Abstract

Chloroquine (CQ) is an important antimalarial drug for the treatment of special patient groups and as a comparator for preclinical testing of new drugs. Pharmacokinetic data for CQ in animal models are limited; thus, we conducted a three-part investigation, comprising (i) pharmacodynamic studies of CQ and CQ plus dihydroartemisinin (DHA) in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice, (ii) pharmacokinetic studies of CQ in healthy and malaria-infected mice, and (iii) interspecies allometric scaling for CQ from 6 animal and 12 human studies. The single-dose pharmacodynamic study (10 to 50 mg CQ/kg of body weight) showed dose-related reduction in parasitemia (5- to >500-fold) and a nadir 2 days after the dose. Multiple-dose regimens (total dose, 50 mg/kg CQ) demonstrated a lower nadir and longer survival time than did the same single dose. The CQ-DHA combination provided an additive effect compared to each drug alone. The elimination half-life (t1/2), clearance (CL), and volume of distribution (V) of CQ were 46.6 h, 9.9 liters/h/kg, and 667 liters/kg, respectively, in healthy mice and 99.3 h, 7.9 liters/h/kg, and 1,122 liters/kg, respectively, in malaria-infected mice. The allometric equations for CQ in healthy mammals (CL = 3.86 × W0.56, V = 230 × W0.94, and t1/2 = 123 × W0.2) were similar to those for malaria-infected groups. CQ showed a delayed dose-response relationship in the murine malaria model and additive efficacy when combined with DHA. The biphasic pharmacokinetic profiles of CQ are similar across mammalian species, and scaling of specific parameters is plausible for preclinical investigations.

INTRODUCTION

Chloroquine (CQ) was introduced 50 years ago as an alternative to quinine (25, 70). It became the drug of choice for both prophylaxis and treatment of malaria, but resistance has caused a decline in the contemporary clinical use of chloroquine (25, 35, 40, 70, 72). Nevertheless, CQ remains one of the most important antimalarial drugs, especially in the treatment of vivax malaria and special patient groups, such as children and pregnant women (32, 37, 48, 51, 73), not least because it is inexpensive and well tolerated and has a rapid onset of action. Recent studies have clarified the mechanism of CQ resistance and shown that clinical efficacy of CQ may return at least a decade after it has been withdrawn from use, prompting suggestions that CQ could reemerge as an important therapeutic option for malaria, most likely in combination with artemisinin compounds or chemosensitizing agents (25, 28, 36, 42, 45, 70).

Notwithstanding its clinical status, CQ has a prominent role as a comparator for in vitro and in vivo preclinical testing of new antimalarial drugs (54, 56, 68, 74). Remarkably, there is a paucity of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data for CQ in preclinical animal models, particularly in murine malaria models (4, 11, 29).

The pharmacokinetic parameters for CQ exhibit wide interindividual variation, although limitations in study design and analytical procedures have been contributing factors (18, 64, 65). Recent clinical studies have provided more robust pharmacokinetic parameters for CQ, including data in children and pregnant women (32, 37, 51). CQ apparent clearance (CL/F) and apparent volume of distribution (V/F) data are matrix dependent, due to a high blood/plasma ratio (>5:1), but elimination rate constant (k) and half-life (t1/2) are comparable from blood and plasma pharmacokinetic profiles (18, 35, 65). For example, the clearance of CQ from whole blood and plasma is approximately 0.1 to 0.25 liter/h/kg of body weight and 0.5 to 0.9 liter/h/kg, respectively, in healthy volunteers, and the t1/2 of CQ is 150 to 290 h (17–19, 32, 35, 47, 59). Approximately 30 to 50% of the dose of CQ is converted by hepatic metabolism to the active metabolite, monodesethylchloroquine (DCQ) (18, 59).

Pharmacokinetic studies of CQ in animal models are limited, but data from the more detailed investigations show biphasic elimination, long β-phase half-life, and large volume of distribution (1, 2, 50). As CQ is widely used in preclinical animal studies, we have conducted a three-component investigation, comprising (i) pharmacodynamic studies of single- and multiple-dose CQ, and a single-dose combination of dihydroartemisinin (DHA) plus CQ, in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice; (ii) pharmacokinetic studies of CQ in control and P. berghei-infected mice; and (iii) an interspecies allometric analysis of pharmacokinetic parameters for CQ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain was obtained from the Department of Microbiology, Royal Perth Hospital, Australia. CQ diphosphate (C18H26ClN3 · 2H3PO4; molecular weight, 515.9; molecular weight of anhydrous CQ = 319.9) and amodiaquine hydrochloride (AQ; internal standard for high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC] analysis) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd., Castle Hill, Australia. Monodesethylchloroquine dioxalate was manufactured by Starks Associates (Buffalo, NY). Piperaquine phosphate (PQ; internal standard for HPLC analysis) was obtained from Yick-Vic Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals, Kowloon, Hong Kong. Sodium pentobarbitone for injection (30 mg/ml sodium pentobarbitone, 40% [vol/vol] propylene glycol, and 10% [vol/vol] ethanol in water [pH 9.5]) was prepared in-house and diluted 50:50 with 0.9% (wt/vol) sodium chloride for injection prior to use. All general laboratory chemicals and solvents were of analytical or HPLC grade, as appropriate (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd., Castle Hill, Australia; BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, United Kingdom; and Merck Pty Ltd., Kilsyth, Australia).

Mice.

These studies were approved by the Curtin University Animal Ethics Committee. Male Swiss mice (5 to 6 weeks old; average weight, 29.4 ± 2.1 g) were obtained from the Animal Resource Centre (Murdoch, Australia). Male BALB/c mice (7 to 8 weeks old; Animal Resource Centre) were used for weekly passage of malaria parasites. Animals were housed at 22°C under a 12-h light-dark cycle with free access to sterilized commercial food pellets (Glen Forrest Stockfeeders, Perth, Australia) and sterilized, acidified water (HCl; pH 2.5) to prevent bacterial infections (62).

Parasites.

Plasmodium berghei ANKA parasites (Australian Army Malaria Research Institute, Enoggera, Australia) were maintained by continuous weekly blood passage in BALB/c mice. A standard inoculum of 107 parasitized erythrocytes per 100 μl was prepared by dilution of blood harvested from BALB/c mice (>30% parasitemia) in citrate-phosphate-dextrose solution (39) and administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection to infect experimental (Swiss) mice.

Parasite enumeration in infected mice.

Peripheral blood smears were prepared with blood obtained from the tail veins of infected mice. The thin films were fixed in methanol (3 min) and then stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain using a Hema-Tek staining machine (Ames Co., Elkhart, IN). Blood smears were examined by oil immersion light microscopy at ×100 magnification (Leica DMLS light microscope; Leica Microsystems, Gladesville, Australia). The parasitemia was determined by counting 30 or 100 fields of view for >0.5% and <0.5% infected erythrocytes, respectively, thus ensuring a limit of detection on the order of 0.002% parasitemia. Tail vein bleeds were performed at least twice daily until the time of euthanasia (>40% parasitemia, >10% reduction in mouse body weight in less than 24 h, or termination of the experimental protocol). Mice were euthanized by sodium pentobarbitone injection (50 to 100 mg/kg i.p.).

Drug treatment and pharmacodynamic study.

CQ diphosphate is freely soluble in aqueous media, and solutions have a pH of about 4.5. CQ solutions were prepared by dissolving CQ diphosphate in water (approximately 30 mg/ml) and diluting it to the required concentration for a standard 100-μl injection volume. The solution was filtered prior to injection (Millex-HV 0.45-μm filter unit; Millipore, Molsheim, France).

Based on previous reports (9, 11, 13) and a pilot study (data not shown), CQ doses of 0, 300, 600, 900, and 1,500 μg CQ (approximately 0, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/kg, respectively, for a 30-g mouse) were selected for the dose ranging studies. The CQ solutions were administered to each mouse by i.p. injection, 64 h after inoculation with 107 P. berghei-parasitized erythrocytes (anticipated parasitemia of 3 to 5%, confirmed by microscopy). Treatment groups comprised 9, 7, 9, and 7 mice for 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/kg CQ, respectively, while the control group comprised 4 mice.

In the multiple-dose studies, two dosage strategies that delivered a total dose of 1,500 μg CQ (50 mg/kg) were compared (n = 8 per group). The first regimen comprised three doses, 20 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg CQ, at 12-hourly intervals. As P. berghei has a 24-h erythrocytic cycle (compared to 48 h in the principal human malarias), this dose interval had temporal similarity to a once-daily dose in humans. The second dose regimen comprised five doses of 10 mg/kg at 12-hourly intervals. In both multiple-dose regimens, the first dose was administered 64 h after parasite inoculation.

In the combination study, mice (n = 8) received single i.p. doses of 30 mg/kg DHA and 30 mg/kg CQ, 64 h after inoculation (DHA was dissolved in a 60:40 mixture of dimethyl sulfoxide and polysorbate 80). The doses of DHA and CQ were shown previously (23) and in the present study to be subtherapeutic, with peripheral parasitemia above detectable limits throughout the course of the study, thus facilitating a comparison of the single doses and the drug combination.

Pharmacokinetic study.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for CQ and DCQ were determined from 125 uninfected male Swiss mice (6 weeks old; mean weight, 33.8 ± 2.8 g) and 125 malaria-infected mice (31.7 ± 2.9 g; inoculated with 107 P. berghei parasites and given CQ 64 h later, at which time the mean parasitemia was 3.2% ± 1.3%). CQ was administered i.p. at a single dose of 1,500 μg (approximately 50 mg/kg CQ). Mice were anesthetized with 50 to 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbitone 5 to 10 min prior to blood collection. Blood was harvested from groups of mice (n = 5) by cardiac puncture at 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 min; 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 8, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, and 56 h; and 3, 4, 5, and 7 days into 1-ml lithium heparin tubes (Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and the plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for CQ and DCQ measurement (31). A peripheral blood film was prepared from each mouse prior to CQ dosing and at the time of euthanasia to confirm that the parasitemia data in the pharmacokinetic study mice were consistent with the pharmacodynamic study (data not shown).

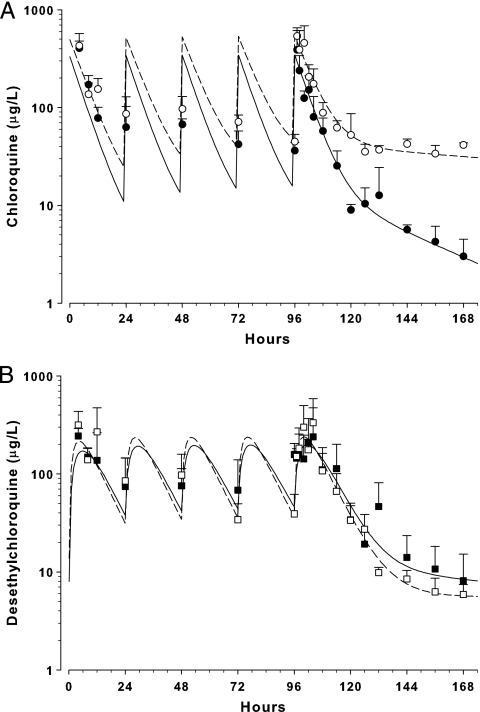

The pharmacokinetic properties for CQ and DCQ were also determined in a multidose study of 125 uninfected male Swiss mice (30.8 ± 3.1 g) and 125 malaria-infected mice (29.2 ± 3.1 g; inoculated with 107 P. berghei parasites and given CQ 64 h later; mean parasitemia = 2.8% ± 1.4%). Five doses of 1,500 μg (50 mg/kg) i.p. CQ were administered at 24-h intervals (these doses were used to extend survival of the mice). Blood was harvested from groups of mice (n = 5) by cardiac puncture at 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after the first dose; 24 h after the second, third, and fourth doses; and then 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 18 h after the fifth dose and at 5, 5.25, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 8, 10, 15, 21, and 30 days after commencement of the dosage regimen. The blood was processed for CQ and DCQ measurement by HPLC and for peripheral blood films as described above. In addition, a peripheral blood film was prepared each day from mice in the last two cohorts (21 and 30 days; n = 10) to assess the pharmacodynamic response to the five-dose 50-mg/kg/dose regimen.

HPLC analysis.

Stock solutions of CQ and DCQ (1-g/liter base) were prepared separately, and two internal standards (AQ and PQ) were used, to counter any interference in the analysis. A 5-point linear calibration curve was prepared, using blank human plasma, and quality control samples (5 μg/liter and 50 μg/liter) were included for each analytical batch. CQ and DCQ extraction from plasma was based on our established method (31). Briefly, plasma standards and samples (500 μl) were spiked with internal standard (PQ, 200 ng, and AQ, 200 ng), mixed with 5 ml of t-butylmethyl ether and 200 μl of 5 M NaOH, and then manually shaken for 10 min. All tubes were centrifuged (1,500 × g) for 10 min, and 4.5 ml of the organic phase was then transferred into clean tubes and back-extracted into 0.1 ml of 0.1 M HCl by shaking for 5 min. This procedure was followed by centrifugation for 10 min (1,500 × g), and the organic layer was aspirated to waste. The HCl layer was transferred to a clean glass tube and centrifuged (1,500 × g) for 20 min, after which 60-μl aliquots were injected onto the HPLC column.

Separation was performed on a Gemini C6-phenyl 110A (150- by 4.6-mm, 5-μm) HPLC column connected to a Gemini C6-phenyl (4- by 3-mm) guard column (Phenomenex, Lane Cove, Australia) at 30°C. The mobile phase comprised 0.05 M KH2PO4 (pH 2.5) and 13% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, with a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and analytes were detected by UV absorbance at 343 nm. The approximate retention times for PQ, DCQ, CQ, and AQ were 2.5, 4.2, 5.2, and 6.8 min, respectively.

The intraday relative standard deviations (RSDs) for CQ were 7.8, 4.2, and 3.6% at 5 μg/liter, 500 μg/liter, and 3,000 μg/liter, respectively (n = 5), while interday RSDs were 8.3, 5.8, and 5.2% at 5 μg/liter, 500 μg/liter, and 3,000 μg/liter, respectively (n = 25). The intraday RSDs for DCQ were 6, 4.9, and 3.4% at 5 μg/liter, 100 μg/liter, and 1,000 μg/liter, respectively (n = 5), while interday RSDs were 7.9, 6.3, and 5.4% at 5 μg/liter, 100 μg/liter, and 1,000 μg/liter, respectively (n = 25). The limits of quantification and detection were 1.2 μg/liter and 0.6 μg/liter for CQ and 1 μg/liter and 0.5 μg/liter for DCQ, respectively.

Allometric scaling.

A detailed literature search for pharmacokinetic studies of CQ in mammals was performed. Where necessary, estimates of the parameters of interest (t1/2 and clearance) were determined using model-independent pharmacokinetic calculations. Regression analysis of the log-transformed data was used to determine the coefficient (a) and exponent (b) for the simple allometric equation Y = a × Wb, where Y is the pharmacokinetic parameter and W is body weight (20, 41, 60). Interspecies scaling of half-life included all available data from malaria-infected and control subjects. However, due to the high blood/plasma ratio of CQ (18, 65), scaling of clearance and volume of distribution comprised only the plasma data.

Statistical and pharmacokinetic analyses.

Data analysis and representation were performed with SigmaPlot version 11 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Data are means ± standard deviations (SDs) unless otherwise indicated. The Student t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison of groups as appropriate, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

For pharmacokinetic modeling, measured plasma concentrations were normalized to a dose of 50 mg/kg CQ, according to the weight of each mouse at the time of dosing. Consistent with the principles of destructive testing (5, 75), the mean normalized plasma concentration for each group of mice was used to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters. Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using Kinetica version 5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA). Noncompartmental analysis of the plasma concentration-time data was used to estimate area under the curve (AUC0–∞; log-linear trapezoidal method), Cmax (maximum plasma concentration), tmax (time of maximum plasma concentration), t1/2, CL/F, and V/F of CQ, and the AUC0–∞, Cmax, tmax, and t1/2 of DCQ, for the single-dose data. The metabolic ratio of DCQ to CQ in control and malaria-infected mice was calculated from AUC0-∞ data, corrected for molecular weight. A two-compartment model provided the best fit to the data to estimate pharmacokinetic descriptors for the observed biphasic elimination of CQ (t1/2α and t1/2β; weighting = 1/y2). A two-compartment model (weighting = 1/y2) with first-order absorption was fitted to the DCQ plasma concentration-time data to estimate the formation rate constant (DCQ from CQ; kF).

RESULTS

Pharmacodynamic study.

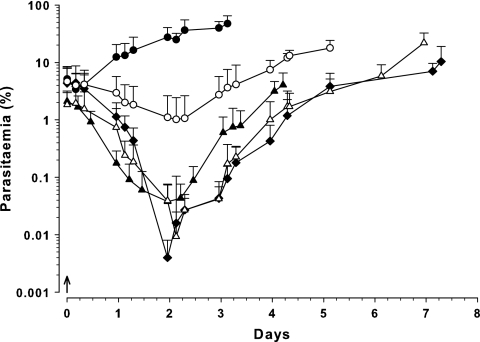

Administration of a single dose of CQ resulted in a decline in parasitemia at all doses tested (Fig. 1). At 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/kg CQ, the parasitemia fell to a nadir of 1%, 0.04%, 0.008%, and 0.004%, respectively, approximately 2 days after the dose. The parasitemia then increased until the experimental endpoints were reached, with median (range) survival times of 6 (5 to 8), 4 (3 to 5), 6 (5 to 11), and 8 (6 to 11) days for the 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/kg CQ dose groups, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Parasitemia-time profile in Swiss mice following administration of single i.p. doses of CQ (↑) administered 64 h after inoculation with 107 P. berghei-parasitized erythrocytes. Data are shown as total parasitemia (log scale; mean percentage of erythrocytes infected ± SD), commencing from the time of CQ administration. Symbols: ●, control (n = 4); ○, 10 mg/kg CQ (n = 9); ▴, 20 mg/kg (n = 7); ▵, 30 mg/kg (n = 9); ◆, 50 mg/kg (n = 7).

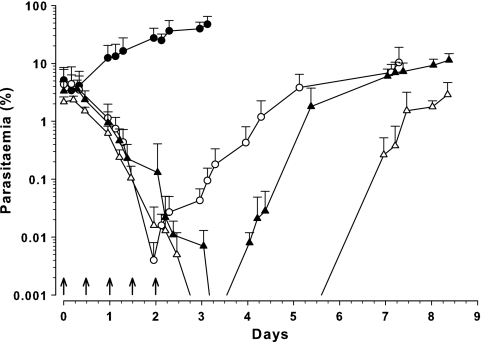

Mice receiving the 3-dose regimen (20, 20, and 10 mg/kg CQ, 12 h apart) showed a significant decrease in parasitemia, falling below the limit of detection approximately 3 days after the initial dose and remaining undetected for at least 12 h (Fig. 2). Parasite nadir was estimated by extrapolation to occur 74 h after the initial dose of CQ, at a parasitemia of 0.0005%, and the median (range) survival time was 7 (6 to 10) days. The five-dose 10-mg/kg/dose series also showed a sustained decrease in parasitemia, falling below the limit of detection approximately 66 h after the first dose and remaining undetectable for more than 2 days (Fig. 2). The median survival time in this group was 9 (7 to 16) days.

Fig. 2.

Parasitemia-time profile in Swiss mice following administration of either a single i.p. dose of 50 mg/kg CQ (↑; 0 days), a three-dose regimen (20, 20, and 10 mg/kg at 0, 0.5, and 1 day, respectively; ↑), or a five-dose regimen (5 doses of 10 mg/kg at 12-hour intervals; ↑) with the first dose administered 64 h after inoculation with 107 P. berghei-parasitized erythrocytes. Data are shown as total parasitemia (log scale; mean percentage of erythrocytes infected ± SD). Symbols: ●, control (n = 4); ○, 50-mg/kg CQ single dose (n = 7); ▴, 3-dose regimen (n = 8); ▵, 5-dose regimen (n = 8).

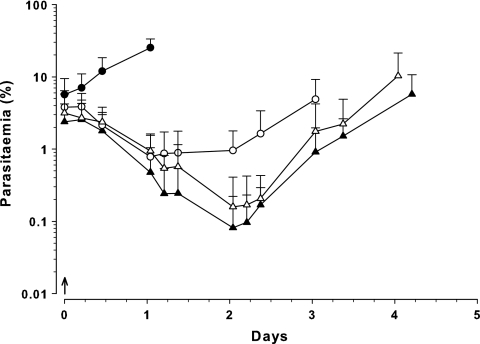

Single-dose DHA (30 mg/kg) and CQ (30 mg/kg) and the DHA-CQ combination showed a prompt decrease in parasitemia to parasite nadirs at 25 h (0.8%), 49 h (0.16%), and 49 h (0.08%), respectively (Fig. 3). The nadir parasitemia for DHA-CQ was significantly lower than that for DHA alone (P = 0.004; t test) and suggested an additive effect.

Fig. 3.

Parasitemia-time profiles in Swiss mice following single i.p. administration of 30-mg/kg DHA (○; n = 9) or 30-mg/kg CQ (▵; n = 12), concurrent doses of 30 mg/kg DHA plus 30 mg/kg CQ (▴; n = 8), and vehicle as control (●; n = 4). All doses (↑) were administered 64 h after inoculation with 107 P. berghei-parasitized erythrocytes. Data are shown as total parasitemia (log scale; mean percentage of erythrocytes infected ± SD).

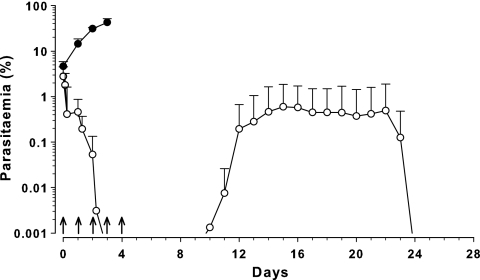

In mice that received five 50-mg/kg doses of CQ (from the pharmacokinetic study), a prompt decline in mean parasitemia was observed, falling below the limit of detection after the third dose (Fig. 4). Parasites remained undetectable for a further 7 days, and recrudescence was observed 10 days after the initial dose. From 14 to 21 days, the mean parasitemia remained relatively stable (0.37 to 0.59%) and then steadily decreased until becoming undetectable 24 days after the initial CQ dose.

Fig. 4.

Parasitemia-time profile in Swiss mice (○; n = 10) following administration of five 50-mg/kg doses of CQ at 24-hourly intervals (↑), with the first dose administered 64 h after inoculation with 107 P. berghei-parasitized erythrocytes. Data are shown as total parasitemia (log scale; mean percentage of erythrocytes infected ± SD). ●, control (n = 4).

Pharmacokinetic study.

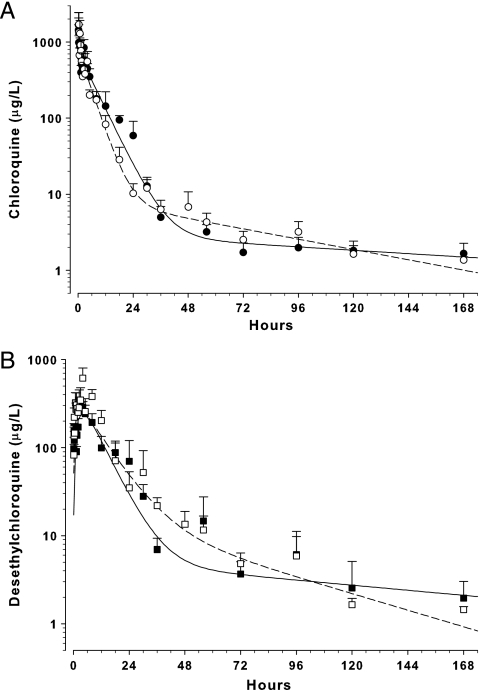

The plasma CQ and DCQ concentration-time profiles following a single dose and multiple doses of CQ are shown in Fig. 5 and 6. The Cmax, tmax, elimination t1/2, CL/F, and V/F of CQ were 1,708 μg/liter, 20 min, 46.6 h, 9.9 liters/h/kg, and 667 liters/kg, respectively, in healthy mice and 1,436 μg/liter, 10 min, 99.3 h, 7.9 liters/h/kg, and 1,122 liters/kg in malaria-infected mice (50-mg single-dose data; noncompartmental analysis). The Cmax, tmax, and t1/2 of DCQ were 614 μg/liter, 4 h, and 32.6 h, respectively, in healthy mice and 345 μg/liter, 2.5 h, and 74.4 h in malaria-infected mice. The metabolic ratio of DCQ to CQ was 1.08 and 0.62 for healthy and malaria-infected mice, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Concentration-time profile of CQ (A) and desethylchloroquine (B) in mice given a single dose of 50-mg/kg i.p. CQ. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5) plasma CQ concentrations in healthy (○) and malaria-infected (●) mice and plasma desethylchloroquine concentrations in healthy (□) and malaria-infected (■) mice. The lines represent the best fit of a two-compartment model to the respective data sets.

Fig. 6.

Concentration-time profile of CQ (A) and desethylchloroquine (B) in mice given five doses of 50-mg/kg i.p. CQ at 24-hour intervals. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5) plasma CQ concentrations in healthy (○) and malaria-infected (●) mice and plasma desethylchloroquine concentrations in healthy (□) and malaria-infected (■) mice. The lines represent the best fit of a two-compartment model to the respective data sets.

Based on the two-compartment model, t1/2α and t1/2β of CQ were 3.3 and 53 h, respectively, in healthy mice and 4.7 and 163 h in malaria-infected mice (Fig. 5). CQ and DCQ data were incomplete (analytes not detected) after 7 days in the multiple-dose study; hence, detailed pharmacokinetic data were not obtained from the two-compartment model. However, combining control and malaria-infected data from the single- and multiple-dose studies, the mean rate of formation of DCQ from CQ (kF) was 0.63 ± 0.55 h−1 and the formation half-life (t1/2,Formation) was 1.7 ± 1.0 h.

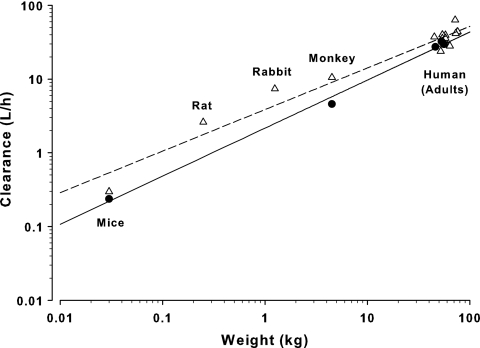

Allometric scaling.

Data for allometric scaling were obtained from 6 animal studies (mice, rats, rabbits, monkeys, and dogs) and 12 human studies (Tables 1 and 2). The allometric plots for CQ plasma clearance in controls and malaria-infected mammals are shown in Fig. 7, and the allometric equations were CL = 3.86 × W0.56 (r2 = 0.96) and CL = 2.16 × W0.65 (r2 = 0.99), respectively. The allometric equations for CQ half-life were t1/2 = 123 × W0.2 (r2 = 0.58) and t1/2 = 134 × W0.11 (r2 = 0.61) for controls and malaria-infected groups, respectively. The allometric equations for CQ volume of distribution were V = 230 × W0.94 (r2 = 0.92) and V = 245 × W0.68 (r2 = 0.9) for controls and malaria-infected groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Chloroquine pharmacokinetic data from healthy mammalian species

| Matrix and species | n | Wt (kg) | Half-life (h) | CLa (liters/h/kg) | Va (liters/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||||

| Mice | 0.03 | 46.6 | 9.9 | 667 | —f | |

| Ratsb | 0.25 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 163 | 55 | |

| Rabbitsc | 5 | 1.25 | 26.7 | 5.9 | 226 | 50 |

| Monkeysc | 6 | 4.5 | 18.8 | 2.34 | 63 | 57 |

| Human, adults | 11 | 75 | 282 | 0.58 | 204 | 27 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 72 | 1,392 | 0.88 | 710 | 22 |

| Human, adults | 7 | 58 | 217 | 0.68 | 181 | 3 |

| Human, adults | 6 | 54 | 250 | 0.74 | 261 | 69 |

| Human, adults | 8 | 58 | 192 | 0.55 | 154 | 69 |

| Human, adults | 10 | 54 | 268 | 0.66 | 132 | 19 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 64 | 386 | 0.44 | 250 | 71 |

| Human, adults | 4 | 76 | 374 | 0.58 | 302 | 71 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 73 | 479 | 0.57 | 283 | 71 |

| Human, adults | 6 | 45 | 67 | 0.83 | 82.6 | 17 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 58 | 70.5 | 0.62 | 63.5 | 17 |

| Human, adults | 30 | 52 | 291 | 0.46 | 129.5 | 32 |

| Total no. of human adultsd | 102 | |||||

| Mean ± SEM | 62 ± 3 | 304 ± 31 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 211 ± 22 | ||

| Whole blood | ||||||

| Micee | 0.025 | 16.5 | 13.1 | 11 | ||

| Rabbits | 8 | 2.0 | 223 | 0.31 | 86 | 2 |

| Dogs, beagle | 7 | 11.8 | 302 | 0.13 | 53 | 1 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 72 | 1,248 | 0.091 | 81 | 22 |

| Human, adults | 7 | 59 | 150 | 0.21 | 45.3 | 47 |

| Human, adults | 17 | 66.5 | 162 | 0.25 | 57.8 | 59 |

CL is apparent clearance (CL/F), and V is apparent volume of distribution (V/F).

Pharmacokinetic parameters determined from concentration-time profile of 48 h after dose.

Pharmacokinetic parameters determined from concentration-time profile of 24 h after dose.

Pharmacokinetic data from 12 human studies comprising 102 volunteers.

Pharmacokinetic parameters determined from concentration-time profile of 4 h after dose.

—, present study.

Table 2.

Chloroquine pharmacokinetic data from mammalian species with malaria infection

| Matrix and species | n | Wt (kg) | Half-life (h) | CLa (liters/h/kg) | Va (liters/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||||

| Mice | 0.03 | 99.3 | 7.9 | 1,122 | —d | |

| Monkeysb | 6 | 4.5 | 30.6 | 1.02 | 44 | 57 |

| Human, adults | 11 | 53 | 302 | 0.61 | 136 | 19 |

| Human, adults | 6 | 46 | 116 | 0.595 | 99.7 | 17 |

| Human, adults | 5 | 56 | 76 | 0.53 | 58.2 | 17 |

| Whole blood | ||||||

| Micec | 0.025 | 5.1 | 16.8 | 11 | ||

| Human, children | 9 | 21 | 0.15 | 112 | 52 | |

| Human, children | 83 | 12 | 115 | 0.24 | 262 | 51 |

| Human, adults | 7 | 54 | 201 | 0.099 | 28.6 | 47 |

| Human, adults | 15 | 46 | 209 | 0.189 | 57.3 | 37 |

CL is apparent clearance (CL/F), and V is apparent volume of distribution (V/F).

Pharmacokinetic parameters determined from concentration-time profile of 24 h after dose.

Pharmacokinetic parameters determined from concentration-time profile of 4 h after dose.

—, present study.

Fig. 7.

Allometric plot for CQ plasma clearance (CL/F) in healthy (▵; CL = 3.86 × W0.56) and malaria-infected (●; CL = 2.16 × W0.65) species (log scale on both axes).

Using allometric scaling principles and the equation for CQ plasma clearance in malaria infection (CL = 2.16 × W0.65), a dose of 35 to 40 mg/kg CQ base would be required in children weighing 10 to 20 kg in order to achieve the same plasma concentrations as the adult dose of 25 mg/kg CQ base (73). By comparison, a simple weight-based equation (dosechild [mg] = doseadult [mg] × [weightchild/weightadult]0.75 [30]) would estimate a similar dose range of 30 to 35 mg/kg for children of 10 to 20 kg in body weight.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides a novel perspective on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of CQ in a murine malaria treatment model, and we report the first detailed allometric scaling of CQ pharmacokinetic parameters. As we have demonstrated that CQ efficacy is dependent on both the total dose and the regimen design, our pharmacodynamic data have direct relevance to clinical researchers testing novel dosage strategies in trials (6, 34, 67) and to drug discovery investigators using CQ as a comparator drug.

The single-dose study (Fig. 1) showed a delay of 6 to 12 h before the decline in parasite density and a nadir parasitemia approximately 2 days (i.e., two erythrocytic cycles in P. berghei) after CQ administration. It is therefore likely that the period of maximum efficacy for CQ in this model is on the order of 24 to 36 h posttreatment. By comparison, DHA produces a prompt decline and parasite nadir 24 h after single doses, and the maximum antimalarial effect appears to occur about 12 h posttreatment (23). These observations suggest that characterizing the pharmacodynamic profile of new chemical entities and comparator antimalarial drugs has the scope to improve the study design and interpretation of data in antimalarial drug development research. Although it may not be feasible to compare novel antimalarial compounds to similar drugs (54, 68, 74), comparisons would be assisted by using a range of comparator drugs (53) with established pharmacodynamic profiles.

Direct extrapolation of dosage strategies from animal studies to clinical trials is problematic; however, our multiple-dose data demonstrate that investigations of treatment options can be informative (Fig. 2). The same total dose (50 mg/kg) was shown to be significantly more effective when given as five 10-mg/kg doses over two erythrocytic cycles, compared to a one-cycle (24-h) or single-dose strategy. For each regimen, the nadir parasitemia occurred approximately 2 days after the final dose of CQ, thus providing evidence of a delayed dose-response relationship.

The multiple-dose pharmacodynamic study also produced an interesting finding that would be relevant to investigations of the immune system and malaria infection (Fig. 4). Consistent with our previous reports of piperaquine in the murine malaria model (43, 44), high-dose CQ led to a curative response. This outcome occurred at very low plasma concentrations several weeks after dosing (the value was unable to be extrapolated from the present study but was likely <1 μg/liter) (Fig. 6). Therefore, we can conclude that resolution of the recrudescent parasitemia was a combination of drug efficacy (to reduce the initial parasite bioburden) and immunological mechanisms. Further investigations of this finding were beyond the scope of the present study.

This multiple-dose, murine malaria treatment model could be applied to investigations that complement recent clinical studies of high-dose antimalarial drugs (6, 67). For example, a total dose of 50 mg/kg CQ as a 5-dose regimen over 3 days was given to children for treatment of falciparum malaria (67). This dose is twice the WHO recommendation (for adults and children) of 25 mg/kg CQ as a 3-dose regimen over 3 days (73). Although it was not specifically tested in the present study, we have shown that the murine model could be used for pharmacodynamic comparisons of standard and high-dose regimens, including variable dose intervals. However, as noted previously, the murine studies provide a conceptual understanding and direct extrapolation to human malaria may require prudent consideration (23, 43).

Extending our study to evaluate the combination of CQ and an artemisinin drug (DHA) provided a valuable comparison to previous studies. In vitro and in vivo efficacy studies have shown paradoxical findings for a range of quinoline and artemisinin combinations (12, 13, 15, 21, 26). CQ is reported to be antagonistic and additive in combination with artemisinins in vitro (12, 21, 26) and additive in the Peters 4-day suppressive test in mice (13). Results from our murine treatment model suggest a weak additive effect of CQ and DHA in vivo (Fig. 3). There are few clinical studies of CQ in combination with artemisinin drugs (48), but reports of CQ-artesunate treatment in West Africa and Vietnam suggest that beneficial outcomes can be achieved (24, 33, 49, 63).

By comparison, we have recently shown an additive effect when DHA and piperaquine were administered concurrently in the murine malaria treatment model (43), a finding that is consistent with the clinical efficacy of this combination (7, 46, 58) but contrasts with in vitro data suggesting mild antagonism (15). As suggested by these reports, the selection of antimalarial partner drugs is complex, requiring consideration of the pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and pharmaceutical properties of each drug, alone and in combination. Our studies indicate that this murine model can be a valuable preclinical tool in antimalarial drug discovery and therapeutic refinement (8, 43).

An essential component of in vivo antimalarial efficacy tests is determining the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug(s). However, pharmacokinetic data for CQ in mice were notably deficient. The only specific murine study of CQ pharmacokinetics was an investigation in healthy and malaria-infected (Plasmodium chabaudi) mice (11). Whole-blood CQ concentration was measured for the pharmacokinetic determinations, but the sampling period was only 4 h postdose, therefore limiting the findings to the distribution phase of the pharmacokinetic profile. Nevertheless, Cambie et al. (11) found that malaria infection (particularly high parasitemia of >20% in mice) increased the half-life and V/F, which suggests a decreased CL/F (Tables 1 and 2). One other investigation of CQ pharmacokinetics in healthy mice has been reported, in the context of grapefruit juice interaction (4). However, the data were incomplete and implausible and could not be compared to the present study.

Reports of CQ pharmacokinetics in other nonhuman species also are limited (Tables 1 and 2), but there is general consistency in the findings of a long half-life, large V/F, and low CL/F for CQ. There is a paucity of animal data in malaria infection, but the available human studies suggest modest changes in pharmacokinetic properties of CQ (Tables 1 and 2).

Against this background, our study was designed to provide detailed pharmacokinetic profiles for CQ and the active metabolite, monodesethylchloroquine (DCQ), following single and multiple doses in healthy and malaria-infected (P. berghei) mice. The pharmacokinetic data were consistent with expectations (Fig. 5 and 6), despite incomplete results from the multiple-dose study. As evident in Table 1, the longer t1/2 and lower CL of CQ in malaria infection, compared to healthy controls, were in accordance with other controlled studies (17, 19, 47, 57). The estimated t1/2 of DCQ in malaria-infected and control mice was shorter than the t1/2 of CQ, suggesting that elimination of DCQ is formation rate dependent (61). Further data to support this conclusion were the metabolic ratios (DCQ to CQ) in malaria-infected (0.6) and control (1.08) mice, both of which were comparable to those of malaria-infected patients (47) and healthy volunteers (ratio, 0.78 to 0.87), respectively (22, 32, 59).

Comparison of the pharmacokinetic data from our study was best represented by allometric scaling, although limitations included the paucity of nonhuman data and the matrix used in the studies. The majority of CQ pharmacokinetic studies have used plasma, and all of the applicable human data were represented separately, as this did not alter the allometric equations (Fig. 7). The allometric scaling indicated that the differences in pharmacokinetic parameters between healthy controls and malaria infection were modest (based on confidence intervals [data not shown]), but the power of these comparisons was limited by the small number of species available for the scaling. Although interspecies scaling is well established in antimicrobial chemotherapy (16, 38, 41, 60), there are few reports of scaling for antimalarial drugs (10, 14). Interspecies comparison of halofantrine using data from uninfected rats and dogs, and malaria-infected humans, suggested a predictive relationship for CL and V (10). Allometric scaling has also been applied to predict human clearance of a novel 4-aminoquinoline from pharmacokinetic data in uninfected mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys (14). Therefore, our analysis of CQ suggests that interspecies scaling data could be applied to phase I studies of new antimalarial drugs, particularly for estimating the dose in first-in-human studies.

Despite the potential value of allometric scaling, clinical limitations of this technique have been identified and cautious interpolation of mammalian data to predict pediatric dosing is warranted (20, 30). Nevertheless, weight-based doses for numerous drugs are higher in children than in adults (30) and recent reports indicate that pediatric doses of antimalarials should be reevaluated (6, 66, 67). In relation to the reports of double-dose CQ (50 mg/kg over 3 days [66, 67]), application of a simple weight-based pediatric equation (30) or our allometric equation to the standard WHO adult dose of 25 mg/kg (73) demonstrates that 35 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg, respectively, would be appropriate. Hence, it could be concluded that 50 mg/kg CQ is only 25 to 40% higher than the scaled equivalent dose.

Our study contributes to the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic knowledge of CQ, but limitations associated with animal studies necessitate prudent conclusions. We have evaluated only a small range of dosage strategies, and the pharmacodynamic outcomes were dose dependent, although some generalizations are credible. Our pharmacokinetic results were limited by the incomplete data in the multiple-dose study, and we did not investigate the possibility of dose-dependent pharmacokinetics for CQ. Further pharmacokinetic studies of CQ could include a detailed evaluation of blood/plasma ratio, as well as the effect of severity of malaria infection on CQ pharmacokinetic properties.

We conclude that the biphasic pharmacokinetic profiles of CQ are similar across mammalian species and that scaling of specific parameters is plausible. CQ was shown to have a delayed dose-response relationship and to have additive efficacy when combined with DHA. In addition to demonstrating the scope of preclinical data that can be generated using a murine malaria treatment model, our study provides pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic information for investigators who use CQ as a comparator in drug discovery research programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an NHMRC New Investigator Grant (141103) and an NHMRC Biomedical (Dora Lush) Postgraduate Research Scholarship (323251) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aderounmu A. F., Fleckenstein L. 1983. Pharmacokinetics of chloroquine diphosphate in the dog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 226:633–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aderounmu A. F., Lindstrom B., Ekman L. 1987. The relationship of the pharmacokinetics of chloroquine to dose in the rabbit. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 39:234–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aderounmu A. F., Salako L. A., Lindstrom B., Walker O., Ekman L. 1986. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of chloroquine after single intravenous and intramuscular administration in healthy Africans. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 22:559–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ali B. H., Al-Qarawi A., Mousa H. M. 2002. Effect of grapefruit juice on plasma chloroquine kinetics in mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29:704–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bailer A. J. 1988. Testing for the equality of area under the curves when using destructive measurement techniques. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 16:303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barnes K. I., et al. 2006. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine pharmacokinetics in malaria: pediatric dosing implications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80:582–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bassat Q., et al. 2009. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine and artemether-lumefantrine for treating uncomplicated malaria in African children: a randomised, non-inferiority trial. PLoS One 4:e7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Batty K. T., Law A. S., Stirling V., Moore B. R. 2007. Pharmacodynamics of doxycycline in a murine malaria model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4477–4479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaute-Lafitte A., Temayer-Caillard V., Gonnet-Gonzalez F., Ramiaramanana L., Chabaud A. G., Landau I. 1994. The chemosensitivity of the rodent malarias—relationships with the biology of merozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 24:981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brocks D. R., Toni J. W. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of halofantrine in the rat: stereoselectivity and interspecies comparisons. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 20:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cambie G., Verdier F., Gaudebout C., Clavier F., Ginsburg H. 1994. The pharmacokinetics of chloroquine in healthy and Plasmodium chabaudi-infected mice: implications for chronotherapy. Parasite 1:219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chawira A. N., Warhurst D. C. 1987. The effect of artemisinin combined with standard antimalarials against chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chawira A. N., Warhurst D. C., Robinson B. L., Peters W. 1987. The effect of combinations of qinghaosu (artemisinin) with standard antimalarial drugs in the suppressive treatment of malaria in mice. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 81:554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis C. B., et al. 2009. Comparative preclinical drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic evaluation of novel 4-aminoquinoline anti-malarials. J. Pharm. Sci. 98:362–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis T. M., et al. 2006. In vitro interactions between piperaquine, dihydroartemisinin, and other conventional and novel antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2883–2885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dinev T. G. 2008. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of five aminoglycoside and aminocyclitol antibiotics using allometric analysis in mammal and bird species. Res. Vet. Sci. 84:107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dua V. K., et al. 2002. Pharmacokinetics of chloroquine in Indian tribal and non-tribal healthy volunteers and patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Curr. Sci. 83:1128–1131 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ducharme J., Farinotti R. 1996. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of chloroquine: focus on recent advancements. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 31:257–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edwards G., et al. 1988. Pharmacokinetics of chloroquine in Thais: plasma and red-cell concentrations following an intravenous infusion to healthy subjects and patients with Plasmodium vivax malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 25:477–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Espie P., Tytgat D., Sargentini-Maier M. L., Poggesi I., Watelet J. B. 2009. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics (PBPK). Drug Metab. Rev. 41:391–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fivelman Q. L., Walden J. C., Smith P. J., Folb P. I., Barnes K. I. 1999. The effect of artesunate combined with standard antimalarials against chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:429–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frisk-Holmberg M., Bergqvist Y., Termond E., Domeij-Nyberg B. 1984. The single dose kinetics of chloroquine and its major metabolite desethylchloroquine in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 26:521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibbons P. L., Batty K. T., Barrett P. H., Davis T. M., Ilett K. F. 2007. Development of a pharmacodynamic model of murine malaria and antimalarial treatment with dihydroartemisinin. Int. J. Parasitol. 37:1569–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gil V. S., et al. 2003. Efficacy of artesunate plus chloroquine for uncomplicated malaria in children in Sao Tome and Principe: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97:703–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ginsburg H. 2005. Should chloroquine be laid to rest? Acta Trop. 96:16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta S., Thapar M. M., Mariga S. T., Wernsdorfer W. H., Bjorkman A. 2002. Plasmodium falciparum: in vitro interactions of artemisinin with amodiaquine, pyronaridine, and chloroquine. Exp. Parasitol. 100:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gustafsson L. L., et al. 1983. Disposition of chloroquine in man after single intravenous and oral doses. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 15:471–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hand C. C., Meshnick S. R. 2011. Is chloroquine making a comeback? J. Infect. Dis. 203:11–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishih A., Suzuki T., Muregi F. W., Matsui K., Terada M. 2006. Chloroquine efficacy in Plasmodium berghei NK65-infected ICR mice, with reference to the influence of initial parasite load and starting day of drug administration on the outcome of treatment. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 37:13–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson T. N. 2008. The problems in scaling adult drug doses to children. Arch. Dis. Child. 93:207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karunajeewa H. A., et al. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of piperaquine and chloroquine in Melanesian children with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:237–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karunajeewa H. A., et al. 2010. Pharmacokinetics of chloroquine and monodesethylchloroquine in pregnancy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1186–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kofoed P. E., et al. 2003. No benefits from combining chloroquine with artesunate for three days for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum in Guinea-Bissau. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97:429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kofoed P. E., et al. 2007. Different doses of amodiaquine and chloroquine for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in children in Guinea-Bissau: implications for future treatment recommendations. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101:231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krishna S., White N. J. 1996. Pharmacokinetics of quinine, chloroquine and amodiaquine: clinical implications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 30:263–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laufer M. K., et al. 2006. Return of chloroquine antimalarial efficacy in Malawi. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:1959–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee S. J., et al. 2008. Chloroquine pharmacokinetics in pregnant and nonpregnant women with vivax malaria. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64:987–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lees P., Shojaee A. F. 2002. Rational dosing of antimicrobial drugs: animals versus humans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:269–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewis S. M., Bain B. J., Bates I. 2006. Practical hematology. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lim P., et al. 2010. Decreased in vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates to artesunate, mefloquine, chloroquine, and quinine in Cambodia from 2001 to 2007. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2135–2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mahmood I. 2007. Application of allometric principles for the prediction of pharmacokinetics in human and veterinary drug development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59:1177–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martin R. E., et al. 2009. Chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Science 325:1680–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moore B. R., et al. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperaquine in a murine malaria model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:306–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moore B. R., Ilett K. F., Page-Sharp M., Jago J. D., Batty K. T. 2009. Investigation of piperaquine pharmacodynamics and parasite viability in a murine malaria model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2707–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mwai L., et al. 2009. Chloroquine resistance before and after its withdrawal in Kenya. Malar. J. 8:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Myint H. Y., Ashley E. A., Day N. P., Nosten F., White N. J. 2007. Efficacy and safety of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101:858–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Na-Bangchang K., Limpaibul L., Thanavibul A., Tan-ariya P., Karbwang J. 1994. The pharmacokinetics of chloroquine in healthy Thai subjects and patients with Plasmodium vivax malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 38:278–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Naing C., Aung K., Win D. K., Wah M. J. 2010. Efficacy and safety of chloroquine for treatment in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium vivax infections in endemic countries. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104:695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nguyen M. H., et al. 2003. Treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in southern Vietnam: can chloroquine or sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine be reintroduced in combination with artesunate? Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1461–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nwafor S. V., Akah P. A., Okoli C. O., Onyirioha A. C., Nworu C. S. 2003. Interaction between chloroquine sulphate and aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae) in rabbits. Acta Pharm. 53:305–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Obua C., et al. 2008. Population pharmacokinetics of chloroquine and sulfadoxine and treatment response in children with malaria: suggestions for an improved dose regimen. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65:493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Okonkwo C. A., et al. 1999. Effect of chlorpheniramine on the pharmacokinetics of and response to chloroquine of Nigerian children with falciparum malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. O'Neill P. M., et al. 2009. Candidate selection and preclinical evaluation of N-tert-butyl isoquine (GSK369796), an affordable and effective 4-aminoquinoline antimalarial for the 21st century. J. Med. Chem. 52:1408–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Opsenica I., et al. 2006. Tetraoxane antimalarials and their reaction with Fe(II). J. Med. Chem. 49:3790–3799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Osifo N. G. 1980. Chloroquine pharmacokinetics in tissues of pyrogen treated rats and implications for chloroquine related pruritus. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 30:419–430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Peters W., Robinson B. L. 1999. Malaria, p. 757–773 In Zak O., Sande M. A. (ed.), Handbook of animal models of infection. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 57. Prasad R. N., Garg S. K., Mahajan R. C., Ganguly N. K. 1985. Chloroquine kinetics in normal and P. knowlesi infected rhesus monkeys. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. Toxicol. 23:302–304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ratcliff A., et al. 2007. Two fixed-dose artemisinin combinations for drug-resistant falciparum and vivax malaria in Papua, Indonesia: an open label randomised comparison. Lancet 369:757–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rengelshausen J., et al. 2004. Pharmacokinetic interaction of chloroquine and methylene blue combination against malaria. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60:709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Riviere J. E., Martin-Jimenez T., Sundlof S. F., Craigmill A. L. 1997. Interspecies allometric analysis of the comparative pharmacokinetics of 44 drugs across veterinary and laboratory animal species. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 20:453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rowland M., Tozer T. N. 2011. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamcs: concepts and applications. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 62. Suckow M. A., Danneman P., Brayton C. 2001. The laboratory mouse. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sutherland C. J., et al. 2003. The addition of artesunate to chloroquine for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Gambian children delays, but does not prevent treatment failure. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69:19–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tett S. E., Cutler D. J. 1987. Apparent dose-dependence of chloroquine pharmacokinetics due to limited assay sensitivity and short sampling times. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 31:729–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Titus E. O. 1989. Recent developments in the understanding of the pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action of chloroquine. Ther. Drug Monit. 11:369–379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ursing J., Kofoed P. E., Rodrigues A., Bergqvist Y., Rombo L. 2009. Chloroquine is grossly overdosed and overused but well tolerated in Guinea-Bissau. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:180–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ursing J., et al. 2011. Similar efficacy and tolerability of double-dose chloroquine and artemether-lumefantrine for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum infection in Guinea-Bissau: a randomized trial. J. Infect. Dis. 203:109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vennerstrom J. L., et al. 2004. Identification of an antimalarial synthetic trioxolane drug development candidate. Nature 430:900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Walker O., Salako L. A., Alvan G., Ericsson O., Sjoqvist F. 1987. The disposition of chloroquine in healthy Nigerians after single intravenous and oral doses. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 23:295–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wellems T. E., Plowe C. V. 2001. Chloroquine-resistant malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 184:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wetsteyn J. C., de Vries P. J., Oosterhuis B., van Boxtel C. J. 1995. The pharmacokinetics of three multiple dose regimens of chloroquine: implications for malaria chemoprophylaxis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 39:696–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. White N. J. 2004. Antimalarial drug resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1084–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. World Health Organization 2010. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yeates C. L., et al. 2008. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 4-pyridones as potential antimalarials. J. Med. Chem. 51:2845–2852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yuan J. 1993. Estimation of variance for AUC in animal studies. J. Pharm. Sci. 82:761–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]