Abstract

Spore germination is the first step to Bacillus anthracis pathogenicity. Previous work has shown that B. anthracis spores use germination (Ger) receptors to recognize amino acids and nucleosides as germinants. Genetic analysis has putatively paired each individual Ger receptor with a specific germinant. However, Ger receptors seem to be able to partially compensate for each other and recognize alternative germinants. Using kinetic analysis of B. anthracis spores germinated with inosine and l-alanine, we previously determined kinetic parameters for this germination process and showed binding synergy between the cogerminants. In this work, we expanded our kinetic analysis to determine kinetic parameters and binding order for every B. anthracis spore germinant pair. Our results show that germinant binding can exhibit positive, neutral, or negative cooperativity. Furthermore, different germinants can bind spores by either a random or an ordered mechanism. Finally, simultaneous triggering of multiple germination pathways shows that germinants can either cooperate or interfere with each other during the spore germination process. We postulate that the complexity of germination responses may allow B. anthracis spores to respond to different environments by activating different germination pathways.

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus anthracis is a spore-forming, aerobic, rod-shaped Gram-positive bacterium that causes anthrax disease. Like the spores of many Bacillus and Clostridium species, B. anthracis spores are metabolically dormant and resistant to environmental stress (11, 19). These resistant properties make spores the perfect delivery vehicles for infections (3). When the environment is suitable, spores germinate and differentiate into vegetative cells, thus allowing bacteria to proliferate (10).

The spore germination process is initiated by metabolites, termed germinants, that are believed to bind, in most cases, to germination (Ger) receptors (13, 17). The Ger receptor genes are organized mostly as tricistronic operons that encode three distinct membrane-associated proteins (9, 17). It is believed that germinant recognition by Ger receptor heterocomplexes is the initial step in a series of biophysical and degradative processes that lead to germination (10). These events result in spores losing their resistance and becoming hydrated (19). Germinated spores then enter an outgrowth phase and eventually return to vegetative life.

Seven independent Ger receptors are encoded by the B. anthracis genome: GerA, GerH, GerK, GerL, GerS, GerY, and GerX (16). Mutational analysis has allowed determining the effect of germinant combinations on each Ger receptor in vitro (6). A germination model for B. anthracis spores suggested that Ger receptors interact to form distinct amino acid- and nucleoside-dependent germination pathways (6). B. anthracis spores seem to require either a nucleoside-amino acid combination or two different amino acids to germinate (8, 21).

A previous study showed that l-alanine alone can trigger B. anthracis spore germination by seemingly binding to the GerL receptor but only at nonphysiologically high concentrations. A second germination pathway required the concurrent detection of l-alanine and l-proline by the GerL and GerK receptors. A third germination pathway seemed to require binding of either l-alanine-l-histidine or l-alanine-aromatic amino acids by the GerS, GerH, and GerL receptors (6).

Three more germination pathways appeared to require a purine nucleoside (inosine) in addition to an amino acid. Treatment of B. anthracis spores with inosine and l-alanine triggered germination using the GerS, the GerH, and either the GerK or the GerL receptor. Meanwhile, spores treated with inosine-l-serine or inosine-l-valine required the GerL, GerH, and GerS receptors for germination. Treatment with inosine-l-methionine or inosine-l-proline required coordinated binding to the GerK, GerH, and GerS receptors for spore germination. Finally, when inosine was supplemented with either l-histidine or aromatic amino acids, B. anthracis spore germination required coordinated binding of the GerH and GerS receptors (6).

Interestingly, a more recent study has shown that the GerH receptor was sufficient for low-level germination in the presence of inosine and diverse amino acids (4). Meanwhile, either the GerK or the GerL receptor was independently sufficient for germination at high l-alanine concentrations. Hence, it seems that individual Ger receptor selectivities broadly overlap. This allows Ger receptors to partially compensate for deleted functions, thus allowing low-level germination even if most Ger receptors are disabled (4).

Although isolated germination pathways in B. anthracis spore germination have been determined, the relative activity of each germination pathway has not been elucidated. B. anthracis spores in a biological milieu are exposed to multiple germinants simultaneously. These complex germination signals can be integrated to differentially trigger distinct germination pathways. To date, interactions between multiple active pathways have not been established. We have previously used kinetic assays and chemical probes to study the mechanism of Bacillus and Clostridium spore germination (1, 2, 5, 7, 14, 15). This approach provides mechanistic information, even when the identities of the germination receptors are unknown (14). Recently, other groups have used kinetic approaches to study the mechanism of germination inhibition in Clostridium difficile spores (20). In the present study, we determined the kinetics of B. anthracis spore germination for individual germination pathways. We also tested for synergy when multiple germination pathways are triggered simultaneously. Our results show that germinant binding can show neutral, positive, or negative cooperativity, depending on the identities of cogerminants. Furthermore, we show that different cogerminant combinations can bind to B. anthracis spores either randomly or in an obligated sequential order. Finally, simultaneous triggering of multiple germination pathways shows that amino acid germination signals can synergize or interfere with each other by differentially triggering spore germination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

HistoDenz and amino acids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO).

Bacterial strains and spore preparation.

The B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 strain was a generous gift from Arturo Casadevall (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY). B. anthracis cells were plated in nutrient agar (20 g of agar per liter) supplemented with 1 g KCl, 0.012 g MgSO4, 0.0164 g Ca(NO3)2, 0.126 g MnCl2, and 0.152 g FeSO4. After overnight incubation, individual colonies were picked and grown in LB broth. Cells were replated into 15 to 20 nutrient agar plates to obtain bacterial lawns. Plates were incubated for 5 days at 37°C. The spores were then collected by flooding the plates with ice-cold deionized water. Spores were harvested by centrifugation on a clinical centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 5 min. The resulting pellet was washed with ice-cold deionized water. After two washes, the spores were resuspended and layered on top of a 20-to-50% HistoDenz gradient and centrifuged at 11,500 rpm for 35 min in a floor centrifuge with the brakes off. The spore pellet was then washed five times with ice-cold water and stored at 4°C.

Analysis of germination.

Spores were heat activated at 70°C for 30 min. Activated spores were washed twice with germination buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl) and resuspended to an optical density at 580 nm (OD580) of 1.0. Auto-germination was monitored for 20 min. Spores that did not auto-germinate were used to conduct the germination assays.

Experiments were carried out in 96-well plates (200 μl/well) using a Labsystems iEMS 96-well plate reader equipped with a filter with a cutoff of 580 nm (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA). Experiments were performed in triplicate on at least two different occasions with no fewer than two different spore preparations. Standard deviations were calculated from at least six independent measurements and were typically below 10%. Spore germination was confirmed in selected samples by microscopic observation of aliquots stained using the Schaeffer-Fulton method. Kinetic readings were carried out every minute for 1 h at 25°C. Spores were germinated with various concentrations of cogerminants (concentration ranges were selected to avoid data clusters in double-reciprocal plots) and are listed accordingly in Fig. 1A to E and Fig. S1 to S5 in the supplemental material.

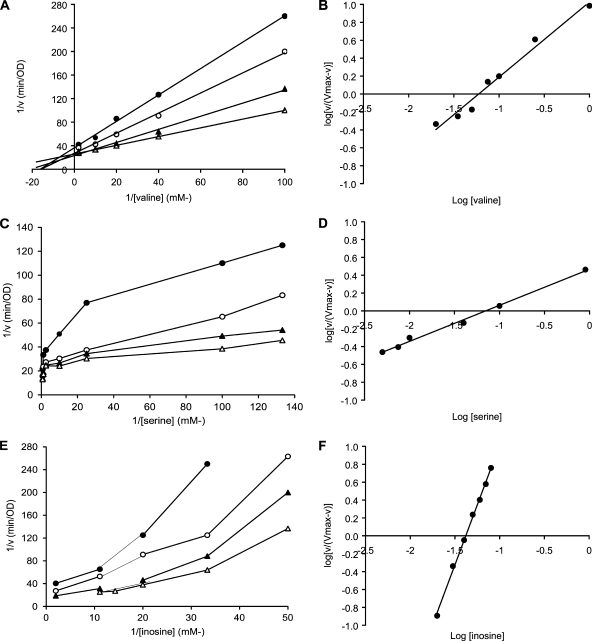

Fig. 1.

Examples of double-reciprocal and Hill plots. Germination rates were calculated from the linear segment of optical density changes over time. (A) Double-reciprocal plots of B. anthracis spore germination at various concentrations of l-valine and 32.5 (●), 50 (○), 75 (▴), and 100 (▵) μM concentrations of inosine; (B) Hill plot for l-valine binding at a saturating inosine concentration; (C) double-reciprocal plots of B. anthracis spore germination at various concentrations of l-serine and 32.5 (●), 75 (○), 125 (▴), and 200 (▵) μM concentrations of inosine; (D) Hill plot for l-serine binding at a saturating inosine concentration; (E) double-reciprocal plots of B. anthracis spore germination at various concentrations of inosine and 10 (●), 20 (○), 60 (▴), and 90 (▵) μM concentrations of l-methionine; (F) Hill plot for inosine binding at a saturating l-methionine concentration.

Data analysis.

Spore germination rates were evaluated based on the decrease in the optical density at 580 nm (OD580). Relative OD580 values were derived by dividing each OD580 reading obtained at different times by the initial OD580. Germination rates (v) were calculated as the slope of the linear portion immediately following the initial lag phase of relative OD values over time. Germination rates were determined for the various combinations of germinants used. The resulting data were plotted as double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[variable germinant]. The various slopes from double-reciprocal plots for one germinant were further plotted against the concentration of the corresponding second germinant to determine the maximum rate of germination (Vmax) and apparent dissociation constants (Km). If necessary, kinetic data were also plotted as double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/the concentration of the variable germinant to the 0.4 power ([variable germinant]0.4) or 1/v versus 1/[variable germinant]2. In these cases, an apparent dissociation constant (K′) was calculated instead of Km. K′ values are composed of Km and interaction factors for cooperativity binding. All plots were fitted using the linear-regression analysis from the SigmaPlot v.9 software.

Germination rates were also obtained for each individual germinant at saturating concentrations (10 Km or 10 K′) of its cogerminant. These data were plotted as Hill plots to obtain Hill numbers (n). All plots were fitted using the linear-regression analysis from the SigmaPlot v.9 software.

Dilution experiments.

B. anthracis spore aliquots were heat activated as described above and resuspended in 1 ml of 100 μM inosine. The spore suspension was then rapidly diluted with a solution of 100 μM l-alanine to a final volume of 25 ml. The dilution causes the concentration of inosine to change from an optimal germinant concentration of 100 μM to an inactive concentration of 4 μM. The diluted spore suspension was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Nongerminated spores and germinated cells were then recovered by filtration through a 0.4-μm filter. The retentate was transferred to a microscope slide and stained using the Schaeffer-Fulton method (12). Three microscopy fields were selected at random to count ungerminated spores (green) and germinated cells (red). A complementary experiment was performed by suspending B. anthracis spores in 1 ml of 100 μM l-alanine and diluting with 100 μM inosine solution to a 25-ml final volume. As a positive germination control, B. anthracis spores were resuspended in 1 ml of a solution containing 100 μM inosine-100 μM l-alanine. As negative controls, B. anthracis spore aliquots were independently resuspended in 1-ml solutions containing either 100 μM inosine-4 μM l-alanine or 4 μM inosine-100 μM l-alanine. Similar experiments were performed for inosine-l-serine, inosine-l-histidine, inosine-l-methionine, and inosine-l-valine cogerminant pairs.

Simultaneous triggering of multiple B. anthracis germination pathways.

B. anthracis spore aliquots were heat activated as described above and individually supplemented with mixtures containing inosine, l-alanine, l-histidine, l-methionine, l-serine, and/or l-valine at 1 mM final concentrations. Fifty-six distinct combinations containing 2 to 6 different cogerminants were tested in triplicate. For all conditions tested, germination rates were determined as described above. Relative germination was obtained by dividing the germination rate of each cogerminant combination by the germination rate of B. anthracis spores treated with all six cogerminants.

RESULTS

In this study, we tested for synergy, cooperativity, and order of binding for binary combinations of amino acids and nucleosides that trigger B. anthracis spore germination. We also tested for interactions between multiple germination pathways. Combinations of inosine-l-valine, inosine-l-serine, inosine-l-methionine, and inosine-l-histidine were able to induce a strong germination response, as previously reported (6). In contrast, combinations of 10 mM inosine-l-proline, inosine-aromatic amino acids, l-alanine-l-proline, or l-alanine-aromatic amino acids showed less than 10% of the maximum germination rate of spores treated with inosine-l-alanine and were not analyzed further.

Kinetic analysis of individual B. anthracis spore germination pathways.

We have previously shown that kinetic analysis can yield mechanistic information for the germination processes of B. anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium sordellii, and C. difficile spores (1, 2, 5, 14, 15). Indeed, double-reciprocal plots for spore germination rate (v) versus germinant concentration can be used to determine the Km (the apparent binding constant of spores for the germinant) and Vmax (the maximum germination rate). Furthermore, double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[germinant] also provide evidence for interactions between germinant binding sites. In this study, we determined kinetic parameters for all known germinant pairs that trigger B. anthracis spore germination (6).

Titration of B. anthracis spores with l-valine at different fixed concentrations of inosine yielded a family of double-reciprocal linear plots that converged at the y axis (Fig. 1A). This suggests that l-valine binding by B. anthracis spores is not cooperative. This is further supported by the Hill plot of l-valine at a saturating inosine concentration, which has a slope of 1 (Fig. 1B). The double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[l-valine] at increasing inosine concentrations converge at the y axis, indicating that the maximum germination rate (Vmax) does not change with increasing inosine concentrations (Fig. 1A). Similarly, each plot intersects the x axis at different positions, indicating that the affinity of spores for l-valine increases with increasing inosine concentrations. Secondary plots allowed determining Km and Vmax values, or 2.9 μM and 2.4 OD/h, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for B. anthracis spore germinationa

| Germinant | Hill n | Km (μM) | Vmax (OD/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| l-Alanineb | 0.9 | 48.6 | 2.8 |

| Inosineb | 1.1 | 270 | 2.4 |

| l-Valine | 0.9 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| Inosine | 1.3 | 47.4 | 4.3 |

| l-Serine | 0.4 | 7.3c | 5.1 |

| Inosine | 1.0 | 30.9 | 2.9 |

| l-Methionine | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Inosine | 2.1 | 1.2c | 2.8 |

| l-Histidine | 0.9 | 2.4 | 3.4 |

| Inosine | 1.2 | 24.3 | 2.6 |

Inosine-l-phenylalanine, inosine-l-proline, l-alanine-l-phenylalanine, l- alanine-l-tyrosine, l-alanine-tryptophan, and l-alanine-l-proline showed no significant germination at 10 mM.

Values are from the work of M. Akoachere et al. (2).

Indicates K′, a constant that contains both the Km of the substrate and the interacting factors that are involved in the cooperativity between the different binding sites.

Titration of B. anthracis spores with inosine at different fixed concentrations of l-valine resulted in linear double-reciprocal plots that also converged on the y axis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Secondary plots allowed determining Km and Vmax values of 47.4 μM and 4.3 OD/h, respectively (Table 1). l-Valine affects the affinity of spores for inosine, which is similar to the effect of inosine binding on l-valine. This suggests that the binding of each germinant alters spores' affinity for the other germinant. Hill plots for both valine and inosine binding suggest that both germinants bind noncooperatively to B. anthracis spores. We have seen similar behavior for the germination of B. anthracis spores with inosine and l-alanine (2).

Titration of B. anthracis spores with l-serine at different fixed concentrations of inosine resulted in a family of double-reciprocal downwardly curved plots rather than the expected linear plots (Fig. 1C). This is characteristic of a system with negative cooperativity (18). The Hill plot for serine binding at saturating concentrations of inosine also showed negative cooperativity, with a Hill number of 0.4 (Fig. 1D). Double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[l-serine]0.4 at increasing inosine concentrations resulted in linear plots. This suggests that the binding of an l-serine molecule reduces the affinity for the binding of another l-serine molecule at a separate site. The plots of 1/v versus 1/[l-serine]0.4 at increasing inosine concentrations converged at the y axis, indicating that inosine does not affect the maximum germination rate but does affect the affinity of spores for l-serine. The complexity of l-serine binding to B. anthracis spores prevented the calculation of the apparent Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) (14, 15). Instead, intercepts of the x axis by the 1/v versus 1/[l-serine]0.4 double-reciprocal plots allowed for calculating the apparent dissociation constants (K′) that contained both Km and the interacting factors for negative-cooperativity binding. The K′ and Vmax values obtained for l-serine-mediated germination were 7.3 μM0.4 and 5.1 OD/h, respectively (Table 1).

Interestingly, titration of B. anthracis spores with inosine at different fixed concentrations of l-serine resulted in linear double-reciprocal plots and a noncooperative Hill plot with a slope of 1 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The Km and Vmax values obtained were 30.9 μM and 2.9 OD/h, respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[inosine] at increasing l-serine concentrations converged at the y axis, indicating that l-serine does not affect the maximum germination rate but that spores' affinity for inosine increases with increasing l-serine concentrations.

Titration of B. anthracis spores with l-methionine at different fixed concentrations of inosine yielded a family of linear double-reciprocal plots that converged in the upper left quadrant of the double-reciprocal plot (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This shows that both the maximum germination rate (Vmax) and the affinity of spores for l-methionine (Km) increases with increasing inosine concentrations. Secondary plots allowed the determination of Km and Vmax values of 2.1 μM and 2.0 OD/h, respectively (Table 1).

In contrast, titration of B. anthracis spores with inosine at different fixed concentrations of l-methionine resulted in a family of upwardly curved double-reciprocal plots rather than the expected linear plots (Fig. 1E). This suggests that in the presence of l-methionine, binding of inosine shows positive cooperativity. Double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[inosine]2 at increasing l-methionine concentrations resulted in linear plots. The Hill plot for inosine binding at saturating concentrations of l-methionine also showed positive cooperativity, with a Hill number of 2.1 (Fig. 1F). This suggests that binding an inosine molecule increases the affinity for binding of another inosine molecule on a separate site. We have seen similar cooperative behavior for inosine binding by B. cereus (1). The plots of 1/v versus 1/[inosine]2 at increasing l-methionine concentrations converged at the y axis, indicating that inosine does not affect the maximum germination rate but that spores' affinity for inosine increases with increasing l-methionine concentrations. Cooperative behavior for inosine binding in the presence of l-methionine prevented the calculation of Km but allowed the calculation of K′ (see above). K′ and Vmax values obtained were 1.2 μM2 and 2.8 OD/h, respectively (Table 1).

Titration of B. anthracis spores with l-histidine at different fixed concentrations of inosine showed linear double-reciprocal plots and a Hill plot with a slope of 1, suggesting that l-histidine binding is not cooperative. The Km and Vmax values obtained were 2.4 μM and 3.4 OD/h, respectively (Table 1). The double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[l-histidine] at increasing inosine concentrations converged at the top left quadrant, suggesting that both the maximum germination rate (Vmax) and the affinity of spores for l-methionine (Km) increases with increasing inosine concentrations (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Similarly, double-reciprocal plots and Hill plots for the titration of B. anthracis spores with inosine at different fixed concentrations of l-histidine showed no cooperativity for inosine binding. The Km and Vmax values obtained were 24.3 μM and 2.6 OD/h, respectively (Table 1). The double-reciprocal plots of 1/v versus 1/[inosine] at increasing l-histidine concentrations converged on the y axis, suggesting that the maximum germination rate (Vmax) does not change but that the affinity of spores for inosine (Km) increases with increasing l-histidine concentrations (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

Dilution experiments.

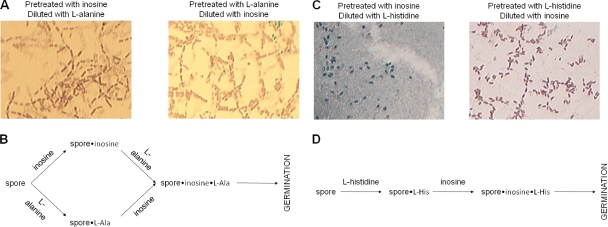

To determine the order of germinant binding to B. anthracis spores, germination was triggered upon fast dilution. B. anthracis spores treated with inosine and rapidly diluted with l-alanine solution germinated normally and were stained red. Germination occurred even though inosine concentration was reduced from an optimal (100 μM) to an inactive (4 μM) concentration. Conversely, l-alanine-treated B. anthracis spores also germinated normally after dilution with an inosine solution (Fig. 2A). As a positive control, B. anthracis spore aliquots were resuspended in a solution containing 100 μM inosine-100 μM l-alanine. In this case, all spores germinated and were stained red (data not shown). As negative controls, B. anthracis spore aliquots were independently resuspended in solutions containing either 100 μM inosine-4 μM l-alanine or 4 μM inosine-100 μM l-alanine. In these cases, spores failed to germinate and were stained green (data not shown). Similar results were observed for dilution experiments of B. anthracis spores using inosine-l-serine and inosine-l-valine.

Fig. 2.

Dilution experiments show different orders of germinant binding for B. anthracis spores. (A) B. anthracis spores were resuspended in 1 ml of 100 μM inosine (or 100 μM l-alanine) prior to rapid dilution to 25 ml with 100 μM l-alanine (or 100 μM inosine). Thirty minutes after inosine exposure, spores were collected by filtration, and pellets were treated with malachite green to stain resting spores and with safranin-O to stain germinated spores. Samples were placed under a microscope, and a field was selected at random. (B) Kinetic scheme showing the putative binding order for B. anthracis spores treated with l-alanine and inosine. (C) B. anthracis spores were resuspended in 1 ml of 100 μM inosine (or 100 μM l-histidine) prior to rapid dilution to 25 ml with 100 μM l-histidine (or 100 μM inosine). Microscopy fields were obtained as described above. (D) Kinetic scheme showing the putative binding order for B. anthracis spores treated with l-histidine and inosine.

Dilution experiments resulted in different germination profiles for B. anthracis spores when inosine and l-histidine were used as cogerminants. B. anthracis spores treated with inosine and diluted with l-histidine solution germinated normally (as described above). In contrast, B. anthracis spores treated with l-histidine and diluted with inosine failed to germinate (Fig. 2C). This germination profile was also observed for dilution experiments of B. anthracis spores using inosine-l-methionine.

Simultaneous triggering of multiple germination pathways.

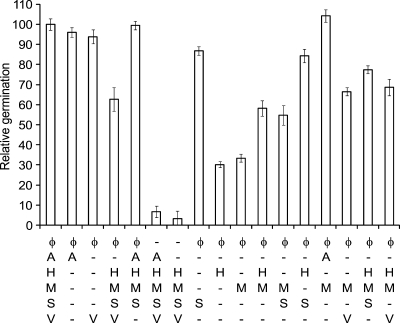

To determine interactions between individual germination pathways, B. anthracis spore aliquots were individually treated with mixtures containing two, three, four, five, or six different germinants. Although all possible cogerminant combinations were tested, most conditions yielded redundant results and will not be discussed further (for example, removal of inosine reduced germination by 90% whether there were 2, 3, 4, or 5 amino acids present in the germination mixture). Inosine-l-alanine and inosine-l-valine mixtures induced B. anthracis spore germination to the same levels as treating spores with all six cogerminants (inosine, l-alanine, l-serine, l-valine, l-histidine, and l-methionine) (Fig. 3). B. anthracis spores treated with a pentanary germinant mixture lacking l-alanine resulted in a 40%-lower germination rate. In contrast, removal of l-valine from the germinant mixture did not reduce the spore germination rate (Fig. 3). Similarly, germinant combinations containing all 5 amino acids but lacking inosine resulted in a 90% decrease in germination rates. Removal of both inosine and l-alanine resulted in no germination (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Simultaneous triggering of multiple germination pathways in B. anthracis spores. B. anthracis spores were treated with mixtures of germinants at 1 mM final concentrations. Relative germination rates were calculated as fractions of germination rates for spores treated with all six germinants. Germination rates were calculated from the linear segment of optical density changes over time. Amino acids are represented by the one-letter code. φ represents inosine.

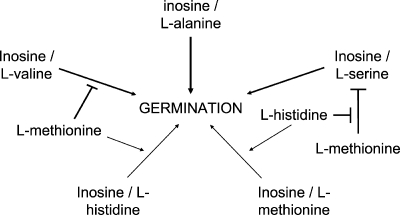

Inosine also triggered germination in binary combinations with l-serine, l-methionine, and l-histidine, albeit at lower rates. Interestingly, even though l-serine shows negative cooperativity, the germination rate for inosine supplemented with l-serine was 80% of the germination rates obtained for spores treated with all six cogerminants. Spores treated with mixtures of inosine-l-methionine and inosine-l-histidine showed reduced germination rates compared with those of spores treated with inosine-l-alanine. However, a ternary mixture of inosine-l-methionine-l-histidine doubled spores' germination rates compared to those of spores treated with either inosine-l-methionine or inosine-l-histidine. Interestingly, addition of l-methionine (but not l-histidine) reduced the germination rate of spores treated with inosine-l-serine and inosine-l-valine but not with inosine-l-alanine. Addition of l-histidine to the inosine-l-methionine-l-serine mixture restored spores' germination rates to values comparable to those of spores germinated with inosine-l-serine mixtures. In contrast, addition of l-histidine did not increase germination rates of spores treated with inosine-l-valine-l-methionine (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model for interactions of B. anthracis germination pathways. Arrows represent positive interactions. Capped lines represent negative interactions. Line thicknesses give relative strengths of the interactions.

DISCUSSION

Mutational analyses have been used to assign the binding of specific germinants to individual B. anthracis germination receptors (6). Furthermore, these results allowed organization of the germination response into distinct pathways formed by interacting germination receptors. More recently, the same group showed that germination receptors can partially substitute for each other in recognizing different cogerminants (4). Due to these complications, it is not possible to correlate germinant binding properties to those of individual receptors. We can, however, determine the effect of specific germinant combinations on wild-type B. anthracis spores. This approach quantitatively measures the spore germination response as an integration of different germination signals and does not require a priori assumptions on germinant binding by specific receptors.

We have previously shown that the germination of B. anthracis spores with inosine and l-alanine resulted in binding synergy between the two cogerminants (2). No cooperative behavior was observed for either l-alanine or inosine binding, in contrast to that for germinant binding by B. cereus, C. sordellii, and C. difficile (1, 14, 15). In this study, we extended our kinetic analysis to include germination pathways triggered by all germinant pairs that have been reported to be sufficient for B. anthracis spore germination. The in vitro kinetic analyses have allowed determining apparent binding affinities of the germinants, maximum rates of germination, and interactions between binding sites.

Kinetic studies of B. anthracis spore germination with specific cogerminants showed variations in their affinities of binding. For each active cogerminant pair, spores' affinity for one germinant increased with the increasing concentration of the corresponding cogerminant. This suggests that different germinant binding sites interact to change their corresponding binding affinities. Furthermore, our results showed that in the absence of inosine, amino acid combinations are not sufficient to optimally trigger B. anthracis spore germination, suggesting that inosine is an essential cogerminant.

Interestingly, inosine binding revealed positive cooperative behavior in the presence of l-methionine, while the same inosine moiety showed no cooperativity when other amino acids were used as cogerminants. Thus, inosine binding is affected by the identity of the cogerminant used. Furthermore, the affinity of spores for inosine varied at least 20-fold depending on the identity of the amino acid cogerminant. These results are consistent with a flexible binding site(s) for inosine that is differentially affected by the binding of amino acids on separate sites. Similarly, amino acid binding in the presence of inosine showed negative or no cooperativity, depending on amino acid structure. Both positive and negative cooperative binding is best explained by the formation of receptor homocomplexes. Similarly, synergy between different cogerminants is best explained by the formation of receptor heterocomplexes. The sum of the kinetic data implies that B. anthracis germination receptors form multiple distinct homo- and heterocomplexes to recognize specific cogerminant combinations.

Dilution experiments allow determining whether cogerminants bind to B. anthracis spores sequentially or randomly. For a random binding mechanism, treatment with optimal concentrations of either germinant will result in the formation of a spore-germinant complex. Upon dilution, the second germinant will bind to the binary complex, thus triggering germination (Fig. 2B). This behavior was seen for B. anthracis spores treated with inosine-l-alanine, inosine-l-serine, and inosine-l-valine. In these cases, complete germination was observed regardless of the order of cogerminant addition.

For an ordered binding mechanism, germination under fast dilution conditions is expected to show a different profile. When spores are sequentially treated with the germinants in the correct order of binding, spores will germinate normally. However, when spores are first treated with the germinant that binds last, no spore activation will occur since the germination machinery will not recognize the germinant. When spores are then diluted, the concentration of this germinant drops to suboptimal levels and spores will not be able to germinate even in the presence of optimal amounts of the germinant that binds first. This behavior was seen for B. anthracis spores treated with inosine-l-histidine and inosine-l-methionine. In these cases, germination was observed only for l-histidine (or l-methionine)-treated spores that were diluted with inosine. Thus, B. anthracis spores must bind l-histidine (or l-methionine) first. The amino acid-spore complex is then competent to bind inosine to complete the germination process (Fig. 2D).

Analysis of the triggering of multiple simultaneous germination pathways showed that inosine-l-alanine is the strongest germination signal. Intriguingly, the binding affinity for inosine in the presence of l-alanine and for l-alanine in the presence of inosine was relatively weak. We postulate that inosine-l-alanine germination results in faster spore commitment to germination than other germinant combinations.

Interestingly, l-methionine and l-histidine synergized to accelerate spore germination. In contrast, l-methionine dampened l-serine- and l-valine-mediated germination pathways but had no effect on l-alanine-induced germination, suggesting complex interplay between the different B. anthracis spore germination pathways (Fig. 4). This was further highlighted by the ability of l-histidine to rescue l-serine (but not l-valine)-mediated germination from l-methionine inhibition. The complexity of germination responses allows specific germination pathways to be triggered under different conditions, depending on the presence or absence of metabolites that act as germination activators and/or inhibitors. Indeed, it was recently shown that different B. anthracis Ger receptors are required for virulence, depending on the infection route (4).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant 1R01AIGM053212 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by NIH grant P20 RR-016464 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 17 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abel-Santos E., Dodatko T. 2007. Differential nucleoside recognition during Bacillus cereus 569 (ATCC 10876) spore germination. New J. Chem. 31:748–755 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akoachere M., et al. 2007. Identification of an in vivo inhibitor of Bacillus anthracis Sterne spore germination. J. Biol. Chem. 282:12112–12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez Z., Abel-Santos E. 2007. Potential use of inhibitors of bacteria spore germination in the prophylactic treatment of anthrax and Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 5:783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carr K. A., Lybarger S. R., Anderson E. C., Janes B. K., Hanna P. C. 2010. The role of Bacillus anthracis germinant receptors in germination and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 75:365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dodatko T., Akoachere M., Jimenez N., Alvarez Z., Abel-Santos E. 2010. Dissecting interactions between nucleosides and germination receptors in Bacillus cereus 569 spores. Microbiology 156:1244–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher N., Hanna P. 2005. Characterization of Bacillus anthracis germinant receptors in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 187:8055–8062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howerton A., Ramirez N., Abel-Santos E. 2011. Mapping interactions between germinants and Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 193:274–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ireland J. A., Hanna P. C. 2002. Amino acid- and purine ribonucleoside-induced germination of Bacillus anthracis DeltaSterne endospores: gerS mediates responses to aromatic ring structures. J. Bacteriol. 184:1296–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCann K. P., Robinson C., Sammons R. L., Smith D. A., Corfe B. M. 1996. Alanine germination receptors of Bacillus subtilis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 23:290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moir A. 2006. How do spores germinate? J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:526–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moir A., Corfe B. M., Behravan J. 2002. Spore germination. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mormak D. A., Casida L. E. 1985. Study of Bacillus subtilis endospores in soil by use of a modified endospore stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1356–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paidhungat M., Setlow P. 2000. Role of Ger proteins in nutrient and nonnutrient triggering of spore germination in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2513–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramirez N., Abel-Santos E. 2010. Requirements for germination of Clostridium sordellii spores in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 192:418–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramirez N., Liggins M., Abel-Santos E. 2010. Kinetic evidence for the presence of putative germination receptors in C. difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 192:4215–4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Read T. D., et al. 2003. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature 423:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross C., Abel-Santos E. 2010. The Ger receptor family in sporulating bacteria. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 12:147–158 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Segel I. H. 1993. Enzyme kinetics. Behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. Wiley Classics Library ed. Wiley Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 19. Setlow P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorg J. A., Sonenshein A. L. 2010. Inhibiting the initiation of Clostridium difficile spore germination using analogs of chenodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid. J. Bacteriol. 192:4983–4990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weiner M. A., Read T. D., Hanna P. C. 2003. Identification and characterization of the gerH operon of Bacillus anthracis endospores: a differential role for purine nucleosides in germination. J. Bacteriol. 185:1462–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.