Abstract

Functional anti-N. meningitidis serogroup A (MenA) activity in human serum is detected by serum bactericidal assay (SBA), using either rabbit (rSBA) or human (hSBA) complement, with F8238 as the recommended MenA SBA target strain. However, the F8238 strain may not be optimal for this purpose because, as we show here, it expresses the L11 immunotype, whereas most MenA invasive strains express the L(3,7)9 or L10 immunotype. Moreover, SBA results may be strain dependent, because immunotypes differ in their sensitivity to complement, emphasizing the need to choose the most appropriate strain. Sera from random subsets of infants, toddlers, children, and adolescents in clinical trials of MenA conjugate vaccines were tested by rSBA using strains 3125 (L10) and F8238 (L11). In unvaccinated subjects from all age groups, the percentages of seropositive samples (rSBA-MenA titer, ≥1:8) was lower using strain 3125 than using strain F8238. However, in toddlers and adolescents immunized with a conjugate MenA vaccine, the percentages of seropositive samples generally were similar using either strain in the rSBA. In two studies, sera also were tested with hSBA. Using hSBA, the differences in the percentages of seroprotective samples (hSBA-MenA titer, ≥1:4) between strains 3125 and F8238 was less apparent, and in contrast with rSBA, the percentage of seroprotective samples from unvaccinated subjects was slightly higher using strain 3125 than using strain F8238. In adults vaccinated with plain MenA polysaccharide, the percentage of seroprotective samples was higher using strain 3125 than with strain F8238, and the vaccine response rates using strain 3125 were better aligned with the demonstrated efficacy of MenA vaccination. In conclusion, SBA results obtained using the MenA L10 3125 strain better reflected vaccine-induced immunity.

INTRODUCTION

The development of effective polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines targeting Neisseria meningitidis relies upon the measurement of bactericidal antibodies (4, 32). To ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of N. meningitidis serogroup A (MenA) conjugate vaccines, the WHO recommends the use of any MenA strain in the serum bactericidal assay (SBA), provided that the strain is not killed by the complement in the absence of MenA-specific antibodies (33). However, strain A1, originally used by Goldschneider et al. in their classic studies (8), was shown to be too sensitive to complement killing (20). The SBA against MenA that has been proposed by Maslanka et al. (20) uses rabbit complement and MenA strain F8238.

Clinical trials with MenA polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines showed a high percentage of control subjects, not vaccinated with a MenA vaccine, who became SBA positive (with rabbit complement 2nd strain F8238) between 18 weeks of age and the second year of life (5). However, these subjects did not display a parallel increase in anti-capsular polysaccharide A IgG, suggesting that part of the positive SBA results, referred to as natural immunity, was related to either noncapsular surface antigens or to IgM antibodies against polysaccharide A. Such an observation indicates that the F8238 rabbit complement-based SBA is not optimal to detect the presence of vaccine-induced anti-MenA immunity.

N. meningitidis is subdivided into immunotypes based on the structure of their lipooligosaccharide (LOS). Twelve different structures are known, denominated L1 through L12 (28). These immunotypes may give distinct immunological properties to the bacteria, and this phenomenon has been well studied in N. meningitidis serogroup B (MenB). For example, MenB LOS immunotypes were shown to be associated with virulence and were different between case and carrier isolates. Most case isolates are L3,7, whereas most carrier isolates are L8 (14). The structural difference between the L3,7 and L8 LOS types is determined by the size of the alpha chain, which is shorter for the L8 immunotype (28). L8 cannot be sialylated, in contrast to L3,7. As a direct consequence of this structural difference, L8-type MenB strains are more complement sensitive, which has an effect on SBA results (21).

Based on the observations that the LOS type affects the sensitivity of MenB strains to complement, we considered that the same may apply to MenA strains and that the LOS type of MenA strains may affect the SBA sensitivity. Hence, the MenA SBA may be improved in two ways: by reducing the sensitivity in detecting natural immunity and by increasing the correlation between seropositivity and the observed efficacy after polysaccharide vaccination. Therefore, the LOS types of different MenA strains were determined, and two MenA strains, reference strain F8238 and strain 3125, representing different LOS immunotypes, were evaluated by SBA using either rabbit (rSBA) or human (hSBA) complement. This evaluation was carried out with serum samples from clinical trials involving infants, older children, and adolescents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The A1 and F8238 strains were provided by E. Gotschlich (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) and by the CDC (Atlanta, GA), respectively. L10 MenA strains, including the 3125 strain, were provided by C. T. P. Hopman, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Sequence typing of strain 3125 (performed by the Health Protection Agency, United Kingdom) revealed that it belongs to ST-7776 within the ST-1 clonal complex (serotype NT, serosubtype P1.5,2), and it has been characterized in the present study as immunotype L10. F8238 belongs to the ST-5 clonal complex (serotype 4.21, serosubtype P1.20,9), and it has been characterized as immunotype L11.

Tricine gels to separate LOS immunotypes.

Frozen N. meningitidis vials were thawed, and 0.1 ml of sample was streaked onto a petri dish filled with Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Bacteria were lifted using a loop resuspended in water and inactivated for 15 min at 96°C before proteinase K treatment (20 mg/ml for 2 h at 60°C; Sigma). Prior to being loaded, samples in tricine buffer were denatured for 5 min at 100°C. Tricine–SDS-PAGE was performed in 4% stacking and 16% separating minigels (1-mm gel; Novex). Gels were fixed overnight in 40% ethanol, 5% acetic acid solution and silver stained as described by Tsai and Frasch (31). Finally, a stop reaction as described by Hitchcock and Brown (10) was performed.

Study subjects.

Serum samples were taken from subjects enrolled in five clinical trials of MenA conjugate or polysaccharide vaccines (Table 1). All vaccines were manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium, except the MenC-CRM197 conjugate vaccine, which is manufactured by Wyeth.

Table 1.

Description of the studies

| Study (country) | Study designation | Design | Age of subjects | Vaccination schedule | Time of blood sample collection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, phase II (Philippines) | 759346/001-002, NCT00317174 | Open, randomized | 6–10 wk | 3 Doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC (TT conjugate)a or DTPw-HBV + Hibb,c | 1 mo after completion of vaccination and at 10 mo in a randomized subset | 5 |

| B, phase II (Ghana) | 104430/ISRCTN3575408 | Double blind, randomized | 6–10 wk | Primary: 3 doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC (TT-conjugate)a or DTPw-HBV/Hiba,c | 1 mo after completion of primary vaccination, prior to, and 1 month after booster | 11 |

| 12 mo | Booster: 1/5 dose of MenAC (PS)d | |||||

| C, phase III (Thailand) | 104727, NCT00136604 | Partially blinded, controlled | Infancy | Primery: 3 doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC (TT-conjugate)a or DTPw-HBV/Hiba,c | Prior to and 1 month after booster | 15 |

| 15–24 mo | Booster: DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC (TT conjugate)a | |||||

| D, phase II (Denmark) | 104702, NCT00126945 | Randomized, partially blinded | 15–19 yr | 1 Dose of investigational MenACWY (TT conjugate) or MenACWY (PS)e | Prior to and 1 month after vaccination | 23 |

| E, phase II (Germany and Austria) | 104703, NCT00126984 | Randomized, partially blinded | 12–14 mo or 3–5 y | 1 Dose of investigational MenACWY (TT conjugate), MenC (CRM197 conjugate)f (age 12–14 mo), or MenACWY (PS)e (age 3–5 yr) | Prior to and 1 month after vaccination | 17 |

Both vaccines were mixed extemporaneously.

Both vaccines were administered separately.

TritanrixHepB (GSK)/Hiberix (GSK).

Mencevax AC (GSK).

Mencevax ACWY (GSK).

Meningitec (Wyeth).

Samples from all subjects with available sera were assessed. Sera were stored at −20°C prior to blinded analysis at laboratories of GSK Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium.

Previous or intercurrent meningococcal disease and vaccination with a meningococcal vaccine were exclusion criteria in all studies. In all studies, written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians of subjects and from subjects (where applicable) before enrolment. Study protocols were approved by overseeing ethics committees. All of the studies were conducted according to Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Serological assays.

Sera from children and adolescents who participated in studies A to E were tested by rSBA (20) using the 3125 (L10 immunotype) or the F8238 (L11 immunotype) strain. This was planned on all sera available, except for studies A and B, for which the 3125 strain was tested post hoc, and in study B the 3125 rSBA was done in a randomized subset of 60% of the subjects only. The cutoff of the rSBA was a 1:8 dilution, above which the samples were defined as seropositive. Sera from studies C to E also were tested post hoc, using hSBA with the 3125 (studies C to E) or the F8238 (studies D and E) strain, with the cutoff being a 1:4 dilution, which is considered indicative of protection (8). SBA geometric mean antibody titers (GMTs) derived from each assay also were calculated.

The SBAs were performed according to the Maslanka method (20), with some modifications, using frozen strain 3125 working seeds and fresh strain F8238 seeds. Briefly, fresh or thawed cells were mixed with either rabbit or human complement and with serial dilutions of the tested serum. The killing reaction was performed in 96-well plates for 90 min at 37°C. The mixture then was overlaid with agar and incubated for 16 to 20 h at 35°C. The number of CFU was counted with an automatic counter, and the bactericidal titer for each serum was expressed as the reciprocal serum dilution corresponding to 50% killing.

IgG antibodies to meningococcal polysaccharide A (PSA) were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (cutoff for positivity, 0.30 μg/ml) in all studies (6) and expressed as geometric mean concentrations (GMC, in μg/ml).

Statistical analysis.

The correlation between postvaccination results using the L11- and L10-based SBAs with human and rabbit complement in studies D and E was depicted graphically, where r denotes the coefficient of correlation. The concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) is defined as the product of correlation and accuracy (18).

Vaccine response was defined as a postvaccination titer of ≥32 (rSBA) or ≥8 (hSBA) in initially seronegative subjects (<8 rSBA and <4 hSBA) and a ≥4-fold increase in titer from pre- to postvaccination in initially seropositive subjects, as recommended by the WHO in 2006 (33).

RESULTS

Selection of a new MenA strain.

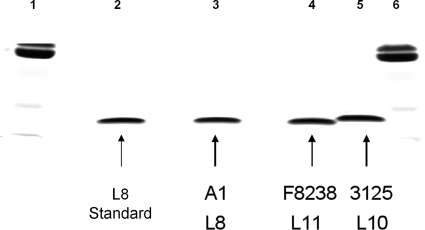

When selecting a strain for SBA for vaccine evaluation, it is important that the strain is resistant to non-antibody-mediated complement killing. The 3125 strain was selected to fulfill this criterion. Moreover, using adsorbed rabbit polyclonal antibodies and immunoprecipitation (assays conducted by C. T. P. Hopman, University of Amsterdam, Department of Medical Microbiology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; data not shown) (8, 20, 24) and Tricine–SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1), the LOS immunotypes of the A1, F8238, and 3125 meningococcal strains were confirmed to belong to immunotypes L8, L11, and L10, respectively. Based on these confirmations, strain 3125 was selected to develop new SBAs.

Fig. 1.

LOS analysis of Neisseria meningitidis strains in a 16% polyacrylamide Tricine gel. Lanes 1 and 6, multimarker; lane 2, L8 immunotype standard, purified; lane 3, MenA A1 (L8); lane 4, MenA F8238 (L11); lane 5, MenA 3125 (L10).

A review of the literature showed that most invasive MenA strains belong to either the L10 or the L(3,7)9 immunotype, whereas the L11 immunotype is more likely to be associated with carrier strains (Table 2), which confirmed the choice of the 3125 strain to develop new SBAs. This is in line with observations made for serogroup B, because immunotypes associated with MenA carriage strains (L11 LOS) display shorter alpha chains than the L10 strains associated with invasive strains, as evaluated by mass spectrometry (data not shown) and by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). Hence, SBAs using 3125 strain (L10-SBA) were compared with the SBAs using the currently recommended F8238 strain (L11-SBA).

Table 2.

Assignment of immunotype to 498 N. meningitidis serogroup A strainsa

| Classification method (reference) | No. of N. meningitidis serogroup A strains by type |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive |

Carrier |

||||||||||||

| Origin of isolate | L(3,7)9 | L10 | L11 | L10,11 | Other | ND | Origin of isolate | L(3,7)9 | L10 | L11 or L10,11 | Other | ND | |

| SDS-PAGE against mouse MAbs (16) | China | 2 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| United States | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Others | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||

| Western blotting with SDS-PAGE against both mouse monoclonal antibodies and reference hyperimmune rabbit sera (25) | Sudan | 1 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||||||

| Sweden | 9 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Western blotting with SDS-PAGE against both mouse monoclonal antibodies and reference hyperimmune rabbit sera (1) | Various | 154 | 122 | 49 | 0 | 9 | 21 | ||||||

| Solid-phase radioimmunoassay inhibition serotyping with rabbit polyclonal antisera (34) | Germany | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Africa | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Brazil | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| North America | 2 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | North America | 1 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 2 | |

| Ouchterlony immunodiffusion with rabbit polyclonal antisera and/or whole-cell ELISA with a panel of 14 MAbs (24, 26) | Various | 5 | 11 | 1 | 9 | 0 | Various | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Total | 179 | 199 | 75 | 2 | 17 | 26 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Percentage of total | 35.9 | 40.0 | 15.1 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 27.3 | 50.0 | 9.1 | 9.1 | ||

MAbs, monoclonal antibodies; ND, not determined.

rSBA. (i) Natural immunity.

The development of natural immunity over time was assessed in control subjects, i.e., those who had not received a MenA conjugate vaccine. In infants (studies A and B) and in toddlers (studies C and E), the percentages of seropositive samples (i.e., titers of ≥1:8) from control subjects aged 10 months and above were substantially lower with the L10-rSBA than with the L11-rSBA (Table 3). Natural immunity also was assessed in prevaccination samples. As with the infants and toddlers, in older children 3 to 5 years of age and in adolescents (studies D and E), the percentages of seropositive samples was approximately 40 to 60% lower with the L10-rSBA than with the L11-rSBA.

Table 3.

Seroprotection rates and GMTs for SBA-MenA using rabbit complement and the L10 or L11 immunotype in five studies of infants, toddlers, and adolescentsa

| Study group and immunotype | Vaccination group | Time point (age) | N | Seropositivity rate (% with titer of ≥1:8) (95% CI) | GMT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study A, Philippines (infants) | |||||

| L11 | Hib-MenAC | PIII (4–5 mo) | 38 | 97.4 (86.2; 99.9) | 360.6 (252.6; 514.7) |

| 10 mo | 39 | 92.3 (79.1; 98.4) | 164.6 (99.7; 271.7) | ||

| Control | PIII (4–5 mo) | 35 | 8.6 (1.8; 23.1) | 6.1 (3.8; 10.0) | |

| 10 mo | 36 | 69.4 (51.9; 83.7) | 84.1 (40.6; 174.3) | ||

| L10 | Hib-MenAC | PIII (4–5 mo) | 13 | 100 (75.3; 100) | 248.5 (97.9; 631.1) |

| 10 mo | 38 | 81.6 (65.7; 92.3) | 75.2 (40.0; 141.4) | ||

| Control | PIII (4–5 mo) | ND | ND | ||

| 10 mo | 29 | 10.3 (2.2; 27.4) | 4.7 (3.7; 5.9) | ||

| Study B, Ghanac (infants) | |||||

| L11 | Hib-MenAC | PIII (4–5 mo) | 89 | 88.8 (80.3; 94.5) | 67.6 (50.3; 90.8) |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 97 | 48.5 (38.2; 58.8) | 28.1 (18.1; 43.6) | ||

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 94 | 94.7 (88.0; 98.3) | 418.6 (297.8; 588.3) | ||

| Control | PIII (4–5 mo) | 114 | 8.8 (4.3; 15.5) | 5.4 (4.4; 6.7) | |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 96 | 27.1 (18.5; 37.1) | 13.3 (8.7; 20.1) | ||

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 101 | 52.5 (42.3; 62.5) | 50.5 (30.6; 83.3) | ||

| L10 | Hib-MenAC | PIII (4–5 mo) | 70 | 91.4 (82.3; 96.8) | 79.4 (56.5; 111.7) |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 61 | 39.3 (27.1; 52.7) | 11.0 (7.5; 16.0) | ||

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 74 | 94.6 (86.7; 98.5) | 360.6 (233.5; 556.8) | ||

| Control | PIII (4–5 mo) | 70 | 7.1 (2.4; 15.9) | 4.9 (4.0; 5.9) | |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 56 | 8.9 (3.0; 19.6) | 5.4 (4.1; 7.0) | ||

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 63 | 22.2 (12.7; 34.5) | 9.5 (6.1; 14.7) | ||

| Study C, Thailand (toddlers) | |||||

| L11b | Hib-MenAC | Pre (15–24 mo) | 226 | 99.6 (97.6; 100) | 626.2 (551.6; 711.0) |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 136 | 100 (97.3; 100) | 1,488.8 (1,318.7; 1,680.8) | ||

| Control | Pre (15–24 mo) | 70 | 88.6 (78.7; 94.9) | 327.2 (215.4; 497.0) | |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 74 | 100 (95.1; 100) | 3,429.6 (2,939.5; 4,001.4) | ||

| L10 | Hib-MenAC | Pre (15–24 mo) | 224 | 88.8 (84.0; 92.6) | 141.1 (115.1; 172.9) |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 224 | 100 (98.4; 100) | 1,784.8 (1,611.2; 1,977.1) | ||

| Control | Pre (15–24 mo) | 59 | 54.2 (40.8; 67.3) | 37.1 (21.3; 64.7) | |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 73 | 100 (95.1; 100) | 1,663.7 (1,415.4; 1,955.6) | ||

| Study D, Denmark (adolescents) | |||||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 23 | 100 (85.2; 100) | 890.7 (711.9; 1,114.4) |

| Post-D1 | 24 | 100 (85.8; 100) | 9,264.0 (6,342.3; 13,531.7) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 23 | 95.7 (78.1; 99.9) | 680.1 (381.8; 1,211.3) | |

| Post-D1 | 25 | 100 (86.3; 100) | 8,283.6 (6,034.9; 11,370.3) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 22 | 63.6 (40.7; 82.8) | 52.8 (20.8; 134.5) |

| Post-D1 | 24 | 100 (85.8; 100) | 4,672.2 (3,271.6; 6,672.6) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 20 | 50.0 (27.2; 72.8) | 36.3 (12.3; 107.5) | |

| Post-D1 | 25 | 100 (86.3; 100) | 3,254.2 (2,042.1; 5,185.7) | ||

| Study E, Germany and Austria (toddlers and older children) | |||||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 37 | 51.4 (34.4; 68.1) | 44.1 (19.5; 99.6) |

| Post-D1 | 42 | 100 (91.6; 100) | 5,665.2 (4,086.0; 7,854.9) | ||

| MenC-CRM | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 37 | 18.9 (8.0; 35.2) | 9.1 (5.1; 16.3) | |

| Post-D1 | 39 | 35.9 (21.2; 52.8) | 20.5 (9.7; 43.3) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 38 | 15.8 (6.0; 31.3) | 8.2 (4.7; 14.2) |

| Post-D1 | 42 | 100 (91.6; 100) | 2,926.9 (2,014.7; 4,252.2) | ||

| MenC-CRM | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 44 | 2.3 (0.1; 12.0) | 4.1 (3.9; 4.4) | |

| Post-D1 | 45 | 2.2 (0.1; 11.8) | 4.6 (3.5; 6.2) | ||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 40 | 80.0 (64.4; 90.9) | 192.8 (100.1; 371.4) |

| Post-D1 | 49 | 100 (92.7; 100) | 8,299.4 (6,734.2; 10,228.4) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 31 | 71.0 (52.0; 85.8) | 139.0 (56.7; 341.1) | |

| Post-D1 | 33 | 100 (89.4; 100) | 3,798.4 (2,888.9; 4,994.2) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 43 | 20.9 (10.0; 36.0) | 10.2 (5.7; 18.3) |

| Post-D1 | 49 | 100 (92.7; 100) | 4,262.9 (3,389.0; 5,362.2) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 27 | 33.3 (16.5; 54.0) | 19.4 (7.7; 48.8) | |

| Post-D1 | 33 | 100 (89.4; 100) | 1,727.7 (1,271.1; 2,348.3) |

PS, one-fifth dose of polysaccharide vaccine Mencevax AC; Hib-MenAC, priming with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC vaccine; ACWY-TT/PS, ACWY conjugate/polysaccharide vaccine; control, priming with three doses of either DTPw-HBV + Hib or DTPw-HBV/Hib vaccine; PIII, 1 month after primary vaccination; Pre, prior to booster vaccination; Post-PS/Post Hib-MenAC, 1 month after polysaccharide booster or DTPw-HBV-Hib/MenAC conjugate vaccine booster; Pre-D1/Post-D1, predose and 1 month after a single dose of the vaccine indicated; ND, no data. CI, confidence interval.

The differences in the numbers of the pre- and postvaccination Hib-MenAC cohort are due to a high proportion of invalid results after booster administration.

Subset of subjects with results for each assay available at each time point.

(ii) Response after primary (three-dose or one-dose) vaccination.

In vaccinated infants and toddlers (studies A, B, C, and E), the percentages of seropositive samples 1 month after three doses (studies A and B) or 1 month after one dose (studies C and E) were within the same range for both the L10-rSBA and L11-rSBA (Table 3). Thus, since a high level of natural immunity prior to vaccination was detected by the L11-rSBA, the use of the L10-rSBA in these populations allowed a better detection of vaccine-induced immunity.

In toddlers between 15 and 24 months of age primed with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC vaccine (study C), the percentage of subjects with persisting rSBA-MenA titers of ≥1:8 was somewhat lower with the L10-rSBA than with the L11-rSBA (88.8 and 99.6%, respectively), but the differences between unvaccinated and vaccinated subjects were larger with the L10-rSBA than with the L11-rSBA (for the Pre group [prior to booster vaccination; 15- to 24-month time point], the L10-rSBA result was 54.2% in unvaccinated versus 88.8% in vaccinated subjects; for L11-rSBA, the result was 88.6% in unvaccinated versus 99.6% in vaccinated subjects). The same pattern was observed at persistence time points of studies A and B (10 and 12 months, respectively) (Table 3).

In adolescents and children more than 2 years of age vaccinated with MenA conjugate or ACWY polysaccharide vaccine (studies D and E), the postvaccination geometric mean titers (GMTs) were lower with the L10-rSBA than with the L11-rSBA. However, the percentages of seropositive samples postvaccination were 100% with both assays (Tables 3). Moreover, in each age group, the vaccine response rates were similar using either the L11-rSBA or the L10-rSBA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Vaccine response rates for SBA-MenA using rabbit and human complement in studies D and E for the L10 or L11 immunotype

| Complement source | Study groupa | Vaccine response for immunotypeb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L11 |

L10 |

||||

| n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | ||

| Study D, Denmark (adolescents) | |||||

| Rabbit | ACWY-TT | 23 | 87.0 (66.4; 97.2) | 22 | 90.9 (70.8; 98.9) |

| ACWY-PS | 23 | 78.3 (56.3; 92.5) | 20 | 95.0 (75.1; 99.9) | |

| Human | ACWY-TT | 16 | 75.0 (47.6; 92.7) | 23 | 78.3 (56.3; 92.5) |

| ACWY-PS | 15 | 40.0 (16.3; 67.7) | 23 | 47.8 (26.8; 69.4) | |

| Study E, Germany and Austria (children 3–5 yr) | |||||

| Rabbit | ACWY-TT | 40 | 92.5 (79.6; 98.4) | 43 | 97.7 (87.7; 99.9) |

| ACWY-PS | 31 | 80.6 (62.5; 92.5) | 26 | 88.5 (69.8; 97.6) | |

| Human | ACWY-TT | 25 | 76.0 (54.9; 90.6) | 37 | 67.6 (50.2; 82.0) |

| ACWY-PS | 24 | 25.0 (9.8; 46.7) | 24 | 16.7 (4.7; 37.4) | |

ACWY-TT/PS, ACWY conjugate/polysaccharide vaccine.

Vaccine responses were defined as a postvaccination titer of ≥32 (rSBA) or ≥8 (hSBA) for subjects who initially were seronegative (<8 for rSBA and <4 for hSBA) and a ≥4-fold increase before and after vaccination for subjects who initially were seropositive (rSBA and hSBA).

(iii) Postbooster responses and technical limitations of the L11-rSBA.

Unexpectedly, the L11-rSBA GMT was lower in toddlers who had received a three-dose primary vaccination and booster with DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC conjugate vaccine (study C) than in unprimed toddlers vaccinated with a single dose of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC in the second year of life (1,488.8 versus 3,429.6, with the 95% CIs not overlapping) (Table 3). In contrast, the postbooster meningococcal anti-PSA IgG GMC, as measured by ELISA, was higher in the primed and boosted toddlers than in unprimed toddlers (20.31 versus 14.2 μg/ml, with 95% CIs not overlapping) (Table 5). We also noted that 40% of the postvaccination samples in study C, primarily sera from subjects who had received four doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC, gave invalid results (i.e., killing without the addition of complement) with the L11-rSBA (data not shown). With the L10-rSBA, all sera were successfully tested, and differences in GMTs between vaccination schedules were not apparent (postvaccination GMTs, 1,784.8 versus 1,663.7 after four doses of Hib-MenAC versus one dose of Hib-MenAC, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 5.

Seropositivity rates and GMCs for anti-PSA antibodies in five studies of infants, toddlers, older children, and adolescentsa

| Study group | Time point (age) | n | % Samples with titer of ≥0.3 μg/ml (95% CI) | % Samples with titer of ≥2.0 μg/ml (95% CI) | GMC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study A, Philippines (infants) | |||||

| Hib-MenAC | PIII (4.5 mo) | 44 | 100 (92.0; 100) | 100 (92.0; 100) | 18.25 (14.24; 23.40) |

| 10 mo | 44 | 93.2 (81.3; 98.6) | 50.0 (34.6; 65.4) | 1.78 (1.24; 2.55) | |

| Control | PIII (4.5 mo) | 40 | 0.0 (0.0; 8.8) | 0.0 (0.0; 8.8) | 0.15 (0.15; 0.15) |

| 10 mo | 42 | 4.8 (0.6; 16.2) | 0.0 (0.0; 8.4) | 0.16 (0.15; 0.17) | |

| Study B, Ghana (infants) | |||||

| Hib-MenAC | PIII (4.5 mo) | 115 | 100 (96.8; 100) | 93.9 (87.9; 97.5) | 6.40 (5.52; 7.43) |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 115 | 23.5 (16.1; 32.3) | 0.9 (0.0; 4.7) | 0.21 (0.19; 0.24) | |

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 120 | 90.8 (84.2; 95.3) | 70.0 (61.0; 78.0) | 4.72 (3.41; 6.52) | |

| Control | PIII (4.5 mo) | 120 | 25.8 (18.3; 34.6) | 6.7 (2.9; 12.7) | 0.24 (0.20; 0.29) |

| Pre-PS (12 mo) | 115 | 5.2 (1.9; 11.0) | 0.0 (0.0; 3.2) | 0.16 (0.15; 0.17) | |

| Post-PS (13 mo) | 117 | 47.0 (37.7; 56.5) | 12.8 (7.4; 20.3) | 0.38 (0.30; 0.48) | |

| Study C Thailand, (toddlers) | |||||

| Hib-MenAC | Pre (15–24 mo) | 246 | 78.9 (73.2; 83.8) | 12.6 (8.7; 17.4) | 0.64 (0.57; 0.72) |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 246 | 100 (95.8; 100) | 97.6 (94.8; 99.1) | 20.31 (17.92; 23.01) | |

| Control | Pre (15–24 mo) | 76 | 18.4 (10.5; 29.0) | 2.6 (0.3; 9.2) | 0.20 (0.17; 0.23) |

| Post Hib-MenAC | 76 | 100 (95.3; 100) | 100 (95.3; 100) | 14.20 (11.95; 16.88) | |

| Study D, Denmark (adolescents) | |||||

| ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 23 | 60.9 (38.5; 80.3) | 17.4 (5.0; 38.8) | 0.62 (0.32; 1.21) |

| Post-D1 | 24 | 100 (85.8; 100) | 100 (85.8; 100) | 27.26 (18.50; 40.16) | |

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 23 | 56.5 (34.5; 76.8) | 4.3 (0.1; 21.9) | 0.36 (0.24; 0.55) |

| Post-D1 | 25 | 100 (86.3; 100) | 88.0 (68.8; 97.5) | 12.93 (7.20; 23.22) | |

| Study E, Germany and Austria (toddlers and older children) | |||||

| ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 37 | 5.4 (0.7; 18.2) | 0.0 (0.0; 9.5) | 0.16 (0.14; 0.18) |

| Post-D1 | 43 | 100 (91.8; 100) | 100 (91.8; 100) | 37.27 (29.31; 47.40) | |

| MenC-CRM | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 43 | 4.7 (0.6; 15.8) | 0.0 (0.0; 8.2) | 0.16 (0.14; 0.18) |

| Post-D1 | 43 | 7.0 (1.5; 19.1) | 2.3 (0.1; 12.3) | 0.17 (0.14; 0.20) | |

| ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 46 | 13.0 (4.9; 26.3) | 4.3 (0.5; 14.8) | 0.19 (0.16; 0.24) |

| Post-D1 | 49 | 100 (92.7; 100) | 100 (92.7; 100) | 29.25 (22.57; 37.90) | |

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 30 | 16.7 (5.6; 34.7) | 3.3 (0.1; 17.2) | 0.20 (0.14; 0.30) |

| Post-D1 | 34 | 100 (89.7; 100) | 94.1 (80.3; 99.3) | 11.43 (7.73; 16.89) |

PS, one-fifth dose of polysaccharide vaccine Mencevax AC; Hib-MenAC, priming with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC vaccine; ACWY-TT/PS, ACWY conjugate/polysaccharide vaccine; MenC-CRM, Meningitec; control, priming with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib vaccine; PIII, 1 month after primary vaccination; Pre, prior to booster vaccination; Post-PS/booster, 1 month post polysaccharide booster or DTPw-HBV-Hib/MenAC conjugate vaccine booster; Pre-D1/Post-D1, predose and 1 month after a single dose of the vaccine indicated; CI, confidence interval.

(iv) hSBA.

Using hSBA with either the L10 or L11 immunotype, there was a reduction in the percentage of seroprotective samples (hSBA titer, ≥1:4) and a major reduction in SBA GMTs prior to and after vaccination compared to the rSBA seropositivity rates and GMTs. This was apparent in the three age strata for which hSBA results were available, i.e., toddlers, children 3 to 5 years of age, and adolescents (Table 6).

Table 6.

Seroprotection rates and GMTs for SBA-MenA using human complement and L10 or L11 in studies C to Ea

| Immunotype | Study group | Time point (age) | n | Seroprotection rate (% with titer of ≥1:4) (95% CI) | GMT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study C Thailandb (toddlers) | |||||

| L10 | Hib-MenAC | Pre (15–24 mo) | 199 | 41.2 (34.3; 48.4) | 7.0 (5; 9) |

| Postbooster | 191 | 97.4 (94.0; 99.1) | 943 (744; 1196) | ||

| Control | Pre (15–24 mo) | 56 | 21.4 (11.6; 34.4) | 3.0 (2; 3) | |

| Post booster | 70 | 64.3 (51.9; 75.4) | 10 (7; 14) | ||

| Study D Denmark (adolescents) | |||||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 20 | 20.0 (5.7; 43.7) | 2.7 (2.0; 3.7) |

| Post-D1 | 20 | 85.0 (62.1; 96.8) | 55.5 (22.6; 136.2) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 18 | 5.6 (0.1; 27.3) | 2.2 (1.8; 2.8) | |

| Post-D1 | 19 | 47.4 (24.4; 71.1) | 9.0 (3.8; 21.4) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 24 | 58.3 (36.6; 77.9) | 5.0 (3.5; 7.4) |

| Post-D1 | 23 | 87.0 (66.4; 97.2) | 45.2 (22.2; 91.8) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (15–19 yr) | 24 | 45.8 (25.6; 67.2) | 3.5 (2.7; 4.6) | |

| Post-D1 | 23 | 65.2 (42.7; 83.6) | 12.5 (6.4; 24.3) | ||

| Study E Germany and Austria (toddlers and children) | |||||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 30 | 0.0 (0.0; 11.6) | 2.0 (2.0; 2.0) |

| Post-D1 | 26 | 96.2 (80.4; 99.9) | 52.5 (33.2; 83.0) | ||

| MenC-CRM | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 34 | 2.9 (0.1; 15.3) | 2.1 (1.9; 2.2) | |

| Post-D1 | 34 | 2.9 (0.1; 15.3) | 2.1 (1.9; 2.2) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 36 | 5.6 (0.7; 18.7) | 2.1 (1.9; 2.4) |

| Post-D1 | 28 | 92.9 (76.5; 99.1) | 39.8 (24.6; 64.4) | ||

| MenC-CRM | Pre-D1 (12–14 mo) | 42 | 7.1 (1.5; 19.5) | 2.1 (2.0; 2.3) | |

| Post-D1 | 32 | 12.5 (3.5; 29.0) | 2.6 (2.0; 3.6) | ||

| L11 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 38 | 0.0 (0.0; 9.3) | 2.0 (2.0; 2.0) |

| Post-D1 | 30 | 80.0 (61.4; 92.3) | 28.7 (15.5; 53.3) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 27 | 0.0 (0.0; 12.8) | 2.0 (2.0; 2.0) | |

| Post-D1 | 27 | 25.9 (11.1; 46.3) | 3.5 (2.2; 5.5) | ||

| L10 | ACWY-TT | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 38 | 15.8 (6.0; 31.3) | 2.7 (2.1; 3.4) |

| Post-D1 | 42 | 83.3 (68.6; 93.0) | 23.7 (14.8; 38.1) | ||

| ACWY-PS | Pre-D1 (3–5 yr) | 29 | 13.8 (3.9; 31.7) | 3.2 (2.0; 5.0) | |

| Post-D1 | 26 | 42.3 (23.4; 63.1) | 5.9 (3.2; 11.0) |

Hib-MenAC, priming with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC vaccine; ACWY-TT/PS, ACWY conjugate/polysaccharide vaccine; control, priming with three doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib vaccine; Pre, prior to booster vaccination; Postbooster, 1 month after DTPw-HBV-Hib/MenAC conjugate vaccine booster; Pre-D1/Post-D1, predose and 1 month after a single dose of the vaccine indicated; CI, confidence interval.

No L11 assay was conducted for this cohort.

Natural immunity. (i) Natural immunity in prevaccination samples.

In contrast to the comparisons observed with the L10- and L11-rSBAs, there was a slightly higher percentage of seroprotective samples (titers, ≥1:4) with the L10-hSBA than with the L11-hSBA. The differences between the two assays appeared to increase with the age of the subjects examined (Table 6).

(ii) Primed or unprimed toddlers.

In the toddlers of study C and using L10-hSBA, there was a dramatic difference in the measurement of immunogenicity after one vaccine dose (64.3% seroprotected; GMT = 10) compared to that of four vaccine doses (97.4% seroprotected; GMT = 943). This difference was not apparent with either the L11-rSBA or the L10-rSBA (Tables 3 and 6). Using the L10-hSBA, there was also a substantially higher GMT following four doses of DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC than with a single dose in the second year of life. L11-hSBA was not performed with this cohort.

In adolescents vaccinated with ACWY-PS and using the L10-hSBA, 65.2% of samples were seroprotective (titers, ≥1:4), whereas 47.4% of samples were seroprotective using the L11-hSBA (Table 6). Vaccine response rates in adolescents and children 3 to 5 years old were within the same range using either the L10-hSBA or L11-hSBA. However, these vaccine response rates generally were lower than those observed with rSBA using L10 or L11 strains (Table 4).

Both hSBAs used on samples from young children and adolescents allowed a better discrimination between conjugate and polysaccharide responses than the corresponding rSBAs. This was reflected by both the vaccine response rates (Table 4) and the seroprotection rates (Tables 3 and 6). In study E, more than 90% of samples from toddlers and 80% of samples from children 3 to 5 years old and vaccinated with ACWY-TT were seroprotective, using either L10-hSBA or L11hSBA, 1 month after vaccination (Table 6). The seroprotective rates were only 42.3% (L10-hSBA) and 25.9% (L11hSBA) for 3- to 5-year-old subjects vaccinated with the ACWY-PS vaccine (Table 6). When assessed using the rSBA, all samples from these subjects were seropositive (titers, ≥1:8) (Table 3).

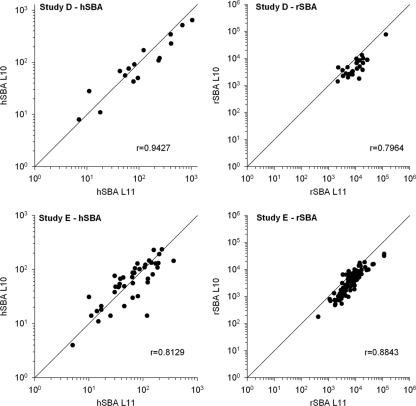

(iii) Correlation between results obtained with the L10 and L11 assays.

The correlation between postvaccination results using the L11- and L10-SBAs with either human or rabbit complement in studies D and E is given in Fig. 2. For both studies, the correlation (r) and the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) of the L10-hSBA and L11-hSBA were high, around the putative level for protection (titer, ≥1:4) for both studies. Values for r and CCC were 0.9427 and 0.9256, respectively, for study D and 0.8129 and 0.8108, respectively, for study E. Values of r and CCC also were high for the rSBA (titer, ≥1:8), reaching r = 0.7964 and CCC = 0.6012 for study D and r = 0.8843 and CCC = 0.7080 for study E.

Fig. 2.

Scatter graphs of the correlation (r) between SBA titers measured with the 3125 strain (L10) and F8238 strain (L11) as targets in studies D and E. Study D, left panel, L10-hSBA versus L11-hSBA (n = 16); right panel, L10-rSBA versus L11-rSBA (n = 24). Study E, left panel, L10-hSBA versus L11-hSBA (n = 43); right panel, L10-rSBA versus L11-rSBA (n = 92). Bisector lines (x = y) are shown in each panel.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that MenA strain 3125 belongs to the L10 immunotype, and that the F8238 MenA strain predominantly expresses the L11 immunotype. This is contrary to previous findings indicating that F8238 expresses predominantly L10 epitopes (20). Although the genotype of some MenA strains allows the simultaneous expression of both L11 and L10 epitopes (22), the absence of an lgtB gene correlates with the L11-only immunotype. In our study, PCR analysis of strain F8238 DNA failed to detect an lgtB gene (data not shown), supporting our biochemical observations that this strain has the L11-only immunotype.

We observed high levels of SBA natural immunity early in life against the F8238 MenA strain. Evidence of natural immunity was largely absent in the first weeks of life (data not shown) but increased over time. We consider IgG unlikely to be important in this regard, in view of the absence of significant maternal antibodies and the very low levels of anti-PSA positivity (<20%) observed in all three studies of toddlers aged 10 to 24 months. Such high levels of natural immunity suggest the rapid induction of IgM antibodies against strain F8238 early in life. These antibodies could be induced by surface antigens of N. meningitidis or other cross-reacting bacteria. A review of the literature found a higher incidence of the L11 immunotype in MenA carriage strains than with disease strains and suggests that LOS immunotypes were responsible, at least in part, for the development of the anti-MenA natural immunity in toddlers and adolescents. This hypothesis is supported by similar observations made previously for MenB, where the recognition of the LOS molecules was shown to potentially influence the outcomes of SBAs depending on the immunotype (21).

MenA case isolates express either L(3,7)9 or L10 epitopes as LOS immunotypes. The natural immunity to MenA may begin early in life by the recognition of epitopes on carrier isolates that are primarily of the L11 LOS immunotype. Natural immunity may originate from the development of an immune response to outer membrane proteins, to noncapsular polysaccharide antigens, to natural exposure to LOS, and possibly to the development of low-avidity antibodies against capsular polysaccharide antigens. Natural immunity to strains belonging to L(3,7)9 or L10 immunotypes would be expected to occur less frequently, given the association of these immunotypes with invasive disease.

After infancy, when exposure to carrier strains of N. meningitidis expressing the L11 immunotype has begun, rabbit SBAs using the F8238 strain are unable to clearly differentiate between pre- and postvaccination responses (i.e., percentage above cutoff) in subjects given MenA capsule-based vaccines. A vaccine effect was shown, however, in terms of an increase in antibody titers. In contrast, our study has demonstrated that the use of a MenA L10 immunotype (strain 3125) in the rabbit SBA significantly reduced the percentage of samples with natural immunity compared to the percentage with the currently recommended F8238 assay strain. Another laboratory also has observed a reduced natural immunity against strain 3125 compared to that of strain F8238 in a study investigating MenA rSBA responses in sera from nonvaccinated Burkina-Faso subjects (30 and Caroline Trotter, personal communication). Importantly, and in our study, the percentage of samples showing a vaccine response remained unaffected when using the L10-rSBA, allowing a higher degree of differentiation between responses in vaccinated and unvaccinated groups than when using the L11-rSBA (i.e., using the F8238 strain).

We hypothesize that anti-L11 natural immunity is unlikely to be protective against invasive strains of the L10 immunotype, implying that the SBA results obtained with an L11 immunotype are misleading. The use of the 3125 strain avoids the measurement of L11-specific natural immunity and focuses on the probably more clinically relevant immunity to L10 strains. Consequently, the L10-based SBA is likely to better reflect differences in protection and susceptibility between vaccinated and unvaccinated subjects.

Finally, the rSBA using the F8238 strain was subject to technical constraints that were not apparent with the 3125 strain, as reflected by the high proportion of invalid results observed in study C, which probably were due to cellular toxicity resulting from high concentrations of bactericidal antibodies in postbooster samples.

In 1969, Goldschneider et al. showed that the incidence of disease was reciprocally related to the serum bactericidal activity to meningococci of serogroups A to C when human complement was used (8). Therefore, we also assessed the performance of the L10 immunotype in hSBA. As previously observed with meningococcal serogroup C (4), we found lower titers in all studies and at all time points with hSBA than with rSBA. Importantly, the L10-hSBA was shown to be equally effective in differentiating between vaccinated and unvaccinated subjects as the L10-rSBA. We demonstrated that the human complement-based L10 assay was able to differentiate between samples from primed and unprimed toddlers in terms of their booster response when given a MenA conjugate vaccine at 15 to 24 months of age, whereas the L10-rSBA was unable to differentiate between these groups.

We evaluated immunogenicity pre- and postvaccination in adolescents given a MenA conjugate vaccine or an unconjugated polysaccharide control vaccine for which vaccine efficacy has been fully demonstrated (2, 7, 29). Increases in seropositivity/seroprotection rates after vaccination with polysaccharide vaccine were detected with either of the L10-SBAs and with the L11-hSBA. Due to the detection of a high level of prevaccination antibodies, such increases in seropositivity rates were not observed with the L11-rSBA. High vaccine response rates and substantial increases in GMTs also were demonstrated using the L10-SBAs after vaccination with polysaccharide vaccine. Similar responses were observed after vaccination with the experimental conjugate vaccine, showing that the L10-SBA is valid for the assessment of the immune response to both polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines.

Using the L10-hSBA, the percentage of seroprotected samples in nonvaccinated subjects was higher than that using L10-rSBA, especially in samples from older populations. There are at least two hypotheses to explain this observation that deserve further assessment. First, it has been described that human complement is less efficiently activated by IgM than rabbit complement (19, 35). Since natural immunity related to LOS probably is related to IgM antibodies, the use of human instead of rabbit complement will yield results that are less influenced by the LOS type expressed by the SBA strain. Second, the different expression of the factor H binding protein (fHbp) by the F8238 and 3125 strains may play a role. FHbp binds human (and not rabbit) complement regulatory factor H, and therefore different expression levels of fHbp may influence the hSBA activity (9).

Our data showed that, using the L10-hSBA, only 65.2% of adolescents vaccinated with the polysaccharide vaccine were seroprotected (hSBA titer, ≥1:4), and this percentage was lower (47.4%) using the L11-hSBA. Results from other studies using L11-hSBAs show similarly low rates of seroprotection in ACWY-PS-vaccinated individuals: after a dose of ACWY-PS vaccine (Menomune; Sanofi Pasteur), only 45% of 2 to 10 year olds (3) and 46% of 11 to 17 year olds achieved titers of ≥1:4 (13), while only 55% of 4 to 10 year olds achieved titers of ≥1:8 (26). These values are lower than the 78 to 94% reported efficacy of the polysaccharide vaccine against meningococcal serogroup A disease (2, 7, 29), suggesting that our hSBAs, along with those of others, lacks sensitivity. Additionally, only 67% of 11- to 18-year-old adolescents vaccinated with the licensed ACWY-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine (Menactra; Sanofi Pasteur) showed hSBA titers of ≥1:8 (12). Thus, lower-than-expected seroprotection rates after vaccination with both conjugate and polysaccharide vaccines from several manufacturers suggest that the sensitivity of the L11-based hSBA is low in general.

One limitation of our analysis is that we have not performed formal statistical comparisons for each of the studies between the data from the L11- and the L10-based assays. Between-assay comparisons were descriptive only, because in some studies the L10-based assay and the hSBA were performed post hoc on a subset of remaining serum samples. However, in each of the five studies, which were conducted in different settings and with different conjugate vaccines, there was a consistent trend for a lower detection of natural immunity using the 3125 strain in the rabbit assay, hence allowing a better discrimination of immunized and nonimmunized subjects. After plain polysaccharide vaccination, the hSBA seroprotection rates also were consistently slightly higher with the 3125 strain across the two studies in which the two assays were performed.

Conclusions.

The use of MenA strain 3125 (L10 immunotype) in rSBA may avoid the measurement of high levels of carriage-strain-induced natural immunity which otherwise is observed with the F8238 strain (L11 immunotype). Taking into account the probably higher clinical relevance of the L10 immunotype, the use of this immunotype target strain in a rabbit complement assay may also better reflect the protection/susceptibility of immunized and nonimmunized subjects.

The human complement SBA demonstrates a lower sensitivity, and this is more pronounced when using the L11 strain. In addition, L11-hSBA data from adolescents immunized with plain polysaccharide are not fully aligned with known MenA polysaccharide vaccine efficacy. Although L10-hSBA data better align with the expected polysaccharide vaccine efficacy, this assay may still lack some sensitivity. The use of hSBA may help differentiate between primary and booster responses to conjugate vaccines in toddlers.

It remains to be evaluated whether or not the findings with the MenA 3125 strain are strain specific or can be extrapolated to other type L10 MenA strains. Moreover, it is well known that components other than LOS, such as the size of the capsules or the presence/abundance of outer membrane proteins interacting with the complement system (reviewed in reference 27), also are involved in the resistance of the bacterial strains to complement. These components may, alone or in conjunction with LOS, affect the complement sensitivity of MenA stain 3125 or F8238 in SBA, and further research is needed to determine the individual role of those other components or LOS. However, our data demonstrated that the MenA strain 3125 (L10) offers advantages over MenA strain F8238 (L11) in SBA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All clinical studies were funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals.

All authors are employees of GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals.

We thank Joanne Wolter and Ulrike Krause for assistance in manuscript preparation. We are grateful to Emil C. Gotschlich (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for providing the A1 strain, the CDC for providing the F8238 strain, and C. T. P. Hopman (University of Amsterdam, Department of Medical Microbiology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for providing the L10 MenA strains and performing the immunoprecipitation assays. We further thank Michel Plisnier for the analysis of LOS by mass spectrometry and Dominique Wauters and Isabelle Lechevin for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Achtman M., et al. 1992. A comparison of the variable antigens expressed by clone IV-1 and subgroup III of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A. J. Infect. Dis. 165:53–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anonymous. 1990. Meningococcal meningitis in the Northern Territory 1990. Commun. Dis. Intell. 18:12–15 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Black S., Dull P. M. 2008. MenACWY-CRM, a novel quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine, is well tolerated and immunogenic in infancy through adolescence [abstract]. In 26th Annu. Meet. European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, (ESPID), 13 to 17 May 2008, Graz, Austria [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borrow R., Andrews N., Goldblatt D., Miller E. 2001. Serological basis for use of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines in the United Kingdom: reevaluation of correlates of protection. Infect. Immun. 69:1568–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gatchalian S., et al. 2008. The development of a new heptavalent diphtheria-tetanus-whole cell pertussis-hepatitis B-Haemophilus influenzae type b-Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A and C vaccine: a randomized dose-ranging trial of the conjugate vaccine components. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 12:278–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gheesling L. L., et al. 1994. Multicenter comparison of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C anti-capsular polysaccharide antibody levels measured by a standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1475–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenwood B. M., et al. 1986. The efficacy of meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine in preventing group A meningococcal disease in The Gambia, West Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80:1006–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldschneider I., Gotschlich E. C., Artenstein M. S. 1969. Human immunity to the meningococcus. I. The role of humoral antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 129:1307–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Granoff D. M., Welsch J. A., Ram S. 2009. Binding of complement factor H (fH) to Neisseria meningitidis is specific for human fH and inhibits complement activation by rat and rabbit sera. Infect. Immun. 77:764–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hitchcock P. J., Brown T. M. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hodgson A., et al. 2008. A phase II, randomized study on an investigational DTPw-HBV/Hib-MenAC conjugate vaccine administered to infants in Northern Ghana. PLoS One 3:e2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson L. A., et al. 2009. Phase III comparison of an investigational quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine with the licensed meningococcal ACWY conjugate vaccine in adolescents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:e1–e10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jackson L. A., et al. 2009. A randomized trial to determine the tolerability and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent meningococcal glycoconjugate vaccine in healthy adolescents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones D. M., et al. 1992. The lipooligosaccharide immunotype as a virulence determinant in Neisseria meningitidis. Microb. Pathog. 13:219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kerdpanich A., et al. 2008. Primary vaccination with a new heptavalent DTPw-HBV/Hib-Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A and C combined vaccine is well tolerated. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 12:88–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J. J., et al. 1988. Electromorphic characterization and description of conserved epitopes of the lipooligosaccharides of group A Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 56:2631–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knuf M., et al. 2010. A dose-range study assessing immunogenicity and safety of one dose of a new candidate meningococcal serogroups A, C, W-135, Y tetanus toxoid conjugate (MenACWY-TT) vaccine administered in the second year of life and in young children. Vaccine 28:744–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin L. I. 1989. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics 45:255–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mandrell R. E., Azmi F. H., Granoff D. M. 1995. Complement-mediated bactericidal activity of human antibodies to poly alpha 2→8 N-acetylneuraminic acid, the capsular polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1279–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maslanka S. E., et al. 1997. Standardization and a multilaboratory comparison of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A and C serum bactericidal assays. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:156–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moran E. E., Brandt B. L., Zollinger W. D. 1994. Expression of the L8 lipopolysaccharide determinant increases the sensitivity of Neisseria meningitidis to serum bactericidal activity. Infect. Immun. 62:5290–5295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Norheim G., et al. 2006. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis isolates from recent outbreaks in Ethiopia and comparison with those recovered during the epidemic of 1988 to 1989. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Østergaard L., Lebacq E., Poolman J., Maechler G., Boutriau D. 2009. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and persistence of meningococcal A, C, W-135 and Y-tetanus toxoid candidate conjugate (MenACWY-TT) vaccine formulations in adolescents aged 15–25 years. Vaccine 27:161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poolman J. T., Hopman C. T. P., Zanen H. C. 1982. Problems in the definition of meningococcal serotypes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 13:339–348 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salih M. A. M., et al. 1990. Characterization of epidemic and non-epidemic Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strains from Sudan and Sweden. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1711–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sanofi-Pasteur 2007. Menactra meningococcal (groups A, C, Y MCV4 and W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine product information. Sanofi-Pasteur, Lyon, France [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schneider M., Exley C. R. M., Ram S., Sim R. B., Tang C. M. 2007. Interactions between Neisseria meningitidis and the complement system. Trends Microbiol. 15:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scholten R. J. P. M., et al. 1994. Lipo-oligosaccharide immunotyping of Neisseria meningitidis by a whole-cell ELISA with monoclonal antibodies. J. Med. Microbiol. 41:236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soriano-Gabarró M., et al. 2007. Effectiveness of a trivalent serogroup A/C/W135 meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine in Burkina Faso, 2003. Vaccine 25(Suppl. 1):A92–A96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trotter C., et al. 2009. Seroprevalence of serum bactericidal antibodies to Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A in Burkina Faso, abstr. P033. In 10th Eur. Meningococcal Dis. Soc. (EMGM) Meeting; Manchester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsai C. M., Frasch C. E. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vermont C., van den Dobbelsteen G. 2002. Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B: laboratory correlates of protection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 34:89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization 2006. Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of group A meningococcal vaccines. WHO/BS/06.2041. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 34. Zollinger W., Mandrell R. 1980. Type-specific antigens of group A Neisseria meningitidis: lipopolysaccharide and heat-modifiable outer membrane proteins. Infect. Immun. 28:451–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zollinger W. D., Mandrell R. E. 1983. Importance of complement source in bactericidal activity of human antibody and murine monoclonal antibody to meningococcal group B polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 40:257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]