Abstract

A custom-designed microarray containing 220 virulence genes of Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus [GAS]) was used to test group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (GCS) field strains causing bovine mastitis and group C or group G Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (GCS/GGS) isolates from human infections, with the latter being used for comparative purposes, for the presence of virulence genes. All bovine and all human isolates carried a fraction of the 220 genes (23% and 39%, respectively). The virulence genes encoding streptolysin S, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, the plasminogen-binding M-like protein PAM, and the collagen-like protein SclB were detected in the majority of both bovine and human isolates (94 to 100%). Virulence factors, usually carried by human beta-hemolytic streptococcal pathogens, such as streptokinase, laminin-binding protein, and the C5a peptidase precursor, were detected in all human isolates but not in bovine isolates. Additionally, GAS bacteriophage-associated virulence genes encoding superantigens, DNase, and/or streptodornase were detected in bovine isolates (72%) but not in the human isolates. Determinants located in non-bacteriophage-related mobile elements, such as the gene encoding R28, were detected in all bovine and human isolates. Several virulence genes, including genes of bacteriophage origin, were shown to be expressed by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). Phylogenetic analysis of superantigen gene sequences revealed a high level (>98%) of identity among genes of bovine GCS, of the horse pathogen Streptococcus equi subsp. equi, and of the human pathogen GAS. Our findings indicate that alpha-hemolytic bovine GCS, an important mastitis pathogen and considered to be a nonhuman pathogen, carries important virulence factors responsible for virulence and pathogenesis in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Alpha-hemolytic Lancefield group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (GCS) is a pathogen frequently associated with clinical and subclinical bovine mastitis, a disease that causes major economic losses in the dairy industry (51, 67). Virulence determinants have been identified for this pathogen, such as surface proteins which specifically interact with plasma or extracellular matrix proteins of the host, such as alpha-2-macroglobulin, plasminogen, albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, and collagen (30, 35, 46, 64), and genes coding for proteins assumed to play a role in mastitis, such as the alpha-2-macroglobulin-, immunoglobulin G-, or immunoglobulin A-binding protein Mig (25, 55); the alpha 2-macroglobulin- or immunoglobulin G-binding protein Mag (24); and a fibrinogen-binding M-like protein (65).

Recently, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae was reported to be associated with toxic shock-like syndrome in cattle (9), suppurative polyarthritis in lambs (28), bacteremia in dogs (66), and systemic granulomatous inflammatory disease and severe septicemia in fish (16) and in ascending upper limb cellulitis in humans in contact with raw fish (27). The presence of the streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin G gene (spegg) and streptolysin S structural gene (sagA), which have been associated with invasive disease in the exclusively human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus [GAS]), has been documented for fish isolates of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (1). We have previously reported the presence of GAS phage-carried virulence genes among alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates from bovine mastitis, namely, the streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin genes speK, speC, speL, and speM; the phage DNase I gene spd1; and other genes encoding antimicrobial resistance determinants located on mobile genetic elements (MGEs) (47). So far, no more information is available regarding the presence of GAS virulence genes among S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains, and nothing is known regarding the presence of GAS prophages in S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae. However, the exchange of lysogenic phages among GAS and other human and animal species, particularly group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (a pathogen that colonizes and infects humans with a clinical spectrum of diseases resembling those caused by GAS), Streptococcus equi subsp. equi (exclusively horse pathogen), and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus (a zoonotic pathogen) isolates, was previously reported (19, 68).

The aim of the present work was to use a microarray of genes encoding GAS virulence factors (41) to have a better insight into the virulence gene pool (encoded or not by mobile genetic elements) shared between GAS and alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates associated with bovine mastitis in comparison with beta-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates associated with human disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and identification.

A total of 18 alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae field isolates of Lancefield group C (GCS), one of the causative agents of bovine subclinical mastitis in dairy herds in Portugal, were used in the present study. Detailed information regarding these field isolates, including identification and molecular typing data, was described previously (47). In addition, six nonduplicated beta-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates of Lancefield group G (group G Streptococcus [GGS]) (n = 5) and group C (GCS) (n = 1) collected in Portugal, causing pharyngitis (n = 5) and invasive disease (n = 1) in humans, were included in the study for the purpose of comparison. The identification of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates was based on colony morphology, hemolysis in blood agar plates, and Lancefield grouping using the Streptex kit (Remel Europe Ltd., Dartford, England) and PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene and sequencing (71).

We have included two invasive GCS alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains in the study, which were analyzed for the detection of selected virulence genes by PCR only (see below). One of these strains was associated with toxic shock-like syndrome in cattle (9). The other strain caused ascending upper limb cellulitis in humans in contact with raw fish (27). The latter strain was previously identified (27) by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA and sodA genes and sequencing (GenBank accession numbers EU693902 and EU719068, respectively). We confirmed the identification of the strain associated with the toxic shock-like syndrome in cattle by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA (71) and sodA (1) genes and sequencing. Sequences were analyzed by using the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (17) and compared with sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (Bethesda, MD) by using the BLAST alignment tool (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

PFGE profiles for clonal characterization.

A description of the bovine S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae GCS field strains (n = 18), including typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), was reported previously (47). The typing of the human S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis GGS/GCS isolates (n = 6) by PFGE was carried out in this study as described previously for the bovine pathogen Streptococcus uberis (48). SmaI-digested DNA banding patterns obtained by PFGE were analyzed visually according to previously established criteria (61).

Microarray design and hybridization.

The microarray was described previously (41) and was used with minor modifications. In brief, the array consists of 70-mer oligonucleotides from the conserved regions of all “classical” GAS virulence factors and orthologues of virulence factors found in other bacterial species as well as putative virulence genes present in the M1, M3, and M18 genomes. In total, 220 virulence factor/extracellular protein genes, 10 housekeeping genes (positive controls), and 10 negative controls were randomly spotted in six locations on the chip.

Genomic DNA was extracted by using zirconicum beads in combination with the Qiagen DNeasy kit. Genomic DNA was partially digested with AluI, yielding fragments of between 500 and 1,000 bp, and labeled with biotin. The labeled DNA was purified (PCR purification kit; Qiagen), and the labeling efficiency was verified by gel electrophoresis. Array hybridization was performed at 42°C for 16 h, followed by incubation with streptavidin-Cy5 using a SlideBooster SB800 instrument (Advalytix). Fluorescence signals were obtained with a DNA microarray scanner (G2565CA; Agilent Technologies) at a 633-nm excitation wavelength and quantified by using ImaGene software (BioDiscovery).

Microarray data processing.

The raw data were corrected for background and transformed to a log scale. A two-component normal-mixture model (39) was fitted to the corrected data by a maximum likelihood method adapted from the mclust package (12). A discriminant function was calculated to represent the propensity of a gene for being present or absent. Discriminant values were stored in a signal probability matrix and colored for presentation purposes using the following scheme: black indicates state 0 (not present), green indicates state 1 (present), and yellow indicates an indecisive measurement.

Confirmation of array data by PCR screening.

In order to confirm the results obtained with the GAS array, PCR was carried out on several genes (speH, speC, speA, speL, speK, speI, speM sdn, ssa, smeZ, sla, drs, prtf2, speG, ska, dppA, lbp, scpA, emm, isp, SpyM3_1736, slo, nga, spegg, and sagA). The primer sequences, gene description, and amplification length of each reaction are described in Table 1. Samples without DNA and strains lacking (negative) or carrying (positive) specific genes were used as controls in the PCR.

Table 1.

Genes and PCR primers used for screening of virulence determinants among group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and group C and G Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates

| Gene description (origin) | Primer target | Primer sequence | Product size (bp) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiphagocytic M protein (chromosome) | emm (forward) | TATTCGCTTAGAAAATTAA | Variable | —a |

| emm (reverse) | GCAAGTTCTTCAGCTTGTTT | |||

| Streptolysin S (chromosome) | sagA (forward) | TACTTCAAATATTTTAGCTACT | 487 | 1 |

| sagA (reverse) | GATGATACCCCGATAAGGATAA | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin H precursor (phage) | speH (forward) | AGATTGGATATCACAGG | 416 | 50 |

| speH (reverse) | CTATTCTCTCGTTATTGG | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin F (chromosome) | speF (forward) | TACTTGGATCAAGACG | 782 | 50 |

| speF (reverse) | GTAATTAATGGTGTAGCC | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin B (chromosome) | speB (forward) | TTCTAGGATACTCTACCAGC | 300 | 23 |

| speB (reverse) | ATTTGAGCAGTTGCAGTAGC | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin C precursor (phage) | speC (forward) | GCAGGGTAAATTTTTCAACGACACACA | 407 | This study |

| speC (reverse) | TGTGCCAATTTCGATTCTGCCGC | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin A precursor (phage) | speA (forward) | ATGGAAAACAATAAAAAAGTATTG | 755 | 36 |

| speA (reverse) | TTACTTGGTTGTTAGGTAGACTTC | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin L precursor (phage) | speL (forward) | CTGTTAGGATGGTTTCTGCGGAAGAG | 605 | This study |

| speL (reverse) | AGCACCTTCCTCTTTCTCGCCT | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin K precursor (phage) | speK (forward) | TACAAATGATGTTAGAAATCCAAGGAACATATATGCT | 656 | This study |

| speK (reverse) | CAAAGTGACTTACTTTACTCATATCAATCGTTTC | 31 | ||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin I precursor (phage) | speI (forward) | AATGAAGGTCCGCCATTTTC | 516 | 36 |

| speI (reverse) | TCTCTCTGTCACCATGTCCTG | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin M precursor (phage) | speM (forward) | CCAATATGAAGATAACAAAGAAAATTGGCACCC | 600 | This study |

| speM (reverse) | CAAAGTGACTTACTTTACTCATATCAATCGTTTC | 31 | ||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin J (chromosome) | speJ (forward) | ATCTTTCATGGGTACG | 535 | 50 |

| speJ (reverse) | TTTCATGTTTATTGCC | |||

| Streptodornase (phage) | sdn (forward) | ACCCCATCGGAAGATAAAGC | 489 | 36 |

| sdn (reverse) | AACGTTCAACAGGCGCTTAC | |||

| Streptococcal DNase I (phage) | spd1 (forward) | CCCTTCAGGATTGCTGTCAT | 400 | 15 |

| spd1 (reverse) | ACTGTTGACGCAGCTAGGG | |||

| Streptococcal superantigen SSA (phage) | ssa (forward) | TCCACAGGTCAGCTTTTACAG | 502 | 36 |

| ssa (reverse) | TGATCAAATATTGCTCCAGGTG | |||

| Phospholipase A2 (phage) | sla (forward) | CTCTAATAGCATCGGCTACGC | 440 | 36 |

| sla (reverse) | AATGGAAAATGGCACTGAAAG | |||

| Mitogenic exotoxin Z (chromosome) | smeZ (forward) | CTTCAATATTCATTGCAATAATTTC | 400 | G. S. Chhatwal |

| smeZ (reverse) | TGTAACTGTTGTTTTGTTAGTTGAT | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin G of S. pyogenes (chromosome) | speG (forward) | TGTATCTTTAGGGATTACTGATCAG | 389 | This study |

| speG (reverse) | CTCGACCTAAAAGCTTATCATCCTT | |||

| Pyrogenic exotoxin G of S. dysgalactiae (chromosome) | spegg (forward) | GCTTATGATGTTACTCCACTTGA | 420 | This study |

| spegg (reverse) | ATAACGCGATTCCGAATCATAGA | |||

| Drs protein (chromosome) | drs (forward) | CAGCAGATGAAGCAAGTAATAGC | 760 | 18 |

| drs (reverse) | CTTGTTTGTCAATTTTGCTTTACGACC | |||

| Fibronectin-binding protein F1 (chromosome) | prtf1 (forward) | TATCAAAATCTTCTAAGTGCTGAG | 930 | 59 |

| prtf1 (reverse) | AATGGAACACTAACTTCGGACGGG | |||

| Fibronectin-binding protein F2 (chromosome) | prtf2 (forward) | ATAGGATTGTCCGGAGTATCA | 2,000 | G. S. Chhatwal |

| prtf2 (reverse) | TTATGTTGCTTCTCACCA | |||

| Streptolysin O (chromosome) | slo (forward) | ACGGCAGCTCTTATCATT | 600 | G. S. Chhatwal |

| slo (reverse) | GACCTCAACCGTTGCTTTGT | |||

| C5A peptidase precursor (transposon) | scpA (forward) | CCAAGACTTCAGCCACAAGG | 591 | G. S. Chhatwal |

| scpA (reverse) | CAATTCCAGCCAATAGCAGC | |||

| Streptokinase A precursor (chromosome) | ska (forward) | CGATCAAAGGGATCATACGG | 598 | G. S. Chhatwal |

| ska (reverse) | AGGTTCACAGTAACGACGGC | |||

| NAD-glycohydrolase precursor (chromosome) | nga (forward) | ATAACGGGAATAAATTGGTCCTC | 408 | This study |

| nga (reverse) | CGCTTTCTTTGTAGACTTGTTTT | |||

| Laminin-binding protein (transposon) | lmb (forward) | AACCCCAAACAGCCTACGCAAG | 375 | This study |

| lmb (reverse) | TAAAACGGGATCCGTCCAGGTAT | |||

| Immunogenic secreted protein (chromosome) | isp.1 (forward) | CAACTGAAAAAACCCCAGAGCC | 429 | This study |

| isp.1 (reverse) | GGTTGAAGTCAAAGGCACCATAA | |||

| Surface lipoprotein DppA (chromosome) | dppA (forward) | CCGTTATGGAGTCCACAATGAA | 1,045 | This study |

| dppA (reverse) | ACTAGCTTTGAGTTTAATAGTAATC | |||

| Putative ATP-binding cassette transporter protein (chromosome) | SpyM3_1736 (forward) | GAGAAGTCAAAGAGGTCTTTGTT | 392 | This study |

| SpyM3_1736 (reverse) | GGTGTCATACTCTAGTTTACCTTT |

Sequence data and phylogenetic analysis of bacteriophage-associated virulence superantigen genes.

Sequences of the superantigen-encoding genes speC, speK, speL, and speM of the bovine mastitis isolates under study, with high levels of identity among them, were chosen to generate an alignment of DNA sequences of the alleles of those genes and homologous sequences deposited in the NCBI database, in particular sequences of the speC, speK, speL, and speM genes of S. pyogenes; the seeL and seeM genes of S. equi subsp. equi; the szeL and szeM genes of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus; and the sdm gene of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae.

The alignment (380 bp) was used to construct a phylogenetic tree by using MEGA, version 4, software (60). The p-distance parameter and neighbor-joining method were used. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 replicates. Deduced amino acid sequences from these bovine alleles were compared with similar sequences from the NCBI database by using the BLAST alignment tool (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Sequencing was performed by STAB-Vida (Lisbon, Portugal), using the same primers used for amplification. Nucleotide sequences were analyzed by using the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (17).

emm typing.

Determination of emm gene (coding the M protein) types was performed as described by the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/M-ProteinGene_typing.htm).

Gene expression assays by RT-PCR.

For RNA extraction, all isolates were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, England) supplemented with 1% yeast extract (BD, Franklin Lakes) (THY) at 37°C until the mid-exponential phase was reached (optical density [OD] at 600 nm of 0.5), and the NucleoSpin RNAII kit (Macherey-Nagel, Dueren, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by the addition of 2 U/μl of DNase I (Applied Biosystems/Ambion). RNA quality was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and images were captured by using the Gel Doc XR system and Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad). To confirm that no remaining DNA was present in RNA samples, PCR assays were performed by targeting the housekeeping genes rpsL and rpsB and the genes under study, speM, speK, speL, speC, spd1, sdn, slo scpA, ska, nga, lmb, isp, dppA, emm, and SpyM3_1736, using RNA as a template. Reverse transcriptase (RT) reactions for cDNA synthesis were performed by using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, New Zealand). PCR targeting of those genes under study was carried out again by using cDNA as a template.

Growth curve analysis.

In order to ascertain if growth curves (using the same media and conditions of growth) of six of the bovine mastitis GCS S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates from the present study (chosen according to their genotype) were comparable or not, an automated growth curve analysis system (BioScreen C, Piscataway, NJ) was used as described previously (6). Briefly, these isolates were grown overnight in THY, and the cells were centrifuged in order to collect 109 CFU in the pellet. After being resuspended and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM, pH 7.0), the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, and 1% (vol/vol) of this bacterial suspension was used to inoculate each of the wells of the BioScreen plaque containing growth media. Three different growth media were tested: THY, bovine blood serum (Probiologica), and bovine milk serum freshly prepared in the laboratory as previously described (42). The growth media were prepared at different pHs (6.0, 6.6, and 7.4), and three different incubation temperatures (37°C, 38°C, and 40°C) were tested for each growth medium, which represent different environmental conditions in the bovine udder (e.g., the body temperature of a healthy cow is around 38°C, which may rise to 40°C during a mastitis infection).

Virulence gene profiling of invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae.

Eighteen virulence genes (sagA, sla, sdn, spd1, speI, speC, speA, speB, speK, speF, speM, speH, speL, speJ, ssa, smeZ, spegg, and prtf1) were searched for by PCR (Table 1) in the two invasive GCS strains that were included in the study.

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data have been deposited in the public ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) under accession number E-MEXP-3168.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequence data have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: JF789447, JF789445, HQ724300, HQ724301, HQ724302, HQ724303, HQ724304, HQ724305, HQ696925, JF789444, JF789442, and JF789443.

RESULTS

Identification by 16S rRNA and sodA gene sequence analyses.

The identification of the bovine mastitis S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates was confirmed by using 16S rRNA gene sequencing as described previously (47). The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all human GCS/GGS isolates from the present study showed 99 to 100% identity to 16S rRNA gene sequences of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis deposited in the NCBI database. Taking into account the phenotypic characteristics of the isolates together with the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, we could confirm the six human beta-hemolytic GGS/GCS isolates included in this study as being S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates.

The 16S rRNA and sodA gene sequences of the GCS strain associated with the toxic shock-like syndrome in cattle were deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers JF789447 and JF789445, respectively), whereas the same above-mentioned sequences of the GCS strain isolated from a case of ascending upper limb cellulitis in humans were already available (accession numbers EU693902 and EU719068, respectively), as described previously (27). Both 16S rRNA and sodA gene sequences of these two strains showed 99 to 100% identity with S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae 16S rRNA and sodA gene sequences available for comparison in the NCBI database.

PFGE profiles.

The 18 bovine S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates had 15 PFGE patterns, as shown previously (47). The six S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates had six different PFGE patterns with more than six band differences and were therefore considered unrelated according to established criteria (61).

emm typing.

None of the 18 alpha-hemolytic group C S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae bovine isolates were typed by emm typing, since no amplification for this gene could be obtained. The emm gene types of the six human S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates were as follows: stC839 (GCS isolate; n = 1), stG485, stG480, stG6792, and stG4831 (GGS isolates; n = 5).

Microarray data.

Of the 220 GAS virulence genes on the array (41), 44 genes (20%) were present in all bovine mastitis GCS (S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae) and in all human GGS/GCS (S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis) isolates, whereas 66 genes (30%) were not present in any of the isolates tested. The remaining genes (50%) showed variable distributions among isolates of both origins. Relevant genes present in at least one isolate (bovine or human) and genes present in all the bovine isolates (with the exception of hypothetical proteins) are shown in Table 2. Nine genes (ska, dppA, lmb, scpA, emm, isp, nga, slo, and SpyM3_1736) were present in all the human isolates and absent in the bovine isolates, whereas only one gene (SpyM3_0345), encoding an uncharacterized protein, was detected in all bovine isolates and absent in all human isolates.

Table 2.

Distribution of group A Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors of the array in bovine mastitis group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates and human noninvasive and invasive group C or G Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates b

| Human group A Streptococcus pyogenes virulence class protein (gene) | Distribution (%) (no. of isolates) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Bovine group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (n = 18) | Human group C/G Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (n = 6) | |

| Adhesins | ||

| Antiphagocytic M protein (emm) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Laminin-binding protein (lmb)a | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Collagen-like surface protein (scl)a | 89 (16) | 100 (6) |

| PAM | 94 (17) | 100 (6) |

| Putative adhesion protein (adcA) | 94 (17) | 100 (6) |

| Putative extracellular matrix-binding protein (epf)a | 94 (17) | 100 (6) |

| Putative pullulanase (pulA) | 94 (17) | 83 (5) |

| Collagen-like protein SclB (sclB) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (plr) | 100 (18) | 83 (5) |

| R28a | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative choline binding protein (SpyM3_0025) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative collagen-like protein (Spy1054) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative enolase (eno) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative internalin A precursor (inlA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Fibronectin-binding proteins | ||

| SfbX | 6 (1) | 17 (1) |

| SfbIa | 89 (16) | 100 (6) |

| PrtF15a | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative fibronectin-binding protein-like protein A (SpyM3_0652) | 100 (18) | 67 (4) |

| Proteases | ||

| C5A peptidase precursor (scpA)a | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Putative C3-degrading proteinase (cppA) | 22 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Putative exfoliative toxin (SpyM3_0632) | 94 (17) | 67 (4) |

| Putative serine protease (degP) | 94 (17) | 100 (6) |

| Putative protease (SpyM3_0418) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Toxins | ||

| Streptolysin O (slo) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Putative hemolysin III (hlyIII) | 83 (15) | 100 (6) |

| Putative hemolysin (hlyX) | 94 (17) | 100 (6) |

| Streptolysin S-associated protein (sagA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative DNA entry nuclease (endA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative hemolysin (hlyA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Other virulence factors | ||

| Dipeptide permease complex (dppA) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Immunogenic secreted protein precursor (isp) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Inhibitor of complement-mediated lysis (sic) | 0 (0) | 50 (3) |

| NAD-glycohydrolase (nga) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Pyrogenic exotoxin G precursor (speG) | 0 (0) | 83 (5) |

| Streptokinase A precursor (ska) | 0 (0) | 100 (6) |

| Transposase (Spy2009)a | 22 (4) | 83 (5) |

| Putative hyaluronidase (hyl) | 28 (5) | 100 (6) |

| Putative 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase (lacG) | 39 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Immunogenic secreted protein precursor homologue (isp.2) | 67 (12) | 100 (6) |

| Extracellular hyaluronate lyase (hylA) | 78 (14) | 50 (3) |

| Streptococcal protective antigen (spa) | 78 (14) | 50 (3) |

| Putative penicillin-binding protein 1A (pbp1a) | 83 (15) | 33 (2) |

| Putative glutathione peroxidase (SpyM3_0428) | 89 (16) | 100 (6) |

| Putative GTP-binding protein LepA (lepA) | 89 (16) | 100 (6) |

| Arginine deiminase (arcA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Maltose/maltodextrin-binding protein (malE)a | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| 67-kDa myosin-cross-reactive streptococcal antigen (SpyM3_0332) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative acid phosphatase (lppC) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative amidase (SpyM18_2055)a | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative carbamate kinase (arcC) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative citrate lyase beta subunit (citE)a | 100 (18) | 50 (3) |

| Putative cytoplasmic membrane protein (lemA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative dipeptidase (pepD) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative dipeptidase (SPyM3_1763) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative ferric uptake regulator (spf) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative fructose-1-phosphate kinase (fruK) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative lipoprotein (atmB) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase (SpyM3_0278) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative metal-binding protein of ABC transporter (mtsA) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (cypB) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative protease maturation protein (prsA) | 100 (18) | 50 (3) |

| Putative proton-translocating ATPase subunit b (SPyM3_0495) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative PTS system IIB component (SPyM3_1679) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative sugar transporter sugar-binding lipoprotein | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative two-component sensor histidine kinase (yesM) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative uridine kinase (udk) | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Bacteriophage-encoded recognized virulence factors | ||

| Streptodornase, phage associated (sdn) | 22 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Putative exotoxin L precursor, phage associated (speL) | 22 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Pyrogenic exotoxin C precursor, phage associated (speC) | 33 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Putative DNase, phage associated (spd1) | 33 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Streptococcal pyrogenic K exotoxin, phage associated (speK) | 50 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Putative exotoxin M precursor, phage associated (speM) | 56 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Other bacteriophage-encoded factors | ||

| Putative DNase | 33 (6) | 50 (3) |

| Putative lysin, phage associated | 89 (16) | 100 (6) |

| Hypothetical phage protein | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

| Putative endolysin, phage associated | 100 (18) | 100 (6) |

Genes associated with lateral gene transfer (non-bacteriophage related).

Only genes present in at least one isolate (bovine or human) and genes present in all bovine group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates are listed. Hypothetical proteins are not listed in the table.

If we restricted the comparison to bacteriophage genes on the array, we observed that 65% of the phage-related genes were present in at least one bovine GCS isolate, whereas 35% were detected in at least one human GCS/GGS isolate. None of the 13 bacteriophage-harbored virulence genes speC, speJ, speI, speH, ssa, mf4, slaA, speA3 speK, speL, speM, spd1, and sdn were detected in human GGS/GCS S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates, whereas at least one of the six genes speC, speK, speL, speM, spd1, and sdn was detected in 72% (n = 13) of the bovine mastitis GCS S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates.

Other GAS genes on the array, located in variable and recombinatory loci of the GAS genomes (40, 41), were detected in both human and bovine isolates. These include the Spy2009 gene, encoding a transposase (57), and sic (at the mga chromosomal location); the SpyM18_2055 gene, coding for an amidase (at the spa chromosomal location), malE (at the maltose chromosomal location); prtF15 and sfbI (at the fibronectin-collagen-T-antigen [FCT]-encoding region); citE (at the cit chromosomal location); and epf (at the sagA chromosomal location). Interestingly, the gene coding for the adhesin R28 carried by a putative integrative conjugative element was present in all bovine and human isolates.

Confirmation of array data by PCR screening.

All PCR results confirmed the GAS microarray data (Table 2), except for the speM, speK, and speG genes. The speM and speK genes share high levels of identity among their DNA sequences, which resulted in false-positive results in the array data. In addition, it was not clear how many isolates carried the speG gene by both the array and PCR amplification results. The latter may be due to a lack of homology between the primers used and the speG gene of S. dysgalactiae (named spegg), as variants of this gene may occur (73). By using other primers (designed in this study) targeting the speM and speK genes of S. pyogenes and spegg of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (73), eight bovine isolates that carried speK, one bovine isolate that carried speM, one bovine isolate that carried speK and speM, and five human isolates that carried spegg were found.

Sequence data and phylogenetic analysis of bacteriophage-associated virulence superantigen genes.

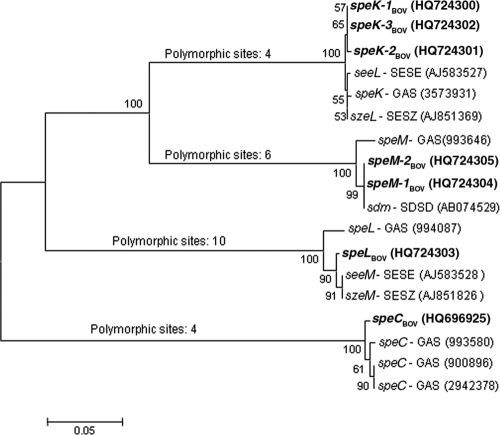

Three speK alleles (speK-1Bov, speK-2Bov, and speK-3Bov) were identified among nine bovine isolates, two speM alleles (speM-1Bov and speM-2Bov) were identified in two bovine isolates, one speC allele (speCBov) was identified in six bovine isolates, and one speL allele (speLBov) was identified in four bovine isolates (GenBank accession numbers HQ724300 to HQ724305 and HQ696925). The phylogenetic tree based on sequences of those alleles and of homologous sequences available in the NCBI database showed four major groups, each one comprising one of the four spe genes (speK, speM, speC, or speL) of bovine S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates and of S. pyogenes, as shown in Fig. 1. The tree also shows that speM and speK diverged more recently, as these two groups showed higher identities among them than with the speL or speC groups.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of superantigen gene sequences of bovine group C Streptococcus from the present study and of sequences of S. pyogenes, S. equi subsp. equi, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus, and S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Bethesda, MD) database. Bovine group C Streptococcus sequences from the present study are designated in the tree in boldface type. Other sequences are designated as follows: SESE, S. equi subsp. equi (seeL and seeM); SESZ, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus (szeL and szeM); SDSD, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (sdm); GAS, S. pyogenes (speK, speM, speL, and speC). GenBank accession numbers (for bovine alleles, seeL, seeM, szeL, szeM, and sdm) and gene ID numbers (for speK, speM, speL, and speC) are included in parentheses after the gene names.

Amino acid sequences deduced from the bovine GCS alleles always showed 98 to 99% identity with the homologous GAS pyrogenic exotoxin gene sequences from the NCBI database, with the exception of bovine SpeL, which showed a higher level of identity with SeeM from S. equi subsp. equi (99%) than with SpeL from S. pyogenes (96%). In particular, and interestingly, SpeM from bovine isolates in the present study showed 99% identity with SpeM from GAS and 100% identity with Sdm from S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (sequences deposited in the NCBI database).

Gene expression assays by RT-PCR.

Transcriptional analysis revealed that the bacteriophage-associated virulence genes speM, speK, speL, speC, spd1, and sdn, detected in bovine GCS isolates, were transcribed and that the virulence genes ska, dppA, lmb, scpA, emm, isp, SpyM3_1736, slo, and nga, detected only in human isolates, were also transcribed.

Growth curve analysis.

In the present study all the strains under analysis by BioScreen reached the highest OD values when grown in bovine blood serum medium (compared to those when grown in THY and bovine milk serum) and under infection-related conditions (at 40°C), with the end of the exponential phase being achieved relatively fast (prior to 5 h of incubation). In bovine milk serum, the end of the exponential phase was achieved in most cases after 10 h of incubation, whereas in THY, growth curves reached the end of the exponential phase prior to 10 h of growth, followed by long stationary phases (no OD decrease was observed during 30 h or more of growth). Interestingly, we have observed differences in growth curves among isolates from the present study, suggesting a strain-specific mode of growth.

Virulence gene profiling of invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae.

Both strains were negative for all the genes tested (n = 18) by PCR, with the exception of the sagA gene. According to the sequences available in the NCBI database, the sagA gene of the animal strain (GenBank accession number JF789442) showed 95% identity either with the sagA gene of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae or with that of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. In parallel, the sagA gene of the human strain (accession number JF789443) was 100% identical to the sagA gene of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and 99% identical to the sagA gene of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis.

DISCUSSION

Assessment of genes associated with MGEs among Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates.

An array containing 220 virulence genes from S. pyogenes (group A Streptococcus [GAS]) was used to analyze the virulence gene pool among S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (group C Streptococcus [GCS]) strains, associated with bovine mastitis, and among S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (group C or group G Streptococcus [GCS/GGS]) isolates, associated with human pharyngitis and invasive disease episodes. We previously reported the presence of GAS virulence genes in bovine GCS isolates (47), which motivated us to further analyze the bovine strains in a search for the presence of other GAS virulence genes (either chromosomal or encoded by mobile genetic elements). The genes included in the array used in this study are from M1, M3, and M18 GAS genomes, of which M1 and M3 in particular are usually associated with severe disease in Europe and North America (33, 53). The results showed that the genes were unevenly distributed among isolates of different host origins. The bovine GCS and human GAS isolates shared 23% of all genes, and both the human GCS/GGS and GAS isolates shared 39% of all genes. A higher content of GAS virulence genes in human GGC/GGS isolates was expected, since both species share the same tissue niche in humans and cause similar spectra of diseases (11, 22, 58). Nevertheless, and most interestingly, none of the 13 bacteriophage virulence-related genes, all associated with GAS disease, were detected in the human GCS/GGS isolates. However, 6 of those 13 genes were detected in the bovine GCS isolates, and we have observed that these GAS phage-related genes (speK, speL, speM, speC, spd1, and sdn) present in bovine GCS are expressed in vitro, suggesting that bacteriophages may also play a role in the genetic plasticity and virulence of bovine mastitis GCS S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates. Specifically, the distribution of genes among the bovine GCS isolates ranged from one phage-related gene (sdn) present in three isolates to five genes (speC-speK-speL-speM-spd1) present in one isolate. Also, the observed linkage of genes in a same bovine GBS strain, in particular speC-spd1 (from the M1 phage), speM-speL (from the M18 phage), and speK (from the M3 phage), indicates polylysogeny, similarly to what was described previously for GAS (2). However, the lack of an association of sets of genes carried by complete phage genomes in our bovine isolates strongly suggests a recombinatory mosaic nature of phages, as observed previously for GAS (2).

Also interesting was the observation that “non-bacteriophage-associated” genes previously shown to be located in recombinatorial and mutational hot spots of the GAS genome and thus considered to be associated with lateral gene transfer (40, 41) were detected in both the bovine GCS and human GCS/GGS isolates from the present study (Table 2). These genes (such as prtf15, epf, citE, and sic) belong to four of the five large chromosomal regions described previously to have variable loci in the GAS genome (41). One of the chromosomal regions includes the FCT locus (63), which is considered one of the major locations of adhesins in GAS isolates. Another chromosomal region is sagA, whereas another region includes the maltose transport and cit operons. The fourth region includes the mga and spa loci.

Furthermore, the gene encoding the cell surface-anchored adhesin R28, carried by putative integrative conjugative elements in GAS which resemble genetic elements of group B Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) (56), was detected in all bovine and human isolates. Also, the C5a peptidase precursor scpA gene as well as the lbp gene, encoding the laminin-binding protein, both known to be carried by a composite transposon of GBS (13), were detected in all human isolates and not in bovine isolates. Together, our data highlight the importance of MGEs mediating lateral gene transfer among different streptococcal species, including bovine GCS isolates.

Nonrandom distribution of GAS virulence genes in bovine mastitis GCS isolates.

Genes of GAS encoding adhesins, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, a putative enolase, PrtF15, R28, a putative internalin A precursor, and putative fibronectin-binding protein-like protein A (4, 10, 26, 56, 69), detected in all bovine GCS S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae isolates, strongly suggest that these might represent important virulence factors in this particular subspecies. In particular, the emm gene, encoding the antiphagocytic M protein, was not present in the bovine isolates, although 94% of these isolates carried the gene encoding PAM, a member of the M protein family.

Also interestingly, streptolysin S, strongly associated with invasive disease caused by GAS and associated with the beta-hemolytic phenotype of GAS and GCS/GGS (S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis) (3, 21), was detected in all bovine isolates, which are alpha-hemolytic (a sequence of this gene from one of the bovine mastitis isolates was deposited in GenBank under accession number JF789444). Furthermore, the presence of the streptolysin S gene (sagA) in alpha-hemolytic strains of group G (S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis) and group C (S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae) streptococci, from human and animal origins, respectively, was reported previously (1, 72).

Bovine GCS is known to grow well in mammary secretions, either during lactation or from dry animals (44, 55), which may be necessary for survival and establishment in the specific environmental niche that is the bovine mammary gland. The results obtained in the present study by using the BioScreen suggest the environmental adaptability of the bovine GCS strains, which demonstrated the ability to grow fast in bovine blood serum and also, although with lower levels of growth, in the remaining tested media (THY and bovine milk serum).

GAS genes related to housekeeping functions were also detected in the bovine isolates from the present study, such as arginine deiminase, a putative metal-binding protein of the ABC transporter, a putative phosphotransferase system (PTS) IIB component, maltose/maltodextrin-binding protein, and putative ferric uptake regulator (7, 29, 32, 49, 52).

The gene encoding 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase, an enzyme of glycoside hydrolase family 1 (5) associated with the capacity for carbohydrate utilization, was detected in only 39% of the bovine isolates (and absent in all human isolates). We have observed differences in growth curves among isolates from the present study, which do not seem to correlate with the presence or absence of the 6-phospho-beta-galactosidase gene. Variable growth patterns of strains in bovine mammary secretions were previously described (44) and may be related to the presence or absence of genes associated with the capacity for carbohydrate utilization but probably not of this particular gene.

Virulence genes detected only in the human GCS/GGS isolates.

In epidemiologically and genetically unrelated S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains from human disease (pharyngitis and invasive), we detected nine genes that were not detected in the bovine isolates. Out of these nine genes, five were previously described for human S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis: lbp (encoding the adhesion Lmb, a laminin-binding protein) (62), ska (encoding the plasminogen-activating Ska-streptokinase A protein) (37), slo (encoding the cytolytic streptolysin O toxin) (54), emm (encoding the M protein), as well as scpA (encoding a C5a peptidase), with the latter two genes acting on the complement pathway of the host, inhibiting bacterial opsonization and phagocytosis (8, 20). Both the lbp and scpA genes have been found in human GBS isolates and are usually absent in bovine GBS isolates (14). These latter two genes and also ska are known to be carried by a bovine pathogen, S. uberis, although Lmb is not required for the attachment of S. uberis to host epithelial cells, and the Ska locus is devoid of plasminogen activator coding sequences (70). The four remaining genes were found for the first time, in our study, in human dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates: the nga gene (encoding a GAS extracellular enzyme NAD-glycohydrolase), associated with cytotoxicity in host cells (34); the isp gene (encoding an immunogenic secreted protein), which has an unknown function, although it is known to be expressed by GAS in the human host and generates antibody responses (38); the dppA gene (encoding a dipeptide permease complex), which is a membrane-associated transporter for dipeptides in GAS and is regulated by the multigene transcriptional regulator Mga (45); and the SpyM3_1736 gene (coding for a putative ABC transporter protein). By gene expression assays (RT-PCR), we observed that all these nine genes from GAS isolates were expressed in human GCS/GGS isolates.

These observations together with the absence of these nine genes in the bovine GCS isolates from this study suggest that they may be more important in human host streptococci than in animal host streptococci.

Sequence data and phylogenetic analysis of superantigen genes of bovine group C S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae.

The bovine alleles were distributed in the four clades according to the S. pyogenes alleles (Fig. 1). In the speK clade, the bovine alleles are organized together and separately from the seeL and szeL genes of S. equi subsp. equi and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus and the speK gene of S. pyogenes, which was expected, since the streptococcal pathogens S. equi subsp. equi, S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus, and S. pyogenes are known to share a phage pool (19). In contrast, within the speL clade, the sequences of the seeM and szeM genes of S. equi subsp. equi and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus, respectively, were organized closer to the bovine speLBov allele from the present study and separately from the speL sequence of S. pyogenes, suggesting a common phage content among the animal species. Also, considering the speC clade, we may speculate that the same or a similar phage(s) is shared between bovine S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae and human S. pyogenes.

The reason why the seeL and szeL sequences were not located in the speL clade and the seeM and szeM sequences were not in the speM clade may be due to incorrect nomenclature given to these genes of S. equi subsp. equi and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Therefore, seeL and szeL should be named seeK and szeK, whereas szeM and seeM should be named seeL and szeL.

The bovine GCS SpeM amino acid sequence (with a length of 177 amino acid residues) showed 100% identity with the S. dysgalactiae-derived mitogen (Sdm) sequence available in the NCBI database. Sdm (encoded by the sdm gene) was the only superantigen with mitogenic activity described so far for S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae (43). In agreement with our findings, the authors of that study (43) also noticed high levels of identity between sdm (from S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae) and speM of S. pyogenes. sdm and speM are probably the same gene, with different nomenclatures.

Our findings underline the role of GAS phages (which are known to be shared with S. equi subsp. equi and S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus) in the genetic diversity of bovine S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains. Additionally, it would be of interest to further search for the presence and expression of virulence factors not represented on the array, which can be either present or not in the genomes of the strains tested. Since several genome sequences of streptococcal species are available, whole-genome and transcriptome comparisons using a pair of S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains described in the present study (the putative zoonotic strain and the bovine mastitis strain with a large pool of GAS virulence phage-related genes) would certainly give further insights into the genomic plasticity of this pathogenic subspecies.

In conclusion, the presence of GAS virulence genes, particularly genes carried by MGEs, either randomly or nonrandomly distributed among strains of bovine GCS may contribute to the increased virulence potential of these strains, namely, the possibility of dissemination to different tissues of the host and to take advantage of new niches. As we have pointed out previously, S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae should not be disregarded as an infectious agent in humans. In fact, this subspecies was associated with invasive disease in humans (27) and here was shown to carry the S. pyogenes streptolysin S gene, further suggesting that S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae is an emerging zoonotic pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by project POCTI/ESP/48407/2002 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal)-FEDER (Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional), PROC 60839 (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Portugal), project reference 46 (Centro de Investigação Interdisciplinar em Sanidade Animal/Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Portugal), and CREM (Centro de Recursos Microbiológicos, Portugal). This work was supported in part by the European Commission (INCO-CT-2006-032390-ASSIST). M.G.R. was supported by Ph.D. grant SFRH/BD/32513/2006 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior). A.N. and R.B. gratefully acknowledge funding through the ASSIST program given by the European Union Commission (contract number 032390).

We gratefully acknowledge Sonia Chénier (Institut National de Santé Animale, Quebec, Canada) and Koh Tse Hsien (Singapore General Hospital, Singapore) for providing the two invasive GCS alpha-hemolytic S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae strains included in this work, David McMillan for his help in the design of the microarray, and Robert Geffers for printing the microarray slides.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdelsalam M., Chen S. C., Yoshida T. 2010. Dissemination of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin G (spegg) with an IS-like element in fish isolates of Streptococcus dysgalactiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 309:105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beres S. B., Musser J. M. 2007. Contribution of exogenous genetic elements to the group A Streptococcus metagenome. PLoS One 2:e800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Betschel S. D., Borgia S. M., Barg N. L., Low D. E., De Azavedo J. C. 1998. Reduced virulence of group A streptococcal Tn916 mutants that do not produce streptolysin S. Infect. Immun. 66:1671–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brassard J., Gottschalk M., Quessy S. 2004. Cloning and purification of the Streptococcus suis serotype 2 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and its involvement as an adhesin. Vet. Microbiol. 102:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cantarel B. L., et al. 2008. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlos A. R., Santos J., Semedo-Lemsaddek T., Barreto-Crespo M. T., Tenreiro R. 2009. Enterococci from artisanal dairy products show high levels of adaptability. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 129:194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casiano-Colón A., Marquis R. E. 1988. Role of the arginine deiminase system in protecting oral bacteria and an enzymatic basis for acid tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1318–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen C. C., Cleary P. P. 1990. Complete nucleotide sequence of the streptococcal C5a peptidase gene of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Biol. Chem. 265:3161–3167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chénier S., Leclère M., Messier S., Fecteau G. 2008. Streptococcus dysgalactiae cellulitis and toxic shock like syndrome in a Brown Swiss cow. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 20:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cork A. J., et al. 2009. Defining the structural basis of human plasminogen binding by streptococcal surface enolase. J. Biol. Chem. 284:17129–17137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies M. R., Shera J., Van Domselaar G. H., Sriprakash K. S., McMillan D. J. 2009. A novel integrative conjugative element mediates genetic transfer from group G Streptococcus to other beta-hemolytic streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 191:2257–2265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fraley C., Raftery A. E. 2006. MCLUST version 3 for R: normal mixture modelling and model-based clustering, technical report no. 504. Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA [Google Scholar]

- 13. Franken C., et al. 2001. Horizontal gene transfer and host specificity of betahaemolytic streptococci: the role of a putative composite transposon containing scpB and lmb. Mol. Microbiol. 41:925–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gleich-Theurer U., et al. 2009. Human serum induces streptococcal c5a peptidase expression. Infect. Immun. 77:3817–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Green N. M., et al. 2005. Genetic diversity among type emm28 group A Streptococcus strains causing invasive infections and pharyngitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4083–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hagiwara H., Takano R., Noguchi M., Narita M. 2009. A study of the lesions induced in Seriola dumerili by intradermal or intraperitoneal injection of Streptococcus dysgalactiae. J. Comp. Pathol. 140:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hall T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartas J., Sriprakash K. S. 1999. Streptococcus pyogenes strains containing emm12 and emm55 possess a novel gene coding for distantly related SIC protein. Microb. Pathog. 26:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holden M. T., et al. 2009. Genomic evidence for the evolution of Streptococcus equi: host restriction, increased virulence, and genetic exchange with human pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 5(3):e1000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hollingshead S. K., Fischettit V. A., Scott J. R. 1986. Complete nucleotide sequence of type 6 M protein of the group A Streptococcus. Repetitive structure and membrane anchor. J. Biol. Chem. 261:1677–1686 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Humar D., et al. 2002. Streptolysin S and necrotising infections produced by group G streptococcus. Lancet 359:124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Igwe E. I., et al. 2003. Identification of superantigen genes speM, ssa, and smeZ in invasive strains of beta-hemolytic group C and G streptococci recovered from humans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jasir A., Tanna A., Efstratiou A., Schalén C. 2001. Unusual occurrence of M type 77, antibiotic-resistant group A streptococci in Southern Sweden. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jonsson H., Frykberg L., Rantamäki L., Guss B. 1994. MAG, a novel plasma protein receptor from Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Gene 143:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jonsson H., Müller H. P. 1994. The type-III Fc receptor from Streptococcus dysgalactiae is also an alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 220:819–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katerov V., Andreev A., Schalén C., Totolian A. A. 1998. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, also binds human fibrinogen: isolation of the protein and mapping of the binding region. Microbiology 144:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koh T. H., et al. 2009. Streptococcal cellulitis following preparation of fresh raw seafood. Zoonoses Public Health 56:206–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lacasta D., Ferrer L. M., Ramos J. J., Loste A., Bueso J. P. 2008. Digestive pathway of infection in Streptococcus dysgalactiae polyarthritis in lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 78:202–205 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lei B., et al. 2003. Identification and characterization of HtsA, a second heme-binding protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 71:5962–5969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leigh J. A., Hodgkinson S. M., Lincoln R. A. 1998. The interaction of Streptococcus dysgalactiae with plasmin and plasminogen. Vet. Microbiol. 61:121–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lintges M., et al. 2007. A new closed-tube multiplex real-time PCR to detect eleven superantigens of Streptococcus pyogenes identifies a strain without superantigen activity. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lortie L. A., Pelletier M., Vadeboncoeur C., Frenette M. 2000. The gene encoding IIAB(Man)L in Streptococcus salivarius is part of a tetracistronic operon encoding a phosphoenolpyruvate:mannose/glucose phosphotransferase system. Microbiology 146:677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luca-Harari B., et al. 2009. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of severe Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1155–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Madden J. C., Ruiz N., Caparon M. 2001. Cytolysin-mediated translocation (CMT): a functional equivalent of type III secretion in Gram-positive bacteria. Cell 104:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mamo W., Fröman G., Sundås A., Wadström T. 1987. Binding of fibronectin, fibrinogen and type II collagen to streptococci isolated from bovine mastitis. Microb. Pathog. 2:417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matsumoto M., et al. 2003. Intrahost sequence variation in the streptococcal inhibitor of complement gene in patients with human pharyngitis. J. Infect. Dis. 187:604–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McArthur J. D., et al. 2008. Allelic variants of streptokinase from Streptococcus pyogenes display functional differences in plasminogen activation. FASEB J. 22:3146–3153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McIver K. S., Subbarao S., Kellner E. M., Heath A. S., Scott J. R. 1996. Identification of isp, a locus encoding an immunogenic secreted protein conserved among group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 64:2548–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McLachlan G. J., Peel D. 2000. Finite mixture models. Wiley series in probability and statistics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 40. McMillan D. J., Sriprakash K. S., Chhatwal G. S. 2007. Genetic variation in group A streptococci. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McMillan D. J., et al. 2007. Variations in the distribution of genes encoding virulence and extracellular proteins in group A streptococcus are largely restricted to 11 genomic loci. Microbes Infect. 9:259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Melchior M. B., et al. 2009. Biofilm formation and genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus bovine mastitis isolates: evidence for lack of penicillin-resistance in Agr-type II strains. Vet. Microbiol. 137:83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miyoshi-Akiyama T., et al. 2003. Streptococcus dysgalactiae-derived mitogen (SDM), a novel bacterial superantigen: characterization of its biological activity and predicted tertiary structure. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1589–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oliver S. P. 1991. Growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species in bovine mammary secretions during the nonlactating and peripartum periods following intramammary infusion of lipopolysaccharide at cessation of milking. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B. 38:538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Podbielski A., Leonard B. A. B. 1998. The group A streptococcal dipeptide permease (Dpp) is involved in the uptake of essential amino acids and affects the expression of cysteine protease. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1323–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rantamäki L. K., Müller H. P. 1995. Phenotypic characterization of Streptococcus dysgalactiae isolates from bovine mastitis by their binding to host derived proteins. Vet. Microbiol. 46:415–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rato M. G., Bexiga R., Nunes S. F., Vilela C. L., Santos-Sanches I. 2010. Human group A streptococci virulence genes in bovine group C streptococci. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rato M. G., et al. 2008. Molecular epidemiology and population structure of bovine Streptococcus uberis. J. Dairy Sci. 91:4542–4551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ricci S., Janulczyk R., Björck L. 2002. The regulator PerR is involved in oxidative stress response and iron homeostasis and is necessary for full virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4968–4976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schmitz F. J., et al. 2003. Toxin-gene profile heterogeneity among endemic invasive European group A streptococcal isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1578–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Seegers H., Fourichon C., Beaudeau F. 2003. Production effects related to mastitis and mastitis economics in dairy cattle herds. Vet. Res. 34:475–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shelburne S. A., et al. 2009. Contribution of AmyA, an extracellular alpha-glucan degrading enzyme, to group A streptococcal host-pathogen interaction. Mol. Microbiol. 74:159–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shulman S. T., et al. 2009. Seven-year surveillance of North American pediatric group A streptococcal pharyngitis isolates. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sierig G., Cywes C., Wessels M. R., Ashbaugh C. D. 2003. Cytotoxic effects of streptolysin O and streptolysin S enhance the virulence of poorly encapsulated group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 71:446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Song X. M., Perez-Casal J., Potter A. A. 2004. The Mig protein of Streptococcus dysgalactiae inhibits bacterial internalization into bovine mammary gland epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stalhammar-Carlemalm M., Areschoug T., Larsson C., Lindahl C. 1999. The R28 protein of Streptococcus pyogenes is related to several group B streptococcal surface proteins, confers protective immunity and promotes binding to human epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 33:208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sumby P., et al. 2005. Evolutionary origin and emergence of a highly successful clone of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus involved multiple horizontal gene transfer events. J. Infect. Dis. 192:771–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takahashi T., Ubukata K., Watanabe H. 6 July 2010, posting date Invasive infection caused by Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis: characteristics of strains and clinical features. J. Infect. Chemother. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0084-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Talay S. R., Valentin-Weigand P., Timmis K. M., Chhatwal G. S. 1994. Domain structure and conserved epitopes of Sfb protein, the fibronectin-binding adhesin of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 13:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tenover F. C., et al. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Terao Y., Kawabata S., Kunitomo E., Nakagawa I., Hamada S. 2002. Novel laminin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, Lbp, is involved in adhesion to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 70:993–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Towers R. J., et al. 2004. Fibronectin-binding protein gene recombination and horizontal transfer between group A and G streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5357–5361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Valentin-Weigand P., Traore M. Y., Blobel H., Chhatwal G. S. 1990. Role of alpha 2-macroglobulin in phagocytosis of group A and C streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 58:321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vasi J., Frykberg L., Carlsson L. E., Lindberg M., Guss B. 2000. M-like proteins of Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Infect. Immun. 68:294–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vela A. I., et al. 2006. Neonatal mortality in puppies due to bacteremia by Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:666–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vieira V. V., et al. 1998. Genetic relationships among the different phenotypes of Streptococcus dysgalactiae strains. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 4:1231–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vojtek I., et al. 2008. Lysogenic transfer of group A streptococcus superantigen gene among streptococci. J. Infect. Dis. 197:225–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Waldemarsson J., Areschoug T., Lindahl G., Johnsson E. 2006. The streptococcal Blr and Slr proteins define a family of surface proteins with leucine-rich repeats: camouflaging by other surface structures. J. Bacteriol. 188:378–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ward P. N., et al. 2009. Evidence for niche adaptation in the genome of the bovine pathogen Streptococcus uberis. BMC Genomics 10:54–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weisburg W. G., Barns S. M., Pelletier D. A., Lane D. J. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Woo P. C., et al. 2003. Analysis of a viridans group strain reveals a case of bacteremia due to Lancefield group G alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in a patient with pyomyositis and reactive arthritis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:613–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao J., et al. 2007. Cloning, expression, and characterization of the superantigen streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin G from Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Infect. Immun. 75:1721–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]