Abstract

The Facial Nerve Schwannoma is a rare tumor and it seldom involved the middle cranial fossa. Facial nerve schwannoma has various manifestations, including facial palsy but unfortunately facial nerve is very resistant to compression and often facial nerve paralysis or a facial weakness are not present. We present a case of giant facial nerve schwannoma involved the middle cranial fossa without facial nerve paralysis. In these cases the unilateral hearing loss (if present) guide to a correct diagnosis.

Keywords: Middle cranial fossa, Facial nerve, Facial nerve paralysis, Diagnosis

Introduction

Facial Nerve Schwannomas (FNS) are rare slow growing lesions that can involve any nerve segment. The majority of FNS are intratemporal, with 9% of cases arising from the intraparotid portion. Multiple-segment tumors are more common (63.6%) than single-segment tumors (36.4%) [1]. This emphasizes the need for evaluation of the entire length of the nerve; in fact, any segment may be involved, either singly, or in conjunction with its contiguous neighbors. The most frequently involved segments are the labyrinthine and the geniculate ganglion [1]. Their extention into the Middle Cranial Fossa (MCF) is uncommon.

Facial nerve schwannoma has various manifestations, including facial palsy, hearing loss, vestibular weakness, a palpable parotid mass, and even no symptom depending on its size and site [2, 3]. Unfortunately facial nerve is very resistant to compression and often facial nerve paralysis or a facial weakness are not present, for this a normal facial nerve function occur in 27.3% of all patients with facial nerve schwannomas [4].

Case Report

We report a case of a 60-year-old man came to our attention for unilateral hearing loss. Clinical examination was normal and facial nerve palsy, facial nerve weakness or facial parasthesiae were not present. Romberg test was negative and Unterberger stepping test showed minimal deviation to the left. Clinically cerebellar signs were absent. Audiological assessment revealed a left Neuro-Sensorial Hearing Loss (NSHL) (PTA was 55 dB) and Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) showed in left ear a pathologic answer.

ABR examination revealed an increase in absolute wave V latency and I–V interpeak latency (≥4.4 ms). This finding suggested a not exclusive labyrinthine pathology.

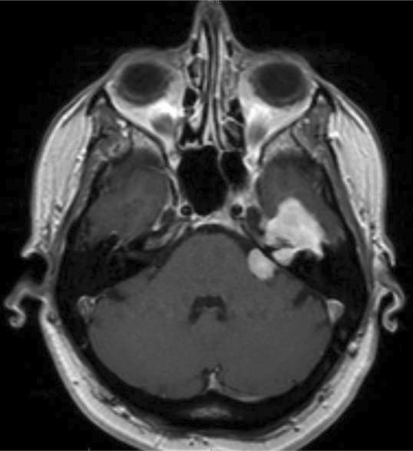

Preoperative MRI scans showed an enhancing CerebelloPontine Angle (CPA) giant tumor with considerable Middle Cranial Fossa and internal auditory canal invasion that appeared enlarged (Fig. 1). The mass involved the left temporal cerebral lobe and the geniculate ganglion (Fig. 1). The CT images showed apical temporal bone erosion with involvement of geniculate ganglion area and tegmen tympani interruption (Fig. 2). Compression of the facial nerve and the acoustic nerve was relieved by destruction of the facial and auditory canals in the petrous bone.

Fig. 1.

MRI scans showed an enhancing cerebellopontine angle tumor with considerable internal auditory canal and middle cranial fossa invasion

Fig. 2.

The CT images showed apical temporal bone erosion with involvement of geniculate ganglion area and tegmen tympani erosion interruption

The patient underwent to modified trans-cochlear (TC) approach for total removal the FNS and immediate sural nerve grafting to reconstruction.

After the surgery our patient had facial nerve paralysis House-Brackmann Grade VI recovered to Grade III after 1 year.

Discussion and Conclusion

Because of the long complex course of the facial nerve, FNSs can originate in any segment of the nerve, from the glial-Schwann cell junction at the cerebellopontine angle to the peripheral branches in the face. Though most schwannomas usually originate in the labyrinthine and tympanic segments above the oval window [5], schwannomas can originate in any other portion of the nerve, such as the internal auditory canal (IAC) or extratemporal area [6].

There are no specific symptoms for FNSs, and diagnosis may be difficult.

In the series conducted by Schaitkin and May, it was noted that diagnosis of a tumor could take place even 18 years after the initial onset of symptoms [7].

Symptoms may be different depending on the involved segments. When a FNS is present in the CPA or IAC segments, NSHL and tinnitus are frequently observed. Patients with Schwannomas arising in the labyrinthine segment tend to present with slowly progressive facial paresis and NSHL. Patients with tumors of the tympanic segment commonly present with progressive facial paresis, fullness in the ear, and Conductive Hearing Loss (CHL). If an FNS is present in the vertical segment, patients show progressive facial paresis, otorrhea, and CHL. Patients with tumors arising in the peripheral segment, frequently show a mass in the parotid gland. This may be accompanied by slowly progressing facial paresis [8].

So, Facial nerve paralysis is not always present and it is not the most important symptom and however the severity of symptoms is not directly related to tumor size.

Still a giant FNS without facial paralysis is extremely rare.

The reasons for non manifestation of facial nerve paralysis may be neuronal tolerance induced by the extremely slow growth of the tumor; furthermore in extremely slow growth tumors, as showed by Sunderland, about 90% of nerve fibres have to be damaged to evidence a facial nerve paralysis [9]. Besides abundant tumor blood flow also supporting the facial nerve, thus maintaining nerve function [4].

Moreover the tumor location at the horizontal portion, between the internal auditory canal and the geniculate ganglion, where many dehiscences in the surrounding petrous bone could easily protect the facial nerve from the compression force of the tumor [4].

Our case shows that is very important focused the attention to unilateral sensorineural (or conductive) hearing loss, it is sometimes the only manifestation of cerebello-pontine angle tumors like our facial nerve schwannoma.

Today, precise preoperative anatomical localization with both imaging modalities is the expected norm in patients with FNS. Some of the basic imaging characteristics of any neuroma can be applied, thus differentiating this lesion from other facial nerve neoplasms: Magnetic resonance imaging shows a mass that is midly hypointense or isointense relative to brain on non-contrasted T1-weighted images and is enhanced following gadolinium administration [10, 11]. Heterogeneity or cystic change, well appreciated on T2-weighted images, may also be seen. Bone-algorithm CT shows a mass expanding or remodelling its bony surrounds rather than aggressively destroying its margins. Surgical management is influenced by three factors such as the site of tumor, the extent of lesion, the hearing status [11].

In our case we selected a TC approach, because this surgical technique allows to remove big size FNS when the hearing preservation is not likely [11]. If the cochlear function in the tumor ear is poor and the contralateral ear shows a normal hearing, a translabyrinthine (TL) or transcochlear approach are the best choices. The TC approach is the only one that allow the management of any sized and intracranially located facial nerve tumors [11]. The TL permit the treatment of FNSs located in Internal Auditory Canal and Cerebello-pontine angle [12], in our patient extension of tumor required a wide exposure of the nerve in order to complete removal and reconstruction. Facial nerve schwannomas can present in various ways and a normal facial nerve function may not related to the tumor size. As the present case the unilateral Hearing Loss can be the only one symptom. Preoperative imaging is mandatory to plan the correct approach and the nerve reconstruction.

References

- 1.Kertesz TR, Shelton C, Wiggins RH, Salzman KL, Glastombury CM, Harnsberger R. Intratemporal Facial Nerve Neuroma: Anatomical Location and Radiological Features. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200107000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chun YM, Park K, Lee JS, Chun SH. The management of facial nerve schwannoma. Kor J Otolaryngol. 1997;40:1052–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim CS, Sung MH, Hwang EG, Chung HW, Han MH. Surgical management of intratemporal facial nerve neurilemmoma. Kor J Otolaryngol. 1989;32:391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furuta S, Hatakeyama T, Zenke K, Nagato S. Huge facial schwannoma extending into the middle cranial fossa and cerebellopontine angle without facial nerve palsy—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2000;40:528–531. doi: 10.2176/nmc.40.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman JD, Dagnew E, Pensak ML, Loveren HR, Tew JM. Facial nerve neuromas: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg. 2002;50:450–456. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulec JL. Facial nerve neuroma. Ear Nose Throat J. 1994;73:721–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaitkin B, May M, editors. Tumors involving facial nerve. New York: Thieme; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherman JD, Dagnew E, Pensak ML, et al. Facial nerve neuromas: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:450–456. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunderland S (1977) Some anatomical and pathophysiological data relevant to facial nerve injury and repair. In: Fisch U (ed) Facial nerve surgery. Kugler/Aesculapius, Birmingham, pp 448–456

- 10.O’Donoghue GM, Brackmann DE, House JW, Jackler RK. Neuromas of the facial nerve. Am J Otolaryngol. 1989;10:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanna M. The facial nerve in temporal bone and lateral skull base microsurgery. Stuttgard: Thieme; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okabe Y, Nagayama I, Takiguchi T, Furukawa M. Intrapetrosal facial nerve neurinoma without facial paralysis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1992;19:223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]