Abstract

The objective was to assess the impact of genetic variation on cervical cytokine concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and first, to determine if these variants interact with polymorphisms in toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) that were previously shown to associate with pro-inflammatory cervical cytokine concentrations, and second, to determine if findings are affected by bacterial vaginosis (BV). We examined 183 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 13 cytokine genes and receptors for associations with cervical cytokine levels in 188 African American and European American women. We tested for associations of genegene interactions between SNPs in TLR4 and cytokine gene and receptor polymorphisms with cervical pro-inflammatory cytokines. None of the single locus associations was significant after correction for multiple testing in either European Americans or African Americans. However, there were significant gene-gene interactions between IL-1R2 rs485127 and two SNPs in TLR4 (rs1554973 and rs7856729) with IL-1β after correction for multiple testing. Our study demonstrates that interactions between TLR4 and IL-1R2 are associated with cervical pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations. These results provide important insights into the possible regulatory mechanisms of the inflammatory response in the presence and absence of microbial disorders such as BV. Additionally, the observed differences in allele frequencies between African Americans and those of European descent may partially explain population disparity in pregnancy-related phenotypes that are cytokine concentration-dependent.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, cytokine concentrations, ethnic disparity

Introduction

The vaginal milieu comprises many types of micro-organisms; some, such as lactobacilli, promote a healthy micro-environment, while others, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, and Mobiluncus spp., can be harmful. Local innate immunity plays a critical role in regulating both the response and susceptibility to these micro-organisms (Fidel 2003; Russell et al. 2004). Vaginal disorders such as bacterial vaginosis (BV) arise when the local immune system fails to prevent harmful anaerobic bacteria from propagating. BV can cause serious adverse reproductive outcomes, especially during pregnancy, such as amniotic fluid infection, spontaneous preterm delivery (sPTD), and premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) (Kurki et al. 1992; Silver et al. 1989).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are important mediators of the inflammatory response and critical factors in cell-mediated immunity that constitute the main defenses against invading pathogens. Vaginal interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β and IL-8 concentrations are usually increased in women with BV; however, this trend is not always observed (Basso et al. 2005; Cauci et al. 2003; Hedges et al. 2006; Imseis et al. 1997; Mattsby-Baltzer et al. 1998; Platz-Christensen et al. 1993; Ryckman et al. 2008b; Wasiela et al. 2005). Several genetic polymorphisms, particularly those in IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, are associated with BV (Cauci et al. 2007; Genc et al. 2004; Goepfert et al. 2005). However, few studies have examined the connection between these genetic polymorphisms and cervical cytokine concentrations.

Additionally, African Americans are at a greater risk of BV as well as several pregnancy-related disorders, including preterm birth, than European Americans, a result not entirely explained by environmental factors alone (Kramer et al. 2001; Ness et al. 2003). Recent reports indicated that not only do cytokine correlation patterns differ between African Americans and European American pregnant women, but European American women have higher cervical concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-6 than their African-American counterparts (Ryckman et al. 2008a; Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2008b; Williams et al. 2010). Genetic associations between SNPs in toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and cervical pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, have been identified in European Americans but not African Americans (Ryckman et al. 2009). IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) and TLR4 share downstream signaling molecules, and both are important factors in the expression and regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Akira et al. 2001). Therefore, it is possible that TLR4 and IL-1R could interact to influence pro-inflammatory cervical cytokine concentrations, and this interaction could occur differently in European Americans compared with African Americans.

In this investigation, we explore the pro-inflammatory aspect of cervical immunity represented by cervical concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Given that many cytokine gene and receptor polymorphisms differ in allele frequency across populations and that the prevalence of BV is higher in African-Americans compared with European Americans, we created global models to determine if pro-inflammatory cytokine genes interact with SNPs in TLR4, a gene that has previously been associated with an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines in European American but not African American populations. Interactions between pro-inflammatory cytokine genes and TLR4 could provide a global model for the differential expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines observed between African-Americans and European Americans, which could ultimately help explain the higher prevalence of reproductive and vaginal disorders such as BV in African Americans.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

A prospective, observational cohort study of women from the general obstetrical population seeking prenatal care was performed at the Magee-Women’s Hospital prenatal clinic. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh and Vanderbilt University. Inclusion criteria for the cohort study were singleton intrauterine gestation prior to 13 weeks’ gestation and a self-reported race of either black or white. Exclusion criteria included vaginal bleeding, fetal anomalies, known thrombophilias, pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension requiring medication, current or planned cervical cerclage, immune compromise (HIV-positive, use of systemic steroids within six months, use of post-transplant immunosuppressive medication) and autoimmune disease (inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma). These exclusions were developed prior to study enrollment because they are believed to be associated with preterm delivery or an alteration in the immune status, which would confound the associations we proposed to examine. All women provided demographic, medical and clinical information through standardized, closed-question research interviews administered by research personnel. Two vaginal swabs were collected for culture and identification of vaginal flora. BV was diagnosed by vaginal pH ≥ 4.7 and a score of 7 through 10 from a Gram-stained vaginal smear interpreted using the Nugent method (Nugent et al., 1991). Additional details on this cohort as well as cytokine measurement and detection are described in detail elsewhere (Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2008b), but briefly, in addition to vaginal swabs, cervical swabs were obtained for the measurement of cytokine concentrations.

Ninety-three African Americans and ninety eight European Americans were evaluated in this study after excluding women who were positive for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, or T. vaginalis, who were not self identified as European Americans or African Americans, who had an intermediate BV score, had no Gram stain score, were under 18 or had no cytokine measurements. Socio-demographic characteristics by racial distribution have been described in detail previously (Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2008b).

DNA Collection and Genotyping

One hundred and eighty-three tagSNPs from 13 genes were examined for association with cervical cytokine concentrations. Pro-inflammatory interleukins and tumor necrosis factor were selected from a panel of 133 candidate genes that were genotyped for the study of preterm birth. The genes chosen included: IL-1α (3 SNPs), IL-1β (7 SNPs), interleukin 1 receptor 1 (IL-1R1: 16 SNPs), interleukin receptor 2 (IL-1R2: 21 SNPs), interleukin receptor antagonist (IL-1RN: 14 SNPs), interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAP: 60 SNPs), IL-6 (7 SNPs), interleukin 6 receptor (IL-6R: 20 SNPs), IL-8 (2 SNPs), interleukin 8 receptor alpha (IL-8RA: 3 SNPs), TNF-α (3 SNPs), tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1: 9 SNPs) and tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2: 18 SNPs) (Supplemental Table 1). TagSNPs were selected based on their ability to tag surrounding variants in the Caucasian (CEPH) and Yoruban (YRI) populations of the HapMap database (http://www.hapmap.org). Minor allele frequencies of 0.07 in CEPH and 0.20 in YRI and an r2 of 0.80 were used to determine tagSNPs. Genotyping was performed on the Illumina GoldenGate platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). There was an average SNP genotyping efficiency of 99.7%, with no SNP having genotyping efficiency less than 82%, and no individual selected for analysis had a genotyping efficiency of less than 97%. The software program PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/) was utilized to compare allelic and genotypic distributions between ethnic groups with Fisher’s exact tests and to test for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in each race separately, also with Fisher’s exact tests. To assess the accuracy of self-reported ancestry, structure analysis was performed on 1337 markers that cover 22 chromosomes with Structure 2.2 (Pritchard et al. 2000). This analysis indicated two distinct clusters in almost complete agreement with the self-reported ancestry with the exception of one self-reported European American who clustered with self-reported African Americans and two self-reported African Americans who clustered with self-reported European Americans. Therefore, these individuals were removed from subsequent analysis, leaving 97 European Americans and 91 African Americans for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The relationship between each cytokine and polymorphism in the cytokine gene or receptor were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric tests, depending on the normality of the distribution for any given cytokine. None of the cytokines examined was normally distributed. After transforming with either natural log or box cox, it was determined that the box cox transformation was better for IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Shapiro–Wilks p > 0.01 in both European Americans and African Americans). ANOVA analyses were performed for these cytokines stratified by race and included the interaction between BV status and SNP. The full model was: transformed cytokine concentration = μ + α(SNP) + β(BV status) + γ(BV status*SNP) + ε. Bartlett’s test for equal variances was performed for all interaction terms and reported for SNPs associated with cytokine concentration, if significant. Additive, dominant and recessive models were analyzed for all cytokine concentrations; however, models were not tested if there were fewer than five individuals for any genotype in the model.

For those cytokines not normally distributed after transformation (IL-8 and TNF-α), Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to determine if cytokine concentration differed by genotype and BV status. Therefore, for additive models there were six strata (BV+ with three genotypic classes (AA vs AB vs BB) and BV− with three genotypic classes) and for dominant and recessive models there were four strata (BV+ with two genotypic classes [AA/AB vs BB for dominant models and AA vs AB/BB for recessive models] and BV− with two genotypic classes). Again, to limit the number of tests performed, genetic models were only examined if there were five or more individuals per genotypic class. A total of 2431 (1208 tests in African Americans and 1148 tests in European Americans) tests were performed. This number included tests for all evaluated genetic models, cytokine concentrations, both races and interaction and single SNP main effects. Results were adjusted for this number of tests with the False Discovery Rate (q=0.2) (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). SNP and interaction effects were analyzed further with the Sidak test, or the rank sum test for cytokines not normally distributed after transformation. These tests determined which group (BV+ or BV−) was driving the significance. The Sidak test calculates p values that are corrected for multiple testing. Calculations were performed using Stata version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

In order to explore interactions between pro-inflammatory genes and SNPs in toll-like receptor 4, previously shown to be associated with pro-inflammatory cervical cytokine measurements, a more lenient threshold of p<0.01 was used for inclusion in the analysis. Four SNPs associated with either IL-1α (IL-1RAP rs6444435) or IL-1β (IL-1R2 – rs4851527 and rs4851531, IL-1RAP – rs6765375) in AA were tested for interaction effects with two SNPs in TLR4 (rs1554973 and rs7856729) that associated with IL-1α and IL-1β in European Americans in a previous study (Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2009). Interactions were tested, using ANOVAs that included individual SNP main effects, race, BV status and the interaction term between the two SNPs. In order to maximize power only dominant and recessive models were tested for interaction effects. Therefore, each SNP by SNP interaction was evaluated under four possible models: SNP1 dominant by SNP2 dominant, SNP1 dominant by SNP2 recessive, SNP1 recessive by SNP2 dominant and SNP1 recessive by SNP2 recessive. ANOVAs were also performed stratified by race. A total of 64 ANOVAs were performed and corrected for multiple testing with FDR. Those found to be significant were analyzed further with linear regression to determine the r2 and a likelihood ratio test was performed to determine whether removing the interaction term had a considerable impact on the model’s significance.

Results

One-hundred and eighty-three SNPs encompassing 13 cytokine genes and receptors were examined; of these, there were 123 significant allele or genotype differences between ethnic groups (Supplemental Table 1). Eight SNPs deviated from HWE in African Americans and European Americans, 10 deviated in African Americans only and 14 deviated in European Americans only.

In African Americans 33 SNPs from IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1R1, IL-R2, IL-1RAP, IL-6, IL-6R, IL-8RA, and TNFR2 had marginally significant SNP or BV by SNP interactions associated with IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 or TNF-α concentrations (Supplemental Table 2a). None of these associations remained significant after correction for multiple testing with FDR. The most significant SNP associations (p < 0.01) included 2 SNPs in IL-1RAP; one (rs6444435) associated with IL-1α (p = 0.004) and the other (rs6765375) associated with IL-1β concentrations (p = 0.005; Table 1). Two SNPs in IL-1R2 (rs4851527 and rs4851531) associated with IL-1β concentrations (p = 0.007 and 0.006, respectively; Table 1). In addition an SNP in IL1RAP (rs7650510) and an SNP in IL-6R (rs44595618) had significant SNP by BV status interactions with IL-1α (p = 0.008) and IL-6 (p = 0.005), respectively.

Table 1.

Significant interactions between SNP and BV status in AA

| Mean ± Standard Deviation of Transformed Cytokines, n is number of obs. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | SNP | Intxn | BV−and BV+ | BV− | BV+ | ||||||

| Cyto | Gene | RS# | (Geno1 vs 2) | p | p | Geno 1 | Geno 2 | Geno 1 | Geno 2 | Geno 1 | Geno 2 |

| IL-1α | IL-1RAP | rs6444435 | AA vs AG/GG |

0.004 | 0.670 | 4.0±0.3 n=32 |

3.8±0.3 n=57 |

3.8±0.3 n=13 |

a3.6±0.2 n=25 |

4.1±0.3 n=19 |

3.9±0.3 n=32 |

| IL-1α | IL-1RAP | rs7650510 | AA vs AG/GG |

0.628 | 0.008 | 3.8±0.3 n=46 |

3.9±0.3 n=43 |

3.8±0.3 n=21 |

a3.6±0.2 n=17 |

3.9±0.3 n=25 |

4.0±0.3 n=26 |

| IL-1β | IL-1R2 | rs4851527 | AA vs AG/GG |

0.007 | 0.996 | 2.4±2.0 n=6 |

5.6 ±2.3 n=81 |

1.68 n=1 |

5.2±2.3 n=37 |

b2.5±2.2 n=5 |

6.0±2.2 n=44 |

| IL-1β | IL-1R2 | rs4851531 | CC vs CT/TT | 0.006 | 0.778 | 4.2±3.0 n=22 |

5.8±2.0 n=65 |

3.8±3.3 n=10 |

5.6±1.8 n=28 |

4.6±2.8 n=12 |

6.0±2.2 n=37 |

| IL-1β | IL-1RAP | rs6765375 | AA vs AC/CC | 0.005 | 0.048 | 4.0±2.8 n=9 |

5.6±2.3 n=78 |

c0.6±1.5 n=2 |

5.3±2.2 n=36 |

4.9±2.4 n=7 |

5.8±2.4 n=42 |

| IL-6 | IL-6R | rs11265618 | CC/CT vs TT | 0.773 | 0.005 | 25.4±6.9 n=81 |

24.4±11.3 n=5 |

25.1±7.7 n=33 |

a16.8±6.0 n=3 |

25.5±6.4 n=48 |

35.8±2.2 n=2 |

BV+ vs BV− for genotype 2: rs6444435 p = 0.001, rs7650510 p < 0.001, rs11265618 p = 0.021

Genotype 1 vs Genotype 2 for BV+ group: rs4851527 p = 0.009

Genotype 1 vs Genotype 2 for BV− group: rs6765375 p = 0.035

In European Americans 26 SNPs from IL-1α, IL-1R1, IL-R2, IL-1RAP, IL-1RN, IL-6, IL-6R, and TNFR2 had significant SNP or BV by SNP interactions associated with IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 or TNF-α concentrations (Supplemental Table 2b). None of these associations remained significant after correction for multiple testing with FDR, nor were any of these significant at p < 0.01.

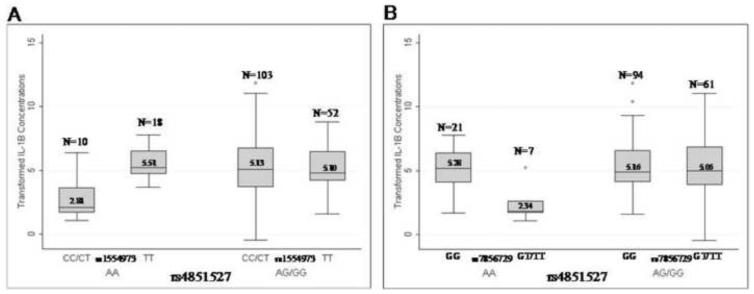

The four SNPs that had significant single SNP associations with either IL-1α (IL-1RAP rs6444435) or IL-1β (IL-1R2 – rs4851527 and rs4851531, IL-1RAP – rs6765375) in AA were tested for interaction effects with the two SNPs in TLR4 (rs1554973 and rs7856729) that were associated with IL-1α and IL-1β in European Americans in a previous study (Platz-Christensen et al. 1993[pd1]). European American and African American samples were analyzed together to determine if a TLR4 by IL-1R2 or IL-1RAP interaction explained the individual associations of TLR4 in European Americans and IL-1R2 and IL-1RAP in African Americans. Several of the genegene interactions were significant; the interactions between IL-1R2 rs485127 and either SNP in TLR4 (rs1554973 or rs7856729) were significantly associated with IL-1β after correction for multiple testing with FDR (p = 2.2×10−4 for rs485127 x rs1554973 and 2.3×10−4 for rs485127 x rs1554973) (Supplemental Table 3). All of the terms (race, BV status, SNP main effects and SNP by SNP interaction) were significant in these models. Women with the AA genotype at rs4851527 and the CC/CT genotypes at rs1554973 or the GT/TT genotypes at rs7856729 had lower cervical IL-1β levels compared with women with the TT genotype at rs1554973 or the GG genotype at rs7856729 (Figure 1). Additionally, women with the CC/CT genotypes at rs1554973 or the GT/TT genotypes at rs7856729 and the AA genotype at rs4851527 had lower cervical IL-1β concentrations than those with the AG/GG genotype at rs4851527 (Figure 1). The model with the interaction between TLR4 rs1554973 and IL-1R2 rs4851527 had an r2 of 0.1816, while the model without the interaction had an r2 of 0.1157 (likelihood ratio test p = 2×10−4). Results were similar for the interaction between TLR4 rs7856729 and IL1R2 rs4851527, where the r2 with the interaction was 0.1615 compared with an r2 of 0.0943 for the model without the interaction (likelihood ratio test p = 2×10−4).

Figure 1.

Concentrations of box cox transformed IL-1β by TLR4 rs4851527 and either a) rs1554973 or b) rs7856729

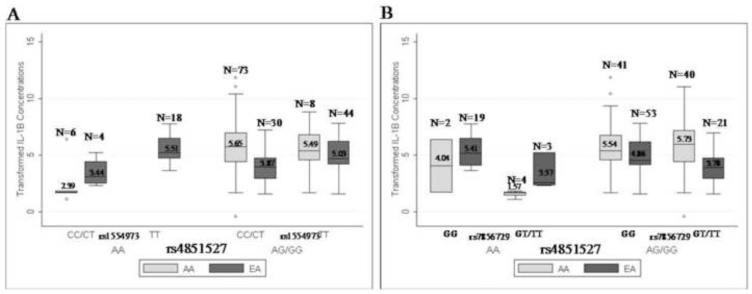

The associations with TLR4 rs1554973 or rs7856729 and IL-1R2 rs4851527 were no longer significant when stratified by race (Supplemental Table 3). This may be due to African American women with the AA genotype at rs485127 having lower concentrations of IL-1β than European American and African American women with the AG/GG genotypes having higher IL-1β concentrations than European American women (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of box cox transformed IL-1β stratified by race for TLR4 rs4851527 and either a) rs1554973 or b) rs7856729

Discussion

It remains unclear as to why some women with BV experience adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm delivery while others do not. Several studies have observed higher serum, amniotic fluid or vaginal concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in women with BV or in those experiencing preterm delivery (El-Bastawissi et al. 2000; Menon et al. 2007, 2008a; Romero et al. 1990; Ryckman, Williams, & Kalinka 2008a; Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2008b; Velez et al. 2007). Several studies have also observed that genetic polymorphisms in pro-inflammatory genes are associated with BV and preterm delivery; however, few of these studies have assessed the impact of genetic variation in pro-inflammatory genes or their receptors on vaginal or cervical cytokine levels (Engel et al. 2005; Macones et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2006). Because of it potential clinical importance and our lack of understanding of the regulation of cervical cytokines, we chose to examine how genes and infection may interact to have an impact on these concentrations. Therefore, we examined genetic polymorphisms in IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α and their receptors for association with cervical cytokine concentrations, and determined whether BV status interacted with these polymorphisms to affect cytokine levels. Additionally, we determined whether statistical interactions exist between SNPs in TLR4 and those in pro-inflammatory cytokine genes or receptors with cervical pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations.

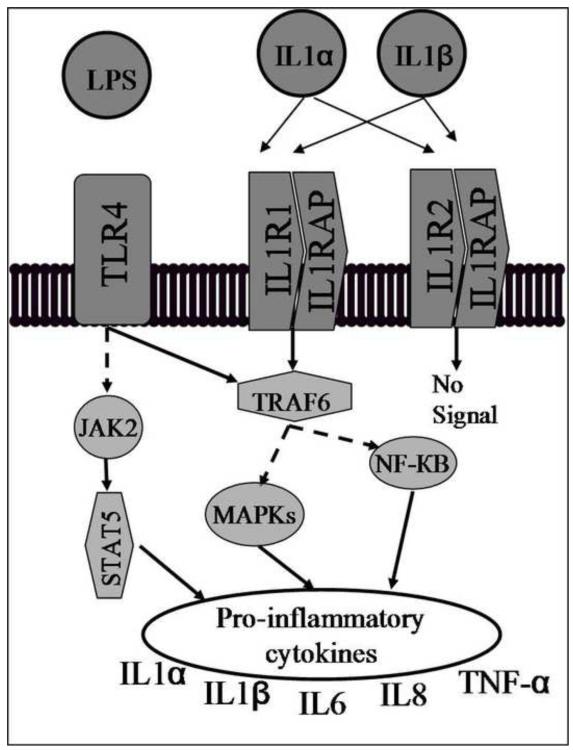

Our study identified several SNPs in IL-1RAP and IL-1R2 that were associated with IL-1α or IL-1 β concentrations in African Americans. Only one of these SNPs (IL-1RAP rs6444435) was also associated with cervical cytokine concentrations in European Americans (p = 0.02). IL-1RAP binds to either IL-1R1 or IL-1R2. When bound to IL-1R1, signal transduction occurs, whereas the IL-1R2/IL-1RAP complex does not result in signal transduction. IL-1R2 competes for the binding of the IL-1α or IL-1 β proteins, thereby limiting the amount of either molecule that can activate the signal transduction cascade (Figure 3). Even though none of these associations remained significant after correction for multiple testing, an important trend is observed in that the majority of the associations (~80%) in either African Americans or European Americans are with SNPs in gene receptors or cofactors and not the genes themselves. This is supported by other studies that have also found associations in cytokine gene receptors, such as TNFR1, TNFR2, and IL-6R with TNF-α and IL-6 amniotic fluid concentrations (Menon et al. 2008c; Velez et al. 2008).

Figure 3.

Cross-talk between TLR4 and IL-1 signaling pathways. Activation of TLR4 by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) initiates a signal through the Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (JAK-STAT1) pathway as well as through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6). IL-1 signal transduction is initiated through the TRAF6 signaling pathway by the binding of either IL-1α or IL-1β to the IL-1R1/IL-1RAP complex. The IL-1R2/IL-1RAP complex competes for the binding of IL-1α and IL-1β and does not produce a signal when bound, therefore limiting the availability of IL-1α or IL-1β to bind to the IL-1R1/IL-1RAP complex. A dashed line indicates that other signaling molecules not shown are also involved in the pathway.

It is known that African Americans and European Americans have different responses to infection as well as different allele frequencies for many SNPs in pro-inflammatory cytokine genes and receptors (Blake and Ridker 2003; Hoffmann et al. 2002; Menon et al. 2008b; Menon, Velez, Morgan, Lombardi, Fortunato, & Williams 2008c; Myslobodsky 2001; Ness 2004; Velez, Menon, Thorsen, Jiang, Simhan, Morgan, Fortunato, & Williams 2007; Velez, Fortunato, Williams, & Menon 2008). Our data support this as we observed varied allele frequencies in the majority of the pro-inflammatory SNPs evaluated. In particular, African Americans, compared with European Americans, had a lower minor allele frequency of the A allele for IL-1R2 rs4851527 (0.25 vs 0.47) and a higher allele frequency of the C allele for TLR4 rs1554973 (0.71 vs 0.21) and the T allele of rs7856729 (0.29 vs 0.15). The varied allele frequency between European Americans and African Americans may explain why the genegene interaction between IL-1R2 rs4851527 and TLR4 rs1554973 or rs7856729 was not as strong when testing the effect in African Americans and European Americans separately. We had greater power to detect the effect in African Americans and European Americans together, while still adjusting for race in the model. The model with the genegene effect that we identified explains about 18% of the variation in cytokine concentrations in pregnant women, and the interaction term produces a significantly better model. Further studies will need to be performed to replicate our result and larger populations are needed in order to obtain greater power to detect these effects.

While the associations we detected indicate a statistical not a biological genegene interaction, the observation has biological plausibility as the TLR4 and IL-1R signaling pathways are closely related, and lead to similar endpoints (Figure 3). It appears that these mechanisms are acting in parallel in African Americans and European Americans to influence cervical concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Because too much or too little cervical, serum or amniotic fluid cytokine are associated with reproductive complications such as chorioamnionitis, PTB, and BV it is important that appropriate responses are motivated (El-Bastawissi, Williams, Riley, Hitti, & Krieger 2000; Menon, Camargo, Thorsen, Lombardi, & Fortunato 2008a; Romero, Avila, Santhanam, & Sehgal 1990; Ryckman, Williams, & Kalinka 2008a; Ryckman, Williams, Krohn, & Simhan 2008b; Simhan et al. 2003; Velez, Menon, Thorsen, Jiang, Simhan, Morgan, Fortunato, & Williams 2007). Our data indicate that induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines may, to some extent, be mediated through different, but previously described, pathways in African American and European American women, but that both have a common touch point, TRAF6 (Figure 3) (Akira, Takeda, & Kaisho 2001). In essence, as is known, both TLR4 and IL1R can induce upregulation pro-inflammatory cytokines, and do so through different initiation steps. As such, this may provide a means of interaction such that initiation via TLR4 may be masked by upregulation via IL1RS if both signal through TRAF6 and vice versa. However, TLR4 may also signal through a different molecule (JAK2). Therefore, the end results may not be completely determined by one or the other of the two pathways and the effects of the two initiation steps may not be additive. Although this model is somewhat speculative, it is interesting in that, if true, it would lead to the conclusion that the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines is the product of convergent evolution. In other words, the end result may be driven by selection, but the path to the beneficial phenotype is different in the different geographic populations, perhaps motivated by differences in allele frequencies in the two populations, as well as by different selection patterns due perhaps to different past environments. Consistent with this argument is the observation that selection on TLRs differs among human populations (Barreiro et al. 2009). Therefore, our study provides a potentially important model for identifying women more likely to have higher or lower concentrations of IL-1α or IL-1β based on individual genotypes at both TLR4 and IL1-R2 and that these observations may have implications for understanding disparity in the risk of pregnancy outcomes. The functionality of this model will need to be tested in order to validate the proposed model.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat.Immunol. 2001;2(8):675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Ben-Ali M, Quach H, Laval G, Patin E, Pickrell JK, Bouchier C, Tichit M, Neyrolles O, Gicquel B, Kidd JR, Kidd KK, Alcais A, Ragimbeau J, Pellegrini S, Abel L, Casanova JL, Quintana-Murci L. Evolutionary dynamics of human Toll-like receptors and their different contributions to host defense. PLoS.Genet. 2009;5(7):e1000562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso B, Gimenez F, Lopez C. IL-1beta, IL-6 and IL-8 levels in gyneco-obstetric infections. Infect.Dis.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005;13(4):207–211. doi: 10.1080/10647440500240664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Blake GJ, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and other inflammatory risk markers in acute coronary syndromes. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2003;41(4 Suppl S):37S–42S. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauci S, Guaschino S, De AD, Driussi S, De SD, Penacchioni P, Quadrifoglio F. Interrelationships of interleukin-8 with interleukin-1beta and neutrophils in vaginal fluid of healthy and bacterial vaginosis positive women. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2003;9(1):53–58. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauci S, Di SM, Casabellata G, Ryckman K, Williams SM, Guaschino S. Association of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist polymorphisms with bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant Italian women. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2007;13(4):243–250. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bastawissi AY, Williams MA, Riley DE, Hitti J, Krieger JN. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6 and preterm delivery: a review. Obstet.Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 2):1056–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA, Erichsen HC, Savitz DA, Thorp J, Chanock SJ, Olshan AF. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth is associated with common proinflammatory cytokine polymorphisms. Epidemiology. 2005;16(4):469–477. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164539.09250.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidel PL. Immune Regulation and Its Role in the Pathogenesis of Candida Vaginitis. Curr.Infect.Dis.Rep. 2003;5(6):488–493. doi: 10.1007/s11908-003-0092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc MR, Onderdonk AB, Vardhana S, Delaney ML, Norwitz ER, Tuomala RE, Paraskevas LR, Witkin SS. Polymorphism in intron 2 of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene, local midtrimester cytokine response to vaginal flora, and subsequent preterm birth. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2004;191(4):1324–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goepfert AR, Varner M, Ward K, MacPherson C, Klebanoff M, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, Meis P, Iams J, Moawad A, Carey JC, Leveno K, Wapner R, Caritis SN, Miodovnik M, Sorokin Y, O’Sullivan MJ, Van Dorsten JP, Langer O. Differences in inflammatory cytokine and Toll-like receptor genes and bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005;193(4):1478–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SR, Barrientes F, Desmond RA, Schwebke JR. Local and systemic cytokine levels in relation to changes in vaginal flora. J.Infect.Dis. 2006;193(4):556–562. doi: 10.1086/499824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann SC, Stanley EM, Cox ED, DiMercurio BS, Koziol DE, Harlan DM, Kirk AD, Blair PJ. Ethnicity greatly influences cytokine gene polymorphism distribution. Am.J.Transplant. 2002;2(6):560–567. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imseis HM, Greig PC, Livengood CH, III, Shunior E, Durda P, Erikson M. Characterization of the inflammatory cytokines in the vagina during pregnancy and labor and with bacterial vaginosis. J.Soc.Gynecol.Investig. 1997;4(2):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Goulet L, Lydon J, Seguin L, McNamara H, Dassa C, Platt RW, Chen MF, Gauthier H, Genest J, Kahn S, Libman M, Rozen R, Masse A, Miner L, Asselin G, Benjamin A, Klein J, Koren G. Socio-economic disparities in preterm birth: causal pathways and mechanisms. Paediatr.Perinat.Epidemiol. 2001;15(Suppl 2):104–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki T, Sivonen A, Renkonen OV, Savia E, Ylikorkala O. Bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Obstet.Gynecol. 1992;80(2):173–177. available from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macones GA, Parry S, Elkousy M, Clothier B, Ural SH, Strauss JF., III A polymorphism in the promoter region of TNF and bacterial vaginosis: preliminary evidence of gene-environment interaction in the etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2004;190(6):1504–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsby-Baltzer I, Platz-Christensen JJ, Hosseini N, Rosen P. IL-1beta, IL-6, TNFalpha, fetal fibronectin, and endotoxin in the lower genital tract of pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 1998;77(7):701–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Williams SM, Fortunato SJ. Amniotic fluid interleukin-1beta and interleukin-8 concentrations: racial disparity in preterm birth. Reprod.Sci. 2007;14(3):253–259. doi: 10.1177/1933719107301336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Camargo MC, Thorsen P, Lombardi SJ, Fortunato SJ. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6 increase is an indicator of spontaneous preterm birth in white but not black Americans. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2008a;198(1):77. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Thorsen P, Vogel I, Jacobsson B, Morgan N, Jiang L, Li C, Williams SM, Fortunato SJ. Racial disparity in amniotic fluid concentrations of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and soluble TNF receptors in spontaneous preterm birth. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2008b;198(5):533–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Velez DR, Morgan N, Lombardi SJ, Fortunato SJ, Williams SM. Genetic regulation of amniotic fluid TNF-alpha and soluble TNF receptor concentrations affected by race and preterm birth. Hum.Genet. 2008c;124(3):243–253. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myslobodsky M. Preterm delivery: on proxies and proximal factors. Paediatr.Perinat.Epidemiol. 2001;15(4):381–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RB. The consequences for human reproduction of a robust inflammatory response. Q.Rev.Biol. 2004;79(4):383–393. doi: 10.1086/426089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RB, Hillier S, Richter HE, Soper DE, Stamm C, Bass DC, Sweet RL, Rice P. Can known risk factors explain racial differences in the occurrence of bacterial vaginosis? J.Natl.Med.Assoc. 2003;95(3):201–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz-Christensen JJ, Mattsby-Baltzer I, Thomsen P, Wiqvist N. Endotoxin and interleukin-1 alpha in the cervical mucus and vaginal fluid of pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1993;169(5):1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90274-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Avila C, Santhanam U, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin 6 in preterm labor. Association with infection. J.Clin.Invest. 1990;85(5):1392–1400. doi: 10.1172/JCI114583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M, Sparling F, Morrison R. Mucosal immunology of sexually transmitted diseases. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm M, editors. Mucosla Immunology. Elsevier; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Kalinka J. Correlations of selected vaginal cytokine levels with pregnancy-related traits in women with bacterial vaginosis and mycoplasmas. J.Reprod.Immunol. 2008a;78(2):172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Racial differences in cervical cytokine concentrations between pregnant women with and without bacterial vaginosis. J.Reprod.Immunol. 2008b;78(2):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Genetic association of Toll-like receptor 4 with cervical cytokine concentrations during pregnancy. Genes Immun. 2009;10(7):636–640. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver HM, Sperling RS, St Clair PJ, Gibbs RS. Evidence relating bacterial vaginosis to intraamniotic infection. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1989;161(3):808–812. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simhan HN, Caritis SN, Krohn MA, Martinez de TB, Landers DV, Hillier SL. Decreased cervical proinflammatory cytokines permit subsequent upper genital tract infection during pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2003;189(2):560–567. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez DR, Menon R, Thorsen P, Jiang L, Simhan H, Morgan N, Fortunato SJ, Williams SM. Ethnic differences in interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL6 receptor genes in spontaneous preterm birth and effects on amniotic fluid protein levels. Ann.Hum.Genet. 2007;71(Pt 5):586–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez DR, Fortunato SJ, Williams SM, Menon R. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and receptor (IL6-R) gene haplotypes associate with amniotic fluid protein concentrations in preterm birth. Hum.Mol.Genet. 2008;17(11):1619–1630. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZC, Hill JA, Yunis EJ, Xiao L, Anderson DJ. Maternal CD46H*2 and IL1B-511*1 homozygosity in T helper 1-type immunity to trophoblast antigens in recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum.Reprod. 2006;21(3):818–822. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasiela M, Krzeminski Z, Kalinka J, Brzezinska-Blaszczyk E. Correlation between levels of selected cytokines in cervico-vaginal fluid of women with abnormal vaginal bacterial flora. Med.Dosw.Mikrobiol. 2005;57(3):327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SM, Velez DR, Menon R. Geographic ancestry and markers of preterm birth. Expert.Rev.Mol.Diagn. 2010;10(1):27–32. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.