Abstract

Arterio-venous (A-V) malformations of the ear are uncommon lesions. While most are secondary to trauma, spontaneous lesions are very rare. A-V malformations anywhere in the body can have a range of clinical effects from mild disfigurement to cardiac failure. Treatment of these lesions poses a challenge to the surgeon due to their extreme vascularity and high incidence of recurrence. Highly selective arterial embolization and surgical resection offer the best chance for cure. In this article, the authors present a case of acquired A-V malformation of the ear, which was treated successfully by surgical excision without pre-operative embolization with no recurrence on follow-up proving that in areas of easy and superficial access, a pre-operative embolization need not be routinely carried out in cases of small to medium sized vascular tumors.

Keywords: Ear, Arterio-venous (A-V) malformation, Surgical excision, Angiography

Introduction

Arterio-venous (A-V) malformations are a group of conditions, which can have a range of effects on the patient ranging from disfigurement to life-threatening morbidity. A-V malformation of the head and neck are quite rare in contrast to low-flow vascular anomalies, but often present with significant haemorrhage or cosmetic defects. Treatment of these high-flow vascular anomalies with multiple, low resistance shunts which short-circuit the capillary bed is hazardous and has a predictably high incidence of recurrence if not managed correctly. Intervention is indicated for complications such as pain, haemorrhage, pressure symptoms, ischaemic ulceration and even congestive cardiac failure. After Farmer et al. [1], perhaps first reported congenital arteriovenous fistula of the ear in 1956, less than 10 reports dealing with this entity have been published till date and it still remains a rare entity. We present a rare case of a congenital A-V malformation arising from the ear that was successfully treated by surgical excision.

Case Report

A 45-year-old male patient with macrotia and swelling of the posterior auricular region of the right ear presented to the outpatient Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, and it gradually increased in size, especially so in the past two to 3 years to attain the present size. Past history was unremarkable except for a history of appendicetomy done 8 years earlier. On examination, vital signs were normal. There was no pallor. Ear examination revealed macrotia (Fig. 1) along with a 2 × 2 cm, painless, pulsatile and compressible bilobed swelling behind the lobule of the right pinna (Fig. 2). The mass had well-defined, circumscribed margins. Palpation revealed local rise of temperature. There was no discoloration of the overlying skin, tenderness or itching. There was no evidence of cartilage or skin involvement, localized lymphadenopathy or dilated veins over the swelling. Pre-therapeutic workup revealed a normal haemogram and the remaining laboratory investigations including coagulation profile, ECG and chest X-ray were within normal limits. An External Carotid Angiogram (ECA) was performed via a transfemoral route. A diagnosis of an A-V malformation with feeding vessels being posterior auricular artery and posterior auricular veins was made (post-auricular artery aneurysm). The patient was taken up for surgery; and a Wilde’s post-aural incision was made behind the right ear extending upto the angle of the mandible to expose the post-auricular behind the ear and the proximal tortuous posterior auricular artery and vein were identified and ligated (Fig. 3). The mass was then excised after identifying the distal end of the vessels and ligating them. Hemostasis was achieved. The specimen consisting of the auricular artery & vein (Fig. 4) was sent for histopathogical examination (HPE). Suction drain was placed and the skin was sutured in two layers, followed by dressing. The post-operative period was uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Macrotia

Fig. 2.

2 × 2 cm, painless, pulsatile and compressible bilobed swelling behind the lobule of the right pinna

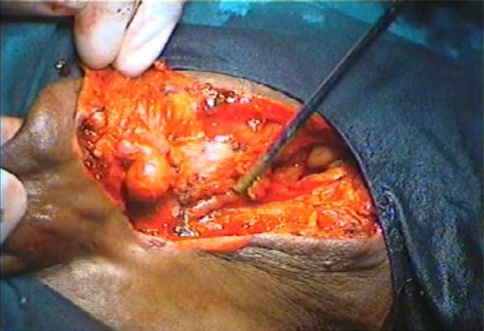

Fig. 3.

Proximal tortuous posterior auricular artery and vein were identified

Fig. 4.

Specimen consisting of the posterior auricular artery and vein

On gross HPE, pale brown to dark brown irregular nodular tissue bits were appreciated. Cut surface of the nodule was brown with central hemorrhage. After staining with Haemotoxylin & Eosin stain, histologically, sections show numerous markedly thick walled vessels with eccentric intimal proliferation and whorled thickening in the media & intima. The specimen also showed salivary gland and lymph node. The histopathological features were suggestive of arterialisation of veins due to A-V malformation and were consistent with the clinical diagnosis. The patient is on regular follow up and is free of the disease for the last 2 years (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

Post-operatively after 2 years

Fig. 6.

Post-operatively after 2 years

Discussion

The first use of the term “aneurysm by anastomosis” to describe a congenital arteriovenous malformation is attributed to the father of vascular surgery, John Bell, in 1815 [2]. A-V malformations consist of communications between arteries and veins via pathologically dilated capillary like vessels without the interposition of arterioles. Vascular malformations do not demonstrate cellular hyperplasia but display progressive ectasia of abnormal vessels, lined by 20 flat endothelium on a thin basal lamina. As a result, collateral formation is promoted, which in turn acts to divert regional blood flow from the periphery. The feeding arteries are dilated, lengthened, tortuous, and have thin walls that have undergone fibrous degeneration. A capillary bed is always present in contrast to a traumatically induced A-V fistula and constitutes the bulk of the vascular bed. The draining veins are enlarged and have a prominent muscular coat developed in response to the increased intraluminal pressure [3].

A-V aneurysms or malformations can be either congenital or cause by trauma (acquired). Those due to trauma are usually single fistular channels, resulting from an injury to an artery and an adjacent vein [4]. Typically, the vascular malformations are developmental anomalies that are present at birth and grow commensurately with the child. They often are not clinically apparent until the second or third decade of life, when they increase in size by dilation and collateralization. These changes are thought to be associated with puberty or pregnancy. In our case, the patient first noticed the swelling in the second decade of his life. Vascular malformations exhibit a normal endothelial cell cycle throughout their natural history [3, 5, 6].

Congenital fistulae that are present since births are extremely uncommon. They represent an arrest of the embryological developmental process. They always contain a number of abnormal A-V connections but seldom produce dramatic cardiovascular consequences. The majorities of congenital A-V fistulae develop in the limbs but may also occur in any organ of the body. They are most often asymptomatic and even when symptomatic, are well tolerated. Indication for treatment is disfigurement or bleeding. Acquired A-V malformations, mostly traumatic, are far more prevalent. They usually involve a single vessel when caused by trauma but in congenital form, they involve multiple vessels. In a series by Kohout et al. [7], reporting 81 A-V malformations located in head and neck area, 16% were in the ear, making it the second most common site for extracranial A-V malformation in the head & neck, second only to the cheek (31%).

When a vascular mass has a palpable thrill and a continuous bruit, it is always associated with abnormal A-V connection. An increase in temperature over the lesion is a striking feature. There may be bleeding and ulceration due to secondary chronic venous insufficiency. While in most instances, the diagnosis of congenital A-V fistula can be made on the basis of a clinical examination; the importance of angiography in delineating the precise nature and extent of the disease cannot be overemphasized. Auscultation by Doppler ultrasound will produce vivid documentation of the systolic and diastolic component of the fistula.

The definitive technique for diagnosis of an A-V malformation is superselective angiography with computer-generated digital subtraction of the overlying bony shadows. Today, superselective angiography combined with percutaneous trans-catheter intra-arterial vascular (selective) embolization with Gelfoam or Polyvinyl alchohol and if necessary, surgical (ablation) excision and reconstruction under hypotensive anesthesia is considered the mainstay of treatment. The goal of preoperative embolisation is primarily to diminish blood loss and to facilitate surgical extirpation. In our case, we deemed it avoidable to embolize the posterior auricular artery, as the artery was easily accessible for ligation near the field of excision and a complete excision was possible. Hence, intra-operatively we took care to correctly identify the artery by an extended post-aural incision up to the angle of the mandible and ligated it with the vein. Our experience proves that small to medium sized vascular tumors with easy access to the feeding vessels can be operated upon without pre-operative embolization. Other methods such as external carotid ligation, injections of sclerosants or radiotherapy are ineffective. Although amputation effectively controlled A-V malformation in 80 percent of the patients, recurrence or re-expansion is always a concern. Typically, a residual, incompletely resected A-V malformation re-expands 1–2 years after operation but may remain quiescent for decades proving the disease has no cure [8]. Complications of an A-V malformation include spontaneous rupture or traumatic violation, which may result in severe hemorrhage or rarely exsanguinations.

Conclusion

Large vascular tumors can be challenging and difficult to resect because of their location, proximity to vital structures and abundant blood flow. Congenital malformations are uncommon and their management has proved to be difficult for most surgeons. Pre-operative embolization and surgical excision offers the best method of treatment of these lesions. In our case, we deemed it avoidable to embolize the posterior auricular artery, as the tumor–vessel complex was easily accessible for ligation near the field of excision and a complete excision was possible. In areas of easy and superficial access, a pre-operative embolization need not be routinely carried out in cases of small to medium sized vascular tumors.

References

- 1.Farmer AW, Cloutier AM. Congenital arteriovenous fistula of the ear. Can Med Assoc J. 1956;75(1):36–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson JM. Carotid-cavernous sinus fistula accompanying facial trauma. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1977;14:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(77)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. Mast cells in hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Pediatrics. 1982;70:48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orbach S. Congenital arteriovenous malformations of the face. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1976;42:2–13. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batsakis JG, Rice DH. The pathology of head and neck tumors: vasoformative tumors. Head Neck Surg. 1988;3:231. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyldesley WR, Littfewood AHM. Haemangioma of the maxilla: a case report. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1975;13:55. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(75)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohout MP, Hansen M, Pribaz JJ, Mulliken JB. Arteriovenous malformations of the head and neck: natural history and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:643–654. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.June K, Wu, et al. Auricular arteriovenous malformation: evaluation, management, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:985. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000154207.87313.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]