Abstract

A high-resolution amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) methodology was developed to achieve the delineation of closely related Lactococcus lactis strains. The differentiation depth of 24 enzyme-primer-nucleotide combinations was experimentally evaluated to maximize the number of polymorphisms. The resolution depth was confirmed by performing diversity analysis on 82 L. lactis strains, including both closely and distantly related strains with dairy and nondairy origins. Strains clustered into two main genomic lineages of L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris type-strain-like genotypes and a third novel genomic lineage rooted from the L. lactis subsp. lactis genomic lineage. Cluster differentiation was highly correlated with small-subunit rRNA homology and multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) studies. Additionally, the selected enzyme-primer combination generated L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype-specific fragments irrespective of the genotype. These phenotype-specific markers allowed the differentiation of L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype from L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype strains within the same L. lactis subsp. cremoris type-strain-like genomic lineage, illustrating the potential of AFLP for the generation of phenotype-linked genetic markers.

INTRODUCTION

Lactococcus lactis is commonly found in defined and artisan cheese starter cultures as blends of strains with differential functionality during the cheese production process. L. lactis accommodates three subspecies: L. lactis subsp. lactis, L. lactis subsp. cremoris, and L. lactis subsp. hordniae, with the first two having significant economic importance to dairy fermentations. The subspecies differentiation and nomenclature are traditionally based on phenotypes according to the taxonomic reclassification published by Schleifer et al. (20). The so-called L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype is differentiated from the L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype by its growth at 40°C, resistance to 4% salt, and utilization of arginine and maltose (4, 20). L. lactis subsp. lactis also includes the biovariety diacteylactis, which is a citrate-fermenting variant of the L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype, and the corresponding metabolic pathway is generally encoded on a plasmid (6, 22).

Phenotypes are of primary importance for screening of potential starter cultures because of their postulated linkage to performance in the fermentation. However, molecular characterization of field isolates often does not match with their subspecies designation based on the phenotypes (2, 13, 23, 25). Fingerprinting studies reveal two main genomic lineages: the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype (a genotype similar to that of the L. lactis subsp. cremoris type strain SK11) and the L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype (a genotype similar to that of the L. lactis subsp. lactis type strain IL1403). The L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype lineage mainly comprises L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains, but the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype lineage often harbors both L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotypes, hampering the development of genetic markers for a certain phenotype or trait. The discrepant strains have an L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype, while they display an L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype (8, 11, 14, 16, 26), and the MG1363 L. lactis subsp. cremoris lab strain is the well-known representative for these frequently encountered diverging strains.

Current genomic fingerprinting studies are far from the resolution level required to reveal a phenotype-specific genetic signature. High-resolution fingerprinting, optimized for the species of interest, may deliver phenotype-specific genetic markers that could be employed as an effective alternative to the labor-intensive phenotypic screens. Additionally, the markers generated for a particular strain can be used as a signature to determine their presence and abundance in the commercial mixed-culture fermentations (7, 10, 18) and/or for source tracking (19). Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis is a fingerprinting technique that offers high reproducibility, superior resolution, and the highest correlation to DNA-DNA hybridizations, although repetitive sequence-based PCR (Rep-PCR) and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis are more frequently applied (3, 11, 15, 24, 27).

This study aimed to develop an optimized, high-throughput, and high-resolution AFLP methodology for L. lactis strains derived from different ecological niches around the world. High throughput was implemented by the use of fluorophore labels in combination with capillary electrophoresis. The large genetic diversity within the 82-strain collection used in this study allowed true validation of the resolution power and the species-wide applicability of the method. Moreover, AFLP fingerprinting of strains with discrepant genotype-phenotype characteristics enabled the identification of L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype-specific genetic markers, for which the robustness was verified for many representative strains next to the well-known representative reference strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A collection of 82 L. lactis strains of diverse geographical origins and isolation sources was used in this study. The designations of the strains and their origins, subspecies, and genotype information are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Strains were routinely grown in M17 broth (Oxoid Ltd.) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17).

Chromosomal DNA isolation.

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was isolated with a tissue and culture DNA isolation kit (Qiagen GmbH) according to the manufacturer′s instruction. Chromosomal DNA quality and concentrations were determined with a Nanodrop device (Coleman Technologies Inc.) and 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gels.

AFLP prescreening using radioactive detection.

Enzyme-primer combinations likely to allow high-resolution fingerprinting were selected using the web-based simulation of double-digestion fingerprinting techniques tool (17). The published L. lactis genomes of strains SK11 (9), IL1403 (1), and MG1363 (29) were double digested using combinations of HindIII and EcoRI as rare cutters and TaqI and MseI as frequent cutters. Selective PCR was simulated by adding single 3′-end-selective nucleotides for each primer. Enzyme-primer combinations producing 60 to 100 well-distributed fragments in silico were applied during experimental prescreening on L. lactis subsp. cremoris NIZO B32, L. lactis subsp. lactis NIZO B644 and NIZO B2211, and L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis NIZO B1592, according to the protocol of Vos et al (28) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

AFLP methodology using fluorophore detection and capillary electrophoresis.

Adaptor annealing, restriction, and ligation reactions were based on the AFLP protocol by Meudt and Bayly (10). Chromosomal DNA (250 ng) was used for the template preparations. Adaptors and selective primers (Table 1) were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands), and the HindIII selective primer was end labeled with the fluorophore 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). AFLP reactions were optimized on the basis of the protocol of Vos et al. (28) and Meudt and Bayly (10), with the following modifications. Preselective PCR was completely omitted from the protocol. Selective PCR was performed using 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in a 25-μl volume containing 1 μM TaqI and HindIII selective primers, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 5 μl ligation products (diluted 15 times). PCR amplification using a Westburg Biometria T1 cycler was initiated by 2 min of nick filling at 72°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 60 s annealing at 50°C, and 60 s extension at 72°C, and was completed with a 10-min final extension step at 72°C. The ramping speed was fixed at 5°C/s. One microliter PCR products (diluted 3 times) was mixed with 9 μl ET550-R size standard (diluted 36 times; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and analyzed on a MegaBACE 500 automated DNA platform (GE Healthcare, Diegem, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

Adaptors and primers

| Primer name | Sequence | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Primer name | Sequence | Label |

| HindIII linker 1 | 5′-CTCGTAGACTGCGTACC-3′ | No label |

| HindIII linker 2 | 5′-AGCTGGTACGCAGTC-3′ | No label |

| HindIII core primer | 5′-GACTGCGTACCAGCTT-3′ | No label |

| HindIII selective primer (H1) | 5′-GACTGCGTACCAGCTTA-3′ | FAM |

| 195bp HindIII selective primer | 5′-GACTGCGTACCAGCTTATCAA-3′ | FAM |

| TaqI linker 1 | 5′-CGGTCAGGACTCAT-3′ | No label |

| TaqI linker 2 | 5′-GACGATGAGTCCTGAC-3′ | No label |

| TaqI core primer | 5′-CGATGAGTCCTGACCGA-3′ | No label |

| TaqI selective primer (T1) | 5′-GATGAGTCCTGACCGAA-3′ | No label |

| 195-bp TaqI selective primer | 5′-GATGAGTCCTGACCGAATATC-3′ | No label |

| 195-bp normal PCR forward primer | 5′-CCGCCAGATTCGAATATC-3′ | No label |

| 195-bp normal PCR reverse primer | 5′-CAAATGGAAGCTTATCAA-3′ | No label |

AFLP profile analysis.

Data were analyzed using the BioNumerics (version 4.5) software suite (Applied Maths, Sint Martens-Latem, Belgium). Pairwise similarities were calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient, and cluster analyses were performed by applying the unweighted-pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) algorithm for the range of 80 to 400 bp within the AFLP profiles.

Identification of subspecies phenotype-specific markers on fingerprints.

The candidate phenotype markers unique for the L. lactis subsp. cremoris or L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype were searched for within the AFLP patterns and traced back to the reference genomes with the web-based simulation of double-digestion fingerprinting techniques tool (17). The original length of the digests was calculated by subtracting the number of nucleotides coming from adaptor sequences. The sequences of the fragments were exported from the sequence link available in the web-based simulation of double-digestion fingerprinting techniques tool (17). The positions of the candidate markers and probable mutations on reference genomes (strains MG1363, SK11, and IL1403) were checked by BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) analysis in the NCBI nr-nucleotide database. The gene-specific PCR and AFLP PCR primers were designed according to sequences obtained from the BLAST hits. The AFLP primers were extended with 3 more selective nucleotides from each end to increase their selectivity for the marker fragment sequence (Table 1), and the presence of marker fragments was confirmed by gene-specific PCR and refined AFLP amplifications.

Phenotypic diversity analysis.

Phenotypic differentiation of lactococcal subspecies and biovarieties was achieved using the previously established phenotypic analysis, including tests for 4% (wt/vol) NaCl resistance, citrate utilization, arginine hydrolysis, and maltose utilization (14). In addition to these standard tests for subspecies differentiation, several other phenotypic data sets have been used, including enzyme activities; sugar fermentation capacity profiles; polysaccharide utilization profiles; and antibiotic, metal ion, and nisin sensitivities. The details of the phenotypic testing protocols are given in the supplemental material. The determination of phenotypic diversity among strains was facilitated by UPGMA cluster analysis based on the Canberra metric coefficient, separately for each data set. The congruence of groupings on the basis of separate phenotypic data sets and the AFLP data was calculated using the Pearson correlation.

RESULTS

Methodology implementation and reproducibility analysis.

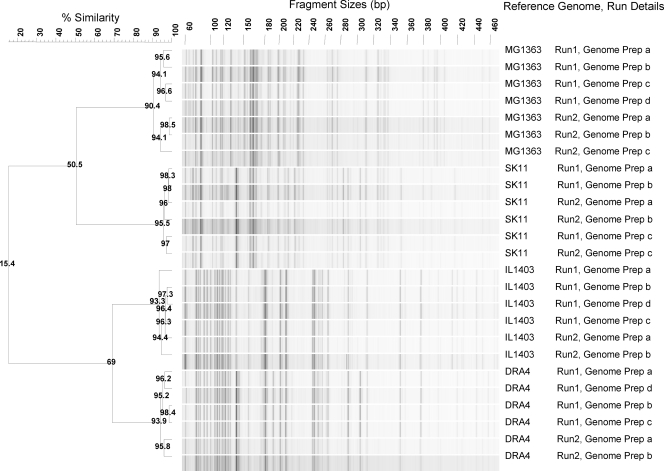

Twenty-four enzyme-primer combinations were selected on the basis of in silico analysis and verified experimentally using the classical AFLP approach that makes use of radioactive labeled primers and slab gel analyses (28) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The HindIII-TaqI restriction combination revealed the highest number of polymorphisms, including 19 AFLP markers discriminating between the reference strains tested (see Materials and Methods for details). This combination was subsequently used for genomic diversity analysis of the natural isolates using fluorophore-labeled primers (see the supplemental material for details). Following optimization, the eventual standard procedure involved a relatively straightforward protocol that does not require preamplification, touchdown PCR, or slow-ramping PCR procedures. The discriminatory power of AFLP fingerprinting is determined not only by the number of polymorphisms generated but also by the level of reproducibility. To evaluate the reproducibility of the AFLP protocol, independent replicates were generated for the 4 reference L. lactis strains, 3 of which were used for in silico simulations. The variation as a consequence of genome preparations was not significant within a single experiment, but the reproducibility was predominantly affected by the variations between independent AFLP experiments, resulting in distinct clusters for strain MG1363 and strain DRA4 (Fig. 1). On the basis of this analysis, 90% similarity was taken as a threshold for the separation of individual strains.

Fig. 1.

Reproducibility evaluation for the reference strains of Lactococcus lactis. Runs 1 and 2 correspond to independent AFLP experiments, and genome preparations (Prep) a, b, c, and d correspond to independent genome preparations of the same strain. UPGMA clusterings were based on the Pearson correlation coefficient over a range of 80 to 400 bp.

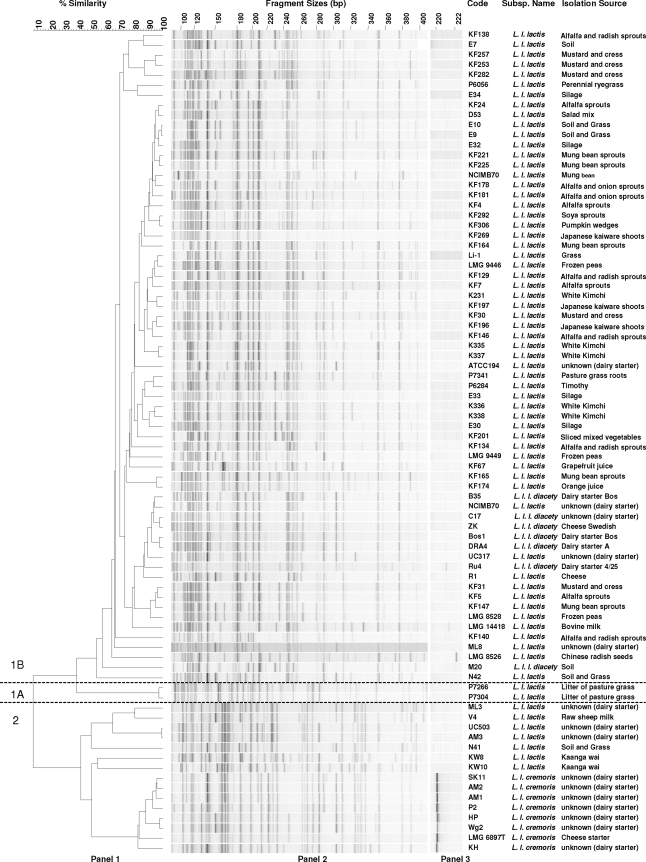

Diversity analysis of field isolates.

AFLP profiles were generated for 82 dairy and nondairy isolates of L. lactis. Cluster analysis revealed two main AFLP clusters with a resolution of 15% similarity for L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype discrimination (Fig. 2). The AFLP profiles of the L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype cluster were further separated into two distinct clusters. Cluster 1B contained the majority of the L. lactis subsp. lactis strains and all of the biovar diacetylactis strains. Notably, all dairy-associated biovar diacetylactis strains clustered together but were distinguished from strain M20, which was isolated from soil. The smaller cluster 1A contained two strains (L. lactis subsp. lactis NIZO B2207 and NIZO B2208) isolated from litter of pasture grass with indistinguishable AFLP profiles (Fig. 2). These cluster 1A isolates were previously proposed to be members of a third L. lactis genomic lineage (14). It is characterized by an L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype but displays neither an L. lactis subsp. lactis nor an L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype on the basis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence and multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA). The AFLP analysis enables their distinction as a unique genotype at a high resolution. L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype cluster 2 included all strains displaying a typical L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype but also encompassed a subset of strains with an L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype. The L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype strains grouped together with similarities exceeding 80% and formed a distinct subcluster, while the L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains were too diverse to form a distinct subcluster.

Fig. 2.

AFLP on L. lactis natural isolates. Panel 1, UPGMA clustering of AFLP profiles with Pearson correlation; panel 2, AFLP profiles of isolates, 80 to 400 bp; panel 3, 221-bp marker (corresponding to the 195-bp digest) selectively isolated by the addition of 3 more nucleotides to the end of original HindIII-TaqI restriction combination primers.

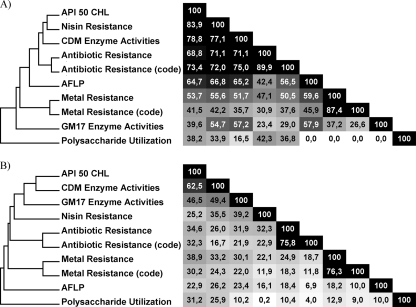

The possible correlations between specific phenotypic traits and AFLP clustering were further investigated for the L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype clusters (clusters 1 and 2, respectively) to evaluate whether strain-discriminating phenotypes were reflected in the AFLP profiles. Within the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype cluster, API 50 carbohydrate fermentations, nisin sensitivity, and enzyme activity levels measured in chemically defined medium (CDM; see methods in the supplemental material for details) correlated relatively well with the AFLP-based clustering (Fig. 3 A; product moment correlation range, 60 to 70%). In contrast, other phenotypic traits like polysaccharide utilization, enzyme activity levels in GM17, and antibiotic and metal resistance did not show a significant correlation with the AFLP clustering. Notably, none of the phenotypic differences between strains within the L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype clusters (1A and 1B) appeared to correspond to AFLP profile differences (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Correlations between phenotype variations (see Tables S2 to S7 in the supplemental material) and AFLP clusterings for L. lactis subsp. cremoris (A) and L. lactis subsp. lactis (B) genotype clusters.

AFLP markers discriminating L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotypes.

In addition to strain-specific discrimination, the AFLP patterns generated in this study enabled the identification of marker fragments for the L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype. The pair of fragments between 212 and 214 bp and the triplet of fragments between 220 and 223 bp were consistently observed in the AFLP profiles of L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype strains but were absent in the profiles generated for L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains, irrespective of their genotype. The 221-bp (195-bp, when the number of nucleotides coming from adaptor sequences is subtracted) L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype-specific fragment was selected for further validation. BLAST analysis indicated that the corresponding gene encodes LACR_2087, a hypothetical membrane protein (GenBank accession number YP_811677) that is present in both the strain SK11 and strain MG1363 genomes but absent in the strain IL1403 genome. The corresponding gene on the MG1363 genome has a single nucleotide substitution that abolishes the HindIII restriction site, as well as some other substitutions affecting the selective nucleotides adjacent to this site, explaining the lack of this marker fragment in the MG1363 AFLP fingerprint. The genomic region in which LACR_2087 is encoded appeared to be hypervariable, with many gene deletions in MG1363 compared to the sequence of SK11, such as the deletion of LACR_2089, a phage-related hypothetical protein; LACR_2088, a cell wall-associated hydrolase; and LACR_2085, a hypothetical protein that may be linked to the L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype. Moreover, the 82 isolates were screened both with gene-specific PCR and with more stringent AFLP targeting of the 195-bp fragment. The gene-specific PCR generated the anticipated product in all L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype strains, while no products were obtained for strains exhibiting an L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype. High-stringency AFLP PCR confirmed that the 221-bp fragment could consistently be generated in L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype strains, thereby proving that the 195-bp fragment indeed is responsible for the generation of the observed 221-bp marker in the AFLP analyses (Fig. 3). Additional reference strains as well as novel isolates displaying either the L. lactis subsp. cremoris or L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype were also tested for the robustness of these marker fragments. All novel L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype isolates produced the marker fragments, while they were consistently absent for the L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains (data not shown). These experiments establish that the marker fragment identified here is an appropriate and generic marker to distinguish L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains at the genetic level.

DISCUSSION

The present study delivers a high-resolution AFLP protocol for Lactococcus lactis that was adapted to a fluorophore-labeled procedure for high-throughput screenings. In contrast to many AFLP protocols described (28), the optimized procedure does not include a preselection and touchdown PCR procedure and employs fast ramping cycles. The validity of the AFLP methodology developed was established with a collection of 82 L. lactis strains that has previously served as a benchmark strain collection in other strain-typing efforts, including 16S rRNA analysis, 5-locus MLSA, and Rep-PCR genomic fingerprint analysis (14). The resolution power of AFLP-based fingerprinting, with a cutoff value of 15% similarity for L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype discrimination, vastly exceeds the resolution power of Rep-PCR, which has a 40% similarity cutoff for subspecies discrimination. Published AFLP studies for other species usually offer values of 60 to 90% and 40 to 60% for intra- and interspecies variations, respectively, on the basis of UPGMA clustering with the Pearson correlation coefficient (7, 15, 18). The AFLP dendrogram also shared its clustering topology with the dendrograms obtained from MLSA and 16S rRNA homology analysis (16). Recently, a subset of the strain collection used in this study was also subjected to a genome-scale diversity analysis by comparative genome hybridization (CGH) (21). The comparison of AFLP and CGH dendrograms showed similar clustering of the strains with an L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype within the L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotype cluster and an analogous compact clustering for L. lactis subsp. lactis genotype strains, with outlying members of the third genomic lineage (strains P7304 and P7266) detected. These comparisons demonstrate the resolution capacity of the AFLP methodology, which enables strain-specific typing with high reliability and biological relevance.

The commonly observed phenotype-genotype mismatching has directed many researchers to generate genetic markers linked to these so-called L. lactis subsp. cremoris and L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotypes. A method based on probing of EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA with a his operon gene probe enabled differentiation of L. lactis subsp. lactis phenotype strains with different genomic makeups (5). An elegant restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis approach targeting the gadB gene was also able to determine both the phenotype and the genotype at the same time (12). However, their robustness remains to be confirmed since they were validated with only one discrepant strain (MG1363) (2, 4). The L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype-specific marker fragments generated in this study provide subspecies phenotype information within the fingerprint. Elaborating on this concept, markers that are representative for a particular phenotypic trait can be developed rationally. For example, a phenotypic trait related to a specific gene can be screened for in the simulation tool with different enzyme-primer combinations for the generation of AFLP markers, which might be amplified for the strains carrying the functional gene of interest and absent for the others. Such a strategy potentially provides effective genetic markers for screening of large strain collections for the phenotype of interest, in addition to the genomic diversity information.

The AFLP procedure presented here also provides a tool for the analysis of population dynamics in industrial fermentation processes that employ microbial consortia of closely related strains, such as a starter culture (e.g., Gouda cheese production). Identification of strain-specific markers by an approach analogous to the approach presented for the L. lactis subsp. cremoris phenotype may allow the design of strain-specific primers for tracing and quantification of the strains without reisolation or viable count enumeration at different time points during fermentation or under different processing conditions. It is a valuable tool to determine the number of genomic lineages present in isolated collections of strains, which in turn justifies selection of representative strains for whole-genome sequencing.

In conclusion, the AFLP protocol developed for L. lactis enables the delineation of closely related strains, and its reproducibility and resolution exceed those of other currently available methods. Advanced analysis of the AFLP profiles in combination with in silico genome analysis can facilitate the recognition of genetic markers responsible for specific phenotypic traits. Furthermore, the high-throughput strain-typing method using a genetic marker which accurately predicts the phenotype allows fast and predictive screening of culture collections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Hanneke Witsenboer from Keygene B.V. for her support with the radiolabeling-based AFLP screenings. Furthermore, we acknowledge Jumna Murat Bayjanov, Roland Siezen, and Sacha van Hijum for kindly providing dendrograms produced for comparative genome hybridization data and also for their valuable comments. We also acknowledge Herwig Bachmann for sharing phenotype data and Jan Hoolwerf for technical assistance. Finally, we thank Patrick Janssen, Ingrid van Alen, and Lucie Hazelwood for all the useful discussions and technical support.

This work was funded by the Top Institute Food and Nutrition (TIFN) and is part of the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation, a Centre of Excellence of The Netherlands Genomics Initiative.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bolotin A., et al. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de la Plaza M., et al. 2006. Discrepancies between the phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Lactococcus lactis cheese isolates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43:637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foschino R., et al. 2008. Comparison of Lactococcus garvieae strains isolated in northern Italy from dairy products and fishes through molecular typing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105:652–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garvie E. I., Farrow J. A. E. 1982. Streptococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (Orla-Jensen) comb. nov. and Streptococcus lactis subsp. diacetilactis (Matuszewski et al.) nom. rev., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 32:453–455 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Godon J. J., Delorme C., Ehrlich S. D., Renault P. 1992. Divergence of genomic sequences between Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:4045–4047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hugenholtz J. 1993. Citrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:165–178 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janssen P., et al. 1997. Discrimination of Acinetobacter genomic species by AFLP fingerprinting. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1179–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelly W., Ward L. 2002. Genotypic vs. phenotypic biodiversity in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology 148:3332–3333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Makarova K., et al. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15611–15616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meudt H. M., Bayly M. J. 2008. Phylogeographic patterns in the Australasian genus Chionohebe (Veronica s. l., Plantaginaceae) based on AFLP and chloroplast DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 47:319–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nomura M., Kobayashi M., Narita T., Kimoto-Nira H., Okamoto T. 2006. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Lactococcus lactis from milk and plants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:396–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nomura M., Kobayashi M., Okamoto T. 2002. Rapid PCR-based method which can determine both phenotype and genotype of Lactococcus lactis subspecies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2209–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pu Z. Y., Dobos M., Limsowtin G. K., Powell I. B. 2002. Integrated PCR-based procedures for the detection and identification of species and subspecies of the Gram-positive bacterial genus Lactococcus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rademaker J. L., et al. 2007. Diversity analysis of dairy and nondairy Lactococcus lactis isolates, using a novel multilocus sequence analysis scheme and (GTG)5-PCR fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7128–7137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rademaker J. L., et al. 2000. Comparison of AFLP and rep-PCR genomic fingerprinting with DNA-DNA homology studies: Xanthomonas as a model system. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 (Pt 2): 665–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salama M. S., Sandine W. E., Giovannoni S. J. 1993. Isolation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris from nature by colony hybridization with rRNA probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3941–3945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. San Millan R., Garaizar J., Bikandi J. 2005. In silico simulation of fingerprinting techniques based on double endonuclease digestion of genomic DNA. In Silico Biol. 5:341–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Savelkoul P. H., et al. 1999. Amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis: the state of an art. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3083–3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheirlinck I., Van der Meulen R., De Vuyst L., Vandamme P., Huys G. 2009. Molecular source tracking of predominant lactic acid bacteria in traditional Belgian sourdoughs and their production environments. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1081–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schleifer K. H., et al. 1985. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 6:183–195 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siezen R. J., et al. 2011. Genome-scale diversity and niche adaptation analysis of Lactococcus lactis by comparative genome hybridization using multi-strain arrays. Microb. Biotechnol. 4:383–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stiles M. E., Holzapfel W. H. 1997. Lactic acid bacteria of foods and their current taxonomy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36:1–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tanigawa K., Kawabata H., Watanabe K. 2010. Identification and typing of Lactococcus lactis by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4055–4062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thompson F. L., Hoste B., Vandemeulebroecke K., Swings J. 2001. Genomic diversity amongst Vibrio isolates from different sources determined by fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24:520–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Urbach E., Daniels B., Salama M. S., Sandine W. E., Giovannoni S. J. 1997. The ldh phylogeny for environmental isolates of Lactococcus lactis is consistent with rRNA genotypes but not with phenotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:694–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Hylckama Vlieg J. E., et al. 2006. Natural diversity and adaptive responses of Lactococcus lactis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ventura M., Zink R. 2002. Specific identification and molecular typing analysis of Lactobacillus johnsonii by using PCR-based methods and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 217:141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vos P., et al. 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4407–4414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wegmann U., et al. 2007. Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 189:3256–3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.