TEXT

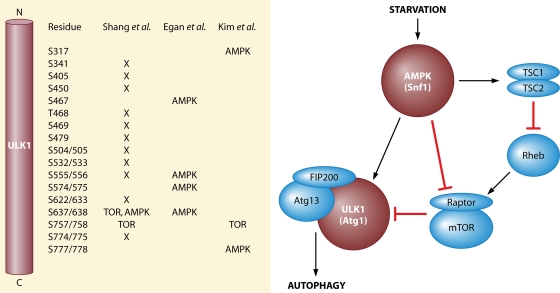

Several recent papers (2, 6, 7, 13) have addressed a new mechanism for the control of mammalian autophagy by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Autophagy describes a family of highly conserved processes whereby cellular constituents are transported to the lysosome for degradation (11, 17). Initially, autophagy was viewed as an essentially random means to recycle cellular materials, for biosynthesis or energy production, under conditions of nutritional deprivation. However, recent work suggests more varied and complex roles for autophagy. First, multiple stimuli besides total starvation can be initiators, and second, some autophagic pathways are selective for particular cargoes. The new studies to be discussed here report that AMPK interacts with, phosphorylates, and activates the ULK1 protein kinase, a key initiator of the autophagic process, and echo earlier results with the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (15). Prior to these reports, AMPK control of mammalian autophagy was thought to be via mTOR. Thus, the new work suggests that two different pathways link AMPK to mammalian autophagy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the control of autophagy. In mammals, the more established mechanism for AMPK regulation of autophagy involves inactivation of the TORC1 pathway upon nutrient deficiency (i) by phosphorylation and activation of TSC2 exchange factor, which in turn will deactivate the Rheb GTPase, and (ii) by phosphorylation of Raptor. Inhibition of TORC1 correlates with increased autophagy. Recent studies raise the possibility of direct control of ULK1 via phosphorylation by AMPK. In addition, TORC1 may negatively regulate ULK1 by phosphorylation. Analysis of the multisite phosphorylation of ULK1 is an ongoing project that needs further exploration. On the left, the present tally of ULK1 phosphorylation sites is linked to the corresponding study (by Shang et al. [13], Egan et al. [2], or Kim et al. [6]) and the protein kinase potentially responsible, where possible. X indicates phosphorylation by an unidentified protein kinase(s). The names of the yeast orthologs of AMPK and ULK1, Snf1 and Atg1, are indicated in parentheses. The ULK1 residue numbers are listed as mouse/human where they differ.

Much of the initial definition of the genes and mechanisms involved in autophagy came from genetic studies of the yeast S. cerevisiae (14), and after subsequent work also with higher eukaryotes, dozens of “autophagy” proteins are now identified (11, 17). The complexity of the process is further underscored by proteomics analyses that link numerous known and putative autophagy-related proteins in protein complexes (1). One of the first autophagy proteins identified in yeast was Atg1 (originally called Apg1), a protein kinase that acts in a complex with Atg13 and Atg17 at an early stage in the induction of autophagy (11). Mammals have two orthologs of Atg1, called ULK1 and ULK2 (UNC-51-like kinases 1 and 2) (10). There is a mammalian ortholog of Atg13, and the ULK complex also contains FIP200, which may functionally be a counterpart of Atg17. As further described below, Atg1/ULK is a key regulator of autophagy from yeast to mammals, and protein phosphorylation events are central to the control of its activity (10).

AMPK, which is widely recognized as a ubiquitous sensor of cellular energy status, responds to an ATP-depleted adenine nucleotide pool by phosphorylating many target proteins with functions related to energy metabolism (4). Since autophagy and AMPK are both stimulated by nutrient deprivation, it would not be surprising if activation of AMPK were connected to increased autophagic activity. However, the first study addressing this possible link reported that the AMPK activator AICAR actually blocked autophagy in hepatocytes (12). The next report connecting autophagy with AMPK addressed S. cerevisiae (15). Mutation of the SNF1 gene, which encodes the yeast ortholog of AMPK, causes a number of defects, including a failure to accumulate glycogen. A genetic screen for the restoration of glycogen storage in snf1 mutants identified ATG1 and ATG13 as genes that enhanced glycogen accumulation in this background. The connection between SNF1, glycogen levels, and autophagy led to the direct demonstration that the Snf1 kinase was a positive regulator of autophagy. Yeast cells actually use the vacuole, the approximate counterpart of mammalian lysosomes, to store some glycogen which is only utilized very late in starvation, possibly for sporulation. Thus, defective autophagy actually decreased long-term glycogen accumulation in yeast. By epistasis, the work of Wang et al. (15) placed Snf1 upstream of Atg1/Atg13 in the regulation of autophagy and glycogen accumulation in yeast (Fig. 1). A few years later, reports began to suggest a similar positive control of autophagy by AMPK also in mammalian cells (9).

The first mechanistic insight into how AMPK might regulate mammalian autophagy invoked control of the mTOR complex 1 (TORC1). The TOR pathway is well known, in both yeast and mammals, to be a negative regulator of autophagy, which is thus enhanced, for example, by treatment with the TORC1 inhibitor rapamycin (16). AMPK was linked to TORC1 control by two separate pathways (Fig. 1). In one pathway, phosphorylation of TSC2 by AMPK would indirectly cause TORC1 inhibition by deactivation of the Rheb GTPase (5). Note that S. cerevisiae lacks TSC2. In the other pathway, phosphorylation of the Raptor component of TORC1 with subsequent recruitment of 14-3-3 proteins would inhibit mTOR activity (3). At this stage, it therefore appeared that AMPK control of autophagy was mechanistically different in mammals and yeast.

This latest work links AMPK and ULK1 in mammalian cells. Egan et al. (2) took a bioinformatics approach in which they sought to identify potential AMPK substrates based on the presence of primary sequence signatures for AMPK sites (3) combined with a screen for proteins that interacted with 14-3-3 proteins. One candidate substrate was ULK1, which, by their analysis, contained four potential AMPK sites. Phosphopeptides corresponding to three of these sites, S555, T574, and S637, were identified by mass spectrometry of ULK1 isolated from cells treated with phenformin, which is known to activate AMPK. Phosphorylation of the other site, S467, was confirmed by use of phosphospecific antibodies. Kim et al. (6) started from the observation that starvation of mammalian cells for glucose caused activation and phosphorylation of mouse ULK1, and they showed that the process was blocked by the AMPK inhibitor compound C. These researchers went on to identify phosphorylation sites in ULK1 by systematic mutagenesis and in vitro phosphorylation, ultimately proposing two main sites of AMPK phosphorylation, S317 and S777. The importance of the sites was validated in cell experiments. A third study, by Lee et al. (7), identified the AMPK γ subunit as a ULK1-interacting protein by mass spectrometric analysis of proteins associated with ULK1 in pulldowns from cells. Lee et al. (7) went on to propose that AMPK-ULK1 interaction is critical for the induction of autophagy and cited unpublished data that AMPK could phosphorylate ULK1 in vitro. Therefore, there would seem to be a satisfying convergence of ideas to formulate a model in which nutritional deprivation activates mammalian AMPK, which phosphorylates and activates ULK1, a key initiator of autophagy (Fig. 1). The scheme fits the earlier genetic data with yeast (15) and is also consistent with the recent description of TORC1-independent autophagy pathways in human cells (8).

The devil, as they say, is in the details. Although the activation of ULK1 by starvation and AMPK is a common theme, the proposed mechanisms differ in their specifics (Fig. 1). The first confusing aspect of the work is that the groups of Shaw and Guan did not identify the same AMPK phosphorylation sites in ULK1. Kim et al. (6) even mutated two of the Shaw sites, S555 and T574, and concluded that they were not targets for AMPK. Matters become more complex with the subsequent study by Shang et al. (13), who reported on ULK1 phosphorylation in human cells, as analyzed by stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) and mass spectrometry. Thirteen phosphorylation sites were identified. Not found were either of the AMPK sites proposed by Kim et al. (6), but S555 and S637 (S556 and S638 in the human sequence) described by Egan et al. (2) were detected. This work strengthens the case that some of the AMPK sites described by Egan et al. (2) are phosphorylated in cells, but the whole thrust of the study by Shang et al. (13) is that nutrient deprivation provokes a massive dephosphorylation of ULK1. The two ULK1 sites most dephosphorylated in response to starvation were S638 and S758, which they consider to be mTOR sites; decreased phosphorylation when TORC1 is inactivated by starvation would seem logical. However, the former is one of the Shaw AMPK sites, and indeed Shang et al. (13) also consider it to be a target for AMPK. One might therefore expect increased phosphorylation upon starvation and activation of AMPK. The other site, S758, was also identified as an mTOR site (S757 in mouse) by Kim et al. (6). However, the two groups differ in their views of the function of S757/758 phosphorylation. Kim et al. (6) argue that the phosphorylation blocks AMPK binding under conditions of nutrient sufficiency so that AMPK is recruited only when TORC1 activity is reduced in starvation, to phosphorylate and activate ULK1. In contrast, Shang et al. (13) consider that dephosphorylation of S758 of ULK1, induced by starvation, leads to dissociation of AMPK from ULK1, with consequent activation of ULK1. One point emerging from the study by Shang et al. (13) is that it may be important to monitor the time course of ULK1 phosphorylation in response to nutritional signals to understand the process fully.

In conclusion, it is surely fair to say that AMPK, ULK1, and mTORC1 interact physically and/or mechanistically and are critical components in the regulation of mammalian autophagy. However, it will obviously require significant further study to clarify the details, especially regarding ULK1 phosphorylation and its interaction with AMPK. As often happens in science, conflicting results may point to unappreciated complexity. What sort of factors might contribute to the observed differences? As noted above, there is an emerging sense that multiple autophagic pathways exist and that there are multiple regulatory inputs. Therefore, some variation in the data could derive from differences in the cells analyzed and the experimental conditions. Also, we should recall that ULK1 is a large protein, multiply phosphorylated in an extensive serine/threonine-rich region of the molecule. Analysis of its phosphorylation status is not a trivial undertaking, even with the application of site-directed mutagenesis, mass spectrometry, and phosphospecific antibodies. Combining different approaches, including analysis of ULK1 phosphorylation in whole animals as well as cultured cells, may also help explain or reconcile the data. One thing is clear: we are likely to see more studies of AMPK/ULK1 control of autophagy in higher eukaryotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Previous related research in my laboratory was supported by NIH grant DK42576.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 May 2011.

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1. Behrends C., Sowa M. E., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W. 2010. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature 466:68–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Egan D. F., et al. 2011. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 331:456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gwinn D. M., et al. 2008. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30:214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hardie D. G. 2007. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inoki K., Zhu T., Guan K. L. 2003. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115:577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim J., Kundu M., Viollet B., Guan K. L. 2011. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:132–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee J. W., Park S., Takahashi Y., Wang H. G. 2010. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PLoS One 5:e15394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipinski M. M., et al. 2010. A genome-wide siRNA screen reveals multiple mTORC1 independent signaling pathways regulating autophagy under normal nutritional conditions. Dev. Cell 18:1041–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meley D., et al. 2006. AMP-activated protein kinase and the regulation of autophagic proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:34870–34879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mizushima N. 2010. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakatogawa H., Suzuki K., Kamada Y., Ohsumi Y. 2009. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:458–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Samari H. R., Seglen P. O. 1998. Inhibition of hepatocytic autophagy by adenosine, aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside, and N6-mercaptopurine riboside. Evidence for involvement of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23758–23763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shang L., et al. 2011. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4788–4793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsukada M., Ohsumi Y. 1993. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 333:169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Z., Wilson W. A., Fujino M. A., Roach P. J. 2001. Antagonistic controls of autophagy and glycogen accumulation by Snf1p, the yeast homolog of AMP-activated protein kinase, and the cyclin-dependent kinase Pho85p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5742–5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124:471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang Z., Klionsky D. J. 2010. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:124–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]