Abstract

Helicobacter pylori persistently colonizes humans, causing gastritis, ulcers, and gastric cancer. Adherence to the gastric epithelium has been shown to enhance inflammation, yet only a few H. pylori adhesins have been paired with targets in host tissue. The alpAB locus has been reported to encode adhesins involved in adherence to human gastric tissue. We report that abrogation of H. pylori AlpA and AlpB reduces binding of H. pylori to laminin while expression of plasmid-borne alpA or alpB confers laminin-binding ability to Escherichia coli. An H. pylori strain lacking only AlpB is also deficient in laminin binding. Thus, we conclude that both AlpA and AlpB contribute to H. pylori laminin binding. Contrary to expectations, the H. pylori SS1 mutant deficient in AlpA and AlpB causes more severe inflammation than the isogenic wild-type strain in gerbils. Identification of laminin as the target of AlpA and AlpB will facilitate future investigations of host-pathogen interactions occurring during H. pylori infection.

INTRODUCTION

The gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori can persist in the gastric milieu for decades by using a variety of strategies to evade gastric acid, gastric emptying, and innate and acquired immune responses. H. pylori was once believed to reside solely in the superficial epithelium; however, mounting evidence suggests that H. pylori also infiltrates deeper regions of gastric tissue, including the lamina propria and capillaries (2, 25, 34, 41). Improved detection methods have revealed organisms in the lamina propria and gastric lymph nodes and even adhering to red blood cells within capillaries (2, 14, 25, 48). H. pylori is able to disrupt tight junctions and invade intercellular spaces (2, 41).

H. pylori adherence has therefore been the focus of many studies (55). A number of studies have characterized binding of H. pylori to gastric mucin (24, 29, 58). Adhesins with known ligands include SabA, BabA, and HpaA. SabA, a sialic acid-binding adhesin, functions as a hemagglutinin and has been associated with higher colonization density in humans (2, 51). BabA binds the Lewis b blood group antigen (4). Lewis b is commonly, but not universally, expressed on the surface of gastric epithelial cells (17). HpaA has been characterized as an N-acetylneuraminyllactose-binding hemagglutinin which is critical for mouse colonization (7, 16). The HorB protein is paralogous with BabA, AlpA, and AlpB. An horB mutant strain demonstrates reduced adherence to AGS cells and reduced mouse colonization (52); however, the ligand recognized by HorB has not been identified.

Adherence to host extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules has been shown to contribute to the virulence of a number of bacterial pathogens. For example, the Shr protein of group A streptococcus binds immobilized laminin and fibronectin. Inactivation of the shr gene results in decreased adherence to human epithelial cells and decreased virulence in an animal model (20). The Salmonella protein Rck was first identified as a virulence factor required for serum resistance and host cell invasion (9). It was later found that both Rck and a similar protein, PagC, are able to bind laminin, and their expression in Escherichia coli confers the capacity for adherence to basement membranes and host cells (11). Adherence to ECM is also believed to contribute to virulence of Bacteroides fragilis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis (6, 18, 19, 53). Thus, it would not be surprising for ECM adherence by H. pylori to influence persistence or pathogenesis.

H. pylori has indeed been shown to bind several host ECM molecules, including laminin, type IV collagen, fibronectin, and vitronectin (56, 59, 61), but the relevant H. pylori adhesins have not been identified. Certain isoforms of laminin are produced exclusively by epithelial cells (57). Vitronectin, fibronectin, and laminin are also present in serum, where they can serve as disease markers (5, 45, 63). The presence of serum, which seeps into wound sites following tissue damage, stimulates production of laminin to speed the healing process (1). The basement membrane is separated from the gastric lumen by just a single cell layer. Any damage to this epithelial layer will expose extracellular matrix proteins. Disruptions of tight junctions between these cells by H. pylori will also give the bacteria access to the basement membrane.

Products of the alpAB locus, annotated as omp20-omp21 in the 26695 genome and as hopC-hopB in strain G27, were first implicated in adhesion by Odenbreit et al. in 1996 (38). A subsequent study revealed that alpAB mutants were defective in adherence to human gastric tissue sections (39). The alpAB locus was also found to be ubiquitously present in H. pylori strains and expressed during both mouse and human infections (37, 44). In addition to its influence on adherence, the alpAB locus has been shown to influence host cell signaling and cytokine production (30, 35, 47). Despite the established role of the alpAB locus in adherence, the host receptor has remained elusive.

In the current study, we demonstrate that laminin is a target of both AlpA and AlpB. We further show that an SS1 mutant lacking both AlpA and AlpB surprisingly induces increased inflammation compared with the isogenic wild-type (wt) strain. We anticipate that these findings will facilitate future research on interactions between H. pylori and the gastric mucosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial culture.

H. pylori strains (Table 1) were routinely cultured on Campylobacter blood agar (CBA) containing 10% defibrinated sheep blood (Quad Five, Rygate, MT) and in Ham's F12 medium (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA). Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% O2 and 10% CO2. Strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth with 5% FBS prior to animal inoculation. E. coli was grown in LB broth with 100 μg/ml ampicillin supplementation as appropriate. For induction of pBADalpA or pBADalpB by arabinose, an overnight culture was diluted into fresh medium and grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. The culture was then split into separate tubes, and arabinose was added at the concentration indicated in the figure legends. Incubation was continued for 3.5 h at 37°C or overnight at room temperature, as indicated in the text.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| H. pylori 26695m | Wild-type H. pylori strain, motile variant | 54 |

| H. pylori 26695m alpA::cat (ΔAlpAB) | Contains alpA gene disrupted by chloramphenicol resistance cassette (alpA::cat) cloned in the reverse orientation; also deficient in AlpB; Cmr | This study |

| H. pylori 26695m alpA::cat-fwd | Contains alpA gene disrupted by chloramphenicol resistance cassette (alpA::cat) cloned in the forward orientation; partially deficient in AlpB; Cmr | This study |

| H. pylori 26695m alpB::aphA3 | Contains alpB gene disrupted by kanamycin resistance cassette; Kmr | This study |

| H. pylori 26695m ΔAlpAB/alpA+ | Contains alpA gene disrupted by chloramphenicol resistance cassette (alpA::cat) and alpA inserted into intergenic region; Cmr Kmr; lacks AlpB | This study |

| H. pylori SS1 | Wild-type H. pylori mouse-adapted strain | 28 |

| H. pylori SS1 alpA::cat (ΔAlpAB) | Contains the alpA gene disrupted by chloramphenicol resistance cassette (alpA::cat); also deficient in AlpB; Cmr | This study |

| H. pylori SS1 alpB::aphA3 | Contains alpB gene disrupted by kanamycin resistance cassette; Kmr | This study |

| H. pylori SS1 ΔAlpAB/alpA+ | Contains alpA gene disrupted by chloramphenicol resistance cassette (alpA::cat) and alpA inserted into the HP203-HP204 intergenic region; Cmr Kmr; lacks AlpB | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | λ− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 23 |

| E. coli TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galE15 galK16 rpsL (Strr) endA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II KS (pBS) | Cloning vector; Ampr | Stratagene |

| pBAD/Myc-His | Contains an arabinose-inducible promoter; Ampr | Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA |

| pIR203K04 | Complementation vector containing aphA3 flanked by the H. pylori HP203-HP204 intergenic region; Ampr Kanr | 27 |

| pm5kan2 | An improved version of IR203K04 containing additional restriction sites; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pBSalpA::cat | pBluescript II KS containing most of the alpA gene with an inserted chloramphinicol resistance cassette; Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pBSalpB::aphA3 | pBluescript II KS containing internal fragments of alpB flanking aphA3; Ampr Kmr | This study |

| pBSalpA | pBluescript II KS containing an entire promoter and coding regions of H. pylori 26695m alpA; Ampr | This study |

| pBSalpB | pBluescript II KS containing entire promoter and coding region of H. pylori 26695m alpB; Ampr | This study |

| pBADalpA | pBAD/Myc-His (A) with the H. pylori 26695m alpA coding region; Ampr | This study |

| pBADalpB | pBAD/Myc-His (A) with H. pylori 26695m alpB coding region; Ampr | This study |

Construction of mutant strains.

The alpA::cat strain (ΔAlpAB) was constructed by PCR amplifying DNA from strain 26695m, a motile variant of 26695, using primers omp20F and omp20R (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), cloning the alpA fragment into PstI and XbaI sites of pBluescript KS (yielding pBSalpA) and inserting a nonpolar (lacking transcriptional terminator) chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (27, 42) into the native EcoRI site, located roughly in the middle (position 755 out of 1,548 nucleotides) of the alpA gene. H. pylori strains 26695m and SS1 were transformed with the plasmid containing the interrupted alpA gene using electroporation. Prospective mutants were selected on CBA containing 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The desired mutation was confirmed in isolated colonies by PCR using primers alpAF and alpAR. The cat cassette was originally cloned in the reverse orientation. A new mutant, the alpA::cat-fwd strain, was created by removing and reinserting the cat cassette into the original pBluescript KS plasmid harboring alpA::cat (pBSalpA::cat) and transforming it into 26695m.

Internal regions of the alpB gene (HP0913) were amplified by PCR using 26695m H. pylori chromosomal DNA as a template, Pfx 50 polymerase (Invitrogen), and two primer pairs, alpBF1L/alpBR1L and alpBF2R/alpBR2R. Both fragments were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes (the left fragment with KpnI/XhoI and right with XbaI/SacI) and were sequentially ligated into a pBluescript II SK vector containing a nonpolar kanamycin (Kan) cassette cloned in the EcoRI site of the vector. This resulted in a deletion of 37 nucleotides (nt) of alpB surrounding the naturally occurring EcoRI site. We confirmed that the aphA3 cassette was in the forward orientation. The resulting plasmid (pBSalpB::aphA3) was used as template to amplify alpB::aphA3 (primer pair F1 and R2). This PCR product was used to transform H. pylori strains 26695m and SS1 by electroporation. Transformants were selected on CBA plates supplemented with kanamycin. Single colonies were then restreaked, and chromosomal DNA was isolated and screened by PCR to verify insertion of the aphA3 cassette into the alpB gene using primers alpBF1L and alpBR2R.

The ΔAlpAB strain was complemented with alpA as follows. The vector pm5kan2 (an improved version of previously published intergenic complementation vector pIR203K04 [27]) was digested with KpnI and HincII, releasing the Kanamycin cassette plus the IR204 region. This DNA was ligated into pBSalpA containing entire alpA gene (HP0912) with its native promoter released from pBluescript II KS using the same enzymes. Following ligation, the IR203 region was added back to the resulting plasmid by digestion with SmaI and XbaI, and the IR203 region from m5kan2 released using the same enzymes was inserted. The final plasmid contained the alpA gene (with its promoter) and kanamycin cassette flanked by intergenic regions IR203 and IR204. Transformation of H. pylori was performed as above. Primers used in this study are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

The alpA and alpB genes were placed under arabinose control by cloning the coding sequences of alpA and alpB. The alpA open reading frame was transferred from pBSalpA into pBAD/Myc-His by amplification with primers omp20F7 and the pBluescript T3 primer, followed by digestion with NcoI and KpnI. The pBADalpB plasmid was similarly constructed by amplifying alpB from 26695m DNA using primers alpBF4 and alpBR4 and using XhoI and KpnI restriction sites. We included the native stop codon to prevent addition of C-terminal tags to the protein.

Western blot analysis.

H. pylori extracts were prepared by resuspending pelleted bacteria in Laemmli sample buffer and sonicating. Approximately 20 μg of each protein lysate was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat milk in TBST solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with primary antibodies that had been diluted 1:3,000 in TBST containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 to 2 h at room temperature. Polyclonal antisera specific for AlpA and AlpB were used (39). After four washes in TBST, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; Zymed). Proteins were detected using an ECL-Plus chemiluminescence system (Amersham).

AGS adherence experiments.

AGS cells were seeded into 96-well black plates with transparent bottoms and grown to >90% confluence in F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. H. pylori (SS1 wild-type, ΔAlpAB, and alpB::aphA3 strains) numbers were assessed by ATP assay using a CellTiter-Glo kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) as previously described (49, 62). Equal numbers of bacteria were then fluorescently labeled using a modification of the protocol for the Vybrant Cell Tracer kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), which employs carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE). CFDA-SE stock was diluted to 0.5 mM in 100% ethanol. The bacterial culture was centrifuged and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to addition of 5 μl of CFDA-SE solution. The suspension was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then quenched by addition of 100 μl of fetal bovine serum. Following CFDA-SE labeling, bacterial numbers were confirmed using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). AGS cells were washed once with PBS prior to the addition of 10 μl of density-adjusted bacteria. Positive-control wells without AGS cells were inoculated with the same number of bacteria. AGS cells without added bacteria were used as background. The assay plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 to 1.5 h and then washed twice with PBS. Positive-control wells were not washed. Binding of fluorescently labeled bacteria was assessed using a FluoStar Omega (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany) fluorescent plate reader with excitation at 492 nm and emission at 517 nm. Average background fluorescence was subtracted from values.

Infection of animals.

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC)—Shreveport. H. pylori was grown in brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 5% FBS under conditions described above. Viability of cultures was verified microscopically and by ATP assay (54) prior to use. The cultures were pelleted and resuspended in 0.9% NaCl to give concentrations of 1 × 109 to 1.5 × 109 CFU/ml. Male C57BL/6 Mice (Harlan Laboratories) or female Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus; Charles River Laboratories) were orogastrically inoculated with 200-μl aliquots (>2 × 108 CFU) of concentrated H. pylori suspensions. Animals were age matched within an experiment and were 1 to 6 months old at the time of inoculation. In each experiment, the infection procedure was repeated 1 or 2 days later to ensure infection. The bacterial density of each inoculum was determined by plating serial dilutions on CBA. At the time points indicated below, animals were euthanized, and the stomachs were removed and opened along the greater curvature. One half of each antrum was processed as previously reported (27). Colonization levels were determined by enumerating colonies from serial dilutions of gastric homogenates plated on CBA supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (27). The remaining half of the antrum was formalin fixed, and slides were prepared from cross-sections. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides were examined blindly by a pathologist for the presence of lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammation according to the method of Eaton et al. (15). Inflammation was scored on a six-point scale as follows: 0, no inflammation; 1, mild, multifocal inflammation; 2, mild, widespread inflammation; 3, mild, widespread and moderate, multifocal inflammation; 4, moderate, widespread inflammation; 5, moderate, widespread and multifocal, severe inflammation; and 6, severe, widespread inflammation. Neutrophils were scored on a three-point scale according to standard pathology practice, as follows: 0, no neutrophils; 1, mild (focal cryptitis); 2, moderate (cryptitis with focal abscess); 3, severe (cryptitis with multifocal abscesses).

Surface adherence assays.

Matrigel was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Mouse collagen IV-coated multiwell plates were obtained from BD Biosciences, and mouse laminin-1 was obtained from Trevigen (catalog number 3400-010-01; Gaithersburg, MD). Multiwell plates were coated with proteins (1 μg/cm2) in F12 medium overnight. Plates were subsequently washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. Adherent bacteria were detected either by quantifying bacterial ATP (see above) or by visualizing fluorescently labeled bacteria. Bacteria were fluorescently labeled with CFDA-SE (see above).

Adherence under controlled shear experiments.

The ability of bacteria to resist removal from a laminin-coated surface was determined by applying shear stress to formalin-fixed H. pylori and E. coli adhered to laminin. Briefly, a BioFlux instrument and an associated 48-well, 0- to 20-dyn/cm2 microfluidic plate (Fluxion Biosciences, Inc. San Francisco, CA) were used to apply shear forces to the bacteria. Microfluidic channels were coated with laminin (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) at 20 μg/ml in serum-free, CO2-independent medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 4 h at 37°C. The microfluidic channels were washed with PBS (calcium and magnesium free) for 10 min. The formalin-fixed bacteria were prepared by suspending them in 0.85% saline containing propidium iodide at a final concentration of 30 μM for 25 min. The bacterial cells were washed by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min to remove the propidium iodide. The cells were resuspended in fresh 0.85% saline. The prepared bacteria were perfused into the microfluidic channels for 10 min at 0.5 dyn/cm2 to permit maximal association of bacteria with laminin. Nine wells were used for each bacterial strain. The perfusion solution was changed to PBS, and the flow rate was increased to 1 dyn/cm2. Microscopy data were collected after 10 min at 1 dyn/cm2 (low shear force) and again after 10 min at 20 dyn/cm2 (high shear force) using a BioFlux 1000 Imaging Workstation (Fluxion). Fluorescence intensity data were processed using BioFlux Montage software (Fluxion).

Flow cytometry.

Labeling of proteins with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was accomplished using an FITC labeling kit (Calbiochem catalog number 343210; EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA). Aliquots (1-ml) of logarithmic-phase H. pylori grown in Ham's F12 medium containing 1% FBS were pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 × g and resuspended in filtered PBS containing 500 μg/ml bovine serum albumin. FITC-labeled protein (2 μl of a 0.1 mg/ml solution) was added to tubes, and samples were incubated at 37°C in the dark for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged and resuspended in a solution of 2% (vol/vol) ultrapure, methanol-free formalin (catalog number 04018; Polysciences, Warrington, PA) diluted in PBS. Flow cytometric determination of protein binding was performed on a BD LSRII instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) made available through the Research Core Facility at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center—Shreveport (Shreveport, LA). The LSRII has a coherent sapphire laser for 488-nm excitation, a JDS uniphase HeNe laser for 633-nm excitation, and a coherent VioFlame for 405-nm excitation. Data analysis was performed using FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorter) Diva software (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR.). A minimum of 20,000 events was collected for each sample. Gating of P2 was set to exclude at least 97.5% of the unstained population, and the same gate setting was used for all comparisons within a single experiment. Unlabeled bacteria and binding to FITC-BSA or FITC-goat anti-rabbit IgG were used as negative controls to separate natural autofluorescence and nonspecific binding from fluorescence resulting from FITC-laminin binding. Histograms were prepared by plotting the percentage of maximal fluorescence versus fluorescence.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

Experiments were performed on a Biacore 2000 instrument (GE Healthcare). Mouse laminin-1 (Trevigen) was diluted to 100 μg/ml in sodium acetate (10 mM, pH 4.8) and coupled to a CM5 biosensor chip (GE Healthcare) using an amine coupling kit (BR-1000-50; GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer's instructions. Bacteria were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at concentrations between 107 and 1010 cells/ml. The level of immobilized mouse laminin-1 in flow cells was equal to 1,989 resonance units. Control flow cells were activated with amino-coupling reagents and blocked with ethanolamine. Signals due to nonspecific binding of bacteria to the surface of control cells were subtracted. The instrument was used in the Kinject mode. Bacterial suspension (150 μl) was injected over the sensor chip surface at a rate of 50 μl/min, followed by a 300-s dissociation period. The chip surfaces were regenerated by a 50-μl pulse of 6 M guanidine-HCl in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5. The order in which samples were run was changed in each experiment to control for possible effects due to run order, and findings were consistent regardless of sample order. To calculate the observed rates of dissociation of different bacterial strains from laminin-1, the decreasing signal in the dissociation portion of sensograms was fitted to a single-exponential function. KaleidaGraph (version 3.06; Synergy Software, Reading, PA) was used for nonlinear least-squares fitting of dissociation data.

Statistics.

For analysis of inflammation, colonization, and laminin binding in the controlled-flow system, we used a two-tailed, homoscedastic Student's t test. A D'Agostino-Pearson normality test suggested normal distribution.

RESULTS

H. pylori alpA::cat lacks both AlpA and AlpB.

We inserted a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) cassette lacking a transcriptional terminator (27, 42) into the coding sequence of alpA. Polar effects on alpB expression were not expected, based on our own experience and that of other laboratories using the nonpolar cat cassette (27, 42).

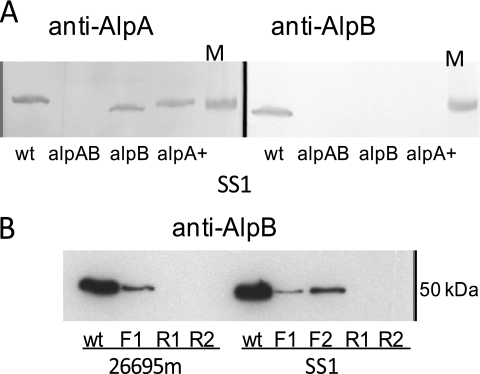

Western blot analysis carried out using the anti-AlpA and anti-AlpB antibodies (39) show that both proteins are absent in the alpA::cat mutant in both the 26695m and SS1 strain backgrounds (Fig. 1A). A mutant lacking only AlpA has not been reported by other investigators either, but no explanation has been given (31, 39). We will henceforth refer to the alpA::cat mutant as the ΔAlpAB strain to make it clear that both proteins are missing.

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of H. pylori strains. Blots of SDS-PAGE gels containing 40 μg/lane protein from each strain were probed with polyclonal antibodies specific for AlpA or AlpB. (A) Loss of AlpA and AlpB in mutant strains. Extracts from strain SS1 wild-type (wt), ΔAlpAB (alpAB), alpB::aphA3 (alpB), and ΔAlpAB/alpA+(alpA+) strains were probed with antibodies against AlpA (left) and AlpB (right). The 50-kDa band from a molecular mass marker (M) is shown on the right of each blot. (B) Reversing the orientation of the chloramphenicol resistance cassette influences AlpB production. Extracts from both 26695m and SS1 were probed with anti-AlpB. Labels represent the wt, clones with the cassette in forward orientation (F1 and F2), and clones with the cassette in reverse orientation (R1 and R2). Each Western blot analysis was repeated at least once.

In the first ΔAlpAB clones, the cat cassette was cloned in the reverse orientation, meaning that alpB transcription would be solely due to the alpA promoter. We recloned the cat cassette in the forward orientation so that both the alpA and cat promoters would drive transcription of alpB. Western blot analysis of independent clones revealed greatly reduced AlpB levels in these strains compared to the wild type (Fig. 1B). This was true for both SS1 and 26695m. The alpA::cat-reverse (ΔAlpAB) strain was used in experiments to reduce ambiguity of results.

We created an alpB mutant by inserting an aphA3 kanamycin resistance cassette into the alpB coding region. Western blot analysis confirmed that only AlpB was missing from this strain (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, AlpA migrates faster in the SS1 alpB::aphA3 strain than in the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 1A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This effect was observed with blots prepared from independent cultures but is not seen in strain 26695m.

The ΔAlpAB mutant was complemented with alpA inserted into an intergenic region (yielding the ΔAlpAB/alpA+ strain). Western blots on both 26695m and SS1 revealed that alpA was now expressed, but alpB expression was not restored (Fig. 1A). Therefore, this mutant is expected to behave similarly to the alpB::aphA3 mutant.

H. pylori ΔAlpAB and alpB::aphA3 strains show decreased adherence to AGS cells.

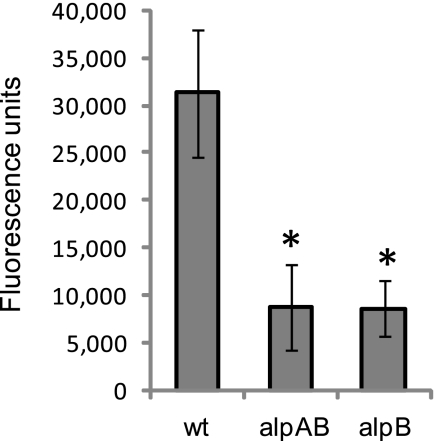

The alpAB locus has been reported to influence adherence to the Kato III and AGS gastric cell lines (36, 38), leading us to expect similar results with our alpA::cat mutant. Photomicrographs of fluorescently labeled 26695m wild-type and ΔAlpAB cells adhering to AGS cells did indeed show that the ΔAlpAB cells adhere less well to AGS cells than the wild type. The average number of 26695m ΔAlpAB bacteria per cell was reduced by about half (data not shown). For further confirmation, we measured total fluorescence with a fluorescence plate reader. SS1 wild-type, ΔAlpAB, and alpB::aphA3 strains revealed similar adherence decreases, as seen previously by microscopy. Statistically significant adherence differences were found in three of four experiments for the wild type versus the ΔAlpAB strain and four of four experiments for the wild type versus the alpB::aphA3 strain (Fig. 2). We expected that the ΔAlpAB mutant would adhere less to AGS cells than the alpB::aphA3 mutant; however, there was no apparent difference between these strains. These data confirm that interruption of the alpAB locus in the 26695m strain background alters one or more adhesion molecules relevant to H. pylori attachment to a human gastric cell line, but they do not clarify whether both proteins are involved or only AlpB.

Fig. 2.

Adherence of ΔAlpAB and alpB::aphA3 to AGS cells. Confluent monolayers of AGS cells were inoculated with equal numbers of fluorescently labeled SS1 wild-type (wt), ΔAlpAB (alpAB), and alpB::aphA3 (alpB) strains. Wells were washed after 1.5 h, and total fluorescence was measured. Background fluorescence from uninfected AGS cells was subtracted from the measurements. Data represent averages and standard deviations from 18 wells per strain and are representative of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.0005 for wild-type versus the ΔAlpAB strain and the wild type versus the alpB::aphA3 strain.

Colonization of mice and gerbils with SS1 ΔAlpAB.

Previous studies clearly indicate a role for the alpAB locus in mediating adherence in vitro; however, in vivo studies examining the role of the alpAB locus in colonization and pathogenesis have been limited. Reduced numbers of colonized animals have been noted in guinea pigs inoculated with H. pylori strain GP15 alpA and alpB mutants (13). Abrogation of alpAB in strain TN renders the bacteria unable to colonize mice while the same mutation in a 43505 strain background reduces colonization density (31).

In four independent experiments, mice were colonized for 6 to 9 weeks (total of 16 wt- and 16 ΔAlpAB-infected mice) or 5 months (7 wt- and 10 ΔAlpAB-infected mice). In each individual experiment, SS1 ΔAlpAB colonized mice at a lower density, ranging from 2- to 800-fold lower than infection with the isogenic wild-type strain (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material; also data not shown). Colonization levels and the differences between SS1 wt and SS1 ΔAlpAB colonization did not appear to differ between 2 and 5 months, meaning that the SS1 ΔAlpAB colonization defect is stable over this time period. Considerable variation in bacterial counts led to lack of statistical significance in any individual experiment, and when all data are pooled, no difference is seen between SS1 wt and SS1 ΔAlpAB colonization levels. We were able to evaluate colonization levels of 10 gerbils infected with SS1 wt, 11 gerbils infected with SS1 ΔAlpAB, and four animals infected with the alpB::aphA3 strain and found no appreciable differences between them. The means and standard deviations were as follows: for the wild type, 3.7 × 106 ± 1.5 × 106 CFU/g; for the AlpAB strain, 3.3 × 106 ± 1.6 × 106 CFU/g; for the alpB::aphA3 strain, 4.34 × 106 ± 3.86 × 106 CFU/g.

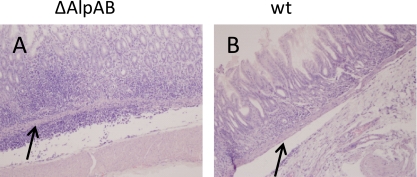

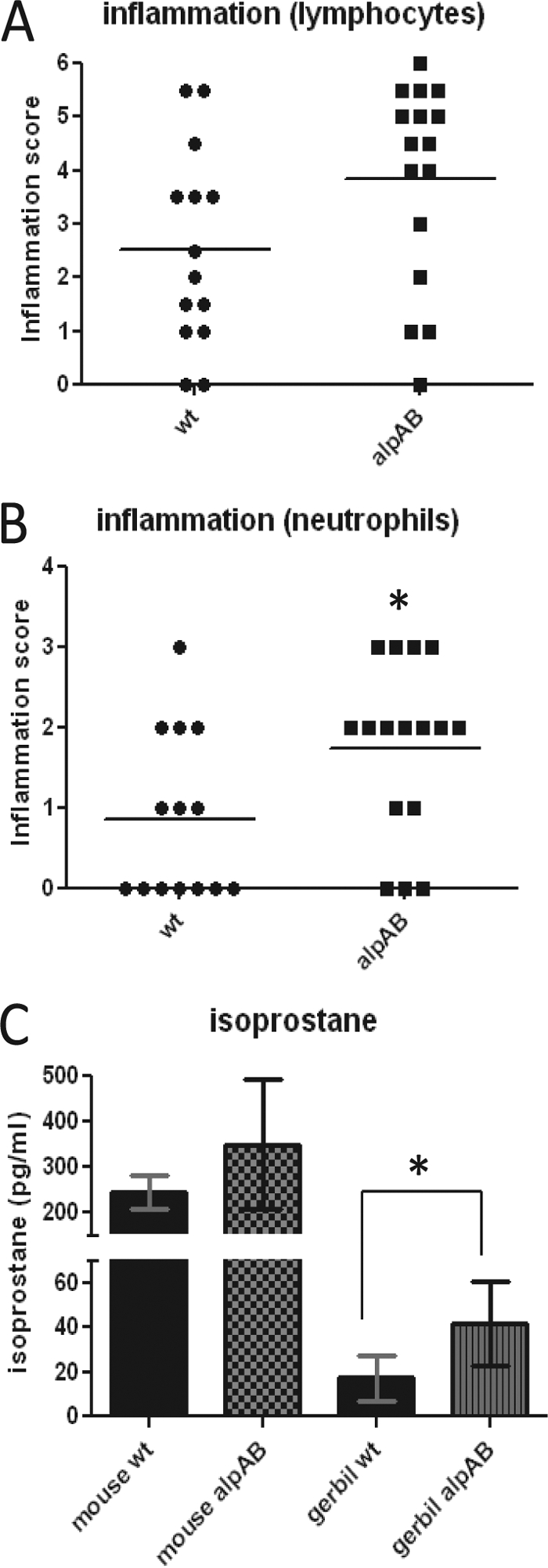

Mice are commonly used in studies of H. pylori colonization, but mice do not normally develop ulcers or cancer following colonization by H. pylori. Gerbils develop a more robust H. pylori-triggered inflammatory response than do mice and more readily develop ulcers and gastric cancer following H. pylori infection (32). We expected that the ΔAlpAB mutant would adhere less well to the gastric mucosa, thus decreasing inflammation in gerbils. To test this hypothesis, we colonized gerbils with SS1 wt or SS1 ΔAlpAB for 8 to 12 weeks. Coded hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the antral mucosa were scored for lymphocytic infiltration on two separate occasions by pathologists using criteria outlined by Eaton et al. (15). Surprisingly, many of the gerbils infected with SS1 ΔAlpAB displayed severe, transmural inflammation extending almost to the surface of the mucosa, whereas inflammation caused by wild-type SS1 is typically limited to the lower third of the mucosa, closest to the muscularis mucosae (Fig. 3 and data not shown). The inflammation was largely chronic in nature, but more neutrophils were noted in ΔAlpAB-infected animals, leading us to have the slides scored separately for neutrophils. As seen in Fig. 4A and B, infiltration of lymphocytes and neutrophils was strongly increased in ΔAlpAB-infected gerbils compared with wild-type-infected animals. The differences in lymphocyte infiltration did not quite reach significance (P = 0.065), but the increase in neutrophil infiltration reached the significance threshold (P = 0.027).

Fig. 3.

H&E-stained antral sections from gerbils infected for 8 weeks. (A) Antral section from an SS1 ΔAlpAB-infected animal. Severe inflammation (dark purple areas) is seen extending below the muscularis mucosae (arrows). (B) Antral section from an SS1 wild-type-infected animal.

Fig. 4.

Inflammation in animals infected with the SS1 wild-type or ΔAlpAB strain. (A) Lymphocytic infiltration seen in the antral regions of gerbils infected with the wt or ΔAlpAB (alpAB) strain. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of formalin-fixed tissue were evaluated by a pathologist. Graphed data are compiled from three independent experiments (P = 0.065). (B) Neutrophilic infiltration of antral regions from the same animals as used for the experiment shown in panel A (P = 0.027). (C) Plasma 8-isoprostane levels from mice and gerbils infected with the wild-type or ΔAlpAB strain (P = 0.023). Isoprostane data represent one mouse experiment (3 wt-infected and 5 ΔAlpAB-infected mice at 5 months of infection) and one gerbil experiment (6 wt-infected and 5 ΔAlpAB-infected gerbils at 12 weeks of infection).

Plasma isoprostane is a biomarker of lipid peroxidation that has been used to monitor systemic inflammation due to reperfusion and septic shock and atherosclerosis (3, 46). Plasma was collected from gerbils in one experiment. Analysis of isoprostane concentrations showed a significant increase in ΔAlpAB-infected gerbils compared to wild-type-infected gerbils (P = 0.023) (Fig. 4C). Analysis of plasma from mice infected with SS1 wild-type and the ΔAlpAB strain shows a similar trend (Fig. 4C).

The ΔAlpAB mutant is defective in binding to basement membrane components.

We have previously found that serum, which contains ECM proteins, causes aggregation in H. pylori (62). Aggregation is greatly reduced in the ΔAlpAB strain, leading us to suspect that ECM proteins might be involved. Incubation of fluorescently labeled 26695m wild-type and ΔAlpAB strains in wells coated with Matrigel, a mixture of basement membrane proteins secreted by Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcoma cells, revealed fewer ΔAlpAB than wild-type bacteria adhering to the Matrigel (data not shown). These results encouraged us to investigate which Matrigel component was responsible for the differential adherence of 26695m wild-type and ΔAlpAB H. pylori cells.

AlpA and AlpB bind laminin.

The primary components of Matrigel are collagen IV and laminin. Experiments performed in collagen IV-coated plates did not reveal any differences between the wild type and the alpA mutant (data not shown), suggesting that collagen IV is not the receptor for AlpA/AlpB. We next examined binding to mouse laminin-1. Preliminary experiments performed in standard 24-well plates coated with laminin suggested that the ΔAlpAB mutant was defective in laminin binding (data not shown).

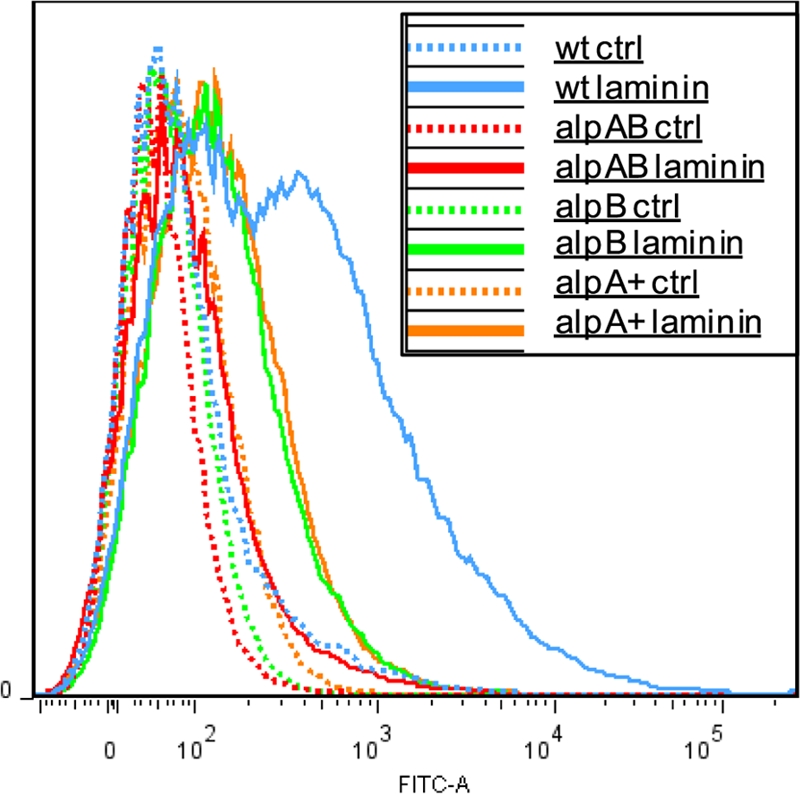

Laminin binding was further investigated by labeling mouse laminin-1 with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), incubating the protein with H. pylori, and measuring bacterial fluorescence levels by flow cytometry. Greater fluorescence (horizontal axis) indicates that more FITC-laminin was bound to the bacteria. The vertical axis represents the proportion of bacteria displaying a particular level of fluorescence. As seen in Fig. 5, the 26695m ΔAlpAB strain (red line) shows a very small fluorescence shift following incubation with FITC-laminin. The alpB::aphA3 strain (green line) shows fluorescence intermediate between the wild-type and ΔAlpAB strain levels. The alpA-complemented strain shows binding identical to that of the alpB::aphA3 strain (yellow line). Variations of this experiment were repeated on independent cultures of both 26695m and SS1 with similar results. We used goat anti-rabbit FITC-IgG (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) and FITC-BSA to control for nonspecific binding. In addition, we found that mutants devoid of other H. pylori putative outer membrane proteins (HP0876 and omp3) bound laminin similarly to the wild type (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Binding of wild-type, ΔAlpAB, and alpB::alphA3 mutant H. pylori 26695m strains to laminin. H. pylori was incubated with FITC-labeled laminin for 1 h. Bacteria were washed and fixed with formalin prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Increased fluorescence due to binding of FITC-laminin is shown on the x axis, with unlabeled bacteria serving as controls. Data are shown for the wt, ΔAlpAB (alpAB), alpB::aphA3 (alpB), and ΔAlpAB/alpA+ (alpA+) strains. Each curve represents analysis of 50,000 bacteria. The data shown are representative of numerous (≫3) flow cytometry experiments.

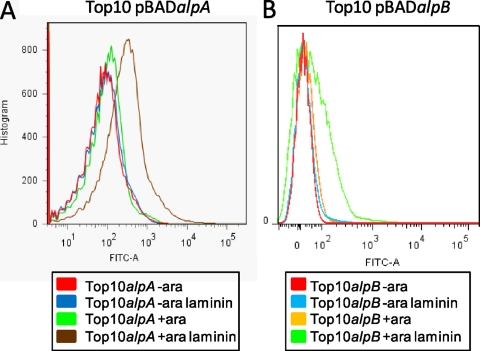

Binding studies using intact H. pylori suggested that AlpA and/or AlpB bind laminin but did not rule out effects on synthesis of other surface adhesins. Since AlpA is predicted to be an integral membrane protein with a porin-like structure and 14 transmembrane domains, we do not expect that it can be purified in its native conformation. Instead, we expressed alpA and alpB in E. coli.

We initially cloned the intact alpA gene with its native promoter into pBluescript KS (pBS). E. coli DH5α containing pBSalpA gained the ability to adhere to Matrigel (data not shown). Further adherence experiments were performed using the BioFlux controlled-flow system, which allows adherence interactions to be measured in multiple chambers under precise flow and shear stress conditions. Experiments performed using laminin-coated microfluidic channels similarly revealed that numbers of H. pylori ΔAlpAB mutants were lower than those of the wild-type while pBSalpA confers increased laminin adherence to E. coli. Exposure of bacteria to 1 dyn/cm2 (very low shear stress) significantly lowered adherence of the ΔAlpAB strain compared with the wild-type strain (P < 0.0005), but adherence of the alpB::aphA3 strain was not reduced (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Increasing the flow rate to 20 dyn/cm2 further reduced numbers of all three H. pylori strains, yet binding levels remained significantly different between the wild-type and ΔAlpAB strains (data not shown). These results are consistent with those obtained in an earlier experiment using the H. pylori 26695m wild type strain and the ΔAlpAB mutant (not shown). We similarly tested E. coli containing pBS or pBSalpA. Presence of alpA in the vector dramatically increased adherence of E. coli to laminin (see Fig. S4).

In spite of increased laminin adherence by E. coli DH5α containing the pBSalpA plasmid, we were unable to detect the presence of an additional protein at 56 kDa by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. The AlpA antiserum cross-reacts heavily with E. coli proteins, making it difficult to detect an extra band by Western blot analysis. In order to improve transcriptional control, we cloned both alpA and alpB separately without their native promoters into pBAD/Myc-His. We included the native stop codons to prevent addition of C-terminal tags to the proteins. E. coli TOP10(pBADalpA) cultures were induced with l-arabinose at concentrations of 0.02%, 0.2%, and 2% at 37° for 4 h or room temperature overnight. Bacterial extracts from these cultures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE for the presence of an additional band at around 50 kDa. The expected band was more evident in extracts from cultures induced at room temperature (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material; also data not shown), possibly due to decreased misfolding (21). Bacterial cell elongation and lysis were noted in E. coli TOP10(pBADalpA) induced with the higher arabinose concentrations, indicating toxicity. Bacterial abnormalities were even more prominent in TOP10(pBADalpB) (data not shown). AlpA was primarily seen in the insoluble fraction of E. coli after lysis by sonication (see Fig. S5B). This suggests that AlpA is targeted to the membrane although its presence in inclusion bodies cannot be ruled out. We also detected increased binding of FITC-laminin to E. coli(pBADalpA) and E. coli(pBADalpB) following induction, confirming surface localization of AlpA and AlpB (Fig. 6). The laminin-binding capacities of E. coli expressing alpA and alpB cannot be directly compared because protein expression levels vary considerably from one experiment to the next, and we cannot ensure that expression levels are similar between strains.

Fig. 6.

Laminin binding of E. coli TOP10 expressing alpA or alpB. E. coli bacteria harboring pBADalpA or pBADalpB were induced with 0.02% arabinose (ara) overnight at room temperature. Bacteria were incubated with FITC-laminin for 1 h. Bacteria were washed and fixed with formalin prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Increased fluorescence due to binding of FITC-laminin is shown on the x axis. Data are shown for uninduced (−ara) and unstained, induced (+ara) and unstained, uninduced FITC-laminin-stained (−ara laminin), and induced FITC-laminin-stained (+ara laminin) TOP10 cells expressing alpA and alpB. Each curve represents analysis of 50,000 bacteria. The data shown are representative of three flow cytometry experiments.

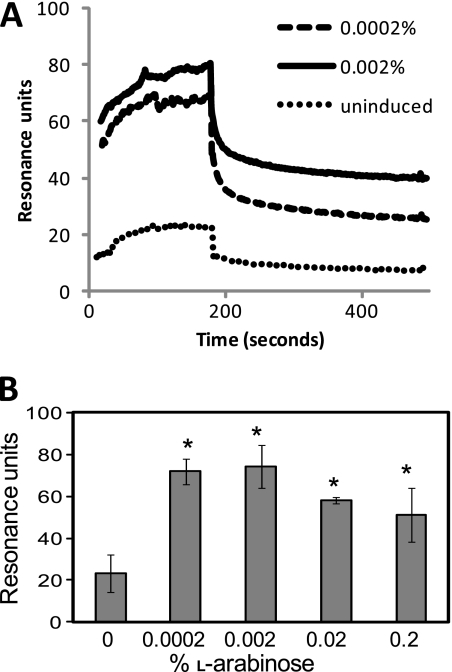

We used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) as a more sensitive measure of interactions between AlpA and mouse laminin-1 coupled to a sensor chip. Baseline laminin binding was measured using uninduced E. coli TOP10(pBADalpA). Three experiments were carried out using independent cultures induced with 0.0002% to 0.2% l-arabinose. In all experiments, increased laminin adherence could be seen in cultures induced with 0.0002% l-arabinose, and similar or slightly greater adherence was seen using cultures induced with 0.002% l-arabinose (Fig. 7A). Adherence decreased somewhat in cultures induced by 0.02% and 0.2% l-arabinose but remained above the baseline seen for uninduced cultures (Fig. 7B). We suspect that overexpression of alpA in E. coli results in misfolding and/or accumulation of AlpA in the periplasm, as has been suggested to occur with other outer membrane proteins (12, 33). This could explain decreased laminin binding seen with E. coli(pBADalpA) induced with more than 0.002% arabinose. Extensive lysis and clumping of arabinose-induced E. coli(pBADalpB) make it unsuitable for SPR experiments.

Fig. 7.

Surface plasmon resonance of E. coli(pBADalpA) interaction with surface-bound laminin. (A) SPR analysis of E. coli TOP10(pBADalpA) interaction with surface-bound laminin. Dotted line, uninduced; dashed line, induced with 0.0002% arabinose; solid line, induced with 0.002% arabinose. (B) Average binding of E. coli(pBADalpA) induced with different concentrations of arabinose. Binding experiments were repeated three times for each induction condition. Error bars represent standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 versus uninduced control.

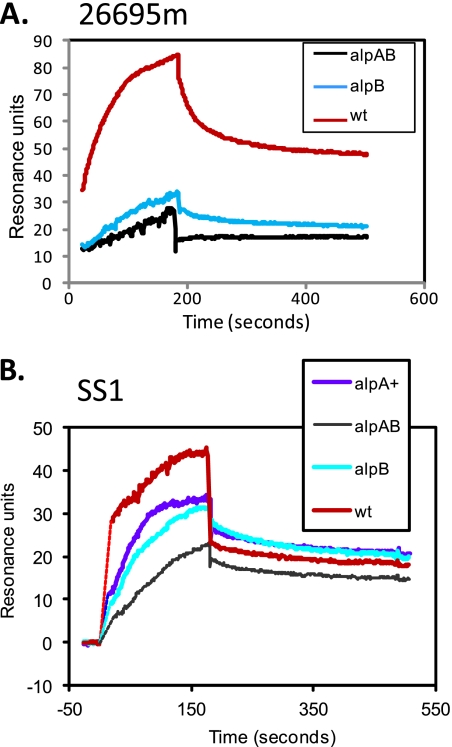

SPR experiments with H. pylori wild-type 26695m and SS1 strains and the isogenic ΔAlpAB and alpB::aphA3 mutants provided further confirmation of the roles of AlpA and AlpB in binding laminin. In both strains, the ΔAlpAB strain showed the least laminin binding (Fig. 8). Lack of AlpB alone substantially reduced laminin binding. Complementation of the ΔAlpAB strain with alpA in the SS1 strain background demonstrates that the ΔAlpAB/alpA+ strain behaves similarly to the alpB::aphA3 strain, as expected (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis of H. pylori interaction with surface-bound laminin. Wild-type (wt), ΔAlpAB (alpAB), and alpB::aphA3 (alpB) strains are shown in panels A (strain 26695m background) and B (strain SS1 background). Panel B includes the above strains and the ΔAlpAB/alpA+ (alpA+) strain.

For strain SS1, the amplitudes of the dissociation portion of the SPR traces were large enough to permit calculation of dissociation rates. We found that dissociation rates for SS1 wild-type, ΔAlpAB, and alpB::aphA3 strains were essentially the same (0.006 s−1 to 0.007 s−1). The association rate, which is concentration dependent, cannot be calculated from our data which was obtained using a single laminin concentration. However, the observed asymptotes of the association portions of the SPR traces indicate that the affinity is highest for wild-type strains and lowest for ΔAlpAB strains.

DISCUSSION

The alpAB operon was previously identified as a locus encoding outer membrane proteins which play a role in adherence to host cells and tissues (35, 38, 39). In this report, we show that both AlpA and AlpB bind laminin. We also show that lack of AlpA and AlpB paradoxically increases the inflammatory response in gerbils.

We were surprised to find that both AlpA and AlpB were absent in the mutant obtained by inserting a nonpolar cassette into alpA. When we reversed the orientation of the antibiotic resistance cassette so that both the alpA promoter and the cat promoter would drive alpB expression, we found that AlpB synthesis was still dramatically reduced (Fig. 1B). Abrogation of the alpB gene did not reduce AlpA levels, but it did cause a strain-dependent downshift in the apparent molecular weight of AlpA. Complementation of the ΔAlpAB mutant with alpA restored AlpA to normal levels but did not restore AlpB production (Fig. 1A). These data lead us to suspect that AlpA and AlpB interact and/or that cotranscription is required. The complete conservation of both alpA and alpB in H. pylori strains (44) suggests that the functions of these proteins are not completely redundant, in spite of their apparently similar roles in binding laminin. A number of experiments are planned to address transcriptional regulation of alpA and alpB and the potential for AlpA-AlpB interaction on the cell surface. Complementation of alpB alone and of the entire alpAB locus will allow us to study transcriptional and translational regulation.

One would expect that abrogation of alpAB expression would decrease both colonization and inflammation. On the contrary, we found severe inflammation in ΔAlpAB strain-infected gerbils (Fig. 3 and 4). The SS1 strain used in our animal studies is unable to translocate CagA (10, 26). Therefore, we believe that inflammation seen in SS1 alpA::cat-infected gerbils must be induced via CagA-independent mechanisms.

The effect of the ΔAlpAB mutant on gastric inflammation in gerbils is counterintuitive, but we have several hypotheses to explain this result. Although ΔAlpAB strain colonization levels were equal to those of the wild type in gerbils, it is possible that the distribution of bacteria within the mucosa is altered. Fewer H. pylori bacteria attaching to cells or penetrating the mucosa would reduce the opportunities of H. pylori to interact with (and thus influence) epithelial and immune cells. This hypothesis is supported by studies showing that the alpAB locus alters intracellular signaling and cytokine production in epithelial cell lines (31, 36, 47). Of particular interest, interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression by MKN28 gastric epithelial cells shows alpAB dependence (31). Although traditionally regarded as a proinflammatory cytokine, IL-6 is increasingly appreciated for its significant anti-inflammatory properties (40). Thus, loss of AlpA/AlpB-mediated IL-6 expression in vivo could contribute to the severe inflammatory response. We are currently investigating how AlpA and AlpB influence cytokine induction and the precise localization of H. pylori within gastric tissue in mice and gerbils. We will also examine histology of the mouse stomach after several months of infection.

Loss of AlpA and AlpB results in profoundly reduced laminin binding in strains 26695m and SS1 (Fig. 5 and 8); however, the relative contributions of AlpA and AlpB are not entirely clear. Abrogation of both AlpA and AlpB yields the most severe laminin-binding defect, but deletion of alpB alone substantially reduces laminin binding. The ΔAlpAB and alpB::aphA3 strains behave almost identically in the AGS adherence experiments but differently in other experiments. This could indicate that the context in which laminin is encountered alters binding properties.

Surface plasmon resonance experiments yielded insights into the laminin binding kinetics of wild-type H. pylori. The predicted association rate of the SS1 wild-type is higher than that of the alpB::aphA3 strain, with further reductions seen in the ΔAlpAB mutant. This indicates that AlpA and AlpB contribute to increased affinity of H. pylori to laminin. In contrast, the dissociation rates are similar regardless of alpAB status. These patterns would result in a net increase in the number of AlpAB-positive H. pylori cells adhering to laminin-containing tissue. At the same time, the similar dissociation rates suggest that presence of AlpAB would not prevent H. pylori from detaching from a laminin-containing substrate and relocating to a new region. Continual turnover of epithelial cells could put firmly attached bacteria at a disadvantage as cells on the epithelial surface are sloughed. Shear forces in the vasculature range from ∼2 dyn/cm2 to over 3,000 dyn/cm2 (22). The forces encountered by H. pylori in the stomach are not known, but continuous extrusion of mucin by crypt cells should exert force on bacteria invading gastric crypts.

Our studies complement previous work demonstrating that H. pylori membrane protein extracts or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are capable of binding laminin (43, 59, 60). Valkonen and colleagues found that N-acetylneuraminyllactose, sialylated fetuin, and certain other molecules significantly inhibited binding, suggesting an interaction between an H. pylori surface protein and glycosylated portions of laminin (59). Odenbreit and colleagues showed that mutation of the sabA gene in strain J99 abrogated laminin binding in a dot blot overlay assay, suggesting that SabA could also bind laminin (37). The sabA gene is reportedly not expressed in strain 26695 (37), and expression of sabA in strain SS1 has not been determined.

We have not yet determined whether AlpA and AlpB have additional host targets, nor have we explored host species specificity of laminin binding. Some bacterial adhesins have been found to bind to more than one ECM molecule (19, 20). Although collagen IV does not appear to be a ligand for AlpA/AlpB, we have not yet examined binding to fibronectin or other proteins. Our studies employed mouse laminin-1. Since mutation of the alpAB locus alters adherence to a human cell line and pathogenesis in the gerbil model, we anticipate that AlpA and AlpB will bind laminins from a range of species. This would not be surprising for a protein as highly conserved as laminin. Mouse and human laminin share 76% identity (86% similarity) in the alpha subunit and 92% identity in the beta and gamma subunits.

How does adherence to a basement membrane protein influence adhesion in vivo when the basement membrane is not normally exposed? Several studies support the hypothesis that ECM binding by bacteria does influence virulence. Laminin binding has been shown to increase virulence of group A Streptococcus and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (9, 20). Both of these pathogens normally encounter an intact epithelium. Moreover, there are two known mechanisms through which laminin binding can influence adherence of bacteria to host cells. The most obvious is by direct interaction between bacterial surface components and laminin. Alternatively, soluble laminin present in serum/plasma can bind to laminin receptors present on the apical surface of cells, and bacterial adhesins can subsequently bind to this laminin. This alternate laminin-mediated adherence mechanism has been demonstrated for E. coli expressing the Salmonella laminin-binding protein genes, rck and pagC (11). Finally, production of laminin γ-1 is induced in AGS cells by exposure to H. pylori (8), suggesting that H. pylori induces production of the ligand to which it binds. This same laminin isoform has been shown to be increased in gastric adenocarcinoma compared with normal surrounding tissue (8).

Identification of laminin as the host target of both AlpA and AlpB will permit more targeted investigations of the functional domains of AlpA and AlpB, of the recognized laminin domain(s), and of how interactions between these proteins influence host cell signaling and the inflammatory response.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI063307-01 (T.L.T.), 1R21AI085231-01A1 (T.L.T.), and RO1GM20818 (R.E.R.) from the NIH and an intramural award from LSU Health Sciences Center.

We thank Shannon Mumphrey in the LSUHSC—Shreveport Research Core Facility for flow cytometry analysis. We thank Rainer Haas for antisera and useful discussions and Hynda Kleinman for advice on handling of laminin solutions. The pm2Kan5 vector was developed by Ellen Hildebrandt. Shantell Ceaser assisted with preliminary experiments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amano S., Nishiyama T., Burgeson R. E. 1999. A specific and sensitive ELISA for laminin 5. J. Immunol. Methods 224:161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aspholm M., et al. 2006. SabA is the H. pylori hemagglutinin and is polymorphic in binding to sialylated glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2:e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Basu S., Helmersson J. 2005. Factors regulating isoprostane formation in vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7:221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boren T., Falk P., Roth K. A., Larson G., Normark S. 1993. Attachment of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric epithelium mediated by blood group antigens. Science 262:1892–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd N. A., Bradwell A. R., Thompson R. A. 1993. Quantitation of vitronectin in serum: evaluation of its usefulness in routine clinical practice. J. Clin. Pathol. 46:1042–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brissette C. A., Verma A., Bowman A., Cooley A. E., Stevenson B. 2009. The Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein ErpX binds mammalian laminin. Microbiology 155:863–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carlsohn E., Nystrom J., Bolin I., Nilsson C. L., Svennerholm A. M. 2006. HpaA is essential for Helicobacter pylori colonization in mice. Infect. Immun. 74:920–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang Y. T., et al. 2006. Distinct gene expression profiles in gastric epithelial cells induced by different clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori-implication of bacteria and host interaction in gastric carcinogenesis. Hepatogastroenterology 53:484–490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cirillo D. M., et al. 1996. Identification of a domain in Rck, a product of the Salmonella typhimurium virulence plasmid, required for both serum resistance and cell invasion. Infect. Immun. 64:2019–2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crabtree J. E., Ferrero R. L., Kusters J. G. 2002. The mouse colonizing Helicobacter pylori strain SS1 may lack a functional cag pathogenicity island. Helicobacter 7:139–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crago A. M., Koronakis V. 1999. Binding of extracellular matrix laminin to Escherichia coli expressing the Salmonella outer membrane proteins Rck and PagC. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danese P. N., Silhavy T. J. 1998. Targeting and assembly of periplasmic and outer-membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32:59–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Jonge R., et al. 2004. Role of the Helicobacter pylori outer-membrane proteins AlpA and AlpB in colonization of the guinea pig stomach. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dubois A., Boren T. 2007. Helicobacter pylori is invasive and it may be a facultative intracellular organism. Cell Microbiol. 9:1108–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eaton K. A., Cover T. L., Tummuru M. K., Blaser M. J., Krakowka S. 1997. Role of vacuolating cytotoxin in gastritis due to Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect. Immun. 65:3462–3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans D. G., Karjalainen T. K., Evans D. J., Jr., Graham D. Y., Lee C. H. 1993. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a gene encoding an adhesin subunit protein of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 175:674–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans D. J., Jr., Evans D. G. 2000. Helicobacter pylori adhesins: review and perspectives. Helicobacter 5:183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferreira Ede O., et al. 2008. The redox potential interferes with the expression of laminin binding molecules in Bacteroides fragilis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 103:683–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fink D. L., Green B. A., St. Geme J. W., III 2002. The Haemophilus influenzae Hap autotransporter binds to fibronectin, laminin, and collagen IV. Infect. Immun. 70:4902–4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fisher M., et al. 2008. Shr is a broad-spectrum surface receptor that contributes to adherence and virulence in group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 76:5006–5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Graslund S., et al. 2008. Protein production and purification. Nat. Methods 5:135–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Groot P. G. D., Sixma J. J. 2007. Perfusion chambers, p. 575–585 In Michelson A. D. (ed.), Platelets, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Burlington, MA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirmo S., Artursson E., Puu G., Wadstrom T., Nilsson B. 1999. Helicobacter pylori interactions with human gastric mucin studied with a resonant mirror biosensor. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ito T., et al. 2008. Helicobacter pylori invades the gastric mucosa and translocates to the gastric lymph nodes. Lab. Invest. 88:664–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawazoe T., et al. 2007. Role of bacterial strain diversity of Helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinogenesis induced by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea in Mongolian gerbils. Helicobacter 12:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langford M. L., Zabaleta J., Ochoa A. C., Testerman T. L., McGee D. J. 2006. In vitro and in vivo complementation of the Helicobacter pylori arginase mutant using an intergenic chromosomal site. Helicobacter 11:477–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee A., et al. 1997. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology 112:1386–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Linden S., Mahdavi J., Hedenbro J., Boren T., Carlstedt I. 2004. Effects of pH on Helicobacter pylori binding to human gastric mucins: identification of binding to non-MUC5AC mucins. Biochem. J. 384:263–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loke M. F., Lui S. Y., Ng B. L., Gong M., Ho B. 2007. Antiadhesive property of microalgal polysaccharide extract on the binding of Helicobacter pylori to gastric mucin. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 50:231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu H., et al. 2007. Functional and intracellular signaling differences associated with the Helicobacter pylori AlpAB adhesin from Western and East Asian strains. J. Biol. Chem. 282:6242–6254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsumoto S., et al. 1997. Induction of ulceration and severe gastritis in Mongolian gerbil by Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 46:391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mecsas J., Rouviere P. E., Erickson J. W., Donohue T. J., Gross C. A. 1993. The activity of sigma E, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible sigma-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev. 7:2618–2628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Necchi V., et al. 2007. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 132:1009–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Odenbreit S., Faller G., Haas R. 2002. Role of the alpAB proteins and lipopolysaccharide in adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Odenbreit S., Kavermann H., Puls J., Haas R. 2002. CagA tyrosine phosphorylation and interleukin-8 induction by Helicobacter pylori are independent from alpAB, HopZ and bab group outer membrane proteins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Odenbreit S., et al. 2009. Outer membrane protein expression profile in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 77:3782–3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Odenbreit S., Till M., Haas R. 1996. Optimized BlaM-transposon shuttle mutagenesis of Helicobacter pylori allows the identification of novel genetic loci involved in bacterial virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 20:361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Odenbreit S., Till M., Hofreuter D., Faller G., Haas R. 1999. Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1537–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Opal S. M., DePalo V. A. 2000. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest 117:1162–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ozbek A., Ozbek E., Dursun H., Kalkan Y., Demirci T. 2010. Can Helicobacter pylori invade human gastric mucosa?: an in vivo study using electron microscopy, immunohistochemical methods, and real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 44:416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raudonikiene A., et al. 1999. Helicobacter pylori with separate beta- and beta′-subunits of RNA polymerase is viable and can colonize conventional mice. Mol. Microbiol. 32:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ringner M., Valkonen K. H., Wadstrom T. 1994. Binding of vitronectin and plasminogen to Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 9:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rokbi B., et al. 2001. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori gene expression within mouse and human gastric mucosae by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR. Infect. Immun. 69:4759–4766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rosa H., Parise E. R. 2008. Is there a place for serum laminin determination in patients with liver disease and cancer? World J. Gastroenterol. 14:3628–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saraswathi V., et al. 2007. Fish oil increases cholesterol storage in white adipose tissue with concomitant decreases in inflammation, hepatic steatosis, and atherosclerosis in mice. J. Nutr. 137:1776–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Selbach M., Moese S., Meyer T. F., Backert S. 2002. Functional analysis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island reveals both VirD4-CagA-dependent and VirD4-CagA-independent mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 70:665–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Semino-Mora C., et al. 2003. Intracellular and interstitial expression of Helicobacter pylori virulence genes in gastric precancerous intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1165–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Senkovich O., Ceaser S., McGee D. J., Testerman T. L. 2010. Unique host iron utilization mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori revealed with iron-deficient chemically defined media. Infect. Immun. 78:1841–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reference deleted.

- 51. Sheu B. S., et al. 2006. Interaction between host gastric Sialyl-Lewis X and H. pylori SabA enhances H. pylori density in patients lacking gastric Lewis B antigen. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Snelling W. J., et al. 2007. HorB (HP0127) is a gastric epithelial cell adhesin. Helicobacter 12:200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tan T. T., Forsgren A., Riesbeck K. 2006. The respiratory pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis binds to laminin via ubiquitous surface proteins A1 and A2. J. Infect. Dis. 194:493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Testerman T. L., Conn P. B., Mobley H. L., McGee D. J. 2006. Nutritional requirements and antibiotic resistance patterns of Helicobacter species in chemically defined media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1650–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Testerman T. L., McGee D. J., Mobley H. L. T. 2001. Adherence and colonization, p. 381–417 In Mobley H. L. T., Mendz G. L., Hazell S. L. (ed.), Helicobacter pylori: physiology and genetics. ASM Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Trust T. J., et al. 1991. High-affinity binding of the basement membrane proteins collagen type IV and laminin to the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 59:4398–4404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tryggvason K. 1993. The laminin family. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5:877–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tzouvelekis L. S., et al. 1991. In vitro binding of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric mucin. Infect. Immun. 59:4252–4254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Valkonen K. H., Ringner M., Ljungh A., Wadstrom T. 1993. High-affinity binding of laminin by Helicobacter pylori: evidence for a lectin-like interaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 7:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Valkonen K. H., Wadstrom T., Moran A. P. 1997. Identification of the N-acetylneuraminyllactose-specific laminin-binding protein of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 65:916–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Valkonen K. H., Wadstrom T., Moran A. P. 1994. Interaction of lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori with basement membrane protein laminin. Infect. Immun. 62:3640–3648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Williams J. C., McInnis K. A., Testerman T. L. 2008. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to abiotic surfaces is influenced by serum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1255–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zerlauth G., Wolf G. 1984. Plasma fibronectin as a marker for cancer and other diseases. Am. J. Med. 77:685–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.