Abstract

Background

Malar mounds may be accentuated by chronic lid edema, with the development from malar edema to malar mounds and finally to malar festoons. Because standard techniques do not seem effective and not specifically proposed for the treatment of malar festoons, subperiosteal vertical upper-midface lift associated with lower blepharoplasty overcomes these shortcomings.

Methods

Twelve patients (3 males and 9 females, age = 47 ± 6 years) underwent video-assisted endoscopic subperiosteal vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) in conjunction with a lower blepharoplasty between 2006 and 2007 for treatment of malar festoons. This includes simultaneous lower blepharoplasties and video-assisted transtemporal subperiosteal and sub-SMAS tissue release.

Results

All patients healed uneventfully without any major postoperative problems. The surgical outcome was evaluated according to the analysis of photographs obtained before and after surgery and the analysis of pre- and postoperative measurements. The technique we used (SUM-lift) achieved a significant rejuvenation of the midface and the malar festoons.

Conclusion

Subperiosteal vertical midface lift resuspends and redrapes the facial network that originates at the level of the orbital rim. It seems to improve the permeability characteristics of the malar septum in the treatment of malar festoons and malar mounds by freeing the cheek tissue from underlying bone and redraping the malar septum. It is a reliable technique to improve malar mounds, palpebral bags, or festoons.

Keywords: Festoons, Malar membrane, Vertical subperiosteal midface lift, Malar mounds, Blepharoplasty

Introduction

During the aging process three variations of the infraorbital area may appear. Malar mounds, palpebral bags, or festoons (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 17a). Festoons are developmental attenuation of the orbicularis oculi muscle with laxity of the attachments between the orbicularis and the deep fascia [1]. The orbicularis oculi muscle progressively sags until folds of muscle are suspended across the lower lid. Malar mounds in contrast are discrete soft tissue convexities that bulge directly outward from the malar prominence [2, 3]. They retain a relatively stable shape during usual facial movements, but can be worsened with smiling. Palpebral bags or baggy eyelids develop at an early age and are also known as herniated intraorbital fat [1]. They are the result of intraorbital fat bulging outward against an attenuated or weak orbital septum of the upper or lower eyelid. Some of these changes cause functional and aesthetic problems for which surgical correction is a gratifying procedure, although surgical treatment of festoons, mostly seen in older patients who have lax supporting structures [1] in the preseptal area, orbital area, and the jugal region of the lower lid, is known to be difficult [1–5].

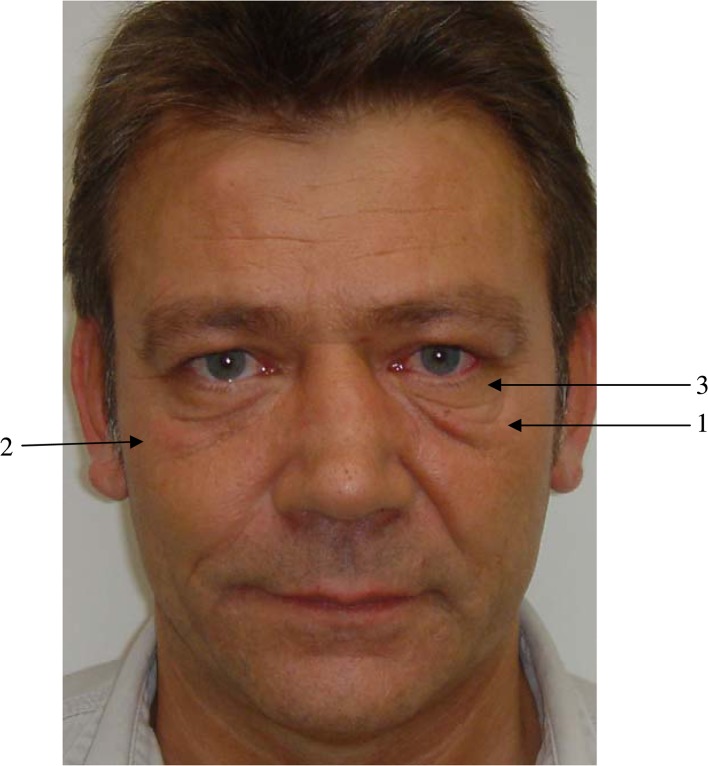

Fig. 1.

1 = Festoons ; 2 = malar mounds; 3 = palpebral bags

Fig. 17.

a Preoperative view of a 48-year-old patient with marked malar festoons, redundant eyelid skin, and deep nasojugal grooves. b Postoperative view (14 months) after he underwent a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift); the malar festoons are improved

Various surgical techniques have been used to treat malar bags and muscle festoons for the lower eyelid, taking into account its various etiologies. Pessa and Garza [2], who analyzed malar mounds and malar edema, found that the malar septum acts as a relatively impermeable barrier that allows tissue edema to accumulate above its cutaneous insertion. Following their studies, this septum defines the lower “boundary” of several clinical entities, e.g., malar mounds, malar edema, malar festoons. Therefore, malar mounds may be accentuated by chronic lid edema which may imply a time course in the progressive development from malar edema to malar mound and at least to malar festoons [2].

Knowing that standard lower blepharoplasties cannot correct malar loops with muscle pouches, nor the sagging of the lower orbicular muscles (ptosis), and that standard techniques do not seem effective and are not specifically proposed for the treatment of malar festoons, subperiosteal vertical upper-midface lift associated with lower blepharoplasty overcomes these shortcomings. In this article we share our experiences with our technique.

Method

Indications

Video-assisted endoscopic subperiosteal vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) in conjunction with a lower blepharoplasty and/or endoscopy-assisted forehead plasty, if needed, is indicated in patients with moderate skin elasticity and festoons which cannot be treated by high SMAS rotation advancement surgery alone and in patients who already have undergone a traditional face-lift procedure. Patients who exhibit a vertical descent of the midface (malar flatness, festoons, malar bags), including an oval configuration to the orbit, elongation of the lower eyelid skin, concomitant ptosis of the composite flap, including skin, muscle, and fat, prominent nasolabial fold, and early jowl formation, are ideal candidates for this procedure. Prior lower blepharoplasty patients who exhibit lid retraction and scleral show also may be improved by advancement of this upper-midface procedure [5–14].

Surgical Techniques

The procedures routinely have been performed under general anesthesia, with local anesthesia infiltration for homeostasis and perioperative intravenous antibiotics (Augmentin®, GlaxoSmithKline) for 48 h. No anticoagulation therapy was performed. Infiltration of the area was performed with a vasoconstricting solution consisting of 1 ml of 1:1000 epinephrine in 1000 ml of normal saline. Markings were performed preoperatively with the patient in a sitting position. If an upper blepharoplasty was needed, the eyebrow was held at the desired level. The redundant upper-eyelid skin was marked with the brow in an elevated position to avoid over resection. The center of the forehead at the region of the glabella was infiltrated, as were the corrugators and procerus muscles to obtain adequate vasoconstriction in the area to be dissected. The anterior temporal crest was infiltrated to produce hydrodissection and improve visualization. The infiltration continued laterally over the superior lateral orbital rim to the lateral canthus into the upper midface and the buccal sulcus.

For the forehead and upper-midface rejuvenation, six access incisions are used. The surgery is performed with a 4-mm, 30° down scope, with a protection sleeve and irrigation system to keep the field clean. The operation begins by elevating the forehead through two 2-cm sagittal incisions 1 cm behind the anterior scalp line and a standard subperiosteal forehead plasty is performed. The average lateral brow lift ranges between 4 and 6 mm as needed. For further correction of upper-eyelid pseudoptosis, loose skin of the upper lid in conjunction with a very small orbicularis oculi muscle fibers strip is resected. The protruding fat of the medial pocket is removed when needed.

Following the standard central forehead lift, the procedure proceeds to the lateral forehead and midface. The upper midface is elevated over the deep temporalis fascia (fascia temporalis profunda) in the scalp via a 3–4-cm transverse temporal incision 4 cm behind the anterior scalp in an open angle of about 120° toward the helical rim (Fig. 2). The incision is not parallel to the temporal hairline and is slightly perpendicular to the vector of repositioning. The lateral dissection extends over the deep temporalis fascia covering the temporalis muscle (sub-SMAS plane). This fascial layer is elevated with the forehead tissue by detaching it along the temporal crest by performing blunt dissection.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift). The temporal incision is marked. The incision is curved slightly forward

Next, from the temporal area over the deep temporalis fascia, the midface is approached sub-SMAS, dissecting subperiosteally inferior-lateral to the sentinel vein, between the sentinel vein and the zygomatic-temporal nerve (Fig. 3) (sensitive nerve), subperiosteally over the anterior surface of the zygomatic arch (the facial nerve is on top of the elevator, over the fascia temporalis parietale), and entering the midface under the orbicularis oculi muscle. The dissection on the malar area is done subperiosteally under the orbicularis oculi muscle, leaving the septum orbitalis, infraorbital rim, suborbital oculi fat (pad), and zygomatic major muscle on top on the periosteal elevator.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift). The endoscope is introduced under the temporal fascia into the upper midface. The scissor lies over the superficial temporal fascia and under the skin

The soft tissue of the cheek is freed from underlying bone through a buccal incision placed from the molar to the canine to leave an adequate cuff of gingiva for closure (Fig. 4). Subperiosteal dissection is performed on the maxilla and zygoma using a custom-made periosteal rasp. The dissection extends from the nasal spine to the lateral buttress of the maxilla. It frees the tissue around the pyriform aperture, over the frontal process of the maxilla, along the inferior and lateral orbital rim, around the infraorbital nerve, then vertically up to the frontal process of the zygoma to the level of the lateral canthus, and laterally over the zygoma body to the zygomatic arch (Fig. 5). Freeing is performed over the anterior two thirds of the zygomatic arch. Release of the arcus marginalis is especially important for correcting the tear-trough deformity and elevation of the lid-cheek interface, just as freeing from the nasal spine and pyriform aperture is important for elevation of the upper lip and corners of the mouth.

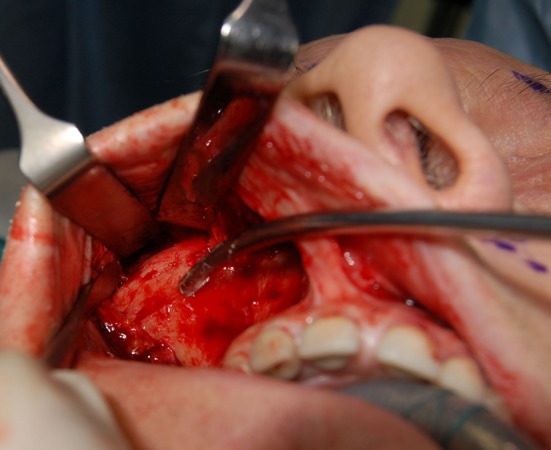

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift); enoral view after degloving the maxilla, the zygoma, and two thirds of the zygoma arch. The suction cannula points to the sensitive zygomatic nerve

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift). The soft tissue of the cheek is freed from underlying bone through a buccal incision using a custom-made periosteal rasp. The dissection extends from the nasal spine to the lateral buttress of the maxilla; it frees the tissue around the pyriform aperture, over the frontal process of the maxilla along the inferior and lateral orbital rim, around the infraorbital nerve, then vertically up to the frontal process of the zygoma to the level of the lateral canthus, and laterally over the zygoma body to the zygomatic arch

Once the soft tissue had been thoroughly freed, elevation of the midface begins by insertion of two 2 × 0 PDS sutures by an intraoral approach, taking a deep bite of the soft tissue (Fig. 6). The area for the cheek tissue suture fixation placement was marked previously; it is a cross in the medial cheek located at the intersection of a vertical line dropped from the lateral canthus and a transverse line directed from the lowest aspect of the alar groove at its intersection with the lip. The vector of suspension is determined entirely by the position of the key area relative to the point of bony zygomatic divergence. The patient’s head is turned to the side and a retractor is inserted through the short scalp incision into the temporal fossa. The patient’s head is straightened. The sutures are advanced up by suspending the cheek to the desired position until the identifying premolar show confirms adequate mobilization (Fig. 7a, b). The effects are assessed for symmetry and the sutures are fixed into the deep temporal fascia (Figs. 8 and 9). This superior vertical elevation lifts the deep tissues, which are maintained in the proper position of the fixed sutures. Most important is the production of a large soft tissue volumetric mass in the malar and submalar regions (Fig. 9). The distal end of the sutures with their multiple knots is trimmed and secured with a 4 × 0 Vicryl suture to lay flat in the temporal fossa, avoiding any discomfort of the sticky sutures.

Fig. 6.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift). The area for the cheek tissue fixation placement is marked. It presents as a cross in the medial cheek located at the intersection of a vertical line dropped from the lateral canthus and a transverse line directed from the lowest aspect of the alar groove at its intersection with the lip. The sutures have been placed into the soft tissue and the overlying periosteum. The ends of the sutures are gripped with an endo forceps exiting the temporal incision

Fig. 7.

a, b Intraoperative oblique view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift. The midfacial tissues are elevated until identifying premolars confirms adequate mobilization to the desired position by applying tension to the sutures exiting the temporal incision (a). This superior vertical elevation lifts the deep tissues, which are maintained in the proper position by anchoring the sutures in the deep temporal fascia in the desired position (b)

Fig. 8.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift. Superior vertical elevation produces a large soft tissue volumetric mass in the malar region. It is most important to assess large soft tissue volumetric mass production in the malar to achieve a natural and improved facial rejuvenation

Fig. 9.

Intraoperative view of a patient undergoing a vertical upper-midface lift. After mobilizing the midface tissues and the SMAS fascia, the mesotemporalis fascia is repositioned, suspended after suture fixation, suspending the midface tissue to the deep temporalis muscle fascia

In addition, the frontotemporal skin is lifted in a vertical direction and is also anchored to the temporal fascia. Several interrupted sutures are secured to the temporal fascia at the level of the access incision, allowing an open knotting technique and secure fixation of the flap (Fig. 9). After performing the midface elevation, a laterally based transposition orbicularis muscle flap, described by Hamra [15, 16], is used (Figs. 10 and 11); it is a safe and effective method to transmit a controlled amount of traction to the lower lid in lower blepharoplasty without the need for canthoplasty or canthopexy. The loose, redundant lower eyelid is meticulously removed without any muscle fibers. After meticulous homeostasis, the buccal sulcus is closed with interrupted sutures.

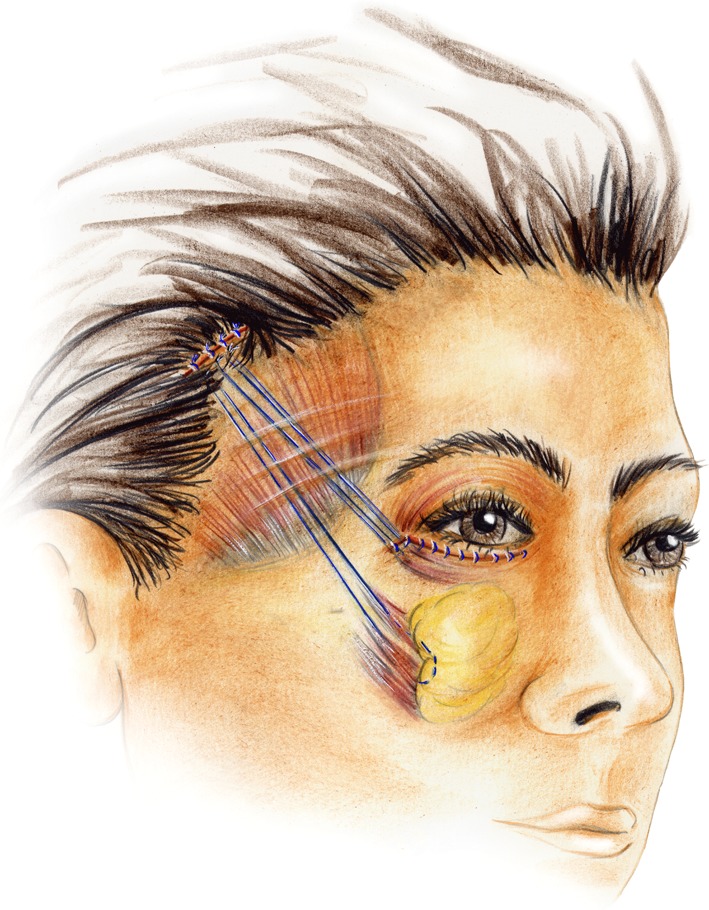

Fig. 10.

Illustration of the vertical upper-midface lift with the suspension sutures in place. Note the suspension of the soft tissue at the inferior lateral orbital rim area

Fig. 11.

Intraoperative view of the suspension sutures placed in the soft tissue at the inferior lateral orbital rim area after dissection of the orbicularis muscle for septal release and muscle suspension

Patients

Twelve patients (3 males and 9 females, age = 47 ± 6 years) underwent a SUM-lift between 2006 and 2007 for treatment of malar festoons. The procedure included simultaneous lower blepharoplasty and video-assisted transtemporal subperiosteal and sub-SMAS tissue release. All patients underwent a thorough, individualized preoperative evaluation to establish a correct diagnosis, evaluate asymmetries, estimate the degree of tissue repositioning, and decide on the level of fixation. In all patients, the distances of the marginal rim of the lower lid and the nasojugal grooves between defined points were measured preoperatively (Fig. 12a) and 6 and 12 months after surgery (Fig. 12b). Therefore, measurements were taken along a perpendicular line from the lateral limbus of the eye to a horizontal line of the oral commissure (Fig. 12a) to analyze the preoperative and postoperative positions of the most inferior point of the nasojugal groove (Fig. 12b).

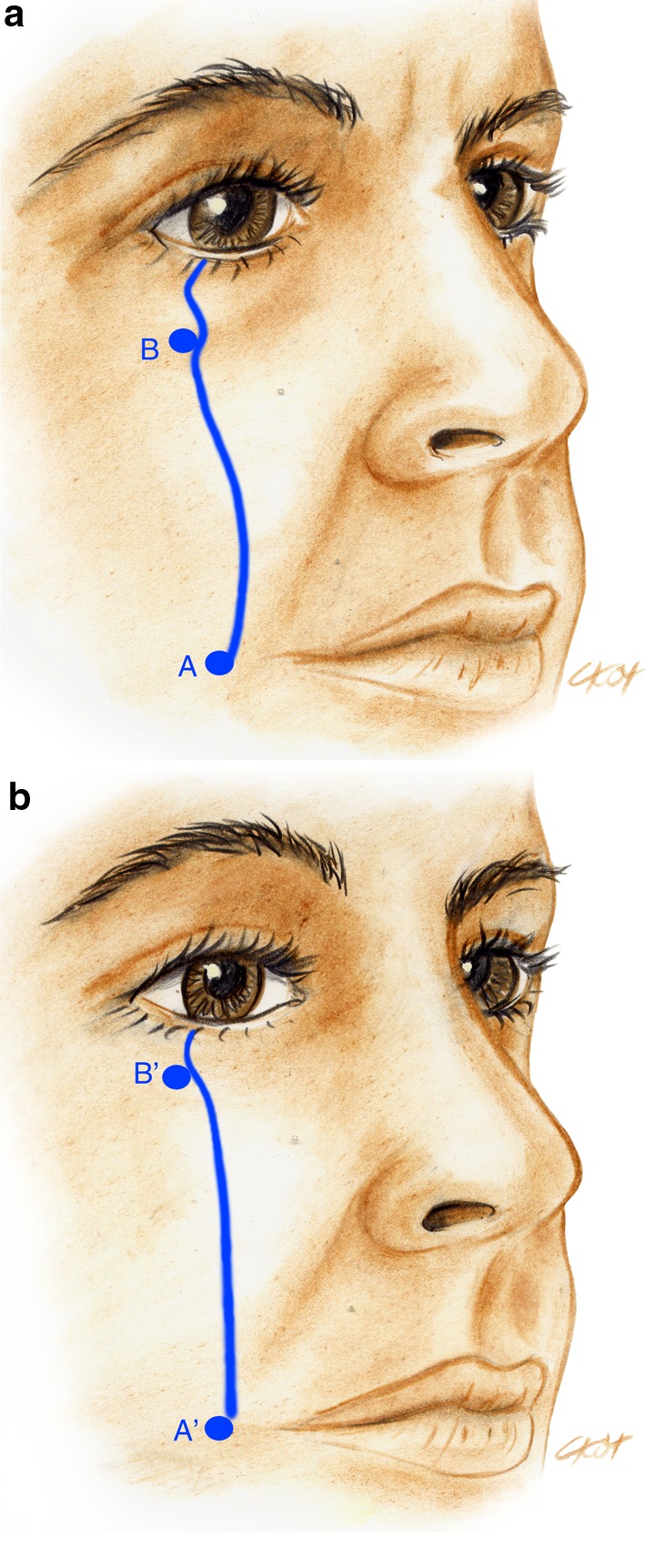

Fig. 12.

Schematic evaluating the position of the nasojugal groove. Measurements were taken along a perpendicular line from the lateral limbus of the eye to a horizontal line of the oral commissure (A) to analyze the preoperative position of the nasojugal groove (B). a Preoperative analysis. b Postoperative evaluation

Results

The median observation time was 12 months. The procedure on average took 2 h 40 min ± 25 min. Immediate healing was achieved without major complications, adverse reactions, or side effects. Edema remained for 10–12 days.

No alopecia was observed; no swelling or seromatous fluid collection necessitated a second procedure or prolonged drainage. Three patients showed a very small intraoral wound dehiscence of 3-5 mm, two on the left side and one on the right side. Using daily local irrigation, the wound healed by secondary intention after 7 days. All patients were judged to have satisfactory cheek elevation and enhanced contour without evidence of recurrent festoons, ptosis, or loss of fixation. The patients did not complain of pain in the treated area 3 days after surgery. They did not take painkillers for more than 2 days after surgery.

The surgical outcome was evaluated by analyzing photographs taken before and after surgery, and by analyzing pre- and postoperative measurements. Despite that 6 months after surgery drooping of the lateral brow position was observed at a mean of 2.3 mm, the technique we used achieved a significant rejuvenation of the midface and the malar festoons (Table 1). The examples seen in Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17 illustrate the indications and results.

Table 1.

Pre- and postoperative evaluation of the position of the nasojugal groove after a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) (N = 12)

| Preoperative | 6-month postoperative | 12-month postoperative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AB (cm) | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.3 |

AB distance between the oral commissure and the nasojugal groove position

Fig. 13.

a, c Preoperative views of a 54-year-old patient with ptosis of the malar tissues, hollowing of the infraorbital area and the cheek area, lengthening of the lower eyelid, attendant tear-trough deformity, and associated nasojugal grooves, nasolabial folds, and malar labial folds. b, d Postoperative views 12 months after a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift). Note the shortening of the vertical height of the lower eyelid, reduction of the nasojugal groove, and the enhancement of the eyelid-cheek junction to a more youthful position as well as the increased malar projection

Fig. 14.

a, c Preoperative views of a 48-year-old patient. He demonstrates ptosis of the malar tissues, loose festoons, hollowing of the infraorbital area, lengthening of the lower eyelid, attendant tear-trough deformity, and nasojugal grooves. b, d Six months after a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) the nasojugal groove is reduced, the length of the lower lid is shortened, the festoon is removed, and the eyelid-cheek junction is enhanced to a more youthful position with increased malar projection

Fig. 15.

a Preoperative view of a 56-year-old patient with marked loose festoons and deep nasojugal grooves. b Postoperative view 12 months after vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) procedure. Note the improvement of the malar bags

Fig. 16.

a Preoperative frontal view of a 58-year-old woman. She has marked malar festoons with ptosis of the malar tissues, hollowing of the infraorbital area and the cheek area, lengthening of the lower eyelid, attendant tear-trough deformity, and nasolabial grooves. b Postoperative view 6 months after a vertical upper-midface lift (SUM-lift) with improvement of the vertical height of the lower eyelid, reduction of the nasojugal groove, and enhancement of the malar festoons to a more youthful position, as well as increased malar projection

Discussion

Festoons typically contain muscle and skin invaginations and must be differentiated from malar bags, which are edematous sack regions bordering on the cheek aesthetic unit that accumulate fat or fluid with age [1, 2]. Loose festoons of the orbicularis muscle are occasionally the cause of baggy eyelids, adding their bulk to that of sagging intraorbital fat [1, 2]. This is seen mostly in older patients who have lax supporting structures in the preseptal area, orbital area, and the jugal region of the lower lid [1]. The striated muscle fibers of the orbicularis muscle are constantly active and could exacerbate the attenuation of the orbicularis muscle in the aging process [1]. If the muscle contracts, the festoons are affected and reappear as the muscle relaxes. In rare cases a lateral-based transposition of the orbicularis muscle flap for orbicularis suspension in lower blepharoplasty is used for treating malar bags. With controlled amounts of traction to the lower lid, it is possible to correct the lowest part of the orbicularis oculi muscle due to its concentrating actions and its major vertical vector of traction. However, it is seldom effective in the treatment of festoons in the long run because it does not improve permeability characteristics of the malar septum.

The question is: Which technique is most acceptable at the time? Knowing that gravity seems to have little effect on the development of malar mounds, the progressive distribution of skin and muscle due to chronic malar edema, malar festoon may be the end stage of the process [1, 2]. This is because the facial network originates at the level of the orbital rim and the malar septum acts as an impermeable membrane from the orbital rim to the cheek skin [2]. According to Pessa and Garza [2], the inferior border of the malar mound is created by dermal insertions of the inferior extent of the orbicularis muscle and that swelling in the malar mound region is primarily subdermal, forming festoons. Therefore, malar mounds tend to occur at a relatively constant location throughout life. Progressive distribution of skin results in the development of festoons because the facial fascia interdigitates with fibrous septa of the superior fascial cheek fat at the level of the orbicularis oculi as it crosses the muscles [2]. The malar septum, as described by Pessa and Garza [2], divides the suborbicularis oculi fat into superior and inferior compartments. The inferior compartment is confluent with the lower cheek fat and the superior compartment contributes to the formation of malar mounds. The superior compartment contains the suborbicularis oculi fat, the orbicularis muscle, the superficial cheek fat, and the cheek skin. Thus, in some patients the malar mounds may be affected by fluctuating edema which can progress to festoons. Regarding the findings of Pessa and Garza [2], it seemed evident that malar mounds, edema, festoons, and periorbital ecchymosis all occur in the same anatomic area. That means that the cutaneous insertion point occurs roughly 3 cm inferior to the lateral canthus. Therefore, in agreement with Glasgold et al. [5], we do not believe that it is effective to use a subciliary incision alone to lift and redrape malar mounds or festoons; we believe that these are most effectively treated by direct excision of distributed skin [5]. Concerning our findings, malar festoons seem to be correctable only if the malar septum is affected. This can be achieved by a vertical subperiosteal midface elevation, release and reset of the malar septum, and a controlled amount of traction of the orbicularis oculi muscle in conjunction with little lower-lid skin resection. By vertically elevating the soft tissue of the cheek and thus repositioning of the malar septum, tissue edema (malar festoons) above its cutaneous insertion will be resolved.

Conclusion

Subperiosteal vertical midface lift resuspends and redrapes the facial network that originates at the level of the orbital rim and seems to improve permeability characteristics of the malar septum, which is the membrane from the orbital rim to the cheek skin. It resolves the malar edema, the malar mounds, and the loose festoons by freeing the cheek tissue from underlying bone and repositioning the malar septum.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

J. F. Hoenig, D. Knutti, and A. de la Fuente have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Furnas DW. Festoons of orbicularis muscle as a cause of baggy eyelids. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:540–546. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pessa JE, Garza JR. The malar septum: the anatomic basis of malar mounds and malar edema. Aesthet Surg J. 1997;17:11–17. doi: 10.1016/S1090-820X(97)70001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossarie R, Leyder P. Which treatment for the malar bags? Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carriquiry CE, Seoane OJ, Londinsky M. Orbicularis transposition flap for muscle suspension in lower blepharoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57:138–141. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000218633.94036.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasgold M, Lam SM, Glasgold R. Volumetric rejuvenation of the periorbital region. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26:252–259. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besins T. The “R.A.R.E”. technique (reverse and repositioning effect): the renaissance of the aging face and neck. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:127–142. doi: 10.1007/s00266-004-3002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Fuente A, Santamaria AB. Endoscopic subcutaneous and SMAS facelift without preauricular scars. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23:119–124. doi: 10.1007/s002669900253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Fuente A, Hoenig JF. Video-assisted endoscopic transtemporal multilayer upper midface lift (MUM-Lift) J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:267–276. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuente del Campo A. Subperiosteal facelift: open and endoscopic approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995;19:149–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00450251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamra ST. The role of the septal reset in creating a youthful eyelid-cheek complex in facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;11:2124–2141. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000122410.19952.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamra ST. Continuing medical education article-facial aesthetic surgery: septal reset in midface rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2005;25:628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hester TR, Gordner MA, McCord CD, Nahai F, Giannopoulos A. Evolution of technique of the direct transblepharoplasty approach for the correction of lower lid and midfacial aging: maximizing results and minimizing complications in a 5-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:393–406. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little JW. Three-dimensional rejuvenation of the midface: volumetric resculpture by malar imbrication. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:267–285. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul MP. Transblepharoplasty subperiosteal forehead and midface lift. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez OM. Three-dimensional endoscopic midface enhancement: a personal quest for the ideal cheek rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:329–340. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200201000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson SW, Niamtu J, 3rd, Cunningham LL., Jr The endoscopic brow and midface lift. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2003;11:145–155. doi: 10.1016/S1061-3315(03)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]