Abstract

Francisella novicida is a close relative of Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia. The genomes of F. novicida-like clinical isolates 3523 (Australian strain) and Fx1 (Texas strain) were sequenced and compared to F. novicida strain U112 and F. tularensis strain Schu S4. The strain 3523 chromosome is 1,945,310 bp and contains 1,854 protein-coding genes. The strain Fx1 chromosome is 1,913,619 bp and contains 1,819 protein-coding genes. NUCmer analyses revealed that the genomes of strains Fx1 and U112 are mostly colinear, whereas the genome of strain 3523 has gaps, translocations, and/or inversions compared to genomes of strains Fx1 and U112. Using the genome sequence data and comparative analyses with other members of the genus Francisella, several strain-specific genes that encode putative proteins involved in RTX toxin production, polysaccharide biosynthesis/modification, thiamine biosynthesis, glucuronate utilization, and polyamine biosynthesis were identified. The RTX toxin synthesis and secretion operon of strain 3523 contains four open reading frames (ORFs) and was named rtxCABD. Based on the alignment of conserved sequences upstream of operons involved in thiamine biosynthesis from various bacteria, a putative THI box was identified in strain 3523. The glucuronate catabolism loci of strains 3523 and Fx1 contain a cluster of nine ORFs oriented in the same direction that appear to constitute an operon. Strains U112 and Schu S4 appeared to have lost the loci for RTX toxin production, thiamine biosynthesis, and glucuronate utilization as a consequence of host adaptation and reductive evolution. In conclusion, comparative analyses provided insights into the common ancestry and novel genetic traits of these strains.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is an intracellular pathogen that causes tularemia in humans, and the public health importance of this bacterium has been well documented in recent history (81). The genome sequences of several F. tularensis isolates from disparate geographic origins have been sequenced to date (4, 6, 12, 13, 41). Comparative genome sequence analyses have provided insights into the taxonomy, physiology, and pathogenic evolution of different subspecies of F. tularensis (33, 91). Francisella novicida strain U112, which is β-galactosidase negative but citrulline ureidase and glycerol positive, originally was isolated from water collected in the Ogden Bay Bird Refuge in Utah (39). Early comparative studies indicated that F. novicida strain U112 is less fastidious than F. tularensis, and it differs from the latter in antigenic composition as well as virulence (64). The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of F. novicida strain U112 also is structurally distinct and biologically more active than F. tularensis LPS (87, 92). Nevertheless, F. novicida strain U112 has been used as a surrogate of F. tularensis in scores of laboratory studies, primarily due to its pathogenicity for rodents and amenability to genetic manipulation (24).

F. novicida was formally included in the genus Francisella in 1959, and strain U112 was the sole member of the species until 1989 (62). Since then, there have been at least seven reports of F. novicida or F. novicida-like bacteria isolated from humans. These include the earliest human isolates described by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from Louisiana and California (30), two isolates from Texas (15), and an isolate each from Australia (95), Thailand (42), and Arizona (8).

Some of these reports were from immunocompromised patients who manifested a localized, relatively mild illness, which is consistent with F. novicida being an opportunistic pathogen. Despite these reports, F. novicida is thought to constitute an environmental lineage along with Francisella philomiragia, which also has been associated with human disease (30, 94).

The genome of F. novicida strain U112 has been sequenced and compared to the genome sequences of F. tularensis pathogenic to humans (75). The draft genome sequences of Francisella isolates from Louisiana and California (GA99-3548 and GA99-3549, respectively) also have been compared to the genome sequences of F. tularensis strains (12). The draft genome sequences of F. novicida strains FTE (a mouse passage of strain U112; GenBank project number 30717) and FTG (a human isolate; GenBank project number 55313) are available. Whereas F. tularensis is a highly infectious zoonotic agent, the mechanism of transmission of F. novicida among vertebrate or invertebrate species is unknown. Despite the presence of ≥97.7% average nucleotide identities among the genome sequences of F. novicida and F. tularensis strains, they have been proposed to constitute separate species based on evolutionary analyses (40). However, amending the genus Francisella and the reclassification of F. novicida as a subspecies of F. tularensis have been formally proposed (31).

Francisella isolate Fx1, which is β-galactosidase, β-lactamase, and citrulline ureidase positive but glycerol negative, was cultured from the blood of a diabetic patient in the Galveston Bay area of Texas (15). The patient was thought to have disseminated infection due to isolate Fx1 manifesting with bacteremia, pneumonia, and brain abscesses. Virulence studies in laboratory animals performed by standard methods showed no difference between F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and isolate Fx1 (15). Subsequent studies have designated this isolate F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain Fx1 and F. novicida strain Fx1 (22, 66). Francisella isolate 3523, the first reported Francisella from the Southern Hemisphere, was cultured from a patient who had cut a toe in brackish water in the Northern Territory of Australia (95). The patient was afebrile, had no other clinical symptoms, and recovered after antibiotic treatment. Studies using Swiss-Webster mice showed that isolate 3523 was less virulent than F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (95). The true nature of this isolate, which is glycerol and β-galactosidase positive, is unknown and has been tentatively designated a novicida-like subspecies of F. tularensis (95). Since these isolates were from different continents/hemispheres, they were desirable candidates for genome sequencing and comparative analyses. The objectives of the present study were to decipher the genomes of F. novicida-like strains Fx1 and 3523 and to identify the genetic differences between these strains and F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 by comparative genome analyses. Since genetic relationships and evolutionary contexts could be better understood by whole-genome analyses of conserved operons, it was envisaged to include the genomes of different Francisella species and strains in the comparisons when available.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultivation and chromosomal DNA extraction were performed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO, using standard protocols (57, 66). Genomic library construction, sequencing, and finishing were performed at the Genome Science Facilities of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico, as described previously (4, 6, 98). The prediction of the number of subsystems and pairwise BLAST comparisons of protein sets within strains Fx1 and 3523 were performed using Rapid Annotation using Subsystems Technology (RAST), which is a fully automated, prokaryotic genome annotation service (3). Proteins deemed to be specific to each strain were compared against the NCBI nonredundant protein database to determine whether they were hypothetical or conserved hypothetical. If there was no adequate alignment with any protein (less than 25% identity or the aligned region is less than 25% of the predicted protein length), the translated open reading frame (ORF) was designated a hypothetical protein.

Multiple genome comparisons were performed using the progressive alignment option available in the program MAUVE, version 2.3.0. Default scoring and parameters were used for generating the alignment. A synteny plot was generated using the program NUCmer. The program uses exact matching, clustering, and alignment extension strategies to create a dot plot based on the number of identical alignments between two genomes. Prophage regions (PRs) were identified using Prophinder (http://aclame.ulb.ac.be/Tools/Prophinder/), an algorithm that combines similarity searches, statistical detection of phage gene-enriched regions, and genomic context for prophage prediction. Insertion sequences (ISs) were identified by whole-genome BLAST analysis of strains Fx1, 3523, and U112 using the IS finder (http://www-is.biotoul.fr/). Gene acquisition and loss among the three strains were determined by comparing gene order, orientation of genes (forward/reverse), GC content of genes (the percentage above or below the whole-genome average), features of intergenic regions (e.g., remnants of IS elements, integration sites, etc.), and the similarity of proteins encoded by genes at a locus of interest (>90% identity at the predicted protein level).

DNA and protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html) and BOXSHADE (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html) programs as described previously (80). Multiple-sequence alignments for phylogenetic analyses of strains 3523 and Fx1 were performed using the program MUSCLE, which is available at the website http://www.phylogeny.fr/ (20, 21). The alignment was followed by a bootstrapped (n = 100) neighbor-joining method for inferring the phylogenies (85). Only full-length 16S rRNA and succinate dehydrogenase (sdhA) gene sequences from high-quality, finished Francisella genomes were included in these comparisons.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General features of the chromosomes.

The chromosome of strain 3523 was 31,692 bp larger than that of strain Fx1. Although the chromosomes of strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 differed in size, their average GC content and the percentage of sequence that encodes proteins were similar (Table 1). Genomic islands (GIs) are clusters of genes in prokaryotic genomes of probable horizontal origin (38). Comparative genomic analysis indicated that strain 3523 contained two GIs (GI1, 4,352 to 15,978 bp, 28.8% GC; GI2, 1,012,013 to 1,056,964 bp, 34.2% GC). Strain U112 also contained two genomic islands (GI1, 4,244 to 15,027 bp, 29.2% GC; GI2, 369,322 to 376,086 bp, 30.7% GC). However, strain Fx1 contained a single genomic island (GI1, 4,244 to 13,232 bp, 27.9% GC). Whereas GI2 of strain 3523 was unrelated to GI2 of strain U112, GI1 of strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 were related to each other, suggesting a common lateral origin. Interestingly, none of these GIs contained genes that have a role in pathogenicity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the genomes of strains U112, Fx1, and 3523

| Strain | Chromosome size (bp) | No. of protein-coding genesa | No. of subsystemsa | GC content (%) | No. of rRNA or tRNA genesb |

GenBank accession no. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5S | 23S | 16S | tRNA | ||||||

| U112 | 1,910,031 | 1,821 | 250 | 32.48 | 3 + 1 | 3 | 3 | 38 | CP000439 |

| Fx1 | 1,913,619 | 1,819 | 253 | 32.54 | 3 + 1 | 3 | 3 | 38 | CP002557 |

| 3523 | 1,945,310 | 1,854 | 253 | 32.32 | 3 + 1 | 3 | 3 | 37 | CP002558 |

Genes and subsystems predicted by RAST server.

Each strain contains three rRNA operons (5S-23S-16S) and an orphan 5S rRNA fragment.

Short sequence repeats, which include insertion sequences (IS), are the hallmark of F. tularensis genomes, and the IS elements are thought to be generally stable among different isolates despite their diverse geographical origins (75, 86). Whole-genome BLASTN and BLASTX analyses using IS finder showed that strain 3523 contained a single copy of an IS481 family element (FN3523_0714, 348 amino acids [aa]) that had no homologs in strains Fx1 and U112. Strain Fx1 contained six copies of the IS110 family element (FNFX1_0028, FNFX1_1255, FNFX1_1555, and FNFX1_1557, 315 aa each; FNFX1_0715 and FNFX1_0718, 290 aa each) that had no homologs in strains 3523 and U112. Strains 3523 and Fx1 contained IS982 family elements (FN3523_1458, 258 aa; FNFX1_0226, 187 aa) that had no homologs in strain U112. Whereas strain 3523 lacked ISFtu1, ISFtu3, and ISFtu5 sequences, strain Fx1 lacked only ISFtu5 sequences. Nevertheless, both strains contained full-length or partial homologs of other ISFtu elements in various copy numbers (data not shown).

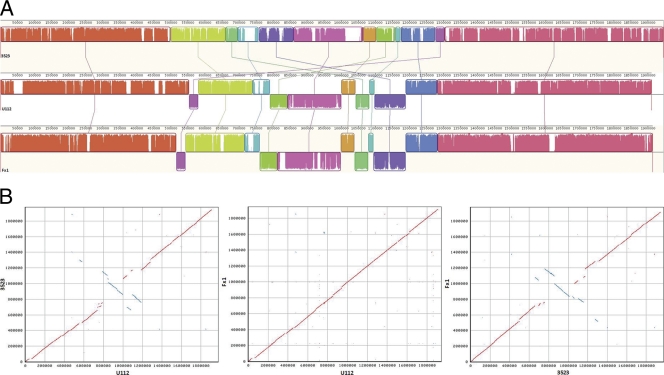

Whole-genome alignment using MAUVE showed the presence of extensive blocks of homologous regions among strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 (Fig. 1A). NUCmer analyses revealed that the genomes of strains Fx1 and U112 were mostly colinear, whereas the genome of strain 3523 had gaps, translocations, and/or inversions compared to the genomes of strains Fx1 and U112 (Fig. 1B). In-depth sequence examination indicated that some of these gaps and/or inversions were associated with integrative and conjugative elements, including the IS elements mentioned above. The occurrence of IS elements at genomic breakpoints also has been observed in comparisons of the genomes of different subspecies of F. tularensis (75).

Fig. 1.

(A) Alignment of the chromosomes of strains Fx1, U112, and 3523 using MAUVE 2. Identically colored boxes, known as locally colinear blocks (LCBs), depict homologous regions in the three chromosomes. The edges of LCBs indicate chromosome rearrangements due to recombination, insertions, and/or inversions. Sequences of strains Fx1 and U112 inverted in relation to those of strain 3523 are shown as blocks below the horizontal line. The vertical lines connecting the LCBs point to regions of homology among the three chromosomes. Numbers above the maps indicate nucleotide positions within the respective chromosomes. (B) Synteny plots of the chromosomes of strains Fx1, U112, and 3523 generated by NUCmer. Each plot shows regions of identity between the chromosomes based on pairwise alignments. Plus-strand matches are slanted from the bottom left to the upper right corner and are shown in red. Minus-strand matches are slanted from the upper left to the lower right and are shown in blue. The number of dots/lines shown in the plot is the same as the number of exact matches found by NUCmer. Numbers indicate nucleotide positions within the respective chromosomes.

BLAST comparison of protein sets.

A three-way comparison of strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 revealed that they contained 1,583 orthologous protein-coding genes (bidirectional best hits). A similar comparison indicated that strain 3523 contained 149 protein-coding genes with no homologs in strains Fx1 and U112. Strain Fx1 contained 70 protein-coding genes with no homologs in strains 3523 and U112. Strain U112 contained 69 protein-coding genes with no homologs in strains 3523 and Fx1. A two-way comparison of protein-coding genes of strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. In strain 3523, 494 genes could not be assigned a function based on BLAST analysis and therefore had been annotated as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins. In strain Fx1, 447 genes had been annotated as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins.

Iron metabolism and FPI genes.

A cluster of 17 to 19 genes has been proposed to constitute the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI), and it is found in a single copy in F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 (FTN_1309 to FTN_1325), but it is duplicated in the genomes of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (75, 91). Genome comparisons revealed that strains 3523 and Fx1 also contained a single copy of the FPI (FN3523_1373 to FN3523_1389 and FNFX1_1347 to FNFX1_1363, respectively). The order and orientation of genes within the FPI of strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 were identical. The predicted proteins within the putative FPIs of strains 3523 and Fx1 had average identities of 87 and 97%, respectively, to those from strain U112. Furthermore, strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 contained the ferric uptake regulator gene (fur) as well as the fslABCDEF operon (FN3523_1749 to FN3523_1755, FNFX1_1722 to FNFX1_1728, and FTN_1681 to FTN_1687, respectively), which is implicated in the biosynthesis of a polycarboxylate siderophore in F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain Schu S4 and F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 (37, 71). An ortholog of strain Schu S4 fupA (FTT0918), whose product is required for the efficient utilization of siderophore-bound iron (47), also was found in strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 (FN3523_0408, FNFX1_0437, and FTN_0444, respectively). The presence of FPI, fur, fslABCDEF, and fupA in almost all Francisella genomes suggests that these functions are essential for their survival in the environment and/or host.

RTX toxin-related genes.

Several pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria produce potent pore-forming cytotoxins that contain calcium-binding glycine and aspartate-rich repeat regions (93). The genetic determinants of RTX toxin synthesis and transport usually consist of a single operon (rtxCABD) and an unlinked gene (tolC) encoding an outer membrane channel (46). Although some researchers have alluded to the presence of toxins in cellular preparations of F. tularensis, there is no consensus opinion on the synthesis of toxins, and genes encoding toxins have not been found in this species (69, 90). However, homologs of tolC (FTT_1095c and FTT_1724c) have been characterized in F. tularensis (25) and also are found in strains U112 (FTN_0779 and FTN_1703), 3523 (FN3523_1096 and FN3523_1775), and Fx1 (FNFX1_0783 and FNFX1_1744).

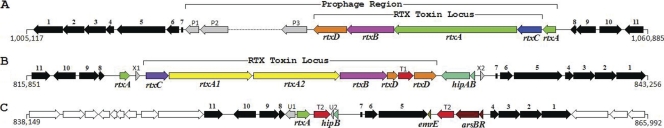

The predicted prophage region of strain 3523 contained an operon (10,160 bp, 35.5% GC) related to those involved in RTX toxin synthesis and secretion (Fig. 2A). The first ORF (FN3523_1037, rtxC) had no homologs in the databases. Based on its location within the operon and predicted protein molecular mass (356 aa, 41.81 kDa), rtxC may encode a protein involved in fatty acylation during the activation of protoxin to cytotoxin. The second ORF (FN3523_1036, rtxA) encoded a putative protein (1,829 aa, 195 kDa) that had 30% identity to the RTX cytotoxin-related FrpC protein (1,829 aa, 197 kDa) of Neisseria meningitidis FAM20 (88) and α-hemolysin HlyA (1,024 aa, 110 kDa) of Escherichia coli (82). The third ORF (FN3523_1035, rtxB) encoded a putative ABC transporter (703 aa, 79.83 kDa) that had 50% identity to the α-hemolysin translocator ATP-binding protein HlyB (706 aa, 79.83 kDa) of E. coli (29). The fourth ORF (FN3523_1034, rtxD) encoded a putative membrane fusion protein (490 aa, 56.41 kDa) that had 32% identity to the type 1 translocator protein HlyD (478 aa, 54.48 kDa) of E. coli (67). The toxin-encoding ORF (FN3523_1036, 5,490 bp) was the largest among all protein-coding genes predicted in strain 3523. Several other Francisella genomes contained truncated genes related to rtxA of strain 3523 (e.g., FTM_1222, FTL_1124, FTT_1077c, FTH_1098, and FTA_1184; 76 to 94% identity at the predicted protein level). However, homologs of rtxB, rtxC, and rtxD were not found in any of these genomes.

Fig. 2.

(A) RTX toxin locus of strain 3523. Arrow 1, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase; 2, glutathione synthetase; 3, methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase; 4, hypothetical protein; 5, methyltransferase; 6, probable fatty acid hydroxylase; 7, tRNA-Val-GAC; 8, hypothetical protein; 9, recombination associated protein; 10, Rhodanese-like domain protein; 11, hypothetical protein; P1, hypothetical protein; P2, phage-related tail protein; P3 (FN3523_1033), site-specific recombinase, phage integrase family; rtxD (FN3523_1034), membrane fusion protein (toxin secretion protein); rtxB (FN3523_1035), ABC-type toxin exporter; rtxA (FN3523_1036), RTX toxin; rtxC (FN3523_1037), RTX toxin activation protein; rtxA (FN3523_1038), vestigial RTX toxin gene. (B) RTX toxin locus of strain Fx1. Arrows 1 to 11 are as described for panel A. Arrow rtxA (FNFX1_0797), vestigial RTX toxin gene; rtxC (FNFX1_0799), RTX toxin activation protein; rtxA1 and rtxA2 (FNFX1_0800 and FNFX1_0801), RTX toxins; rtxB (FNFX1_0802), ABC-type toxin exporter; rtxD (FNFX1_0803 and FNFX1_0805), membrane fusion protein (toxin secretion protein, fragmented due to transposon insertion); hipBA (FNFX1_0806 and FNFX1_0807), persister cell locus; X1 and X2, hypothetical proteins; T1, IS1016 family transposase. (C) Arsenic resistance locus of strain U112. Arrows 1 to 11 are as described for panel A. Arrow rtxA (FTN_0793), vestigial RTX toxin gene; hipB (FTN_0795), repressor of hipA (absent from this strain); U1 (FTN_0792) and U2, hypothetical proteins; T2, ISFtu2 transposase; emrE (FTN_0799), multidrug resistance antiporter; arsRB (FTN_0800 and FTN_0801), arsenite resistance proteins.

The genomic analysis of strain Fx1 revealed a locus (12,973 bp, 32.6% GC) encoding proteins related to RTX toxins (Fig. 2B). The first ORF (FNFX1_0799, rtxC) had no homologs in the databases. Based on its location within the operon and predicted protein molecular mass (337 aa, 39 kDa), rtxC may encode a protein involved in fatty acylation during the activation of protoxin to cytotoxin. The second and third ORFs (FNFX1_0800 and FNFX1_0801, rtxA1and rtxA2, respectively) encoded putative proteins (1,234 and 1292 aa, 134.7 and 140 kDa, respectively) that are unrelated to α-hemolysin HlyA of E. coli but had 28 to 30% identity to the RTX cytotoxin-related proteins FrpA and FrpC of Neisseria meningitidis and the putative protein encoded by rtxA of strain 3523. Furthermore, the putative proteins encoded by rtxA1 and rtxA2 had 30% identity to each other. Interestingly, the rtx locus of strain Fx1 also contained rtxB and rtxD ORFs found in strain 3523. Whereas the rtxB ORFs (FNFX1_0802 and FN3523_1035) were 96% identical among the two strains, the rtxD ORF of strain Fx1 was fragmented due to a transposition event (FNFX1_0803 and FNFX1_0805). Within this region, strain Fx1 contained a gene encoding a hypothetical protein (FNFX1_0797, 141 aa) that had 86% identity to the putative RTX toxin (1,829 aa, encoded by rtxA) of strain 3523. An operon (1,487 bp; 31% GC) related to the hipBA locus of multidrug-tolerant bacteria also was found in this region (Fig. 2B), and putative HipA (FNFX1_0806, 418 aa) of strain Fx1 was 30% identical to the HipA persistence factor (2WIU_C, 446 aa) of E. coli. Genomes of several other F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains contained a similar hipBA operon, but strain U112 contained only a hipB ortholog (FTN_0795) and strain 3523 lacked hipBA.

Although the α-hemolysin of E. coli is the prototype of RTX toxins, genes encoding RTX toxins appear to be more common in pathogenic members of the Pasteurellaceae and are almost always associated with genes encoding a type I secretion system. The horizontal transfer of genes encoding RTX toxins across different bacterial families has been suggested based on phylogenetic analyses (23). The identification of a locus encoding putative RTX toxins in strains 3523 and Fx1 is especially intriguing, since such genes have not been reported thus far in any of the francisellae genomes. The bacteriocin ABC transporters of some bacteria have similarities to ABC transporters of type I secretion systems (99). Although bacteriocins of Francisella have been investigated previously and designated tularecins (1, 2, 5), very little is known about the genetic basis of their synthesis/secretion. The putative RTX toxin of strain 3523 is also related to the bacteriocins of Rhizobium leguminosarum and Nitrococcus mobilis Nb-231 (data not shown). Since the bacteriocin of R. leguminosarum has similarities to RTX toxins (63) and some cytolysins can function as bacteriocins (11), the putative RTX toxin of strain 3523 also may possess properties of bacteriocins and afford environmental fitness. The biochemical characterization of rtxCABD loci of strains 3523 and Fx1 is required to verify these hypotheses. Furthermore, the presence of a vestigial RTX toxin/bacteriocin-encoding ORF in several Francisella genomes, including strains 3523 (FN3523_1038), Fx1 (FNFX1_0797), and U112 (FTN_0793), indicates that the common ancestor of these bacteria was toxigenic/bacteriocinogenic. It is possible that the ancestral locus was truncated during habitat restriction and/or reductive evolution of these bacteria, and that it was reacquired by strains 3523 and Fx1 through horizontal transfer.

Arsenic resistance genes.

Arsenic is an environmental pollutant, and some microorganisms have evolved mechanisms of resistance to this cytotoxic agent. Arsenic exists in two oxidation states, arsenite [As(III)] and arsenate [As(V)], in biological systems. In most bacteria, the minimal arsenical resistance operon contains three ORFs (arsRBC), wherein the conversion of arsenate to arsenite is accomplished by a reductase (product of arsC), arsenite is transported out of the cell by a membrane-bound efflux pump (product of arsB), and arsR encodes an arsenic resistance regulatory protein. The plasmid- or transposon-mediated horizontal transfer of genes that confer arsenic resistance has been well documented (58). F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 contained a two-gene operon (1,218 bp, 30.4% GC) that encoded a putative transcriptional regulator and an arsenite exporter (arsRB) (Fig. 2C). At the protein level, strain U112 ArsB (FTN_0800, 342 aa) was 61% identical to the arsenite efflux transporter of Bacillus subtilis (BSU25790, 346 aa), and ArsR (FTN_0801, 116 aa) was 38% identical to the ArsR repressor of B. subtilis (BSU25810, 105 aa). A gene encoding a putative IS4 family transposase (247 aa) was found adjacent to the arsRB operon of strain U112. Within this region, strain U112 also contained a gene encoding a putative protein (FTN_0799, 109 aa) that was 44% identical to the small multidrug resistance antiporter EmrE of E. coli. The arsRB operon and homologs of emrE were present in F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain GA99-3548 and F. philomiragia strains ATCC 25015 and 25017, but not in strains 3523 and Fx1. In strain U112, the transposase gene associated with the arsRB operon was separated from an identical gene upstream by genes encoding a putative fatty acid hydroxylase (FTN_0797, 182 aa), an rRNA methyltransferase (FTN_0798, 718 aa), and a hipB gene. Adjacent to this transposase gene, strain U112 contained two ORFs encoding hypothetical proteins (FTN_0792 and FTN_0793, 140 and 189 aa, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Homologs of FTN_0792 were present in F. tularensis subsp. novicida strains GA99-3548 and GA99-3549 but not in strains 3523 and Fx1. Furthermore, FTN_0793 had 91% identity to the putative RTX toxin (1,829 aa, encoded by rtxA) of strain 3523. The occurrence of different loci (prophage region containing rtxCABD in strain 3523, transposon associated with rtxCABD in strain Fx1, and transposon associated with arsenite resistance genes in strain U112) flanked by conserved genes implies that this variable region is a genomic hot spot among different Francisella strains.

Polysaccharide biosynthesis gene clusters.

The LPS of Francisella spp. has several unique features and has been demonstrated to undergo antigenic variation (28). In contrast to F. tularensis subsp. tularensis, F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 expresses a single chemotype of LPS which has been proposed to contribute to virulence in a mouse model of infection (34). Immunobiological studies have demonstrated the activation of complement by pathogenic strains of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis as well as F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 and implicated their LPS O-antigen in mediating resistance to complement-mediated lysis (16). It also has been shown that mice immunized with LPS from strain U112 were protected against strain U112 but not against F. tularensis subsp. holarctica, and immunization with LPS from F. tularensis subsp. tularensis protected against F. tularensis subsp. holarctica but not against strain U112 (87). The wbt gene cluster of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain Schu S4 (17,378 bp, 31% GC) is involved in LPS biosynthesis and contained 15 ORFs (87). In contrast, a similar gene cluster of F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 (13,880 bp, 30.6% GC) contained only 12 ORFs (87). The LPS O antigens of F. tularensis subsp. novicida and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis have been shown to be structurally and immunologically distinct, due in part to the differences in wbt genes involved in their biosynthesis (73, 87).

Comparative genomic analyses revealed that strains 3523 and Fx1 contained a cluster of 21 (23,452 bp, 31% GC) and 16 (15,841 bp, 30.6% GC) ORFs, respectively, that were related to the wbt gene cluster of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain Schu S4. In addition, these strains contained conserved ORFs encoding proteins putatively involved in mannose modification adjacent to the wbt gene cluster (FN3523_1475 to FN3523_1476 and FNFX1_1451 to FNFX1_1452). Table S2 in the supplemental material contains a comprehensive list of the annotated ORFs found in the wbt gene clusters of these bacteria. The 10 strain-specific ORFs found in the wbt gene cluster of strain 3523 were organized into groups of five (FN3523_1480 to FN3523_1484, 4,575 bp, 29.6% GC), two (FN3523_1486 and FN3523_1487, 2,328 bp, 29.8% GC), and three (FN3523_1492 to FN3523_1494, 3,232 bp, 28.9% GC) contiguous ORFs. Of the six strain-specific ORFs found in the wbt gene cluster of strain Fx1, four were contiguous (FNFX1_1457 to FNFX1_1460, 3,888 bp, 28.6% GC). Of the five strain-specific ORFs found in the wbt gene cluster of strain Schu S4, four were contiguous (FTT_1452c to FTT_1455c, 4,150 bp, 30% GC). The wbt gene cluster of F. tularensis subsp. novicida strain U112 contained three noncontiguous ORFs that were strain specific (FTN_1422, FTN_1424, and FTN_1428). The wbt gene clusters of F. novicida-like strains 3523 and Fx1 contained four contiguous orthologous ORFs (FN3523_1488 to FN3523_1491, 4,175 bp, 30.7% GC, and FNFX1_1461 to FNFX1_1464, 4,204 bp, 30.6% GC, respectively) that had no homologs in strains U112 and Schu S4. The wbt gene clusters of strains U112 and Schu S4 contained three contiguous orthologous ORFs (FTN_1425 to FTN_1427, 3,380 bp, 32.5% GC, and FTT_1459c to FTT_1461c, 3,391 bp, 32.5% GC, respectively) that had no homologs in strains 3523 and Fx1.

The wbt gene clusters of strain Fx1 and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis Schu S4 contained two contiguous orthologous ORFs (FNFX1_1466 and FNFX1_1467, 1,225 bp, 32.7% GC, and FTT_1462c and FTT_1463c, 1,411 bp, 31% GC, respectively) that had no homologs in strains 3523 and U112. The wbt gene clusters of strains 3523 and U112 contained two contiguous orthologous ORFs (FN3523_1495 and FN3523_1496, 2,209 bp, 34% GC, and FTN_1429 and FTN_1430, 1,735 bp, 34.3% GC, respectively) that had no homologs in strains Fx1 and Schu S4. The strain-specific ORFs in these strains were flanked by highly conserved orthologous ORFs putatively encoding WbtM (FTT_1450c, FN3523_1477, and FNFX1_1453) and WbtA (FTT_1464c, FN3523_1497, FNFX1_1468, and FTN_1431). Furthermore, the wbt gene cluster of strain Schu S4 was flanked by genes encoding ISFtu1/IS630 transposases (126 aa each), and the wbt gene cluster of strain U112 contained a copy of ISFtu3/IS1016 (233 aa) that appears to have truncated the ORF encoding a putative dTDP-d-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (FTN_1420c; WbtM). However, the wbt gene clusters of strains 3523 and Fx1 lacked transposase genes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Since the wbt gene clusters of strains U112, Fx1, 3523, and Schu S4 display a cassette/mosaic structure with an outer conserved region and an inner variable region, it can be hypothesized that genes in the outer region encode functions common to all strains, whereas genes in the inner region encode serogroup-specific functions. If the number of genes in the inner variable region is an indicator of the complexity of LPS, then the LPS of strains 3523 and Fx1 likely is more different from that of strains U112 and Schu S4. A similar chimeric arrangement has been observed in the gene clusters encoding polysaccharide antigens in Salmonella enterica, and it has been proposed that genes in the outer conserved region mediate the conspecific exchange of genes in the inner variable region (44).

Biosynthesis of polysaccharides requires several glycosyltransferases (GTs), which catalyze the transfer of sugars from an activated donor to an acceptor molecule and are usually specific for the glycosidic linkages created (48). The genomes of strains U112, Fx1, 3523, and Schu S4 contained yet another cluster of 10 to 17 ORFs oriented in the same direction that encoded putative GTs and other proteins related to enzymes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis or cell wall/membrane biogenesis. This cluster has been tentatively designated psl (polysaccharide synthesis locus). Table S3 in the supplemental material contains a list of the annotated ORFs found within this gene cluster. Strain 3523 had 11 contiguous strain-specific ORFs (FN3523_1278 to FN3523_1288, 10,580 bp, 30.4% GC) within the psl cluster. Strain Fx1 had two contiguous strain-specific ORFs (FNFX1_1260 and FNFX1_1261, 1,897 bp, 26.8% GC) within the psl cluster. Strain Schu S4 had three contiguous strain-specific ORFs (FTT_0794 to FTT_0796, 2,675 bp, 27% GC) within the psl cluster. The psl clusters of strains Schu S4 and Fx1 contained two orthologous ORFs that were not found in strain 3523 (FTT_0797/FNFX1_1259 and FTT_0793/FNFX1_1262). These strain-specific ORFs were flanked by three contiguous orthologous ORFs at both ends. Furthermore, strain Fx1 contained a copy of the IS110 family transposase (FNFX1_1255; 315 aa) adjacent to the ORF that encoded a putative HAD family hydrolase (FNFX1_1256; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Based on gene content and organization, it may be surmised that the psl gene cluster was involved in LPS and/or exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis. Since the psl gene cluster of strain 3523 contained more genes than strains Fx1, U112, and Schu S4, it is possible that the LPS/EPS of this strain is more complex.

Thiamine biosynthesis genes.

Vitamin B1 (thiamine pyrophosphate) is involved in several microbial metabolic functions (74). Prokaryotes have evolved elaborate mechanisms to either synthesize this important cofactor de novo or acquire it from their niche (7). Thiamine biosynthesis in most bacteria is accomplished by two major pathways; one involves the formation of hydroxymethylpyrimidine pyrophospate (HMP-PP) from aminoimidazole ribotide using ThiC and ThiD, and the other involves the formation of hydroxyethylthiazole phosphate (HET-P) using ThiS, ThiF, ThiG, and ThiO. The enzyme thiamine phosphate synthase (ThiE) combines HMP-PP and HET-P to produce thiamine phosphate, which is phosphorylated by thiamine monophosphate kinase (ThiL) to produce thiamine pyrophosphate (7). The in vitro growth of most Francisella species is achieved by supplementing culture media with thiamine hydrochloride or thiamine pyrophosphate, indicating the absence of the thiamine biosynthesis (TBS) pathway in these bacteria (59).

Strain 3523 and F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017 contained an operon with six ORFs (thiCOSGDF; FN3523_1212 to FN3523_1217, 6,035 bp, 32% GC) encoding proteins related to enzymes involved in thiamine biosynthesis in several prokaryotes (Table 2). This gene cluster was not found in other Francisella genomes and was associated with a transposable element in F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017 (Fig. 3A). The genetic organization of the strain 3523 thiCOSGDF locus was similar to that of the plasmid-encoded thiCOGE locus involved in thiamine biosynthesis in Rhizobium etli (56). An analogous cluster (thiOGF) is found within plasmid pEA29 of the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora strain Ea88 (50). The chromosome of lithoautotrophic bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16 also contains a thiCOSGE locus that is proposed to be involved in the de novo synthesis of thiamine (68). At the protein level, strain 3523 ThiC was 68% identical to ThiC of R. etli (AAC45972) and R. eutropha (H16_A0235), whereas strain 3523 ThiF was 35% identical to ThiF of E. amylovora (NP_981993; E value, 3e−24). Furthermore, strain 3523 ThiO and ThiS were 27 and 31% identical to ThiO (H16_A0236) and ThiS (H16_A0237) of R. eutropha, respectively (E values, 9e−27 to 0.001). Putative thiazole synthase ThiG of strain 3523 was ∼50% identical to ThiG of R. etli (AAC45974; E value, 4e−66) and R. eutropha (H16_A0238; E value, 8e−77).

Table 2.

Strain 3523 genes involved in thiamine biosynthesis, glucuronate metabolism, and spermidine biosynthesis

| Locus tag and function | Protein size (aa) | Annotation | Closest homolog outside Francisella |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus tag | Protein size (aa) | % Identity | E value | |||

| Thiamine biosynthesis | ||||||

| FN3523_1212 | 251 | Thiazole biosynthesis adenylyltransferase (ThiF) | Mrub_1727 | 266 | 37 | 3e−39 |

| FN3523_1213 | 494 | Fused protein phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase (ThiD)/thiamine-phosphate pyrophosphorylase (ThiE) | lpg1568 | 495 | 36 | 9e−76 |

| FN3523_1214 | 259 | Thiazole synthase (ThiG) | lpg1567 | 263 | 59 | 2e−87 |

| FN3523_1215 | 66 | Thiamine biosynthesis protein (ThiS) | IL-0768 | 66 | 34 | 5e−05 |

| FN3523_1216 | 339 | Thiamine biosynthesis oxidoreductase (ThiO) | Kkor_0127 | 351 | 33 | 6e−44 |

| FN3523_1217 | 592 | Thiamine biosynthesis protein (ThiC) | CV_0235 | 632 | 72 | 0.0 |

| Glucuronate metabolism | ||||||

| FN3523_0892 | 325 | Inositol oxygenase | 56727 Miox | 285 | 38 | 7e−48 |

| FN3523_0893 | 462 | d-Xylose-proton symporter (XylT) | CBUD_1731 | 463 | 43 | 2e−91 |

| FN3523_0894 | 473 | Glucuronate isomerase (UxaC) | Sde_1272 | 471 | 51 | 2e−140 |

| FN3523_0895 | 182 | KDPG aldolase (KdgA) | BC1003_2949 | 213 | 37 | 5e−36 |

| FN3523_0896 | 306 | 2-Keto-3-deoxygluconate kinase (KdgK) | Sde_1269 | 296 | 43 | 1e−59 |

| FN3523_0897 | 396 | Mannonate dehydratase (UxuA) | PROSTU_04181 | 396 | 58 | 2e−134 |

| FN3523_0898 | 490 | d-Mannonate oxidoreductase (UxuB) | CJA_0180 | 492 | 43 | 2e−106 |

| FN3523_0899 | 774 | Alpha-glucosidase | BL00280 | 802 | 53 | 0.0 |

| FN3523_0900 | 486 | Rhamnogalacturonide transporter (RhiT) | KPK_1307 | 502 | 45 | 8e−116 |

| Spermidine biosynthesis | ||||||

| FN3523_0489 | 163 | S-Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SpeD) | Tcr_0272 | 167 | 66 | 3e−47 |

| FN3523_0490 | 289 | Spermidine synthase (SpeE) | Pfl01_1732 | 291 | 57 | 7e−97 |

| FN3523_0491 | 550 | Arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) | Avin_07050 | 636 | 31 | 8e−64 |

| FN3523_0492 | 328 | Agmatine deiminase (AguA) | Kkor_1127 | 327 | 51 | 5e−90 |

| FN3523_0493 | 286 | N-Carbamoylputrescine amidase (AguaB) | VP1774 | 288 | 57 | 4e−92 |

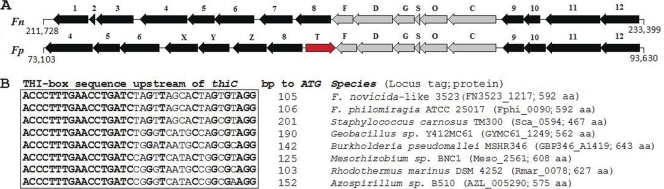

Fig. 3.

(A) Thiamine biosynthesis locus. Fn, F. novicida-like strain 3523; Fp, F. philomiragia ATCC 25017. Arrow 1, metabolite:H+ symporter (MHS) family protein; 2, hypothetical protein; 3, exodeoxyribonuclease VII large subunit; 4, transglutaminase-like superfamily protein; 5, conserved hypothetical protein; 6, conserved hypothetical protein; 7, hypothetical protein; 8, major facilitator superfamily transporter; 9, glutamate racemase; 10, hypothetical protein; 11, excinuclease B subunit; 12, exodeoxyribonuclease; COSGDF (FN3523_1212 to FN3523_1217), thiamine biosynthesis proteins; T, transposase; X, hypothetical protein; Y, hypothetical protein; Z, major facilitator transporter. (B) Putative thiamine regulatory element. A conserved 36-bp sequence upstream of thiC from eight species is boxed. Nucleotides identical in all eight sequences are shown in boldface. The length of sequence between the THI box and the start codon of thiC in each species is indicated (bp to ATG). The locus tag and the number of amino acids encoded by thiC in each species are shown in parentheses.

In strain 3523, FN3523_1213 appeared to encode a putative fused protein containing hydroxy-phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase and thiamine-phosphate pyrophosphorylase domains. In some bacteria, these functions are encoded by two different ORFs (thiD and thiE, respectively). Homologs of FN3523_1213 were found in several bacteria (e.g., Legionella pneumophila, Coxiella burnetii, Geobacter sulfurreducens, and Colwellia psychrerythraea; ∼30% protein identity) and plants (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, Zea mays, and Brassica napus; ∼29% protein identity). It has been proposed that these bifunctional enzymes are involved in the synthesis of HMP-PP as well as the condensation of HMP-PP and HET-P to produce thiamine monophosphate (36, 72, 74). The 5′ untranslated regions of operons involved in thiamine biosynthesis and transport have been shown to contain a regulatory element called the THI box sequence (55). Based on the alignment of conserved sequences upstream of operons involved in thiamine biosynthesis from various bacteria, a putative THI box sequence was identified upstream of thiC in strain 3523 and F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017 (Fig. 3B). The identification of a putative THI box upstream of thiC in strain 3523 suggests a thiamine-dependent regulation of this gene, similarly to other bacteria that have TBS genes (74).

In bacteria that lack a TBS pathway, thiamine kinases may facilitate the salvage of dephosphorylated thiamine intermediates from the environment or growth medium (32). A gene that encodes a putative thiamine pyrophosphokinase (TPK) was found in most members of Francisella, including strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 (FN3523_0611, FNFX1_0669, and FTN_0662, respectively). F. novicida strain U112 TPK was 27% identical to Bacillus subtilis TPK (THIN_BACSU; E value, 3e−10), which catalyzes the direct conversion of thiamine to thiamine pyrophosphate (52). In Listeria monocytogenes, which has an incomplete thiamine biosynthesis pathway, it has been shown that proliferation within host cells is reduced upon the deletion of thiD and thiT, encoding an HMP salvage protein and a thiamine transporter, respectively (77). In addition, strains of E. amylovora that lack the thiOSGF operon-containing plasmid pEA29 have been shown to be altered in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and less virulent (51). Aspergillus nidulans, the filamentous ascomycete which induces a fatal systemic mycosis in mice, has been shown to be less pathogenic when its thiamine biosynthetic pathway was blocked by mutation (70). It also has been suggested that Brucella abortus and R. etli, which have similar intracellular lifestyles, require increased thiamine in the stationary phase (56, 76). In view of these observations, the TBS gene cluster of strain 3523 could serve to enhance its survival in the environment/host and also may have an indirect role in pathogenesis. Furthermore, the TBS genes of strain 3523 could be useful in accelerating the growth of thiamine auxotrophs of F. tularensis in the laboratory.

Glucuronate metabolism genes.

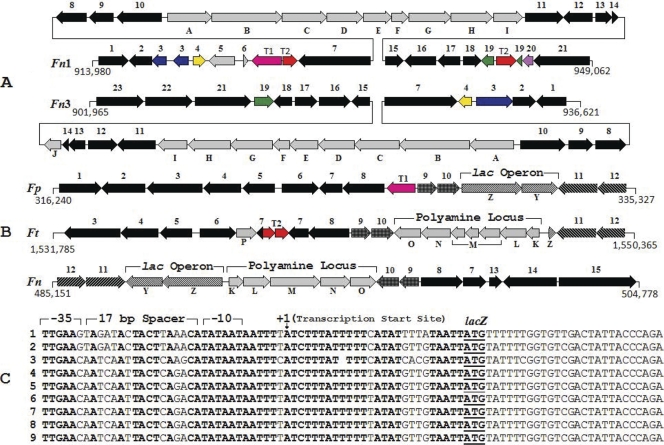

Some bacteria have evolved mechanisms for the metabolism of uronic acids and uronates using the Entner-Doudoroff pathway (65). In this pathway, α-d-glucuronic acid (GlcUA) is converted into 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate (KDG) by a three-step process. The subsequent phosphorylation of KDG yields 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate (KDPG), which is finally cleaved to produce glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) and pyruvate. Comparative genomic analyses indicated that strains 3523 and Fx1 contained a cluster of nine ORFs that appear to constitute a polycistronic operon (FN3523_0892 to FN3523_0900 and FNFX1_0904 to FNFX1_0912, respectively, 11,784 bp, 31.7% GC). These ORFs encoded putative proteins related to enzymes involved in GlcUA catabolism (Table 2). Furthermore, genes encoding putative transposases of IS1106 and IS1016 families were found near the GlcUA utilization gene cluster of strain Fx1 but not in strain 3523 (Fig. 4A). This gene cluster was not found in other Francisella genomes, with the exception of F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25015, which appeared to contain the entire cluster (79 to 89% identity at the protein level).

Fig. 4.

(A) Glucuronate metabolism locus. Fn1, F. novicida-like strain Fx1; Fn3, F. novicida-like strain 3523. Arrow 1, hypothetical protein; 2, zinc-iron permease family protein; 3, cobalamin synthesis protein (putative GTPase); 4, zinc-iron uptake regulatory protein; 5, RNase T2 family protein; 6, hypothetical protein; 7, phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase beta chain; 8, phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase alpha chain; 9, drug/metabolite transporter superfamily protein; 10, putative transporter; 11, sugar transporter; 12, conserved hypothetical protein; 13, hypothetical protein; 14, transcriptional regulator; 15, hypothetical protein; 16, Holliday junction DNA helicase RuvB; 17, short-chain dehydrogenase family protein FabG; 18, CBS domain pair protein; 19, GDSL-like lipolytic enzyme; 20, hypothetical protein; 21, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase; 22, GMP synthase; 23, amino acid permease; ABCDEFGHI (FNFX1_0904 to FNFX1_0912, FN3523_0892 to FN3523_0900), glucuronate metabolism genes; J, hypothetical protein; T1, IS1106 transposase; T2, IS1016 transposase. (B) Lactose and polyamine metabolism loci. Fp, F. philomiragia ATCC 25017; Ft, Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis WY96-3418; Fn, F. novicida-like strain 3523. Arrow 1, glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase; 2, peptide transporter; 3, ABC transporter ATP-binding protein; 4, tetracycline efflux protein TetA; 5, conserved domain protein; 6, drug:H+ antiporter-1 (DHA1) family protein; 7, 23S rRNA (guanosine-2′-O)-methyltransferase (RlmB); 8, UDP-N-acetylmuramate:l-alanyl-gamma-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelate ligase; 9, orotate phosphoribosyltransferase; 10, UDP-2;3-diacylglucosamine hydrolase; 11, threonine synthase; 12, homoserine kinase; 13, hypothetical protein; 14, arginyl-tRNA synthetase; 15, organic solvent tolerance protein; Y (FN3523_0487), sugar permease; Z (FN3523_0488), beta-galactosidase; K (FN3523_0489), S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase; L (FN3523_0490), spermidine synthase; M (FN3523_0491), biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase; N (FN3523_0492), agmatine deiminase; O (FN3523_0493), N-carbamoylputrescine amidase; P, hypothetical protein; T1, transposase/integrase-like protein; T2, ISFtu1 transposase fragments. (C) Presumptive lac promoter of Francisella. A conserved 61-bp sequence upstream of the lacZ ORF from nine strains of Francisella is depicted. Nucleotides identical in all nine sequences are shown in boldface. The −10 (TATAAT), −35 (TTGAAC or TTGAAG), and 17-bp spacer regions are indicated. An arrow points to the putative transcription start site (+1). The predicted start codon of lacZ is underlined. Sequences 4 through 9 are identical. Row 1, F. philomiragia ATCC 25017; 2, F. novicida-like strain Fx1; 3, F. novicida-like strain 3523; 4, F. tularensis FSC198; 5, F. tularensis WY96-3418; 6, F. tularensis FSC147; 7, F. tularensis OSU18; 8, F. tularensis FTNF002-00; 9, F. tularensis LVS.

The predicted mannonate dehydratase, 2-keto-3-deoxygluconokinase, KDPG aldolase, and glucuronate isomerase proteins from strain 3523 had 57, 37, 37, and 28% identities to E. coli UxuA (ECs5281), KdgK (ECs4406), KdgA (ECs2560), and UxaC (ECs3974), respectively (E values, 5e−132 to 9e−26). These enzymes catalyze the dehydration of d-mannonate to KDG, phosphorylation of KDG, cleavage of KDPG to pyruvate and G3P, and the conversion of d-glucuronate to d-fructuronate, respectively (65). The GlcUA utilization gene clusters of strains 3523 and Fx1 had some similarities to that of Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6, which has been predicted to metabolize GlcUA akin to E. coli and Bacillus subtilis (79). Furthermore, one end of the GlcUA utilization gene cluster of B. stearothermophilus T-6 also contains an ORF encoding a protein that has similarities to transposases of the IS481 family (49), indicating the possible horizontal transfer of this locus.

The ORFs encoding a putative inositol oxygenase in strains 3523, Fx1, and ATCC 25015 had no bacterial homologs in the public databases outside the genus Francisella. However, strain 3523 inositol oxygenase had 38% identity to Mus musculus myo-inositol oxygenase (56727 Miox; E value, 7e−48), which catalyzes the conversion of myo-inositol to GlcUA (9). myo-Inositol and its derivatives are ubiquitous among eukaryotes and archaea, but their synthesis and metabolism is believed to be less common among bacteria (54). Although none of the francisellae genomes sequenced to date contained ORFs encoding proteins putatively involved in the transport and/or metabolism of myo-inositol, most of them, including strains 3523 and Fx1, had a suhB homolog (FN3523_1410 and FNFX1_1384, respectively). This evolutionarily conserved gene encoded inositol-1-monophosphatase, which hydrolyzes myo-inositol-1-phosphate to yield free myo-inositol (60, 61). Thus, it appears that most members of Francisella can convert myo-inositol-1-phosphate to free myo-inositol. However, only strains 3523 and Fx1 as well as F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25015 are able to utilize myo-inositol to synthesize GlcUA, which then is metabolized using the Entner-Doudoroff pathway.

Polyamine biosynthesis and transport genes.

Polycations such as putrescine and spermidine are precursors for several cellular components, and pathways for the biosynthesis of these polyamines have been described in a number of species (97). Polyamines also have been implicated in bacterial oxidative stress response and virulence (78). The ubiquitous presence of genes encoding putrescine transport systems (potFGHI) in bacterial genomes suggests that these small molecules play crucial roles in cellular physiology. Strains 3523, Fx1, and U112 as well as F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains Schu S4, WY96-3418, and OSU18 contained a cadA gene (FN3523_0462, FNFX1_0489, FTN_0504, FTT_0406, FTW_1667, and FTH_0474, respectively). This gene encoded a putative protein that had 55% identity to E. coli lysine decarboxylase (NP_418555; E value, 0), which is involved in cadaverine biosynthesis (53). The strains mentioned above also contained a potGHI operon (e.g., FN3523_1141 to FN3523_1143) and an unlinked potF gene (e.g., FN3523_0514).

Furthermore, strain 3523 contained a cluster of five ORFs (FN3523_0489 to _0493, 4,873 bp, 32.6% GC) encoding putative proteins related to enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of spermidine and putrescine (Table 2, Fig. 4B). This gene cluster was not found in strains Fx1 and U112 but was present in other F. tularensis subsp. tularensis genomes (e.g., strains Schu S4, OSU18, and FSC147). In F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain WY96-3418, fragmented ISFtu1 elements were found near this gene cluster (Fig. 4B). Strain 3523 S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase had 45% identity to SpeD (MJ_0315; E value, 9e−27) of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, but it is unrelated to SpeD of E. coli. Strain 3523 spermidine synthase and arginine decarboxylase had 55 and 28% identities to E. coli SpeE (3O4F_A; E value, 1e−92) and SpeA (3NZQ_B; E value, 3e−60), respectively. Strain 3523 agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase had 37 and 57% identities to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 AguA (PA0292; E value, 1e−58) and AguB (PA0293; E value, 8e−94), respectively. These proteins are key components in the biosynthesis of polyamines in M. jannaschii, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa (14, 35, 45). The acquisition of genes encoding polyamine biosynthesis/metabolism functions may enhance the adaptive capabilities of a bacterium (78, 97). The presence of spermidine biosynthesis genes in strain 3523 as well as F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains, but their absence in strains Fx1, U112, and F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017, is a notable feature from a pathogenic and evolutionary standpoint.

Lactose metabolism genes.

The lac operon, which contains the structural genes encoding proteins that facilitate lactose metabolism, is found in a variety of bacteria. Lactose is imported into the cell as a free sugar by means of a permease, and the enzyme β-galactosidase hydrolyzes this disaccharide into galactose and glucose (96). Genome comparisons revealed that strain 3523 contained a cluster of two ORFs (3,165 bp, 32% GC) adjacent to the spermidine biosynthesis locus that appear to constitute an operon (FN3523_0487 to FN3523_0488) (Fig. 4B). The predicted LacZ of strain 3523 had 29% identity to the β-galactosidase (AAF16519, BgaB; E value, 2e−79) of Carnobacterium maltaromaticum (17) and 26% identity to the β-galactosidase (O07012.2, GanA; E value, 8e−76) of Bacillus subtilis (19), but it is unrelated to the β-galactosidase of E. coli. Strain 3523 LacY had 25% identity to the putative oligogalacturonide transporter (NP_752266; E value, 3e−07) of E. coli CFT073 and 22% identity to the putative sugar transporter (YP_081973; E value, 1e−08) of Bacillus cereus. A similar lac operon was found in strain Fx1 and F. philomiragia strains ATCC 25015 and 25017. However, genes encoding the galactoside O-acetyltransferase (lacA) and the regulatory protein (lacI) were not found in any of these bacteria. In F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017, an ORF encoding a putative transposase/integrase-like protein was found near the lac operon (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, other F. tularensis subsp. tularensis genomes (e.g., strains Schu S4, WY96-3418, OSU18, and FSC147) contained a truncated lacZ. Based on the alignment of conserved sequences upstream of lacZ from nine different Francisella genomes, a putative lac promoter also was identified (Fig. 4C). This promoter had high AT content (78 to 86%) and was similar to the lac promoters of several Gram-negative bacteria.

Although the classic lac operon of E. coli consists of three ORFs (lacZYA), which are regulated by the product of the adjacent lacI repressor gene, bacteria containing only lacZY or lacZ have been identified (27, 43, 83). While the evolutionary origin of the E. coli lac operon is uncertain (83), the occurrence of lac genes near integrative and conjugative elements and the identification of E. coli-like lac operons in some Gram-positive bacteria suggest their lateral mobility (18, 26, 89). From genome comparisons, it appeared that the last common lactose-utilizing ancestor of strains Fx1 and 3523, F. philomiragia strain ATCC 25017, and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains have acquired the lacZY operon by transposon-mediated horizontal transfer. The loss of this operon in strain U112 and most F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains may be due to niche selection or through genetic drift, and a similar mechanism for some members of Enterobacteriaceae has been proposed (83). The ability to metabolize lactose probably affords strains Fx1 and 3523 a growth advantage in environments where the sugar is present, and these may represent a subset of Francisella species that have retained an ancestral copy of the lac operon. Although detailed phylogenetic analyses are required to establish the evolutionary origin of the Francisella lac operon, the lacZ gene and its promoter identified in this study should be useful in genetic studies requiring a reporter/marker within this group of bacteria.

Summary of important genetic traits and phylogenetic analyses.

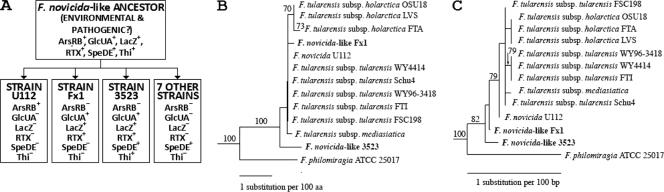

Based on whole-genome comparisons of different Francisella species and strains, the following genetic acquisitions and losses are evident. While strain Fx1 contained the lac operon in addition to genes for GlcUA utilization, strain 3523 contained the lac operon along with GlcUA utilization, thiamine biosynthesis, and spermidine biosynthesis genes. Whereas most F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains had lost loci for GlcUA utilization and thiamine biosynthesis, they contained a vestigial lacZ gene and a complete speDE system. Furthermore, strains 3523 and Fx1 were the only ones containing the loci for RTX toxin production. Notably, strain U112 lacked all of these loci but contained an arsRB operon, which was absent from strains 3523 and Fx1 as well as F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains. A summary of the presence/absence of these loci is presented in Fig. 5A. It is possible that strain U112, an environmental isolate of F. tularensis subsp. novicida, had retained an arsRB operon but had lost loci for lactose and GlcUA utilization as well as genes for thiamine biosynthesis because of niche selection. Strains 3523 and Fx1 appeared to be in transition from being environmental to pathogenic, since they have lost the arsRB operon but contain loci for lactose and GlcUA utilization, in addition to genes for RTX toxin production. Extant strains of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis appeared to have lost the arsRB operon and loci for lactose and GlcUA utilization, in addition to genes for thiamine biosynthesis, as a consequence of host adaptation and reductive evolution. Since strain 3523 and most F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains contain a complete speDE system, the role of spermidine in the pathogenesis of tularemia needs to be carefully studied. This is especially important in light of recent reports implicating spermine and spermidine in the stimulation of host cells by F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (10).

Fig. 5.

(A) Summary of important genetic traits among strains U112, Fx1, 3523, and seven other Francisella isolates (strains FSC198, Schu S4, WY96-3418, LVS, FTA, OSU18, and FSC147). ArsRB, arsenic resistance locus; GlcUA, glucuronate metabolism locus; LacZ, lactose metabolism locus; RTX, RTX toxin locus; SpeDE, spermidine biosynthetic locus; Thi, thiamine biosynthesis locus. A plus indicates the presence and a minus indicates the absence of a particular locus in each strain. (B) Neighbor-joining tree using succinate dehydrogenase (sdhA) genes showing phylogenetic relationships among strains U112, Fx1, 3523, and 11 other Francisella isolates for which complete genomes are available. Nodes with bootstrap support greater than 70% are indicated. (C) A neighbor-joining tree like that in panel B is shown, but full-length 16S rRNA genes were used.

Based on these observations, it may be surmised that the genes/loci for arsenite resistance, GlcUA utilization, lactose utilization, and thiamine biosynthesis are more ancient. It is possible that genes for RTX toxin production and spermidine biosynthesis were acquired later by an F. tularensis/novicida-like clade. Although strains 3523 and Fx1 were isolated in different parts of the globe, both were associated with marine environments, and their recent common ancestry cannot be ruled out. Deletion-based phylogenetic analyses have indicated F. tularensis subsp. novicida to be the oldest and that both the acquisition and loss of genes have occurred during the evolution of F. tularensis (84). Phylogenetic analyses based on full-length 16S rRNA and sdhA genes support the proposition that F. tularensis subsp. novicida is very closely related to F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and indicate that strain 3523 represents a new lineage parental to the other F. tularensis subsp. novicida and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains (Fig. 5B and C).

In conclusion, previous genome comparisons have indicated that subspecies of F. tularensis have independently and intermittently acquired and lost genes, and that the net loss in F. tularensis subsp. tularensis is more than the net loss in F. tularensis subsp. novicida (4, 75). Based on the analyses of unidirectional genomic deletion events and single-nucleotide variations, it has been suggested that the different subspecies of F. tularensis have evolved by vertical descent (84). Analyses of the genomes of strains 3523 and Fx1 imply that these strains represent new links in the chain of evolution from the F. novicida-like ancestor to the extant strains of F. tularensis. The presence of genes encoding novel biochemical properties appeared to have contributed to the metabolic enrichment and niche expansion of F. novicida-like strains. The inability to acquire new genes coupled with the loss of ancestral traits and the consequent reductive evolution may be a cause for, and an effect of, niche restriction of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis. Although numerous previous studies have discovered the genetic basis for some of the biochemical and antigenic dissimilarities between F. tularensis subsp. novicida and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains, comparative genome sequence analyses have provided a comprehensive account of innate and acquired genetic traits in this important group of bacteria.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the United States Department of Homeland Security (Chemical and Biological Division, Science and Technology Directorate) through an interagency agreement (grant number HSHQDC-08-X-00790) and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We thank Karen Davenport, Christine Munk, and other members of the Genome Sequencing and Finishing Team at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for help with sequencing strains Fx1 and 3523.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aikimbaev M. A., Kunitsa G. M., Chimirov O. B. 1980. Method of detecting bacteriocins in the agent of tularemia. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1980:43–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aikimbayev A. M., Kunitsa T. N., Temiraliyeva G. A., Atshabar B. A., Lukhnova L. Y. 2002. The characteristic of the Francisella tularensis Mediaasiatica, p. 106, abstr. 112. International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aziz R. K., et al. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barabote R. D., et al. 2009. Complete genome sequence of Francisella tularensis subspecies holarctica FTNF002-00. PLoS One 4:e7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basilova G. I., Nekrasov A. A., Pilipenko V. G. 1983. Culture properties of the causative agent of tularemia isolated in natural foci in Stavropol Territory, the Kalmyk ASSR and the Armenian SSR. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1983:40–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beckstrom-Sternberg S., et al. 2007. Complete genomic characterization of a pathogenic A.II strain of Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis. PLoS One 2:e947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Begley T. P., et al. 1999. Thiamin biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Arch. Microbiol. 171:293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Birdsell D. N., et al. 2009. Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida isolated from a human in Arizona. BMC Res. Notes 2:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown P. M., et al. 2006. Purification, crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of mouse myo-inositol oxygenase. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 62:811–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carlson P. E., Jr., et al. 2009. Global transcriptional response to spermine, a component of the intramacrophage environment, reveals regulation of Francisella gene expression through insertion sequence elements. J. Bacteriol. 191:6855–6864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carniol K., Gilmore M. S. 2006. Enterococcus faecalis cytolysis toxin, p. 717–727. In Alouf J. E., Popoff M. R. (ed.),The comprehensive sourcebook of bacterial protein toxins, 3rd ed. Academic Press, Elsevier Ltd., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Champion M. D., et al. 2009. Comparative genomic characterization of Francisella tularensis strains belonging to low and high virulence subspecies. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaudhuri R. R., et al. 2007. Genome sequencing shows that European isolates of Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis are almost identical to US laboratory strain Schu S4. PLoS One 2:e352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou H. T., Kwon D. H., Hegazy M., Lu C. D. 2008. Transcriptome analysis of agmatine and putrescine catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 190:1966–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clarridge J. E., III, et al. 1996. Characterization of two unusual clinically significant Francisella strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1995–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clay C. D., Soni S., Gunn J. S., Schlesinger L. S. 2008. Evasion of complement-mediated lysis and complement C3 deposition are regulated by Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide O antigen. J. Immunol. 181:5568–5578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coombs J. M., Brenchley J. E. 1999. Biochemical and phylogenetic analyses of a cold-active beta-galactosidase from the lactic acid bacterium Carnobacterium piscicola BA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5443–5450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cornelis G. 1981. Sequence relationships between plasmids carrying genes for lactose utilization. J. Gen. Microbiol. 124:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daniel R. A., Haiech J., Denizot F., Errington J. 1997. Isolation and characterization of the lacA gene encoding beta-galactosidase in Bacillus subtilis and a regulator gene, lacR. J. Bacteriol. 179:5636–5638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dereeper A., et al. 2008. Phylogeny fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W465–W469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edgar R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Escudero R., et al. 2008. Molecular method for discrimination between Francisella tularensis and Francisella-like endosymbionts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3139–3143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frey J., Kuhnert P. 2002. RTX toxins in Pasteurellaceae. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gallagher L. A., et al. 2007. A comprehensive transposon mutant library of Francisella novicida, a bioweapon surrogate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1009–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gil H., et al. 2006. Deletion of TolC orthologs in Francisella tularensis identifies roles in multidrug resistance and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12897–12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gilbert H. J., Hall J. 1987. Molecular cloning of Streptococcus bovis lactose catabolic genes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:2285–2293 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guiso N., Ullmann A. 1976. Expression and regulation of lactose genes carried by plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 127:691–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gunn J. S., Ernst R. K. 2007. The structure and function of Francisella lipopolysaccharide. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105:202–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hanekop N., Zaitseva J., Jenewein S., Holland I. B., Schmitt L. 2006. Molecular insights into the mechanism of ATP-hydrolysis by the NBD of the ABC-transporter HlyB. FEBS Lett. 580:1036–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hollis D. G., et al. 1989. Francisella philomiragia comb. nov. (formerly Yersinia philomiragia) and Francisella tularensis biogroup novicida (formerly Francisella novicida) associated with human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1601–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huber B., et al. Description of Francisella hispaniensis sp. nov., isolated from human blood, reclassification of Francisella novicida (Larson et al. 1955) Olsufiev et al. 1959 as Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida comb. nov. and emended description of the genus Francisella. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60::1887–1896. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.015941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jurgenson C. T., Begley T. P., Ealick S. E. 2009. The structural and biochemical foundations of thiamin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:569–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karlsson J., et al. 2000. Sequencing of the Francisella tularensis strain Schu 4 genome reveals the shikimate and purine metabolic pathways, targets for the construction of a rationally attenuated auxotrophic vaccine. Microb. Comp. Genomics 5:25–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kieffer T. L., Cowley S., Nano F. E., Elkins K. L. 2003. Francisella novicida LPS has greater immunobiological activity in mice than F. tularensis LPS, and contributes to F. novicida murine pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 5:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim A. D., Graham D. E., Seeholzer S. H., Markham G. D. 2000. S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase from the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii: identification of a novel family of pyruvoyl enzymes. J. Bacteriol. 182:6667–6672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim Y. S., et al. 1998. A Brassica cDNA clone encoding a bifunctional hydroxymethylpyrimidine kinase/thiamin-phosphate pyrophosphorylase involved in thiamin biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 37:955–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kiss K., Liu W., Huntley J. F., Norgard M. V., Hansen E. J. 2008. Characterization of fig operon mutants of Francisella novicida U112. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 285:270–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langille M. G., Hsiao W. W., Brinkman F. S. 2008. Evaluation of genomic island predictors using a comparative genomics approach. BMC Bioinformatics 9:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larson C. L., Wicht W., Jellison W. L. 1955. A new organism resembling P. tularensis isolated from water. Public Health Rep. 70:253–258 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Larsson P., et al. 2009. Molecular evolutionary consequences of niche restriction in Francisella tularensis, a facultative intracellular pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larsson P., et al. 2005. The complete genome sequence of Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia. Nat. Genet. 37:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leelaporn A., Yongyod S., Limsrivanichakorn S., Yungyuen T., Kiratisin P. 2008. Francisella novicida bacteremia, Thailand. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1935–1937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leong-Morgenthaler P., Zwahlen M. C., Hottinger H. 1991. Lactose metabolism in Lactobacillus bulgaricus: analysis of the primary structure and expression of the genes involved. J. Bacteriol. 173:1951–1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li Q., Reeves P. R. 2000. Genetic variation of dTDP-l-rhamnose pathway genes in Salmonella enterica. Microbiology 146:2291–2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li Y. F., Hess S., Pannell L. K., White Tabor C., Tabor H. 2001. In vivo mechanism-based inactivation of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylases from Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:10578–10583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lin W., et al. 1999. Identification of a Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin gene cluster that is tightly linked to the cholera toxin prophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lindgren H., et al. 2009. The 58-kilodalton major virulence factor of Francisella tularensis is required for efficient utilization of iron. Infect. Immun. 77:4429–4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lundborg M., Modhukur V., Widmalm G. 2010. Glycosyltransferase functions of E. coli O-antigens. Glycobiology 20:366–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mahillon J. 2002. Insertion sequence elements and transposons in Bacillus, p. 236–253. In Berkeley R., Heyndrickx M., Logan N., de Vos P. (ed.), Applications and systematics of Bacillus and relatives. Blackwell Science, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 50. McGhee G. C., Jones A. L. 2000. Complete nucleotide sequence of ubiquitous plasmid pEA29 from Erwinia amylovora strain Ea88: gene organization and intraspecies variation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4897–4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McGhee G. C., Sundin G. W. 2008. Thiamin biosynthesis and its influence on exopolysaccharide production: a new component of virulence identified on Erwinia amylovora plasmid pEA29. Acta Hortic. (ISHS) 793:271–277 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Melnick J., et al. 2004. Identification of the two missing bacterial genes involved in thiamine salvage: thiamine pyrophosphokinase and thiamine kinase. J. Bacteriol. 186:3660–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meng S. Y., Bennett G. N. 1992. Regulation of the Escherichia coli cad operon: location of a site required for acid induction. J. Bacteriol. 174:2670–2678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Michell R. H. 2008. Inositol derivatives: evolution and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miranda-Ríos J. 2007. The THI-box riboswitch, or how RNA binds thiamin pyrophosphate. Structure 15:259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miranda-Ríos J., et al. 1997. Expression of thiamin biosynthetic genes (thiCOGE) and production of symbiotic terminal oxidase cbb3 in Rhizobium etli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6887–6893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Molins C. R., Carlson J. K., Coombs J., Petersen J. M. 2009. Identification of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis A1 and A2 infections by real-time PCR. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 64:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mukhopadhyay R., Rosen B. P., Phung L. T., Silver S. 2002. Microbial arsenic: from geocycles to genes and enzymes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:311–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nagle S. C., Jr., Anderson R. E., Gary N. D. 1960. Chemically defined medium for the growth of Pasteurella tularensis. J. Bacteriol. 79:566–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Neuwald A. F., York J. D., Majerus P. W. 1991. Diverse proteins homologous to inositol monophosphatase. FEBS Lett. 294:16–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nigou J., Dover L. G., Besra G. S. 2002. Purification and biochemical characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis SuhB, an inositol monophosphatase involved in inositol biosynthesis. Biochemistry 41:4392–4398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Olsufiev N. G., Emelyanova O. S., Dunayeva T. N. 1959. Comparative study of strains of B. tularense in the old and new world and their taxonomy. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 3:138–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oresnik I. J., Twelker S., Hynes M. F. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a Rhizobium leguminosarum gene encoding a bacteriocin with similarities to RTX toxins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2833–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Owen C. R., Buker E. O., Jellison W. L., Lackman D. B., Bell J. F. 1964. Comparative studies of Francisella tularensis and Francisella novicida. J. Bacteriol. 87:676–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peekhaus N., Conway T. 1998. What's for dinner? Entner-Doudoroff metabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:3495–3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Petersen J. M., et al. 2009. Direct isolation of Francisella spp. from environmental samples. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48:663–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pimenta A. L., Racher K., Jamieson L., Blight M. A., Holland I. B. 2005. Mutations in HlyD, part of the type 1 translocator for hemolysin secretion, affect the folding of the secreted toxin. J. Bacteriol. 187:7471–7480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pohlmann A., et al. 2006. Genome sequence of the bioplastic-producing “Knallgas” bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1257–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Prochazka O., Dubanska H. 1972. The antigenic structure of Francisella tularensis. I. Isolation of the ether antigen and its fractionation. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 17:232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Purnell D. M. 1978. Virulence genetics of Aspergillus nidulans Eidam: a review. Mycopathologia 65:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ramakrishnan G., Meeker A., Dragulev B. 2008. fslE is necessary for siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in Francisella tularensis Schu S4. J. Bacteriol. 190:5353–5361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rapala-Kozik M., Olczak M., Ostrowska K., Starosta A., Kozik A. 2007. Molecular characterization of the thi3 gene involved in thiamine biosynthesis in Zea mays: cDNA sequence and enzymatic and structural properties of the recombinant bifunctional protein with 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine (phosphate) kinase and thiamine monophosphate synthase activities. Biochem. J. 408:149–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Raynaud C., et al. 2007. Role of the wbt locus of Francisella tularensis in lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biogenesis and pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 75:536–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rodionov D. A., Vitreschak A. G., Mironov A. A., Gelfand M. S. 2002. Comparative genomics of thiamin biosynthesis in procaryotes. New genes and regulatory mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48949–48959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rohmer L., et al. 2007. Comparison of Francisella tularensis genomes reveals evolutionary events associated with the emergence of human pathogenic strains. Genome Biol. 8:R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Roop R. M., Jr., et al. 2003. Brucella stationary-phase gene expression and virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:57–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schauer K., Stolz J., Scherer S., Fuchs T. M. 2009. Both thiamine uptake and biosynthesis of thiamine precursors are required for intracellular replication of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 191:2218–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shah P., Swiatlo E. 2008. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 68:4–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shulami S., Gat O., Sonenshein A. L., Shoham Y. 1999. The glucuronic acid utilization gene cluster from Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6. J. Bacteriol. 181:3695–3704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]