Rs, complicating thorough characterization of these receptors.

The A3R contains a potential nuclear localization motif in its intracellular helix 8, suggesting that the receptor may interact with proteins involved in nuclear transport [109]. A3Rs on the nuclear membrane may be activated by intracellular adenosine and interact with nuclear G proteins or nuclear β-arrestin-1. Although nuclear expression of A3R has to be experimentally validated, signaling by intracellular receptors is a possible new area where functionally selective ligands may be of use [110].

Biphasic effects at high agonist concentrations

The effects of A3R-specific agonists such as IB-MECA 21 and Cl-IB-MECA 22 on proliferation have been described as being biphasic, e.g., preventing apoptosis at low (1 μM) concentrations, and inducing apoptosis at very high (10–100 μM) concentrations [111, 112] (Fig. 5). Biphasic stimulation of ERK1/2 was also observed in the mouse N13 microglia cell line, where low concentrations of Cl-IB-MECA or NECA stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a PTX-sensitive manner, while higher concentrations (≥10 μM) were without effect [113]. Also, Cl-IB-MECA inhibited proliferation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in A375 human melanoma cells at high (10 μM) concentrations [114]. Such a biphasic effect was not observed when A3R-transfected CHO cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of NECA, which resulted in a sigmoidal increase in ERK1/2 activation [27, 115]. It is therefore unclear if the observed biphasic signals should be contributed to the stimulation of another pathway by A3Rs at higher agonist concentrations, to rapid desensitization of the receptor at higher agonist concentrations, non-selective activation of other adenosine receptors or other pathways, or a combination of the above.

There however is evidence that the effects of high concentrations of certain A3R agonists are A3R independent. For instance, in the human papillary thyroid carcinoma NPA cell line the agonist Cl-IB-MECA inhibited cell growth at high concentrations with an IC50 of 38 μM [116]. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was rapidly reduced by 40 μM Cl-IB-MECA and this effect was not blocked after preincubation with the antagonists MRS1523 23 (10 μM) or FA385 24 (5 μM). Similar anti-proliferative effects of high concentrations of Cl-IB-MECA (30 μM) were reported in human leukemic cell lines HL-60 and MOLT-4 in the presence of the antagonists MRS1523 23 (10 μM) or MRS1220 25 (5 μM) [117]. An A3R agonist that is structurally related to Cl-IB-MECA, the ring-constrained N-methanocarba nucleoside MRS1898 26 [118], did not induce apoptosis at high micromolar concentrations [117]. In addition, IB-MECA (100 μM) suppressed proliferation in a variety of human breast cancer cells which do not have detectable levels of A3R mRNA, while incubation with Cl-IB-MECA (100 μM) killed the cells [119]. Adenosine 1 and several adenosine analogs such as 3′dA (Cordycepin) 2, 2CdA (Cladribine) 3, and CADO 4 also inhibited growth of human breast cancer cells [119]. These findings suggest that the anti-proliferative effects of high concentrations of certain A3R agonists such as IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA are A3R-independent and may be specific to a certain class of A3R agonists and/or cancer cells. Therefore, these biphasic effects are likely not indicative of biased signaling at higher concentrations of agonists.

Antagonist-mediated effects

Surprisingly, incubation of human HL-60 leukemia or U-937 lymphoma cell lines with relatively low concentrations of the antagonists MRS 1191 28 (0.5 μM), L-249313 29 (0.5 μM) or MRS 1220 25 (10 nM) resulted in reduced cell growth and apoptosis, which were reversed by addition of low concentrations of agonists [120]. A more recent study showed anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of an antagonist at high concentrations (30–50 μM) in T24 human bladder cancer cells [121]. This truncated analog of Cl-IB-MECA, named truncated thio-Cl-IB-MECA 30, induced cell cycle arrest and regulation of several cell cycle and apoptosis related proteins, ERK1/2 and JNK at 50 μM. With the use of pharmacological inhibitors a role for ERK1/2 and JNK in A3R-antagonist induced apoptosis was implicated [121]. The fact that antagonists induced apoptosis suggests that there is a basal tone of the receptor, either because of constitutive activity or endogenous adenosine. This observation may also be an indication of functional selectivity, where the “antagonists” activate other pathways than the prototypical agonists. The latter option however is less likely because three antagonists (MRS1220 25, MRS1191 28, and L-249313 29) of different chemical classes showed the apoptotic effect in the same study [120].

Functional selectivity of A3 adenosine receptors

Clear evidence for functional selectivity of A3R ligands at the human receptor was provided by Gao et al. [122]. This group compared ligand-induced efficacy of PTX-insensitive β-arrestin translocation with previously reported efficacies for the Gαi-mediated inhibition of cAMP. They used CHO PathHunterTM cells that express a modified A3R with a C-terminally fused enzyme fragment and β-arrestin fused to an N-terminal deletion mutant of β-galactosidase. Upon stimulation of the A3R the engineered β-arrestin interacts with the enzyme fragment linked to the A3R, resulting in the formation of a functional β-galactosidase enzyme that converts a substrate into a detectable signal. Most of the tested compounds that were full agonists at the Gαi pathway such as CPA 5, NECA 8, CGS21680 17, IB-MECA 21, Cl-IB-MECA 22, and MRS3558 27 acted as full agonists in the β-arrestin assay as well (Fig. 5). The rates of A3R translocation induced by NECA 8 and MRS3558 27 were higher than those of IB-MECA 21 and Cl-IB-MECA 22, whilst the efficacy for β-arrestin translocation of all these compounds was 100%. In addition to the rate of β-arrestin translocation, the efficacy of NECA 8 for Ca2+ mobilization was also higher than that of Cl-IB-MECA 22, indicating substantial differences in the mode of action of these ligands.

Most interestingly, several compounds that acted as antagonists in the cAMP assay amongst which DPMA 31, CCPA 32, MRS1760 33, and MRS542 34 were partial agonists for β-arrestin recruitment (Fig. 5). This is a clear indication that these ligands are functionally selective at the A3R. The opposite, i.e., full agonism for β-arrestin versus partial agonism or antagonism for the Gαi-mediated pathway, was not observed for any of the compounds tested.

Activation of ERK1/2 by the A3R in the CHO PathHunterTM cells was completely Gi-mediated, as was previously shown for A3R-mediated responses in CHO cells [123]. This indicates that β-arrestin-mediated signaling is not involved in ERK1/2 activation in CHO cells. DBXRM 35, which was a full agonist for the Gαi-mediated pathway, behaved as a partial agonist for β-arrestin recruitment, another indication of engagement of functionally selective pathways by A3R ligands. In order to determine if the difference in efficacy of DBXRM has functional consequences, CHO PathhunterTM cells were desensitized for 24 h with DBXRM 35 (full agonist for Gαi and a partial agonist for β-arrestin) or with IB-MECA 21 (full agonist at both pathways) and ERK1/2 activation by the full agonist MRS3558 27 was determined. Cells incubated with DBXRM 35 showed higher ERK1/2 activation (less desensitization) than cells desensitized with IB-MECA 21, indicating that activation of the β-arrestin pathway is involved in A3R desensitization in these cells.

The rat A3R was shown to redistribute a GFP-tagged version of β-arrestin-2 to small punctuate spots located both near the plasma membrane and within the cytoplasm after stimulation with R-PIA in CHO cells [40]. However, there was no significant overlap of β-arrestin-2 and the rat A3R. In contrast to these findings, when rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells, which express high levels of the rat A3R, were stimulated with NECA no changes in the distribution of β-arrestin-1 or β-arrestin-2 were observed [124].

It is noteworthy that the internalization rate of rat A3Rs was found to be dependent on cysteine residues C302 and C305 downstream of helix 8 in the carboxyl terminus of the receptor that are thought to anchor the carboxyl terminus to the membrane through palmitoylation [40]. When these cysteines were mutated to alanines that cannot undergo palmitoylation, the rat A3R underwent more rapid internalization upon stimulation with R-PIA. The same study also showed that internalization is critically dependent on three C-terminal GRK phosphorylation sites. Moreover, mutation of the cysteine residues to alanine resulted in a basal phosporylation of the rat A3R [125]. Since receptor phosphorylation, β-arrestin recruitment, and internalization usually are highly dependent upon each other, one could speculate that the faster rates of β-arrestin translocation induced by NECA and MRS3558 compared to IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA [122] reflect different conformations of the C-terminus of the receptor induced by these compounds, which allow faster phosphorylation and/or interaction with β-arrestin. Another possibility is that these functionally selective agonists differentially promote palmitate removal, resulting in a receptor that is more susceptible to phosphorylation and interaction with β-arrestins.

Conclusion and perspectives

Functional selectivity of synthetic ligands has been convincingly shown for the A1R and A3R. In case of the A1R, ligands induced differential coupling to G proteins, whereas A3R ligands can selectively activate either G protein or β-arrestin pathways. All adenosine receptors have been shown to interact with proteins additional to G proteins such as β-arrestins or other scaffold proteins. Since binding of cytosolic scaffold proteins to the intracellular domains of 7TMRs is expected to induce distinct conformations that theoretically can lead to a functionally selective response via these adapter proteins, it is remarkable that biased signaling through scaffold proteins has not been observed to date for adenosine receptors. Especially, the A2AR binds a wide variety of scaffold proteins and would be expected to be able to mediate a functionally selective response through these proteins. However, many of the studies described in this review that investigated G protein-independent signal transduction used only the classical subtype-selective agonists, or promiscuous ligands such as NECA. This is particularly true for studies investigating novel pathways such as those mediated by scaffold proteins. The assays deployed to study alternative G protein-independent pathways are often tedious and not readily suitable for the screening of compound libraries. This may have contributed to the lack of data describing functional selectivity mediated by scaffold proteins. Although there are several examples where stimulation with an agonist enhances the interaction of a given GPCR with a scaffold protein other than β-arrestin [7], to our knowledge there are no cases where this leads to a truly biased response. This makes one wonder if the theoretical mechanism of biased responses through scaffolding proteins other than β-arrestins is physiologically relevant, or is just overlooked because it has not been tested so far.

Functional selectivity is a relatively new phenomenon, due to the fact that the experimental techniques needed to distinguish between signal transduction pathways became only recently available. In classical organ bath experiments where contraction of a tissue is used as final and integrated readout of agonistic signaling, differential signaling between G protein and β-arrestin went unnoticed. Only with the use of sensitive cellular assays and molecular biology it became possible to study the individual signal transduction pathways that may lead to a final response such as contraction of a tissue. Surprisingly, the new method of choice to identify novel biased ligands may be a technique that relies on studying an integrated response after all, instead of individual pathways. In this case, the readout is a change in cellular morphology upon 7TMR-mediated signaling, caused by rearrangements of the cytoskeleton. The altered morphology can be detected using label-free techniques such as variation in cellular impedance [126]. Label-free techniques nowadays are sensitive enough to distinguish between G protein families and eliminate the need to perform multiple assays in order to detect divergent signaling pathways.