Abstract

Immunization of mice with inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) with concurrent dosing of poliovirus antiviral V-073 showed no detrimental impact on the elicitation of serum-neutralizing antibodies. A strategy involving coadministration of antiviral V-073 and IPV can be considered for the management of poliovirus incidents.

TEXT

The dramatic progress of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) toward its goal is attributed to the use of the oral polio vaccine (OPV), an inexpensive and easily administered live, attenuated vaccine. OPV is generally safe and has been effective under most circumstances. However, at a low frequency, about 1 per 750,000 vaccinees, OPV itself can cause paralysis (vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]) (1). Moreover, with administration of OPV, vaccine virus is excreted in the stool of healthy individuals for several weeks. With continued circulation in the community, vaccine strains accumulate mutations and become virulent vaccine-derived polioviruses (termed cVDPVs) that may cause outbreaks of paralytic disease (4). Additionally, in individuals with immune deficiencies, such as agammaglobulinemia, immunodeficiency-associated vaccine-derived polioviruses (termed iVDPVs) can be excreted for years (3).

While the benefits of OPV outweigh the risk of VDPV-induced disease when wild poliovirus transmission levels are high, as wild poliovirus transmission is eliminated and VAPP and cVDPV cases constitute the sole forms of infection, the risk balance shifts. Consequently, the current GPEI plan is to stop routine OPV use once wild poliovirus transmission has been interrupted globally (7). It is expected that during the first few years after OPV cessation there will be outbreaks of paralytic disease due to the continued circulation of cVDPV. Currently, control of such poliovirus incidents must rely on the use of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), a parenterally administered vaccine. IPV provides excellent individual protection against polio disease. However, IPV does not induce mucosal immunity sufficient to prevent poliovirus replication in the intestinal tract. When most IPV-vaccinated persons are exposed to poliovirus, the virus still multiplies in the intestines and is shed in the stool, which can contribute to continued virus circulation. Further, in the context of emergency prophylaxis, it may take a number of days for the immune response to develop after IPV vaccination, during which time individuals remain unprotected. Thus, IPV alone may be inadequate for management of polio incidents posteradication.

In view of these considerations, it has been recommended that poliovirus antiviral drugs be developed to assist in the management of poliovirus incidents (2, 5). An antiviral drug could act rapidly on its own to treat the infected and protect the exposed and might be particularly useful in conjunction with IPV to control polio outbreaks. The concurrent administration of a fast-acting drug with IPV could provide immediate antiviral protection while long-term immunity develops from vaccination.

To explore whether administration of a poliovirus antiviral drug during vaccination affects vaccine protective efficacy, we assessed the immunogenicity of IPV in mice when it was administered simultaneously with the candidate poliovirus antiviral drug V-073 during either the primary vaccination or the booster immunization. V-073 is a poliovirus-specific capsid inhibitor demonstrated to have potent antiviral activity in vitro against all poliovirus isolates tested to date (6).

Pharmacokinetics of V-073 in mice.

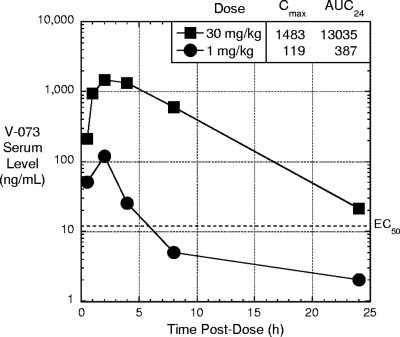

The pharmacokinetics of a low and a high dose of V-073 in mice was investigated to understand the level and duration of drug exposure animals would experience during the immunization experiment. V-073 (ViroDefense, Inc., Rockville, MD) dissolved in corn oil (Sigma- Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered by oral gavage at a dose of either 1 or 30 mg/kg body weight. At various times postdosing, terminal blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture from 3 animals per time point. As seen in Fig. 1, the maximum drug concentration in serum (Cmax) occurred at 2 h postdosing at both dose levels and was followed by a steady clearance of drug. The drug exposure over the 24-h period (area under the curve [AUC24]) was dose proportional. The antiviral activity in cell culture of V-073 against type 1 polioviruses, as measured by the median effective concentration (EC50), is 11 ng/ml (6). Thus, administration of drug at 1 mg/kg represents a suboptimal dose, while a dose of 30 mg/kg exceeds that necessary for mouse efficacy (unpublished data).

Fig. 1.

Pharmacokinetics of V-073 in mice (Cmax, ng/ml; AUC24, ng·h/ml).

Study design.

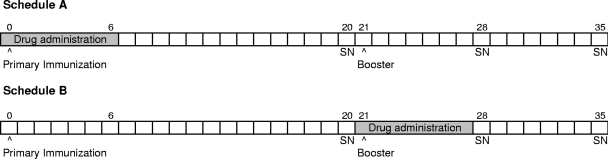

The potential impact of antiviral drug administration during IPV vaccination was investigated according to two drug dosing schedules, each across a range of drug dose levels. In both schedules, vaccination of mice with monovalent type 1 IPV (lot no. FA307685; Aventis) involved a primary IPV immunization on day 0 and a booster on day 21. Vaccine was administered by subcutaneous injection of 3 D-antigen units (DU)/mouse in 0.5 ml. In schedule A, oral V-073 treatment at four drug dose levels (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) was initiated 6 h before administration of the primary parenteral vaccine dose on day 0 and was continued twice daily (q12h) through day 6. One control group received drug vehicle alone according to the same schedule, and a second control group was immunized only (no-treatment group). In schedule B, the drug was administered orally twice daily across the same drug dose levels but on days 21 through 27, during the booster immunization. A similar vehicle control group was included. These schedules are schematically depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schedules of immunization and antiviral treatment.

The effect of antiviral drug administration at the time of either primary or booster immunization was assessed by determination of the levels of serum-neutralizing (SN) antibody elicited against poliovirus using a microneutralization test (8). Sera from blood collected from the tail vein on days 20, 28, and 35 were heat inactivated for 30 min at 56°C, diluted 1:8 in maintenance medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM] supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and 1% of antibiotic/antimycotic [all from Invitrogen]), and sterile filtered through a Spin-X column (Corning, Corning, NY). Twofold serial dilutions of the sera in triplicate, starting at 1:8, were incubated with 100 50% cell culture infective doses (CCID50) of Mahoney type 1 poliovirus in an equal volume for 3 h at 36°C, 5% CO2. At the end of the incubation, 1 × 104 HEp-2C cells were added, and the plates were incubated for 10 days at 36°C, 5% CO2, and read microscopically. Serum-neutralizing (SN) antibody titers were calculated using the Kärber formula (8). Group median and geometric mean titers (GMT) and Student t test P values were calculated using Microsoft Excel software.

Effect of antiviral V-073 administration on the IPV response in mice.

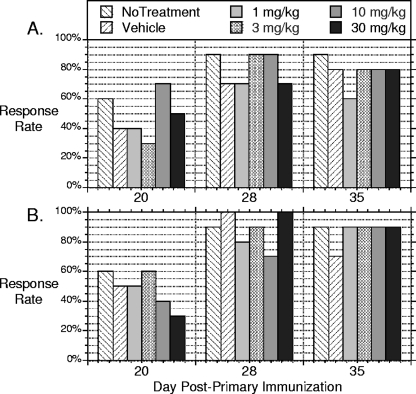

Vaccination response rates, defined as percentage of animals with detectable serum-neutralizing titers (titer of ≥7), for each group treated according to schedules A and B are presented in Fig. 3. For the “no-treatment” group, at day 20, 60% of the animals seroconverted. On day 20 in the schedule A groups (Fig. 3A), response rates ranged from 30% (3 mg/kg) to 70% (10 mg/kg). One week after the booster immunization, the seroconversion rate of all groups rose to between 70% and 90% and was largely maintained through day 35. By Fisher's exact test, there were no significant differences between groups within any time point. There appeared to be little if any effect on the response rate to IPV vaccination when V-073 drug was administered during the primary vaccination. Similar results were observed in the schedule B groups, when V-073 was administered during the booster immunization (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of animals in which serum-neutralizing antibody response was elicited by IPV administered to untreated mice and mice administered vehicle or various doses of V-073 (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) at the time of primary vaccination (A) or booster immunization (B). The response was assessed on days 20 (before booster), 28 (7 days after booster), and 35 (14 days after booster).

Effect of antiviral V-073 administration on the level of SN antibodies elicited by IPV vaccination of mice.

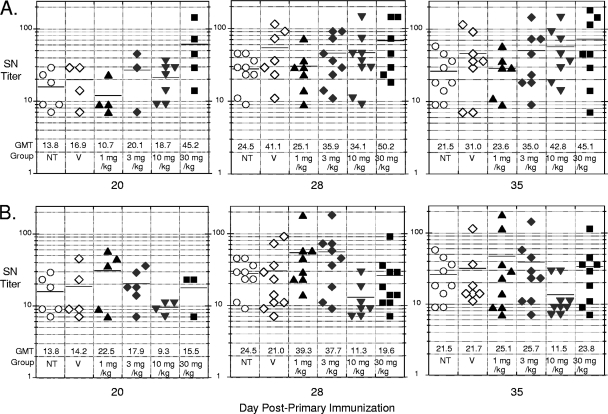

Figure 4 provides the individual, median, and geometric mean SN titers of responding mice for all groups on days 20, 28, and 35. Animals immunized and not treated otherwise (NT) showed GMT values for SN antibodies of 13.8, 24.5, and 21.5 on days 20, 28, and 35, respectively. The GMT values for the schedule A group (Fig. 4A) on day 20 were comparable to that for the no-drug-treated controls, with the possible exception of the 30-mg/kg-dose group, where the value was about 3-fold higher. At day 28, all groups showed SN titer increases of similar magnitude, except for the 30-mg/kg group, whose titer increased only modestly over its already high level on day 20. The day 35 SN titers were largely maintained. For the schedule B groups, the day 20 GMT values were all very similar, as would be expected (no drug treatment at this point). After the booster immunization and 1 week of drug treatment, all drug-treated groups exhibited modest SN titer increases, which were largely maintained on day 35. Student t test indicated that there were no significant differences in neutralization titers in groups of mice immunized in the presence of V-073 according to either schedule A or B compared to those in groups immunized alone.

Fig. 4.

Serum-neutralizing (SN) antibody titers elicited by IPV in untreated mice (NT) and mice administered vehicle (V) or various doses of V-073 (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) at the time of primary vaccination (A) or booster immunization (B). Median titers are indicated by the solid line in each column, and geometric mean titer (GMT) values are provided below for each indicated group.

Based on this preliminary evaluation, there appears to be no detrimental impact on the immunogenicity of IPV in mice when antiviral V-073 is administered during either the primary vaccination or the booster immunization. Therefore, a strategy involving the coadministration of an antiviral drug, such as V-073, and IPV is viable and can be considered for the control of poliovirus incidents.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Interagency Agreement number 224-06-1322/Y1-AI-6153-01 between CBER/FDA and NIAID/NIH. ViroDefense, Inc., received financial support from The Task Force for Global Health, Inc., through grants from the WHO and Rotary International.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Food and Drug Administration.

We thank Walter Dowdle for his continued support.

M.S.C. is a principal in ViroDefense, Inc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 June 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexander L. N., et al. 2004. Vaccine policy changes and epidemiology of poliomyelitis in the United States. JAMA 292:1696–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collett M. S., Neyts J., Modlin J. F. 2008. A case for developing antiviral drugs against polio. Antiviral Res. 79:179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martín J., Dunn G., Hull R., Patel V., Minor P. D. 2000. Evolution of the Sabin strain of type 3 poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient during the entire 637-day period of virus excretion. J. Virol. 74:3001–3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minor P. 2009. Vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV): impact on poliomyelitis eradication. Vaccine 27:2649–2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Science Council 2006. Exploring the role of antiviral drugs in the eradication of polio. Committee on Development of a Polio Antiviral and Its Potential Role in Global Poliomyelitis Eradication, National Research Council. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oberste M. S., et al. 2009. In vitro antiviral activity of V-073 against polioviruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4501–4503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization 2004. Global action plan for laboratory containment of wild polioviruses, 3rd ed. WHO/V&B/03.11. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization 1997. Manual for the virological investigation of polio. WHO/EPI/GEN/97.01. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]