Abstract

Herein, I describe my experience (spanning 40 years) in helping to develop the specialty of cardiovascular surgery in Syria. Especially in the early years, the challenges were daunting. We initially performed thoracic, vascular, and closed-heart operations while dealing with inadequate facilities, bureaucratic delays, and poorly qualified personnel. After our independent surgical center was established in early 1976, we performed 1 open-heart and 1 closed-heart procedure per day. Open-heart procedures evolved from the few and simple to the multiple and complex, and we solved difficulties as they arose. Today, our cardiac surgical center occupies an entire 6-floor building. We have 12 cardiac surgeons, 10 surgical residents, a formal 6-year surgical residency program, a pediatric cardiac unit, an annual caseload of 1,600, and plans to double our productivity in 2 years.

The tribulations of establishing sophisticated surgical programs in a developing country are offset by the variety of clinicopathologic conditions that are encountered, and even more so by the psychological rewards of overcoming adversity and serving a population in need. This account may prove to be insightful for Western-trained physicians who seek to develop specialized medical care in emerging societies.

Key words: Cardiac surgical procedures/economics/education/trends; health planning; health resources/organization & administration; health services needs & demand; heart diseases/epidemiology/surgery; history/20th century/21st century; international cooperation; policy making; surgery department, hospital/classification/organization & administration; Syria/epidemiology

When I look back on my 40 years as a cardiothoracic surgeon in Syria, I am overwhelmed with feelings of gratitude for the chance to help develop cardiac surgery in my native country and for my American mentors who made this possible. Although my account is not unique and probably resembles that of many physicians from developing countries who acquired specialty training abroad and returned to apply what they had learned, I want to relate my experience, with the objective of offering guidelines and insights from which young surgeons in similar situations might benefit.

Background

I come from a middle-class Syrian family, and my late father, a well-known general practitioner, advised that I enter the American University of Beirut for my undergraduate medical training. I have reaped the benefits of that decision to this day. I was introduced to the practical, evidence-based methods of American medical education, which I believe are the best in the world.

My surgical training in the United States (1962–1969) was mainly at Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital under Dr. Fiorindo A. Simeone and also at St. Louis University Hospital under Dr. C. Rollins Hanlon. My thoracic surgical training was at Henry Ford Hospital, in Detroit, under Drs. Conrad R. Lam and Rodman E. Taber. I don't have happy memories of those years, because I had to work very hard to compete with my American colleagues and fulfill the requirements for my Board examinations. However, in retrospect, I have only the greatest respect and admiration for my department chiefs and for the American style of residency training, which, rigorous though it was, gave the resident full responsibility in patient care and did not distinguish between U.S. and foreign medical graduates.

When I returned to Syria in 1969, I joined the Damascus University medical faculty. Aside from a few closed mitral commissurotomy procedures, heart surgery was not practiced in my native country. I resolved to establish the first cardiac surgical department in Syria.

The Difficulties

Syria in 1970 was a small Middle Eastern country of 6.3 million people. Its relative lack of wealth and resources, per capita income of about U.S. $800, and illiteracy rate of over 50% had a detrimental effect on health standards. Life expectancy was only 55 years, the infant mortality rate was 1%, and infectious and parasitic diseases were the leading causes of death. Although approximately 1,000 doctors graduated each year from Syrian medical schools, they continually emigrated, which kept the physician-to-population ratio at about 1:3,000. These figures no longer apply to Syria, but they are typical of emerging societies, which comprise about two thirds of the world's population.

The main university hospital, Mouassat Hospital, was a 1,200-bed facility that accepted indigent patients from all over the country. As soon as I began working there, it was apparent that huge obstacles lay ahead in establishing a functional cardiothoracic surgical unit at Damascus University.

The difficulties started with the patients themselves. As a direct consequence of poor health education, patients and their relatives either found it difficult or considered it unnecessary to abide by hospital regulations and physicians' instructions in regard to visiting hours, blood donation, operative and autopsy permits, and follow-up appointments. Moreover, patients did not fully understand or appreciate operative risk.

The second set of challenges involved the hospital's inadequate facilities, its deficient services, and the huge demands placed upon it. The occupancy rate was always 100%, and the wait for admission was several months. The medical equipment was outdated and desperately needed maintenance. Buying new equipment was impeded by inefficient bureaucratic systems and scarce resources.

A related set of problems involved the employees. For several reasons (chiefly financial), the hospital was understaffed, and most of the nurses, technicians, attendants, and aides were unenthusiastic because of their meager salaries. Furthermore, most of them were insufficiently trained in modern patient care. The operating rooms lacked professional personnel, had deficient equipment, and were used effectively for no longer than 4 or 5 hours per day. Aseptic technique was not strictly adhered to.

Faced with the inherent educational deficiencies in a hospital that had all of the aforementioned problems and no internationally recognized residency program, the resident staff lacked incentive. Early in their postgraduate training, residents concentrated on finding ways to leave for Europe or the U.S. Most of those who left never came back, thus perpetuating the poor health standards in the country.

In addition to all these issues, the surgeons had a few difficulties of their own, including low stipends, no hospital library, and shoddy medical records that did not enable even modest clinical research.

The Advantages

The gloomy picture that I have just painted of what the Western-trained specialist from a developing country might expect upon returning home does have a bright side, strange as this may seem.

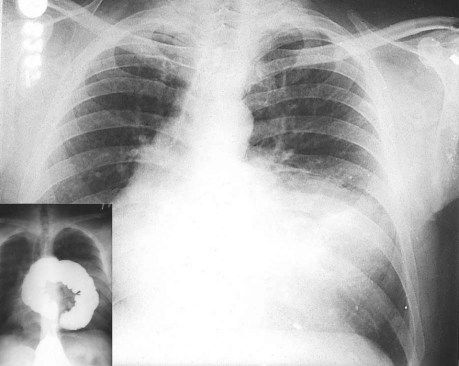

To begin, the amount and variety of clinicopathologic material that the specialist encounters can be very educational. Patients in emerging societies tend to tolerate their ailments for relatively long periods before consulting a physician, with the result that a wide spectrum of disease conditions, rarely reported in the Western medical literature, can be observed. I encountered such clinical entities when I started my Syrian practice as a thoracic and vascular surgeon, and thereafter when cardiac surgery was initiated (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).1

Fig. 1 A 63-year-old man with a giant chest-wall tumor originating from the sternum. The tumor, which had been growing for more than a decade, proved to be a slow-growing fibrosarcoma. The inset shows the lesion after removal.

Fig. 2 For several years, a 40-year-old patient had had gastrointestinal symptoms that were not definitively diagnosed until a chest radiograph and barium enema (inset) revealed a giant Morgagni hernia, which was repaired through an abdominal approach.

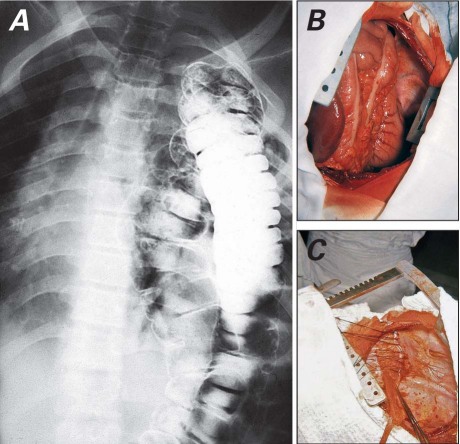

Fig. 3 A) A Bochdalek hernia in an adult who had never had a chest radiograph before this diagnosis. Photographs show B) the view upon opening the left chest and C) the repair.

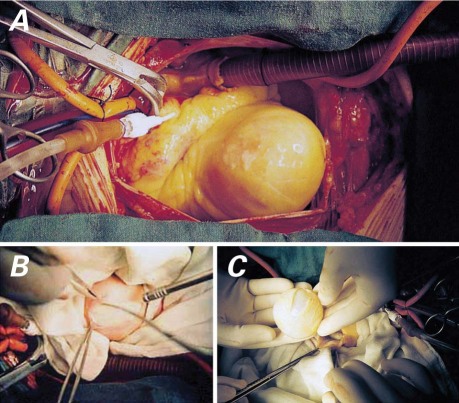

Endemic diseases, especially infectious and parasitic, present themselves in abundance. Hydatid disease of the lungs was the first indication for thoracotomy when I started my practice in Mouassat Hospital 40 years ago. When we initiated open-heart surgery later, we encountered cardiac echinococcosis, of which we have observed 21 cases so far and reported on 19 (Fig. 4).2 Another endemic disease was chronic constrictive pericarditis. Cardiac decortication was a common operation in the early years of our practice.3

Fig. 4 Intraoperative photographs show A) a solitary hydatid cyst in the left ventricle, B) enucleation of the cyst, and C) the complete cyst after excision.

Perhaps the most salient endemic heart condition was rheumatic heart disease, which was the main indication for open-heart procedures in our early cardiac surgical experience. In the Middle East, rheumatic heart disease starts early in life and takes a virulent course.4 One challenge that we faced was treating patients with severe pulmonary hypertension secondary to mitral stenosis, in whom pulmonary artery pressures equaled or exceeded systemic values. Approximately one eighth of these patients developed paradoxically elevated pulmonary artery pressures immediately after mitral commissurotomy or valve replacement. We found that we could save the patients by instilling vasodilation agents directly into the pulmonary artery.5

Finally, because the returning cardiothoracic surgeon usually works in a large referral center, he is likely to encounter rare and reportable disease entities (Fig. 5).6–9

Fig. 5 Photograph shows a neonate with ectopia cordis.

An even more important advantage of working in a developing region is of a psychological nature. I felt a strong sense of accomplishment in the face of unfavorable odds, fulfillment from meeting a dire need in a deprived community, and gratification in training many young and aspiring surgeons.

The Early Years

Our first few years were the most difficult. Our team had to bear the consequences of all of the local problems described above while trying to introduce new and more complex operations.

In the beginning, I had to limit my practice to thoracic and vascular surgery, and I learned from managing clinical situations—pulmonary echinococcosis, for example—that I had not encountered during my training in the U.S. I was also responsible for most of the emergency vascular cases, which gave me great expertise in that area.

In 1970, I trained a nurse to scrub and assist in the operating room for the first time in Syria, and I managed to equip one of the 6 hospital operating rooms for thoracic and vascular surgical procedures. A small intensive care unit (ICU) was also established in a rarely used office area of the hospital.

Eventually, I began performing closed-heart operations, starting with the division of a patent ductus arteriosus, followed by a Blalock-Taussig shunt. Because we had no adequate echocardiographic or cardiac catheterization facilities, we freely used palliative systemic–pulmonary shunts and pulmonary artery banding in infants, sometimes purely on the basis of chest radiographs. Despite my limited experience with closed mitral commissurotomy in the U.S., I regularly had to perform this operation in Syria because of the large number of patients with mitral stenosis and severe pulmonary hypertension.

Damascus University allocated a small grant from the Kuwaiti government to purchase the minimum equipment necessary to start performing open-heart surgery. In Syria, stray dogs were officially targeted for elimination because of their role as carriers of hydatid disease. We spent a short period operating on these animals in the hospital basement before attempting surgery in human beings. On 21 August 1971, we performed our first open-heart procedure in a young woman who had an atrial septal defect. This was followed by 5 other simple cases. Although all 6 patients lived and did well, it was apparent that we were headed in the wrong direction:

Preparing for and performing each procedure took such a toll on the operating room staff that it disrupted the usual flow of patients and caused our surgical colleagues to express strong reservations.

During one of the operations, the electrical power failed (a fairly common occurrence in those days), and we almost lost the patient.

One patient developed a severe sternal wound infection.

Our funds from the Kuwaiti grant were soon depleted.

I was convinced that if we were to develop a serviceable cardiac surgical program for indigent patients in Syria, it was mandatory to have an independent unit, separate from the main hospital. It had to be adequately funded by the government, and its key personnel had to be trained in recognized centers abroad. Our open-heart program was therefore temporarily suspended. Soon afterwards, I received a Presidential Award for establishing open-heart surgery in Syria, and I used that occasion to explain my views to the country's top leadership. My proposals were accepted.

While the bylaws of the independent surgical unit were being formulated, I sent 6 nurses for training in the operating rooms and ICU at the American University of Beirut, sent an anesthesiologist and a perfusionist for 6-month training courses at the Texas Heart Institute (THI) in Houston, and sent 2 College of Science graduates for training in respiratory therapy at King Hussein Medical Center in Amman, Jordan. To refresh my own cardiac training, I joined Dr. Denton A. Cooley's service at THI as a fellow (1972–1973).

It is no exaggeration to say that Dr. Cooley deserves the credit for most of what I subsequently achieved. His simple, agile, confident operative style made heart surgery an immensely educational experience and gave me the confidence to use THI's methods and procedures as a model for ours in Syria. My fellowship at THI exposed me to a wide variety of cardiac conditions, enabled me to see how 20 to 30 surgical cases per day could be handled smoothly and efficiently, and gave me the opportunity to write a few papers. Perhaps the most important of these described Dr. Cooley's biatrial approach to excising atrial myxoma,10 a procedure that we later applied effectively in our center.9

Launching the Project

In 1973, Syria was at war with Israel. This set our project back appreciably, but in 1975 we finally managed to convert a wing of the hospital into an 11-bed cardiovascular surgical unit. The unit was administratively connected to the Ministry of Higher Education and was relatively autonomous from the Damascus University and hospital administrations. It had a separate budget and fewer bureaucratic delays in procuring equipment and recruiting and training personnel.

In January 1976, we resumed open-heart surgery at the new hospital unit. Those were tough times. I remember that I frequently had to sleep in the ICU when a patient was in unstable condition. When a death occurred after an operation, the word spread, and we would have trouble convincing the next patient on the list to sign the permission to operate. Nevertheless, we gradually gained the confidence of Syrian doctors and patients and began performing more complex surgical procedures. Our waiting list grew by the day.

With an independent unit, we had better rapport with our patients; with an independent operating room, blood bank, and sterilization and intensive care services, we were better able to deal with most of the difficulties that we faced than we had been when we were part of the general hospital. Soon after launching our unit, we were able to perform 1 open-heart and 1 closed-heart procedure per day. Meanwhile, I continued to perform thoracic and vascular surgery at the general hospital.

Our New Terrain

As early as 1977, it was obvious that our small hospital unit would not be sufficient to accommodate the many patients who needed heart surgery in Syria. I convinced the Minister of Higher Education to allocate to our purposes the top floor of a new hospital building that had originally been designed for nuclear medicine, and I procured a loan from the American Agency for International Development to fully equip the center. In 1980, we moved to the new location, which had a 25-bed capacity. We gradually increased our productivity to 2 open-heart procedures per day, tackled increasingly complex congenital and acquired cardiac conditions, and began training young heart surgeons.

In 1982, I took a furlough from Damascus University in order to work with Dr. Elias S. Hanna in San Francisco for 18 months. This helped me to become familiar with new developments in my specialty and enabled me to publish several papers, perhaps the most important of which was the first report in the medical literature on sequential grafting of the internal mammary artery.11

I returned to Syria in 1983 and resumed my position as director of the Damascus University Cardiovascular Surgical Center. In 1990, we were able to expand our share of the building to 2 floors and thus increase our bed capacity to 50, with a 10-bed ICU. Our productivity increased from 10 surgical cases per week in the early 1980s to more than 30 in 2002. International collaboration, such as with the Clinique de Genolier (Genolier, Switzerland), Le Centre Chirurgical Marie Lannelongue (near Paris, France), the Policlinico San Donato (Milan, Italy), and the Elias S. Hanna Cardiovascular Foundation (San Francisco),12 enabled our team to stay abreast of major advances in cardiac surgical techniques, anesthesia, perfusion, and intensive care, and to participate in modest clinical research.

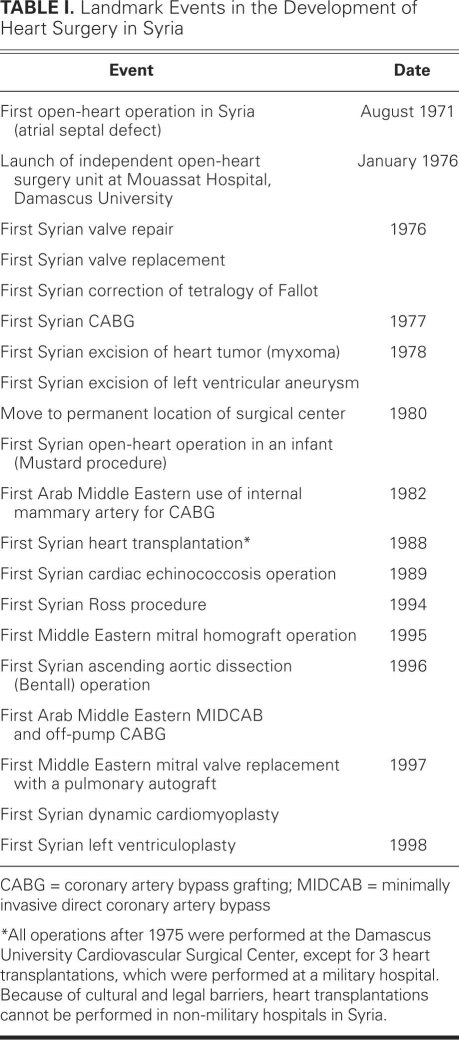

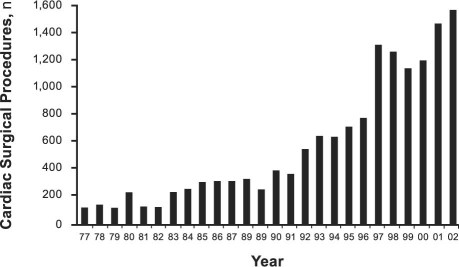

Table I summarizes the landmark events in our progressive development, and Figure 6 shows the trends in our surgical productivity over the years. We have treated approximately 1,600 patients annually since 2002.

TABLE I. Landmark Events in the Development of Heart Surgery in Syria

Fig. 6 Graph shows the number of open-heart procedures performed at Damascus University Cardiovascular Surgical Center, 1977–2002.

I reached retirement age in 2006 and left my position as director of the center, but I kept my university tenure, and I continue to perform surgery and serve as a consultant. Our unit has been enlarged to encompass all 6 floors of our building, because the nuclear medicine department was moved to another location. Plans are under way to build an addition to the existing building, which should enable us to double our caseload in 2 years. By virtue of an Italian loan, a separate 16-bed unit with a 9-bed ICU has been set up in the adjacent Children University Hospital. This unit, devoted to infant cardiac surgery and administratively connected to our center, is due to be launched later in 2011. We now have a team of 12 heart surgeons and 10 cardiac surgery residents, and we have established a formal 6-year residency program in cardiac surgery. Almost all of the 110 cardiac surgeons currently active in Syria have either passed through or completed their training at our center.

My chief area of interest in my last years as director lay in finding a suitable mitral valve substitute for young rheumatic patients with irreparable valves—a substitute that can resist early degeneration and eliminate the need for lifelong anticoagulation, which is so impractical to sustain in Third World countries.13 With the help of Mr. Donald Ross, we revived his original idea of replacing the mitral valve with a pulmonary autograft. Our center currently has the widest experience in the world in performing this operation.14,15

In 1992, we founded the Syrian Cardiovascular Association, which has since hosted 10 biennial international meetings and 15 symposia and has become an official member of the European Society of Cardiology.

Concluding Thoughts

While working in San Francisco in the early 1980s, I entertained the thought of staying in America permanently. I was living in one of the most beautiful cities in the U.S., my wife was American, and I had a nice home and a promising career. I am now glad that I decided to return and continue the job that I had started in Damascus a decade earlier.

I was told at the time that there were perhaps 100 cardiac surgeons in San Francisco. Had I stayed, the number of surgeons would merely have increased by one. I like to believe that by deciding to return to my native country instead, my efforts made a big difference in the treatment options available to the Syrian cardiovascular patient, and in the development of my specialty in Syria. This satisfaction and sense of accomplishment cannot be valued in any currency. My advice to young specialists who face a similar all-important life decision is to accept the challenge of returning home, because I believe that the rewards far outweigh the drawbacks.

Insights from My Experience

I can summarize the insights from my experience as follows:

Persevere. I can't count the number of times when, during the course of my 40-year journey, I almost decided to quit and fly to the U.S. out of frustration with the bankrupt status quo, with the bureaucracy that plagues emerging societies, and with the difficulties in dealing with various people in charge who seemed not to appreciate the significance of our mission.

My advice to young surgeons who return home is this: when you experience hopelessness (and you will), don't give up; keep trying. Sooner or later, you will find a way to overcome your temporary predicament.

Don't Compromise on the Basic Issues. A sufficient degree of independence from official and bureaucratic interference, the ability to hire the best-qualified personnel, and the wherewithal to purchase the best equipment should be nonnegotiable.

Plan to Grow and Expand Continuously. This is true in both volume and types of surgical procedures. A clinical entity at a standstill is always in danger of stagnating, especially if you are working in a region of the world that is relatively cut off from mainstream events in your specialty. To grow and expand, collaborate with as many established medical centers as possible that are active in your areas of interest.

Aim High. Working in a developing region of the world does not prevent you from advancing your specialty and doing your share of research. I recommend that you concentrate on clinical areas that are important in your country: this is how you can best help your countrymen, as well as break new ground in your specialty.

Your decision as a foreign graduate to return home after completing cardiothoracic surgical training in a Western country is personal, and no one can make it for you. However, I believe that by choosing to come home, you would be opting for a more meaningful existence—adding life to your years, not just years to your life. Although the road to establishing a sophisticated specialty such as cardiothoracic surgery in a developing country may be bumpy and full of daunting twists and turns, I am convinced that the goal is worth the effort.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge Prof. Fuad Shaban and Mrs. Mary Shaban for reviewing the text, and Ms Randa Jaafari for preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Sami S. Kabbani, MD, Damascus University Cardiovascular Surgical Center, Mezza St., P.O. Box 2837, Damascus, Syria

E-mail: dam-uncv@net.sy

References

- 1.Chin J, Bashour T, Kabbani S. Tetralogy of Fallot in the elderly. Clin Cardiol 1984;7(8):453–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kabbani SS, Ramadan A, Kabbani L, Sandouk A, Nabhani F, Jamil H. Surgical experience with cardiac echinococcosis. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2007;15(5):422–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bashour T, Kabbani SS, Jokhadar M, Hanna ES, Cheng TO. Constrictive pericarditis. Medical vs surgical treatment. Cardiovasc Rev Rep 1983;4(10):1337.

- 4.Kabbani SS, Bashour T. Mitral valve surgery in Syria. In: Bircks W, Ostermyer J, Schulte HD, editors. Cardiovascular surgery 1980: proceedings of the 29th International Congress of the European Society of Cardiovascular Surgery. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1981. p. 92–6.

- 5.Kabbani SS, Bashour T, Dunlap R, Hanna ES. Mitral stenosis with severe pulmonary hypertension. Tex Heart Inst J 1982;9(3):307–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bashour T, Kabbani S, Cheng TO. Continuous precordial murmur due to congenital fistula between the femoral artery and the superior vena cava. Chest 1978;74(2):226–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bashour T, Kabbani S, Cheng TO. Congenital bronchopleurocutaneous fistula. Chest 1981;79(4):489. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bashour TT, Kabbani S, Sandouk A, Cheng TO. Double-chambered right ventricle due to fibromuscular diaphragm. Am Heart J 1984;107(4):792–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kabbani SS, Jokhadar M, Meada R, Jamil H, Abdun F, Sandouk A, Nabhani F. Atrial myxoma: report of 24 operations using the biatrial approach. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58(2): 483–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kabbani SS, Cooley DA. Atrial myxoma. Surgical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1973;65(5):731–7. [PubMed]

- 11.Kabbani SS, Hanna ES, Bashour TT, Crew JR, Ellertson DG. Sequential internal mammary-coronary artery bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983;86(5):697–702. [PubMed]

- 12.Hanna ES, Kabbani SS, Bashour TT. Open-heart surgery–an American experience in Shanghai. West J Med 1985;143(2): 266–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kabbani SS. Is an optimal mitral substitute within reach? Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69(6):1651–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kabbani SS, Jamil H, Hammoud A. Technique for replacing the mitral valve with a pulmonary autograft: the Ross-Kabbani operation. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72(3):947–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kabbani S, Jamil H, Nabhani F, Hamoud A, Katan K, Sabbagh N, et al. Analysis of 92 mitral pulmonary autograft replacement (Ross II) operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134(4):902–8. [DOI] [PubMed]