Abstract

Suicide is a leading cause of death among older adolescents and young adults; however, few studies have prospectively examined risk for suicidal ideation. The present study in older adolescents and young adults investigated whether two personality traits previously implicated in risk for suicidal ideation, neuroticism and extraversion, as well as certain aspects of interpersonal functioning, prospectively predicted endorsement of suicidal ideation during depressive episodes. Participants (n=117) are a subset of the Northwestern-UCLA Youth Emotion Project sample, which started with a group of high school juniors oversampled for high neuroticism. Baseline interpersonal functioning was measured using the Life Stress Interview. Baseline personality trait composite scores were created from multiple inventories. Depressive disorders and suicidal ideation were assessed at the baseline and three annual follow-up interviews using the SCID. Cox regression was employed to predict suicidal ideation during depressive episodes diagnosed at any follow-up interview. Results showed that baseline extraversion inversely predicts suicidal ideation in males only, and that baseline interpersonal problems in one’s social circle, regardless of gender, predict suicidal ideation during depressive episodes.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, depression, neuroticism, extraversion, interpersonal functioning, adolescents, young adults

1. Introduction

Suicide is the third leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults between the ages of 15 and 24 in the United States (2006 data; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). In a cross-sectional sample of 5,877 individuals between the ages of 15 and 54, the highest risk per year for the onset of suicidal ideation occurred in the late teenage years and early twenties (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999). Thus, suicide and related behaviors are important public health issues, and research in adolescent and young adult samples is particularly consequential.

One such related behavior is suicidal ideation (SI). SI can range from passive wishes for one’s own death to outright planning of suicide and is indicative of risk for future suicide attempts. Indeed, in a prospectively followed community sample, those who endorsed SI at age 15 were more than 11 times as likely as their counterparts who denied SI to attempt suicide by the age of 30 (Reinherz, Tanner, Berger, Beardslee, & Fitzmaurice, 2006). SI is known to occur at greater rates in individuals diagnosed with depression (Garlow et al., 2008). Therefore, examining risk for SI within individuals with depression may provide etiological insights.

Finally, while cross-sectional research has identified several correlates of SI and other suicide-related behaviors, only prospective studies are able to determine risk factors that precede the development of SI. To our knowledge, only one other study has prospectively examined risk for SI among adolescents and young adults diagnosed with depression (Fergusson, Beautrais, & Horwood, 2003). This study examined risk for SI among 404 participants of the Christchurch Health and Development Study (CHDS) who were diagnosed with depression between 14 and 21 years of age (38% of 1,063 CHDS participants). Among other findings, those who endorsed SI between ages 14 and 21 scored higher on a neuroticism scale at age 14 than did those who denied SI. Here, we examine several potential risk factors for SI in a sample of older adolescents and young adults diagnosed with depression and drawn from a large, prospective longitudinal investigation of risk for emotional disorders at Northwestern University and UCLA—the Youth Emotion Project (YEP; Zinbarg et al., 2010).

1.1 Risk factors examined in the present study

The present study focused on two personality traits and several domains of interpersonal problems as possible risk factors for SI during depression. A recent review of personality correlates of suicidal behavior suggests that neuroticism and extraversion are associated with risk for SI (Brezo, Paris, & Turecki, 2006).

First, neuroticism (N) is a relatively stable, partially heritable personality trait associated with frequency of experiencing negative emotional states such as anger, sadness and anxiety (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1995). High N is theorized to increase propensity for negative reactions to life adversity (e.g., Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, 2004); such negative reactions may include suicidal ideation. N is positively associated with risk for depression (e.g., Kendler et al., 2004) and with risk for SI in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, though few studies controlled for depression diagnoses. For example, N was associated with current SI, but not lifetime or past SI in the National Comorbidity Survey sample of 5,877 individuals (Cox, Enns, & Clara, 2004). More importantly, in a longitudinal study of 5,995 individuals from unselected twin pairs, baseline N was one of several significant predictors of lifetime SI and suicide attempts 11–13 years after the baseline assessment (Statham et al., 1998). As described above, N was also a risk factor for SI within individuals with depression in the CDHS (Fergusson et al., 2003). Taken together, these provide evidence of a relationship between N and SI.

Second, extraversion (E) is a relatively stable, partially heritable trait associated with characteristics such as warmth, gregariousness, and positive emotions (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1995). Although E has not been investigated as a risk factor for SI as often as has N, evidence suggests that E may be inversely related to SI. Indeed, positive emotions associated with high E are theorized to buffer individuals from the negative effects of life adversity (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003), and E prospectively predicts perceived social support (Von Dras & Siegler, 1997), both of which may increase resilience against suicidal ideation. Several longitudinal studies have found that E is inversely associated with depression (e.g., Hirschfeld et al., 1989; Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, Silva, & McGee, 1996) though others failed to replicate these findings (e.g., Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath, & Eaves, 1993). Among cross-sectional studies, one found that among 462 primary care patients age 65 and older, individuals with SI scored lower on a measure of E than those who denied SI (Hirsch, Duberstein, Chapman, & Lyness, 2007). Taken together, these reports support the inclusion of E as a potential risk factor for SI in longitudinal studies. No prospective studies have been reported yet on whether E inversely predicts SI.

Finally, measures of interpersonal functioning were included as risk factors in this study. Moreover, interpersonal problems (cf., social alienation, low belonging), which may reflect important unmet needs for affiliation, are theorized to increase risk for suicidal ideation (e.g., Joiner et al., 2009). Such problems have been associated with a lifetime history of suicide attempts among methadone users (Conner, Britton, Sworts, & Joiner, 2007) and with completed suicide in a post-mortem case-control study (Boardman, Grimbaldeston, Handley, Jones, & Willmott, 1999). One prospective study found that several types of interpersonal problems during adolescence predicted endorsement in young adulthood of previous suicide attempt(s) (Johnson et al., 2002).

The goal of the present study was to examine our hypothesis that N, E and interpersonal problems would independently, prospectively predict SI during depressive episodes. Given abundant evidence of gender differences in other aspects of suicidal behavior—e.g., rates of suicide attempts versus completions (Hawton, 2000) and risk factors for suicide attempts (Oquendo et al., 2007)—we explored whether gender might moderate these risk factors. However, because there was no evidence to suggest how the genders might differ in this regard, we did not make specific predictions about the nature of moderation.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Data for the current study were collected as part of the YEP, a two site longitudinal investigation examining risk factors for internalizing disorders. A complete description of YEP participants and recruitment procedures is provided by Zinbarg, Mineka, Craske and colleagues (2010). In brief, over 1,900 high school juniors were screened for N using the Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ-R-N; Eysenck, Eysenck, & Barrett, 1985). Those scoring high on this measure were oversampled, comprising 59% of the final group of 627 who consented and completed the described baseline diagnostic interviews, life stress interviews and questionnaires. Participants were asked to repeat all measures on an annual basis.

The current study employs data from the baseline assessment and three annual follow-up assessments. Participants included here completed the baseline questionnaires and met criteria for a clinically significant, unipolar, episodic depressive disorder (DD) during one or more of the years covered by the three follow-up assessments. A total of 90 females and 27 males fulfilled these criteria (total n=117). Particpants’ mean age at baseline was 16.94 (SD=0.36) and Caucasians comprised 58.12% of this sample, which was, on average, upper middle class based on Hollingshead SES scores (M=50.62, SD=11.74; Hollingshead, 1975). Individuals with a history of DD or SI at baseline were not excluded; instead these clinical variables were tested as predictors, as reported below.

2.2 Measures and Assessment Procedures

2.2.1 Depressive Disorders

Diagnoses of clinically significant unipolar DD’s were assigned using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, non-patient edition (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001). While the baseline SCID assessed lifetime psychopathology, annual follow-up SCID’s only assessed psychopathology occurring during the time period since the participant’s last assessment. Interviewers were blind to past diagnoses. Inter-rater reliability was assessed for approximately 10% of all SCID’s. Across all assessment periods reported here, kappa for interviewers’ diagnoses of clinically significant MDD ranged from .65 to .84 (M=.75, SD=.10). DD’s examined include DSM-IV manifestations of MDD and depressive disorder, not otherwise specified (DD-NOS) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Only episodic cases of DD-NOS (i.e., not Dysthymic Disorder) were included in the present report because SI is only assessed in the Major Depressive Episode section of the SCID.

2.2.2 Suicidal Ideation

Whether SI was present during a depressive episode was determined by examining the symptom-level data from the SCID. All participants endorsing symptoms of a major depressive episode were asked the following questions with regard to the worst two weeks of the episode: “Were things so bad that you were thinking a lot about death or that you would be better off dead? What about thinking of hurting yourself?” Participants endorsing SI within the past month received additional assessment to ensure their imminent safety.

2.2.3 Personality and Mood Composites

Baseline N composite scores were calculated using the average of z-scores on four scales: the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised Neuroticism Scale (EPQ-R-N; Eysenck, Eysenck & Barrett, 1985), the IPIP NEO Revised Personality Inventory (IPIP NEO-PI-R; Goldberg, 1999), the Behavioral Inhibition Scale (BIS) from the Behavioral Inhibition Scale/Behavioral Activation Scale (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994), and the Big Five Mini-Markers Neuroticism Scale (Saucier, 1994). Baseline E composite scores were also calculated in this manner using three scales: the Big Five Mini-Markers Extraversion Scale (Saucier, 1994) and the Reward Responsiveness and Drive subscales of the BIS/BAS (Carver & White, 1994). The BAS Fun Seeking subscale was not administered. All items from these scales were included, except two items from the EPQ-R-N, as previously described (Zinbarg et al., 2010). A baseline depression symptom composite was also calculated (Zinbarg et al., 2010).

2.2.4 Interpersonal functioning

The Life Stress Interview (LSI; Hammen et al., 1987) is a semi-structured interview designed to objectively assess, in part, chronic life stress across multiple domains. The current study utilizes baseline severity ratings of chronic interpersonal stress in all four such LSI domains: best friend, social circle, romantic relationships, and family. Interviewers rated participants’ levels of chronic interpersonal stress since the previous assessment on a scale from 1 (exceptionally positive conditions) to 5 (worst conditions imaginable). Approximately 10% of interviews were scored by a second rater blind to the interviewer’s ratings, allowing estimation of within-site (ICC’s of .73, .83, .63, .82) and cross-site (ICC’s of .76, .82, .61, .76) reliability for the four domains, respectively.

2.3 Statistical Procedures

Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Analyses employed the Cox regression model (proportional hazards modeling, a type of survival analysis) (Singer & Willett, 2003). This model accommodates variation in the number of assessments included for participants; such variation was inevitable given that each participant was only included in the model for the timepoint(s) in which s/he experienced a DD. The model included time-variant predictors (e.g., whether the diagnosis was MDD or DD-NOS) as well as time-invariant predictors (e.g., baseline personality measurements). Effect sizes are given as hazard ratios (HR), which represent the difference in the amount of risk per time point (hazard) associated with any one-unit increase in the value of the predictor (p. 527, Singer & Willett, 2003). Once an individual endorsed SI, future waves of data for that participant were censored to prevent individuals with repeated SI from being overly influential. P-values < .05 are considered statistically significant; p-values between .05 and .10 are noted as approaching significance.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics, demographics and clinical variables

Personality composite variables were examined to rule out the possibility that selection of individuals with DD’s truncated or skewed their distributions, which might increase the likelihood of Type II error. Both N and E composites were normally distributed and slightly restricted in range, relative to the full YEP sample (respectively: Kolmogorov-Smirnoff Z values of .77 and .57, both NS, and ranges of −1.55 to 2.37 and −2.53 to 1.67, akin to z-scores). Correlations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations and odds ratios for baseline predictors and follow-up clinical variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r’s | |||||||||||||

| 1. SES | |||||||||||||

| 2. N | .02 | ||||||||||||

| 3. E | .01 | −.09 | |||||||||||

| 4. Dep | −.13 | .59 | −.28 | ||||||||||

| LSI Interpersonal Problems | |||||||||||||

| 5. Best Friend | −.29 | .17 | −.28 | .18 | |||||||||

| 6. Social Circle | −.22 | .20 | −.25 | .31 | .50 | ||||||||

| 7. Romantic | −.06 | .31 | −.15 | .32 | .24 | .24 | |||||||

| 8. Family | −.16 | .04 | −.08 | .31 | .13 | .31 | .21 | ||||||

| Odds Ratios obtained using logistic regression | |||||||||||||

| 9. Male | 1.01 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.86 | 1.32 | 1.62 | 0.60 | 0.61 | |||||

| 10. Caucasian | 1.08 | 1.45 | 1.09 | 1.47 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 1.25 | 0.74 | 1.16 | ||||

| 11. History of DD | 0.97 | 1.22 | 0.58 | 1.33 | 1.73 | 2.10 | 1.63 | 1.65 | 1.31 | 0.67 | |||

| 12. History of SI | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 1.48 | 1.67 | 0.35 | 3.21 | 0.92 | 0.41 | -- | ||

| Hazard Ratio obtained using Cox regression | |||||||||||||

| 13. MDD vs. DD-NOS | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.46 | 1.01 | |

| 14. SI at follow up | 1.02 | 1.08 | 0.67 | 1.11 | 1.16 | 1.49 | 1.32 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.28 | 1.41 | 1.40 | 3.98 |

Note: Statistically significant (p <.05) r-values, OR’s, and HR’s are bolded above.

r’s = Pearson correlation coefficients; OR’s = odds ratios; SES = Socioeconomic Status; N = Neuroticism composite; E = Extraversion composite, Dep = Baseline depression composite score.

Of the n=58 individuals with historical or current DD at baseline, n=28 (48%) endorsed SI during one or more historical or current DD’s.

Demographic variables (gender, race/ethnicity, SES) did not predict SI in separate Cox regression models (all χ2(1)≤1.52, NS). Similarly, clinical variables (baseline depression composite, baseline history of a clinically significant DD, baseline history of SI during a DD, whether the follow-up diagnosis was MDD or DD-NOS) did not predict SI (all χ2(1)≤2.35, NS).

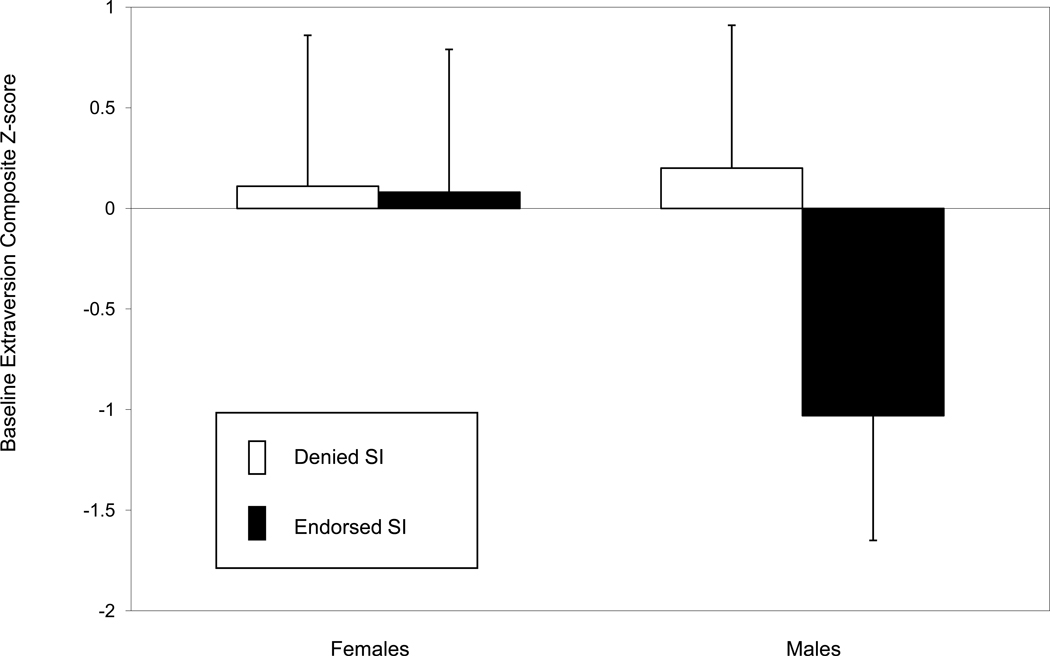

3.2 Personality traits

In aggregate, baseline E inversely predicted SI in males only, while baseline composite N was not significantly related to SI for either gender. More specifically, gender and N scores were simultaneously entered in the first block and the N × Gender interaction was entered in the second block, with SI as the dependent variable. This model was not significant (Table 2). By contrast, when gender, E and their interaction were examined in the same fashion, the E × Gender interaction significantly predicted SI (Table 2). The data were examined separately by gender to decompose the interaction. E inversely predicted SI in males (χ2(1)=9.42, p<.01; b=−1.28, SE(b)=.46, HR=.28, 95% CI [0.11, 0.68]), but not in females (χ2(1)=0.00, NS, b=.002, SE(b)=.31, HR=1.002, 95% CI [0.55, 1.83]; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Results of select Cox regression models

| Overall χ2(df) |

Change χ2(df) |

b(SE) | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Composite & Gender | ||||

| Block 1: Gender, N Composite | 0.26(2) | -- | -- | -- |

| Block 2: E × Gender | 2.59(3) | 2.12(1) | ||

| N | −.14(.28) | 0.87(.50–1.50) | ||

| Gender | −.20(.51) | 0.82(.30–2.20) | ||

| N × Gender | .68(.46) | 1.97(.79–4.91) | ||

| E Composite & Gender | ||||

| Block 1: Gender, E Composite | 3.16(2) | -- | -- | -- |

| Block 2: E × Gender | 10.13(3)* | 5.96(1)* | ||

| E | .00(.31) | 1.00(.55–1.84) | ||

| Gender | −.68(.63) | 0.50(.15–1.75) | ||

| E × Gender | −1.30(.56)* | 0.27(.09–.82) | ||

| Three E Subscales in Males Only | ||||

| Simultaneous entry | 13.03(3)** | -- | ||

| Big 5 MM E | −.91(.38)* | .40(.19–.85) | ||

| BAS Drive | −.85(.51)‡ | .43(.16–1.17) | ||

| BAS Reward Responsivity | .07(.40) | 1.08(.49–2.35) | ||

p <.10,

p <.05,

p <.01.

Note: Big 5 MM = Big Five Mini Markers

Figure 1.

Baseline extraversion score by gender and follow-up suicidal ideation (SI). Of the 117 participants studied, n = 22 females (24.4%) and n = 8 males (29.6%) endorsed SI during a follow-up DD.

To determine whether the effect was attributable to certain scales of the E composite, the three scales were entered in a model including males only. Results showed that the Big Five Mini Markers Extraversion scale inversely predicted SI, and the BAS Drive subscale approached significance as an inverse predictor (Table 2). To determine whether the effect of E on SI in males with DD’s could be accounted for by interpersonal problems, E and the four domains of interpersonal problems were entered simultaneously in a Cox regression model. E remained a significant predictor of risk (b=−2.79, SE(b)=1.41, p<.05, HR=.06, 95% CI [0.004, 0.98]).

3.3 Interpersonal problems

In aggregate, the results showed that interpersonal problems within one’s social circle predicted SI regardless of gender. More specifically, separate Cox regression models predicting SI during DD were examined for each interpersonal domain: best friend, social circle, romantic and family relationships. Models including gender demonstrated no significant main effects or interactions with gender (for blocks adding gender, χ2’s(1)≤1.38, NS, with the exception of Gender × Romantic Relationships, which approached significance, χ2(1)=2.81, p=.095). Thus, the analyses of interpersonal problems are reported without gender. Interpersonal problems in the social circle domain predicted SI (χ2(1)=4.09, p<.05 b=.40, SE(b)=.20, HR=1.49, 95% CI [1.01, 2.21]). No other interpersonal domains of the LSI predicted SI (all χ2(1)≤0.89, NS). When all four domains were entered in a model, social circle’s effect size was slightly larger than previously (HR=1.55) and approached significance (p=.064). Therefore, although including all domains reduced power, other domains of interpersonal problems did not account for the effects of the social circle domain.

4. Discussion

The results showed that E inversely predicted SI among males only, and that interpersonal problems in one’s social circle predicted SI regardless of gender. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective demonstration that E is a risk factor for SI. In contrast, N did not significantly predict SI.

4.1 Non-replication of N as a predictor of SI

Given N’s well-established association with risk for an array of symptoms and mental disorders, and the research reviewed above linking it with risk for SI, it was surprising that N did not significantly predict SI. However, only one prospective, longitudinal study has examined the effects of N on risk for SI among individuals with DD’s (Fergusson et al., 2003). One possibility is that our finding represents a Type II error, given several considerations. First, our depressed sample during the prospective period is relatively small (n=123 of which n=117 met inclusion criteria; 20% of 627 total participants) compared with that of Fergusson and colleagues (n=404; 38% of 1,063 total participants). Second, the range of N was reduced compared to the full YEP sample; however, one would expect a similarly restricted range of N in any depressed sample. Third, our dichotomous dependent variable may also constrain power to detect a relationship with N. Alternatively, N may spuriously appear to predict SI in other studies, since it is a strong predictor of DD’s, within which SI occurs at substantially elevated rates. It might be that Fergusson et al. diagnosed some subclinical cases with full MDD, and that in their sample, N predicted true full MDD, making N appear to predict SI.

4.2 Possible explanations for E × Gender interaction

We had not predicted a priori that E would inversely predict SI in males only. Possible explanations could be that E is more closely related to one or more mediating variables for SI in males than in females, such as aspects of interpersonal or cognitive functioning. However, baseline interpersonal problems did not account for the relationship between E and SI in males (see 3.2). Gender differences in interpersonal functioning related to E might be more subtle than our measure captured, or might manifest temporally closer to depression onset. Males are less likely than females to seek out social support during a period of stress (Eagly & Crowley, 1986), and males report lower perceived social support than females (Turner & Marino, 1994). Thus, when depressed, males low in E may seek out even less support than usual and may feel more socially isolated than their female counterparts, which in turn may heighten their risk for SI.

In addition to interpersonal functioning, cognitive functioning might mediate the relationship between E and SI in males. Positive affect, more frequently experienced in those with higher levels of E, has also been associated with cognitive flexibility (e.g., Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). Further, cognitive inflexibility (cf., problem-solving deficits) has long been implicated as a cognitive risk factor for suicidal behavior (for a review, see Ellis & Rutherford, 2008). It may be that individuals lower in E manifest more rigid thinking patterns, compromising consideration of a full range of outcomes. Positive outcomes may be particularly difficult to conceive of, increasing the likelihood of SI. Why males might be more vulnerable than females to such effects is unclear.

4.3 Limitations

Despite several strengths of this study, notably the prospective design, the use of structured clinical interviews, and the ability to control for depression diagnoses, the study has several limitations. First, to rule out the possibility that previous DD or SI influenced baseline personality or interpersonal problems, it would be ideal to exclude individuals with a history of DD or SI at baseline; however, very few prospective studies of SI can do so. Second, these results are limited to individuals diagnosed with DD’s because the study does not include a stand-alone measure of SI. Thus, it is unclear to what extent these findings may generalize to other clinical conditions and to individuals diagnosed with DD’s, who are between episodes. Third, a continuous measure of SI may be preferable to the SCID item used here to assess SI. However, this concern may be mitigated because interviewers are able to follow-up incomplete responses to ascertain SI. Finally, it is possible that higher severity of depression is predicted, not specifically SI. The importance of identifying predictors of SI even if they are confounded with depression severity may attenuate this concern. Given the limited prospective research on this topic, the present findings may represent significant progress.

4.4 Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that among older adolescents and young adults experiencing depression, E inversely predicts SI in males, and interpersonal problems in one’s social circle predict SI regardless of gender. While it is prudent for clinicians to carefully assess SI in all depressed individuals, clinicians may expect greater likelihood of SI in adolescents and young adults with weaker peer networks and in males with low extraversion.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest: This research was supported by a two-site grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to S. Mineka and R. Zinbarg (R01-MH065652) and to M. Craske (R01-MH065651). The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman A, Grimbaldeston A, Handley C, Jones P, Willmott S. The North Staffordshire Suicide Study: A case–control study of suicide in one health district. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29(01):27–33. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(3):180–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Conner K, Britton P, Sworts L, Joiner T. Suicide attempts among individuals with opiate dependence: The critical role of belonging. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(7):1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64(1):21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox B, Enns M, Clara I. Psychological dimensions associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34(3):209–219. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.3.209.42781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly A, Crowley M. Gender and helping behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;100(3):283–308. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.100.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis T, Rutherford B. Cognition and suicide: Two decades of progress. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1(1):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Beautrais A, Horwood L. Vulnerability and resiliency to suicidal behaviours in young people. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(1):61–73. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders-non-patient edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion. 2005;19(3):313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B, Tugade M, Waugh C, Larkin G. What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow S, Rosenberg J, Moore J, Haas A, Koestner B, Hendin H, Nemeroff C. Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(6):482–488. doi: 10.1002/da.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Adrian C, Gordon D, Burge D, Jaenicke C, Hiroto D. Children of depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptom predictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96(3):190–198. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K. Sex and suicide: Gender differences in suicidal behaviour. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(6):484–485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J, Duberstein P, Chapman B, Lyness J. Positive affect and suicide ideation in older adult primary care patients. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22(2):380–385. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld R, Klerman G, Lavori P, Keller M, Griffith P, Coryell W. Premorbid personality assessments of first onset of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46(4):345–350. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810040051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Cohen P, Gould M, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook J. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):741–749. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Van Orden K, Witte T, Selby E, Ribeiro J, Lewis R, Rudd M. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Kuhn J, Prescott C. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):631–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Neale M, Kessler R, Heath A, Eaves L. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(11):853–862. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Borges G, Walters E. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R, Caspi A, Moffitt T, Silva P, McGee R. Personality traits are differentially linked to mental disorders: A multitrait-multidiagnosis study of an adolescent birth cohort. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:299–312. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Bongiovi-Garcia ME, Galfalvy H, Goldberg PH, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Sex differences in clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression: A prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):134–141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz H, Tanner J, Berger S, Beardslee W, Fitzmaurice G. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1226–1232. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G. Mini-Markers: A Brief Version of Goldberg s Unipolar Big-Five Markers. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;63(3):506–516. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Willett J. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. USA: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Statham D, Heath A, Madden P, Bucholz K, Bierut L, Dinwiddie S, Martin N. Suicidal behaviour: An epidemiological and genetic study. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(04):839–855. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R, Marino F. Social support and social structure: A descriptive epidemiology. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;35(3):193–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Dras D, Siegler I. Stability in extraversion and aspects of social support at midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(1):233–241. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg R, Mineka S, Craske M, Griffith J, Sutton J, Rose R, Waters A. The Northwestern-UCLA youth emotion project: Associations of cognitive vulnerabilities, neuroticism and gender with past diagnoses of emotional disorders in adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(5):347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Web References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 10-year age groups, by race and sex: United States, 2006. 2009 Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK2_2006.pdf.