As the number of people with heart failure continues to increase, more patients and their caregivers are faced with needs related to uncertainty and the unpredictable nature of living with heart failure. One way to meet the needs of heart failure patients and their caregivers is through the delivery of palliative care that is provided in response to assessed needs.1 Healthcare professionals agree that heart failure patients need supportive care, typically bundled as palliative care, however, inconsistencies remain in the scope and timing of targeted palliative care interventions. Palliative care remains underutilized with heart failure patients and their families, often only introduced near the end of life rather than at the time of diagnosis.2 Likewise, palliative care is often associated with comfort care at the end of life, and because of that misconception, it is not requested by families early on in the course of a life limiting illness such as heart failure.3

Palliative care is more than just comfort care at the end of life; it encompasses a myriad of needs in addition to managing pain and comfort and should begin early in the course of a life-limiting illness.4 According to the National Consensus Project (NCP),5 palliative care includes an interdisciplinary assessment and attention to physical symptoms, psychosocial concerns, spiritual concerns, cultural needs, medication management, financial concerns, and support of family goals for care. Furthermore, researchers have suggested that palliative care should be provided according to patient and family needs2 and in response to the heart failure illness trajectory.1 Therefore, it is important to consider the experience and needs of the family caregivers, such as spouses, as well as the needs of the heart failure patient in planning palliative care interventions throughout the illness trajectory.

There are numerous studies published about the experiences of patients and caregivers living with heart failure and the needs of informal caregivers.6–10 Nonetheless, little is known about the experience and needs of the spousal caregiver prospectively and longitudinally over the experience of caring for a husband or wife with heart failure. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to report the findings of two recent studies of spouses’ experiences of caring for their loved one with heart failure followed at specialized heart failure centers and their identified needs within the context of the dynamic ebb and flow of living with heart failure.

Background

The experience of living with heart failure and caring for someone with heart failure has been explored through qualitative research, however, few studies report longitudinal data to describe the experience over time. Aldred, Gott, and Gariballa11 explored the impact of advanced heart failure on older patients and their caregivers through joint interviews with 10 couples. Their findings revealed the negative impact that heart failure has on everyday life and relationships. Lack of support from health care professionals and poor coordination between primary and secondary care providers were reported. They suggest the need to further investigate the perceived needs of people with heart failure rather than rely on health professionals’ definition of what their needs might be.

Luttik and colleagues7 conducted a study with partners of heart failure patients in order to describe the experiences of caring for a partner with heart failure and to explore the factors that influence caregiver well-being. Thirteen participants were interviewed once with questions targeted at the course of heart failure, changes in life, the impact of heart failure on the marriage relationship, and potential needs. Reported themes were changes in life, anxiety, support from their environment and heart failure professionals, and coping. One key finding under support was the perception that they did not feel involved with or acknowledged by the health care professionals, citing the need for increased information especially during times of crisis.

Davidson, Cockburn, and Newton12 studied the prevalence of needs in 132 patients with heart failure within 30 days of hospital discharge using the Heart Failure Needs Assessment Questionnaire. Needs were categorized into four domains: Physical, Existential, Social, and Psychological. Although needs were reported in every domain, they were ranked highest within the domains of psychological and social, with the greatest need being related to anxiety and motivation. No correlation was noted between any of the demographic variables with the domain scores, suggesting that it is not possible to predict needs based on their clinical and social profile. Likewise, researchers suggested that post-hospitalization was a time of particular vulnerability when psychosocial and existential needs prevail over physical needs.

Harding and colleagues13 conducted semi-structured interviews with heart failure patients, families, cardiology staff, and palliative care staff to inform policy guidelines regarding the communication and information needs of heart failure patients. Information needs emerged in the following categories: heart failure symptoms and management, disease progression, inadequate information, barriers to ineffective information, and recommendations for improvement. In general, the patients interviewed for this study reported limited knowledge about heart failure symptoms and management. Likewise, none of the patients or their caregivers had discussed expectations about disease progression or end-of-life preferences with their health care providers, suggesting a serious void in addressing the palliative care needs of heart failure patients. Importantly, the cardiology staff who were interviewed for this study admitted focusing on the technological aspects of the disease at the expense of overlooking the psychological needs of patients and their families.

Family caregivers for patients with heart failure play an increasingly important role as the condition of the person with heart failure begins to slowly decline. Spouses remain a major source of support as partners in care for persons with heart failure, yet few studies have explicated the experience of the caregiver, in particular over the course of the illness. In addition to coping with physical symptoms of heart failure, spouses are dealing with anxiety caused by uncertainty about the future, a loss of control over life, and grief over the loss of the patient’s health status.7 Spousal caregiving in heart failure is burdensome and stressful, accompanied by a change in roles, changes in daily life activities, and changes in relationships.7 Additionally, when informal caregivers of heart failure patients are under-supported, it may impact the outcomes for older patients with heart failure.14

The concept of caregivers as care recipients, thus also in need of palliative care interventions, is particularly salient to families caring for heart failure patients. Involving both the patient and the spousal caregiver in communication and care decisions has been shown to improve heart failure self-care.15 In fact, spouses describe their caregiving experience as positive when they were given attention, offered information, and recognized as strong and valuable by the patient. Likewise, negative experiences in heart failure caregiving were related to receiving insufficient support and being kept at a distance by the patient.16

The significance of these studies is underscored by research indicating that the family’s personal concerns, importance in care delivery, and impact on patient outcomes are not considered by health care providers, other family members, and friends.16–22 Yet, research has demonstrated that family caregivers are a significant factor in patient outcome. A study of the emotional well-being of 103 heart failure patients and their caregivers revealed that the caregivers’ perception of their own emotional well-being was a predictor of the patients’ well-being.18 Similar results were found in a study of caregivers and patients who were receiving intravenous infusions of medications for advanced heart failure; the caregivers’ mental status and perceptions of esteem influenced patients’ perceptions of health-related quality of life.7 Therefore, the intent of the research reported here is to fill the gap in our knowledge about the experiences of spousal caregivers over the course of 12–18 months of caring for a patient with heart failure in order to identify critical variations in palliative care needs across the heart failure illness trajectory.

Methods

Hupcey and colleagues conducted two studies of spouses of heart failure patients followed at specialized heart failure centers over the course of 12–18 months. Grounded theory methods were used to collect and analyze data in both studies. The initial study (NIH/NINR:1R15NR009976) included 27 wives of patients (≤65 years old) with advanced heart failure followed between 12 to 18 months or until the death of the husband. This study yielded the core variable of “achieving medical stability.”23 Next, these data were combined with a second longitudinal study (American Heart Association, Pennsylvania/Delaware Affiliate, Grant-in-Aid Program) of 18 spousal caregivers of older patients (≥ 62) with heart failure followed at two specialized heart failure centers in order to describe variations in palliative care needs over the course of caring for a spouse with heart failure.

Data Collection and Analysis

Following University IRB approval, the participants (n=45) were asked to participate following their spouse’s hospitalization or another type of acute heart failure event. The first interview was done in-person, with subsequent interviews either by phone or in-person when the spouse was readmitted or during a clinic visit. The goal was to interview participants monthly for 12 interviews. Twelve to 18 months were required to complete all 12 interviews. Overall, participants were interviewed one time (two participants) through 12 times or until the death of the spouse. Thirty-seven participants completed the whole series of interviews.

The interviews, which were open-ended, focused on the experience of caring for a spouse with heart failure and the changing needs of both the patient and caregiver over the course of the 12–18 months. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim with identifiers removed. The two data sets were analyzed for identification of the major needs reported by the spousal caregivers over the course of the study, with particular attention to the nature, timing, and scope of palliative care needs in relation to the husband’s or wife’s heart failure illness experience. This paper reports the major themes of the needs reported by spouses in accordance with the exacerbations/medical instability and times of medical stability over the 12–18 months.

Sample

A total of 45 spouses of patients with advanced heart failure were included. Thirty-nine of the spousal caregivers were females and six were male. They ranged in age from 27–76 (mean= 60, SD 9.3). The patients ranged in age from 31–79 (mean 61, SD 9.3). Time since initial diagnosis of heart failure ranged from 4 months to 20 years. Thirty-four of the patients with heart failure retired early as a result of the illness, contributing to major financial issues for 22 families. Over the course of the studies, 10 of the husbands/wives with heart failure died.

Findings

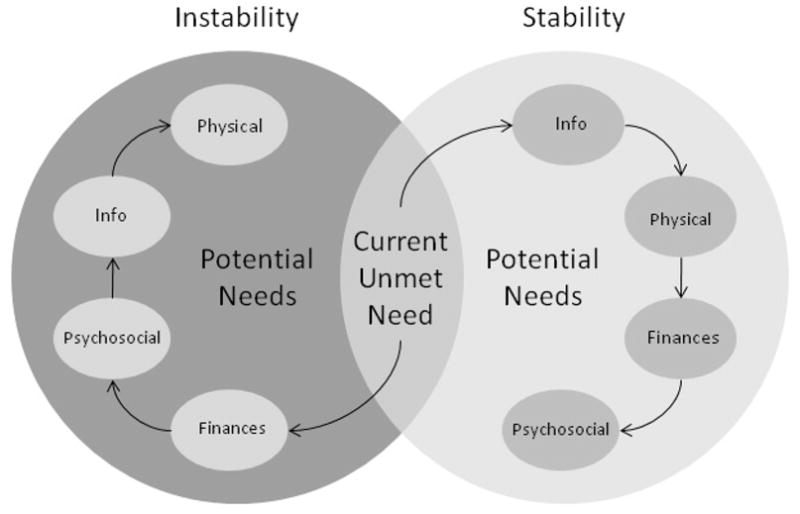

There was four categories of overarching needs/issues amenable to palliative care interventions expressed by spousal caregivers: informational needs, financial issues, psychosocial issues, and physical issues (see Table 1). It was discovered that needs of spousal caregivers were always present but changed according to the nature and course of the spouse’s heart failure trajectory. Certain needs were greater during times of exacerbation or medical instability, requiring hospitalization or instability at home, while other needs were more urgent during times when the patient with heart failure was considered medically stable. Thus, there was a continual reprioritization of the needs in response to the heart failure experience. Each of the four identified categories of palliative care needs/issues will be described according to occurrence during times of heart failure exacerbations/medical instability and during the periods of medical stability. Although the times of instability and stability are described separately, in actuality, these states are quite fluid, thus there may be overlap throughout the heart failure trajectory, as depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Spousal Palliative Care Needs in Heart Failure

| Exacerbation/Times of Medical Instability | Times of Medical Stability | |

|---|---|---|

| Informational Needs |

|

|

| Financial issues |

|

|

| Psychosocial Issues |

|

|

| Physical Issues |

|

|

Figure 1.

A Model of Spousal Palliative Care Needs inHeart Failure

Informational needs

All of the spousal caregivers had unmet informational needs, even those who were “experts” at caring for the spouse with heart failure. Since heart failure is a progressive disease, there were always additional devices and medications, so caregivers continuously had something new to learn. When an exacerbation occurred, the informational needs of spousal caregivers were focused on the here and now. They wanted easily understandable information regarding treatment options, advance directives, and information required to make immediate decisions while their spouse was hospitalized or during times when they were medically unstable at home. Informational needs were reprioritized during times of medical stability, but were just as important. They now focused on future planning, new drug or treatment regimens, diet management, and the information needed to make decisions about the care they were providing.

Exacerbation

When an exacerbation occurred, spousal caregivers wanted information about the present situation in terms they could understand. “I mean, when you talk to them, they have a language all their own. They never talk to the real people in English.” Caregivers reported wanting frank and honest appraisals of the spouse’s prognosis, and what to do if immediate medical care was needed. This issue was especially salient when care needed to be coordinated between hospitals, when in some cases the tertiary referral center was hours away.

I am not sure which hospital to go to. I guess if he has an episode or whatever we take him to the local hospital, I guess unless it’s the defibrillator, then I guess he would go to (local) hospital for that but then they would transfer him to (large medical center) if it was more than that… Medical Stability

Informational needs were a persistent theme throughout times of medical stability as expressed by a caregiver whose spouse had an internal cardiac defibrillator.

When he first had it (ICD) put in and for the first year, we’d go down and get readings and they’d say ‘no episodes’ and I thought ok, that must be good. But then in the back of my mind I’m saying what does that mean? Does that mean he is gonna keep getting worse?

Likewise, one spouse who lived several hours from the major heart failure center shared that she needed information in order to inform her decisions about when to call the doctor, especially when they sought treatment at a local hospital.

Maybe I shouldn’t feel this way, but I feel like I shouldn’t have to call the doctor for every little thing, but when you don’t know when to call and I’m stressed because I’m thinking he has this heart condition and now he has a cold…so I think they could do a better job at stuff like that…I mean really the medical profession should be giving people information.

Even the very basic need of knowing how to resuscitate if the need arose was not always discussed with the wives.

If something were to happen to him where we couldn’t get medical help or whatever, I really had no clue what to do except for eventually he (husband) said, “Don’t give me CPR because I have an internal device and that would be worse. Or don’t put paddles on me.” So, some kind of training about how to take care of your spouse in certain situations would be good.

Financial Issues

Not all of the families had financial issues; but for the families that did, these concerns were omnipresent. When heart failure occurred at an early age, resulting in premature retirement, couples faced greater financial issues. Some older couples also struggled, particularly with the cost of medications. During times of heart failure exacerbation many of the financial issues that were present during periods of medical stability escalated. Worries about the future, such as who was going to pay the hospital bill or what expensive medications were being added to the medical regimen, were not top priorities. During exacerbations, the primary concern was to have the patient become stable once again. For many spousal caregivers, other financial issues became a major concern during exacerbations requiring hospitalizations or frequent clinic visits. Because most couples lived quite far from the heart failure centers, spouses had to commute a long distance or pay for local lodging near the medical center during times of exacerbations that required hospitalization. During times of medical stability, caregivers voiced concerns about different financial issues, such as receiving disability and how they would afford the cost of additional medications. Although many of the patients received disability benefits, many caregivers needed to work outside the home for extra income and/or insurance coverage. Some of the caregivers in this study did not have health insurance for themselves.

Exacerbation

Caregivers employed outside the home had to miss work to care for their spouse during exacerbations. This resulted in a greater financial burden for the family and for many, resulted in lost income and in some cases losing their job and/or their home. One wife said:

I had my own business, but I couldn’t be there. I was the boss and I couldn’t be there and I couldn’t depend on my employees to do what I needed to do and so after going through so many hospital visits and so many hospital stays I just finally said “I got to close, I can’t do this”.

Another caregiver described her inability to afford to stay near the hospital:

Unless he’s really, really sick I don’t stay down there. I mean if I know he’s having a real hard time I don’t come home, but I travel a lot when he’s in the hospital. I don’t like it, but I do it….I’d rather stay, but I know that I can’t afford to so. Now I’ve already slept in my car….

Medical Stability

Caregivers reported the need for help in finding resources to help pay for expensive medications, especially when their spouse hit the “doughnut hole.”

We are now in the doughnut hole, which means $400 per month for medicine. We will be in the hole for August-December. Our sons want to bail us out some on the doughnut hole. They think we are destitute. I said, “Oh my word not we are not destitute yet boys.” But we are considering a reverse mortgage on our house to cover our med expenses. And I am considering getting a job and I have always been a housewife but $400 a month is a lot of extra money on a fixed income.

Likewise, several caregivers shared their difficulty in navigating through the process of filing the disability paperwork and then making ends meet during the 6-month waiting period for the first disability check. “According to what the doctors were saying, we applied for disability. It took a while to get that. In the meantime we lost our home.”

The lack of health insurance for spousal caregivers was also a major issue. One wife described the lack of health insurance and its impact on her own health.

I can’t even get sick. I can’t afford it. One day I got a bladder infection. The doctor said that he needed to put me in the hospital because I was so sick. I said, “I don’t care, I can’t afford it.”

Psychosocial Issues

Psychosocial issues were present for all spousal caregivers; even caregivers with strong family support systems felt the burden of caregiving fell on them alone. For some caregivers, these issues were especially prominent during times of exacerbation requiring hospitalizations and the unstable period that followed. The lack of family available during times of exacerbation was described as “difficult for me as a caregiver.” One common theme even when they had family living nearby was “we do not like to bother them as they (the children) have their own busy lives.” But even during times of medical stability, psychosocial issues were present. Some of these issues were very fundamental and practical and often related to role change when caregivers were faced with doing the work their spouse could no longer physically tolerate. For instance, cutting the grass, shoveling snow, or caring for house and car maintenance were new skills for many of the spousal caregivers. Another important issue related to the lack of support for the spousal caregiver by family and friends. During this time family/marital conflicts that were repressed during the periods of exacerbation and instability now moved to the forefront.

Exacerbation

One woman described how she felt alone when her husband was medically unstable and went into rapid atrial fibrillation.

One time when he was in afib they wanted to convert him that night. I couldn’t have any one of my siblings fly in and I don’t like imposing on my friends that way. So there I am alone thinking I wish there was someone, anyone that I could just call and tell what was going on.

Another wife, whose husband was very unstable thus required numerous hospitalizations discussed how her children wanted her to make the decision whether they really needed to make the trip to the hospital, she explained:

Dad’s in the hospital again. And I’m sitting there thinking “Why aren’t you here?” “Why didn’t you come?” “Where are you?” I mean I go through that a lot, on my own. “Why didn’t you come see your dad?” “He’s okay.” Well yeah he’s okay now and I try to explain it to my kids, dad is at the hospital and this could be his last time…

During times of medical instability at home, the lack of support creates a continued stress on the spousal caregiver. “I was always taught throughout my adult years if you want something you have to ask somebody, you can’t just expect someone to do it. Well I started doing that. I started asking and I still didn’t get help”

Another caregiver explained:

When he’s not doing well, I get mad at them (her children) because they don’t come and sit with him so I can go shopping for a little bit. I have to worry about going just going to the grocery store. If I’m at the grocery store and I see an ambulance going by and it’s coming in my direction, I just like flip out. I’m ready to stop my cart and take off. I get mad because they don’t come and say, “Hey mom, why don’t you go somewhere.”

Medical Stability

Several caregivers not only had to assume new roles due to their spouse’s heart failure but also attempted to navigate their new role without further upsetting their spouse.

Things that require heavy exertion are usually the sticking points in the household because especially with the man, it’s been his domain, that’s his role to take care of those things around the house and he does not deal well with seeing me doing the heavy work like shoveling. That has always been an issue, but he knows he cannot get out to do it. And my neck hurts so badly, I have a herniated disc in my neck and I am not going to say anything to him about it cause I know it was a sticky issue to begin with I am just gonna grin and bear it.

During this time, for some caregivers, marital conflicts also came to the surface. Many spousal caregivers were willing to take over all the household chores, work extra jobs, and anything that needed to be done because the spouse was unable to contribute. However, there were numerous instances when the spouse with heart failure actually improved significantly and could now help out a little bit, but did not. This caused marital tension. One wife discussed that now that her husband was stable she needed support from him, but did not receive any:

I’ve been having a really hard time now, I probably was depressed now for a year and a half because I felt like I took care of him for 10 years and I’ve been taking care of him and now he’s better and you know I’m having little problems here and there and he’s not taking care of me and so I’m having a real hard time with it right now.

Another wife, who even during times of stability still diligently took care of her husband until he decided to go away with friends and was fine without her, was devastated when, “All these years I’ve worried myself sick and he can take care of himself!”

Spousal caregivers also expressed the need for someone to talk to, a support group, other people going through the same thing, or a therapist.

I don’t really have someone that I can really talk to. I don’t want to talk to my daughter, I don’t want to talk to my friend, I want to talk—I want to talk to someone that can help me.

Psychosocial issues for emotional and spiritual support were evident especially in those caregivers with few family members or friends available to help. In particular, the needs of caregivers who were caring for aging parents or in-laws in addition to caring for their spouse voiced concerns about their own stress levels.

One other thing we’re dealing with right now is his mother…she has cancer. My husband is the only child, so it’s all kind of on us, on me…I’m hoping I can figure out a stress management system for myself.

Physical Issues

The physical issues reported by the spousal caregivers were numerous, but during times of exacerbation and subsequent medical instability were ignored by many of the spousal caregivers. These caregivers describe being exhausted and stressed and not having their own medical issues addressed. Some of these caregivers worked full-time and still travelled daily to see their spouse in the hospital, while others juggled children and or other household activities, so did not take care of themselves. Once discharged, the caregiver was equally as stressed since many of the patients also required significant care on the part of the caregiver, including dressing changes and titration of medications such as diuretics and blood thinners. Over the course of this study, once the patient was finally medically stable, spousal caregivers would tell us they could now have their own medical issues addressed.

Exacerbation

When taking her husband home after placement of an internal cardiac defibrillator, one spouse described how she felt overwhelmed and even became physically ill at the anticipation of having to provide care to her husband at home.

I always had felt that the doctors could fix everything. They gave him pills and fixed it or did something to fix him. Well this is the first time I realized that if anything happened to him on the way home and I was driving and I was just not sure what I would do. And all of a sudden I just thought I can’t do this. I cannot do this anymore; over and over again I can’t do it anymore and I just turned the car right around and my heart was pounding and I went to the emergency room and I said. “I don’t know what’s wrong but I have to come in here.”

Another caregiver who works all week and still cared for her husband said:

Towards the end of the week I’m stressed and I need that rest on the weekend, but again this whole thing is stressful for him because of how bad he is…

Medical Stability

Several of the caregivers required medical interventions for their own health problems but did not even discuss having them taken care of until their spouse was medically stable. A female caregiver summarized her own health issues:

In fact today, I will call the doctor. I have a prolapsed bladder and it’s really bothering me lately and now that he is feeling better I want to look into having it surgically corrected.

Discussion

According to the NCP,5 comprehensive palliative care must address both the patient and family caregiver, as instrumental partners in care. Healthcare providers should not only consider these caregivers as caregivers, but also as care recipients. That is, the needs of spousal caregivers must be assessed and need-driven and anticipatory support for couples given throughout the heart failure trajectory. Our findings reveal that there are categories of needs that would be amenable to palliative care interventions that were common to all of the spousal caregivers regardless of their spouse’s progression along the heart failure trajectory: Informational, Financial, Psychosocial, and Physical. These are common needs that are reprioritized over the course of the disease trajectory. Many of the issues and unmet needs affected both the spouse with heart failure and the spousal caregiver, while some appeared to only impact the caregiver. Nonetheless, the health and well-being of the caregiver ultimately impacts the patient.

The needs expressed by the spousal caregivers in this study overlap somewhat with findings reported from other studies. For example, Pressler et al.24 report that managing personal finances, managing dietary needs, and getting information from healthcare providers were among the most difficult tasks in caregiving. Harding et al.13 report that heart failure patients and their families who were interviewed about their experience living with heart failure expressed limited knowledge about symptom management and disease progression. Likewise, the spousal caregivers in our studies also voiced a knowledge deficit about treatment options and daily management for heart failure. Some of the needs/issues identified in our studies are typically addressed with the spousal caregiver during a hospitalization. For instance, financial counselors and/or social workers may be brought in. During this time, nurses and other healthcare providers encourage caregivers to take care of themselves, telling them to eat and to go home to rest. Davidson and colleagues12 report that the immediate post-hospitalization is a vulnerable time for patients when psychosocial and existential needs go unaddressed. Our findings additionally confirm that during times of medical stability when patients and families are living “everyday” with heart failure, their needs most often go unaddressed.

Furthermore, in a study to explore the well-being of heart failure caregivers, Luttik et al.7 found that caregivers did not feel acknowledged or supported by the healthcare providers. Similarly, our findings revealed that spousal caregivers go to clinic visits and describe having their concerns “dismissed” by the health care provider because the patient is considered medically stable. Caregivers feel that they are left on their own to handle all of the care, including the navigation through complicated insurance and governmental systems, trying to get their spouse on disability, or obtain health insurance for themselves. Thus, the results of this study suggest that there is a prime window of opportunity for nurses to come along side heart failure patients and their caregivers during times of medical stability to help them deal with the stresses of living with heart failure and to help them find answers for the problems and needs that surface during this time. We assert that the aim of palliative care is to support both the patient and the caregiver throughout the experience of heart failure, not just provide episodic palliative and supportive care during times of exacerbation and hospitalization.

Implications

In summary, we agree with the NCP5 which describes palliative care as more than just attention to physical symptoms with comfort care at end of life, asserting that psychosocial concerns, spiritual concerns, cultural needs, medication management, financial concerns, and support of family goals for care are integral to the delivery of palliative care. Bekelman and colleagues2 suggest that there are potential critical junctures in the heart failure experience where palliative care interventions may be targeted, such as during hospitalization, at the time of device implantation, and heart transplantation evaluation. Our study of spousal caregivers reveals that while these are all important transitions during which palliative care interventions are helpful, there are also critical needs that surface during times of stability in living with heart failure that demand the attention of the healthcare team. Heart failure patients and their spouses have supportive care/palliative care needs that begin at the time of diagnosis, and despite the return to normal, the underlying threat of exacerbation/sudden death from heart failure is ever-present, therefore, episodic offerings of supportive/palliative care targeted during exacerbations are inadequate for this population. At every patient-healthcare professional interaction, assessment of needs and plans for supportive interventions should be undertaken. Thus, the scope of care provided by heart failure programs must expand beyond just medical management to include attention to the unmet needs of patients and caregivers in the areas of information, finance, psychosocial and physical needs. Nurses working in heart failure centers are well-positioned to develop approaches for such comprehensive assessment to occur.

Hupcey and colleagues1 purport that palliative care should be conceptualized as a philosophy of care that should be provided by all healthcare professionals, beginning at the time of diagnosis, and comprehensively anticipating and responding to the needs of patients and their families in concert with the heart failure trajectory. By anticipating and responding to the needs of patients and their caregivers, healthcare professionals can assuage many of the stressors that accompany the life threatening diagnosis of heart failure. This paper highlights several categories of needs that are amenable to a comprehensive approach to palliative care with a focus on anticipating and responding to patient and caregiver needs. Many of the needs expressed by the participants in this study would continue to go unmet with a more traditional model of palliative care that only targets physical symptoms aimed at providing comfort care at end of life. For example, helping couples to address the financial burden of illness early in the disease process may help them cope with the inevitable strain on their finances that often accompanies the heart failure experience. Likewise, keeping patients informed and educated about treatment options in terms that they can understand empowers them to make decisions that are in their best interest as a family. Encouraging and facilitating discussion of sensitive topics such as advance directives and end-of-life care during times of medical stability may also help couples to give thoughtful consideration to their preferences apart from having to face such decisions during the stress of an exacerbation.

Heart failure remains an insidious disease with an unpredictable trajectory. No two patients’ experiences will mirror the other. Nonetheless, these data reveal that there are common categories of needs that arise throughout the heart failure trajectory regardless of whether the patient is in a time of medical stability or exacerbation. Thus, heart failure patients and their caregivers need comprehensive palliative care interventions that attend to more than just physical symptoms to support them throughout the entire experience. Future research efforts must focus on developing and testing interventions in a variety of care delivery settings with heart failure patients and their caregivers to address needs that remain unmet with the traditional approaches to heart failure care. Nurses who care for heart failure patients can play a pivotal role in facilitating such research efforts and leading interdisciplinary teams to implement comprehensive palliative care interventions to ultimately improve the experience of caring for and living with heart failure.

Acknowledgments

NIH/NINR:1R15NR009976

American Heart Association: Pennsylvania/Delaware Affiliate, Grant-in-Aid Program

Contributor Information

Judith E. Hupcey, School of Nursing, The Pennsylvania State University.

Kimberly Fenstermacher, School of Nursing, The Pennsylvania State University.

Lisa Kitko, School of Nursing, The Pennsylvania State University.

Janet Fogg, School of Nursing, The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- 1.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fenstermacher K. Review article: a model of palliative care for heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009 Oct–Nov;26(5):399–404. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekelman DB, Hutt E, Masoudi FA, Kutner JS, Rumsfeld JS. Defining the role of palliative care in older adults with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2008 Apr 10;125(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fogg J. Heart failure and palliative care: Implications in practice. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2009 Jun;12(6):531–536. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Accessed December 9, 2010];WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at http://who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 5.Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson H, Ward C, Eardley A, et al. The concerns of patients under palliative care and a heart failure clinic are not being met. Palliat Med. 2001 Jul;15(4):279–286. doi: 10.1191/026921601678320269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luttik ML, Blaauwbroek A, Dijker A, Jaarsma T. Living with heart failure: partner perspectives. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007 Mar–Apr;22(2):131–137. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott LD. Caregiving and care receiving among a technologically dependent heart failure population. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2000 Dec;23(2):82–97. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, et al. Modelling services to meet the palliative care needs of chronic heart failure patients and their families: current practice in the UK. Palliat Med. 2007 Jul;21(5):385–390. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambroski CH. Hospice as an alternative model of care for older patients with end-stage heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004 Jan–Feb;19(1):76–83. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00012. quiz 84–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldred H, Gott M, Gariballa S. Advanced heart failure: impact on older patients and informal carers. J Adv Nurs. 2005 Jan;49(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson PM, Cockburn J, Newton PJ. Unmet needs following hospitalization with heart failure: implications for clinical assessment and program planning. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008 Nov–Dec;23(6):541–546. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000338927.43469.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 Aug;36(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark AM, Freydberg N, Heath SL, Savard L, McDonald M, Strain L. The potential of nursing to reduce the burden of heart failure in rural Canada: what strategies should nurses prioritize? Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;18(4):40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sebern M, Riegel B. Contributions of supportive relationships to heart failure self-care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009 Jun;8(2):97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martensson J, Dracup K, Fridlund B. Decisive situations influencing spouses’ support of patients with heart failure: a critical incident technique analysis. Heart Lung. 2001 Sep–Oct;30(5):341–350. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.116245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callahan HE. Families dealing with advanced heart failure: a challenge and an opportunity. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2003 Jul–Sep;26(3):230–243. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evangelista LS, Dracup K, Doering L, Westlake C, Fonarow GC, Hamilton M. Emotional well-being of heart failure patients and their caregivers. J Card Fail. 2002 Oct;8(5):300–305. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.128005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahoney JS. An ethnographic approach to understanding the illness experiences of patients with congestive heart failure and their family members. Heart Lung. 2001 Nov–Dec;30(6):429–436. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.119832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molloy GJ, Johnston DW, Witham MD. Family caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005 Jun;7(4):592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ. 2002 Oct 26;325(7370):929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders MM. Family caregivers need support with heart failure patients. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003 May–Jun;17(3):136–142. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hupcey JE, Fenstermacher K, Kitko L, Penrod J. Achieving medical stability: Wives’ experiences with heart failure. Clin Nurs Res. 2010 Aug;19(3):211–229. doi: 10.1177/1054773810371119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizlo I, Chubinski SD, et al. Family caregiver outcomes in heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 2009 Mar;18(2):149–159. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]