Abstract

Genotypic characterization of 215 Aeromonas strains (143 clinical, 52 environmental, and 20 reference strains) showed that Aeromonas aquariorum (60 strains, 30.4%) was the most frequently isolated species in clinical and water samples and could be misidentified as Aeromonas hydrophila by phenotypic methods.

TEXT

The genus Aeromonas consists of oxidase-positive, Gram-negative rods that are motile by polar flagella. Aeromonas species are inhabitants of aquatic environments and can also be found in foods, soil, and the microflora of fish (8, 13, 17). In the present study, we analyzed the nucleotide sequences derived from the gyrB and rpoD genes to characterize a collection of 20 reference, 143 clinical, and 52 environmental Aeromonas strains, of which more than 50% comprised A. hydrophila, as previously identified by a conventional biochemical scheme (1, 3). Clinical samples included wound (54 samples), stool (33 samples), blood (33 samples), and 23 miscellaneous specimens. Environmental specimens were collected from water (44 samples), fish (7 samples), and crab (1 sample).

DNA was extracted by the method described by Coenye and LiPuma (4), and amplification and sequencing of the gyrB and rpoD genes were performed as previously described (15, 18). Nucleotide sequences were determined with an ABI 3130XL analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequences of gyrB and rpoD were independently aligned by the CLUSTAL_X program, version 1.8 (16). Genetic distances were obtained using Kimura's (7) two-parameter model, and concatenated trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method (14) with the MEGA program (9).

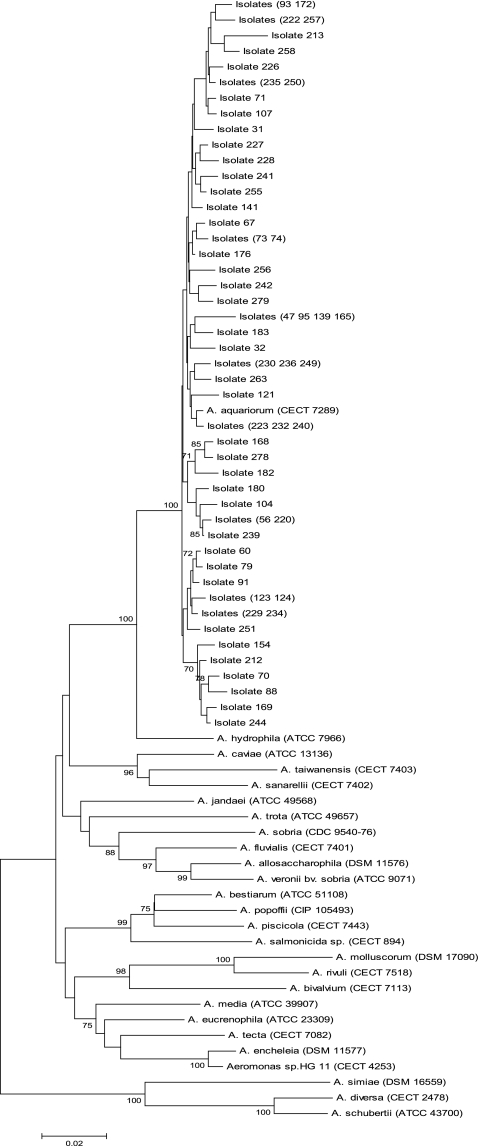

Sequence dissimilarity percentages were calculated using the ClustalW and MEGA5 software. Nucleotide sequencing showed that A. aquariorum was the most frequently isolated aeromonad, with 60 strains (30.7%) clustering with A. aquariorum (CECT 7289) (Fig. 1), followed by A. veronii bv. sobria (49 strains, 25.1%), A. hydrophila (38 strains, 19.4%), and A. caviae (36 strains, 18.4%). In clinical specimens, A. aquariorum was most prevalent in wounds (22 strains, 40.7%) and water samples (24 strains, 54.5%), but it was less frequently isolated from feces (4 strains, 12.1%) and blood (3 strains, 9.0%) samples, while only 2 (28.5%) strains were recovered from fish (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Concatenated neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree showing the position of A. aquariorum strains derived from the rpoD and gyrB sequences.

Table 1.

Distribution of Aeromonas spp. in clinical and environmental specimens

| Species | No. of specimens (% of total) | No. (%) of clinical specimens |

No. (%) of environmental specimens |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound | Stool | Blood | Miscellaneousa | Total | Water | Fish | Crab | Total | ||

| A. allosaccharophila | 1 (0.5) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) | |||||||

| A. aquariorum | 60 (30.7) | 22 (40.7) | 4 (12.1) | 3 (9.0) | 5 (27.1) | 34 (23.8) | 24 (54.5) | 2 (28.5) | 26 (50.0) | |

| A. bestiarum | 1 (0.5) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) | |||||||

| A. caviae | 36 (18.4) | 5 (9.2) | 11 (33.3) | 11 (32.2) | 7 (30.4) | 34 (23.8) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (14.2) | 2 (3.8) | |

| A. hydrophila | 38 (19.4) | 16 (29.6) | 2 (6.0) | 7 (21.2) | 8 (34.7) | 33 (23.0) | 4 (9.0) | 1 (14.2) | 5 (9.6) | |

| A. jandaei | 3 (1.5) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (14.2) | 3 (5.7) | ||||||

| A. media | 3 (1.5) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (14.2) | 1 (1.9) | ||||

| A. salmonicida | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 | 1 (1.9) | |||||

| A. schubertii | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | |||||||

| A. veronii bv. sobria | 49 (25.1) | 9 (16.7) | 14 (42.4) | 10 (30.3) | 3 (13.0) | 36 (25.1) | 12 (27.2) | 1 (14.2) | 13 (25.0) | |

| Aeromonas sp. | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.9) | |||||||

| Total | 195 | 54 | 33 | 33 | 23 | 143 | 44 | 7 | 1 | 52 |

Miscellaneous specimens include A. aquariorum from bone chip (1), urine (2), sputum (1), and unknown (1) specimens, A. caviae from dialysis fluid (1), peritoneal fluid (1), bile (2), T-tube tip (1), and unknown (2) specimens, A. hydrophila from tissue (1), sputum (2), biliary shunt (1), bile (1), pancreatic cyst (1), drain fluid (1), and mortuary (1) specimens, and A. veronii bv. sobria from sputum (2) and appendix (1) specimens.

Biochemically, A. aquariorum could be clearly differentiated from A. hydrophila by its inability to produce acid from l-arabinose, while most strains utilized citrate (93%) or produced alkylsulfatase (73%). In contrast, all A. hydrophila strains tested produced acid from l-arabinose and were less likely to utilize citrate (26%) or produce alkylsulfatase (3%). A. aquariorum differed from A. caviae by a positive Voges-Proskaeur (VP) reaction (95% of A. aquariorum specimens), decarboxylation of lysine (95% positive), and production of gas from glucose (90%), while A. caviae was usually negative in all these tests. A. aquariorum could be differentiated from A. veronii bv. sobria by its ability to utilize dl-lactate (78% versus 2%) and production of staphylolysin (82% versus 0%) (3).

The genus Aeromonas has long been recognized to contain strains that are difficult to differentiate from one another, particularly when identification is based on phenotypic methods alone (1). Housekeeping genes such as rpoD and gyrB perform essential functions in bacteria and, unlike 16S rRNA, are single-copy genes where horizontal transfer seldom occurs (15, 17). The intraspecies dissimilarity derived from the combination of these two genes (approximately 1,294 bp) ranged from 0.4% to 3.5% between the type species and the wild strains identified as A. aquariorum, consistent with the position of these isolates as shown in Fig. 1. The sequence divergence of strain 213 ranged from 0.4% to 4.2%, suggesting that this isolate needs further investigation. Interspecies dissimilarity ranged from 19.1% between A. molluscorum and A. diversa to 1.4% between A. encheleia and Aeromonas sp. HG11, confirming the close relationship that exists between the latter species (see the supplemental material).

Our results revealed that, when used independently, sequences of both genes led to comparable identification, suggesting that gyrB and rpoD were reliable equivalent markers for the taxonomic discrimination of Aeromonas species. Phylogenetic trees generated from the rpoD and gyrB sequences (results not shown) were comparable to that derived from a partial rpoB gene sequence (10) except that the former sequences consistently placed A. molluscorum well within the center of the trees, while it was placed in a more distant position when the tree was constructed from the rpoB sequences alone.

Results obtained in the present study may help to explain the biochemical and genotypic heterogeneity previously observed in A. hydrophila (6, 11). Correct identification occurred in only 35 (33.6%) out of 104 strains phenotypically identified as A. hydrophila, while the remaining strains were reidentified as A. aquariorum (54 strains [51.9%]), A. veronii bv. sobria (14 strains [13.4%]), and A. bestiarum (1 strain [1.2%]) by molecular analysis.

The distribution of A. aquariorum strains in clinical and water samples found in the present study contradicts the long-standing notion that A. caviae, A. hydrophila, and A. veronii bv. sobria represent the most frequently isolated aeromonads (>85% in clinical specimens) (2, 6, 12). The number of A. hydrophila strains reclassified into several different species after genotypic characterization indicates that accurate identification of aeromonads requires molecular methods. Furthermore, our results concurred with those of Soler et al. (15), who suggested that the combined analysis of more than one target improved the resolving power and the ability to differentiate between closely related species.

In summary, accurate identification of Aeromonas to the species level using only biochemical tests is still unreliable and must include a genotypic method. Aeromonas of clinical or environmental interest should be presumptively reported as an Aeromonas species, and the strain should be sent to a reference center for final identification if appropriate molecular facilities are not available locally. Finally, our results are consistent with those of Figueras et al. (5), who suggested that A. aquariorum is globally distributed and can be confused with A. hydrophila.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank/EMBL accession numbers for the rpoD/gyrB gene sequences, respectively, are as follows: A. allosaccharophila DSM 11576, FN773342/FN813470; A. aquariorum CECT 7289, FN773316/FN691767; A. bestiarum ATCC 51108, FN773317/FN065556; A. bivalvium CECT 7113, FN773318/FN691768; A. caviae ATCC 13136, FN773319/FN691769; A. diversa CECT 4254, AY169345/AY101806; A. encheleia DSM 11577, FN773320/FN796740; A. eucrenophila ATCC 23309, FN773321/FN706557; A. fluvialis CECT 7401, FJ603453/FJ603455; A. hydrophila ATCC 7966, FN773322/FN706558; A. jandaei ATCC 49568, FN773323/FN706559; A. media ATCC 33907, FN773324/FN706560; A. molluscorum DSM 7090, FN773325/FN706561; A. piscicola CECT 7443, FM999969/FM999963; A. popoffii CIP 105493, FN773336/FN706562; A. rivuli CECT 7518, FJ969433/FJ969434; A. salmonicida CECT 894, AY169327/AY101773; A. sanarelli CECT 7402, FJ472929/FJ607277; A. schubertii CECT 4240, AY169336/AY101772; A. simiae DSM 16559, DQ41159/FN706563; A. sobria CDC 9540-76, FN773345/FN706564; A. taiwanensis CECT 7403, FJ474928/FJ807272; A. tecta CECT 7082, FN773337/FN796745; A. trota ATCC 49657, FN773339/FN796746; A. veronii bt. sobria ATCC 9071, FN773340/FN796747. Accession numbers for the rpoD gene sequence (wild strains) are A. allosaccharophila, FN773344; A. aquariorum, FR675826 to FR675856, FR675886 to Fr675894, FR681589 to FR681596, FN77333, FN773334, FN796724 to FN796728, FN796733, FN808217, FR682782; A. bestiarum, FN773343; A. caviae, FN796729, FR681906 to FR681925, FR682010 to FR682023; A. hydrophila, FN795730, FR681805 to FR681811, FR681865 to FR681892; A. jandaei, FN773326, FN773327, FR682798; A. media, FN773332, FR682799, FR682800; A. salmonicida, FN773330, FN773331; A. schubertii, FR865967; A. veronii bt. sobria, FR682024, FN773335, FR682572 to FR682581, FR682762 to FR682794, FR682796, FR682797; Aeromonas sp., FN773335. Accession numbers for the gyrB gene sequence (wild strains) are A. allosaccharophila, FN691770; A. aquariorum, FR675858 to FR675872, FR676941 to FR676960, FR681574 to FR681588, FN796734 to FN796739, FN706555, FN796752, FN691766; A. bestiarum, FN691771; A. caviae, FR682025 to FR682044, FR682131 to FR682140, FR682504 to FR682507, FR685963 to FR865964; A. hydrophila, FN796741, FR681597 to FR681606, FR681735 to FR681761; A. jandaei, FR682555, FN796742, FN796743; A. media, FN691772, FR682802, FR682803; A. salmonicida, FR682801, FN796744; A. schubertii, FN691774; A. veronii bt. sobria, FN691773, FN796749, FN796750, FR682508 to FR682554; Aeromonas sp., FN691773.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eileen Pratt for her excellent technical contribution and M. J. Figueras from the Facultat de Cience and Medicina de la Salut, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain, for kindly reviewing the early stages of this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbott S. L., Cheung W. K. W., Janda J. M. 2003. The genus Aeromonas: biochemical characteristics, atypical reactions, and phenotypic identification schemes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2348–2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altwegg M., Geiss H. K. 1989. Aeromonas as a human pathogen. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 16:253–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aravena-Román M., Riley T. V., Inglis T. J. J., Chang B. J. 2011. Phenotypic characteristics of human clinical and environmental Aeromonas in Western Australia. Pathology 43:350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coenye T., LiPuma J. J. 2002. Use of the gyrB gene for the identification of Pandoraea species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Figueras M. J., et al. 2009. Clinical relevance of the recently described species Aeromonas aquariorum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3742–3746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janda J. M., Abbott S. L. 1998. Evolving concepts regarding the genus Aeromonas: an expanding panorama of species, disease presentations, and unanswered questions. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:332–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimura M. A. 1980. Simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirov S. M. 1993. The public health significance of Aeromonas spp. in foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 20:179–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar S., Tamura K., Jakobsen I. B., Nei M. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lamy B., Laurent F., Kodjo A. 2010. Validation of a partial rpoB gene sequence as a tool for phylogenetic identification of aeromonads isolated from environmental sources. Can. J. Microbiol. 56:217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miyata M. T. A., Inglis V., Yoshida T., Endo M. 1995. RAPD analysis of Aeromonas salmonicida and Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 79:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ørmen Ø., Granum P. E., Lassen J., Figueras M. J. 2005. Lack of agreement between biochemical and genetic identification of Aeromonas spp. APMIS 113:203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodriguez-Calleja J. M., Garcia-Lopez M. L., Santos J. A., Otero A. 2006. Rabbit meat as a source of bacterial foodborne pathogens. J. Food Prot. 69:1106–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saitou N., Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soler L., et al. 2004. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Aeromonas based on two housekeeping genes. Int. J. Sys. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1511–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vally H., Whittle A., Cameron S., Dowse G. K., Watson T. 2004. Outbreak of Aeromonas hydrophila wound infections associated with mud football. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1084–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yañez M. A., Catalan V., Apraiz D., Figueras M. J., Martinez-Murcia A. J. 2003. Phylogenetic analysis of members of the genus Aeromonas based on gyrB gene sequences. Int. J. Sys. Evol. Microbiol. 53:875–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.