Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to compare quality of mother-infant interactions during feeding in infants with or without iron deficiency anemia (IDA).

Method

Infants and caregivers were screened at their 9- to 10-month-old health maintenance visits at an inner-city clinic in Detroit. Those who were full-term and healthy received a venipuncture blood sample to assess iron status. Of the 77 infants who met final iron status criteria, 68 infants and mothers were videotaped during feeding interaction at the Child Development Research Laboratory. The quality of mother-infant interaction during feeding was scored on the Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS). Twenty-five infants with IDA (HB < 110 g/L and at least 2 abnormal iron measures) were compared to 43 non-anemic infants (HB ≥ 110 g/L) using ANOVA and GLM models with covariate control.

Results

Mothers of IDA infants responded with significantly less sensitivity to infant cues and less cognitive and social-emotional growth fostering behavior than mothers of non-anemic infants. The pattern of results was similar for scales of contingent behaviors. The magnitude of the differences in maternal ratings was large (0.8-1.0 SD after covariate adjustment). IDA infants were rated significantly lower on clarity of cues and overall (effect sizes 0.5 SD).

Conclusion

IDA in infancy was associated with less optimal mother-infant interactions during feeding. Future interventions might target feeding interaction and consider effects on infant iron status and developmental/behavioral outcomes among IDA infants, as well as infant feeding practices per se.

Keywords: Iron-deficiency anemia, mother-infant interaction, NCAFS, feeding

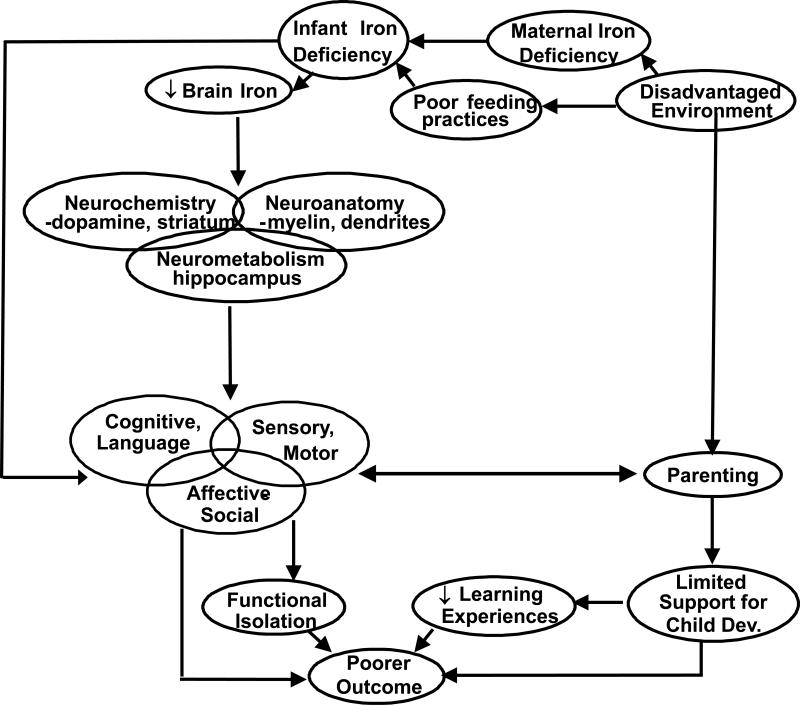

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in infancy is associated with poorer cognitive, motor, and social-emotional development and altered neuromaturation, with poorer short- and long-term outcomes despite iron therapy.1 Animal models and randomized clinical trials of iron supplementation point to a causal relation between lack of iron and altered brain and behavioral development.1 Lozoff and colleagues2 presented an integrative conceptual model of several biological and environmental mechanisms by which early IDA might produce these alterations in infant behavior (see Figure 1). In addition to the effects of iron deficiency on brain and behavior, the model considered environmental disadvantage to be another important factor. Environmental disadvantage may contribute to (a) less facilitative parenting and limited support for child development and (b) poorer feeding practices and greater risk for low nutritional status and IDA.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of effects of early iron deficiency. Modified with permission from Lozoff et al. Child Dev. 1998;69:24-36.

In previous studies focused on IDA and infant development, indirect measures of compromised parenting generally relate to maternal/ family characteristics, such as lower IQ, higher depressive symptoms, and low socioeconomic status. The few available studies of maternal caring behavior suggest less developmentally facilitative behavior in mothers of children with IDA in infancy. For instance, they showed less obvious pleasure in the child, less affection, less eye contact, and they tried less often to get their child to perform tasks on developmental tests.2;3

The present study evaluated mother-infant interaction during feeding. To the best of our knowledge, feeding has not previously been examined in iron deficiency studies. We were especially interested in feeding interaction not only as a social-emotional indicator but also due to its importance for infant food intake, nutritional status, and physical growth.4 We predicted that IDA in infancy would be associated with less optimal maternal and infant interaction and behavior during feeding.

METHODS

Participants

Infants and caregivers were recruited for the study during a routine 9-month visit to the Children's Hospital of Michigan, which serves an economically-stressed, inner-city community in Detroit. The study was approved by the Wayne State University and University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards. Signed informed consent from caregivers was obtained for the screening phase and again for the neurobehavioral study.

Details of the study design have been published previously.5-7 In brief, screening was based on a 10-minute questionnaire and a routine venous blood sample with extra blood (< 5 ml total) for additional iron assays for infants qualified by history. A total of 881 infants were screened between April 2002 and August 2005. Since African-Americans comprised > 90% of the clinic population, recruitment was restricted to those infants. Participation in the neurobehavioral study was further restricted to healthy, full-term singleton infants, born to mothers > 17 years, with birth weight > 5th percentile, without perinatal complications, emergency C-section, maternal diabetes in pregnancy, heavy alcohol use, or other incapacitating condition, who were not in foster care, with no chronic health problem or hospitalization more than once or for > 5 days. Those who also met initial hematologic criteria (see below) and had lead concentration < 10 μg/dl were considered for the neurobehavioral study. The mothers or primary caregivers of 242 potentially qualifying infants were invited to participate; 31% declined, 20% could not be enrolled due to repeated missed appointments, and 2% did not meet entrance criteria on further review. Of 113 infants with neurodevelopmental testing, 77 met final iron status criteria.

Measures and Procedures

Iron status assessment

Initial venous blood tests included a complete blood count, lead, and zinc protoporphyrin/heme ratio (ZPP/H), performed at the Detroit Medical Center. Remaining blood was separated and sent frozen to the laboratory of the late John Beard, Pennsylvania State University, for determination of serum iron, total iron binding capacity, transferrin saturation, ferritin, transferrin receptor (TfR), and markers of inflammation. Details of assay techniques and quality control have previously been reported.8 Using cutoffs from NHANES II,9 NHANES III,10 and CDC publications,11;12 we defined IDA as HB < 110 g/L and at least 2 abnormalities among MCV < 74 fl,12 RDW > 14.0%,11 ZPP/H > 69 μmol/mol heme (corresponding to free erythrocyte protoporphyrin > 80 μg/dl9), transferrin saturation < 12%,9 and ferritin < 12 μg/L.10;11 Non-anemic was defined as HB ≥ 110 g/L. We had also hoped to examine maternal iron status in relation to maternal behavior, but this was not feasible due to missing data for two-thirds of the mothers.

Feeding observation

The neurobehavioral study entailed infant assessments and interviews with primary caregivers at 9-10 months and again at 12-13 months at the Child Development Research Laboratory, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University. The assessment battery typically lasted until early afternoon. For lunch, the research staff provided mothers a meal from a local fast food restaurant, paid for by the research project. We preferred not to offer fast food for the infants, but most mothers asked us to do so, explaining that their baby was familiar with this food. Mothers could also use baby food from home or provided by the project.

At the lunch break, mothers were asked to feed their infants as they normally would. Mother and infant stayed alone in a testing room and were videotaped during feeding. Most mothers ate their own lunch while feeding the baby. All mothers fed their infants solid food. The feeding interaction observation concluded either when the mother said the infant had finished eating, no more food was available, or 20-30 minutes had elapsed, at which time one of the research staff (voice piped into the room) asked the mother if they were done. After lunch, when most infants napped, mothers were interviewed about infant health and family background.

Feeding was not recorded for 2 of the 77 infants and could not be coded for 7 others due to technical problems, such as no sound or siblings in the room. Thus, the final sample for analysis consisted of 68 infants (25 IDA and 43 non-anemic) and their mothers. Of these 68 dyads, 2 used baby food exclusively, 5 offered both baby food and fast food, and the rest offered fast food exclusively for the infant's meal.

Assessment of mother-infant interaction during feeding

The quality of the mother-infant interaction during the videotaped feeding session was scored using the Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale (NCAFS) 13. The NCAFS is an observational measure with established normative data. It has good evidence of total and subscale internal consistency and test-retest reliability as well as construct, concurrent and predictive validity.13 The assessment was conducted by a psychologist (RA-S) who was certified in NCAFS administration and scoring (i.e., met criterion of at least 85% reliability for each scale on a series of standardized case studies). Prior to coding study videotapes, RA-S established inter-rater reliability with co-author MK-E (also NCAFS certified) of 90%, which is similar to the percentage of agreement reported by others.14

The NCAFS contains 76 binary items that are scored as presence or absence of behavior. Scoring of each item is simply “YES” or “NO”. The 76 items are organized into six conceptually-derived subscales. The four caregiver subscales include sensitivity to infant cues (16 items), response to infant distress (11 items), social-emotional growth fostering (14 items), and cognitive growth fostering (9 items). The two infant subscales are clarity of cues (15 items) and responsiveness to caregiver (11 items). Subscales scores reflect the sum of items scored “YES”. Each subscale score can range from zero, indicating that none of the item behaviors was observed, to the total number of items in the subscale, indicating that all item behaviors were observed in the interaction. Higher scores indicate more positive behavioral capacities. The total caregiver score (sum of four subscale scores) can range from 0 to 50, and the total infant score (sum of two subscale scores) can range from 0 to 26. The sum of the two scores yields a dyadic score with a maximum of 76. Sumner and Spietz (1994)13 reported moderate internal consistency (α = 0.56 - 0.69) for parent- and infant-specific subscales (higher coefficients for parent scores) and good internal consistency for the total scores (total parent score α = 0.83, total infant score α = 0.73, and combined parent-infant score α = 0.86). We also found that internal consistency was moderate for specific subscales (range = 0.52 - 0.79) and good for the total scores (0.84, 0.71, and 0.88, respectively).

In addition, 18 of the 76 items relate to parent and infant contingent interaction. Caregiver contingent behavior items are organized into four subscales: sensitivity to cues (6 of the 16 items), response to infant distress (6 of the 11 items), social-emotional growth fostering (1 of the 14 items), and cognitive growth fostering (2 of the 9 items). An infant contingent score is derived from the responsiveness to caregiver subscale (3 of the 11 items). Scores for each contingency subscale can range from zero to the total number of items in the subscale. The four caregiver subscale scores combine to create a total parent contingency score with a possible maximum score of 15. The sum of the parent and infant contingency scores yields a dyadic contingency score with a maximum of 18. Sumner and Spietz (1994)13 reported good internal consistency reliability for the parent contingency score (α = 0.73) but very low for the infant contingency score (α = 0.19). Similar Cronbach's alphas were found in this study (0.74 and 0.20, respectively).

Sensitivity to cues includes such items as “caregiver only offered food when child is attending” or “caregiver varies the intensity of verbal stimulation during feeding”. The response to infant's distress subscale indicates the caregiver's recognition and appropriate action to alleviate child's distress. The social-emotional growth fostering subscale identifies parental behaviors that convey positive emotional signals and reinforcement of child behaviors, and the cognitive growth fostering subscale notes behaviors providing stimulation appropriate to the infant's level of understanding. Of the two child subscales, clarity of cues rates whether an infant's cues are “easy” or “difficult” for a caregiver to understand, such as “child signals readiness to eat”. The responsiveness to caregiver subscale rates child behaviors in response to caregiver cues, for example, “child responds to games, social play or social cues of caregiver during feeding”. The contingency subscales focus on responsiveness of parent and/or infant to specific behaviors of one another, e.g., “caregiver smiles, verbalizes or touches child within five seconds of child smiling or vocalizing at caregiver”.13

Although the study design called for infants to be reassessed after 3 months of iron therapy (at 12-13 months), our analysis focuses on feeding behavior at 9-10 months for two reasons. The ceiling of the NCAFS is 12 months, and it is not clear how well the scales apply when infants start feeding themselves, as is developmentally appropriate at 12-13 months. In addition, there was considerable uncertainty about whether infants received iron. We could not use hematologic response to iron to confirm iron intake, because 46% of infants did not come for a repeat blood test at 12 months.

Background Characteristics

Infant Measures

Infant birth outcomes were taken from the hospital records. Infant growth, including weight and height, were measured during the visit to the Child Development Research Laboratory, and weight-for height, weight-for-age, and height-for-age z-scores were determined. Infant health and breast feeding information were obtained from a maternal questionnaire during the visit at the Child Development Research Laboratory.

Maternal Demographic and Health Data

Maternal demographic and health data, including maternal age, marital status, education, occupation, alcohol and drug use, prenatal care, and health were obtained from either the screening questionnaire or maternal interview. A socioeconomic status index was computed on the Hollingshead scale15, separately for the primary caregiver and partner based on their educational attainment and occupational status, which was averaged together if both were employed; if not, SES was based on the educational attainment and occupational status of the head of household. The continuous Hollingshead SES measure ranges from 8 to 66.

Maternal Questionnaires

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)16

The BDI is a 21-item, self-report instrument completed by the mother to assess depressive symptoms in the previous week. Items are rated on a four-point scale and summed to a total score (score range 0-63). Extensive data support its internal consistency and content validity.16,17 Internal consistency for our sample was α = xxx.

State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI)18

The STAI is a 40-items self-reported scale for assessing state (20 items) and trait (20 items) anxiety. Items are rated on a four-point scale (1=not at all, and 4=very much so), and summed into two total scores (score range 20-80). Detailed information regarding reliability and validity for STAI is reported in the Test Manual.18 Internal consistency for our sample was α = xxx.

Social Support19

The quality of social support was assessed in an interview adapted from Crnic et al. (1983). Mothers respond to a series of questions in which they rated the availability and satisfaction of various sources of support (e.g. intimate, friendship and community). The satisfaction questions (20 items) were rated on a four-point scale (1=not at all, and 4=very much so) to provide a total satisfaction score. Internal consistency was found to be adequate for the factor in this sample (α = ).19

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment-Revised20

The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory is a semi-structured interview designed to assess the quality and quantity of stimulation and support available to a child in the home environment. At the 12-month assessment, the Infant/Toddler HOME was administered using a script developed by one of the authors (SJ) for administration of the HOME in the laboratory. The Infant/Toddler HOME is composed of 45 items clustered into six subscales: 1) Emotional and Verbal Responsivity, 2) Avoidance of Restriction and Punishment, 3) Organization of the Environment, 4) Provision of Appropriate Play Material, 5) Maternal Involvement with the Child, and 6) Opportunities for Variety in Daily stimulation. All items are rated as being present (scored “YES”) or absent (scored “NO”). A total score reflects the sum of items scored “YES” (range 0 - 45). The HOME validity for use with black samples has been established.21 Mean inter-observer reliability in the Child Development Research Laboratory (Wayne State University) was 95% (range = 88-100%). Internal consistency for our sample was α = xxx.

Life Events Scale (LES)22

The LES is a 43-item questionnaire which was administered to measure negative life events experienced in the last year. If an event occurred, the mother rated how stressful she found each event on a seven-point Likert scale (0= not at all, and 6=highly stressful), which yields a summary score. This measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity and is related to measures of stress and depression.22 The Cronbach's alpha for the present sample was xx.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis used SAS version 9.1.3.23 Infant iron groups (IDA vs. non-anemic) were compared on background characteristics and iron status. All comparisons were made using t tests for continuous variables and Chi-square analyses for categorical variables. Separate univariate analyses were used for each of the six NCAFS subscales, two total scales, and contingency scales. General linear model (GLM) analysis was used to assess the effects of infant iron group controlling for covariates.

To evaluate potential covariates, Pearson correlations were used to assess the relation of NCAFS subscales and total scores to background characteristics variables. Potentially confounding variables were considered in the initial models if they were even weakly related to NCAFS outcomes (p ≤ .10). Covariates that remained at p ≤ .10 in the final models were retained. Unadjusted means and standard deviations are presented in the text; adjusted means and standard errors are shown in the figures.

RESULTS

Background Characteristics and Iron Status

Background characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant group differences in background characteristics, except that the IDA group had somewhat poorer growth. The proportion breast feeding and the duration of breast feeding were similar. Only four infants (2 IDA and 2 non-anemic) were still breast feeding at the time of the initial evaluation (9-10 months). All infants routinely ate solid foods and juices. Almost all took formula; breast milk was the sole source of milk for only 1 infant. Iron status differed across groups by definition (Table 2).

Table 1.

Background characteristics by iron status group*

| Iron-deficient anemic (IDA) | Non-anemic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N † | 25 | 43 | |

| Infant | |||

| Gender, % male (n) | 48.0 (12) | 55.8 (24) | 0.53 |

| Birth weight, kg | 3.27 ± 0.31 | 3.27 ± 0.36 | 0.98 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 39.6 ± 0.76 | 39.9 ± 1.2 | 0.26 |

| Age at 9-month visit, months | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 0.14 |

| Weight-for-height z-score | 0.2 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Weight-for-age z –score | -0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 1.3 | 0.02 |

| Height-for-age z –score | -0.5 ± 0.9 | -0.4 ± 1.2 | 0.81 |

| Breast-fed, % yes (n) | 36.0 (9) | 46.5 (20) | 0.40 |

| Duration if breast-fed, weeks | 21.7 ± 14.9 | 18.5 ± 14.2 | 0.58 |

| Mother and family | |||

| Mother married, % (n) | 4.0 (1) | 11.6 (5) | 0.40 |

| Maternal age, years | 24.6 ± 5.7 | 24.5 ± 5.8 | 0.97 |

| Socioeconomic status | 27.4 ± 9 | 28.6 ± 7.8 | 0.58 |

| BDI | 6.1 ± 5.1 | 6.3 ± 4.9 | 0.84 |

| Maternal anxiety (Trait) | 32.9 ± 9.5 | 36.3 ± 9.4 | 0.20 |

| Maternal anxiety (State) | 30.3 ± 10.2 | 32.2 ± 9.1 | 0.48 |

| Social support | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.07 |

| HOME score | 32.7 ± 5.4 | 31.4 ± 6.2 | 0.43 |

| Life events scale | 6.2 ± 4.5 | 5.4 ± 4.2 | 0.55 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD or % (n) for categorical variables. P-values are based on t tests for continuous variables and Chi-square analyses for categorical variables.

N varies slightly due to occasional missing data for some measures.

Table 2.

Iron status of study groups*

| Iron-deficient anemic (IDA) | Non-anemic | Cutoff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N † | 25 | 43 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L‡ | 102.2 ± 5.2 | 120.6 ± 5.4 | < 110 g/L |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fl‡ | 71.8 ± 4.7 | 75.6 ± 4.4 | < 74 fl |

| Zinc protoporphyrin/heme ratio, μmol/mol heme‡ | 115.3 ± 37.1 | 85.0 ± 45.7 | > 69 μmol/mol heme |

| Red cell distribution width, %‡ | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 13.7 ± 1.1 | > 14.0% |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 30.3 ± 24.5 | 30.8 ± 25.4 | < 12 μg/L |

| Transferrin saturation, %§ | 8.2 ± 5.8 | 5.5 ± 2.7 | < 12% |

| Lead, μg/dl | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 2.1 | ≥ 10 μg/dl |

Values are means ± SD and the cutoffs used to indicate abnormality.

N varies slightly due to occasional missing data for some measures.

IDA significantly different from non-anemic at p ≤ .01.

IDA different from non-anemic at p = .10.

Feeding Interaction Outcomes

Parent subscales and total scores

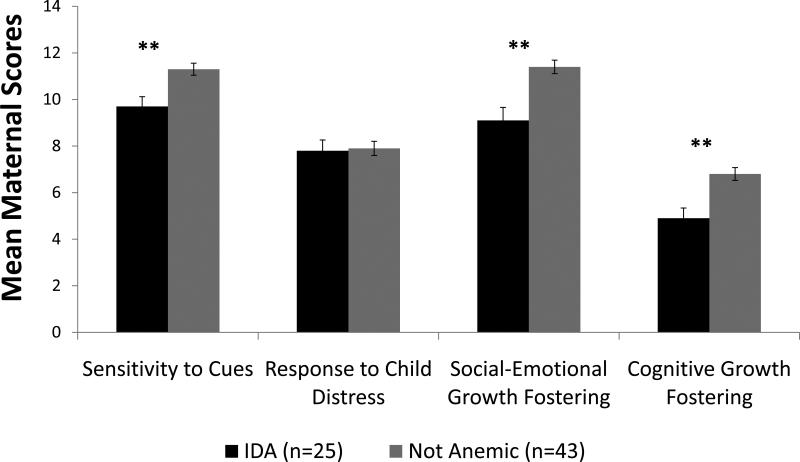

There was a significant iron group effect for maternal sensitivity to infant cues. Mothers of IDA infants responded with less sensitivity to infant cues compared to mothers of non-anemic infants (mean [SD]) = 9.7 [2.2] IDA vs. 11.3 [1.9] non-anemic; p <.01). Maternal social-emotional growth fostering and cognitive growth fostering also showed significant iron group effects. In the IDA group, mothers responded with less social-emotional growth fostering (mean [SD]) = 9.4 [2.8] IDA vs. 11.7 [1.9] non-anemic; p <.01) and less cognitive growth fostering (mean [SD]) = 5.4 [2.2] IDA vs. 6.8 [1.8] non-anemic; p <.01). Maternal response to the infant's distress did not differ by iron group (mean [SD]) = 7.8 [2.3] IDA vs. 7.9 [2.0] non-anemic). GLM analyses showed similar results. Adjusted means, standard errors, and p-values of each parent subscale by infant iron group are presented in Figure 2. Maternal anxiety was a significant covariate for social-emotional growth fostering and cognitive growth fostering. The total parent score was significantly lower in the IDA group than the non-anemic group (mean [SD]) = 32.3 [6.7] IDA vs. 37.7 [5.3] non-anemic; p <.01). Controlling for infant age, GLM revealed similar results (Cohen's d = 0.8; p <.01).

Figure 2.

Maternal NCAFS scores by infant iron status. Values shown are adjusted means ± SE. Maternal anxiety was a significant covariate for social-emotional growth fostering and cognitive growth fostering. ** p ≤.01

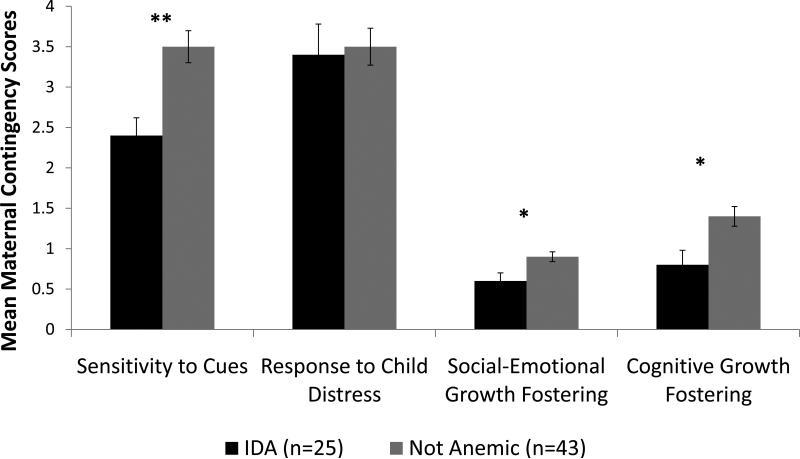

Parent contingency subscales showed a similar pattern. The IDA group received lower maternal contingency scores compared to the non-anemic group in maternal sensitivity to infant cues (mean [SD]) = 2.4 [1.1] IDA vs. 3.5 [1.3] non-anemic; p <.01), maternal social-emotional growth fostering (mean [SD]) = 0.6 [0.5] IDA vs. 0.9 [0.4] non-anemic; p <.01), and maternal cognitive growth fostering (mean [SD]) = 0.8 [0.9] IDA vs. 1.4 [0.8] non-anemic; p <.01). GLM analyses showed similar results (p <.05). Adjusted means, standard errors, and p-values of each parent contingency subscale by infant iron group are presented in Figure 3. Significant covariates were gestational age for maternal sensitivity to infant cues and maternal anxiety for cognitive growth fostering. The total parent contingency score was lower in the IDA group than the non-anemic group (mean [SD]) = 7.4 [3.1] IDA vs. 9.2 [2.8] non-anemic; p <.05). GLM analysis revealed similar results (Cohen's d = 0.6; p =.01).

Figure 3.

Maternal NCAFS contingency scores by infant iron status. Values shown are adjusted means ± SE. Significant covariates were gestational age for sensitivity to cues and maternal anxiety for cognitive growth fostering. * p ≤ .05 ** p ≤ .01

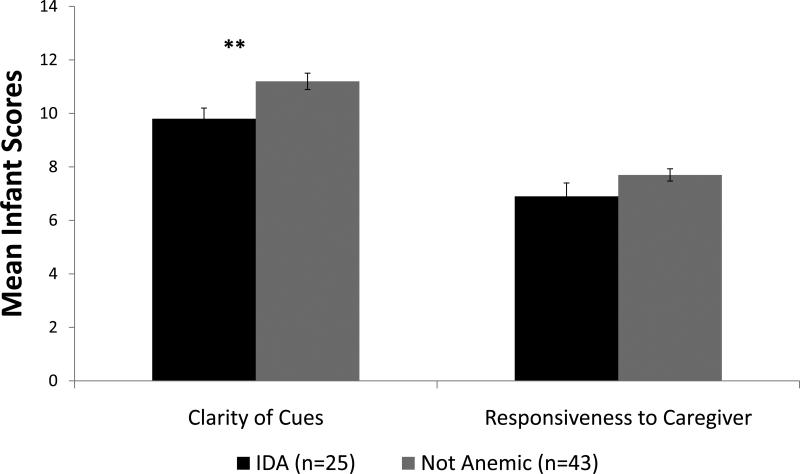

Infant subscales and total scores

IDA infants exhibited less clarity of cues (mean [SD]) = 9.8 [2.0] IDA vs. 11.2 [2.0] non-anemic; p <.01). Controlling for Infant age and gestational age, GLM analyses showed similar results (p =.04). No group differences were found in infant responsiveness to caregiver (mean [SD]) = 6.9 [2.5] IDA vs. 7.7 [1.5] non-anemic; p =.10). Adjusted means, standard errors, and p-values of each infant subscale by infant iron group are presented in Figure 4. The infant total score was lower in the IDA group than the non-anemic group (mean [SD]) = 16.7 [4.1] IDA vs. 18.9 [3.0] non-anemic; p =.01). Infant birth weight, gestational age, age, and socio-economic status were significant covariates for the infant total score. In the GLM analyses, results were similar after covariate control (Cohen's d = 0.5; p <.05). There was no difference between IDA and non-anemic groups in the infant contingency scale.

Figure 4.

Infant NCAFS scores by infant iron status. Values shown are adjusted means ± SE. Infant age and gestational age were significant covariates for clarity of cues. ** p ≤ .01

DISCUSSION

Our results extend previous studies of mother-infant interaction in IDA samples to feeding. As predicted, IDA in infancy was associated with less optimal mother-infant interaction during feeding. Compared to mothers of non-anemic infants, mothers of IDA infants responded with less sensitivity to their infant's cues and less cognitive and social-emotional growth fostering, and IDA infants exhibited less clarity of cues. Our findings support earlier studies that demonstrate less developmentally supportive maternal caring behavior and social-emotional behaviors for IDA infants.2;3

The observed maternal interactive behavior during feeding in the IDA group supports the conceptual model suggested by Lozoff et al. (Figure 1).2 Lower maternal sensitivity to infant cues during feeding might contribute to poorer feeding practices and infant IDA. Poorer feeding practices might also contribute to poorer growth of IDA infants in our study. In addition, lower scores in maternal cognitive and social-emotional growth fostering may be an indicator of less optimal parenting, a fundamental factor in the conceptual model of IDA effects. These differences were observed despite a lack of group differences in maternal sociodemographics and socioemotional function in this sample.

Social-emotional differences are commonly reported in studies of IDA in infancy (reviewed in24-26). We previously reported that IDA infants in the same sample were shyer, less socially engaged, less soothable, and less positive in affect during structured assessments,6 but differences in infant behavior seemed less prominent in the familiar feeding context. This observation supports the suggestion in previous studies that alterations in infant behavior are more pronounced when the IDA infant experiences unfamiliar settings and people or other somewhat stressful circumstances.2;3;6;27;28 Since social-emotional alterations in IDA infants may contribute to lower maternal sensitivity and perhaps to poorer feeding practices, the direction of effects is unknown in our study.

The study is limited by small sample size, inability to assess response to iron therapy, and lack of information on maternal iron status. As in any small study, it is crucial to replicate the findings in larger samples. Our inability to examine maternal iron status in relation to maternal behavior is disappointing, since evidence is accumulating that this is an important factor. For instance, in a prospective, randomized intervention study of maternal iron status and mother-infant interaction, IDA mothers were more negative, less responsive, and exhibited more “negative mothering” characteristics than non-anemic or iron-treated IDA mothers.29 Thus, it seems that maternal nutritional status during pregnancy and the early postpartum period has the potential to influence maternal and infant behavior. Regarding other limitations of our study, it is unclear whether the results will generalize to other populations. Future studies that examine mother-infant feeding interaction in different populations are needed in IDA research. Further research is also needed to understand the effects of iron therapy on mother-infant interaction during feeding and the relations between maternal iron status and maternal behavior.

Previous studies have shown the importance of caring behavior during feeding for infant food intake. Caregiver affection and responsiveness, warmth and verbal interaction improve infant's readiness to eat and nutrient intake of young children.30 We speculate that early interventions that help mothers to better understand their infants’ cues or lack thereof can foster more facilitative caring behavior and might improve feeding practices, infant iron status, and developmental/behavioral outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the study families; our colleagues, Mary Lu Angelilli, Rosa Angulo-Barroso, Charles Nelson, and Joseph L. Jacobson for their contributions to study design; the late John Beard for his contributions to the assessment of iron status; Matthew Burden, Douglas Fuller, Margo Laskowski, Tal Shafir, Renee Sun, Brenda Tuttle, and Jigna Zatakia, for their contributions to recruitment, infant assessment, maternal interviewing, and data management; Min Tao and Kelly Zidar for assistance with statistical analyses; Katy M. Clark for help with manuscript preparation; Winnie Ho for assistance with figures; and William Neeley (Director, Detroit Medical Center University Laboratories) and the laboratory staff at Detroit Medical Center and Pennsylvania State University for performing the hematologic and biochemical assays. All investigators in the Brain and Behavior in Early Iron Deficiency Program Project contributed to our thinking about mother-infant interaction during feeding.

Supported by a program project grant from NIH (P01 HD39386, Betsy Lozoff, Principal Investigator) and a grant from the Joseph Young, Sr., Fund from the State of Michigan to Sandra W. Jacobson. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozoff B, Klein NK, Nelson EC, et al. Behavior of infants with iron deficiency anemia. Child Dev. 1998;69:24–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corapci F, Radan AE, Lozoff B. Iron deficiency in infancy and mother-child interaction at 5 years. J Behav Dev Pediatr. 2006;27:371–378. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200610000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson M, Landman M. ‘It's not just about food’: mother-infant interaction and the wider context of nutrition. Matern & Child Nutr. 2007;3:292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burden MJ, Westerlund AJ, Armony-Sivan R, et al. An event-related potential study of attention and recognition memory in infants with iron-deficiency anemia. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e336–e345. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lozoff B, Clark KM, Jing Y, et al. Dose-response relationships between iron deficiency with or without anemia and infant social-emotional behavior. J Pediatr. 2008;152:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafir T, Angulo-Barroso R, Jing Y, et al. Iron deficiency and infant motor development. Early Hum Dev. 2007;84:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozoff B, Angelilli ML, Zatakia J, et al. Iron status of inner-city African-American infants. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:112–121. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Life Sciences Research Office . Assessment of the Iron Nutrition Status of the U.S. Population Based on Data Collected in the Second National Health and Nutrition Survey, 1976-1980. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology; Bethesda, MD: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Looker AC, Dallman P, Carroll MD, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. JAMA. 1997;277:973–976. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540360041028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. MMWR. 1998;47:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control . Healthy People - 2000 National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives Final Review. Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumner G, Spietz A. NCAST caregiver/parent-child interaction feeding manual. University of Washington School of Nursing; Seattle, WA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodges EA, Houck GM, Kindermann T. Reliability of the Nursing Child Assessment Feeding Scale during toddlerhood. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2007;30:109–130. doi: 10.1080/01460860701525204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression inventory II. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, et al. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychopatol. 1998;31:160–168. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crnic KA, Greenberg MT, Ragozin AS, et al. Effects of stress and social support on mothers and premature and full-term infants. Child Dev. 1983;54:209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Revised Edition University of Arkansas Press; Little Rock, AR: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley RH, Caldwell BM. The HOME Inventory: A validation of the preschool scale for black children. Child Dev. 1981;52:708–710. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS 9.1.3. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C. A review of studies on the effect of iron deficiency on cognitive development in children. J Nutr. 2001;131:649S–668S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.649S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, et al. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:S34–S43. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozoff B. Iron deficiency and child development. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28:S560–S571. doi: 10.1177/15648265070284S409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozoff B, Wolf AW, Urrutia JJ, et al. Abnormal behavior and low developmental test scores in iron-deficient anemic infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1985;6:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozoff B, Felt BT, Nelson EC, et al. Serum prolactin levels and behavior in infants. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:4–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00148-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez EM, Hendricks MK, Beard JL, et al. Mother-infant interaction and infant development are altered by maternal iron deficiency anemia. J Nutr. 2005;135:850–855. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engle PL, Bentley M, Pelto G. The role of care in nutrition programmes: current research and a research agenda. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:25–35. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]