Summary

PSD-95, a multi-domain protein enriched in the postsynaptic density, influences AMPA receptor (AMPAR) content at synapses and may play a critical role in LTD. Here we molecularly dissect the effects of PSD-95 on basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic responses and LTD using several complementary approaches. Our findings suggest that N-terminal domain mediated dimerization is important for PSD-95’s effect on basal synaptic AMPAR function whereas the SH3-GK domains in its C-terminal region are also necessary for localizing PSD-95 to synapses. Using a molecular replacement approach, we identify point mutants (Q15A, E17R) of PSD-95 that increase basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic responses to the same degree as wildtype PSD-95 yet block LTD. These point mutants increase the proteolysis of PSD-95 within its N-terminal domain. Several lines of evidence indicate that the resulting C-terminal fragment of PSD-95 functions as a dominant negative by binding to one or more of the critical signaling proteins required for LTD. Together our findings demonstrate that the effects of PSD-95 on basal AMPAR synaptic responses and LTD are dissociable. The N-terminal domain of PSD-95 is required for dimerization and appropriate synaptic enrichment of PSD-95 but alone does not influence synaptic function. The C-terminal portion of PSD-95 serves a dual function. It is also required to localize PSD-95 at the synapse and as a scaffold for critical downstream signaling proteins that are required for LTD.

Introduction

Activity-dependent regulation of excitatory synaptic strength by synaptic incorporation or retrieval of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptors (AMPARs) are key mechanisms underlying several prominent forms of synaptic plasticity (Bredt and Nicoll, 2003; Collingridge et al., 2004; Malenka and Bear, 2004; Malinow and Malenka, 2002; Sheng and Kim, 2002; Shepherd and Huganir, 2007). Thus elucidating the detailed molecular processes that control AMPAR content at synapses is critical for understanding the neural substrates of various forms of developmental and experience-dependent plasticity, including learning and memory. Substantial evidences suggest that the postsynaptic density protein of 95 kDa (PSD-95; also known as synapse associated protein 90, SAP90) is one key component of the postsynaptic molecular architecture that controls synaptic AMPAR content and thereby synaptic strength. Most importantly, acute overexpression of PSD-95 causes a large enhancement of AMPAR- but not NMDAR-mediated EPSCs in hippocampal neurons (AMPAR EPSCs and NMDAR EPSCs, respectively) while acute knockdown of PSD-95 via RNAi (RNA interference) decreases AMPAR EPSCs but, in most studies, not NMDAR EPSCs (Beique and Andrade, 2003; Beique et al., 2006; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Ehrlich et al., 2007; Elias et al., 2006; Futai et al., 2007; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Schluter et al., 2006; Schnell et al., 2002).

Molecular manipulations of PSD-95 also appear to profoundly influence synaptic plasticity. Hippocampal slices prepared from mutant mice lacking PSD-95 expressed greatly enhanced NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) whereas NMDAR-dependent long-term depression (LTD) was absent (Migaud et al., 1998). Conversely, overexpression of PSD-95 occluded LTP (Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Stein et al., 2003), and decreased the threshold for LTD induction (Beique and Andrade, 2003; Stein et al., 2003). These results suggest that PSD-95 may be indispensable for NMDAR-dependent LTD of AMPAR EPSCs. However, there are several limitations to the interpretation of these results. First, manipulation of PSD-95 may influence presynaptic function (Futai et al., 2007; Migaud et al., 1998) and this in turn may influence the ability of specific induction protocols to elicit LTP or LTD. Secondly, since the molecular manipulations of PSD-95 profoundly affect basal synaptic strength, it is difficult to know whether the observed effects on LTP and LTD are secondary to this change in synaptic strength or rather because in addition to influencing AMPAR synaptic content, PSD-95 plays an independent critical role in the triggering or expression of LTD.

Two general possibilities exist for a role of PSD-95 in LTD. Based on the strong effects of manipulating PSD-95 levels on basal synaptic transmission, it has been proposed that PSD-95 may act as a “slot” protein for synaptic AMPARs (Colledge et al., 2003; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Schnell et al., 2002). In this role, PSD-95 would be a target of the signaling cascade triggered by LTD induction and a reduction of synaptic PSD-95 levels would lead to the long-term loss of synaptic AMPARs. Consistent with this hypothesis, two biochemical modifications of PSD-95, poly-ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003) and depalmitoylation (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002), have been reported to be required for the removal of synaptic PSD-95 and hence the endocytosis of AMPARs in cultured hippocampal neurons elicited by agonist application. Although the agonist-induced endocytosis of AMPARs in cultured neurons has served as a valuable model for synaptically induced LTD in slices (Carroll et al., 1999, 2001; Sheng and Kim, 2002), the mechanisms underlying endocytosis of AMPARs in culture and LTD in slices may not be identical. In addition, the direct poly-ubiquitination of PSD-95 in response to NMDAR activation has been questioned (Patrick et al., 2003) and molecular manipulations that perturb poly-ubiquitination or palmitoylation of PSD-95 may mis-locate PSD-95. Thus the disruption of agonist-induced AMPAR endocytosis caused by interfering with these biochemical modifications of PSD-95 may not be due to the disruption of its native functional properties.

Alternatively, PSD-95 may be important for LTD as a molecular scaffold that connects NMDAR-mediated calcium entry to the downstream enzymatic machinery that triggers LTD. Similar to other members of the family of synaptic membrane-associated guanylate kinase proteins (MAGUKs) PSD-95 contains multiple protein-protein interaction motifs including three consecutive N-terminal PDZ (PSD-95, discs large, zona occludens 1) domains and C-terminal Src homology 3 (SH3) and Guanylate kinase-like (GK) domains (Kim and Sheng, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2004). While the PDZ domains appear important for binding PSD-95 directly to NMDARs or indirectly to AMPARs via TARPs (Chen et al., 2000; Kornau et al., 1995; Niethammer et al., 1996; Schnell et al., 2002), the SH3 and GK domains interact with several proteins that may influence intracellular signaling cascades. Specifically, the SH3-GK domains of PSD-95 interact with A-kinase-anchoring protein 79/150 (AKAP79/150), guanylate kinase-associated protein (GKAP) and spine-associated RapGAP (SPAR) (Kim and Sheng, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2004). The binding of PSD-95 to AKAP79/150 is of particular interest because AKAP79/150 in turn binds to protein kinase A and the Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin (PP2B), both of which appear to be important for LTD (Kameyama et al., 1998; Mulkey et al., 1994). Indeed, dynamic interactions between AKAP79/150, PSD-95 family proteins and PP2B may regulate synaptic AMPAR levels in cultured neurons (Tavalin et al., 2002).

Here we use a lentivirus-mediated molecular replacement strategy (Schluter et al., 2006), which allows simultaneous RNA interference-mediated knockdown of endogenous PSD-95 and expression of mutant forms of recombinant PSD-95 in single cells, to study the molecular determinants of PSD-95 for regulating basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic strength and mediating LTD. We find that PSD-95 regulates basal synaptic AMPAR content in a manner that requires both its N-terminal domain, which mediates homomeric dimerization/multimerization necessary for synaptic enrichment of PSD-95, as well as its C-terminal domains, which are required for its localization at synapses. We then demonstrate that the role of PSD-95 in controlling basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic strength can be dissociated from its role in LTD. Analysis of a series of deletion constructs and point mutants support the hypothesis that PSD-95, via its C-terminal protein-protein interaction domains, functions as a critical signaling scaffold to couple the NMDAR-mediated rise in calcium to the intracellular signaling cascades that are required for the triggering of LTD.

Results

Regulation of Basal Synaptic Strength by PSD-95 Requires Both N- and C-terminal Domains

Previous studies have shown that acute changes in PSD-95 level affect the size of AMPAR mediated synaptic responses (Beique and Andrade, 2003; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Ehrlich et al., 2007; Elias et al., 2006; Futai et al., 2007; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Schluter et al., 2006; Schnell et al., 2002). Overexpression of deletion constructs specifically suggested that the N-terminal portion of PSD-95 containing the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains is localized to synapses (Craven et al., 1999) and alone is sufficient to mediate the increase of AMPAR EPSCs (Schnell et al., 2002). However, a similar deletion mutant is still present in the original PSD-95 knockout mice but was reported to be absent from the PSD (Migaud et al., 1998). This discrepancy raised the possibility that the presence of endogenous PSD-95 might play a role in mediating the effect of this deletion mutant on AMPAR EPSCs when overexpressed. To address this issue, we compared the effects of the N-terminal segment of PSD-95 including the first two PDZ domains (PSD-95PDZ1+2, fused to GFP) on basal synaptic transmission when overexpressed versus when expressed in the absence of detectable levels of endogenous PSD-95, which was reduced by simultaneous expression of a short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against PSD-95 (sh95) (Schluter et al., 2006). Consistent with previous studies (Schnell et al., 2002), PSD-95PDZ1+2 overexpression selectively increased AMPAR EPSCs but not NMDAR EPSCs when compared to simultaneously recorded, uninfected neighboring cells (Figure 1A). Consistent with its effects on synaptic transmission, PSD-95PDZ1+2 had a highly punctate expression pattern in dendrites when GFP fluorescence was examined by confocal microscopy (Figure 1A right panel). Surprisingly, however, when PSD-95PDZ1+2 was expressed while simultaneously reducing the level of endogenous PSD-95, using an approach we have termed “molecular replacement” (Schluter et al., 2006), AMPAR EPSCs in infected cells were reduced to a degree essentially identical to that observed with expression of sh95 alone (Figure 1B, E). This was in contrast to the dramatic effects of replacing endogenous PSD-95 with wildtype PSD-95 (Figure 1E) (Schluter et al., 2006). Furthermore, consistent with its lack of effect on basal synaptic transmission the expression pattern of PSD-95PDZ1+2, when expressed in the absence of detectable endogenous PSD-95, is diffuse, not punctuate, in dendrites (Figure 1B right panel).

Figure 1.

C-terminal Domains of PSD-95 are Required for Its Effects on Basal AMPAR EPSCs

(A) Amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs (left panel, uninfected −34.9 ± 3.5 pA, infected, −59.6 ± 5.7 pA, p < 0.001) and NMDAR EPSCs (middle panel, uninfected 50.7 ± 5.7 pA, infected, 59.1 ± 5.9 pA, p > 0.05) of neurons expressing PSD-95PDZ1+2::GFP are plotted against those of simultaneously recorded uninfected neighboring neurons. (In this and all subsequent panels: gray symbols represent single pairs of recordings; black symbols show mean ± SEM; p values were calculated with a paired Student’s t-test comparing absolute values of paired recordings). Inserts in each panel show sample averaged traces (gray traces, infected neurons; black traces, uninfected neighboring neurons, scale bars, 50 pA/20 ms for AMPAR EPSCs; 50 pA/50 ms for NMDAR EPSCs). Right panels show confocal images of GFP fluorescence (scale bars, 20 μm, left panel, and 2 μm, right panel).

(B) Amplitudes of AMPAR EPSCs (uninfected, −60.1 ± 5.5 pA, infected, −30.6 ± 3.8 pA, p < 0.001) and NMDAR EPSCs (uninfected, 64.7 ± 9.7 pA, infected, 49.6 ± 7.4 pA, p < 0.01) of neurons expressing sh95 + PSD-95PDZ1+2::GFP and uninfected neighboring neurons. Right panels show confocal images of GFP fluorescence (scale bars, 20 μm, left panel, and 2 μm, right panel).

(C) Amplitudes of AMPAR EPSCs (uninfected, −42.6 ± 4.5 pA, infected, −69.1 ± 5.5 pA, p < 0.001) and NMDAR EPSCs (uninfected, 36.0 ± 5.6 pA, infected, 34.8 ± 3.4 pA, p > 0.05) of neurons expressing PSD-95ΔSH3-GK::GFP and uninfected neighboring neurons.

(D) Amplitudes of AMPAR EPSCs (uninfected, −62.0 ± 5.5 pA, infected, −30.3 ± 3.0 pA, p < 0.001) and NMDAR EPSCs (uninfected, 87.8 ± 10.5 pA, infected, 72.0 ± 9.1 pA, p < 0.01) of neurons expressing sh95 + PSD-95ΔSH3-GK-IRES-GFP and uninfected neighboring neurons.

(E) Summary (mean ± SEM) of effects of expressing various forms of PSD-95 alone or with sh95 on AMPAR EPSCs calculated as the averaged ratios obtained from pairs of infected and uninfected neighboring neurons (2.17 ± 0.37, 2.35 ± 0.35, 2.35 ± 0.31, 2.72 ± 0.25, 0.51 ± 0.10, 0.56 ± 0.07, 0.59 ± 0.03, respectively, numbers of pairs analyzed are indicated in the bar; n.s. indicates p > 0.05; *** p < 0.001 using an ANOVA Tukey HSD t-test).

(F). Summary of effects of same manipulations as in (E) on NMDAR EPSCs (1.21 ± 0.11, 1.36 ± 0.12, 1.23 ± 0.18, 1.20 ± 0.15, 0.80 ± 0.04, 0.85 ± 0.06, 0.88 ± 0.04, respectively, n.s. indicates p > 0.05).

A deletion mutant lacking the SH3 and GK domains (PSD-95ΔSH3-GK) behaved similarly to PSD-95PDZ1+2. Whereas overexpression of PSD-95ΔSH3-GK increased AMPAR EPSCs, expression of PSD-95ΔSH3-GK with greatly reduced endogenous PSD-95 did not rescue the decrease of AMPAR EPSCs caused by sh95 (Figures 1C and D). The dramatic differences between the synaptic effects of these two PSD-95 deletion constructs when overexpressed in the presence or virtual absence of endogenous PSD-95 are summarized in Figures 1E and F. Importantly, whereas overexpression of wildtype PSD-95 increased AMPAR EPSCs to an identical extent under both conditions, replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with C-terminal domain deletion mutants could not rescue the decrease of AMPAR EPSCs caused by the large reduction of endogenous PSD-95. These data suggest that the C-terminal region of PSD-95 containing the SH3-GK domains is important for the localization of PSD-95 at the PSD and hence for the effect of PSD-95 on AMPAR EPSCs. In addition, these results suggest that in the absence of adequate levels of endogenous PSD-95, N-terminal portions of PSD-95 either cannot target to synapses appropriately or are not maintained in the PSD at a location that allows them to influence synaptic AMPAR levels.

N-terminal Domain of PSD-95 is Required for Dimerization

Because of the requirement of the full-length PSD-95 for the effects of PSD-95 C-terminal domain deletion mutants on basal synaptic AMPAR function, we hypothesized that homotypic interactions of the mutants with endogenous PSD-95 are likely critical for targeting and stabilizing their localization at synapses. The importance of PSD-95 N-terminal domain homotypic interactions have been studied previously but the results are confusing with some papers reporting an important role for these interactions in mediating the dimerization of PSD-95 while others suggest that the important function of the N-terminal domain is solely because of its palmitoylation (Figure 2A) (Christopherson et al., 2003; Hsueh et al., 1997; Hsueh and Sheng, 1999; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Topinka and Bredt, 1998). To examine the role of the PSD-95 N-terminal domain in dimerization, we co-expressed untagged PSD-95 with GFP tagged PSD-95 or GFP tagged mutants in HEK293 cells. We then immunoprecipitated the cell lysates using GFP antibody, and immunoblotted with PSD-95 antibody. Consistent with the electrophysiological results, both the full length PSD-95 and PSD-95PDZ1+2 mutant can co-immunprecipitate the untagged PSD-95 (Figure 2B). In fact, the N-terminal 64 amino acids of PSD-95 fused to GFP were sufficient to co-immunoprecipitate full-length PSD-95 (Figure 2B) as well as a peptide containing only the N-terminal 32 amino acids (data not shown), indicating an N-terminal domain homotypic interaction.

Figure 2.

N-terminal Mediated Interactiona are Required for PSD-95 to Affect Basal AMPAR EPSCs

(A) Conserved motif in the N-terminus of vertebrate PSD-95.

(B) PSD-95 can dimerize through its N-terminus. Western blot of input (top panel) and proteins immnunoprecipitated using GFP antibody (bottom panel) from HEK cells transfected with the indicated constructs and blotted with PSD-95 antibody.

(C) Overexpression of PSD-95ΔPEST::GFP does not affect basal AMPAR EPSCs (uninfected, −52.0 ± 6.5 pA, infected, −58.4 ± 7.6 pA, p > 0.05, n=42 pairs) nor NMDAR EPSCs (uninfected, 67.5 ± 7.3 pA, infected, 62.7 ± 6.9 pA, p > 0.05, n=20 pairs) (scale bars, 50 pA/20 ms for AMPAR EPSCs; 50 pA/50 ms for NMDAR EPSCs).

(D) Confocal images of GFP from neurons infected with PSD-95ΔPEST::GFP and PSD-95::GFP (scale bars, 20 μm, top panels and 2 μm, bottom panels).

To further test the importance of the N-terminal domain of PSD-95 for its dimerization we examined two previously described PSD-95 mutants, PSD-95ΔPEST, which lacks a motif that has been suggested to be important for PSD-95 poly-ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003) and PSD-95C3,5S, which cannot be palmitoylated (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). Neither one of these N-terminal domain mutant constructs was capable of co-immunoprecipitating the full-length PSD-95, further supporting a role for an N-terminal domain homotypic interaction (Figure 2B).

Previous studies have reported that overexpression of PSD-95C3,5S has no effect on AMPAR EPSCs, likely because it is not maintained at synapses (Schnell et al., 2002). To determine whether PSD-95ΔPEST, in terms of its functional effects, behaved like PSD-95C3,5S or wildtype PSD-95, we measured AMPAR EPSCs in cells in which it had been overexpressed and found that it had no detectable effect (Figure 2C). Furthermore, confocal microscopy revealed that PSD-95ΔPEST did not exhibit the highly punctuate expression pattern in dendrites that is a hallmark of wildtype PSD-95 (Figure 2D). These results are consistent with the suggestion that the synaptic effects of PSD-95 require its dimerization or multimerization via its N-terminal domain. Specifically, overexpression of mutant forms of PSD-95 that were able to dimerize/multimerize with full length PSD-95 clearly enhanced basal AMPAR EPSCs whereas N-terminal domain mutations that prevented dimerization did not affect basal synaptic responses. Together with the previous results, these data also suggest that both the N- and C-terminal domains of PSD-95 are important for mediating its effects on AMPAR EPSCs. While PSD-95 can dimerize or multimerize through its N-terminal domain and the PDZ domains are important for interacting with AMPARs and NMDARs, we suggest that at least one C-terminal SH3-GK domain is important for localizing a given set of interacting PSD-95 proteins within the PSD, potentially by anchoring it within the postsynaptic protein network.

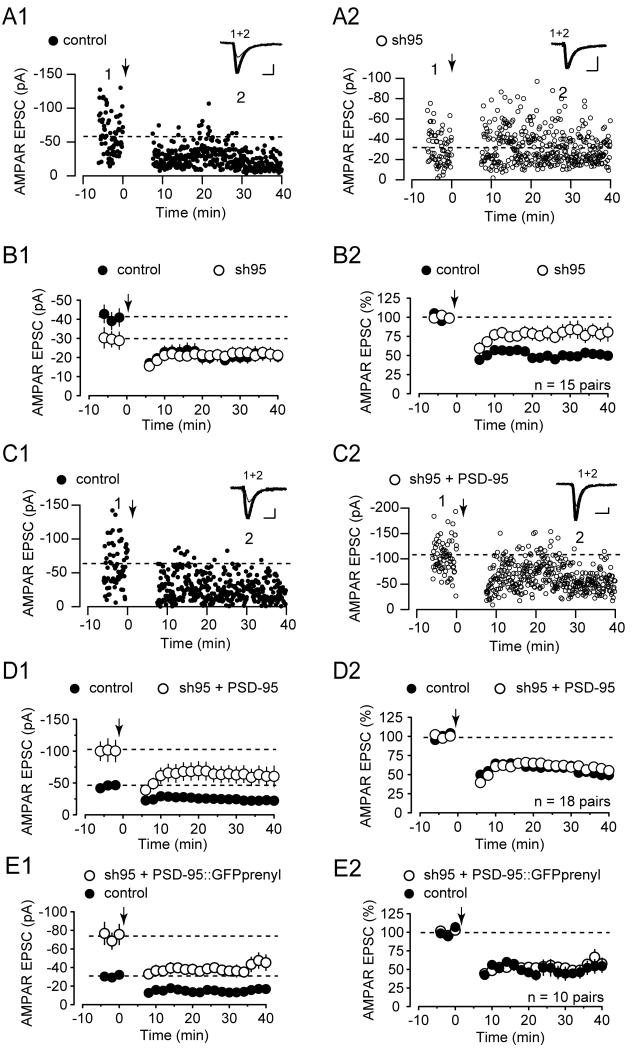

Acute Knockdown of PSD-95 Impairs LTD

Previous studies using knockout mice lacking synaptic PSD-95 reported the absence of LTD (Migaud et al., 1998). However, PSD-95 was absent throughout development in these experiments and changes in short-term synaptic plasticity were observed, both of which might have effected the generation of LTD. Here, we examined LTD after acute knockdown of PSD-95 using lentivirus-mediated shRNA, a manipulation that had no detectable effects on presynaptic function (Elias et al., 2006; Schluter et al., 2006) and which minimizes the possibility of developmental compensations. When compared to the LTD in simultaneously recorded control cells, acute knockdown of PSD-95 greatly reduced the magnitude of LTD (Figure 3A and B; control 50 ±10% of baseline, sh95 80 ± 8%, n=15). One simple explanation for this reduction in LTD magnitude caused by sh95 is that it is due to the reduction in basal synaptic strength combined with some sort of floor effect below which AMPAR EPSCs cannot be further reduced. Alternatively, PSD-95 might play a critical role in mediating LTD independent of its effects on basal synaptic strength. In this case, the incomplete block of LTD can be attributed to some functional redundancy with other MAGUK family members (Elias et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

Reduction of LTD by Acute Knockdown of PSD-95 is Rescued by Replacement with Wildtype or Prenylated PSD-95

(A) Sample experiment showing simultaneous recording of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from an uninfected control cell (A1) and an sh95 infected neighboring cell (A2). Downward arrow in this and all subsequent figures indicates time at which LTD induction protocol was given. In this and all subsequent figures, traces above the graph show averaged EPSCs (20–40 consecutive responses) taken at the times indicated by the numbers on the graph (thick traces, averaged EPSCs from baseline; thin traces, averaged EPSCs after LTD induction; scale bars, 20 pA/20 ms).

(B1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 infected cells ( n = 15 pairs). In this and all subsequent summary graphs, points represent mean ± s.e.m. (B2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 15 pairs).

(C) Sample experiment illustrating LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from an uninfected control cell (C1) and an sh95+PSD-95::GFP infected neighboring cell (C2) recorded simultaneously.

(D1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95+PSD-95::GFP infected cells (n = 18 pairs).

(D2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95+PSD-95::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 18 pairs).

(E1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95::GFPprenyl infected cells ( n = 10 pairs).

(E2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95::GFPprenyl infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 10 pairs).

To distinguish these possibilities, a dissociation of the role of PSD-95 in regulating basal synaptic transmission and LTD is required. To determine whether this could be achieved, we examined the synaptic effects of replacing endogenous PSD-95 with a number of different PSD-95 mutant constructs, focusing on mutations in the N-terminal domain. Before testing mutants, however, it was important to confirm that replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with recombinant wildtype PSD-95 could rescue the deficit in LTD. As expected, co-expression of sh95 with wildtype PSD-95 enhanced basal synaptic strength (Schluter et al., 2006) and restored LTD to normal (Figure 3C and D).

Previous studies have suggested that N-terminal domain modifications of PSD-95, specifically its poly-ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003) and depalmitoylation (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002) are important for agonist-induced endocytosis of AMPARs in cultured neurons. It was therefore of interest to examine the effects of the mutant forms of PSD-95 used in these studies on synaptically evoked LTD. However, PSD-95ΔPEST, the mutant that was reported to block poly-ubiquitination, was not targeted to synapses normally and did not have an effect on basal AMPAR EPSCs (Figure 2C and D). Therefore, we did not examine its effects on LTD. We did examine PSD-95 fused to GFP containing a prenylation signal peptide. This lipid modification has been shown to confer constitutive membrane binding to PSD-95 and thus prevent its membrane detachment (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). Importantly, it was found to impair agonist-induced endocytosis of AMPARs (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). Using the molecular replacement approach, this construct rescued basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission similar to wildtype PSD-95::GFP (Figure 3E1). However, it also rescued LTD (Figure 3E1 and E2) suggesting that detachment of PSD-95 from the plasma membrane is not required for synaptically-evoked LTD.

N-terminal Domain Point Mutants Dissociate the Effects of PSD-95 on Basal Transmission and LTD

Although examining N-terminal domain mutant forms of PSD-95 that had been reported to affect AMPAR endocytosis in culture did not prove useful in dissecting the role of PSD-95 in LTD, we next pursued the possibility that poly-ubiquitination of PSD-95 was required for this form of synaptic plasticity. Based on the highly conserved PEST motif (Figure 2A), we reasoned that changing the negatively charged glutamate at residue 17 to a positively charged arginine (E17R mutation) might disrupt the PEST function that was suggested to be required for PSD-95 poly-ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003; Rechsteiner and Rogers, 1996). As a control construct, we generated a more conservative glutamine to alanine mutation at residue 15 (Q15A mutation). Using the molecular replacement strategy to examine the effects of these point mutants on basal AMPAR EPSCs revealed that they rescued the decrease in synaptic strength caused by sh95 to the same degree as wildtype PSD-95 (Figure 4A). These results demonstrate that these PSD-95 point mutants traffic to synapses normally and are able to fulfill the normal function of PSD-95 in regulating basal synaptic strength. Surprisingly, however, LTD was blocked in cells expressing either point mutant (Figure 4B-E), a result demonstrating that the effects of PSD-95 on basal AMPAR EPSCs and LTD are dissociable and therefore must involve distinct protein-protein interactions.

Figure 4.

Replacement of Endogenous PSD-95 with E17R or Q15A Point Mutants Rescues Basal AMPAR EPSCs Yet Blocks LTD

(A) Amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs of neurons expressing sh95 + PSD-95E17R::GFP (left panel, uninfected −21.7 ±3.0 pA; infected −62.5 ±7.7 pA; p < 0.001) and sh95 + PSD-95Q15A::GFP (middle panel, uninfected −40.4 ±3.8 pA; infected −135.1 ± 14.0 pA; p < 0.001) are plotted against those of simultaneously recorded uninfected neighboring neurons. Right panel shows summary of effects on AMPAR EPSCs of expressing sh95 + PSD-95::GFP, sh95 + PSD-95E17R::GFP, and sh95 + PSD-95Q15A::GFP (2.72 ± 0.25, 3.77 ± 0.66, 3.34 ± 0.34, n.s. indicates p > 0.05).

(B) Sample experiment illustrating LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from an uninfected control cell (B1) and an sh95 + PSD-95E17R::GFP infected neighboring cell (B2) recorded simultaneously.

(C1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95E17R::GFP infected cells (n = 15 pairs).

(C2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95E17R::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 15 pairs).

(D) Sample experiment illustrating LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from an uninfected control cell (D1) and an sh95+PSD-95Q15A::GFP infected neighboring cell (D2) recorded simultaneously.

(E1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95+PSD-95Q15A::GFP infected cells (n = 12 pairs).

(E2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95+PSD-95Q15A::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 12 pairs).

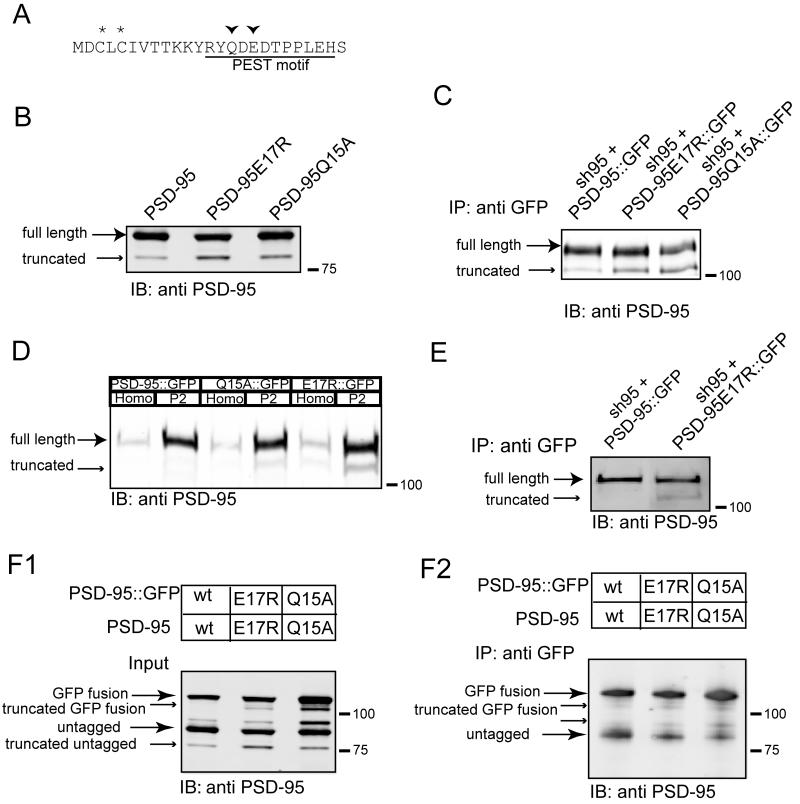

Truncation of PSD-95 Blocks LTD

Because these point mutants were generated to test the role of PSD-95 poly-ubiquitination in LTD, we examined whether they affected this biochemical modification of PSD-95 by expressing them in HEK293 cells with HA-tagged ubiquitin. Both point mutants showed ubiquitination patterns essentially identical to that of wildtype PSD-95 (data not shown). However, both point mutants (Figure 5A) exhibited an increased amount of PSD-95 with an increased electrophoretic mobility, when compared to wildtype PSD-95 (Figure 5B). To determine whether the generation of the smaller form of PSD-95 is an intrinsic property of PSD-95 processing in neurons, we infected dissociated cortical cultures with molecular replacement viruses that expressed either wildtype PSD-95 or one of the two point mutants, all tagged at the C-terminus with GFP. Similar to the results in HEK293 cells, the N-terminal domain point mutations increased the production of the smaller PSD-95 (Figure 5C). This additional PSD-95 band appears to be an N-terminal domain truncated form of PSD-95 as it has a smaller molecular weight and can be immunoprecipitated by a GFP antibody but is not recognized by an antibody directed against the N-terminal domain of PSD-95 (Schluter et al., 2006). Moreover, the truncated product of PSD-95 was present in a crude synaptosomal P2 fraction prepared from the infected neuron cultures (Figure 5D) and an increase in its production was also observed when slice cultures were infected with replacement viruses expressing the E17R mutant versus wildtype PSD-95 (Figure 5E). An additional, lower molecular weight truncation product was also apparent when wildtype PSD-95 or the point mutants were expressed in HEK293 cells (Figure 5F1). This band has been observed previously (Colledge et al., 2003; Morabito et al., 2004; Sans et al., 2000) and its relative amount was not affected by the E17R and Q15A point mutants that blocked LTD.

Figure 5.

The E17R and Q15A Point Mutants in the N-terminus of PSD-95 Increases Its Truncation

(A) Positions of the two point mutations are shown.

(B) In HEK293 cells E17R and Q15A mutants show increased amounts of truncated PSD-95 compared to wildtype PSD-95.

(C) The increased truncation of E17R and Q15A mutants is present in neurons infected with the indicated replacement viruses.

(D) The truncated form of PSD-95 is present in a crude, synaptosomal P2 fraction prepared from cortical neuron cultures infected with the indicated replacement constructs.

(E) The increased truncation of the E17R mutant is present in hippocampal slice cultures infected with the indicated replacement viruses.

(F) The E17R and Q15A mutants dimerize, but the truncated PSD-95 does not. Western blot of input (F1) and proteins immnunoprecipitated with GFP-antibody (F2) from HEK cells transfected with the indicated constructs.

Because the N-terminal region of PSD-95 is important for mediating homomeric interactions that are critical for PSD-95 to exert its effects on synaptic function, we tested whether these two point mutants influence PSD-95 dimerization by co-expressing the mutant forms of GFP-tagged PSD-95 with untagged PSD-95 and performing co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Similar to wildtype PSD-95, both of the point mutants co-immunoprecipitated full length PSD-95 (Figure 5F). However, the untagged truncation products, which were readily detected in the cell lysate (Figure 5F1), could not be detected in the GFP antibody precipitated material (Figure 5F2). These results provide further evidence that the truncation of PSD-95 caused by the E17R and Q15A point mutations results in the loss of its N-terminal region, which is critical for normal dimerization/multimerization.

Since the point mutants had the same effect on basal synaptic strength as wildtype PSD-95 and our previous results indicated that N-terminal domain mediated dimerization is important for this synaptic function of PSD-95, we hypothesized that the block of LTD by expression of these mutants was due to a dominant negative effect of the truncated fragment of PSD-95. As an initial test of this prediction we overexpressed PSD-95E17R or PSD95Q15A with the expectation that truncation of these recombinant proteins will still occur and inhibit LTD. Indeed, expression of these PSD-95 mutants significantly increased basal AMPAR EPSCs while simultaneously blocking LTD (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Over-expression of E17R or Q15A Mutants Blocks LTD

(A1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95E17R::GFP infected cells (n = 17 pairs).

(A2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95E17R::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell (n = 17 pairs).

(B1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95Q15A::GFP infected cells (n = 13 pairs).

(B2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95Q15A::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 13 pairs).

To more narrowly define the site in PSD-95 at which its truncation occurs, we made two deletions in the N-terminal region, amino acid residues 33-53 and 45-64. While deletion of residues 33-53 did not prevent the truncation of PSD-95 (data not shown), deletion of residues 45-64 in the PSD-95Q15A mutant (PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64) completely blocked its truncation (Figure 7A and B) suggesting that the proteolysis occurred in the region of PSD-95 between residues 53 and 64. Consistent with this conclusion, co-immunoprecipitation experiments in HEK293 cells revealed that this construct still interacted normally with full length PSD-95 (Figure 7C). Most importantly, replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64 rescued basal AMPAR EPSCs to a level comparable to wildtype PSD-95 but LTD was normal indicating that the block of LTD caused by the Q15A mutation no longer occurred (Figure 7D and E). Together with the findings from the overexpression experiments, these results suggest that the blockade of LTD by the PSD-95 N-terminal domain point mutants is due to their increased truncation.

Figure 7.

Deletion of Amino Acid Residues 45-64 Prevents the Increased Truncation of the PSD-95Q15A Mutant and Rescues LTD

(A) Amino acid sequence of the N-terminal domain of PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64, showing the position of the deletion.

(B) Western blot showing that in HEK293 cells PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64 is not truncated.

(C) PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64 dimerizes. Western blot of input (upper panel) and proteins immnunoprecipitated with GFP antibody (lower panel) from HEK cells transfected with the indicated constructs.

(D) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95 Q15AΔ45-64::GFP infected cells (n = 11 pairs).

(E) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95 Q15AΔ45-64::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell (n = 11 pairs).

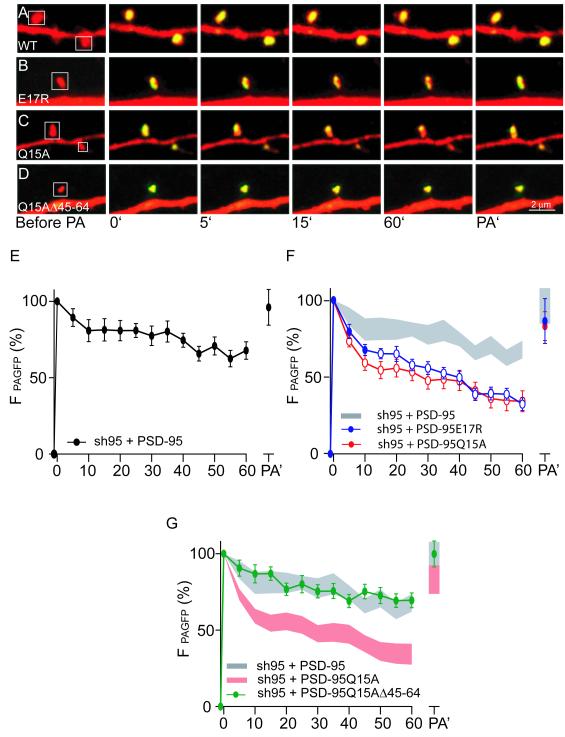

Increased Truncation of PSD-95 Q15A and E17R Mutants Increases Their Mobility in Spines

We have provided evidence that both the C- and N-terminal domains of PSD-95 are important for its synaptic targeting and stabilization at synapses and that N-terminal domain mediated dimerization/multimerizaton is important for its effects on basal AMPAR EPSCs. If our conclusion that the Q15A and E17R point mutants increase the proteolysis of PSD-95 at synapses and thereby the generation of C-terminal fragments is correct, we would expect these point mutants to be less stable at synapses than wildtype PSD-95. To test this prediction, we examined the basal mobility of PSD-95 at synapses using time-lapse imaging of wildtype and mutant forms of PSD-95 fused to photoactivatable GFP (PAGFP) at their C-termini (Gray et al., 2006; Patterson and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2002). Expression of wildtype PSD-95 using the molecular replacement strategy revealed that it was relatively stable within individual dendritic spines with ~75% of the original spine fluorescence being retained 60 minutes after photoactivation (Fig. 8A, E). (dsRed was also expressed so that spines on the transfected cells were easily identifiable.) The retained pool of PSD-95 presumably reflects protein that is anchored within the spine and therefore limited in its ability to diffuse away from the site of photoactivation. After 60 minutes of imaging, a second photoactviation pulse (PA’) returned spine PAGFP fluorescence to its original value (Fig. 8A, E). This suggests that the total amount of wildtype PSD-95 within the spine remains relatively constant likely due to an exchange of a freely diffusing pool of PSD-95 with the more stable spine pool.

Figure 8.

The E17R and Q15A Point Mutants Show Increased Diffusion Out of Spines Due to Their Truncation

(A-D) Sample images of spines from neurons expressing dsRed and the indicated forms of PSD-95 fused to photoactivatable GFP. At time 0′ GFP was photoactivated and changes in fluorescence intensity were monitored at the indicated times. A second photoactivation was performed after 60 min of imaging (PA’).

(E) Summary graph of loss of GFP fluorescence from individual spines from cells expressing sh95 and wildtype PSD-95 (n=17/5 spines/cells).

(F) Summary graphs of loss of GFP fluorescence from individual spines from cells expressing sh95 with PSD-95E17R (n=25/5 spines/cells) or PSD-95Q15A (n=23/5 spines/cells). Open circles indicate time points at which the values are statistically different (p<0.05) compared to the corresponding timepoint in wildtype cells. For comparison, the summary graph of wildtype PSD-95 (mean ± SEM) is shown in the gray shaded region.

(G) Summary graph of loss of GFP fluorescence from individual spines from cells expressing sh95 with PSD-9Q15A5Δ45-64 (n=27/5 spines/cells). For comparison, the summary graphs of wildtype PSD-95 (gray) and Q15A PSD-95 (pink) are also shown.

The Q15A and E17R PSD-95 point mutants within spines were dramatically less stable in that only ~40% of the original spine fluorescence was present at 60 minutes after photoactivation (Fig. 8B, C, F). This is likely due to the generation of C-terminal fragments fused to the GFP that are no longer able to dimerize and thus are free to diffuse out of the PSD and spine. To test this hypothesis, we examined the deletion mutant that prevents the proteolysis of Q15A PSD-95 (PSD-95Q15AΔ45-64) and found that it behaved identically to wildtype PSD-95 (Fig. 8D, G). The increased rate of movement of the photoactivated Q15A and E17R mutants out of the spines does not reflect a net loss of spine PSD-95 but rather an increase in the exchange of PSD-95 within spines as a second photoactivation pulse returned GFP fluorescence to its original values. Together with previous results, these imaging experiments show that there is a direct correlation between the increase in truncation of PSD-95, the increase rate of dissociation of PSD-95 from the stable spine pool, and the block of LTD.

LTD is Blocked by The C-terminal Fragment of PSD-95

The results thus far suggest that the fragments generated by the truncation of PSD-95 play a dominant negative role in blocking LTD. Because the C-terminal fragment contains protein-protein interaction motifs including the SH3 and GK domains, which interact with proteins that are part of downstream signaling complexes such as AKAP, we predicted that the C-terminal fragment of the truncated PSD-95 functioned as a dominant negative inhibitor of LTD. An apparently straightforward manipulation to test this hypothesis is to overexpress the C-terminal fragment of PSD-95 alone and determine whether it impairs LTD. However, the fact that mutations in its N-terminal domain prevented PSD-95 from being targeted to synapses normally and having any effect on basal AMPAR EPSCs led us to predict that a form of PSD-95 lacking its N-terminal domain also would not be targeted to synapses normally. Consistent with this prediction, PSD-95 lacking its N-terminal 53 amino acids (PSD-95Δ2-53) did not display a highly punctuate expression pattern when examined with confocal microscopy (data not shown). Overexpression of PSD-95Δ2-53 also did not affect basal AMPAR EPSCs (n=12 pairs; uninfected cells −38.8 ± 7.1 pA; infected cells −39.7 ±5.6 pA) nor did it impair LTD (n=6, 59 ± 8% of baseline).

Because PSD-95 lacking its N-terminal domain was not targeted to synapses normally and did not affect LTD, we could not use it to probe which specific portions of the C-terminal domain were required for blocking LTD. Instead, we made mutations in the C-terminal domain of PSD-95Q15A, which we had already established blocked LTD presumably because after being targeted to synapses normally it was proteolyzed to produce a dominant negative C-terminal fragment. To determine whether the SH3-GK domains in the truncated C-terminal portion of PSD-95 were required for the block of LTD, we deleted them from the PSD-95Q15A mutant (PSD-95Q15AΔSH3-GK) as well as from wildtype PSD-95 (PSD-95ΔSH3-GK). If the N-terminal fragment of truncated PSD-95 was responsible for inhibiting LTD, LTD should still be blocked by PSD-95Q15AΔSH3-GK. However, if the C-terminal fragment containing SH3-GK domains is the critical LTD inhibitor, LTD will be unaffected. As expected from previous results, overexpression of the wildtype deletion construct (PSD-95ΔSH3-GK) increased basal AMPAR EPSCs and had no effect on LTD, presumably because the SH3-GK domains of endogenous PSD-95 could still subserve their normal functions (Figure 9A). Expression of PSD-95Q15AΔSH3-GK had the same effects (Figure 9B); it increased basal synaptic transmission and in contrast to overexpression of PSD-95Q15A (Fig. 6, it did not impair LTD. This result indicates that the C-terminal portion of the truncated full-length PSD-95 must contain the SH3-GK domains to inhibit LTD.

Figure 9.

The Block of LTD by Q15A PSD-95 Requires C-terminal Domain Interactions

(A1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95ΔSH3-GK::GFP infected cells (n = 12 pairs).

(A2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95ΔSH3-GK::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 12 pairs).

(B1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95Q15AΔSH3-GK::GFP infected cells (n = 11 pairs).

(B2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and PSD-95Q15AΔSH3-GK::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell. (n = 11 pairs).

(C1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95L460P::GFP infected cells (n = 10 pairs).

(C2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from pairs of uninfected and sh95 + PSD-95L460P::GFP infected cells, normalized to the baseline responses of each cell (n = 10 pairs).

(D1) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from uninfected (n=8) and PSD-95Q15AL460P::GFP infected cells (n = 11). Data includes 5 pairs of simultaneously recorded uninfected and infected cells, and additional cells recorded individually from slice cultures injected with lentiviruses expressing PSD-95Q15AL460P::GFP.

(D2) Summary graph of LTD of AMPAR EPSCs from uninfected (n=8) and PSD-95Q15AL460P::GFP infected cells (n = 11), normalized to the baseline responses of each cell.

To further narrow down the site in the C-terminal domain of PSD-95 that is crucial for mediating LTD, we tested an additional point mutant in the SH3 domain, L460P. In the Drosophila homolog Dlg this point mutation exhibits a severe phenotype (Woods et al., 1996) and biochemical studies suggest that it disrupts the interaction of the PSD-95 SH3 domain with AKAP79/150 but not the interaction of PSD-95 with GKAP (Colledge et al., 2000; McGee and Bredt, 1999). Replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with PSD-95L460P still clearly enhanced basal AMPAR EPSCs while LTD was dramatically reduced (Fig. 9C). However, when this point mutation was added to the Q15A point mutant and overexpressed, (PSD-95Q15AL460P), it behaved like PSD-95Q15ΔSH3-GK, not like PSD-95Q15A; it enhanced basal AMPAR EPSCs and had no effect on LTD (Fig. 9D). These results provide further evidence that the C-terminal portion of the truncated full-length PSD-95 inhibits LTD and suggest that this occurs because of the disruption of PSD-95’s interactions with downstream signaling proteins that are required for LTD such as AKAP79/150.

Discussion

The general acceptance that activity-dependent trafficking of AMPARs into and away from synapses is important for many forms of synaptic and experience-dependent plasticity (Bredt and Nicoll, 2003; Collingridge et al., 2004; Malenka and Bear, 2004; Malinow and Malenka, 2002; Sheng and Kim, 2002; Shepherd and Huganir, 2006) has generated great interest in elucidating the detailed molecular mechanisms by which AMPAR content at synapses is controlled. PSD-95, a member of the MAGUK family of synapse associated proteins, has received great attention in this context as a putative synaptic scaffold protein which functions to “tether” AMPARs at the appropriate site within the PSD (Bredt and Nicoll, 2003; Kim and Sheng, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2004; Shepherd and Huganir, 2007). Based on a variety of approaches including overexpression of wildtype and mutant forms of PSD-95, shRNA-mediated knockdown of PSD-95, and genetic deletion of PSD-95, a model has evolved suggesting that PSD-95 (as well as certain other subfamily members) indirectly binds to AMPARs via interactions between its first two PDZ domains and one of the AMPAR accessory proteins termed TARPs (Chen et al., 2000; Nicoll et al., 2006; Schnell et al., 2002). PSD-95 has also been suggested to play an important role in NMDAR-dependent forms of LTP and LTD (Ehrlich et al., 2007; Migaud et al., 1998), although the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying this putative function have not been defined. Indeed, it has remained unclear whether any influence that PSD-95 has on LTP or LTD is entirely due to its effects on regulating AMPAR content at synapses and/or some additional role as a scaffold for downstream signaling complexes. Furthermore, many of the elegant biochemical and cell biological properties of PSD-95 that have been reported have not been examined for their relevance to synaptic function.

Here we have used a molecular replacement strategy combined with a standard overexpression approach to further define the molecular properties of PSD-95 that are responsible for its roles in regulating basal AMPAR mediated synaptic transmission and LTD. We present evidence that N-terminal domain mediated homomeric interactions, presumably dimerization or multimerization, are critical for the regulation of basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. Surprisingly, in contrast to previous reports, we also demonstrate that the PSD-95 C-terminal domain, in particular the SH3-GK domain, is also required for this function of PSD-95, likely because it is crucial for localizing PSD-95 to synapses. Most importantly, we demonstrate that the role of PSD-95 in regulating synaptic AMPAR function and LTD can be molecularly dissociated. Single amino acid point mutations in its N-terminal domain allow PSD-95 to affect basal synaptic strength in a manner identical to wildtype PSD-95 yet block LTD (Figure 10A). We present evidence that the blockade of LTD is due to the production of a C-terminal fragment of PSD-95 caused by increased proteolysis in the N-terminal region of the PSD-95 point mutants. We suggest that the PSD-95 C-terminal fragment plays a dominant role in blocking LTD by interfering with the binding of critical downstream signaling complexes (Figure 10A, B). Together our results are consistent with the general idea that PSD-95 is an important multi-functional protein within the PSD. Independent of its role in tethering AMPARs at the PSD, it is required for LTD likely because of critical C-terminal SH3-GK domain protein interactions. Our results specifically implicate PSD-95 and AKAP79/150 interactions as being particularly important for LTD.

Figure 10.

Summary of the Effect of PSD-95 Manipulations on Basal Transmission and LTD

(A) Summary of the effects of PSD-95 manipulations on LTD. Percentage of the baseline response at 35-40 mins after LTD induction is plotted. Open bars, infected cells; gray bars, uninfected cells.

(B) Left panel: model for the role of PSD-95 in basal synaptic AMPAR function. Left side of spine shows the normal condition with endogenous PSD-95 present. Right side shows the consequences of overexpressing PSD-95PDZ1+2, which can interact with endogenous PSD-95 and recruit additional AMPARs. Replacing endogenous PSD-95 with PSD-95PDZ1+2 or expressing PSD-95C3,5S or PSD-95ΔPEST leaves these proteins outside the spine because they cannot dimerize with endogenous PSD-95. (Whether PSD-95ΔPEST is palmitoylated is not known.) Right panel: model for the role of PSD-95 as a signaling scaffold for LTD. Left side of spine shows the normal condition in which PSD-95 interacts with a complex of signaling proteins that is activated by NMDAR-mediated influx of calcium (red arrow) during LTD induction. Right side shows truncated PSD-95 interacting with the signaling complex away from the NMDAR such that it cannot be activated by calcium.

The Role of PSD-95 in Basal AMPAR Synaptic Function

It is generally accepted that AMPARs interact with PSD-95 via TARPs and that these interactions are important for the synaptic localization and function of AMPARs (Chen et al., 2000; Nicoll et al., 2006; Schnell et al., 2002). Based on overexpression studies, it was determined that the minimum requirements for PSD-95 to influence synaptic AMPAR function were its N-terminal palmitoylation, which appears to be required for its synaptic targeting (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002) and its first two PDZ domains, which are required to interact with TARPS (Schnell et al., 2002). However, using an approach that allows replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with mutant forms of PSD-95, we found that forms of PSD-95 lacking its C-terminal domain (PSD-95PDZ1+2 as well as PSD-95ΔSH3-GK) were unable to influence basal AMPAR EPSCs. Importantly, when overexpressed, these constructs clearly enhanced basal synaptic strength in a manner similar to that of wildtype PSD-95. These results demonstrate that the full length of PSD-95 is required for it to influence synaptic AMPARs, likely because the C-terminal SH3-GK domain is critical for localizing or stabilizing PSD-95 at the synapse. When overexpressed the truncated forms of PSD-95 containing the first two or three PDZ domains were able to have clear synaptic effects presumably because of their interactions with endogenous, synaptically localized, full length PSD-95. The synaptic stabilization of PSD-95 may be mediated by its C-terminal domain interaction with GKAP and/or SPAR, which link PSD-95 to the postsynaptic protein network (Kim and Sheng, 2004). These results also explain the apparent discrepancy between the previous overexpression study showing that PSD-95PDZ1+2 had a clear effect on increasing synaptic AMPAR EPSCs (Schnell et al., 2002) and that from the PSD-95 mutant mice where the similar protein product was not present in the PSD (Migaud et al., 1998).

We also found that previously studied PSD-95 mutants containing mutations in the N-terminal domain but an intact C-terminal domain, specifically the PSD-95C3,5S and PSD-95ΔPEST mutants, cannot interact with wildtype PSD-95 and as a consequence do not localize to synapses nor increase AMPAR EPSCs. These results suggest that an N-terminal domain mediated interaction, perhaps combined with or mediated by palmitoylation, is required for the enrichment of PSD-95 at synapses and for the effect of PSD-95 on basal AMPAR EPSCs. Previous biochemical studies on whether PSD-95 exists as a monomer or rather as a dimer/multimer due to N-terminal domain interactions are confusing with different conclusions being reached based on the assays and expression systems used (Christopherson et al., 2003; Hsueh et al., 1997; Hsueh and Sheng, 1999; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Topinka and Bredt, 1998). Based on a functional readout of the effects of N-terminal domain mutations (i.e. the effects of PSD-95 on basal AMPAR EPSCs) combined with co-immunoprecipitation assays, our results are consistent with the idea that PSD-95 dimerizes (or multimerizes) via N-terminal domain interactions and that this is critical for its effects on synaptic function. In agreement with previous work (Christopherson et al., 2003), our experiments indicate that the two cysteines at positions 3 and 5 in the N-terminal region are critical for the interaction, as is the PEST motif (residues 10-25). Further biochemical studies will be needed to determine the role of palmitoylation of the two cysteines in mediating dimerization with one possibility being that palmitoylation of the N-terminus exposes a motif that allows dimerization to occur (Christopherson et al., 2003).

The Role of PSD-95 in LTD

Results from overexpression and acute knockdown studies suggest that basal AMPAR-mediated synaptic strength directly correlates with synaptic PSD-95 level under normal conditions. In contrast, the same molecular manipulations of PSD-95 either have no effects on NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses or effects that are dramatically less than those on AMPAR-mediated responses (Ehrlich et al., 2007; Elias et al., 2006; Futai et. al., 2007; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Schluter et al., 2006). In the present work, shRNA-mediated knockdown of PSD-95 had no detectable effect on NMDAR EPSCs (n=145, Fig. 1F). However, in the experiments involving the replacement of endogenous PSD-95 with mutant forms of PSD-95 lacking C-terminal domains (Fig. 1), on average small decreases (15-20%) in NMDAR EPSCs were observed. This raises the formal possibility that changes in NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses may have influenced the ability to trigger LTD when endogenous PSD-95 was replaced with point mutants that impaired or blocked LTD. This possibility, however, can be ruled out by the observation that the effects of replacing endogenous PSD-95 with recombinant PSD-95 on NMDAR EPSCs (Fig. 1F, n=13) were the same as those observed when replacing endogenous PSD-95 with the E17R/Q15A point mutants that blocked LTD (n=16, p > 0.05).

The strong correlation between PSD-95 levels and AMPAR EPSCs raises the possibility that during LTP and LTD, the level of synaptic PSD-95 might change in accordance with the change in synaptic AMPAR content. Ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003) and de-palmitoylation (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002) of PSD-95 have been suggested as two possible biochemical modifications that may regulate synaptic PSD-95 level during synaptic plasticity. Specifically, the removal of PSD-95 from synapses by ubiquitination and de-palmitoylation were reported to be required for agonist-induced endocytosis of AMPARs in cultured neurons (Colledge et al., 2003; El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). Surprisingly, we found that the key mutant used to study the role of PSD-95 poly-ubiquitination in AMPAR endocytosis, PSD-95ΔPEST (Colledge et al., 2003), did not traffic normally to synapses and did not affect basal AMPAR EPSCs. We also examined PSD-95 fused to a GFP with a C-terminal prenylation motif, which prevented the loss of PSD-95 from the membrane due to de-palmitoylation and blocked glutamate-induced AMPAR endocytosis in culture (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). While this construct did enhance basal synaptic responses, it had no effect on LTD. One explanation for these apparent discrepancies in results is that the previous work on agonist-induced AMPAR endocytosis in culture primarily examined the trafficking of non-synaptic AMPARs. Alternatively, the role of PSD-95 in agonist-induced AMPAR endocytosis in cultured neurons may be different than its role in LTD. In either case, our results suggest that membrane dissociation of PSD-95 is not required for LTD, at least during its first 40 or so minutes.

Our results instead suggest a role for PSD-95 in LTD independent of its function in tethering AMPARs at the synapse. Based on the finding that generation of a C-terminal fragment of PSD-95 requiring its SH3-GK domains blocked LTD yet did not prevent PSD-95 from influencing basal synaptic strength, we propose that interactions between the SH3-GK domains and key downstream signaling molecules are critical for the generation of LTD. The effects of the L460P point mutant suggests that a prime candidate for one such key protein is AKAP79/150, an adaptor protein that interacts with PP2B and PKA , two enzymes implicated in LTD ( Kameyama et al., 1998; Mulkey et al., 1994). Via its binding to these enzymes, AKAP79/150 has been suggested to be important for the regulation of AMPAR phosphorylation and hence channel function in dissociated neuron cultures (Colledge et al., 2000; Oliveria et al., 2003; Rosenmund et al., 1994; Tavalin et al., 2002). It also has been reported to translocate from synapses to cytoplasm upon stimulation of NMDARs in neuron cultures in a manner that may contribute to LTD induction and expression (Smith et al., 2006). More consistent with the view of AKAP function in mediating LTD signaling events, rather than in regulating basal AMPAR function, is our finding that the PSD-95 L460P point mutant, which presumably interfered with its binding to AKAP and prevented LTD, still had normal effects on basal AMPAR synaptic responses. Further electrophysiological studies of PSD-95 C-terminal mutants that inhibit specific protein-protein interactions will be required to determine whether PSD-95/AKAP interactions alone or interactions of PSD-95 with other signaling proteins are also required for LTD.

Conclusion

Using a molecular replacement approach, we have examined the role of specific N-terminal and C-terminal molecular motifs in PSD-95 in mediating its role in the regulation of basal synaptic AMPAR function and LTD. We have provided evidence that these two functions of PSD-95 can be clearly dissociated yet that full length PSD-95 is required for both. Our results are consistent with the idea that at the synapse PSD-95 exists as a dimer/multimer due to N-terminal domain interactions. C-terminal domain interactions appear to be important for localizing PSD-95 at the synapse as well as for coupling it to downstream signaling complexes. PSD-95 dimerization or multimerization at synapses is likely required because individual PSD-95 molecules cannot simultaneously interact with the large number of requisite interacting proteins that are required for it to subserve its multiple functions (Figure 10B). Thus, consistent with previous conceptualizations of the role of PSD-95 (Kim and Sheng, 2004; Migaud et al., 1998), based upon our functional analysis of PSD-95 mutants we conclude that PSD-95 serves as both a structural scaffold involved in tethering AMPARs at the synapse and as a signaling scaffold that is required for LTD.

Experimental Procedures

DNA constructs and Virus Production

See Supplementary Materials for details about generation of DNA constructs and lentiviruses.

Dissociated Neuronal Cultures

Dissociated neuronal cultures were prepared from newborn Sprague-Dawley pups as previously described (Schluter et al., 2006). Briefly, papain digested hemispheres of cortex were triturated and plated on poly-D-lysine coated 10 cm culture dishes in B-27 supplemented Neurobasal media and then re-fed subsequently with N-2 supplemented MEM plus GlutaMax (Invitrogen). Glial growth was inhibited by FUDR at 3 DIV.

Antibodies and Western Blots

The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal PSD95 antibody (Affinity Bioreagents), rabbit polyclonal GFP antibody (Molecular Probe), goat anti-mouse conjugated with Alexa680 (Invitrogen), goat anti-rabbit conjugated with Alexa680 (Invitrogen), goat anti-mouse conjugated with IRDye800 (Rockland), goat anti-rabbit conjugated with IRDye800 (Rockland). Neuronal cultures were collected in ice cold RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 50 mM NaPO4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), pH7.4) and diluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (BioRad). Hippocampi were collected and homogenized in ice cold homogenization buffer. A crude synaptosomal fraction P2 was solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer after protein concentrations were adjusted. Samples were separated on 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), transferred on nitrocellulose and decorated with the indicated antibodies. Signals of fluorescent dye labeled secondary antibodies were detected and quantified with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-cor Biotechnology).

HEK293 cells were transfected at 60%–80% confluency in 10 cm plates using Fugene 6 (Roche). Cells were harvested and lysed 24-48 hr after transfection in 500 μl RIPA buffer, extracted at 4°C for 1h and spun for 20 min at >30,000 g. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using 1–3 μg anti-GFP antibody for 1 hr followed by incubation with 30 μl protein A agarose (Roche). The immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times with washing buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, and 0.5% TX-100) followed by a single wash with TBS buffer prior to solubilizing the bound proteins in 30 μl SDS sample buffer. Samples were then run on SDS-PAGE gels for standard Western blotting with indicated antibodies.

Hippocampal Slice Cultures

Procedures for preparation of hippocampal slice cultures were essentially as described (Schluter et al., 2006). Briefly, hippocampi of 7-8 day old rats were isolated, and 220 μm slices were prepared using a Vibratome (Leica Microsystems) in ice-cold sucrose substituted artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; see Electrophysiology section). Slices were transferred onto MilliCell Culture Plate Inserts (MilliPore), and cultured in Neurobasal-A medium supplemented with 1 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid and 20% horse serum. Media was changed every second day.

Electrophysiology

A single slice was removed from the insert, and placed in the recording chamber where it was constantly perfused with ACSF containing (in mM): 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 Glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 4 MgSO4, 4 CaCl2, and continually bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Picrotoxin (50 μM) was included to isolate EPSCs and chloroadenosine (1-2 μM) was added to reduce polysynaptic activity. A single, double-barreled glass pipette filled with ACSF was used as a bipolar stimulation electrode and was placed within 300 μm of the recording pipettes in stratum radiatum. The pipette solution for whole cell voltage-clamp recordings contained (in mM): 117.5 CsMeSO3, 10 HEPES, 10 TEACl, 8 NaCl, 15.5 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.25 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, 5 QX-314. Data were collected using an Axopatch 700A amplifier or two Axopatch 1D amplifiers (Axon Instruments) and digitized at 5 kHz with the A/D converter BNC2090 (National Instruments). Data were acquired and analyzed on-line using custom routines written with Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics). AMPAR EPSCs were recorded at −60 mV and measured using a 2 ms window around the peak. NMDAR EPSCs were recorded at +40 mV and measured 60-65 msec after the initiation of the EPSC. Small, hyperpolarizing voltage steps were given before each afferent stimulus allowing on-line monitoring of input and series resistances. Stimulation pulses were provided at 0.1 or 0.2 Hz. Simultaneous, dual whole-cell recordings were established from an infected and closely adjacent uninfected cell (as indicated by GFP expression and lack thereof). AMPAR EPSCs were collected after adjusting stimulation strength so that AMPAR EPSCs in control cells were 10-50 pA and 40-70 traces were averaged to obtain the basal AMPAR EPSCs from the two cells. Cells were then depolarized to +40 mV, allowed to stabilize and another 25-50 dual component EPSCs were collected to obtain a measurement of NMDAR EPSCs. Comparisons between infected and uninfected cell responses were done using paired t-tests. Statistical analyses among different constructs and conditions were done using one-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) and Tuckey’s HSD t-test. For LTD experiments, at least 6 minutes of stable baseline responses (holding potential of −60mV) were collected before the LTD induction protocol, which consisted of stimulation at 2 Hz for 900 stimulation pulses while holding cells at −45 mV. In Figure 1E and F, the bar graphs showing the effects of sh95 with or without wildtype PSD-95 were previously published in Figure 2H in Schluter et al., 2006 as the experiments examining the effects of PSD-95PDZ1+2 and PSD-95ΔSH3-GK were performed during the same time period.

Slice Culture Imaging

Slices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 4% sucrose in PBS buffer for 3 hours at 4°C, and were mounted with Fluoromount medium (EMS). Images of GFP fluorescence of infected neurons in slices were collected with a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope using a 63X, 1.4NA objective.

Single Spine Imaging

Hippocampal slices cultures were prepared from postnatal day 7 Sprague-Dawley rats. Slices were biolistically transfected with a Helios Gene Gun (Biorad) at 4 days in vitro (DIV 4). Bullets were prepared using 12.5 mg of 1.6 mm gold particles and 80 μg of plasmid DNAs for double transfection (40 μg of each). Slices were maintained on to MilliCell Culture Plate Inserts (Millipore) until imaging at 9 DIV. All experiments were performed at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, in mM): 127 NACl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaHPO4, 2.5 KCl, 1, MgCl2, 25 1 D-Glucose, 2.5 CaCl2) gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Transfected CA1 pyramidal neurons were identified at low magnification (LUMPlanFl 10X 0.30 NA objective, Olympus) based on their red fluorescence and characteristic morphology. Spines of primary or second-order branches of apical dendrites were imaged and photoactivated at high magnification (LUMFL 60X 1.10 NA objective, Olympus) using a custom-made combined 2-photon laser scanning (2PLS) and 2-photon laser photoactivating (2PLP) microscope as previously described (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2005; See Supplementary Materials for additional details.)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Lee, D. Jhung, S. Wu, A. Ghosh, and X. Cai for excellent technical assistance, C. Garner and J. Tsui for helpful discussions, and C. Garner, W.J. Nelson, B.Glick, G. Patterson, and C. Lois for constructs and use of equipment. This work was supported by NIH grants MH063394 (to RCM) and MH075220, MH080310 (to WX), DFG grants SCHL592-1 and SCHL592-4 (to OMS) and grants from the Dana and McKnight Foundations (BS).

References

- Beique JC, Andrade R. PSD-95 regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity in rat cerebral cortex. J. Physiol. 2003;546:859–867. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beique JC, Lin DT, Kang MG, Aizawa H, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. Synapse-specific regulation of AMPA receptor function by PSD-95. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:19535–19540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608492103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Neuronal activity regulates diffusion across the neck of dendritic spines. Science. 2005;310:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1114816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361–379. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RC, Lissin DV, von Zastrow M, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Rapid redistribution of glutamate receptors contributes to long-term depression in hippocampal cultures. Nature. Neurosci. 1999;2:454–460. doi: 10.1038/8123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RC, Beattie EC, Von Zastrow M, Malenka RC. Role of AMPA receptor endocytosis in synaptic plasticity. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:315–324. doi: 10.1038/35072500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS, Sweeney NT, Craven SE, Kang R, El-Husseini Ael D, Bredt DS. Lipid- and protein-mediated multimerization of PSD-95: implications for receptor clustering and assembly of synaptic protein networks. J. Cell. Sci. 2003;116:3213–3219. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Dean RA, Scott GK, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron. 2000;27:107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Snyder EM, Crozier RA, Soderling JA, Jin Y, Langeberg LK, Lu H, Bear MF, Scott JD. Ubiquitination regulates PSD-95 degradation and AMPA receptor surface expression. Neuron. 2003;40:595–607. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:952–962. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven SE, El-Husseini AE, Bredt DS. Synaptic targeting of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 mediated by lipid and protein motifs. Neuron. 1999;22:497–509. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Klein M, Rumpel S, Malinow R. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Malinow R. Postsynaptic density 95 controls AMPA receptor incorporation during long-term potentiation and experience-driven synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:916–927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4733-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini Ael D, Schnell E, Dakoji S, Sweeney N, Zhou Q, Prange O, Gauthier-Campbell C, Aguilera-Moreno A, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Synaptic strength regulated by palmitate cycling on PSD-95. Cell. 2002;108:849–863. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias GM, Funke L, Stein V, Grant SG, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Synapse-specific and developmentally regulated targeting of AMPA receptors by a family of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Neuron. 2006;52:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futai K, Kim MJ, Hashikawa T, Scheiffele P, Sheng M, Hayashi Y. Retrograde modulation of presynaptic release probability through signaling mediated by PSD-95-neuroligin. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:186–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NW, Weimer RM, Bureau I, Svoboda K. Rapid redistribution of synaptic PSD-95 in the neocortex in vivo. PLoS. Biol. 2006;4:e370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Kim E, Sheng M. Disulfide-linked head-to-head multimerization in the mechanism of ion channel clustering by PSD-95. Neuron. 1997;18:803–814. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Sheng M. Requirement of N-terminal cysteines of PSD-95 for PSD-95 multimerization and ternary complex formation, but not for binding to potassium channel Kv1.4. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:532–536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama K, Lee HK, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Involvement of a postsynaptic protein kinase A substrate in the expression of homosynaptic long-term depression. Neuron. 1998;21:1163–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:771–781. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science. 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud M, Charlesworth P, Dempster M, Webster LC, Watabe AM, Makhinson M, He Y, Ramsay MF, Morris RG, Morrison JH, et al. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 1998;396:433–439. doi: 10.1038/24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JM, Zamorano PL, Garner CC. MAGUKs in synapse assembly and function: an emerging view. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2004;61:911–929. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito MA, Sheng M, Tsai LH. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates the N-terminal domain of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 in neurons. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:865–876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4582-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Futai K, Lashuel HA, Lo I, Okamoto K, Walz T, Hayashi Y, Sheng M. Quaternary Structure, Protein Dynamics, and Synaptic Function of SAP97 Controlled by L27 Domain Interactions. Neuron. 2004;44:453–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer M, Kim E, Sheng M. Interaction between the C terminus of NMDA receptor subunits and multiple members of the PSD-95 family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:2157–2163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02157.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Tomita S, Bredt DS. Auxiliary subunits assist AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Science. 2006;311:1253–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.1123339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria SF, Gomez LL, Dell’Acqua ML. Imaging kinase--AKAP79--phosphatase scaffold complexes at the plasma membrane in living cells using FRET microscopy. J. Cell. Biol. 2003;160:101–112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick GN, Bingol B, Weld HA, Schuman EM. Ubiquitin-mediated proteasome activity is required for agonist-induced endocytosis of GluRs. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A photoactivatable GFP for selective photolabeling of proteins and cells. Science. 2002;297:1873–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.1074952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M, Rogers SW. PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Tr. Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Carr DW, Bergeson SE, Nilaver G, Scott JD, Westbrook GL. Anchoring of protein kinase A is required for modulation of AMPA/kainate receptors on hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1994;368:853–856. doi: 10.1038/368853a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans N, Petralia RS, Wang YX, Blahos J, 2nd, Hell JW, Wenthold RJ. A developmental change in NMDA receptor-associated proteins at hippocampal synapses. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1260–1271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01260.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter OM, Xu W, Malenka RC. Alternative N-terminal domains of PSD-95 and SAP97 govern activity-dependent regulation of synaptic AMPA receptor function. Neuron. 2006;51:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell E, Sizemore M, Karimzadegan S, Chen L, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Direct interactions between PSD-95 and stargazin control synaptic AMPA receptor number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:13902–13907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Kim MJ. Postsynaptic signaling and plasticity mechanisms. Science. 2002;298:776–780. doi: 10.1126/science.1075333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Huganir RL. The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2007;23:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Gibson ES, Dell’Acqua ML. cAMP-dependent protein kinase postsynaptic localization regulated by NMDA receptor activation through translocation of an A-kinase anchoring protein scaffold protein. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2391–2402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3092-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein V, House DR, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic density-95 mimics and occludes hippocampal long-term potentiation and enhances long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5503–5506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05503.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin SJ, Colledge M, Hell JW, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Regulation of GluR1 by the A-kinase anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) signaling complex shares properties with long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3044–3051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topinka JR, Bredt DS. N-terminal palmitoylation of PSD-95 regulates association with cell membranes and interaction with K+ channel Kv1.4. Neuron. 1998;20:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.