Abstract

Small heat shock proteins (sHsps) are molecular chaperones that protect cells from cytotoxic effects of protein misfolding and aggregation. HspB1, an sHsp commonly associated with senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease (AD), prevents the toxic effects of Aβ aggregates in vitro. However, the mechanism of this chaperone activity is poorly understood. Here, we observed that in two distinct transgenic mouse models of AD, mouse HspB1 (Hsp25) localized to the penumbral areas of plaques. We have demonstrated that substoichiometric amounts of human HspB1 (Hsp27) abolish the toxicity of Aβ oligomers on N2a (mouse neuroblastoma) cells. Using biochemical methods, spectroscopy, light scattering, and microscopy methods, we found that HspB1 sequesters toxic Aβ oligomers and converts them into large nontoxic aggregates. HspB1 was overexpressed in N2a cells in response to treatment with Aβ oligomers. Cultured neurons from HspB1-deficient mice were more sensitive to oligomer-mediated toxicity than were those from wild-type mice. Our results suggest that sequestration of oligomers by HspB1 constitutes a novel cytoprotective mechanism of proteostasis. Whether chaperone-mediated cytoprotective sequestration of toxic aggregates may bear clues to plaque deposition and may have potential therapeutic implications must be investigated in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Molecular chaperones form the first line of defense against protein misfolding in vivo and are therefore key players in neurodegenerative diseases. Members of the small heat shock protein (sHsp) family of chaperones protect cells from intrinsic and extrinsic stresses by antagonizing protein aggregation, regulating cytoskeletal dynamics, and inhibiting apoptosis (23, 45). The human and mouse genomes code for 10 genes for sHsps, sharing 45 to 85% in sequence homology (19, 61). Mice knocked out for HspB1 (also known as Hsp25), a major ubiquitously expressed sHsp, are viable (30), suggesting that HspB1 has a nonessential function for normal development. However, mutations in human HSPB1 (also known as Hsp27) are associated with protein aggregation diseases like Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (17). HspB1 is highly protective against toxicity induced by beta-amyloid (Aβ) (35), αSynuclein (75), or polyglutamine (7, 73), suggesting its importance in protein aggregation diseases.

The sHsps share a conserved α-crystallin domain of 80 to 100 amino acids at their C terminus, whereas their N-terminal regions are variable in sequence and length (4, 41). Many sHsps assemble into dynamic homo- or heteromultimeric complexes composed of 12 to >24 subunits (22, 34), which may be regulated by phosphorylation (26). The main function of sHsps is thought to be binding of misfolded proteins in an ATP-independent manner with a high capacity in order to prevent their aggregation and to hold them in a reactivation-competent state (23, 24, 27). The sHsp-bound misfolded polypeptides may be acted upon by the ATP-dependent chaperones, including Hsp70/Hsp40 and Hsp100 (7, 43), to reactivate the misfolded protein. The bacterial sHsps (IbpA and IbpB) bind overexpressed heterologous proteins and aid in the formation of inclusion bodies (64), suggesting that sHsps may also simply sequester misfolded proteins to prevent cellular damage. However, this possibility has not been investigated in the context of human diseases of protein misfolding and aggregation.

Misfolding and aggregation of proteins are implicated in the dysfunction and degeneration of neurons in many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD). In AD, the high propensity of the beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptide to aggregate is characterized by the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrillar Aβ aggregates in the form of senile plaques (SPs). In addition, soluble Aβ aggregates known as “oligomers” are thought to cause neuronal dysfunction (8, 20, 60). Several transgenic mice expressing familial AD mutants of human amyloid precursor protein (APP) have greatly facilitated the mechanistic understanding of AD. Of relevance to this study are the following mouse lines. (i) Tg2576 mice express the Swedish mutant (K670N and M671L) APP gene under the control of the Prp promoter (28). These mice begin to develop plaque pathology and behavioral deficits by 9 to 11 months of age. (ii) APPswePS1dE9 mice express the Swedish mutant APP humanized mouse gene and the mutant human presenilin-1 (PS1) gene carrying the exon-9-deleted variant (PS1dE9) under independent Prp promoters (31, 32). These mice begin to develop plaque pathology and behavioral deficits by 6 to 9 months of age but do not show significant levels of neurodegeneration at any age.

The importance of sHsps in AD was noted from the observation that HspB1 (Hsp27) and HspB5 (αB-crystallin) were overexpressed in AD brains (51, 52, 57). Interestingly, several sHsps, including HspB1, HspB2, HspB5, HspB6, and HspB8, have been found associated with AD plaques (69, 71, 72). While some sHsps such as HspB1 and HspB5 were observed in the reactive astrocytes, sHsps such as HspB1, HspB2, and HspB6 were observed in the extracellular space in association with plaques in AD brains (72). Loss of HspB5 and HspB2 in Tg2576 mice leads to exacerbation of behavioral deficits, indicating their protective function (47). In vitro, HspB1, HspB6, HspB8, and HspB5 have been observed to mitigate Aβ aggregation and cytotoxicity in Aβ fibrillization experiments (18, 38, 48, 55, 70). Finally, HspB1 was shown to protect cortical neurons against Aβ toxicity (35), suggesting that that it may play a neuroprotective role in AD. However, the mechanism by which sHsps protect cells from the cytotoxicity of protein aggregates is unknown.

Here, using transgenic mouse models and biochemical and cell biological methods, we present evidence that HspB1 is a neuroprotective chaperone that sequesters toxic oligomers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

The antibodies used in this study were as follows. Primary antibodies included mouse monoclonal anti-Aβ (NAB228; Sigma), 1:500 dilution; rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp27/Hsp25 (HspB1; Sigma), 1:200 dilution; rabbit polyclonal anti-αB-crystallin (HspB5; Millipore), 1:500 dilution; and mouse monoclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (anti-GFAP; Dako), 1:100 dilution. Secondary antibodies included goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 or Alexa 555, goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 555 or Alexa 488 (Invitrogen), or goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen).

Purification of recombinant human HspB1.

Human HspB1 cDNA was amplified from the MGC clone ID:21487 (IMAGE:3862626) and subcloned into pNOTAG vector, and sequence was verified. Rosetta cells (Stratagene) were transformed with pNOTAG-HSPB1 to overproduce untagged HspB1 upon addition of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; Sigma). Cells were harvested after 3 to 4 h and lysed in buffer 1 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing 1 mg/ml lysozyme and 20 μg/ml DNase I. The lysate was fractionated in 40% ammonium sulfate. The pellet was redissolved in buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM ammonium chloride, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) and dialyzed against the same buffer. The dialysate was purified on a DEAE-Sepharose column using a gradient of sodium chloride using the Akta chromatography system (GE Health Sciences). Fractions containing HspB1 were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and concentrated using a 10-kDa-cutoff Centricon concentrator (Millipore). The concentrated protein was further separated on a Sephacryl S300 HR26/60 column (GE Health Sciences). This purification procedure resulted in >95% pure HspB1. The protein was dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and concentrated to 5 mg/ml (∼200 μM). Aliquots were flash frozen in a dry-ice-ethanol bath and stored at −80°C. The chaperone function of the purified HspB1 protein was routinely monitored by testing its ability to prevent the aggregation of reduced insulin. Since HspB1 is known to form multimeric structures, only monomer concentrations are mentioned throughout the paper.

Preparation of Aβ unassembled, oligomer, and fibril samples.

Aβ(1–42) peptide was purchased as HFIP (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol)-treated peptide from rPeptide, Athens, GA. Aβ conformers were prepared according to the method of Dahlgren et al. (13). Briefly, 1 mg of Aβ peptide was redissolved in 1 ml HFIP to minimize preexistent aggregates that may influence subsequent steps. This HFIP-treated Aβ was aliquoted (50 μg) and stored as a dried film in a desiccator at −20°C. Just prior to use, the aliquot(s) was redissolved in HFIP and dried into a film in a centrifugal concentrator (Speedvac). To prepare unassembled Aβ, the vacuum-dried peptide was dissolved in 2 μl of anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Acros Organics) to a final concentration of 5.5 mM, followed by dilution with 98 μl of ice-cold 1× PBS to a final concentration of 100 μM, and used immediately. Oligomers were prepared identically to unassembled samples but were incubated at 4°C for 24 h before use. Aβ fibrils were prepared by resuspending the vacuum-dried peptide in DMSO to 5.5 mM, diluting it to 100 μM in 10 mM HCl, and incubating it at 37°C for 24 h. Each conformer of Aβ was incubated for 1 h at 25°C with the indicated concentration of HspB1 or bovine serum albumin (BSA) or with an equivalent volume of 1× PBS. Aβ samples thus prepared were used in the assays described below. For all conformers of Aβ (unassembled, oligomers, or fibrils), only monomeric concentrations are used throughout the paper.

Cell viability.

Cytotoxicity conferred by various aggregates of Aβ (10 μM as monomers) was measured using the N2a (mouse neuroblastoma) cells according to the work of Dahlgren et al. (13). N2a cells were plated at 5,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate in medium containing 10% serum. After 24 h, the attached cells were washed with serum-free medium and were placed in 90 μl of serum-free medium containing N-2 supplements (Invitrogen). To the culture medium, 10 μl of 100 μM Aβ with or without coincubation with HspB1 was added to result in a final concentration of 10 μM Aβ and the indicated concentration of HspB1. Cell viability was measured after 24 h of incubation using CellTiter Blue (Promega).

Inactivation of oligomer toxicity was analyzed by titrating HspB1 concentration, and data (see Fig. 2B) were fitted using Sigmaplot (version 10) to the equation f = min + (max − min)/{1 + 10[(logEC50 − x) ×Hill slope]}, where min is minimum, max is maximum, and EC50 is 50% effective concentration.

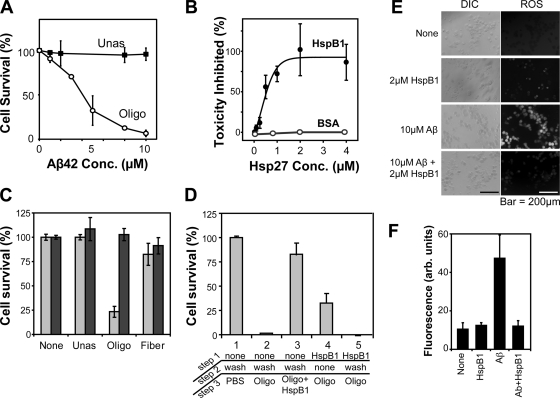

Fig. 2.

HspB1 abolishes toxicity of Aβ oligomers. (A) Dose-response curves for cytotoxicity of the Aβ conformers—unassembled (Unas) and oligomers (Oligo)—on N2a cells. Cell viability was monitored by CellTiter Blue assays. The x axis corresponds to monomer concentrations of Aβ. (B) Titration of HspB1 against Aβ oligomers. Cell viability values at various concentrations of monomeric HspB1 were plotted as the percentage of toxicity inhibited. Toxicity of Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomer) in the absence of HspB1 was set to zero, and cell viability in buffer control was set to 100%. The values were fitted to a ligand binding equation with an R2 of 0.86. (C) N2a cells were treated with 10 μM Aβ conformers—unassembled (Unas), oligomers (Oligo), or fibrils (Fiber)—before (light gray bars) or after (dark gray bars) coincubation with purified human HspB1 (2 μM as monomer). Cells treated with buffer or HspB1 alone (None) had no influence on cell viability. (D) Effect of the order of addition of HspB1 on oligomer-mediated toxicity. The concentrations of all components were identical to those in panel B. The various treatments are numbered 1 to 5, and the treatments are listed in steps 1 to 3. Cells treated with buffer (treatment 1), oligomer (treatment 2), or oligomer coincubated with HspB1 (treatment 3) confirmed the results described in panel B. In treatment 4, cells were first treated with HspB1, followed by the addition of oligomer without washing off the HspB1. In treatment 5, cells were first treated with HspB1, which was washed away prior to oligomer addition. (E) Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in N2a cells was detected using DCFDA fluorescence by microscopy. The left panels show differential interference contrast (DIC) images, and the right panels show fluorescence images (ROS). Incubation of N2a cells with Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomer) alone resulted in the accumulation of ROS in nearly all cells. Treatment of cells with buffer or HspB1 (2 μM as monomer) alone did not induce ROS. Cells treated with oligomers preincubated with HspB1 did not accumulate ROS. (F) Quantitation of data shown in panel E by ImageJ software.

ROS.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was monitored using the ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA; Sigma). N2a cells were treated with 10 μM Aβ oligomers in the absence or presence of 2 μM HspB1 for 4 h. Cells were loaded with DCFDA at a final concentration of 2 μM for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS to remove excess dye and visualized in the green channel using the Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope equipped with fluorescence capability. The DCFDA fluorescence in cells was quantitated using ImageJ software.

Fluorescence and light scattering measurements.

All fluorescence and light scattering measurements were carried out on 300 μl of sample in a quartz cuvette using the Jasco FP-750 spectrofluorometer. For all experiments, Aβ samples (unassembled or oligomer) were at 10 μM (as monomers) in PBS and HspB1 or BSA, when present, was at 2 μM (as monomers). Fluorescence contribution by HspB1 in the absence of Aβ was subtracted from all fluorescence values. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence from HspB1 (note that Aβ has no tryptophans) was measured at 310 to 370 nm (5-nm band-pass) with excitation at 295 nm (5-nm band-pass). The fluorescence spectrum for buffer (PBS) was subtracted from all sample spectra. Thioflavin T (ThT; Sigma) fluorescence was measured after incubating samples with 20 μM ThT for 5 min. Excitation was at 420 nm (10-nm band-pass), and emission was monitored at 450 to 550 nm (5-nm band-pass). Fluorescence intensity values at the ThT emission maximum at 484 nm were recorded. 8-Anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS; Sigma) fluorescence was measured after incubating Aβ samples with or without HspB1 with 10 μM ANS for 5 min. Samples were excited at 370 nm (10-nm band-pass), and emission spectra were recorded between 420 and 570 nm. Fluorescence values for samples without or with HspB1 were corrected for basal fluorescence in buffer (negligible) or in buffer containing 2 μM HspB1 alone, respectively. Light scattering was measured at 350 nm (5-nm band-pass) for 30 min. Samples were mixed at regular intervals (5 min) to prevent settling.

CD.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were measured on a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter using a 0.1-mm quartz sandwich cuvette. Samples contained 100 μM Aβ with or without 20 μM HspB1 in PBS (concentrations refer to monomers in each case). Spectra were recorded between 250 nm and 190 nm with 2-nm band-pass and a scan speed of 60 nm per minute.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM).

Samples (10 μl of 4 μM Aβ ± 0.8 μM HspB1) were applied to freshly cleaved mica disks for 10 min; washed with an excess of filtered, deionized water; and air dried. Samples were not allowed to settle and were briefly mixed prior to placement on mica disks. Samples were visualized using a NanoScope IIIa scanning probe workstation equipped with a MultiMode head and a 12-μm (xy) scanner (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA). Scanning of 0.5- to 2-μm squares was done at a rate between 1 and 3 Hz.

Electron microscopy (EM).

Samples (5 μl of 1 μM Aβ ± 0.2 μM HspB1) were loaded onto carbon-coated copper grids (EM Sciences) and stained with uranyl acetate. Samples were not allowed to settle and were briefly mixed prior to placement on grids. Samples were viewed at 50,000× using a JEM 1230 transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA Inc., Peabody, MA), and images were captured using an UltraScan 4000 (16-megapixel) charge-coupled device (CCD) camera.

Sedimentation.

For examining the sedimentation of HspB1, HspB1 at 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM (as monomers) was incubated with Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomers) and the samples were then subjected to centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were transferred without disturbing the pellet. Pellets were washed with excess buffer to remove any contaminating supernatant. Totals, supernatants, and pellets were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. A similar experiment was carried out with a nonspecific protein like BSA as a control.

Immunofluorescence of purified proteins.

Polylysine-coated cover glasses were coated with Aβ oligomer (10 μM as monomers), HspB1 (2 μM as monomers), or the coincubated mix for 5 min and washed. Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked with 3% BSA, and probed with primary antibodies (mouse monoclonal anti-Aβ NAB228 [1:500; Sigma] and rabbit polyclonal anti-HspB1 [1:200; Sigma] antibodies) followed by secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 555 [both at 1:1,000; Invitrogen]). The coverslips were mounted and viewed using a Zeiss Axio Imager M1 equipped with an Axiocam MR camera. Identical exposure settings were used for all samples. Images were identically processed.

Mice.

Mice used were as follows: (i) 11- to 18-month-old Tg2576 mice (C57B6j × SJL F1 hybrid mice expressing human APP carrying the Swedish mutation; Taconic Farms; n = 3) with corresponding nontransgenic controls (n = 3), (ii) 12- to 18-month-old APPswePS1dE9 mouse [B6.Cg-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9)85Dbo/J; n = 4] brains and corresponding control brains kindly provided by Jerry Buccafusco (deceased), and (iii) HspB1-deficient mice in a C57BL/6 genetic background described in the work of Huang et al (30). Age-matched wild-type mice were used as controls. All mice were maintained in a barrier facility, and all procedures were carried out as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Georgia Health Sciences University.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded fixed thin sections (7 μm) of an AD (73-year-old male) and a normal (54-year-old male) deidentified (anonymous) human hippocampus were purchased from the Biochain Institute. Mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide and transcardially perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Mouse brains were dissected, fixed in paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Coronal sections (10 μm) were cut and placed on glass slides. The sections were deparaffinized and subjected to staining with the following combinations of antibodies: (i) anti-Aβ and anti-HspB1, (ii) anti-Aβ and anti-HspB5, and (iii) anti-HspB1 and anti-GFAP, followed by appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies. The sections were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Imager M1 equipped with an Axiocam MR camera. The exposure settings and image processing for each channel were identical for test and corresponding controls.

RT-PCR.

For gene expression studies, N2a cells (100,000 cells in one well of a 6-well dish) were treated with Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomers) in serum-free medium. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, Aβ was removed by replacing the medium with serum-rich medium. Cells were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells treated identically but without Aβ were used as controls. Cells were harvested, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The RNA quality and integrity were ensured by analyzing the samples on a BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The cDNA was synthesized using the RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen), followed by reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) with a PCR array for mouse stress response genes (Qiagen) using the RT2 quantitative PCR (RT-PCR) SYBR green Master Mix (Qiagen) in a Stratagene Mx3000P RT-PCR system. All procedures were carried out exactly as described in the manufacturer's instructions. The RT-PCR data were analyzed according to instructions provided with the PCR array using the web-based RT2 Profiler (Qiagen) data analysis software.

Primary mouse cortical neurons.

Cortical neurons were cultured from wild-type and HspB1-deficient mice by following a procedure slightly modified from the work of Redmond et al. (50). Briefly, pregnant mice (embryonic day 18) were anesthetized and the embryos were removed into a sterile petri dish containing cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). Embryonic cortices were dissociated using 10 U/ml papain (Worthington), counted, and plated onto poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated plates at a density of 100,000/cm2 in glutamine-free Eagle's basal medium, 1 mM glutamine, 1% N-2 supplement, 5% fetal bovine serum and maintained at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2. This method typically yielded 70 to 80% neurons based on immunofluorescence staining for NeuN. The toxicity of Aβ oligomers was tested as described above for N2a cells.

Statistical analysis of data.

Statistical analysis was carried out by the two-sample Student t test using SigmaStat 3.5 software. Differences were considered significant only when P values were less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Localization of HspB1 in relation to Aβ in vivo.

While plaques are common in AD, they are not thought to be causative of AD. Instead, oligomers are thought to be one of the prime suspects in pathogenesis (44). The fact that HspB1 is an intracellular molecular chaperone capable of protecting neurons against Aβ toxicity (35, 37) encouraged us to examine if its localization into plaques might be due to dead cells, as previously suggested (72). To address this, we utilized the fact that certain transgenic mouse models expressing mutant forms of APP and/or PS1 show minimal cell death although they accumulate numerous plaques in an age-dependent manner (28, 31, 32, 53, 59).

Although HspB1 was previously demonstrated to be associated with AD plaques (72), relative localization of HspB1 and Aβ could not be gleaned from this original study since colocalization experiments were not carried out. Therefore, we first examined the localization of HspB1 and HspB5 (two well-characterized and ubiquitously expressed inducible sHsps) in relation to Aβ in human AD hippocampus sections using immunofluorescence. While there were no plaques detectable in control, numerous plaques were distributed throughout the AD samples as detected by the Aβ-specific antibody. When sections were stained with only secondary antibodies, the nonspecific background staining was minimal in both red and green channels. Both HspB1 and HspB5 were observed in reactive glia surrounding the plaques (Fig. 1A and B), but only HspB1 showed a strong staining in the penumbral area immediately surrounding the Aβ-positive plaques. These observations are in agreement with previous reports (72).

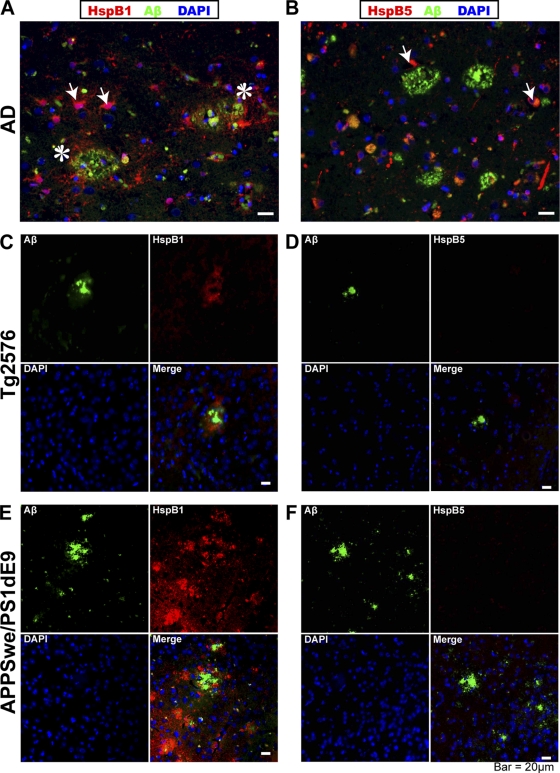

Fig. 1.

Localization of HspB1 in AD and transgenic mouse models of AD. Immunohistochemistry of HspB1 (A, C, and E) and HspB5 (B, D, and F) in AD hippocampal sections (A and B), cortical sections of 12-month-old Tg2576 mice (C and D), and 18-month-old APPswePS1dE9 mice (E and F) to show colocalization with plaques. Colocalization of Aβ (green) and HspB1 or HspB5 (red) with the nuclear stain DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue). The arrows in panels A and B indicate the reactive astrocytes. The asterisks in panel A indicate the penumbral staining of HspB1 (no penumbral staining was observed for HspB5).

Next, we examined the location of mouse HspB1 and HspB5 in relation to the plaques in the brains of two independent AD mouse models, namely, (i) 11- to 18-month-old Tg2576 transgenic mice expressing human APP carrying the Swedish mutations (28) and (ii) 12- to 18-month-old APPswePS1dE9 double transgenic mice expressing a mouse/human chimeric amyloid precursor protein (APP) carrying the Swedish (K670N, M671L) mutation and human presenilin-1 (PS1) carrying the ΔE9 mutation (32). Cortical sections in the coronal plane were prepared from paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue in paraffin blocks. Staining of the sections with only the secondary antibodies without primary antibodies showed no nonspecific fluorescence. Plaques could be detected by their diffuse penumbra in Tg2576 (Fig. 1C and D) and APPswePS1dE9 (Fig. 1E and F) mice but not in the corresponding age-matched nontransgenic control mice (data not shown). The dense core of the plaques was obvious by thioflavin S fluorescence or Congo red birefringence as expected (reference 68 and data not shown). Plaques were numerous in APPswePS1dE9 mice and fewer in Tg2576 mice of similar age, reflecting the faster and more robust plaque development in APPswePS1dE9 mice than in Tg2576 mice. HspB1 was not an abundant protein in the brains of any mice, and its expression was limited to specific motor nuclei as previously reported (2). Interestingly, in both APPswePS1dE9 and Tg2576 mice HspB1 was present in the penumbral area surrounding the plaques but did not significantly overlap with Aβ core of the plaque. On the other hand, HspB5 was not detectable in or around the plaques. Thus, the accumulation of HspB1 around the plaques was not limited to the human AD brain, where extensive neural damage and death occurred, but could also be observed in two independent mouse models with minimal cellular damage. These results suggest that the localization of HspB1 in plaques may be an active, and not a passive, mechanism.

HspB1 prevents Aβ oligomer-mediated toxicity.

Others have observed that sHsps reduce the toxicity of Aβ (18, 38, 48, 55, 70). In these studies Aβ aggregation (amyloid assembly) was carried out in the presence of sHsps, which allows for the chaperoning function of sHsps to affect all Aβ conformers, thereby altering the entire aggregation pathway of Aβ. Oligomeric aggregates of Aβ have been shown to be toxic in both in vitro (14, 33) and in vivo (36, 39, 56) experiments. Thus, the mechanism by which sHsps influence the toxicity of Aβ oligomers, which are thought to be the chief neurotoxic culprits in AD, has not been addressed. Toward this end, we first examined the cytotoxicity of unassembled (freshly dissolved) and oligomeric forms of the 42-residue Aβ peptide (here referred to as Aβ) by monitoring cell viability of N2a (mouse neuroblastoma) cells treated with the Aβ conformers for 24 h (Fig. 2 A). While the oligomeric Aβ showed profound toxicity at higher concentrations (10 μM), as expected from previous studies (13), toxicity was minimal with unassembled Aβ at similar concentrations. This demonstrates the conformation dependence in Aβ toxicity.

To directly examine the effect of HspB1 on Aβ oligomers, we first prepared Aβ oligomers in the absence of sHsps. Next, we examined the effect of HspB1 on oligomer-mediated toxicity by incubating unassembled or oligomeric Aβ with various concentrations of purified human HspB1 protein or bovine serum albumin (BSA; as control) for 1 h followed by testing toxicity on N2a cells as described above (Fig. 2B). Unassembled Aβ showed minimal toxicity before or after coincubation with any concentration of HspB1 or BSA. Cell viability was unaffected by the addition of HspB1 or BSA alone even up to 20 μM (data not shown). Interestingly, the profound toxicity of 10 μM Aβ oligomers was abolished incrementally with increasing concentrations of HspB1 but not BSA (Fig. 1B). The dose-response data were fitted to a ligand-binding curve with an R2 value of 0.86. The EC50 concentration of HspB1 was estimated to be 0.32 ± 0.36 μM and reached a maximum value at 2 μM, suggesting that 5-fold substoichiometric amounts of HspB1 were sufficient to abolish oligomer-mediated cytotoxicity. Larger HspB1 amounts (tested up to 20 μM) maintained the protective effect.

Next, we confirmed the effect of 2 μM HspB1 on unassembled, oligomeric, and fibrillar Aβ (Fig. 2C). The controls—buffer alone or HspB1 alone—showed no decrease in cell viability. The unassembled or fibrillar samples showed a marginal decrease in cell viability, which remained unaffected after incubation with HspB1. The oligomer samples efficiently killed cells in the absence of HspB1, and the brief preincubation with HspB1 completely abolished the cytotoxicity of Aβ oligomers as observed earlier. To ensure that no contaminating protease copurifying with HspB1 was degrading Aβ, we incubated various concentrations of HspB1 with BSA for 24 h and analyzed the samples before and after incubation by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The amounts of BSA before and after incubation with HspB1 remained the same (data not shown), indicating the absence of contaminating proteases in the purified HspB1.

Since it is possible that the protective effect of HspB1 stems from its direct effect on N2a cells rather than on Aβ oligomers, it is important to delineate these possibilities. To investigate the mode of HspB1-mediated protection, we carried out order-of-addition experiments keeping the final concentrations of HspB1 (2 μM) and Aβ (10 μM) constant (Fig. 2D). In step 1, HspB1 protein was either added or not added to N2a cells; in step 2, the added HspB1 was either washed out or not washed out; finally, in step 3, oligomer was added with or without preincubation with 5-fold substoichiometric HspB1. Control proteins (BSA or lysozyme) could not prevent the oligomer toxicity under any conditions (Fig. 2B and data not shown). When no HspB1 was added in step 1, cells were not protected from toxicity unless the oligomers were preincubated with HspB1. When the added HspB1 was not washed off, toxicity was incompletely suppressed, suggesting that the oligomers could elicit some toxicity prior to inactivation by HspB1. When the added HspB1 was washed off prior to oligomer addition, it provided no protection. These results show that the detoxifying effect of HspB1 was directly on oligomers and not by binding to cells.

One of the hallmarks of the cytotoxicity of Aβ oligomers is the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (5). To ensure that the cytoprotective effect of HspB1 also extended to ROS generation, we examined N2a cells using the ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye DCFDA. In agreement with previous studies, we found that treatment of cells with Aβ oligomers resulted in ROS generation. When cells were treated with Aβ oligomers preincubated with HspB1, ROS was not generated (Fig. 2E and F). Addition of HspB1 to culture medium could not block ROS generation when cells were treated with hydrogen peroxide (data not shown). These results suggest that HspB1 inactivated Aβ oligomers and thus prevented the generation of ROS.

Aβ oligomers interact with HspB1.

The fact that HspB1 could profoundly influence the toxicity of Aβ oligomers suggests that it may do so by modulating the oligomers structurally. In order to understand this, we first examined if Aβ conformers interacted with HspB1 by monitoring the structural properties of HspB1 using tryptophan fluorescence. Tryptophan, an intrinsically fluorescent amino acid present in HspB1 but absent in Aβ, is highly useful in detecting conformational changes ensuing from interactions between HspB1 and Aβ conformers. We monitored the tryptophan fluorescence of HspB1 in the absence and presence of unassembled or oligomeric Aβ (Fig. 3 A). The wavelength of maximum Trp fluorescence (λmax) of HspB1 alone peaked at 342 nm. In the presence of either unassembled or oligomeric Aβ, a 4-nm blueshift in λmax to 338 nm was observed. This was coupled with an increase in fluorescence intensity by ∼23% for unassembled Aβ and ∼55% for oligomeric Aβ. These results indicate that (i) HspB1 interacted with the misfolded and unstructured regions of both unassembled and oligomeric Aβ as expected of a chaperone and (ii) the N-terminal region, where 5 of the 6 tryptophans are located (positions 18, 24, 44, 47, and 53), and the beginning of the crystallin domain (position 97) of HspB1 undergo a conformational change upon binding Aβ that may lead to its protection (burial) from the aqueous buffer.

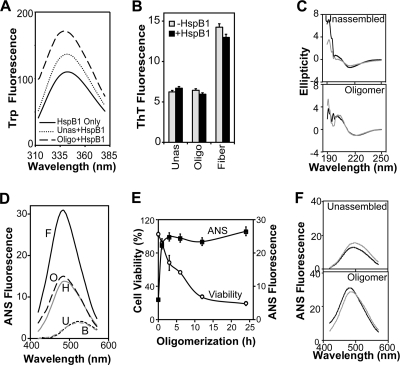

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the effect of HspB1 on Aβ conformers. (A) Interaction between Aβ conformers as indicated (10 μM as monomers) and HspB1 (2 μM as monomers) was monitored by the fluorescence properties of the tryptophans in HspB1. Fluorescence spectra were recorded between 310 and 370 nm after excitation at 295 nm in the absence of Aβ (HspB1 Only) or in the presence of unassembled Aβ (Unas) and oligomers (Oligo). (B) Effect of HspB1 on Aβ conformers was monitored by the amyloid-specific fluorescent dye thioflavin T (ThT; 20 μM). Excitation was at 420 nm, and emission was monitored at 450 to 550 nm. Fluorescence values at 484 nm of samples before (−HspB1) or after (+HspB1) coincubating Aβ conformers (10 μM as monomers) with HspB1 (2 μM as monomers) are plotted. (C) Secondary structural change in Aβ before (gray lines) or after (black lines) coincubation with HspB1 was monitored by circular dichroism spectroscopy between 190 and 250 nm. Ellipticity values shown are mean residue weight molar ellipticity (×1,000) with the unit degree·cm2·dmol−1. (D) Fluorescence studies using an extrinsic fluorophore, ANS, to detect conformational change in Aβ conformers. Aβ peptide was at 10 μM in all samples, and HspB1 was at 2 μM. ANS (10 μM) fluorescence was recorded between 420 and 570 nm after excitation at 370 nm. B, buffer; U, unassembled; O, oligomer; H, HspB1; F, fiber. (E) Kinetics of Aβ oligomer formation was monitored by ANS fluorescence change (y axis on right) and acquisition of cytotoxicity (Viability; y axis on left). (F) Conformational change in the Aβ (10 μM as monomers) and HspB1 (2 μM as monomers) coassemblies was monitored by ANS fluorescence. The actual fluorescence spectra (black lines) of unassembled and oligomer samples preincubated with HspB1 were compared with the expected algebraic sums (gray lines) of the spectra for Aβ and HspB1 collected separately.

Next, we examined the binding of thioflavin T (ThT) to the Aβ conformers with or without HspB1 (Fig. 3B). ThT is a fluorescent dye, which shows increased fluorescence when bound to the cross-beta conformers of amyloid aggregates (40). ThT fluorescence was low in buffer alone or HspB1 alone, and their contributions to the ThT fluorescence of Aβ conformers were subtracted. While unassembled and oligomeric Aβ were similar, with low ThT fluorescence, indicating absence of cross-beta signature, fibrillar Aβ showed higher ThT fluorescence, indicative of cross-beta-sheet conformation as expected. Incubation of any conformer of Aβ with HspB1 resulted in only a negligible change in ThT fluorescence, suggesting that HspB1 did not alter conformations of the unassembled or oligomeric Aβ or the cross-beta-sheets of Aβ fibers.

To probe for secondary structural changes, we carried out circular dichroism spectroscopy studies in the absence or presence of HspB1 (Fig. 3C). The contribution of HspB1 alone was subtracted from the spectra of samples containing both proteins to facilitate comparison. The CD spectra of the Aβ conformers indicated that unassembled and oligomeric Aβ had minimal secondary structure with a low content of β-sheet (<10%) in the absence of HspB1. The spectra showed no change compared to those in the presence of HspB1 after the contribution of HspB1 was subtracted. The similarity in the spectra of Aβ conformers with or without HspB1 indicates that HspB1-Aβ interactions did not result in secondary structural changes in Aβ.

Finally, we examined the tertiary structural features using the fluorescence properties of an extrinsically added fluorophore, anilinonaphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS). ANS fluorescence is very useful in monitoring changes in solvent-exposed hydrophobic pockets in protein complexes (25). The fluorescence of ANS was monitored after addition to buffer alone and unassembled and oligomeric Aβ with or without preincubation with HspB1. ANS fluorescence was exquisitely sensitive to Aβ conformers without preincubation with HspB1 (Fig. 3D). ANS fluorescence in unassembled Aβ samples was similar to that of buffer alone with low intensity and a λmax of 520 nm, suggesting that there were no hydrophobic pockets in unassembled Aβ. On the other hand, oligomeric Aβ showed an ∼4-fold increase over unassembled Aβ in ANS fluorescence intensity with a blueshift in the λmax to 484 nm, suggesting formation of hydrophobic pockets upon oligomer aggregation. Fibrillar Aβ showed a further ∼2-fold increase in intensity over oligomers, but the λmax remained the same. To our knowledge, this advantage of ANS over ThT in detecting oligomers was not previously noted. To understand how the increase in ANS fluorescence relates to the acquisition of toxicity by oligomers, we carried out time course measurements of these parameters (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, while the ANS fluorescence reached maximum in 5 h, maximal cytotoxicity was acquired only after 12 h. This suggests that after reaching stable tertiary structures, oligomers may undergo further structural adjustments before becoming toxic. Both parameters were stable for at least 48 h (data shown till 24 h), indicating the appropriateness of the 24 h of incubation for oligomer generation. To understand whether interaction of the Aβ conformers with HspB1 caused a tertiary structural change, the actual fluorescence spectrum of a sample containing both HspB1 and Aβ was compared to the algebraic sum of the individual spectra (expected spectrum) for HspB1 and Aβ collected separately (Fig. 3F)—a difference is expected for a conformational change. There was no significant difference between actual and expected spectra with unassembled and oligomeric Aβ, indicating that no major tertiary structural changes ensued upon the interaction of HspB1 with unassembled or oligomeric Aβ.

In summary, these studies indicate that binding of HspB1 to Aβ resulted in a conformational change in HspB1 but not in the unassembled or oligomeric Aβ.

HspB1 converts oligomers to large aggregates.

While HspB1 interacted with Aβ and abrogated oligomer toxicity, it appeared not to alter the secondary and tertiary structural features of oligomers. To investigate quaternary structural properties, we examined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) how coincubation with 5-fold substoichiometric HspB1 influences the unassembled or oligomeric Aβ (Fig. 4 A). Unassembled Aβ oligomers and HspB1 were first examined individually by AFM to determine the suitability of this method. Unassembled Aβ appeared as flat 2- to 3-nm-high particles with highly diffuse edges. Oligomeric Aβ appeared as about 5-nm-high and about 5- to 10-nm-wide particles with distinct edges. Purified HspB1 protein appeared as a fairly monodisperse spread of about 10-nm-high and 10-nm-wide particles as expected for the spherical particles of HspB1 and other sHsps from previous studies (7, 54). To investigate the quaternary structural impact of Aβ-HspB1 interactions, we examine unassembled and oligomeric Aβ (10 μM as monomers) before and after preincubation with a 5-fold substoichiometric concentration of HspB1 (2 μM as monomers). In unassembled Aβ coincubated with HspB1, the ∼10-nm particles of HspB1 were prominent with relatively flat unassembled Aβ peptide interspersed through the field. On the other hand, when oligomers were incubated with HspB1, most of the 5- to 10-nm particles disappeared and very large (100- to 200-nm) particles appeared. The size of these large particles showed a ∼23-fold increase in height and a ∼41-fold increase in area in comparison to oligomers alone (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that abrogation of oligomer toxicity by HspB1 correlates with conversion of oligomers into large aggregates.

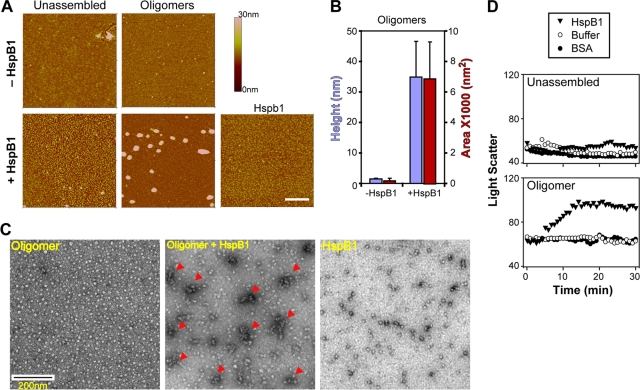

Fig. 4.

Oligomers are converted to large aggregates by HspB1. (A) Atomic force microscopy images of unassembled Aβ and oligomers before (−HspB1) and after (+HspB1) coincubation with HspB1. Each field of view is 2 μm by 2 μm. The color bar on the right indicates the height of the particles. Bar, 500 nm. (B) The AFM images for oligomers without HspB1 and with HspB1 were analyzed for the height (blue) and area (red) of particles. (C) Electron microscopy of oligomers, oligomer coincubated with HspB1, and HspB1. The arrowheads in the middle panel indicate the large aggregates. (D) Kinetics of interaction between Aβ and HspB1 was monitored by light scatter. Light scatter of unassembled or oligomer samples of Aβ (10 μM as monomers) was examined at 350 nm (5-nm band-pass) in the absence (Buffer) or presence of 2 μM BSA or presence of 2 μM HspB1.

To confirm our observations, we examined oligomer samples with or without preincubation with HspB1 using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 4C). Samples with oligomers alone had 5- to 10-nm particles distributed throughout the field and retained very little stain as expected from their flat shape (Fig. 4A and B). Samples with HspB1 alone showed an even distribution of ∼10-nm spherical particles as expected from previous studies (7, 54). When the oligomers were incubated with HspB1, large irregular structures of 100 to 200 nm were prominent. Additionally, the patterns seen in samples containing only HspB1 interspersed the large aggregates, whereas the pattern seen in samples containing only oligomers was less evident. These results suggest that each HspB1 particle potentially sequestered many oligomer particles to form the large aggregates.

To understand the kinetics of the formation of high-molecular-weight aggregates of oligomers and HspB1, we carried out light scattering studies (Fig. 4D). Control samples (HspB1 or BSA not containing Aβ) showed very low light scatter, comparable to that of buffer alone (data not shown). Light scattering by freshly dissolved unassembled Aβ was unaffected by the addition of HspB1 or a nonspecific protein like BSA. Interestingly, light scattering by oligomeric Aβ increased ∼70% after the addition of HspB1 over a period of 15 to 20 min. This increase was not observed when BSA was added or in samples containing oligomers alone. These results suggest that HspB1 and Aβ oligomers readily interacted to form large aggregates.

HspB1 participates in oligomer sequestration.

If HspB1 sequesters oligomers into aggregates, then it is expected to partition into the insoluble fraction in a stoichiometric manner. To address this question, we examined sedimentation of HspB1 at 0.5, 1, and 2 μM in the absence or presence of 10 μM Aβ oligomers into insoluble (pellet) or soluble (supernatant) fractions (Fig. 5 A). Total, supernatant, and pellet fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. In the absence of Aβ oligomers, no HspB1 was detected in the pellet fraction and the same amounts of HspB1 were observed in the total and supernatant fractions, indicating that HspB1 was completely soluble on its own. When HspB1 was coincubated with 10 μM oligomeric Aβ, the amount of soluble HspB1 decreased dramatically with a concomitant appearance in the pellet fractions, indicating its presence in the insoluble aggregates. A nonspecific protein like BSA remained fully soluble at all concentrations in the absence or presence of oligomers (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the amounts of HspB1 in the pellet were similar (approximately 0.5 μM) regardless of the initial concentration, suggesting that the HspB1 fraction that interacted with 10 μM Aβ oligomers was the same at all concentrations. These results demonstrate that the concentrations of HspB1 required to fully abolish oligomer toxicity (Fig. 2B) and to sequester oligomers into nontoxic aggregates were similar.

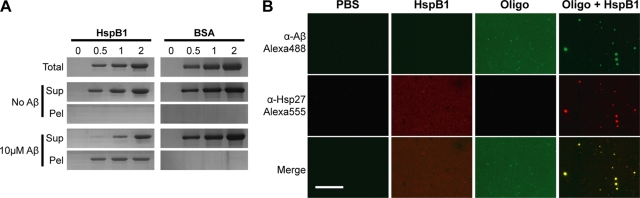

Fig. 5.

Participation of HspB1 in sequestering oligomers into aggregates. (A) Participation of HspB1 or BSA in aggregate formation was analyzed by centrifugation. Various concentrations (0.5, 1, or 2 μM as monomers) of HspB1 or BSA in the absence or presence of Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomers) were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Uncentrifuged samples (Total), supernatants (Sup), and pellets (Pel) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Colocalization of Aβ and HspB1 in the aggregates. HspB1, Aβ oligomers, or oligomer-HspB1 aggregates (prepared as described for Fig. 2) were bound to polylysine-coated glass coverslips and probed with anti-Aβ (green) and anti-HspB1 (red). Bottom panels show merged images, with yellow showing colocalization. Bar, 80 μm.

To confirm the presence of Aβ and HspB1 within the same aggregates, we carried out an immunofluorescence experiment and observed for colocalization of Aβ and HspB1 in the aggregates by light microscopy. Aβ oligomers, HspB1, or a coincubated mixture was deposited on polylysine-coated glass coverslips, fixed using paraformaldehyde, and subjected to immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B). Controls without using primary antibodies produced no staining. Diffuse staining with the anti-Aβ, but not anti-HspB1, antibody was observable in samples containing only Aβ oligomers. Similarly, in samples containing HspB1 alone, anti-HspB1, but not anti-Aβ, produced diffused staining. Neither primary antibody stained samples without Aβ and HspB1 (buffer control). In samples containing Aβ-oligomer-HspB1 aggregates, both anti-Aβ and anti-HspB1 antibodies produced a punctate pattern with numerous small dots (<1 μm) to few large dots (∼5 μm) per field of ∼116 μm by ∼87 μm. The apparent sizes of the particles in light microscopy could be due to the binding of primary and secondary antibodies. However, the smaller of the particles approximately match those observed in AFM and electron microscopy (EM) studies (100 to 200 nm). Interestingly, there was a complete overlap of the punctate pattern in the two channels, clearly demonstrating the presence of both Aβ and HspB1 in the aggregates.

Thus, our results demonstrate that substoichiometric levels of HspB1 sequester Aβ oligomers into large aggregates without significantly altering their conformation and abolish their cytotoxicity.

Importance of cellular HspB1 in Aβ-mediated toxicity.

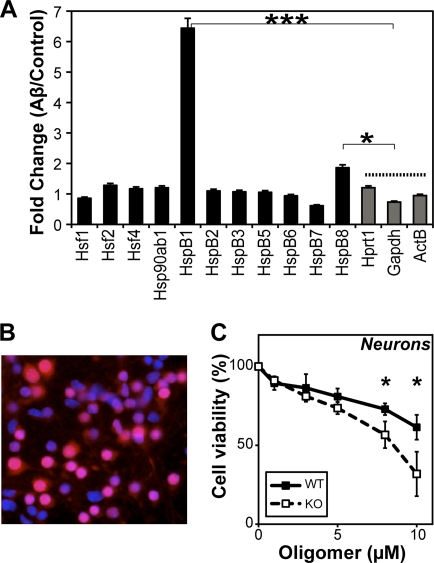

To understand whether cellular HspB1 protects against Aβ-mediated toxicity, we first examined the expression of molecular chaperones using an RT-PCR array for stress response genes in N2a cells treated with Aβ oligomers. For the sake of simplicity, we have presented the data for 7 sHsps (HspB1, -B2, -B3, -B5, -B6, -B7, and -B8), Hsp90, and the heat shock transcription factors (Hsf1, Hsf2, and Hsf4) along with three housekeeping genes (Hprt1, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH], and β-actin) (Fig. 6 A). N2a cells were treated with Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomers) in serum-free medium for 1 h, after which Aβ was removed to prevent toxicity by replacing the medium with serum-containing medium. As a control, cells were mock treated without Aβ. After 2 h of incubation without Aβ, cells were harvested and RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The fold change in expression of Aβ-treated cells versus control cells is shown (Fig. 6A). HspB1 was the most inducible sHsp, showing an ∼6-fold increase in expression after Aβ treatment compared to control. HspB8 also showed an ∼1.8-fold increase in expression. Expression of other chaperones such as Hsp90, Hsp70s, and Hsp40s did not change. These results suggest that Aβ oligomers induce the expression of HspB1 and HspB8, both of which modulate Aβ toxicity. Further, the Aβ-oligomer-induced cellular stress was distinct from the heat shock response, where the expression of Hsp90, Hsp70s, and some Hsp40s is expected.

Fig. 6.

Importance of cellular HspB1 in Aβ toxicity. (A) Fold change in the expression of sHsps (7 out of 10 homologs, HspB1, -2, -3, -5, -6, -7, and -8), heat shock transcription factors (Hsf1, Hsf2, and Hsf4), Hsp90ab1, and housekeeping genes (Hprt1, GAPDH, and ActB) as monitored by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). N2a cells were treated with Aβ oligomers (10 μM as monomers) for 1 h, after which Aβ was removed by replacing the medium. Cells were incubated in serum-rich medium for an additional 2 h, and RNA was extracted. As control, cells were treated identically but without Aβ addition. Fold changes in gene expression between Aβ-treated and control cells were plotted. Data were compared against those for the housekeeping genes by two-sample t test, and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. (B) Representative preparation of primary mouse cortical neurons showing an overlay of staining for neuronal marker NeuN (red) and DAPI (blue). Magenta indicates neurons. (C) The toxicity of various concentrations of Aβ oligomers was tested on wild-type (WT) or HspB1-deficient (KO) neurons. Cell viability was measured by CellTiter Blue assay. Data were compared by two-sample t test, and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences.

To investigate the importance of HspB1 in preventing neurotoxicity, we made use of mice deficient for HspB1 (30). Although the HspB1 knockout mice are viable, demonstrating the nonessential (or redundant) role played by HspB1 during development, it is highly likely that HspB1 plays an important role when challenged with proteotoxic stresses such as oligomer-mediated toxicity. We cultured primary cortical neurons from wild-type and HspB1 knockout mice by standard methods. We confirmed that the neuronal cultures had about 70 to 80% NeuN-positive neurons and a small proportion of astrocytes (Fig. 6B). When wild-type and HspB1-deficient neurons were subjected to Aβ oligomers, they showed a concentration-dependent decrease in viability (Fig. 6C). At high oligomer concentrations, HspB1-deficient neurons were significantly more susceptible to Aβ toxicity than were wild-type neurons. While ∼60% of wild-type neurons remained viable at 10 μM Aβ, only ∼30% of HspB1-deficient neurons remained viable. Preincubating Aβ oligomers with a 5-fold substoichiometric concentration of human HspB1 protein completely abolished oligomer toxicity on neurons as observed in N2a cells (Fig. 2).

These experiments demonstrate that the plaque-associated HspB1 plays an important protective role against oligomers by sequestering them into nontoxic aggregates. However, our results do not imply that these sequestered aggregates might eventually become plaques.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have demonstrated that HspB1 localizes to the plaque penumbra in human AD as well as in mouse models. In vitro, substoichiometric levels of the human sHsp, HspB1, abrogate toxicity of Aβ oligomers by sequestering them into large aggregates. In cultured cells, Aβ oligomers induced the expression of HspB1. Finally, cortical neurons deficient for HspB1 showed greater sensitivity to Aβ toxicity. Thus, sequestration of oligomers into large aggregates by HspB1 constitutes a cytoprotective mechanism.

Human HspB1 was first noted to prevent the fibrillization of Aβ(1–42) peptide (37). HspB1 and HspB8 were also found to be effective inhibitors of cerebrovascular toxicity of Aβ (70, 71). When Aβ was ectopically overexpressed intracellularly in the muscle cells of Caenorhabditis elegans, its localization into inclusions together with overexpressed Hsp16.2 (a worm sHsp) correlated with lower Aβ-mediated toxicity (18). Two different sHsps, HspB4 and HspB5, were shown to prevent fibrillization of Aβ and β2-macroglobulin (48), suggesting that sHsps in general may interfere with amyloid aggregation. Many previous studies reported that sHsps prevented fibrillization of Aβ by monitoring ThT fluorescence and cytotoxicity (18, 38, 48, 55, 70). Our findings are in agreement with these findings. Although we have shown that sequestration of oligomers is an important cytoprotective mechanism of HspB1, we do not yet understand how subunit exchange in HspB1 may influence oligomer sequestration.

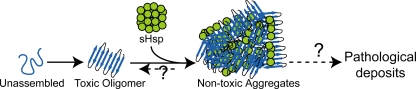

Molecular chaperones protect cells from the deleterious effects of misfolded and aggregated proteins by many different mechanisms: (i) they may stabilize the folded state to prevent misfolding and aggregation, (ii) they may target the misfolded proteins to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, (iii) they may target aggregated proteins for disaggregation and reactivation into functional proteins, and (iv) they may aid in the degradation of aggregates in the lysosome by autophagy (62, 65). Based on our data, we speculate that the sequestration function of HspB1 (or sHsps in general) may constitute a cellular defense against the toxicity of misfolded and aggregated proteins (Fig. 7). Future investigations are required to determine whether such sequestration is related to pathological deposits.

Fig. 7.

Model for the sequestration of toxic oligomers into nontoxic aggregates. Assembly of misfolded proteins (e.g., Aβ) leads to the formation of toxic oligomers as one form of aggregates. Oligomers are thought to cause neuronal dysfunction and death central to neurodegenerative diseases. In this study, we have shown that HspB1 sequesters toxic oligomers into large nontoxic coaggregates and confers neuroprotection. The exact relationship between the large nontoxic aggregates containing HspB1 and Aβ oligomers observed in biochemical studies and HspB1 observed in pathological deposits is currently unknown.

Sequestration of misfolded proteins by HspB1 and other sHsps is essentially an extension of the “holder” function described elsewhere for sHsps (3, 24). This function appears to be conserved from bacteria to humans. In bacteria, when a heterologous protein is overproduced, the sHsps (IbpA and IbpB) bind to the misfolded polypeptides and aid in the formation of inclusion bodies (64), which show amyloid-like properties (6). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it was previously shown that Hsp26 coassembles with thermally denatured proteins into large aggregates to facilitate disaggregation (7). In mammalian cell models, HspB1 is highly protective against toxicity induced by polyglutamine (7, 73) and does so without reducing the aggregation significantly. The sHsps are also commonly present in other inclusions like Lewy bodies and glial cytoplasmic inclusions (12, 63), suggesting that they may play a general role in protecting cells from oligomer-mediated cytotoxicity. An abundance of misfolded proteins may trigger their sequestration by sHsps into aggregates, indicating the importance of sequestration in the molecular mechanism of HspB1. In a yeast model system, toxicity of the Rnq1 protein was protected by the Hsp40 chaperone Sis1 by enhancing aggregation (15). Another Hsp40, DnaJB6, was recently found localized to Lewy bodies and parkinsonian astrocytes (16). These findings, in light of our data, suggest that other chaperones may also sequester misfolded polypeptides and toxic oligomers into inclusions.

The expression of HspB1 in AD brains was elevated in comparison with control human brains (51, 57). We also observed elevated expression of HspB1 around the plaques in transgenic mouse brains. Interestingly, a brief treatment of N2a cells with Aβ oligomers induced the expression of HspB1 and HspB8. Molecular chaperones like HspB1 are overexpressed under the control of the heat shock transcription factor (Hsf1) in response to a variety of stresses, including heat, oxidative, and aging stresses (58, 67). It has been proposed that insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)-mediated signaling pathways regulate the expression of molecular chaperones and other proteostasis regulators in response to an increase in protein misfolding as a result of aging or disease (10, 11). It is possible that increased aggregation of Aβ potentiated increased expression of HspB1 through a combination of various signals, including metabolic changes in astrocytes (1).

Localization of human HspB1 and HspB5 with reactive astrocytes (51, 72) and with degenerating neurons (57) was previously noted in AD brains, and our results concur with these observations. In addition, we also observed a significant amount of HspB1-positive staining in the immediate vicinity (penumbra) of plaques not only in AD brain sections but also in transgenic mouse brain sections. At present, the origin of HspB1 in the plaque penumbra is unknown. However, based on the similar observations that we have made in transgenic mice models where neurodegeneration is limited, we suggest that accumulation of HspB1 at the plaque penumbra may be an active process and may not result from dying cells.

The protection proffered by an intracellular chaperone like HspB1 toward the externally added Aβ oligomer presents a conundrum due to the plasma membrane barrier. This conundrum may be resolved either if Aβ can be internalized into cells or if HspB1 gets externalized. Externalization of HspB1 has been observed in macrophages (49) and B cells (9), but it is unclear whether similar mechanisms exist in neurons or glia. On the other hand, several recent studies have demonstrated that Aβ is readily internalized by a variety of cells, including neuroblastoma cells (29), microglia (42), and astrocytes (1, 46). Moreover, intracellular Aβ is thought to be critical in its cytotoxicity (21, 66, 74). At present, it is unclear where or how HspB1 may encounter Aβ in vivo.

This study underscores the general importance of proteostasis regulators in sequestration as a cellular defense mechanism against protein misfolding. Whether chaperone-mediated sequestration of oligomers facilitates the pathological deposition of plaques and inclusions is a valuable future direction for research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dimitrios Moskophidis for kindly allowing access to HspB1 knockout mice, Jerry Buccafusco (deceased) for kindly providing us with transgenic mouse brains, Mary LaDu for advice on oligomer toxicity, and Bob Smith for help with electron microscopy.

Funding for this work was from the institutional startup support from the Georgia Health Sciences University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allaman I., et al. 2010. Amyloid-beta aggregates cause alterations of astrocytic metabolic phenotype: impact on neuronal viability. J. Neurosci. 30:3326–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong C. L., Krueger-Naug A. M., Currie R. W., Hawkes R. 2001. Constitutive expression of heat shock protein HSP25 in the central nervous system of the developing and adult mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 434:262–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arrigo A. P. 2007. The cellular “networking” of mammalian Hsp27 and its functions in the control of protein folding, redox state and apoptosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 594:14–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arrigo A. P., Landry J. 1994. Expression and function of the low-molecular-weight heat shock proteins, p. 335.In Morimoto R. I. (ed.), The biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butterfield D. A., Boyd-Kimball D. 2004. Amyloid beta-peptide(1–42) contributes to the oxidative stress and neurodegeneration found in Alzheimer disease brain. Brain Pathol. (Zurich, Switzerland) 14:426–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrio M., Gonzalez-Montalban N., Vera A., Villaverde A., Ventura S. 2005. Amyloid-like properties of bacterial inclusion bodies. J. Mol. Biol. 347:1025–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cashikar A. G., Duennwald M. L., Lindquist S. L. 2005. A chaperone pathway in protein disaggregation: Hsp26 alters the nature of protein aggregates to facilitate reactivation by Hsp104. J. Biol. Chem. 280:23869–23875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caughey B., Lansbury P. T. 2003. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26:267–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clayton A., Turkes A., Navabi H., Mason M. D., Tabi Z. 2005. Induction of heat shock proteins in B-cell exosomes. J. Cell Sci. 118:3631–3638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen E., Dillin A. 2008. The insulin paradox: aging, proteotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9:759–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen E., et al. 2009. Reduced IGF-1 signaling delays age-associated proteotoxicity in mice. Cell 139:1157–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dabir D. V., Trojanowski J. Q., Richter-Landsberg C., Lee V. M., Forman M. S. 2004. Expression of the small heat-shock protein alphaB-crystallin in tauopathies with glial pathology. Am. J. Pathol. 164:155–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dahlgren K. N., et al. 2002. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32046–32053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demuro A., et al. 2005. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 280:17294–17300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Douglas P. M., et al. 2008. Chaperone-dependent amyloid assembly protects cells from prion toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7206–7211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Durrenberger P. F., et al. 2009. DnaJB6 is present in the core of Lewy bodies and is highly up-regulated in parkinsonian astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 87:238–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evgrafov O. V., et al. 2004. Mutant small heat-shock protein 27 causes axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 36:602–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fonte V., et al. 2008. Suppression of in vivo beta amyloid peptide toxicity by overexpression of the HSP-16.2 small chaperone protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283:784–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franck E., et al. 2004. Evolutionary diversity of vertebrate small heat shock proteins. J. Mol. Evol. 59:792–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glabe C. G. 2008. Structural classification of toxic amyloid oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 283:29639–29643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gouras G. K., et al. 2000. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 156:15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haley D. A., Horwitz J., Stewart P. L. 1998. The small heat-shock protein, alphaB-crystallin, has a variable quaternary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 277:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haslbeck M. 2002. sHsps and their role in the chaperone network. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:1649–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haslbeck M., Franzmann T., Weinfurtner D., Buchner J. 2005. Some like it hot: the structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:842–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawe A., Sutter M., Jiskoot W. 2008. Extrinsic fluorescent dyes as tools for protein characterization. Pharm. Res. 25:1487–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayes D., Napoli V., Mazurkie A., Stafford W. F., Graceffa P. 2009. Phosphorylation dependence of hsp27 multimeric size and molecular chaperone function. J. Biol. Chem. 284:18801–18807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Horwitz J. 1992. Alpha-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:10449–10453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hsiao K., et al. 1996. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274:99–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hu X., et al. 2009. Amyloid seeds formed by cellular uptake, concentration, and aggregation of the amyloid-beta peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:20324–20329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang L., Min J. N., Masters S., Mivechi N. F., Moskophidis D. 2007. Insights into function and regulation of small heat shock protein 25 (HSPB1) in a mouse model with targeted gene disruption. Genesis 45:487–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jankowsky J. L., et al. 2004. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jankowsky J. L., et al. 2001. Co-expression of multiple transgenes in mouse CNS: a comparison of strategies. Biomol. Eng. 17:157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kayed R., et al. 2003. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300:486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim K. K., Kim R., Kim S. H. 1998. Crystal structure of a small heat-shock protein. Nature 394:595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. King M., Nafar F., Clarke J., Mearow K. 2009. The small heat shock protein Hsp27 protects cortical neurons against the toxic effects of beta-amyloid peptide. J. Neurosci. Res. 87:3161–3175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koffie R. M., et al. 2009. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4012–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kudva Y. C., Hiddinga H. J., Butler P. C., Mueske C. S., Eberhardt N. L. 1997. Small heat shock proteins inhibit in vitro A beta(1–42) amyloidogenesis. FEBS Lett. 416:117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee S., Carson K., Rice-Ficht A., Good T. 2006. Small heat shock proteins differentially affect Abeta aggregation and toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347:527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lesne S., et al. 2006. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440:352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. LeVine H., III 1999. Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 309:274–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. MacRae T. H. 2000. Structure and function of small heat shock/alpha-crystallin proteins: established concepts and emerging ideas. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57:899–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mandrekar S., et al. 2009. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J. Neurosci. 29:4252–4262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mogk A., et al. 2003. Refolding of substrates bound to small Hsps relies on a disaggregation reaction mediated most efficiently by ClpB/DnaK. J. Biol. Chem. 278:31033–31042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murphy M. P., LeVine III H. 2010. Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J. Alzheimers Dis. 19:311–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Narberhaus F. 2002. Alpha-crystallin-type heat shock proteins: socializing minichaperones in the context of a multichaperone network. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:64–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nielsen H. M., et al. 2010. Astrocytic A beta 1–42 uptake is determined by A beta-aggregation state and the presence of amyloid-associated proteins. Glia 58:1235–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ojha J., Karmegam R. V., Masilamoni J. G., Terry A. V., Cashikar A. G. 2011. Behavioral defects in chaperone-deficient Alzheimer's disease model mice. PLoS One 6:e16550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Raman B., et al. 2005. AlphaB-crystallin, a small heat-shock protein, prevents the amyloid fibril growth of an amyloid beta-peptide and beta2-microglobulin. Biochem. J. 392:573–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rayner K., et al. 2008. Extracellular release of the atheroprotective heat shock protein 27 is mediated by estrogen and competitively inhibits acLDL binding to scavenger receptor-A. Circ. Res. 103:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Redmond L., Kashani A. H., Ghosh A. 2002. Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron 34:999–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Renkawek K., Stege G. J., Bosman G. J. 1999. Dementia, gliosis and expression of the small heat shock proteins hsp27 and alpha B-crystallin in Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport 10:2273–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Renkawek K., Voorter C. E., Bosman G. J., van Workum F. P., de Jong W. W. 1994. Expression of alpha B-crystallin in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 87:155–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Richner M., Bach G., West M. J. 2009. Over expression of amyloid beta-protein reduces the number of neurons in the striatum of APPswe/PS1DeltaE9. Brain Res. 1266:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rogalla T., et al. 1999. Regulation of Hsp27 oligomerization, chaperone function, and protective activity against oxidative stress/tumor necrosis factor alpha by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18947–18956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Santhoshkumar P., Sharma K. K. 2004. Inhibition of amyloid fibrillogenesis and toxicity by a peptide chaperone. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 267:147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shankar G. M., et al. 2008. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14:837–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shinohara H., Inaguma Y., Goto S., Inagaki T., Kato K. 1993. Alpha B crystallin and HSP28 are enhanced in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 119:203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sorger P. K. 1991. Heat shock factor and the heat shock response. Cell 65:363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Spires T. L., Hyman B. T. 2005. Transgenic models of Alzheimer's disease: learning from animals. NeuroRx 2:423–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stine W. B., Jr., Dahlgren K. N., Krafft G. A., LaDu M. J. 2003. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-beta peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11612–11622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taylor R. P., Benjamin I. J. 2005. Small heat shock proteins: a new classification scheme in mammals. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 38:433–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tyedmers J., Mogk A., Bukau B. 2010. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Uryu K., et al. 2006. Convergence of heat shock protein 90 with ubiquitin in filamentous alpha-synuclein inclusions of alpha-synucleinopathies. Am. J. Pathol. 168:947–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ventura S., Villaverde A. 2006. Protein quality in bacterial inclusion bodies. Trends Biotechnol. 24:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Voisine C., Pedersen J. S., Morimoto R. I. 2010. Chaperone networks: tipping the balance in protein folding diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 40:12–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wertkin A. M., et al. 1993. Human neurons derived from a teratocarcinoma cell line express solely the 695-amino acid amyloid precursor protein and produce intracellular beta-amyloid or A4 peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:9513–9517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Westerheide S. D., Anckar J., Stevens S. M., Jr., Sistonen L., Morimoto R. I. 2009. Stress-inducible regulation of heat shock factor 1 by the deacetylase SIRT1. Science 323:1063–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Westermark G. T., Johnson K. H., Westermark P. 1999. Staining methods for identification of amyloid in tissue. Methods Enzymol. 309:3–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wilhelmus M. M., et al. 2007. Small heat shock proteins associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy of hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Dutch type) induce interleukin-6 secretion. Neurobiol. Aging 30:229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wilhelmus M. M., et al. 2006. Small heat shock proteins inhibit amyloid-beta protein aggregation and cerebrovascular amyloid-beta protein toxicity. Brain Re. 1089:67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wilhelmus M. M., et al. 2006. Small heat shock protein HspB8: its distribution in Alzheimer's disease brains and its inhibition of amyloid-beta protein aggregation and cerebrovascular amyloid-beta toxicity. Acta Neuropathol. 111:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wilhelmus M. M., et al. 2006. Specific association of small heat shock proteins with the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease brains. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 32:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wyttenbach A., et al. 2002. Heat shock protein 27 prevents cellular polyglutamine toxicity and suppresses the increase of reactive oxygen species caused by huntingtin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:1137–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang Y., McLaughlin R., Goodyer C., LeBlanc A. 2002. Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid beta peptide 1–42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. J. Cell Biol. 156:519–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zourlidou A., Payne Smith M. D., Latchman D. S. 2004. HSP27 but not HSP70 has a potent protective effect against alpha-synuclein-induced cell death in mammalian neuronal cells. J. Neurochem. 88:1439–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]