Abstract

Objectives

To examine the prevalence of risk factors for diabetes and its complications in the Co-operation Council of the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) region.

Design

Systematic review.

Setting

Co-operation Council of the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) states (United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait).

Participants

Residents of the GCC states participating in studies on the prevalence of overweight and obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.

Main outcome measures

Prevalences of overweight, obesity and hyperglycaemia, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Results

Forty-five studies were included in the review. Reported prevalences of overweight and obesity in adults were 25–50% and 13–50%, respectively. Prevalence appeared higher in women and to hold a non-linear association with age. Current prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance was estimated to be 10–20%. Prevalence appears to have been increasing in recent years. Estimated prevalences of hypertension and dyslipidaemia were few and used varied definitions of abnormality, making review difficult, but these also appeared to be high and increasing,

Conclusions

There are high prevalences of risk factors for diabetes and diabetic complications in the GCC region, indicative that their current management is suboptimal. Enhanced management will be critical if escalation of diabetes-related problems is to be averted as industrialization, urbanization and changing population demographics continue.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus, particularly type 2 diabetes mellitus, is well documented.1 Type 2 diabetes is currently estimated to account for over 90% of the global diabetes burden.2 Together with similar trends in other non-communicable diseases, it leads to risks not only for individuals, but for health systems, social systems, and state economies. This risk is in part to do with an anticipated relatively dramatic rise in countries with relatively young populations, and still developing economic infrastructure, as they undergo the predicted increases in prevalence of diabetes associated with changes in lifestyle and economic development, and population growth. Even when based on changes in population size and demography alone,3 the highest predicted future increases are expected in the International Diabetes Federation's ‘African’ region (estimated 98.1% increase 2010–2030), followed by the ‘Middle East-North Africa’ region (estimated 93.9% increase 2010–20304). The Middle East-North Africa region already has some of the highest rates of diabetes in the world. The countries of the Co-operation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) include those currently ranked 2, 3, 5, 7 and 8 for diabetes prevalence among the 216 countries for which data are available.4

This high prevalence in the GCC states is associated with higher prevalences of risk factors for type 2 diabetes in this region. The International Diabetes Federation suggests the following as risk factors for type 2 diabetes: age, obesity, family history, physical inactivity, race and ethnicity, and gestational diabetes. Of the modifiable risk factors, physical inactivity appears to have been surprisingly little studied in this region, although it is likely to be correlated with overweight and obesity, which have been relatively well studied.

We aimed to review the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the GCC region. We also aim to review the prevalence of potentially ‘pre-diabetic’ hyperglycaemia (measured either as impaired fasting glycaemia, impaired glucose tolerance or raised random glucose). We also examined hypertension and dyslipidaemia, which are risk factors for adverse outcomes in people with diabetes.5–7 Diabetes is complicated by various micro- and macro-vascular conditions and people with metabolic syndrome – a collective of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and hyperglycaemia8–12 – have a relatively higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease than those without.13 Due to the heterogeneity of studies identified on preliminary searching, there was no anticipated meta-analysis.

Methods

Review question

A literature search was used to identify material relevant to the following review question: What are the prevalences of overweight and obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in the GCC region?

Search strategy

We developed a systematic review protocol (available from the authors on request) using the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines.14 Medline and Embase were searched separately on 15 July 2009 and the search was repeated on 03 July 2010 (via Dialog and Ovid, respectively; 1950 to July week 1 2010, and 1947 to July 2010) using terms identified from PICOS deconstruction of the above review questions, and database- and manually- derived alternatives (Appendix 1). The search strategy was trialled, reviewed by independent professional colleagues (IW, KP) and updated before use. Further relevant studies were identified by searching the reference lists of the database-derived papers, contacting expert investigators, screening conference proceedings, citation searching and hand searching the International Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism and the Saudi Medical Journal, for the periods 1993–2009 and 2000–2010, respectively.

Selection of studies

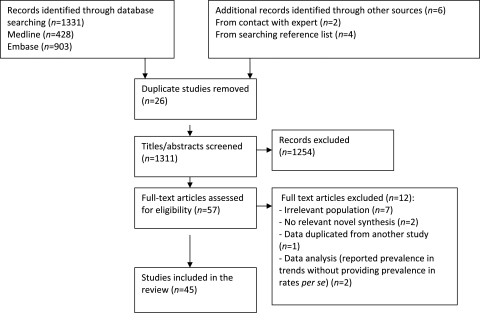

The search yielded 1331 studies. The titles and abstracts were evaluated by one reviewer to determine eligibility for full screening. All studies wherein overweight, obesity, body mass index (BMI), hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia were investigated were eligible for inclusion. No limitations on publication type, publication status, study design or language of publication were imposed. However, we did not include secondary reports such as review articles without novel data synthesis. The inclusion criteria required that the study population be of a GGC country, but otherwise all ages, sexes and ethnicities were included, resident and expatriate populations, urban and rural, of all socioeconomic and educational backgrounds. Studies of general, working, young, student, healthcare attending, and other populations were included. We did not specify diagnostic criteria for the studied conditions, but incorporated them into our data synthesis.

A total of 1331 studies were identified. The full texts of these studies were each considered by two reviewers (LA and McK). All studies of diabetic populations were excluded,15–17 and studies wherein people with diabetes had been excluded from the study population were excluded.18,19 Further exclusions were made on the basis that the studies were:

Of a type 1 diabetes population;22

Of a population outside the GCC region;23

Reported trends in prevalence, without providing prevalence rates per se;24,25

Duplications of data contained in other studies.26

The selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process

Data extraction/quality assessment

The data extracted from each study included data relating to: (1) methods (study design, recruitment, measurement tools, analysis); (2) participant characteristics; (3) setting; and (4) outcomes (those observed, their definitions, results of analysis). Study quality was assessed using a checklist adapted from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines.14 As the identified studies were relatively few and heterogeneous, no study was excluded on the basis of quality alone; rather the assessment was used to inform synthesis. Data extraction was performed, in duplication, by two reviewers (LA and AM), and disagreement regarding any study eligibility was resolved through consensus and seeking the opinion of the third reviewer (AM).

Data synthesis

Data synthesis included summarizing the results of the data extraction process, considering the strength of evidence relating to various questions formulated a priori (see the Results section), and examination of results inconsistent with our formed proposals. In the cases of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, synthesis was limited by the number of studies identified, and in these cases description and discussion suffices.

Results

Forty-five studies (43 papers) relating to risk factors and their prevalence were identified for review. All papers identified were journal articles published between 1987 and 2010. Five studies were carried out (where reported) and/or published in the late 1980s, 23 in the 1990s, and 15 in the last 10 years. Studies of various 20 Saudi,24–46, seven Kuwaiti,47–50 three Bahraini,51–53 eight Emirati,54–60 four Omani61–64 and one Qatari65 populations were included. All were cross-sectional studies; 23 of the general population, seven of primary care populations, four of schoolchildren, three of students, one of a young population, five of working populations. Women were exclusively studied in five cases, men in six. Sample size ranged from 215 to 25,337.

In addition to examining the prevalence of the particular risk factors in the GCC states, we were interested in the following:

Trends in prevalence across time;

Differences by country;

Trends in prevalence associated with age;

Sex differences;

Location (urban/rural) differences;

Prevalence in children.

Only in the cases of overweight and obesity, and hyperglycaemia were study numbers sufficient that reasonable conjecture regarding subgroups could be made. They are considered separately, for each risk factor, below.

Obesity/overweight

Thirty-three studies addressed the prevalence of overweight/obesity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of overweight/obesity prevalence data

| Dates of study | Population sampled | Country | Sample size | Population characteristics | Definitions | Results | Quality assessment checklist(*) (Y: Yes, N: No, NA: Not Applicable) |

Study limitations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) | Age (years; range unless specified) | Residency status; area(s) of residence | Overweight (if not 25 to < 30) | Obesity (if not ≥ 30) | Prevalence overweight (%) | Prevalence obesity (%) | ||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||||

| 1980– 198148 | PC | Kuwait | 1171 | 0 | 18 to >60 | Kuwaiti nationals | >25 | 59.2 | 32.2 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | Sample selection method not clear Limitation of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

|||

| 1980–198149 | PC | Kuwait | 2067 | 43.3 | 18 to >60 | Kuwaiti nationals | >25 | 21.7–69.4 (age- dependent) | as Al-Isa, 1997a (above) | 8.5–24.1 (age- dependent) | as Al-Isa, 1997a (above) | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Sample selection method not clear Limitation of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

|

| 1985–198827 | GP | KSA | 17892 | 48.5 | 18 to <61 | Saudi nationals | 30.7 | 28.4 | 14.2 | 23.6 | 1-Y, 2-N, 3-N, 4-N, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Sample selection method not clearly Data analysis not clear Educational/employment status of the sample not reported Limitation of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||

| NR28 | GP | KSA | 3171 | 45.9 | >15 | >27 in men, | >25 in women | 30.1 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Unconventional definition of obesity Selection methods of houses for sampling not clear Dates of study not clear Limitation of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 1991–199251 | GP | Bahrain | 290 | 47.2 | 20–65 | Urban/rural mix | 26.3 | 29.4 | 16.0 | 31 | 1-Y, 2- Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Selection procedure not well described Statistical analysis not described Limitation of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||

| 1990–199329 | GP | KSA | 13177 | 52 | 15 to >60 | Saudi nationals | 33.1 | 29.4 | 17.8 | 26.6 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | The sample may not be truly representative for the general Saudi diabetic patients (sample randomly selected from National Epidemiological Household Study for Chronic Metabolic Diseases) Limitation of the study not discussed |

||

| 1990–199330 | PC | KSA | 3261 | 49.5 | 30–70 | Saudi nationals; urban/rural mix | 41.91 | 31.55 | 29.94 | 49.15 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

||

| 199231 | PC | KSA | 1385 | 0 | 16–70 | Urban/rural mix | 26.8 | 47.0 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3- Y, 4- Y, 5-N, 6- Some, 7-NA | Recruitment process not specified Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

||||

| NR54 | SP | UAE | 215 | 0 | 18–30 | Emirati nationals | 19 | 9.8 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-Some, 7-NA | The sample may not be truly representative for the general Emirate population (sample from UAE female university only) Limitation of the study not discussed clearly |

||||

| 199432 | PC | KSA | 1580 | 100 | >16 | Urban/rural mix | 34.8 | 28.6 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitation of the study not discussed | ||||

| 1993–199433 | Military hospital | KSA | 1485 | 46.1 | 18–91 | Saudi nationals | 40.1 | 31.5 | 21 | 40.5 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Specific population sampled Limitations of the study not discussed |

||

| 1993–199434 | WP* | KSA | 2990 | NR† | <25 to >60 | 94.7% Saudi nationals | 30.3 | 24.5 | 1-N, 2-N, 3-N, 4-N, 5-N, 6-Y, 7-NA | Sample selection methods not well described Potential of selection bias samples misses more complicated cases ('referred to hospital clinic') Sampled population relatively unrepresentative of general population(National Guard employees and dependants) Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

||||

| 1993–199447 | PC‡ | Kuwait | 1705 | 0 | 18 to >60 | Kuwaiti nationals | >25 | 72.9 | 40.6 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

|||

| 1993–199448 | PC§ | Kuwait | 3435 | 50.3 | 18 to >60 | Kuwaiti nationals | >25 | 44.3–75.1 (age- dependent) | as Al-Isa, 1997a (above) | 17.1–35.6 (age- dependent) | as Al-Isa, 1997a (above) | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

|

| NR55 | SC | UAE | 4075 | 43.9 | 6–17 | UAE nationals | Overweight 85th–95th percentile Obesity >95th percentile or BMI >30 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 1-Y, 2- Incomplete methods of selection, 3- Y 4- Y, 5-N, 6- partially, 7-NA | Method of study sample recruitment not clear Lack of standardization Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

|

| NR35 | SC | KSA | 14660 | 42.0 | 14–70 | Saudi nationals | 27.23 | 25.20 | 13.05 | 20.26 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-N, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Data analysis was not discussed clearly Study limitations not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||

| NR52 | GP | Bahrain | 2013 | 58.0 | Men 40–59 Women 50–69 | Bahraini nationals | 39.9 | 32.7 | 25.3 | 33.2‡‡ | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Method of blood sampling not clear |

||

| 1998 – 199956 | SC | UAE | 898 | 0 | 11–18 | Overweight: 85th –95th percentile Obesity: > 95th percentile | 14 | 9 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | Results might be biased as all the measurements were collected by one investigator only Limitations of the study not discussed |

||||

| 1998–200050 | WP** | Kuwait | 9755 | 48.0 | Mean age + SD: Women 33.3 + 11.6; Men 29.2 + 8.2 | Kuwaiti nationals | 38.3 | 32.8 | 27.5 | 29.9 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3-N, 4-N, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Sample recruitment method not discussed clearly Data analysis not clear Study limitations not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||

| 1998 – 199957 | SC | UAE | 4381 | 49.6 | 5–17 | 48.0% UAE citizens; 81.7% urban | IOFT criteria | 19.2 | 19.8 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Secondary data analysis Limitations of the study not discussed |

|

| 1998–200049 | WP** | Kuwait | 740 | 100 | 45–80 | Kuwaiti nationals | 37 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-Some, 7-NA | Sample recruitment method not discussed clearly Study limitations not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

|||||

| 1999–200066 | WP†† | Kuwait | 3282 | 85 | 54 % <40 | 62% Kuwaiti nationals | 48 | 27 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Data on the population characteristics including age and ethnic origin was limited Details on the method of blood sampling was not clear Study limitations not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 1999–200058 | GP§ | UAE | 724 | 0 | 20 to >60 | UAE nationals | 30–40 | 27 | 16 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Potential of sample selection bias (recruitment via students at one university) Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

|||

| 200061 | GP | Oman | 5838 | 49.8 | 20 to >80 | Omani nationals; urban/rural mix | 28.9 | 18.5 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Procedure for determining BMI not reported Steps taken to minimize bias were not discussed Limitations of the study were not discussed |

||||

| NR36 | GP | KSA | 11208 | 41.3 | 20–70 | Saudi nationals | 32.82 | 29.09 | 15.21 | 23.97 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3- Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Method not discussed clearly Sample selection was not clear Study limitations were not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias were not discussed |

||

| 1999– 200059 | GP | UAE | 5844 | 42.8 | 20 to >65 | UAE residents; '80% urban' | 48 | 35 | 24 | 40 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Sampling method of purposely biased population 'non-institutionalized' Steps taken to minimize bias were not discussed |

||

| 200062 | GP | Oman | 5847 | 48.8 | 20 to >60 | 900 urban; 4947 rural | 19.1 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-Y, 7-NA | Secondary data collection Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

|||||

| 2001–200237 | SP | KSA | 701 | 100 | Mean age 21.7 years | Saudi nationals | 31 | 23.3 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | The selected sample might not be representative for the whole population ( the selected sample might not be representative sample ) Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

||||

| 2001–200267 | YP | KSA | 894 | 100 | 12–20 | 13.8 | 20.5 | 1-Y, 2- Incomplete, 3-N, 4- Y, 5-N, 6- N, 7, NA | Sampling method not discussed clearly Data analysis not clear |

|||||

| 2004–200560 | PC | UAE | 817 | 49.3 | 20 to >60 | UAE nationals | 28.3 | 46.5 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-N, 5-Y, 6- N, 7-NA | Statistical analysis was not described clearly Study limitations not discussed |

||||

| NR38 | SP | KSA | 241 | 100 | Mean age + SD: 21.2 + 1.3 | 29.9 | 16.6 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-N, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Data analysis was not described clearly Study limitations were not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias were not discussed |

|||||

| 2007 – 200865 | GP | Qatar | 1117 | 51.1 | 20–59 | Urban/semi-urban | 31.9 | 45.2 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | The selected sample might not be representative sample As the recruitment of subjects is from primary healthcare centres, there may be a possibility that this sample is biased | ||||

| 200539 | SC | KSA | 19317 | 50.8 | 5–18 | Saudi nationals | WHO 2007 criteria | 24.8 | 28.4 | 10.1 | 8.4 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not clear |

|

Summary of cross-sectional studies investigating the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the GCC region

*Employees of Saudi National Guard and dependents

†‘Mostly settled tribal men’

‡Attendees at primary healthcare centres with minor complaints, plus accompanying persons

§All subjects recruited via family member at UAE University

**Adult attendees of the Kuwait Medical Council and Public Authority for Social Security (government employed/retired population)

††Employees of Kuwait Oil Company

‡‡Age-adjusted data

(*)Quality assessment checklist adapted from the Centre of Reviews and Dissemination guidelines (CRD) for non-randomized studies:

(1) Was the aim of the study stated clearly?

(2) Was the methodology stated? And was it appropriate?

(3) Were appropriate methods used for data collection and analysis?

(4) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

(5) Were preventive steps taken to minimize bias?

(6) Were limitations of the study discussed?

In systematic review, was search strategy adequate and appropriate?

PC = primary healthcare-registered population; GP = general population; WP = working population; SC = schoolchildren; SP = student population; YP = young population

Overweight and effect of date and country

The reported prevalence rates of overweight (BMI 25 to <30) in adults ranged from 26.3–48% in men, and 25.2–35% in women. Although higher values are displayed in Table 1, they have been scaled down for/omitted from comparison as either the definition of overweight used included the typical definition of obesity, or the prevalence was given only by age group, allowing the possibility that similarly high figures were masked in the age-non-specific data of other studies. A lower value has also been omitted where the study population was particularly young.54 Within these ranges, the data were fairly even distributed between the limits, and reported sex-non-specific prevalences were also consistent with these figures. The data showed no obvious trends or anomalies by date or country, although the data from Oman (two studies, reporting combined overweight/obesity rates) suggest prevalence there may be relatively low.

Obesity and effect of date and country

The reported general prevalence rates of obesity (defined as BMI ≥ 30) in adults ranged from 13.05–37% in men, and 16–49.15% in women (again a lower value has been omitted where the study population was particularly young54). As for the overweight data, the reported sex-non-specific data are consistent with these figures, and potentially excepting the Omani data, show no obvious trends or anomalies by date or country.

Obesity and overweight and age

Age as a potential predictor of prevalence of overweight/obesity was considered in eight studies (of adult populations), and the results were tested for significance in two cases. These latter studies demonstrated correlation between overweight/obesity and age,36 and a significantly higher mean BMI in a 45–54-year age group versus a 55–64-year age group.49 Similarly, all remaining studies indicated that prevalence increased with age to a threshold level (variably between 30–40 and 50–60 years (potentially younger in women) after which it began to fall, or fluctuate.27,33,47,48

Obesity and overweight and sex

Most studies reported prevalence rates by sex, but only four tested for differences. Of these four, in all cases but one, BMI/prevalence of obesity and overweight was higher in women,35,54,60 and where overweight was higher in men,36 the combined prevalence of overweight/obesity remained higher in women. In the remaining studies, prevalence of obesity, and the combined prevalence of overweight/obesity was again always higher in women, although in some cases the ‘difference’ was slight.

Obesity and overweight and residential environs

Six studies considered prevalence in urban versus rural populations. In three, mean BMI was found to be significantly higher in rural populations.31,33,34 In a further two studies, prevalence of both overweight and obesity were significantly lower in rural regions.29,30 This trend (with one subgroup exception – female obesity) was also observed where significance of differences was unclear.51

Obesity and overweight in national/expatriate populations

Only one study considered prevalences in national versus expatriate populations. This reported that the combined prevalence of obesity and overweight was higher in Kuwaitis versus non-Kuwaitis.66

Obesity and overweight in children

In keeping with the association with age, prevalences in children/young people (<20 years) are lower than those in adult populations. However, there is a greater indication that prevalences in the younger populations are increasing. Single figure prevalences were reported until around 2000, and have not been observed since. The most recent reports (suggesting prevalences of combined overweight and obesity >30%) provide rates comparable to those in adults. Although less considered, there is again evidence for higher prevalences with increasing age in these relatively young populations,47,56,67 in urban areas57 and in girls.39,57

Hyperglycaemia

Seventeen studies28,29,40–45,49,50,53,59,61,63–65 reported on the prevalence of hyperglycaemia, 12 studies as impaired glucose tolerance,28,29,40–44,53,63–65 three studies as impaired fasting glucose45,59,61 or a high random capillary glucose (>10 mmol/L).49,50 A summary is provided in Table 2. Generally, impaired glucose tolerance was defined as venous plasma glucose ≥7.8 and <11.1 mmol/L 2 h post glucose loading. Where the World Health Organization 1980 criteria were used, however, the impaired glucose tolerance would be defined as venous plasma glucose 8.0 and 11.0 mmol/L 2 h post glucose loading, and the study of Al-Moosa et al.62 involved capillary whole blood rather than venous plasma samples (Table 2). Impaired fasting glucose was consistently defined as a fasting venous plasma glucose ≥6.1 and <7.0 mmol/L. The studies of random capillary blood glucose and impaired fasting glucose are so few that interpretation is difficult. Additionally, the random glucose measurement figures are likely to include instances of transient/‘stress’ hyperglycaemia. Nevertheless, both are potentially consistent with the impaired glucose tolerance results.

Table 2.

Summary of hyperglycaemia prevalence data

| Dates of study | Country | Population sampled | Sample size | Participant characteristics | Diagnostic criteria | Results (prevalence; %) | Quality assessment checklist(*) (Y: Yes, N: No, NA: Not Applicable) |

Study limitations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) | Age range (years) | Residency status; area(s) of residence | IGT | Hyper-glycaemia | IFG | IGT | Hyper-glycaemia | IFG | ||||||

| NR40 | KSA | WP* | 1385 | 100 | <15 to >65 | Saudi nationals; rural | WHO 1980 | 0.2 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3- Y, 4- Y, 5-N, 6-Some, 7-NA | Sampled population relatively unrepresentative of general population Recruitment process not specified |

||||

| NR28 | KSA | GP | 5222 | 53.1 | 15 to >55 | WHO 1980 | 1.1 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Sampling method not discussed clearly Limitations of the study not discussed |

|||||

| 198941 | KSA | GP | 1419 | 49.4 | 10 to >60 | 98% Saudi nationals; ‘semi-urban–rural' | 2-h fasting post-meal CBG 7.8–11 mM | 3.7 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Method not described clearly Limitations of the study not discussed |

||||

| 199142 | KSA | GP | 2060 | 48.5 | 14 to >60 | Saudi nationals | WHO 1980/ 1985 | Men 0.6 Women 1.2 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 199143 | KSA | GP | 23493 | 46.1 | 2–70 | Saudi nationals | WHO 1980/ 1985 | Men 0.49 Women 0.9 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-Some, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 1990–199329 | KSA | GP | 13177 | 52 | 15 to >60 | Saudi nationals | WHO 1985 | Urban men 10 Rural men 8 Urban women 11 Rural women 8 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitation of the study not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 199163 | Oman | GP | 5096 | 41.9 | 20 to >80 | Urban/rural mix | WHO 1985 | Men 8.1 Women 12.9 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed | ||||

| 199164 | Oman | GP | 4682 | 42.8 | >20 | Urban/rural mix | WHO 1985/ ADA 1997 | WHO criteria 10.5 ADA criteria 5.7 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Study limitations not discussed Data on the steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 1995–199653 | Bahrain | GP | 2002 | 58.6 | Men 40–59 Women 50–69 | Bahraini nationals | WHO 1985 | 17.9 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Method of blood sampling not clear | ||||

| NR44 | KSA | GP | 25337 | 46.2 | <14 to >60 | Saudi nationals | WHO 1980/ 1985 | 0.62 | 1-Y, 2- Incomplete, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Method not described completely Some data on the participants characteristics such as ethnicity and co-morbidities not discussed |

||||

| 1995–200045 | KSA | GP | 16197 | 47.6 | 30–70 | Saudi nationals | ADA 1997 | 14.1 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete, 3-Y, 4-N, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | The method was not described clearly Data analysis was not discussed clearly |

||||

| 1998– 200050 | Kuwait | WP† | 9755 | 48 | 18–80 | Kuwaiti nationals | random CBG > 10.0 mM | Males: 8.25 Females: 3.62 | 1-Y, 2-Incomplete (e.g. data collection), 3-N, 4-N, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Data collection not clear Method not described clearly |

||||

| 1998–200049 | Kuwait | WP† | 703 | 100 | 45–80 | Kuwaiti nationals | random CBG > 10.0 mM | 26 | 1-Y, 2-incomplete, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Method not discussed completely Study limitations not discussed Steps taken to minimize bias not discussed |

||||

| 1999–200059 | UAE | GP | 5844 | 42.7 | 24 to >65 | UAE residents‡; '80% urban' | WHO 1999 | WHO 1999 | Males: 4.5 Females: 8.0 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-N, 7-NA | Selection of subjects intentionally biased towards UAE citizens | |||

| 200061 | Oman | GP | 5838 | 49.8 | 20 to >80 | Omani nationals; urban/rural mix | FPG > 6.1 and < 7 mM | Males:7.1 Females: 5.1 |

1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-N, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed | ||||

| 2005–200646 | KSA | GP | 2396 | 49.1 | 18 to >70 | UAE nationals; urban | WHO 1999 | 20.2 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-N, 6-Y, 7-NA | Limitations of the study not discussed | ||||

| 2008–200965 | Qatar | PC | 1117 | 51.1 | 20–59 | Urban/ ‘semi-urban’ | WHO 2006 | 12.5 | 1-Y, 2-Y, 3-Y, 4-Y, 5-Y, 6-Some, 7-NA | The selected sample might not be representative sample As the recruitment of subjects is from primary healthcare centres, there may be a possibility that this sample is biased | ||||

Summary of cross-sectional studies investigating the prevalence of (non-diabetic) hyperglycaemia in the GCC region

*Government/municipal salaried workers

†Adult attendees of the Kuwait Medical Council and Public Authority for Social Security (government employed/retired population)

‡Selection of subjects intentionally biased towards UAE citizens

(*)Quality assessment checklist adapted from the Centre of Reviews and Dissemination guidelines (CRD) for non-randomized studies:

(1) Was the aim of the study stated clearly?

(2) Was the methodology stated? And was it appropriate?

(3) Were appropriate methods used for data collection and analysis?

(4) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

(5) Were preventive steps taken to minimize bias?

(6) Were limitations of the study discussed?

(7) In systematic review, was search strategy adequate and appropriate?

IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; WP = working population; GP = general population; PC = primary health care-registered population

Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and age

Broadly speaking, the relatively comprehensive study of impaired glucose tolerance is suggestive of a recent and ongoing increase in prevalence, with the latest published figures suggesting rates of perhaps 10–20% in the adult population. Although there are some inconsistent figures (Table 2), we consider that these could be accounted for by a combination of changes in prevalence across time and the ages of the studied populations. The studies of El-Hazmi et al.44 in particular reports an inconsistently low figure, but their sample was 39.1% children and the authors report a significantly higher prevalence with increasing age, although we could not access the full data and the statistics were not described. Similarly, the other relatively young populations are those wherein reported prevalences are relatively low. Furthermore, of all studies reviewed (including those of random blood glucose and impaired fasting glucose), five considered the effect of age on prevalence.42–44,49,50 All found the prevalence was higher with advancing age, and in all cases where tested (three cases), the relationship was found to be significant.43,49,50

Prevalence of hyperglycaemia by country

There was no obvious discrepancy in prevalence by country, but the number of studies available prohibited a reasonable comparison.

Prevalence of hyperglycaemia by sex

Thirteen studies reported differential prevalence rates by sex, although not all considered the strength of sex differences. The majority of studies (10) suggested a higher prevalence in women.29,41–43,45,46,53,59,63,65 Two demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence.41,59 Conversely, two studies50,61 showed a higher prevalence in men (one significantly so61), and one demonstrated no sex difference.45

Urban/rural residence and prevalence of hyperglycaemia

Only one study reported prevalence according to urban versus rural residence.29 Prevalence was higher in urban areas.

Prevalence of hyperglycaemia by residential status

No studies reported on effects of ethnicity, or on the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in national versus expatriate populations.

Hypertension and dyslipidaemia

Only few of the identified studies investigated the prevalence of hypertension34,46,59,60,62,65 and dyslipidaemia.34,49,62,66 Moreover, variable or ill-defined definitions of the diagnosis were used in each case.

Hypertension

We identified eight studies that included an assessment of hypertension.30,34,46,59,60,62,65,66 The definitions of hypertension employed ranged from ≥140/≥90 mmHg to >160/95 mmHg, and variably included those on antihypertensive medication. Additionally, one study34 depended upon a previous (undescribed) diagnosis. Reported rates of hypertension ranged from 6.6–33.6%. Potentially prevalence has been increasing since 1993–1994 (when the first identified studies were undertaken).

Dyslipidaemia

Dyslipidaemia was considered in six studies.34,46,49,50,62,65 Dyslipidaemia was defined as: cholesterol ≥5.2 mmol/L, cholesterol >5 mmol/L, high density lipoprotein <1.0 mmol/L, low density lipoprotein >4.1 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥2.3 mmol/L, or a previous (undescribed) diagnosis. Reported rates of dyslipidaemia ranged from 2.7–51.9%. This relatively large range is potentially partially due to increasing rates across recent years, to consideration of different aspects of the lipid profile in different studies and to differing definitions of abnormality. Additionally, in the study reporting the very lowest prevalence,34 diagnosis was established by ‘previous diagnosis’ alone, and thus allowed no assessment of the extent of undiagnosed cases.

Discussion

We found the prevalence of overweight to be 25–50%, obesity 10–50%, relatively high in women and higher with advancing age to threshold levels between 30–40 and 50–60 years. Prevalence was also found to be high in children, and appeared to be increasing in this group. We estimated, from relatively recent reports, the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in adults (using impaired glucose tolerance as the outcome measure) to be approximately 10–20%. Prevalence of hyperglycaemia appears to have been increasing across recent years, and higher prevalence again showed an association with advancing age and female sex. There has been relatively little research of the prevalences of hypertension and dyslipidaemia in the GCC region and a lack of consistency in definitions used for study. Accordingly, estimates of prevalence vary: between 6.6–33.6% for hypertension, between 2.7–51.9% for dyslipidaemia, and it is unclear what additional factors may have impacted on these ranges.

Potentially, the prevalences of hypertension and dyslipidaemia are increasing, which would be in keeping with a more widespread trend.68–70 The increasing prevalence of hyperglycaemia is similarly in keeping with trends reported elsewhere. By contrast, we observed no obvious temporal trend in prevalence of overweight and obesity in adult populations, which is not in keeping with reports from elsewhere, and despite a relatively well established association with diabetes (both epidemiologically and pathophysiologically1,71–73) and pathophysiologically. Importantly, though, particular authors have noted a rising prevalence within the relatively well controlled environments of their own studies,47,48 and several of the reviewed studies did demonstrate correlation between BMI, and overweight and obesity, and diabetes or blood glucose concentration.28,35,50 Moreover, the observed prevalence of overweight and obesity by age, increasing with advancing age until a plateau or decline in middle and older age, is suggestive that overweight and obesity may be an important risk factor for diabetes.

We noted differences in the patterns of spread of diabetes and obesity and overweight in the GCC region. For example, the observed bias of obesity and overweight to the female population is not obviously replicated in the population distribution of diabetes (unpublished data), demonstrating that additional aetiological factors may hold important roles in the current expansion of the diabetes problem.

Implications

We consider the need for further study to identify the major contributory factors to the current diabetes problem in the GCC region, and of factors such as hypertension and dyslipidaemia that compound the risks of diabetes, an important outcome of our review. The limited number and heterogeneity of existing studies pose difficulties for targeting, designing and developing potential management strategies. The relatively high levels of hyperglycaemia, and obesity and overweight (and potentially of hypertension and dyslipidaemia) observed – and their possible rising prevalences – are indicative that current management is insufficient. The reviewed data are suggestive that age and urban residence may be risk factors for, at least, overweight/obesity and hyperglycaemia. Enhanced management is thus crucial to prevent escalation of the problems as urbanization and changing population demographics continue.

It would be useful to determine that the situation is similar across the various GCC states. This is likely but cannot be confirmed from the data reviewed here. If so, expansion of existing management strategies, and coordination of novel strategies, across the region, would probably be relatively successful and relatively cost-effective. The likely contribution made by overweight/obesity to the diabetes problem in the GCC region is suitable for management, at least in part, by primary preventative measures, which we anticipate would also be relatively cost-effective.

Limitations of study

We report above that individual studies included in our review demonstrated recent temporal trends in prevalence of overweight and obesity, even though this was not clear from our overview of studies. This is probably illustrative of the general heterogeneity of the reviewed studies. The studies reviewed were relatively few and distributed across many years. They were of varied population characteristics, in different regions of six countries, and the utilized definitions of particular risk factors were inconsistent. We were thus able to make only relatively crude observation, and could not provide measures of confidence in our outcomes. The quality of reporting of results in the examined studies was also variable. For example, many studies did not report confidence intervals or had missing data for key variables. This reinforces the need for authors of risk factors studies to use standard methods for reporting the results such as STROBE guidelines.

Although quality was variable, it was never alone a reason for exclusion. Quality was, rather, incorporated into building our estimations of ranges for normal versus abnormal among the results returned. This was difficult due to the wide variability in these results, and the potential for bias has implications for the strength of our proposals. In addition, we may have increased bias by duplication of included data, as it is anticipated that the female sample of one Al-Isa study47 is that included in the mixed sample of another,48 and the male sample of Jackson et al.49 that included in the sample of Jackson et al.50 Finally, all of our reviewed studies were published in English, although we had no language restriction. Hence, we may have limited capture of publications in other languages due to the databases we searched.

Conclusions

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the GCC region is high and the ages of those affected suggest it may be a relatively important factor in the growing diabetes burden in this region. Further study aimed at elucidating its relative contribution to the diabetes problem is desirable, but regardless the reviewed data are suggestive that implementation and enhancement of primary preventative strategies in particular would be useful in the management of type 2 diabetes in the GCC region. The current prevalences of hypertension and dyslipidaemia are unclear, but potentially relatively high compared to many other parts of the world. More comprehensive study of their prevalence is desirable, and standardization of definitions of these conditions will be important if further study is to be maximally useful. Primary preventative strategies may also be useful in managing these conditions.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This study was supported by sponsorship provided to Layla Alhyas by the United Arab Emirates Ministry of Research and Higher Education, Abu Dhabi. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

LA

Contributorship

LA created and revised the research strategy; LA and AMcK selected and assessed the quality of the studies, and analysed the data from the studies; all authors wrote and revised the paper

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for contributions from Igor Wei and Kate Perris who assisted with the electronic search strategy

Reviewer

Paramjit Gill

References

- 1.Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Shaw J Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 2001;414:782–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Fact sheet No 312 Diabetes. Geneva: WHO, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 4th edn. Brussels: IDF, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffner SM, Mykkanen L, Festa A, Burke JP, Stern MP Insulin-resistant prediabetic subjects have more atherogenic risk factors than insulin-sensitive prediabetic subjects: implications for preventing coronary heart disease during the prediabetic state. Circulation 2000;101:975–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gress TW, Nieto FJ, Shahar E, Wofford MR, Brancati FL Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. N Engl J Med 2000;342:905–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg IJ. Diabetic dyslipidemia: causes and consequences. J Clin Endo Met 2001;86:965–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Brussels: IDF, 2006. See http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Heart Association. Metabolic Syndrome. Dallas, TX: AHA, 2010. See http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4756 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation Diabet Med 1998;15:539–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balkau B, Charles MA Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med 1999;16:442–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander CM, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM, Haffner SM NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes. 2003;52:1210–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York, 2009. [accessed July 2010]. See http://www.yourk.ac.uk/inst/crd/systematic_reviews_book.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Sultan FA, Al-Zanki N Clinical epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Kuwait. Kuwait Medical Journal 2005;37:98–104 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali H, Bernsen R, Taleb S, Al-Azzani B Carbohydrate-food knowledge of Emirate and Omani adults with diabetes: results of a pilot study. Int J Diabetes Metabolism 2008;16:25–8 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Kaabi J, AL-Maskari F, Saadi H, et al. Assessment of dietary practice among diabetic patients in the UAE. Rev Diabet Stud 2008;5:110–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binhemd T, Larbi EB, Absood G Obesity in primary health care centres: a retrospective study. Ann Saudi Med 1991;11:163–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik M, Razig SA The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among the multiethnic population of the United Arab Emirates: a report of a national survey. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2008;6:177–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamadeh RR Noncommunicable diseases among the Bahrain population: a review. East Mediterr Health J 2000;6:1091–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Lawati JA, Mabry R, Mohammed AJ Addressing the threat of chronic diseases in Oman. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5:A99 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eapen V, Mabrouk AA, Sabri S, Bin-Othman S A controlled study of psychosocial factors in young people with diabetes in the United Arab Emirates. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1084:325–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamir O, Peleg R, Dreiher J, Abu-Hammad T, Abu-Rabia Y Cardiovascular risk factors in the Bedouin population: management and compliance. IMAJ 2007;9:652–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abalkhail B Overweight and obesity among Saudi Arabian children and adolescents between 1994 and 2000. East Mediterr Health J 2002;8:212–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Hazzaa HM Rising trends in BMI of Saudi adolescents: evidence from three cross sectional studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007;16:462–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Isa AN Prevalence of obesity among Kuwaitis: a cross-sectional study. Int J Obes 1995;19:431–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Othaimeen AI, Al-Nozha M, Osman AK Obesity: an emerging problem in Saudi Arabia Analysis of data from the National Nutrition Survey. East Mediterr Health J 2007;13:441–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fatani HH, Mira SA, El-Zubier AG Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in rural Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Care 1987;10:180–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Nuaim AR Prevalence of glucose intolerance in urban and rural communities in Saudi Arabia. Diabet Med 1997;14:595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Saif MA, Hakim IA, Harris RB, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of obesity and overweight in adult Saudi population. Nutr Res 2002;22:1243–52 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Shammari SA, Khoja TA, Al-Matoug MA, Al-Nuaim LA High prevalence of clinical obesity among Saudi females: a prospective cross-sectional study in the Riyadh region. J Tropical Med Hyg 1994;97:183–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Shammari SA, Khoja TA, Al-Matoug MA The prevalence of obesity among Saudi males in the Riyadh region. Ann Saudi Med 1996;16:269–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogbeide Do, Bamgboye EA, Karim A, et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity and its correlation with chronic diseases in Al-Kharj adult outpatients, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 1996;17:327–32 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Shammari SA, Nass M, Al-Maatouq M, Al-Quaiz J Family practice in Saudi Arabia: chronic morbidity and quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care 1996;8:383–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS Prevalence of overweight and obesity in diabetic and non-diabetic Saudis. East Mediterr Health J 2000;6:276–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Hazmi M, Warsy A Relationship between age and the prevalence of obesity and overweight in Saudi population. Bahrain Medical Bulletin 2002;24:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Turki Y Overweight and obesity among attendees of primary care clinics in a university hospital. Ann Saudi Med 2007;27:459–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inam SN Prevalence of overweight and obesity among students at a medical college in Saudi Arabia. JLUMHS 2008;7:41–3 [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Mouzan M, Foster PJ, Al-Herbish AS, Alsalloum AA, Al-Omer AA Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Ann Saudi Med 2010;30:203–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacchus RA, Bell JL, Madkour M, Kilshaw B The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in male Saudi Arabs. Diabetologia 1982;23:330–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abu-Zeid HA, Al-Kassab AS Prevalence and health care features of hyperglycaemia in semi urban-rural communities in Southern Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Care 1992;15:484–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS, Al-Swailem AR, et al. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 1996;16:381–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS, Barimah NA, et al. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the population of Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 1996;17:591–7 [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, Al-Swailem AR, Sulaimani R Diabetes mellitus as a health problem in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 1998;4:58–67 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Nozha M, Al-Maatouq M, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi S, Arafah M. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2004;25:1603–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saadi H, Carruthers SG, Nagelkerke N, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its complications in a population-based sample in Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;78:369–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Isa AN Changes in body mass index and prevalence of obesity among adult Kuwaiti women attending health clinics. Ann Saudi Med 1997;17:307–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Isa AN Temporal changes in body mass index and prevalence of obesity among Kuwaiti men. Ann Nutr Metab 1997;41:307–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson RT, Al-Mousa Z, Al-Raqua M, Prakash P, Muhanna AN Multiple coronary risk factors in healthy older Kuwaiti males. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56: 709–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson RT, Al-Mousa Z, Al-Raqua M, Prakash P, Muhanna AN Prevalence of coronary risk factors in healthy adult Kuwaitis. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2001;52:301–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Mannai MS, Dickers OJ, Morgan JB, Khalfan H Obesity in Bahrain adults. J R Soc Health 1996;16:30–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K Obesity among adult Bahraini population: impact of physical activity and educational level. Ann. Saudi Med 2001;21:183–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Mahroos F, McKelcue PM High prevalence of diabetes in Bahrainis. Diabetes Care 1998;21:936–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Musaiger AO, Radwan HM Social and dietary factors associated with obesity in university females students in United Arab Emirates. J R Soc Health 1995;115:96–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Haddad F, Al-Nuaimi Y, Little BB, Thabit M Prevalence of obesity among school children in UAE. Am J Hum Biol 2000;12:498–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al-Hourani HM, Henry JK, Lightowler HJ Prevalence of overweight among adolescent females in the United Arab Emirates. Am J Hum Biol 2003;15:758–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malik M, Bakir A Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children in the United Arab Emirates. Obes Rev 2007;8:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheikh-Ismail, Henry CJ, Lightowler HJ, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult females in the UAE. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009;60:26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malik M, Bakir A, Saad BA, Roglic G, King H Glucose intolerance and associated factors in the multi-ethnic population of the United Arab Emirates: results of a national survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;69:188–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baynouna LM, Revel AD, Nagelerke NJ, et al. High prevalence of the cardiovascular risk factors in Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates. Saudi Med J 2008;29:1173–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Lawati JA, Al-Riyami AM, Mohammed AJ, Jousilahti P Increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Oman. Diabet Med 2002;19:954–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Moosa S, Allin S, Jemiai N, Al-Lawati J, Mossialos E Diabetes and urbanization in the Omani population: an analysis of national survey data. Popul Health Metr 2006;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Asfour MG, Lambourne A, Soliman A High prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the Sultanate of Oman: results of the 1991. national survey. Diabet Med 1995;12:1122–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al-Lawati JA, Mohammed AJ Diabetes in Oman: comparison of 1997. American diabetes classification of diabetes mellitus with 1985 WHO classification. Ann Saudi Med 2000;20:12–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bener A, Zirie M, Janahi IM, Al-Hamaq OA, Musallam M Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population based study of Qatar. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;84:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al-Asi T Overweight and obesity among Kuwait oil company employees: a cross-sectional study. J Occupational Med 2003;53:431–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Rukban MO Obesity among Saudi male adolescent in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2003;24:27–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988. to 2004 J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1056–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hyre AD, Muntner P, Menke A, Raggi P, He J Trends in ATP-III-defined high blood cholesterol prevalence, awareness, treatment and control among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:548–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hossain P, Kawar B, Nahas ME Obesity and diabetes in the developing world – a growing challenge. N Engl J Med 2007;356:213–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Astrup A, Finar N Redefining type 2 diabetes: ‘Diabesity’ or ‘Obesity Dependent Diabetes Mellitus’? Obesity Reviews 2000;1:57–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Gard R Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation 2005;111:1448–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]