Abstract

Despite a complex cascade of cellular events to reconstruct the damaged extracellular matrix, ligament healing results in a mechanically inferior scarred ligament. During normal healing, granulation tissue expands into any residual normal ligamentous tissue (creeping substitution), resulting in a larger region of healing, greater mechanical compromise, and an inefficient repair process. To control creeping substitution and possibly enhance the repair process, the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-4 (IL-4) was administered to rats prior to and after rupture of their medial collateral ligaments. In vitro experiments demonstrated a time-dependent effect on fibroblast proliferation after interleukin-4 treatment. In vivo treatments with interleukin-4 (100 ng/ml i.v.) for 5 days resulted in decreased wound size and type III collagen and increased type I procollagen, indicating a more regenerative early healing in response to the interleukin-4 treatment. However, continued treatment of interleukin-4 to day 11 antagonized this early benefit and slowed healing. Together, these results suggest that interleukin-4 influences the macrophages and T-lymphocytes but also stimulates fibroblasts associated with the proliferative phase of healing in a dose-, cell-, and time-dependent manner. Although treatment significantly influenced healing in the first week after injury, interleukin-4 alone was unable to maintain this early regenerative response.

Keywords: ligament healing, interleukin-4, mechanical testing, immunohistochemistry, rat

Introduction

Ligament healing involves a complex cascade of events to reconstruct the damaged tissue, encompassing inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling processes. Early wound healing is normally characterized by an up-regulation of neutrophils, macrophages, and T-lymphocytes infiltrating the injury and a concomitant synthesis and degradation of the ECM1. As mediated by the immune cells, fibroblasts arrive in the wound healing region via chemokine signaling, where they synthesize ECM constituents including type I and type III collagens. Simultaneously, macrophage-produced MMPs2 break down collagen, degrading the ECM as part of the remodeling process.1, 2 This coordinated ECM scar-forming response during remodeling lasts months or even years and the injured ligament never fully recovers its original functional properties.3, 4 Numerous reports have examined the influence of biological components on ligament healing, including matrix metalloproteinases,5, 6 cytokines and growth factors,7–10 stem cells,5,11 and platelet-rich plasma.12, 13 To date, no treatment resulted in the complete recovery of the injured ligament. Previous research from our lab characterized the expansion of granulation tissue as “creeping substitution” of the residual ECM.14 Following ligament injury, granulation tissue forms beyond the original injury creeping into the surrounding tissue. The expansion of granulation tissue to replace residual ECM results in further ligament degeneration and an inefficient healing response. A desired healing scenario after injury would have minimal scar tissue, organized collagen fibers, restored concentrations of type I collagen, and limited creeping substitution. Such scenario would reduce type III collagen, and regenerate the ligament with nearly normal composition and mechanical properties.

A localized increase in M1 macrophages that function in tissue debridement, phagocytosis, and MMP synthesis, parallels the onset of creeping substitution and therefore may be a key mediator of the expanding granulation tissue. In contrast, the M2 macrophages promote regeneration by up-regulating anti-inflammatory cytokines. A paucity of M2 macrophages infiltrates the healing ligament. The dominance of M1 over M2 cells may further exacerbate scar formation.

Interleukin-4 (IL-4)3 is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in cell growth, immune system regulation, anti-inflammation, differentiation of T-lymphocytes to Th2 lymphocytes, and promotion of macrophages to the M2 phenotype. Though normally found at low levels in uninjured tissue, IL-4 increases significantly 1 day after injury and peaks at 4 days before decreasing to normal levels by 21 days.15 This up-regulation of macrophage-produced IL-4, results in exaggerated collagen and ECM production by fibroblasts.16, 17 In mouse dermal wounds, daily IL-4 treatments accelerated the formation of granulation tissue and wound closure.15 In contrast, healing was delayed in wounds treated with IL-4-antisense oligonucleotides, although topical IL-4 administration overrode the delay.15 These reported effects led to the present study, which was designed to investigate the potential of IL-4 to improve ligament healing. We hypothesized that IL-4 treatment accelerates healing to control inflammation and reduce scar formation. Our results indicate that IL-4 treatment to the injured ligament reduces wound size, decreases type III collagen, and increases type I procollagen. However, supplementation of IL-4 alone was unable to maintain these effects beyond 5 days or increase healing strength of the ligament.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Fibroblasts from injured and uninjured ligaments were obtained from MCLs at day 5-post injury and from intact rat ligaments as controls. Ligaments were collected from rats that underwent bilateral surgical ruptures of their MCLs described below. Five days post-injury, ligaments were dissected and minced in Hanks’ Balanced Saline Solution using sterile techniques. Intact MCLs were similarly collected and processed. Ligament tissue was digested overnight in filtered 0.5% type IV collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) centrifuged, re-suspended in DMEM4 containing 10% FBS5, expanded in 75 mm2 treated polystyrene flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) and grown to confluence. After reaching confluence, cells were trypsinized, counted and plated at 3 X 103 cells/well in DMEM containing 2% FBS in tissue culture treated Falcon 12-well polystyrene plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 24 hours, fibroblasts obtained from the healing or intact MCLs, were separately treated with recombinant rat IL-4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 0, 0.01, 1, or 100 ng/ml containing DMEM and 2% FBS. Untreated cells (0 ng/ml IL-4) were exposed to medium containing 2% FBS. Treatments were changed every 24 hours. At 24, 48, and 72 hours post-treatment, cell proliferation was determined using MTS6 assay (Cell Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, Madison, WI).

Animals

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Thirty-four skeletally mature male Wistar rats (275–299 g) were used as an in vivo animal model for ligament healing. All rats were purchased with fitted external jugular catheters to enable i.v. treatment administration. Animals were divided into 4 experimental groups based on time of collection and dose of IL-4. In experiment 1, animals were divided into groups of three and subjected to lower doses of 1 ng/ml of IL-4 (LD Day 5)7 or PBS8 i.v. until collection at day 5. For experiment 2, animals were treated with either high doses of 100 ng/ml IL-4 (HD Day 5)9 or PBS i.v. until collection at day 5 (n=3/treatment). Experiment 3 used the same treatments as experiment 2 but then survived the rats until day 11 before collection providing a treated (HD Day 11) and control (PBS) group of animals (n=8/treatment). During all experiments, IL-4 or PBS was administered 2 days prior to surgery (d-2), the day of surgery (d0) and daily thereafter until 4 days post-injury. Finally, experiment 4 animals were treated with i.v. injections of 100 ng/ml IL-4 (Daily Day 11)10 or PBS until the time of sacrifice at day 11 (n=3/treatment). Experiment 4 animals were subjected to IL-4 or PBS injections at d-2 and d0 and daily until 10 days post-injury. Ligaments from 3 animals per treatment in all 4 of the above experiments were collected and used for immunohistochemistry and histology. Another 5 animals/group were included in experiment 3 for mechanical testing. Mechanical testing was not performed on day 5 tissue because the ligament is too compromised for meaningful mechanical data.

Surgical Procedure

Two days prior to surgery, animals were administered IL-4 or PBS via i.v. injections into their previously implanted jugular catheters. Rats were anesthetized (day 0) via isofluorane. Surgical group rats were then subjected to bilateral transactions of their MCL11 s using sterile techniques. MCLs were transected, rather than torn, to create a uniform defect for healing. A small, 1cm skin incision was made over the medial aspect at both the left and right stifles. The subcutaneous tissue was dissected to expose the sartorius muscle and underlying MCL. The axial mid-point of the MCL (determined using a scaled scalpel handle) was completely transected and the muscular, subcutaneous and subdermal tissue layers were each closed with 4–0 Dexon suture. All animals were allowed unrestricted cage movement immediately after surgery. At 5 and 11 days post-injury, animals were sacrificed and the MCLs collected. MCLs were used for immunohistochemistry or mechanical testing.

Tissue harvest

At the time of sacrifice the MCLs used for IHC12 were carefully dissected, measured, weighed, and immediately placed in OCT13 for flash freezing. Longitudinal cryosections were then cut at a 5 μm thickness, mounted on Superfrost plus microscope slides and maintained at −70C. Animals used for mechanical testing, were sacrificed and stored in toto at −70 C until animals were defrosted, MCLs femurs and tibia were dissected, and MCLs were tested.

Histology

Ligament cryosections were H&E14 stained to observe general morphology of the healing ligaments. After staining, images were captured and the granulation tissue regions were measured using Image J.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunostaining was performed on frozen sections using mouse monoclonal or rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Cryosections were fixed 10 minutes with acetone, exposed 5 minutes to 3% hydrogen peroxide to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity, blocked 30 minutes with Background Buster (Innovex Biosciences, Richmond, CA) and incubated with rabbit or mouse primary antibody. Sections were then incubated with biotin, and streptavidin-conjugated to horseradish peroxidase using the Stat Q staining kit (Innovex Biosciences, Richmond, CA). The bound antibody complex was then visualized using DAB15. Stained sections were dehydrated, cleared, cover-slipped and viewed using light microscopy. Negative controls omitting the primary antibody were included with each experiment. Positive controls of gut or spleen were also included.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies to cell surface markers, CD68, CD163, and CD3 were utilized, to identify the following leukocytes, respectively: classically activated macrophages (M1), alternatively activated macrophages (M2), and T-lymphocytes, (all from Abcam-Serotec, Raleigh, NC at a dilution of 1:100). To identify collagen production, type I procollagen (straight; SP1.D8; Developmental Hybridoma, Iowa City, Iowa) and type III collagen (1:8000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) mouse antibodies were used. Endothelial cells were identified using the polyclonal rabbit antibody thrombomodulin (1:2500; American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT) and myofibroblasts were identified using a-smooth muscle actin (straight; Abcam-Serotec, Raleigh, NC).

Quantification

After IHC staining, micrographs were collected using a camera assisted microscope (Nikon Eclipse microscope, model E6000 with an Olympus camera, model DP79). Six blocked random pictures were obtained from each stained cryosection. Images were captured at the HR16, dHR17 and pHR18 edges of the healing region, EL19, and distal and prox20 ends of the MCL (Fig. 1). Two to three sections were counted per animal. Granulation tissue measurements, endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, type I procollagen, and type III collagen were then quantified with Image J (National Institutes of Health). Images captured for T-lymphocytes, and M1 and M2 macrophages were quantified manually.

Figure 1.

Representative cross-section of an H&E-stained healing MCL, indicating the approximate locations subsequent images were captured for later cell enumeration. Two to three sections from each animal were examined accordingly (HR, healing region; pHR, proximal healing region; dHR, distal healing region; prox, proximal; EL, epiligament; Original magnification 40X).

Mechanical Testing

The mechanical behavior of the MCLs was tested to determine the influence of macrophage inhibition on the functional integrity of the healing tissue. Pull-to-failure testing was performed as previously described by Provenzano et al. 18–20 Each MCL was removed with both femoral and tibial insertion sites intact. The surrounding tissue was carefully excised to avoid damaging the insertion sites. During preparation the FMT21 complex was kept hydrated using PBS. The width and thickness of the ligament was measured optically and the cross-sectional area for the ligament was estimated assuming an elliptical cross section. The FMT complex was mounted in a custom testing bath and mechanical testing machine. Optical markers were applied to the ligament on the insertion sites and the tests were recorded. A pre-load of 0.1[N]22 was applied to the ligament and the MCL was preconditioned (cyclically loaded to approximately 1% strain for 10 cycles). Dimensional measurements for the ligament were recorded at the pre-load. The ligament was then pulled to failure at a rate of 10% strain per second.

Failure force, failure stress, and stiffness parameters were all measured to determine ligament functional behavior after treatment. Failure force was recorded as the highest load prior to failure of the ligament and failure stress was calculated by dividing the failure force by the initial cross-sectional area measurements. Failure strain was calculated by dividing the change in ligament length during testing by the initial length of the ligament. Ligament stiffness was defined as the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curve. In the linear region, this number is nearly constant and thus can be calculated by identifying the linear region and average slope.

Statistical Analysis

For cell culture data, a three-way ANOVA23 analysis was implemented to determine the significance of all main effects and interaction effects (up to three-factor interaction). Specifically, the main effect testing included: cell effect (“intact” vs. “day 5”), time effect (“24 hr”, “48 hr”, and “72 hr”), and dose effect (“dose 0,” “dose 0.01”, “dose 1”, and “dose 100”). The interactions, cell*time, cell*dose, time*dose interaction, and cell*time*dose were also tested. The three-way ANOVA analysis of cell* time*dose interactions were insignificant.

Therefore a two-way ANOVA model in which all main effects and three two-factor interactions, i.e. (cell, time), (cell, dose) and (time, dose) was used. A pair wise-contrast F-test was used for testing the pair wise differences between groups.

Ligament regions (Fig. 1) were separately analyzed and pooled into various sub-groups (with underlined names below) to determine any spatial cellular or ECM factor differences. For immunohistochemistry analysis, 2–3 MCL sections per rat were used (3 rats/treatment). Six blocked random regions per section were then counted. The total accounts for the average cell numbers throughout the entire ligament. The MCL includes the average means of all the subgroups excluding the epiligament. The granulation tissue contains the HR, pHR, and dHR regions (Fig 1). The ends include the proximal and distal ligament ends excluding the granulation tissue. Finally, the EL only considers the epiligament measurements. All IHC assays were analyzed using One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to observe for treatment differences (IL-4 and PBS) within the specific sub-groups. Specifically, an F-test was used for testing the overall difference among treatments. A pair wise-contrast F-test was used for testing the pair wise differences between groups. Mechanical testing data were analyzed via t-tests (5 rats/treatment). P < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance of all experiments. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package R-2.9.121

Results

Cell Proliferation

To determine the in vitro dose effects of IL-4 on fibroblasts obtained from healing and injured ligaments, IL-4 was tested on cultured cells. Twenty-four hours post-treatment, fibroblast proliferation from both the injured and intact ligament significantly increased at all concentrations tested (0.01, 1 and 100 ng/ml IL-4; Fig. 2). At 48 hours, IL-4 did not significantly influence fibroblast proliferation from the intact ligament cells. In contrast, all tested concentrations of IL-4 inhibited proliferation in injured ligament fibroblasts. No effects were observed at 72 hours, regardless of cell-type (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Dose response of IL-4 on fibroblast proliferation from cells obtained from uninjured (A) or day 5 post-injured ligaments (B). Cells were collected at 24, 48 and 72 (not shown) hours post-treatment and quantified.

Low dose (1ng/ml) IL-4 Results

In vivo administration of 1 ng/ml IL-4 (experiment 1; n= 3 rats/treatment) resulted in no significant differences in granulation tissue area, M2 macrophages, T-lymphocytes, procollagen, type III collagen, or endothelial cells between the PBS controls. Only the M1 macrophages within the epiligament were significantly different after IL-4 treatment. Based on these low dose results, a higher dose of IL-4 (100 ng/ml) was tested in vivo for experiments 2–4.

Morphological measurements/granulation tissue size

To determine the in vivo influence of IL-4 on ligament healing were used to measure granulation tissue. Size of granulation tissue was normalized to the total ligament area. High doses of IL-4 significantly decreased granulation tissue size (p = .049) at day 5 (Fig. 3; Fig 6A–B). No other significant effects were observed.

Figure 3.

Graph of granulation tissue size after IL-4 treatment (n=3 rats/treatment; 21 total rats). High doses of IL-4 significantly reduced the normalized healing region at day 5 (p < .05). No other significant treatment effects were observed at day 11 or with low-doses of IL-4. Values are the mean percentage of the granulation tissue area divided by the total ligament area ± S.E.M.

Figure 6.

Representative micrograph of H&E (A–B), Type I procollagen (C–F) and Type III collagen (G–H) after PBS (left column) or IL-4 (right side) treatment. Size of the day 5 granulation tissue after PBS (A) or IL-4 (B) treatment. Black circles are the same size to compare the granulation size differences between the two groups (A–B). Type I procollagen IHC of the day 5 ligament after treatment with PBS (C) or high doses of IL-4 (D). Type I procollagen IHC of the day 11 ligament after PBS treatment (E) or daily high doses of IL-4 (F). Type III collagen IHC of the day 5 ligament after PBS (G) or high doses of IL-4 (H) treatment.

Macrophages and T-lymphocytes

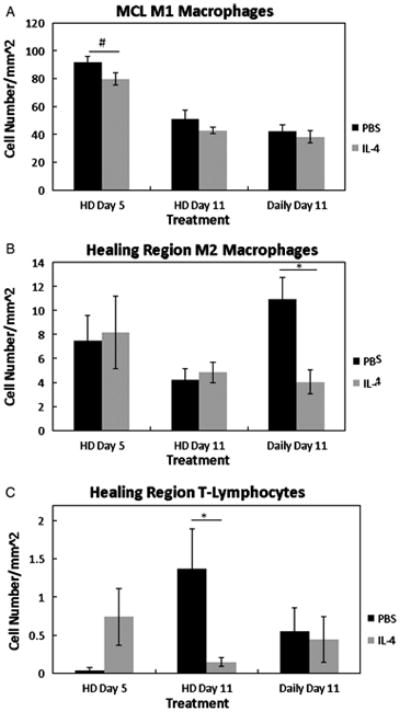

Because the probable targets of IL-4 mediated immune suppression are the T-lymphocyte and macrophage, these cell types were evaluated after IL-4 treatment (Fig. 4). The number of M1 macrophages was reduced within the epiligament (p = .001) after low dose IL-4 (103.1± 9.5 cells/mm2 PBS vs. 47.1 ± 8.3 cells/mm2 IL-4) treatment (data not shown). Administering a higher dose of IL-4 tended to decrease the MCL M1 macrophages at day 5 (p =.078), but no other experimental groups or time points were significantly altered (Fig. 4A). On day 5 the number of M2 cells was not significantly altered after IL-4 treatment, but daily doses of IL-4 decreased (p = .004) the number of M2 cells at within the granulation tissue day 11 (Fig. 4B). A paucity of T-lymphocytes was identified in the ligament regardless of treatment (Fig 4C). IL-4 did not significantly influence T-lymphocytes numbers at day 5 (p > .05). However, T-lymphocytes numbers were diminished in the granulation tissue of the day 11 ligament from experiment 3 (Fig 4C; p = .03).

Figure 4.

Graph of the M1 macrophages (A), M2 macrophages (B), and T-lymphocytes (C), at 5 and 11 days post-injury after PBS or IL-4 treatment (n=3 rats/treatment; 21 total rats). On day 5, high doses of IL-4 (HD Day 5) tended to reduce the MCL M1 macrophages (p =.078; A). No differences within the MCL were observed at any other points. The day 11 healing region M2 macrophages were significantly reduced after continuous treatment of IL-4 (Daily Day 11;B). High doses of IL-4 (HD Day 5) reduced the number of healing region T-lymphocytes at day 11.#Indicates a trend (p < .1 between PBS and IL-4 at day 5. * Indicates significance (p< .05) between PBS and IL-4 at day 11 (C). Values are expressed as mean cell numbers ± S.E.M.

Type I and III pro/collagen

To determine whether IL-4 influences the primary collagens involved in ligament healing, collagen type I and III were analyzed. Type I procollagen increased significantly (p = .03) in the day 5 ligament after treatment of high dose IL-4 (Fig. 5A, Fig 6). Concomitantly, type III collagen MCL levels decreased (p = .003) in response to IL-4 treatment (Fig 5B, Fig. 6). This modification of the normal healing process was transient, however. After cessation of IL-4 treatment, no other treatment effects were observed with type I or III collagen on day 11. Continuation of IL-4 treatment resulted in detrimental effects on collagen production. Daily doses decreased procollagen type I (p = .057) while maintaining type III collagen (p = .15) which is abundant in scar formation. These results agree with the in vitro data indicating time-dependent effects of IL-4 on fibroblast proliferation.

Figure 5.

Graph of type I procollagen (A) and type III collagen (B) after PBS and IL-4 treatment (n=3 rats/treatment; 21 total rats). High doses of IL-4 (HD Day 5) significantly increased type I procollagen (A) and decreased type III collagen (B) at day 5 within the MCL. However, daily doses of IL-4 (Daily Day 11) reduced type I collagen (p= .057; A). No other effects were observed with type III collage at day 11 (B).*Indicates significant difference (p < .05) between PBS and IL-4 at day 5 (A, B) or day 11 (A). #Indicates a trend (p < 0.1 between PBS and IL-4 at day 11 (Daily Day 11). Values are expressed as mean positive staining ± S.E.M.

Endothelial Cells

Studies in other tissues report an inhibitory influence of IL-4 on angiogenesis. 22,23 Therefore, we investigated endothelial cell localization using IHC. In the day 5 specimens, a high dose of IL-4 increased the average number of endothelial cells within the epiligament (p = .01; data not shown). No other day 5 effects were observed. In contrast, IL-4 significantly reduced the number of MCL endothelial cells in both day 11 groups (HD day 11: p = .03; Daily day 11: p = .01) when compared to PBS controls (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Response of endothelial cells (A) and myofibroblasts (B) to PBS or IL-4 (n=3 rats/treatment; 21 total rats). No treatment effects were observed at day 5 (A, B). In contrast IL-4 significantly reduced the number of MCL endothelial cells at day 11 (A). Healing region myofibroblasts were also reduced with daily doses of IL-4 at day 11 whereas injections up to day 4 were not effective (B). *Indicates significant difference (p < .05) between PBS and IL-4 at day 11 (A, B). Values are expressed as mean positive staining ± S.E.M.

Myofibroblasts

Myofibroblasts are differentiated fibroblasts known to aid in wound contraction. The low dose IL-4 treatment group exhibited no discernable effects so this group was omitted from further testing. No significant difference (p > .05) in of granulation tissue-localized myofibroblasts was found in the day 5 or day 11 high dose group when compared to PBS controls (Fig. 7B). However, daily administration of IL-4 decreased the number myofibroblasts (p = .03).

Spatial Localization of IHC Factors

To target any cellular or ECM spatial differences after IL-4 treatment, the total ligament, MCL body, granulation tissue region, extraneous granulation tissue region and the epiligament were individually analyzed. Treatment primarily affected IHC factors within the granulation tissue, including the T-lymphocytes, type I procollagen, endothelial cells, M2 macrophages, and myofibroblasts. IL-4 was less influential within the epiligament and uninjured ligament regions; effecting only endothelial cells and M1 cells within the epiligament, and type I procollagen and type III collagen within the uninjured regions.

Mechanical testing

To determine if IL-4 treatment affected ligament function, the day 11 samples (HD day 11) (Fig. 8) were mechanically tested. Ligament failure force, failure stress, and stiffness were measured. No significance difference was found between IL-4 treated specimens and the PBS control for any parameter tested (p > .05). These results therefore suggest that IL-4 treatment did not reduce the mechanical properties of the healing ligament or inhibit functional recovery.

Figure 8.

Failure force (A), failure stress (B), and stiffness (C) to response to PBS or IL-4 treatment 11 days post-injury(n=5 rats/treatment; 10 total rats). No significance in failure force (A) failure stress (B) or stiffness (C) was observed. P > .05. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

Discussion

We hypothesized that IL-4 treatment would accelerate healing by controlling inflammation and reducing scar formation. Results indicate beneficial, albeit transient effects of IL-4 on ligament healing. The in vitro study reveals a time-dependent effect of IL-4 on fibroblasts obtained from normal and injured tissue. It also shows different behaviors in fibroblasts from normal and injured tissues. In vivo administration of IL-4 stimulates early biological healing in a dose-dependent manner without degrading mechanical recovery compared to normal healing. Finally, continued IL-4 treatment negates the early benefits in the observed healing response.

IL-4 is known to control the inflammatory response by modulating the inflammatory M1/Th1 cells towards a M2/Th2 pathway, respectively. In the current study at day 5, high doses of IL-4 accelerated in vivo ligament repair by reducing wound size, stimulating type I procollagen and inhibiting type III collagen. High doses of IL-4 also tended to reduce M1 macrophages and increase T-lymphocytes without affecting the number of myofibroblasts or endothelial cells. However, the in vivo and in vitro results consistently demonstrated a time-limited response to IL-4. After 24 hours, IL-4 stimulated the in vitro proliferation of fibroblasts from tissue obtained from injured and uninjured tissue. In contrast, fibroblasts collected from the injured ligament were inhibited by IL-4 after 48 hours, and cells from the uninjured ligament were not. Similarly, in vivo IL-4 administration up to 4 days beyond injury showed early regenerative effects (observed at day 5), but these effects were lost by day 11.

In an attempt to sustain the regenerative effects of IL-4, an experiment was performed in which IL-4 was administered daily until the time of collection at day 11 with the expectation that sustained IL-4 treatment would maintain the regenerative response. Studies administering IL-4 to chronic inflammatory models support this hypothesis. For example, Horsfall et al.24 administered daily IL-4 treatments to a collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model. CIA results in a chronic macrophage response, coinciding with enhanced tissue damage. Daily IL-4 treatments suppressed CIA for 28 days. Once IL-4 treatments were halted, arthritis resumed, inflammation elevated and treated joints were comparable to the controls.4 These results suggest that IL-4 acts on the persistently produced macrophages that are common to chronic inflammatory conditions.25 Discontinuing IL-4 treatments no longer provided the necessary signals to control the immune cell response, thus enabling chronic inflammation to resume.25 Our results indicate that continuous IL-4 administration beyond inflammation did not maintain the regenerative response and in fact inhibited healing and cell proliferation as confirmed by the in vivo experiment 4 and the in vitro 48 hour experiments, respectively. These results suggest that IL-4 accelerates healing during the inflammatory phase but is unable to sustain the repair response beyond the inflammatory phase of healing at the concentrations of IL-4 tested in this study.

IL-4 is known to influence macrophages and T-lymphocytes during inflammation but our in vitro and in vivo results indicate that IL-4 also influences MCL fibroblasts. Fibroblasts contain high affinity IL-4 receptors and express collagen after IL-4 stimulation.26–28 Huaux et al.29 reported a dual role for IL-4, suggesting that IL-4 acts on the immune cells during early inflammation and on fibroblasts during fibrosis. Although our study only found a tendency for IL-4 to reduce macrophage numbers, treatment may have altered the macrophage-induced cytokine release. Numerous studies confirm the ability of IL-4 to block mononuclear phagocytic cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.30–32 In this capacity, IL-4 may play a beneficial role by limiting early inflammatory signals, but may also play a detrimental role by promoting scarring after macrophages subside. Additionally, IL-4 may also influence the T-lymphocytes in our wound healing model. At day 11, daily doses of IL-4 significantly reduced the number of T-lymphocytes, possibly signifying a regenerative role for the few T-lymphocytes found in the ligament. The signals that govern regeneration versus scar during early and late healing are not fully understood but are believed to be a coordinated response between macrophages, T-lymphocytes, and fibroblasts.

The discrepancy in the IL-4-induced proliferative response between fibroblasts obtained from injured ligament and fibroblasts obtained from uninjured ligament is a new finding. During the first 24 hours post-treatment, fibroblasts from intact and injured ligaments responded to all doses of IL-4 tested. By 48 hours post-treatment, IL-4 treatment inhibited fibroblast proliferation from injured tissue but was not effective on fibroblasts from uninjured tissue. The difference in cell response to IL-4 may be attributed to a change in IL-4 receptor number, a change in affinity of IL-4 to its receptor, the change in cytokine environment induced by the wound healing response or the difference in receptor internalization or processing mechanisms to induce proliferation. Further studies are required to test these concepts.

A desired healing scenario after injury would regenerate the ligament with nearly normal composition, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Although IL-4 promoted early ligament healing, treatment with this factor failed to improve mechanical or functional properties. The current results suggest that treatment of multiple IL-4 bolus injections to the injured ligament is insufficient to suppress scar tissue formation and improve mechanical properties during healing. A number of investigators reported enhanced biological responses after exogenous growth factor/cytokine treatment but only a few demonstrated increased healing strength 7–10,33. Continual release of a cytokine treatment rather than a bolus injection with a limited half life may increase efficacy and improve the healing outcome. Thomopolous et al. demonstrated enhanced biological tendon healing after bFGF treatment, but no improvement in healing strength34. In contrast, gene transfer of bFGF, resulting in controlled delivery, improved tendon healing strength.33 In our lab, Provenzano et al. showed increases in healing tissue strength with IGF-1 and GH.35 These results suggest that not only the type and concentration of the cytokine/growth factor delivered, but the time, duration, and method of delivery influence healing outcome and mechanical behavior.

The current study also compared the spatial differences of the tested factors between the MCL, epiligament, healing regions, and uninjured regions after IL-4 treatment. The effects of IL-4 were primarily observed within the granulation tissue of the healing ligament whereas few cellular changes occurred within the epiligament or the uninjured regions. Ligament vascularity, cellular differentiation, phagocytosis, and collagen synthesis is primarily localized to the epiligament, during normal healing.36–39 However, the current results imply that IL-4 influences the fibroblasts and/or immune cells within the ligament body, suggesting a direct influence of IL-4 on the MCL.

Numerous reports have confirmed macrophage-induced cytokine modulation, but this study did not. The current study was not focused on which cells IL-4 influenced, but rather if IL-4 affected ligament healing via structural and compositional criteria. Furthermore, fibroblasts were only studied for the dose-dependent effects of IL-4. Certainly, the influence of macrophages, T-lymphocytes and the co-culture of these cells with fibroblasts would provide additional information about the specific cellular dose-response of IL-4.

In summary, IL-4 enhances ligament regeneration during the early phase of MCL healing. With administration of IL-4, the normally high production of type III collagen in the healing tissue was reduced while type I procollagen was stimulated. The response appears more regenerative of native tissue. However, IL-4 was insufficient to maintain these regenerative effects throughout the remodeling phase of tissue healing, suggesting that other downstream factors must be considered and modulated in order to achieve regenerative healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant Nos. AR049266 and AR059916.

Footnotes

ECM: extracellular matrix

MMP: matrix metalloproteinase

IL-4: interleukin-4

DMEM: Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

FBS: fetal bovine serum

MTS: [3-(4,5-dimethylthizaol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt]

LD Day 5: low-dose IL-4 day 5

PBS: phosphate buffered saline

HD Day 5: high dose IL-4 day 5

Daily Day 11: daily IL-4 injections day 11

MCL: medial collateral ligament

IHC: immunohistochemistry

OCT: optimal cutting temperature

H&E: hematoxylin and eosin

DAB: diaminobenzidine

HR: healing region

dHR: distal healing region

pHR: proximal healing region

EL: epiligament

Prox: proximal

FMT: femur-MCL-tibia

N: Newtons

ANOVA: analysis of variance

References

- 1.Clark RA, Nielsen LD, Welch MP, McPherson JM. Collagen matrices attenuate the collagen-synthetic response of cultured fibroblasts to TGF-beta. Journal of cell science. 1995;108 (Pt 3):1251–1261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levenson SM, Geever EF, Crowley LV, Oates JF, 3rd, Berard CW, Rosen H. The healing of rat skin wounds. Annals of Surgery. 1965;161:293–308. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196502000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ. Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair. Journal of Biomechanics. 2004;37:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnabel LV, Lynch ME, van der Meulen MC, Yeager AE, Kornatowski MA, Nixon AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and insulin-like growth factor-I gene-enhanced mesenchymal stem cells improve structural aspects of healing in equine flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2009;27:1392–1398. doi: 10.1002/jor.20887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedi A, Fox AJ, Kovacevic D, Deng XH, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. Doxycycline-mediated inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases improves healing after rotator cuff repair. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38:308–317. doi: 10.1177/0363546509347366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy PG, Loitz BJ, Frank CB, Hart DA. Influence of exogenous growth factors on the expression of plasminogen activators by explants of normal and healing rabbit ligaments. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire. 1993;71:522–529. doi: 10.1139/o93-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spindler KP, Dawson JM, Stahlman GC, Davidson JM, Nanney LB. Collagen expression and biomechanical response to human recombinant transforming growth factor beta (rhTGF-beta2) in the healing rabbit MCL. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2002;20:318–324. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mammoto T, Seerattan RA, Paulson KD, Leonard CA, Bray RC, Salo PT. Nerve growth factor improves ligament healing. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2008;26:957–964. doi: 10.1002/jor.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scherping SC, Jr, Schmidt CC, Georgescu HI, Kwoh CK, Evans CH, Woo SL. Effect of growth factors on the proliferation of ligament fibroblasts from skeletally mature rabbits. Connective tissue research. 1997;36:1–8. doi: 10.3109/03008209709160209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe N, Woo SL, Papageorgiou C, Celechovsky C, Takai S. Fate of donor bone marrow cells in medial collateral ligament after simulated autologous transplantation. Microscopy research and technique. 2002;58:39–44. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray MM, Palmer M, Abreu E, Spindler KP, Zurakowski D, Fleming BC. Platelet-rich plasma alone is not sufficient to enhance suture repair of the ACL in skeletally immature animals: An in vivo study. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2009;27:639–645. doi: 10.1002/jor.20796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray MM, Spindler KP, Abreu E, Muller JA, Nedder A, Kelly M, Frino J, Zurakowski D, Valenza M, Snyder BD, Connolly SA. Collagen-platelet rich plasma hydrogel enhances primary repair of the porcine anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2007;25:81–91. doi: 10.1002/jor.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain CS, Crowley E, Vanderby R. The spatio-temporal dynamics of ligament healing. Wound repair and regeneration: official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2009;17:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmon-Ehr V, Ramont L, Godeau G, Birembaut P, Guenounou M, Bernard P, Maquart FX. Implication of interleukin-4 in wound healing. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2000;80:1337–1343. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buttner C, Skupin A, Reimann T, Rieber EP, Unteregger G, Geyer P, Frank KH. Local production of interleukin-4 during radiation-induced pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis in rats: Macrophages as a prominent source of interleukin-4. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1997;17:315–325. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.3.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando M, Miyazaki E, Fukami T, Kumamoto T, Tsuda T. Interleukin-4-producing cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An immunohistochemical study. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 1999;4:383–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.1999.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provenzano PP, Heisey D, Hayashi K, Lakes R, Vanderby R., Jr Subfailure damage in ligament: A structural and cellular evaluation. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md: 1985) 2002;92:362–371. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Provenzano PP, Martinez DA, Grindeland RE, Dwyer KW, Turner J, Vailas AC, Vanderby R., Jr Hindlimb unloading alters ligament healing. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md: 1985) 2003;94:314–324. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00340.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Provenzano PP, Rueden CT, Trier SM, Yan L, Ponik SM, Inman DR, Keely PJ, Eliceiri KW. Nonlinear optical imaging and spectral-lifetime computational analysis of endogenous and exogenous fluorophores in breast cancer. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2008;13:031220. doi: 10.1117/1.2940365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Development Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas CS, Amin MA, Allen BB, Ruth JH, Haines GK, 3rd, Woods JM, Koch AE. Inhibition of angiogenesis by interleukin-4 gene therapy in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54:2402–2414. doi: 10.1002/art.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpert OV, Fong T, Koch AE, Peterson JD, Waltenbaugh C, Tepper RI, Bouck NP. Inhibition of angiogenesis by interleukin 4. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:1039–1046. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horsfall AC, Butler DM, Marinova L, Warden PJ, Williams RO, Maini RN, Feldmann M. Suppression of collagen-induced arthritis by continuous administration of IL-4. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1997;159:5687–5696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger D, Dayer JM. The role of human T-lymphocyte-monocyte contact in inflammation and tissue destruction. Arthritis research. 2002;4 (Suppl 3):S169–76. doi: 10.1186/ar558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowenthal JW, Castle BE, Christiansen J, Schreurs J, Rennick D, Arai N, Hoy P, Takebe Y, Howard M. Expression of high affinity receptors for murine interleukin 4 (BSF-1) on hemopoietic and nonhemopoietic cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1988;140:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Postlethwaite AE, Holness MA, Katai H, Raghow R. Human fibroblasts synthesize elevated levels of extracellular matrix proteins in response to interleukin 4. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1992;90:1479–1485. doi: 10.1172/JCI116015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillery P, Fertin C, Nicolas JF, Chastang F, Kalis B, Banchereau J, Maquart FX. Interleukin-4 stimulates collagen gene expression in human fibroblast monolayer cultures. potential role in fibrosis. FEBS letters. 1992;302:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80448-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huaux F, Liu T, McGarry B, Ullenbruch M, Phan SH. Dual roles of IL-4 in lung injury and fibrosis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2003;170:2083–2092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen JB, Wong HL, Costa GL, Bienkowski MJ, Wahl SM. Suppression of monocyte function and differential regulation of IL-1 and IL-1ra by IL-4 contribute to resolution of experimental arthritis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1993;151:4344–4351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vannier E, Miller LC, Dinarello CA. Coordinated antiinflammatory effects of interleukin 4: Interleukin 4 suppresses interleukin 1 production but up-regulates gene expression and synthesis of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:4076–4080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miossec P, Briolay J, Dechanet J, Wijdenes J, Martinez-Valdez H, Banchereau J. Inhibition of the production of proinflammatory cytokines and immunoglobulins by interleukin-4 in an ex vivo model of rheumatoid synovitis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1992;35:874–883. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang JB, Cao Y, Zhu B, Xin KQ, Wang XT, Liu PY. Adeno-associated virus-2-mediated bFGF gene transfer to digital flexor tendons significantly increases healing strength. an in vivo study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2008;90:1078–1089. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomopoulos S, Kim HM, Das R, Silva MJ, Sakiyama-Elbert S, Amiel D, Gelberman RH. The effects of exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor on intrasynovial flexor tendon healing in a canine model. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2010;92:2285–2293. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Provenzano PP, Alejandro-Osorio AL, Grorud KW, Martinez DA, Vailas AC, Grindeland RE, Vanderby R., Jr Systemic administration of IGF-I enhances healing in collagenous extracellular matrices: Evaluation of loaded and unloaded ligaments. BMC physiology. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnoczky SP, Matyas JR, Buckwalter JA, Amiel D. The anterior cruciate ligament: Current and future concepts. New York: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woo Savio L-Y, Abramowitch SD, Kilger R, Liang R. Biomechanics of knee ligaments: Injury, healing, and repair. J Biomechanics. 2006;39:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo SLY, An KN, Arnoczky SP, et al. Anatomy, biology, and biomechanics of tendon, ligament, and meniscus. In: Simon SR, editor. Ortopaedic basic science. Rosemont: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1994. pp. 45–88. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo IK, Ou Y, Rattner JP, Hart DA, Marchuk LL, Frank CB, Rattner JB. The cellular networks of normal ovine medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments are not accurately recapitulated in scar tissue. Journal of anatomy. 2002;200:283–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]