Abstract

Thyroid dysfunction is associated with cognitive impairment and dementia, including Alzheimer disease (AD). It remains unclear whether thyroid dysfunction results from, or contributes to, Alzheimer pathology. We determined whether thyroid function is associated with dementia, specifically AD, and Alzheimer-type neuropathology in a prospective population-based cohort of Japanese-American men. Thyrotropin, total and free thyroxine were available in 665 men aged 71–93 years and dementia-free at baseline (1991), including 143 men who participated in an autopsy sub-study. During a mean follow-up of 4.7 (SD: 1.8) years, 106 men developed dementia of whom 74 had AD. Higher total and free thyroxine levels were associated with an increased risk of dementia and AD (age and sex adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) per SD increase in free thyroxine: 1.21 (1.04; 1.40) and 1.31 (1.14; 1.51) respectively). In the autopsied sub-sample, higher total thyroxine was associated with higher number of neocortical neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. No associations were found for thyrotropin. Our findings suggest that higher thyroxine levels are present with Alzheimer clinical disease and neuropathology.

Keywords: Epidemiology, thyroid hormones, thyrotropin, total thyroxine, free thyroxine, dementia, Alzheimer disease, neuropathology, neuritic plaques, neurofibrillary tangles

1. Introduction

Clinical thyroid disorders are associated with cognitive impairment and dementia [12]. Experimental studies report thyroid hormones induce changes in amyloid precursor processing or deposition of amyloid-β [4, 17], the major component of the amyloid deposits found in the brain of cases of Alzheimer disease. This suggests there may be a role for thyroid hormones in the etiology of AD, the most frequent form of dementia.

In the past, several small case-control studies have been published, showing either no association [28, 34] or an association of hypothyroidism with AD [6, 13]. Conversely, a more recent case-control study showed sub-clinical hyper- rather than hypo-thyroidism was associated with a higher risk for AD [32]. These mixed findings may result from the methodological limitations of a cross-sectional study design, including bias in subject selection and retrospective assessment of thyroid function. To date, there are few prospective studies that have examined the association between thyroid function and AD. In the Rotterdam Study sub-clinical hyperthyroidism was associated with a higher risk for dementia and AD after a two-year follow-up period [16]. In the Rotterdam Scan Study, no association was found with AD during a five year follow-up period, although higher thyroid hormone levels were associated with markers of brain atrophy on MRI scans of non-demented elderly [10].

Findings of sub-clinical levels of thyroid dysregulation, in particular sub-clinical hyperthyroidism, with an increased risk of AD are of interest but need replication. In addition, it remains unclear how thyroid function is related to AD. Although thyroid dysregulation could be contributing to Alzheimer pathology it is also possible that it is merely a consequence of the disease process, reflecting sub-clinical disease. Studies with a longer follow-up for dementia with supporting data on neuropathological features of AD may give additional insight into the role of thyroid hormones in the Alzheimer process. With data from the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (HAAS), a longitudinal study that includes assessment of clinical dementia, as well as an autopsy sub-study of the cohort, we tested the hypothesis that higher levels of thyroid measures are associated with an increased risk of AD and neuropathological markers thereof.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

The baseline sample consisted of participants of the Honolulu Heart Program, a prospective cohort study carried out among Japanese-American men living on the Island of Oahu, Hawaii from 1965 onwards [30]. Participants were examined on three occasions between 1965 and 1971. Of the 4,676 survivors, 3,734 (80%) participated in a fourth examination between 1991 and 1993 as part of the HAAS. Between 1994–1996 and 1997–1999 two additional examinations were carried out (participation rates 84 and 75% respectively). Prevalent dementia was ascertained at examination 4 and incident dementia at examinations 5 and 6. In 1991, an autopsy program was instituted to study risk factors for, and disease correlates, of neuropathologic markers of brain disease. All participants gave written, informed consent at each examination. Family members gave permission for cases of dementia. The study protocol was approved by the Kuakini Medical Center institutional review board.

2.2 Dementia case finding procedures

Dementia and its subtypes were identified in a multi-step case-finding procedure, described in detail elsewhere [14, 33]. In brief, all participants underwent neuropsychological screening with the 100-point Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI), a measure of global function that has been validated in English and Japanese [31]. Diagnosis was based on neuropsychologic testing using the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease (CERAD) battery, a neurologic exam and an informant interview. Those with dementia received a work-up with neuroimaging (in 86%) and blood tests. All recognized subtypes of dementia were considered in the diagnostic consensus conference that included a neurologist and at least two other study investigators. Dementia was diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria [1], probable and possible AD according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer Disease and related Disorders Association criteria [20], and vascular dementia according to California Alzheimer Disease and Treatment Centers criteria [9]. The remaining subtypes included subdural hematoma, Parkinson disease, cortical Lewy body disease, Pick disease, and cause not determined. Among participants who received autopsy evaluation, approximately two-thirds of the clinical Alzheimer cases met CERAD neuropathologic criteria [21] for AD [24].

2.3 Autopsy sub-study

Procedures for autopsy and neuropathological examination have been described elsewhere [24]. At death, brains were fixed in formalin for a minimum of 10 days. After fixation, brains were weighed, the cerebellum and brainstem were removed from the cerebral hemispheres, and all were cut serially in the coronal plane at 1-cm thickness. Slices were examined for grossly apparent neuropathologic lesions, and the whole brain and slices were photographed. Tissue from four areas of neocortex (middle frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, middle temporal gyrus, and occipital cortex) and two areas of hippocampus (CA1 and subiculum) was used to prepare Bielschowsky silver-stained sections. Samples were evaluated by one of three neuropathologists who were blinded to clinical information. Senile plaques (SP) (diffuse and neuritic plaques), neuritic plaques (NP) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) were counted in five fields from the CA1 and subiculum of the hippocampus and five fields each from the four areas of neocortex. Counts were standardized to 1-mm2 field areas [23]. Fields were selected for counting from areas with the highest numbers of lesions, and the field with the highest count was taken to represent the cortical or hippocampal area. A neuropathological diagnosis of AD was based on CERAD criteria.[21] These criteria included a maximum NP count of at least 4 per mm2 for probable AD and at least 17 per mm2 for definite AD.

2.4 Thyroid status

At time of examination 4, fasting blood samples were collected and put on ice immediately. Within 30 minutes, serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at − 70° C. Thyroid hormones were assessed in a random sub-sample of 1001 men who participated in examination 4. Several biochemical markers of thyroid function were assayed, including thyrotropin, free thyroxine (fT4) and total thyroxine (T4). Thyrotropin, fT4 and T4 were all measured by chemiluminescence assays on a DPC2000 analyzer (Diagnostic Product Co., Los Angeles, CA). The thyrotropin assay had an analytical sensitivity of 0.004 µU/dL and an inter-assay precision of 3.8% at 1.3 µU/dL. The fT4 assay had an analytical sensitivity of 0.30 ng/dL and an intra-assay precision of 4.8% at 2.10 ng/dL. The T4 assay had an analytical sensitivity of 0.30 µg/dL and an intra-assay precision of 4.6% at 8.23 µg/dL.

Thyrotropin and fT4 serum levels were assessed to define thyroid status. Serum thyrotropin concentrations above the reference range (0.4 – 4.3 µU/dL) may indicate hypothyroidism and concentrations below the reference range may indicate hyperthyroidism. However, in these instances fT4 concentrations are usually within the reference range (0.85 –1.94 ng/dL). Whereas an isolated high thyrotropin level indicates sub-clinical hypothyroidism, isolated low thyrotropin levels may indicate sub-clinical hyperthyroidism but may be also due to non-thyroidal illness or drug effects [29]. Clinical hypothyroidism was defined as a concentration of serum thyrotropin above the upper limit of the reference range and fT4 concentrations below the lower limit of the reference range [25]. Clinical hyperthyroidism was defined as a concentration of serum thyrotropin below the reference range and fT4 concentrations above the reference range [25].

2.5 Covariates

The association between thyroid hormones and dementia or neuropathological markers may potentially be confounded by a number of variables affecting health status; further, vascular risk factors may play an important role in the etiology of AD [18], and are also related to thyroid function [5]. Therefore, we adjusted for the following variables: age at death (for the autopsy sub-study), educational level and depressive symptoms, albumin levels, body mass index (kg/m2) (BMI), total and HDL cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, smoking status (never, former, current) systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Use of thyroid medication and other drugs potentially changing thyroid hormone levels including beta-blocking agents and use of anti-arrhythmics at time of blood draw was also entered in the statistical models. APOE genotyping was performed at the Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Alzheimer Disease Research Center with restriction isotyping using a polymerase chain reaction protocol [15].

2.6 Statistical analysis

2.6.1 Incident Dementia

After exclusion of one participant with an unusually high level of fT4 (4.35 ng/dL) and otherwise normal levels of measured thyroid hormones, the analytical sample consisted of 1000 participants. Of 1000 participants with thyroid hormone assessments, 131 were demented at exam 4, and 204 participants died or refused further participation, leaving 665 participants at risk for dementia. After a duration of 3204 person years of follow-up (mean: 4.7 years, SD: 1.8 years), 106 participants developed dementia, of whom 74 had AD (including AD cases with contributing cerebrovascular disease). Of those 106 dementia cases, 71 were diagnosed at exam 5, and 34 at exam 6. Analysis of covariance adjusted for age was used to compare characteristics of participants according to tertiles of fT4 and to compare participants with and without thyroid hormone assessments at examination 4. No statistically significant differences in socio-demographic variables or cardiovascular risk factors were observed between participants in the sub-sample with thyroid hormone assessments and those without (data not shown).

To test the hypothesis that higher thyroid function is associated with an increased risk of dementia and AD, we analysed thyroid function in two ways. First, thyroid status was classified as high, normal, or low levels of thyrotropin. The normal thyroid group was the reference and consisted of subjects with thyrotropin levels within the reference range. Second, we expressed the continuous measures as unit of a standard deviation increase if the observed association was not obviously non-linear.

A Cox proportional hazards regression delayed entry model with age as the time scale was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for total dementia and AD (with and without cerebrovascular disease). Age of onset was assigned as the midpoint of the interval between the last examination without dementia and the first follow-up examination with dementia. Subjects who died or did not participate in subsequent follow-up examinations were censored as of the time of their last evaluation. Cox models are typically used when the time-to-event is measured continuously across participants. Because it is difficult to surveil and dementia onset is usually gradual, the mid-way point between two visits is typically used as a measure of time of onset. However, in essence, the time of onset and diagnosis are bounded by discrete study exams. We therefore reran the clinical dementia analyses with a discrete time analysis model. This approach did not change the results. We tested the Cox proportional hazards assumption by adding the interaction term between hormone level and age to the model. For AD, all the interaction terms for the different hormones were not significant (P-value for interaction ≥0.11).

2.6.2 Autopsy sub-sample

The analytical sample for the autopsy study is 143, only five of whom had high and four of whom had low thyrotropin levels. Therefore we did not examine differences in pathology among these sub-groups. Analysis of covariance adjusted for age was used to compare characteristics of the autopsy cases with participants who dropped out after exam 4 within the thyroid sample. Baseline characteristics of the included autopsy cases did not differ from those in the thyroid sample who dropped out after exam 4 (data not shown).

The distributions of NP and NFT counts are skewed. Using goodness to fit statistics we determined the distributions of the NFT and NP were best fit by a negative binomial distribution. This model assumes an outcome that is measured in discrete counts, and a coefficient is interpreted as a count ratio giving the relative ratio of [i.e., NP] counts in the cases vs. control group. As an example, a coefficient of 0.10 means the case has 10% higher count than the controls.

2.7.3 Adjusted analyses

In addition to adjusting for age we also adjusted for the socio-demographic, medical history and biochemical markers described above. All analyses were repeated after exclusion of participants with clinical hypo- (n = 5) or hyperthyroidism (n = 1) and thyroid medication (n = 5).

Finally, for dementia we repeated the analyses in strata of APOE genotype; we classified participants into those with and without an ε4 allele. Due to small numbers in the autopsy sub-study, these analyses were not stratified according to APOE status. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) [3] and SAS version 8 (SAS, Cary, NC) [2].

3. Results

The sample included 615 (92.5%) participants with normal thyrotropin levels. Of these, 596 also had normal fT4 levels, 14 had low and 5 had high fT4 levels. In those with low or high fT4, the levels deviated only slightly from the reference range; therefore all 615 participants were considered euthyroid. Twenty-six participants had a high thyrotropin level: 23 of these had a sub-clinical and three a clinical hypothyroidism according to biochemical criteria. Twenty-four participants had a low thyrotropin level: all of these had a sub-clinical and none had clinical hyperthyroidism according to biochemical criteria. Plasma levels of thyrotropin were inversely correlated with both T4 (r = −0.20, p < 0.01) and fT4 (r = −0.22, p < 0.01).

No differences were observed in thyroid hormone levels between the prevalent dementia cases and the non-demented participants at exam 4 (data not shown). Characteristics of the remaining 665 participants at risk for dementia are presented in table 1, stratified according to tertiles of fT4. Higher age, higher serum total and lower HDL cholesterol, were all related to a lower fT4. No significant associations were found with the other characteristics, including APOE genotype.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study sample at risk for dementia (n=665) stratified according to tertiles of free thyroxine, The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study

| Characteristics | Sample at risk for dementia Stratified by tertiles of free thyroxine* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P for trend | |

| Age at baseline, y | 78.6 (5.2) | 78.4 (7.2) | 77.3 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Education, y | 10.3 (3.2) | 10.2 (3.2) | 10.4 (3.1) | 0.63 |

| Late-life total cholesterol, mg/dL | 188.1 (33.7) | 183.6 (34.8) | 191.6 (30.5) | 0.008 |

| Late-life HDL-C, mg/dL | 48.5 (12.4) | 49.8 (12.8) | 53.0 (13.3) | <0.0001 |

| Late-life body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.5 (3.2) | 23.3 (3.2) | 23.4 (3.2) | 0.65 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 32 | 36 | 37 | 0.29 |

| Late-life smoking (current), % | 43 | 36 | 37 | 0.16 |

| Late-life diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80.1 (11.6) | 78.6 (11.3) | 79.8 (10.8) | 0.19 |

| Late-life systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 147.6 (25.1) | 146.6 (22.9) | 146.6 (23.1) | 0.80 |

| Late-life beta-blocker use, % | 8 | 7 | 10 | 0.16 |

| ApoE ε4, % carrier | 18 | 18 | 22 | 0.27 |

Values are age-adjused means (standard deviation) or percentages

3.2 Thyroid hormones and incident dementia

Thyrotropin was not associated with the risk of dementia or AD. However, with each standard deviation increase in fT4, the risk of dementia increased over 20% and the risk of AD increased over 30% [table 3]. Per standard deviation increase in T4, the risk of dementia increased 19% and the risk of AD increased 22%; however this was not statistically significant. Results did not markedly change after additional adjustment for potential confounders, stratification by Apo E ε4 status or exclusion of participants with hyper- or hypothyroidism or on thyroid medication.

In addition, the risk of dementia did not differ between participants with normal thyrotropin levels and those with a high or low thyrotropin level, but these analyses were limited by low numbers: three of the 26 participants with a high thyrotropin level at baseline developed dementia, whereas six of the 24 participants with a low thyrotropin level developed dementia.

3.3 Thyroid hormones and neuropathology

Thyrotropin and fT4 were not associated with neuropathologic markers of AD. For instance, per SD increase in thyrotropin the neocortical NFT count was 0.01 (95% CI – 0.04; 0.07) lower and the neocortical NP count was 0.01 (95% CI –0.05; 0.06) lower. Per SD increase in fT4 the neocortical NFT count was 0.15 (95% CI –0.04; 0.34) higher and the neocortical NP count was 0.01 (95% CI –0.28; 0.29) higher. There were no significant associations between thyroid function and NFT and NP count in the hippocampus.

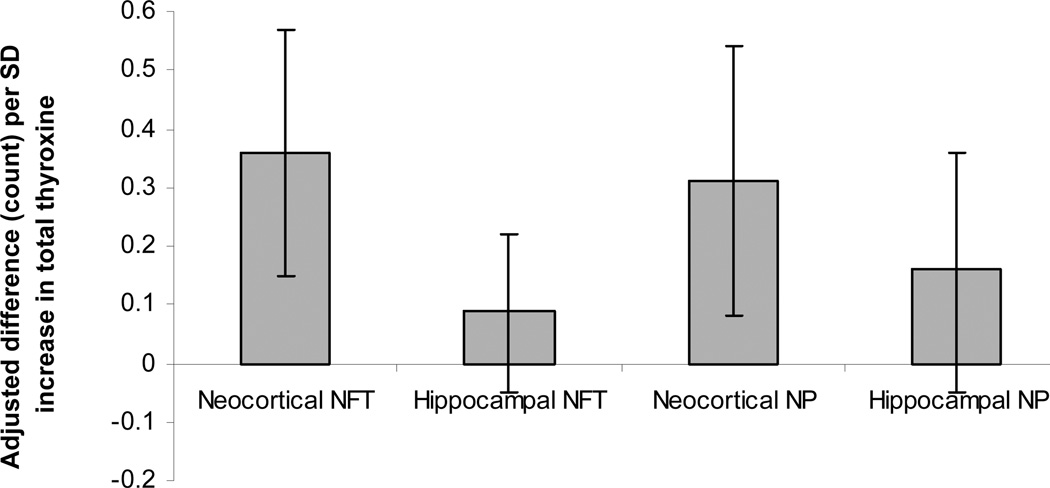

Higher levels of T4 were associated with more neocortical NFT and NP. Per SD increase in T4, the neocortical NFT count was 0.25 (95% CI, 0.05;0.46) higher and the neocortical NP count was 0.22 (95% CI, −0.01;0.44) higher, although the latter was non-significant. T4 was not associated with hippocampal NFT and NP. These results were slightly strengthened after adjusting for potential confounders (Figure 1). Stratifying by presence or absence of dementia did not change the results.

Figure 1.

Values represent adjusted differences (95% confidence intervals) in autopsy measures per SD increase in total thyroxine. NFT: neurofibrillary tangles, NP: neuritic plaques, CI: Confidence Interval

Values are adjusted for age, albumin, educational level, depressive symptom score, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, anti-arrhythmic and beta-blocking agent use.

4. Discussion

In this population-based study of very old men, higher levels of fT4 and T4 were associated with an increased risk for both dementia and AD. T4 was also associated with more neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex, whereas fT4 was not. Adjustment for potential confounding factors did not change the results.

Strengths of this study are its prospective population-based design, the six years of follow-up and the extensive diagnostic work-up for dementia including neuroimaging in most cases. In addition to the diagnosis of a clinical dementia syndrome, neuropathologic markers of AD were available in an autopsy series of the cohort. It should be noted, thyroid hormones were assayed in only one third of all study participants. However, we randomly selected participants for the assessments of thyroid hormones, and did not find any differences between the subgroups with and without thyroid hormone assessments. Further, the number of participants with (sub-clinical) hypo- and hyperthyroidism was quite small, thus limiting our analyses on participants with abnormal thyroid function.

Whereas in the Rotterdam Study an association between sub-clinical hyperthyroidism and dementia was found [16], in this study thyrotropin was not related to clinically diagnosed AD or Alzheimer-type neuropathology. This was the case when analyzed continuously or when analyzed in strata of normal or abnormal thyroid function, although the analyses on high and low thyrotropin were limited due to low numbers. Thyrotropin values may however be altered by as much as 30% depending on time of day of phlebotomy, and the fasting or non-fasting status of the participant [26]. The absence of an effect of thyrotropin in our study could thus in part be due to differences in time of blood collection or in certain characteristics of the population studied. Moreover, a blunted response of thyrotropin to thyrotropin-releasing hormone has been reported in elderly with major depression or AD [22], indicating that in these conditions thyrotropin does not always adequately reflect thyroid function [19]. Whereas thyrotropin was not associated with AD in our study, both T4 and fT4 were associated with an increased risk. This is in line with findings from the Rotterdam Study but contrasts findings from the Rotterdam Scan Study where thyroid function was not related to dementia-risk.

Our findings are in line with several reports from experimental studies showing thyroid hormones to induce changes in amyloid precursor processing or deposition of amyloid-β [4, 17]. Moreover, we also found an association of T4 with neuropathological markers of AD in the non-demented subjects. The higher count of neocortical NFT and NP in participants with higher T4 is consistent with our findings of an association between T4 and AD. In addition, in the Rotterdam Scan Study in subjects who were not demented, higher thyroid hormone levels were associated with a smaller hippocampal and amygdalar volumes on MRI, both of which are putative MRI markers of Alzheimer disease. Taken together, these findings suggest that higher thyroid function within the normal range could be involved in the pathophysiology of dementia and AD.

Alternative explanations should be discussed. Although the mean follow-up duration for dementia in our study population was nearly 5 years, the insidious onset and slowly progressive nature of AD may also indicate that higher thyroid function is a marker of sub-clinical disease rather than causal factor in the development of AD. Sub-clinical dementia might lead to higher thyroid hormone levels through several mechanisms. First, higher T4 levels may be due to neurodegeneration The hippocampus, a structure in the medial temporal lobe of the brain, is involved early in Alzheimer pathogenesis and has been shown to be reduced in volume on brain imaging up to six years before clinical detection of AD [11]. The hippocampus is involved in the setting of the basal activity of the thyroid axis through hippocampal-hypothalamic connections. By decreasing thyroid-hormone-releasing hormone gene expression in the hypothalamus, the hippocampus exerts a negative effect on this axis [27]. If the affected hippocampus in AD leads to less feedback on the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis, higher levels of fT4 could follow. The finding that higher serum fT4 levels are associated with smaller hippocampal volumes on MRI scans of non-demented elderly [10], may offer support for this hypothesis.

Second, higher T4 levels may result from dementia through concomitant nonthyroidal illness. Evaluation of thyroid function in the elderly is complicated by an increased prevalence of non-thyroidal illness [7], in which thyroid hormone and thyrotropin concentrations are altered, without overt thyroid dysfunction being present. Several conditions including malnutrition, starvation, and inflammatory processes accompanying disease are associated with non-thyroidal illness. In these situations, T4 is converted preferentially to reverse T3 instead of T3 [8]. The finding that not only fT4 but also higher levels of reverse T3 were found to be associated with smaller hippocampal volume on MRI of non-demented elderly [10] indeed suggests that this may be an important mechanism. Since both T3 and reverse T3 were not measured in our study, we were not able to adjust for nonthyroidal illness. The fact that results remained unaltered after adjusting for potential other confounders, argues at least in part against an effect of comorbidity, although residual confounding by other measures influencing both thyroid hormone levels and our outcome measures cannot be excluded.

To conclude, in our study of elderly Japanese-American men, higher thyroid function as indicated by increased levels of fT4 and T4 levels within the normal range was associated with an increased risk of dementia and AD. In addition, higher levels of total T4 were associated with Alzheimer-type neuropathology. Taken together, our findings suggest that higher fT4 and T4 levels may reflect early AD. Yet, future studies are needed to determine whether higher thyroid hormone levels are a causal factor in the development of AD, or whether they reflect sub-clinical disease.

Table 2.

Thyroid hormone levels and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease, the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study.

| Thyroid hormones | Dementia (n=106) |

Alzheimer disease (n=74) |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | |

| Model 1b | ||

| Thyrotropin (per SD) | 0.93 (0.82 ; 1.06) | 0.92 (0.78 ; 1.09) |

| fT4 (per SD) | 1.21 (1.04 ; 1.40) | 1.31 (1.14 ; 1.51) |

| T4 (per SD) | 1.19 (0.99 ; 1.43) | 1.22 (0.98 ; 1.52) |

| Model 2c | ||

| Thyrotropin (per SD) | 0.89 (0.74; 1.07) | 0.90 (0.71 ; 1.13) |

| fT4 (per SD) | 1.20 (1.05 ; 1.37) | 1.30 (1.14 ; 1.47) |

| T4 (per SD) | 1.10 (0.87 ; 1.39) | 1.14 (0.86 ; 1.52) |

Values are hazard ratios for dementia and Alzheimer disease per SD increase in thyroid hormone level (95% confidence interval)

Model 1: age adjusted

Model 2: also adjusted for albumin, educational level, depressive symptom score, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, anti-arrhythmic and beta-blocking agent use.

Acknowledgements

The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging (contract # N01-AG-4-2149, grant # UO1-AG-0-9349-03 and RO1-AG-0-7155-06A1), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (contract # N01 –HC-0-5102), and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, This research was also made possible in part by grants from the International Foundation of Alzheimer Research (ISAO grant 01500) and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW, grant 904-61-155).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: all authors reported no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Frank Jan de Jong, Email: f.j.dejong@erasmusmc.nl.

Kamal Masaki, Email: khmasaki@phrihawaii.org.

Hepei Chen, Email: chenhep@mail.nih.gov.

Alan T. Remaley, Email: ARemaley@cc.nih.gov.

Monique M.B. Breteler, Email: m.breteler@erasmusmc.nl.

Helen Petrovitch, Email: hpetrovitch@phrihawaii.org.

Lon R. White, Email: lrwhite@prhihawaii.org.

Lenore J. Launer, Email: launerl@nia.nih.gov.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders, Revised third Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT Software, version 8.0 for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.SPSS Inc. Advanced Statistical Analysis Using SPSS, version 10.0 for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belandia B, Latasa MJ, Villa A, Pascual A. Thyroid hormone negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30366–30371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boelaert K, Franklyn JA. Thyroid hormone in health and disease. J. Endocrinol. 2005;187:1–15. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breteler MM, van Duijn CM, Chandra V, Fratiglioni L, Graves AB, Heyman A, Jorm AF, Kokmen E, Kondo K, Mortimer JA. Medical history and the risk of Alzheimer's disease: a collaborative re-analysis of case-control studies. EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1991;20 Suppl 2:S36–S42. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.supplement_2.s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiovato L, Mariotti S, Pinchera A. Thyroid diseases in the elderly. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;11:251–270. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(97)80272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra IJ, Hershman JM, Pardridge WM, Nicoloff JT. Thyroid function in nonthyroidal illnesses. Ann. Intern. Med. 1983;98:946–957. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-6-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chui HC, Victoroff JI, Margolin D, Jagust W, Shankle R, Katzman R. Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the State of California Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers. Neurology. 1992;42:473–480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong FJ, den Heijer T, Visser TJ, de Rijke YB, Drexhage HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Thyroid hormones, dementia and atrophy of the medial temporal lobe. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:2569–2573. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Heijer T, Geerlings MI, Hoebeek FE, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Use of hippocampal and amygdalar volumes on magnetic resonance imaging to predict dementia in cognitively intact elderly people. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:57–62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugbartey AT. Neurocognitive aspects of hypothyroidism. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:1413–1418. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganguli M, Burmeister LA, Seaberg EC, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Association between dementia and elevated TSH: a community-based study. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;40:714–725. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havlik RJ, Izmirlian G, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki K, Curb JD, Saunders AM, Foley DJ, Brock D, Launer LJ, White L. APOE-epsilon4 predicts incident AD in Japanese-American men: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study. Neurology. 2000;54:1526–1529. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J. Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalmijn S, Mehta KM, Pols HA, Hofman A, Drexhage HA, Breteler MM. Subclinical hyperthyroidism and the risk of dementia. The Rotterdam study. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 2000;53:733–737. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latasa MJ, Belandia B, Pascual A. Thyroid hormones regulate beta-amyloid gene splicing and protein secretion in neuroblastoma cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2692–2698. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Launer LJ. Demonstrating the case that AD is a vascular disease: epidemiologic evidence. Ageing Res. Rev. 2002;1:61–77. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariotti S, Franceschi C, Cossarizza A, Pinchera A. The aging thyroid. Endocr. Rev. 1995;16:686–715. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-6-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molchan SE, Lawlor BA, Hill JL, Mellow AM, Davis CL, Martinez R, Sunderland T. The TRH stimulation test in Alzheimer's disease and major depression: relationship to clinical and CSF measures. Biol. Psychiatry. 1991;30:567–576. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90026-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrovitch H, Nelson J, Snowdon D, Davis DG, Ross GW, Li CY, White L. Microscope field size and the neuropathologic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1997;49:1175–1176. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovitch H, White LR, Ross GW, Steinhorn SC, Li CY, Masaki KH, Davis DG, Nelson J, Hardman J, Curb JD, Blanchette PL, Launer LJ, Yano K, Markesbery WR. Accuracy of clinical criteria for AD in the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, a population-based study. Neurology. 2001;57:226–234. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross DS. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement for assessment of thyroid function and disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001;Vol. 30:245–264. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70186-9. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scobbo RR, VonDohlen TW, Hassan M, Islam S. Serum TSH variability in normal individuals: the influence of time of sample collection. W. V. Med. J. 2004;100:138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi ZX, Levy A, Lightman SL. Hippocampal input to the hypothalamus inhibits thyrotrophin and thyrotrophin-releasing hormone gene expression. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:576–580. doi: 10.1159/000126409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Small GW, Matsuyama SS, Komanduri R, Kumar V, Jarvik LF. Thyroid disease in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1985;33:538–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb04617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, Sawin CT, Col NF, Cobin RH, Franklyn JA, Hershman JM, Burman KD, Denke MA, Gorman C, Cooper RS, Weissman NJ. Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management. Jama. 2004;291:228–238. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syme SL, Marmot MG, Kagan A, Kato H, Rhoads G. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: introduction. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1975;102:477–480. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, Imai Y, Larson E, Graves A, Sugimoto K, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki H, Chiu D. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Osch LA, Hogervorst E, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Low thyroid-stimulating hormone as an independent risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:1967–1971. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000128134.84230.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki KH, Abbott RD, Teng EL, Rodriguez BL, Blanchette PL, Havlik RJ, Wergowske G, Chiu D, Foley DJ, Murdaugh C, Curb JD. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Jama. 1996;276:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshimasu F, Kokmen E, Hay ID, Beard CM, Offord KP, Kurland LT. The association between Alzheimer's disease and thyroid disease in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology. 1991;41:1745–1747. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.11.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]