Abstract

A strain of Nocardia was isolated from a pulmonary abscess of a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient in France. Comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis revealed that the isolate represented a strain of Nocardia beijingensis. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was essential to guide the clinicians to successfully treat this infection.

CASE REPORT

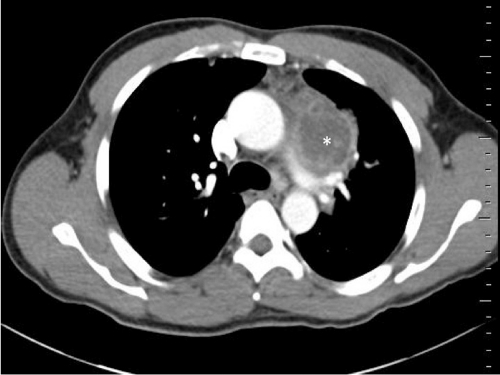

A strain of Nocardia beijingensis was isolated from a 47-year-old male who was admitted to our unit on 23 December 2010 for chest pain and a history of amoxicillin-resistant pneumonia. His main medical history was chronic sinusitis. On examination, he appeared asthenic, without fever. Physical examination concluded there was deteriorated general status, with a weight loss of 5 kg in 8 weeks. Laboratory test results were as follows: hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dl; neutrophils, 13 × 109/liter; lymphocytes, 1.2 × 109/liter; platelets, 357 × 109/liter; and C-reactive protein level, 241 mg/liter (normal range, <6 mg/liter). A chest radiograph disclosed mediastinal widening with a left para-aortic mass. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed an abscess (Fig. 1). Blood cultures were negative.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of the patient's chest showing a left para-aortic mass of ∼7 cm (white asterisk), within the main area, with a necrotic center (mediastinal window).

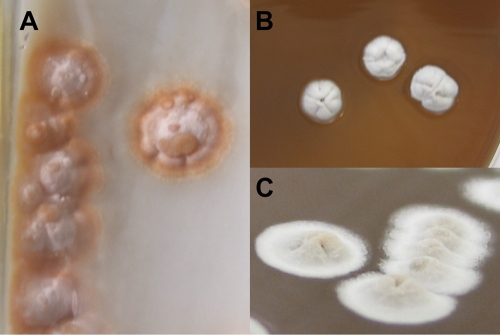

A bronchoalveolar lavage and a lung biopsy of the abscess were performed. In the laboratory, sputum was processed for mycobacterial study: the strain was also isolated from the mycobacterial culture medium. In a modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain, the strain was partially acid fast. The samples were tested for tuberculosis by PCR on the MTB/RIF test platform (GeneXpert; Cepheid) and were negative, except for, interestingly, one of the five probes that target the rpoB gene. Gram-stained smears revealed Gram-positive short filaments, coccoid forms, and branching rods. Primary cultures from the pulmonary abscess and a bronchoalveolar lavage on blood and chocolate agar plates, incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, yielded within 3 days small, chalky white, dome-shaped rough colonies. On Coletsos medium, the colonies appeared irregular and orange colored (Fig. 2). They were Gram-positive rod-shaped organisms producing aerial hyphae. They were partially acid fast and were considered most likely to represent Nocardia spp.

Fig. 2.

Shape and color of colonies on Coletsos (A) and chocolate (B and C) media.

Antibiotic susceptibility among isolates within the genus Nocardia is unpredictable (15); therefore, we assessed susceptibility according to the guidelines of the French Society for Microbiology, using the disk diffusion method or the Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on Mueller-Hinton plates. Although broth microdilution is now recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), two reports suggest that MIC determination by broth microdilution and the Etest give similar results (1, 2), making the Etest suitable and more convenient for routine work. The results were recorded after 48 h (or after 72 h if growth was insufficient after 48 h) and interpreted according to the MIC breakpoints published by the CLSI. However, the Etest method was not available for every antibiotic in our laboratory. Therefore, the agar disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton plates in ambient air was used for the other antibiotics.

In the absence of consensual breakpoints, the interpretation of inhibition zones was made according to the proposed guidelines of the French Society for Microbiology. The profile showed resistance to penicillin (ampicillin MIC90 of >128 μg/ml) and vancomycin (MIC90, >8 μg/ml), susceptibility to imipenem (MIC90, 0.032 μg/ml), aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, tigecycline, linezolid (MIC90, 0.064 μg/ml), quinolones (ciprofloxacin MIC90 of 0.5 μg/ml), cotrimoxazole, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime and ceftriaxone MIC90s of 0.125 and 0.4 μg/ml, respectively), and intermediate susceptibility to meropenem and ertapenem. Prior to the isolation of Nocardia, the patient was empirically treated by ampicillin. Once the diagnosis of nocardiosis was made (based on culture results), and before the availability of drug susceptibility results, the treatment was switched to imipenem and amikacin. Finally, based on the susceptibility results, this treatment was continued for 3 weeks. This resulted in rapid clinical improvement, and intravenous to oral shift therapy was practiced with cotrimoxazole for a total antibiotic course duration of 3 months. A complete resolution of pulmonary symptoms was observed. A cranial CT scan revealed no cerebral abscess. Moreover, regarding the usual association with immunosuppression, HIV serology revealed seropositivity, with an HIV viral load of 47,833 copies/ml and a CD4+ lymphocyte count of 39/mm3: thus, specific treatment was initiated.

The strain was identified to the genus and species levels by 16S rRNA gene-targeted PCR. Briefly, suspensions were made of a single bacterial colony in 20 μl of PCR-grade water, and the suspension was treated using an 800-W microwave oven for 15 s at 480 W, as previously described (14). Cellular debris was pelleted at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant containing the genomic DNA was used in the PCR assay. DNA was amplified with forward (5-AGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3) and reverse (5-GGACTACHAGGGTATCTAAT-3) primers for 35 cycles in a LightCycler 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). Amplification reactions were performed in a volume of 20 μl, which contained 4 μl of DNA template, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.25 μM each primer, and 2 μl of 10× LightCycler FastStart DNA master SYBR green I mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France).

Following an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min and 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing was done at 54°C for 5 s and extension at 72°C for 40 s. The amplicons were then sequenced by a PCR-based reaction using the Big Dye terminator (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) method, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and were detected in an AbiPrism 3500Dx automatic DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The 500-bp amplified DNA sequence was 100% homologous with that of Nocardia beijingensis (GenBank sequence accession no. AB094648; NCBI BLAST and BiBi [http://pbil.univ-lyon1.fr/] phylogenetic tools). Because of the unusual isolation of this strain, confirmation was performed by P. Boiron at the Observatoire Français des Nocardioses, Lyon, France, based on chemotaxonomical characteristics plus sequence analysis of 16S rRNA.

Nocardioses are infections caused by soil-borne aerobic microorganisms belonging to the genus Nocardia. Over 90 species of Nocardia have been described (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/n/nocardia.html), and several are recognized as human and/or animal pathogens, causing diseases ranging from pulmonary or central nervous system infections in immunocompromised patients (∼60% of all reported cases of nocardiosis are associated with underlying immunosuppression) (13) to cutaneous infections in normal hosts (4). In France, on the basis of the numbers of Nocardia strains referred to the National Reference Center for Mycoses and Antifungal Agents, Institut Pasteur, Paris, in the period from 1987 to 1990, it was estimated that between 150 and 250 cases of nocardiosis are diagnosed in France each year (3). The species previously known as Nocardia asteroides complex was the most commonly identified species and accounts for 71.4% of pulmonary infections, 80.0% of central nervous system infections, and 80.0% of systemic infections (14), with the rest being caused by Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia nova. N. asteroides complex has been redistributed among several species, and N. asteroides sensu stricto is now considered an uncommon cause of infections (4, 7).

In HIV-positive patients, Nocardia species are well-known agents of opportunistic infections. The frequency of Nocardia infection in HIV-infected patients has increased during the past few years, and although it is not of great concern as an AIDS-associated infection, its nonspecific clinical presentation in these patients and the slow growth of the bacilli may be confused with other lung infections, such as tuberculosis (11). The mortality rate can be high at 40 to 60% (11, 12), and successful treatment depends on early recognition of the nocardial infection and the initiation of a specific treatment. In 2001, a new species of Nocardia, N. beijingensis, was described by Wang et al., which had been isolated from a soil sample from a sewage ditch at Xishan Mountain in Beijing (17). Strains have been isolated in Asia between 2004 and 2010 from patients with nocardiosis (5, 9, 10, 15, 16), mainly from pulmonary samples (80%) and in immunocompromised patients. To our knowledge, this is the first infectious case reported outside Asia, although some strains have been isolated in Europe, but without strong evidence of their involvement in pathology (6). Besides, our patient never went to these countries.

If morphological and biochemical tests are unable to discriminate the species, it has been proposed that N. beijingensis, N. farcinica, and Nocardia brasiliensis may be differentiated by their drug susceptibility patterns, but certain differentiation relies on molecular methods. N. beijingensis is susceptible to imipenem, tobramycin, and kanamycin, N. brasiliensis is susceptible to tobramycin but resistant to imipenem and kanamycin, and N. farcinica is susceptible to imipenem but resistant to tobramycin and kanamycin (10).

In conclusion, the colony morphology or morphological characteristics of Nocardia do not allow differentiation of the numerous species. The molecular methods based on the 16S rRNA gene for Nocardia identification are crucial. Also, the different species of Nocardia show species-specific drug susceptibility patterns, and patients are most frequently immunosuppressed and generally require antibiotic treatment. Susceptibility testing of all isolates may be imperative as more variability in susceptibilities is being recognized in isolates and new species (8). Therefore, the treatment of choice for Nocardia infections is cotrimoxazole; however, the bacteria are usually also susceptible to imipenem, amikacin, minocycline, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Our patient recovered with prolonged cotrimoxazole treatment after an initial course of imipenem and amikacin. The present report highlights the putative role of N. beijingensis as an agent of pulmonary abscess infection in HIV-positive patients. In addition to the unusual causative species, nocardiosis is a rare primary feature of HIV seropositivity. Finally, reports of isolates from clinical specimens of new species, such as N. beijingensis, underline the need to provide clinical data to establish their relevance in every patient, especially in patients with risk factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Géraldine Appéré and Miche Fabre for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambaye A., et al. 1997. Comparison of agar dilution, broth microdilution, disk diffusion, E-test, and BACTEC radiometric methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of clinical isolates of the Nocardia asteroides complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:847–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biehle J. R., Cavalieri S. J., Saubolle M. A., Getsinger L. J. 1994. Comparative evaluation of the E test for susceptibility testing of Nocardia species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boiron P., Provost F., Chevrier G., Dupont B. 1992. Review of nocardial infections in France 1987 to 1990. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:709–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown-Elliott B. A., Brown J. M., Conville P. S., Wallace R. J., Jr 2006. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:259–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chu R. W., Lung D., Wong S. N. 2008. Pulmonary abscess caused by Nocardia beijingensis: the second report of human infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 27:572–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cloud J. L., et al. 2004. Evaluation of partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for identification of Nocardia species by using the MicroSeq 500 system with an expanded database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Conville P. S., Fischer S. H., Cartwright C. P., Witebsky F. G. 2000. Identification of Nocardia species by restriction endonuclease analysis of an amplified portion of the 16S rRNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:158–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hagerman A., Rodriguez-Nava V., Boiron P., Crisinel P. A., Posfay-Barbe K. M. 2011. Imipenem-resistant Nocardia cyriacigeorgica infection in a child with chronic granulomatous disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1185–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kageyama A., Mikami Y. 2007. Taxonomy and phylogenetic analysis of infectious Nocardia strains isolated from clinical samples. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 48:73–78 (In Japanese.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kageyama A., Poonwan N., Yazawa K., Mikami Y., Nishimura K. 2004. Nocardia beijingensis, is a pathogenic bacterium to humans: the first infectious cases in Thailand and Japan. Mycopathologia 157:155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marquez-Diaz F., Soto-Ramirez L. E., Sifuentes-Osornio J. 1998. Nocardiasis in patients with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs 12:825–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martinez Tomas R., et al. 2007. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors and outcomes. Respirology 12:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Minero M. V., et al. 2009. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine 88:250–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moiton M. P., et al. 2006. Clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic aspects of Nocardia sp. infections in the Bordeaux hospital from 1993 to 2003. Med. Mal. Infect. 36:264–269(In French.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takayanagi K., et al. 2008. A case of pulmonary nocardiosis with Nocardia beijingensis. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 82:43–46 (In Japanese.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tan C.-K., et al. 2010. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of nocardiosis including those caused by emerging Nocardia species in Taiwan, 1998-2008. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang L., et al. 2001. Nocardia beijingensis sp. nov., a novel isolate from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1783–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]