Abstract

Adenovirus E1B-55K represses p53-mediated transcription. However, the phenotypic consequence of p53 inhibition by E1B-55K for cell cycle regulation and drug sensitivity in tumor cells has not been examined. In HCT116 cells with constitutive E1B-55K expression, the activation of p53 target genes such as the p21, Mdm2, and Puma genes was attenuated, despite markedly elevated p53 protein levels. HCT116 cells with E1B-55K expression displayed a cell cycle profile similar to that of the isogenic HCT116p53−/− cells, including unhindered S-phase entry despite DNA damage. Surprisingly, E1B-55K-expressing cells were more sensitive to drug treatment than parental cells. Compared to HCT116 cells, HCT116p53−/− cells were more susceptible to both doxorubicin and etoposide, and E1B-55K expression had no effects on drug treatment. E1B-55K expression increased the rate of cell proliferation in HCT116 but not in HCT116p53−/− cells. Thus, deregulation of p53-mediated cell cycle control by E1B-55K probably underlies sensitization of HCT116 cells to anticancer drugs. Consistently, E1B-55K expression in A549, A172, and HepG2 cells, all containing wild-type (wt) p53, also enhanced etoposide-induced cytotoxicity, whereas in p53-null H1299 cells, E1B-55K had no effects. We generated several E1B-55K mutants with mutations at positions occupied by the conserved Phe/Trp/His residues. Most of these mutants showed no or reduced binding to p53, although some of them could still stabilize p53, suggesting that binding might not be essential for E1B-55K-induced p53 stabilization. Despite heightened p53 protein levels in cells expressing certain E1B-55K mutants, p53 activity was largely suppressed. Furthermore, most of these E1B-55K mutants could sensitize HCT116 cells to etoposide and doxorubicin. These results indicate that E1B-55K might have utility for enhancing chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Adenovirus (Ad) E1B-55K protein physically interacts with the tumor suppressor p53 in transformed as well as infected cells (1, 5, 33). E1B-55K forms a stable complex with DNA-bound p53 and increases p53's binding affinity to its cognate DNA-binding site in vitro (30). Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that E1B-55K also associates with the promoters of endogenous p53 target genes such as the p21 gene (57). Association of E1B-55K with p53 represses p53-mediated transcription in vitro and in cells (31, 52, 57). It has been suggested that a cellular corepressor is required for E1B-55K to inhibit p53-activated transcription (31). The Sin3A corepressor interacts directly with adenovirus type 12 (Ad12) E1B-55K, although this interaction might not be involved in the repression of at least certain p53 target genes (57). Inhibition of p53-mediated transcription by E1B-55K is critical for Ad-mediated transformation of rodent cells that are not permissive for infection by human Ads (50). In Ad-infected cells, E1B-55K forms a complex with the E4orf6 34-kDa protein (E4orf6-34K). The Ad5 E1B-55K-E4orf6 complex recruits a functional E3 ubiquitin ligase complex consisting of Cullin-5 (Cul5), Elongins B and C, and the RING-H2 finger protein Rbx1 (also known as ROC1), resulting in polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p53 (19, 32).

As a sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factor, p53 activates genes involved in cell cycle arrest, senescence, autophagy, and apoptosis (45, 46). Somatic mutations of the p53 gene occur frequently in diverse types of human cancer (37). A vast majority of cancer-derived mutations are missense mutations within the DNA-binding domain of p53 that often disable p53's DNA-binding property. Thus, p53 is inactivated due to mutation in cancers. Likewise, p53 knockout mice develop various tumors at younger ages and with higher frequency than their counterparts carrying wild-type (wt) p53 (10). These and other lines of evidence clearly show that p53 is a critical suppressor of tumorigenesis.

It has become increasingly clear that p53 can promote DNA repair and cell survival in response to mild cellular stresses (23, 47). The prosurvival function of p53 presents a predicament for anticancer therapy. For example, p53-mediated cell cycle arrest in response to genotoxic stress seems to reduce the therapeutic efficacy of several widely used anticancer drugs, such as doxorubicin, a member of the anthracycline group of chemotherapeutics (7). Similarly, tumor xenografts derived from breast cancer cells with wt p53 are more resistant to treatment with epirubicin, another anthracycline, in combination with cyclophosphamide, a DNA-alkylating agent, than those derived from breast cancer cells with mutated p53 (44). Strong expression of the p21 gene and a senescence-like phenotype were observed only in tumors with wt p53, suggesting that p53-induced cell cycle arrest prolongs cell survival during the treatment regimen using epirubicin-cyclophosphamide (44). Clinical data also indicate that breast tumors with mutated p53 correlate with complete treatment responses, whereas those with wt p53 exhibit only a partial treatment response to an epirubicin-cyclophosphamide therapy regimen (2). These observations suggest that inhibition of p53 has the potential to sensitize certain tumor cells to chemotherapy. Consistent with this notion, inhibition of p53 with Pifithrin-alpha (PFTα), a small-molecule inhibitor of p53 (24), sensitized the glioblastoma cell line U87MG, which contains wt p53, to the DNA-alkylating agents temozolomide (TMZ) and 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) (48).

Since E1B-55K is a potent inhibitor of p53, we reason that E1B-55K expression in tumor cells with wt p53 should also potentiate cytotoxicity induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Here we present evidence that E1B-55K-mediated suppression of p53 deregulates cell cycle progression and sensitizes diverse types of tumor cells with wt p53 to the genotoxic agents doxorubicin and etoposide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and DNA constructs.

Human fetal lung fibroblast cell line IMR-90, non-small-cell lung cancer lines A549 and H1299, glioblastoma line A172, and hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Colon cancer line HCT116 and its isogenic counterpart HCT116p53−/− were provided by B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). All cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 units/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 10% fetal calf serum. The GFP-E1B-55K construct was made by inserting the coding region of the Ad12 E1B-55K at the 3′ end of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-coding sequence in the pEGFP-C2 vector. Site-specific E1B-55K mutants were generated using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). All DNA constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Ad12 E1B-55K cDNA and its derivatives are stable in Escherichia coli and thus can be easily manipulated, in contrast to the more extensively studied Ad5 counterpart, which seems less stable genetically in E. coli as we reported previously (27). Consequently, we have studied Ad12 E1B-55K exclusively throughout this study.

Lentiviral vector constructions for expressing various E1B-55K constructs.

All Ad12 E1B-55K constructs were placed under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter in a lentiviral vector. The resulting vectors were cotransfected along with pCMV-VSV-G and pCMVδR8.2 plasmids into 293T cells using the calcium phosphate precipitation method. Eight hours after transfection, transfection mixtures were replaced with fresh medium. Viral supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection and used for transducing various cell lines, as described previously (57). To generate stable cell lines, cells transduced with a lentiviral vector were grown in complete DMEM containing puromycin (2 μg/ml). The resulting puromycin-resistant cells were expanded and used for drug sensitivity experiments and Western blotting.

Western blotting.

Cultured cells were trypsinized, pelleted at 3,500 rpm with a microcentrifuge, and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellets were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with a 100-fold-diluted protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates were frozen at −80°C and thawed at room temperature. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation with a microcentrifuge at the maximal speed (13,500 rpm) at 4°C for 15 min. The protein concentration of the lysates was determined using the Bradford method with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. A total of 30 μg of cellular proteins was loaded in each lane of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Antibodies used for Western blotting detection included anti-Ad12 E1B-55K (custom-made rabbit antiserum [27]), anti-p53 (DO1 and FL393; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Mdm2 (N-20 [Santa Cruz Biotechnology] and 4B11 [provided by Jiandong Chen, Moffitt Cancer Center]), anti-p21 (SXM30; BD Biosciences), anti-Puma (H-136; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GFP (MMS-118P; Covance), anti-Erk1/2 (M5670; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Hsp60 (H99020; BD Biosciences), and anti-PCNA (EPR3821; Epitomics).

Cell cycle analysis.

The HCT116 cell line, the isogenic cell line without p53 (HCT116p53−/−), or their derivatives with expression of Ad12 E1B-55K were seeded in 12-well plates. At 24 h after seeding, cells were left untreated or exposed to 0.1 μM doxorubicin. Cells were trypsinized at 24 h after drug treatment, washed with PBS, and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C. The cells were washed with PBS and then resuspended in cold 70% ethanol (−20°C). The cell suspension was kept at 4°C overnight, the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS containing RNase A (0.56 mg/ml, final concentration), and the cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Propidium iodide (PI) was then added to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min in the dark, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSort instrument (BD Biosciences).

Drug treatment.

Cells (5,000 cells/well) were seeded in triplicate in a 96-well plate in 100 μl of complete DMEM. At 24 h after seeding, cells were either left untreated or exposed to doxorubicin, etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich), or an ATM kinase inhibitor (KU-55933; EMD) at a predetermined concentration. Four days (96 h) after drug treatment, CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) was added to each well, and the luminescence signal intensity was measured with a BMG POLARstar Omega plate reader. The readouts from drug-treated wells were normalized against those from untreated controls. The normalized values represent the measures of drug sensitivity and were expressed as fraction of survival, which, along with standard deviations, were plotted against drug concentration.

Cell proliferation assay.

Cells (5,000 cells/well) were seeded in triplicate in a 96-well plate as described above. Relative cell numbers were assessed at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after seeding using CellTiter-Glo reagent as described above. The luminescence readout at each time point was normalized against the corresponding initial readout at time zero. The resulting values were averaged and plotted against times to generate the growth curve.

Immunoprecipitation (IP).

HCT116 cells with stable expression of an Ad12 E1B-55K construct were harvested in buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 150 mM KCl, and a 100-fold-diluted protease inhibitor cocktail [P8340; Sigma-Aldrich]). The cell lysates were frozen at −80°C and thawed at room temperature. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,500 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants (containing 5 mg of total proteins) were mixed with 10 μl of rabbit antiserum raised against Ad12 E1B-55K as described previously (27). After rotation overnight at 4°C, 50 μl of protein G-agarose slurry (Roche Applied Science) was added and rotated further for 2 h at 4°C. The mixture was centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 2 min, and the supernatant was removed. The beads were washed four times with buffer B and resuspended in 60 μl of 1× SDS sample buffer. The immunoprecipitates along with input cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting using mouse monoclonal anti-p53 antibody (DO-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

RESULTS

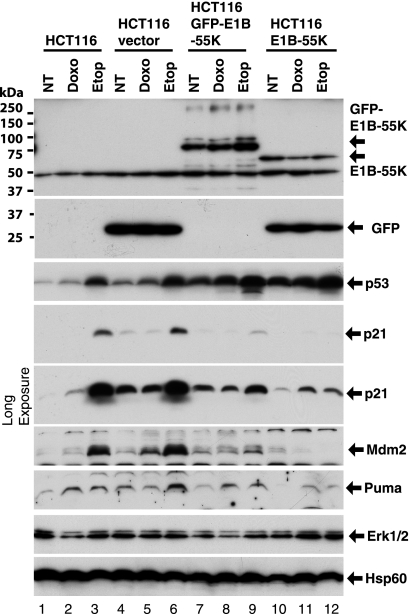

Expression of Ad12 E1B-55K protein attenuates activation of p53 target genes in HCT116 cells after drug treatment.

We transduced HCT116 cells with a lentiviral vector for constitutive expression of Ad12 E1B-55K protein. Stable cell lines expressing GFP (vector), GFP-E1B-55K, or wt E1B-55K were obtained after puromycin selection (Fig. 1, top two panels). Parental HCT116 cells or derived cell lines were exposed to doxorubicin or etoposide, two genotoxic chemotherapeutic agents that activate the p53 pathway. As shown in Fig. 1, after drug treatment, whereas the GFP-E1B-55K or E1B-55K levels remained relatively constant, p53 protein levels were increased. Several p53 target genes, including those for p21, Mdm2, and Puma were clearly activated in the parental cells (compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1). In cells transduced with lentiviral vector expressing GFP, similar effects were also detected (lanes 4 to 6; note that basal levels of p53, p21, and Puma were slightly increased, but all three p53 target genes were clearly activated in etoposide-treated cells). In contrast, in HCT116 cells expressing GFP-E1B-55K, induction of the p21 and Mdm2 genes was clearly reduced (Fig. 1, lanes 7 to 9). In HCT116 cells stably expressing wt E1B-55K, the expression of all three target genes, encoding p21, Mdm2, and Puma, was suppressed compared to that in parental or vector-transduced cells (Fig. 1, lanes 10 to 12). Repression of p53 target genes was not due to reduced levels of p53 protein. In fact, p53 was stabilized in cells expressing GFP-E1B-55K or wt E1B-55K, and drug treatment led to a further increase of p53 (Fig. 1). Thus, Ad12 E1B-55K could inhibit p53 despite the presence of high levels of p53, consistent with the model that E1B-55K exerts repression through binding to p53's transactivation domain and perhaps also by recruiting a corepressor complex (1, 57).

Fig. 1.

Repression of p53 target genes by Ad12 E1B-55K protein. Colon carcinoma cell line HCT116 was stably transduced with lentiviral vector expressing GFP (HCT116 vector), a GFP-Ad12 E1B-55K fusion (HCT116 GFP-E1B-55K), or wt Ad12 E1B-55K in addition to GFP, in which the coding sequences of E1B-55K and GFP are separated with an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) (HCT116 E1B-55K). The parental line along with the derived stable cell lines were untreated (NT) or treated with doxorubicin (Doxo) (0.1 μM) or etoposide (Etop) (1 μM) for 24 h. The cells were harvested for Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. In each lane, 30 μg of total cellular proteins was loaded. The blots were probed with extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (Erk1/2) and mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) as loading controls. For the p21 blot, two different exposures are shown. For the E1B-55K blot, the samples were unheated to avoid the formation of E1B-55K aggregates at high temperature.

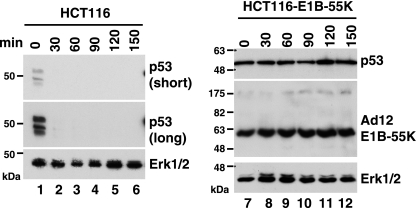

Metabolic stabilization of p53 by Ad12 E1B-55K in HCT116 cells.

p53 is an unstable protein due to rapid ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation (6). Since E1B-55K expression resulted in elevation of p53 protein levels, we wished to assess metabolic stability of p53 in the presence of E1B-55K. As shown in Fig. 2, p53 was rapidly degraded within 30 min after the addition of cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, in HCT116 cells (Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 6). In contrast, no degradation of p53 was evident within the 150-min chasing period in HCT116-E1B-55K cells that constitutively express Ad12 E1B-55K (Fig. 2, lanes 7 to 12). Stabilization of p53 by Ad12 E1B-55K in other cell types has been reported previously (15), indicating that E1B-55K-mediated p53 stabilization is a general phenomenon. Notably, E1B-55K itself was quite stable, as there was no noticeable reduction of its protein abundance during the chasing period (Fig. 2). Mdm2 is a major E3 ubiquitin ligase of p53 that mediates p53 ubiquitination (6). Stabilization of p53 in the presence of E1B-55K may be attributed to the suppressed Mdm2 expression (Fig. 1). In addition, E1B-55K might also compete against Mdm2 for binding to p53, as they bind to overlapping regions within the N-terminal transactivation domain of p53 (28). Thus, E1B-55K appears to be a particularly strong stabilizer of p53.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic stabilization of p53 by Ad12 E1B-55K protein. HCT116 parental cells and the HCT116-E1B-55K cell line stably expressing Ad12 E1B-55K were exposed to 25 μg/ml of cycloheximide, and at the indicated time points after its addition, cells were harvested for Western blotting with the monoclonal anti-p53 antibody DO-1. E1B-55K was detected using unheated samples with an anti-Ad12 E1B-55K antiserum. Equal amounts (30 μg) of total cellular proteins were loaded in each lane. Two different exposures of the p53 blot are shown for HCT116 cell extracts. The membranes were reprobed with anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control.

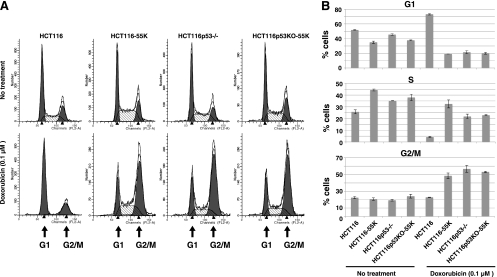

E1B-55K suppresses p53-mediated cell cycle regulation.

p53 elicits G1 cell cycle arrest by activating the expression of p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases (11). The results shown in Fig. 1 indicate that E1B-55K repressed p53-mediated activation of the p21 gene. This suggests that E1B-55K could block p53-mediated cell cycle arrest. To test this, HCT116 cells and their isogenic counterpart HCT116p53−/− cells, in which both alleles of the p53 gene were inactivated through homologous recombination (7), in the absence or presence of Ad12 E1B-55K expression, were left untreated or exposed to 0.1 μM doxorubicin and then subjected to cell cycle analysis. In untreated subconfluent cells, ∼52% of cells in the parental HCT116 cell line were in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 3). Expression of E1B-55K in HCT116 cells (HCT116-55K) reduced the portion of cells in G1 to ∼35%. The percentage of cells in the G1 phase in HCT116p53−/− cells and their derivative with E1B-55K expression (HCT116p53KO-55K) was also lower than that in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3B) (45% or 38% versus 52%) but was slightly higher than that in HCT116-55K cells (Fig. 3B) (45% or 38% versus 35%). Notably, higher proportions of cells in the S phase were seen among HCT116-55K, HCT116p53−/−, and HCT116p53KO-55K cells than among the parental HCT116 cells, but the proportions of cells with G2/M content were largely similar (Fig. 3). Thus, it seems apparent that the expression of E1B-55K had a profound impact on cell cycle kinetics in cells with p53 but exerted a much smaller influence on cell cycling behavior in the absence of p53 in cells undergoing active proliferation under normal culture conditions. These results imply that through inhibition of p53, E1B-55K disables the G1/S checkpoint and promotes S-phase entry. In agreement with the latter point, Hutton et al. reported that disruption of the interaction of p53 with E1B-55K in Ad E1-transformed cells using a peptide derived from the p53-binding core of Ad5 or Ad12 E1B-55K reduced cellular DNA synthesis (22).

Fig. 3.

Deregulation of cell cycle control by Ad12 E1B-55K protein. Subconfluent cultures of the HCT116 parental cell line and the isogenic line HCT116p53−/− or their derivatives with stable E1B-55K expression were untreated or exposed to 0.1 μM doxorubicin. After 24 h, cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. (A) Representative cell cycle profiles of these cell lines with or without drug treatment are shown. (B) Quantitative distributions in different phases of the cell cycle of the indicated cell lines. Shown are average values from two independent experiments along with standard deviations.

To further assess the effects of E1B-55K on cell cycle progression, we treated cells with doxorubicin. As shown in Fig. 3, doxorubicin treatment profoundly altered cell cycle profiles. In HCT116 cells, exposure to doxorubicin resulted in markedly increased proportions of cells in the G1 phase (∼73%), with concomitant reduction of proportions of cells with S content. In contrast, doxorubicin treatment of HCT116-55K, HCT116p53−/−, or HCT116p53KO-55K cells led to large G2/M peaks and a markedly reduced proportion of cells with G1 content. Notably, substantial proportions of the cells remained in the S phase in these derived cells compared to the parental HCT116 cells. Thus, HCT116 cells with E1B-55K expression behaved essentially like HCT116p53−/− cells on challenge by a DNA-damaging agent, suggesting that E1B-55K profoundly suppressed p53-mediated cell cycle regulation. Nonetheless, there was a higher percentage of cells in the S phase accompanied by a lower percentage of cells in the G2/M phase among HCT116-55K cells than among HCT116p53−/− and HCT116p53KO-55K cells (Fig. 3). Thus, it is possible that the presence of p53 might even facilitate E1B-55K promotion of cell cycle progression.

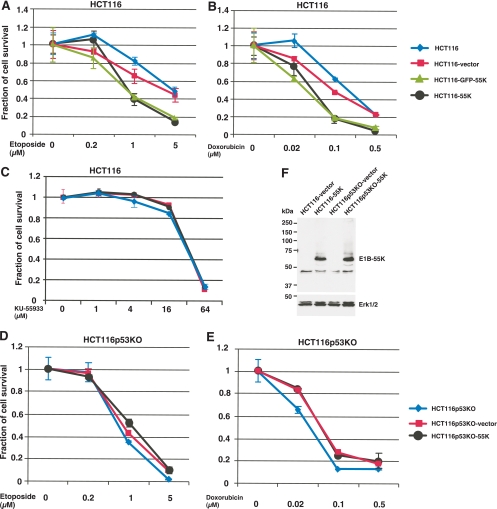

E1B-55K enhances genotoxic agent-induced cytotoxicity.

In response to DNA damage, p53 induces transient cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, which allows for the repair of DNA damage and cell survival, thereby reducing the potency of certain anticancer agents. The data presented above (Fig. 1 and 3) show that E1B-55K is a strong inhibitor of p53 and largely negates p53-mediated cell cycle control. Thus, we reasoned that E1B-55K expression should potentiate the cytotoxicity of DNA-damaging drugs. To test this idea, we treated HCT116 cells and several derivatives stably transduced with a lentiviral vector control (HCT116-vector) or carrying cDNA encoding wt Ad12 E1B-55K (HCT116-55K) or a GFP-E1B-55K fusion (HCT116-GFP-55K) with doxorubicin or etoposide, two DNA topoisomerase II (Topo II) inhibitors that cause double-strand DNA breaks (9, 26). As shown in Fig. 4, expression of E1B-55K or its fusion with GFP in HCT116 cells resulted in reduced cell survival compared to that of parental HCT116 or vector-transduced cells after exposure to various doses of etoposide or doxorubicin (Fig. 4A and B). To test whether E1B-55K-mediated sensitization is drug specific, we also treated these cell lines with the ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) inhibitor KU-55933 (20). The data presented in Fig. 4C demonstrated that all these cell lines, regardless of E1B-55K expression, exhibited similar sensitivity to KU-55933. Thus, it appears likely that E1B-55K enhances the killing effects of only a certain class of chemotherapeutic drugs, especially genotoxic agents. Of note, our results (Fig. 1 and 4) also indicate that the attachment of a GFP moiety to the N terminus of Ad12 E1B-55K largely did not alter the function of this viral protein to inhibit p53. Additionally, we found that both GFP-E1B-55K and E1B-55K stimulated Ad DNA replication to similar extents (D. Liao et al., unpublished data).

Fig. 4.

Ad12 E1B-55K protein sensitizes HCT116 cells to genotoxic agents. HCT116 parental cell line and the isogenic line HCT116p53−/− (HCT116p53KO) or their derivatives that were stably transduced with vector (HCT116-vector) or that expressed Ad12 E1B-55K (HCT116-55K) or a GFP-E1B-55K fusion (HCT116-GFP-55K) were untreated or exposed to various doses of etoposide, doxorubicin, or KU-55933. The fractions of viable cells after exposure to drug for 96 h were determined and are plotted against drug concentrations. Shown are average values from three independent experiments along with standard deviations. (A to C) Effects of E1B-55K expression in HCT116 cells on sensitivity to etoposide (A), doxorubicin (B), or KU-55933 (C). (D and E) Effects of E1B-55K expression in HCT116p53−/− (HCT116p53KO) cells on sensitivity to etoposide (D) or doxorubicin (E). (F) Expression levels of E1B-55K in HCT116 and HCT116p53−/− (HCT116p53KO) cells.

To assess whether inhibition of p53 by E1B-55K per se is responsible for chemosensitization, the sensitivity of the HCT116p53−/− cell line or a counterpart line with stable Ad12 E1B-55K expression (HCT116p53KO-55K) to etoposide and doxorubicin was examined. As shown in Fig. 4D and E, the absence of p53 in HCT116 cells rendered the tumor cells markedly more sensitive than the isogenic HCT116 cells to both doxorubicin and etoposide, and E1B-55K expression did not enhance cytotoxicity. Notably, the HCT116p53−/− cells transduced with vector only (HCT116p53KO-vector) or with E1B-55K (HCT116p53KO-55K) were slightly more resistant to both drugs than the parental HCT116p53−/− cells, but it is clear that E1B-55K expression had no additional effects on drug sensitivity in HCT116p53−/− cells. E1B-55K was expressed at similar levels in the HCT116-55K and HCT116p53KO-55K cell lines (Fig. 4F), indicating that the loss of effects on drug sensitization by E1B-55K in HCT116p53−/− cells was not due to reduced expression. We therefore conclude that E1B-55K-mediated chemosensitization of doxorubicin and etoposide was specifically due to inhibition of p53 by this viral protein.

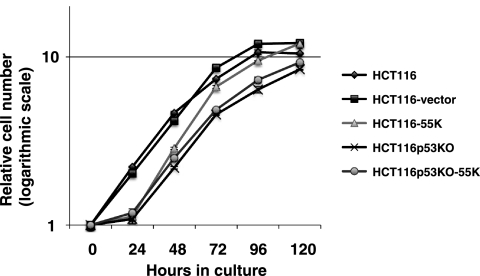

Chemosensitization by E1B-55K could be due to accelerated cell proliferation, as active proliferating cells are generally more susceptible to genotoxic drugs than quiescent cells. We assessed the relative rate of cell proliferation of HCT116 cells and the derivative cell lines. As shown in Fig. 5, within the linear range of the growth curves (24 to 72 h), the lines are largely parallel for HCT116, HCT116-vector, HCT116p53KO, and HCT116p53KO-55K, indicating similar rates of proliferation. Notably, within this range, the slope of the line representing HCT116-55K is slightly greater, suggesting a higher rate of proliferation for this cell line. Interestingly, there was a clear offset over the first 24 h postplating for the HCT116-55K, HCT116p53KO, and HCT116p53KO-55K cell lines. Thus, with the exception of an initial lag immediately after plating, E1B-55K expression in HCT116 cells was able to increase the rate of proliferation, which depended on p53, as E1B-55K expression did not influence the proliferation rate of the isogenic HCT116p53−/− cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of E1B-55K expression on cell proliferation. The parental HCT116 cell line and the indicated derivatives were seeded in equal number in triplicate in a 96-well plate. At the indicated time points, relative cell numbers were determined using a CellTiter-Glo kit. The average relative cell numbers along with standard deviations are plotted against time on a semilogarithmic scale.

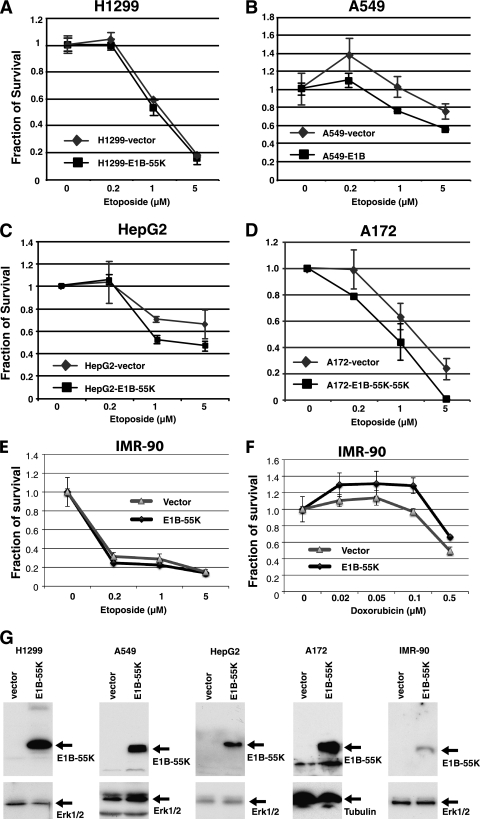

To assess effects of E1B-55K expression on drug sensitivity in other types of tumor cells, we stably transduced a lentiviral vector expressing GFP alone (control) or carrying an E1B-55K expression cassette along with GFP in H1299 and A549 (non-small-cell lung cancer), HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), and A172 (glioblastoma) cells. All these cell lines except H1299, which is deficient in p53, express wt p53. The data presented in Fig. 6 show that the expression of Ad12 E1B-55K sensitized A549, HepG2, and A172 cells to etoposide compared to the control. However, E1B-55K expression had no effects on drug sensitivity in H1299 cells. Consistent with the results shown above, these findings provide further support for the notion that inhibition of p53 by E1B-55K sensitizes tumor cells with functional p53 to chemotherapeutic agents that cause DNA damage.

Fig. 6.

Ad12 E1B-55K protein sensitizes diverse tumor cells to genotoxic agents. Non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines H1299 and A549, hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2, and glioblastoma cell line A172 were stably transduced with empty vector or that expressing Ad12 E1B-55K. These stable cell lines were exposed to various doses of etoposide, and their drug sensitivity was determined as for Fig. 4. Shown are average values from three independent experiments along with standard deviations. (A to D) Effects of E1B-55K expression in H1299 (A), A549 (B), HepG2 (C), or A172 (D) cells on sensitivity to etoposide. (E and F) Normal human fetal lung fibroblast cell line IMR-90 was transfected with an empty vector (vector) or a vector expressing E1B-55K. The transfected cells were treated with dosed etoposide (E) or doxorubicin (F). (G) The expression of E1B-55K in these cell lines was assessed by Western blotting.

To assess potential effects of E1B-55K expression on untransformed cells, we transfected IMR-90, a human fetal lung fibroblast cell line, with vector control or Ad12 E1B-55K plasmid. The transfected cells were exposed to etoposide or doxorubicin as for Fig. 4. The data presented in Fig. 6E indicate that IMR-90 cells were sensitive to etoposide and that E1B-55K expression did not obviously sensitize the cells to this drug, compared to the vector control. Figure 6F shows that IMR-90 cells were quite resistant to doxorubicin, and E1B-55K expression afforded moderate protection against this drug. Of note, E1B-55K was expressed well in all the studied cell lines (Fig. 6G). Collectively these results suggest that E1B-55K selectively sensitizes tumor cells to genotoxic drugs.

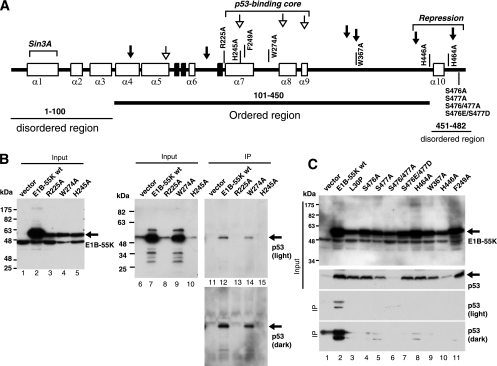

Impact of mutations of conserved residues of E1B-55K on interaction with p53.

Among the E1B-55K proteins from at least 50 serotypes of human Ads (divided into groups A to G), the sequences are highly conserved in roughly two-thirds of the proteins toward the C terminus (27). N-terminal stretches of ∼40 residues are also conserved, although to a much lesser degree, whereas the sequences between these two conserved blocks are highly variable. One notable feature of the C-terminal conserved block is the presence of multiple invariable Phe, Trp, Cys and His residues. These conserved residues might have functional significance. In particular, since the p53-binding site is located within the conserved region of E1B-55K, mutation of certain conserved residues might affect its interaction with and inhibition of p53, consequently affecting chemosensitization. We therefore selectively mutated some of them to Ala. The mutations we introduced are concentrated in the p53-binding core, with several others near the C terminus (Fig. 7A). To assess potential effects of these mutations on the interaction of E1B-55K with p53, we conducted coimmunoprecipitation experiments using cell extracts stably expressing this panel of E1B-55K variants (Fig. 7B and C). Notably, p53 protein levels varied considerably in HCT116 cells expressing these E1B-55K variants (Fig. 7B and C). Expression of wt E1B-55K and most of the mutants (L30P, F249A, W274A, W367A, H464A, S476A, S477A, and S476E/S477D) resulted in increased levels of p53 (Fig. 7B and C). Among this group of E1B-55K constructs, only wt E1B-55K and the W274A mutant were able to coprecipitate with p53 (Fig. 7B, lanes 11 and 14, and C, lane 2). The other mutants exhibited no or drastically reduced coprecipitation with p53. The second group of E1B-55K mutants, including R225A, H245A, H446A, and S476A/S477A, did not elevate p53 protein levels. These E1B-55K variants did not coprecipitate with p53 (Fig. 7B and C). However, because of the markedly lower levels of p53 in cells expressing the latter group of E1B-55K variants, it remains uncertain whether the corresponding mutations indeed negatively affect p53-E1B-55K interaction.

Fig. 7.

Coprecipitation of wt Ad12 E1B-55K and various mutants with p53. (A) Predicted secondary structural elements based on Chou-Fasman and Robson-Garnier methods as implemented in the MacVector software. White and black boxes denote α helices and β strands, respectively. Nonstructured or loop-turn regions are shown as thick lines. Corresponding positions of linker insertions within Ad2 E1B-55K are indicated with arrows (51). Insertions that suppressed the interaction of Ad2 E1B-55K with p53 are denoted with arrows with open heads and those that did not affect this interaction with black arrows. The Sin3A-binding site near the N terminus, the C-terminal repression domain, and the p53-binding core region are indicated. Bioinformatics prediction using the PONDR program (Molecular Kinetics, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) indicates that the central part (amino acids [aa] 100 to 450, thick underline) of Ad12 E1B-55K is possibly ordered, whereas the N-terminal region (aa 1 to 100, thin underline) and the C-terminal tail (aa 450 to 482, thin underline) may be disordered. (B and C) Vector-transduced HCT116 cells (vector) or those transduced with a vector expressing wt E1B-55K or a specific mutant as indicated were subjected to IP with a rabbit anti-E1B-55K antiserum. The immunoprecipitates were extensively washed and then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the coprecipitated p53 was examined using Western blotting. Cell extracts (input, about 5% of materials used for IP) were also loaded in the gels. The E1B-55K blots were done using unheated samples as for the other figures. Two exposures of the IP blots are shown. The results shown are representative of three independent IP experiments.

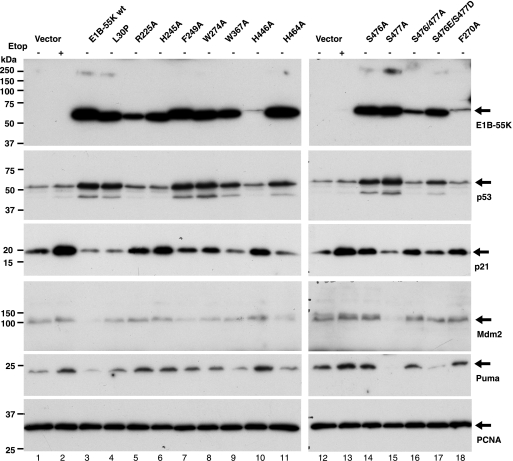

p53 stabilization by E1B-55K mutants.

Although E1B-55K together with E4orf6-34K protein mediates polyubiquitination of p53 that eventually leads to its proteasomal degradation (19, 32, 38), expression of E1B-55K of Ad2, Ad5, or Ad12 alone appears to result in elevated protein abundance of p53 (1, 15, 25, 39, 43), suggesting that E1B-55K might directly or indirectly stabilize p53. As shown above (Fig. 1, 2 and 7), we confirmed that expression of wt Ad12 E1B-55K resulted in marked stabilization of wt p53. As mutations at various positions within the Ad12 E1B-55K protein differentially affected its binding affinity to p53 (Fig. 7), we assessed how these mutations might affect E1B-55K-mediated stabilization of p53. p53 protein levels were determined in HCT116 cells stably expressing these E1B-55K mutants. As shown in Fig. 7 and 8, out of the 13 mutants of E1B-55K we examined, eight (L30P, F249A, W274A, W367A, H464A, S476A, S477A, and S476E/S477D) stabilized p53. Notably, five mutants (R225A, H245A, F270, H446A and S476A/S477A) did not stabilize p53 (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the S476A/S477A double mutant was defective in p53 stabilization, but single mutations of these two Ser residues or conversion of both to phosphomimetic residues (S476E/S477D) did not affect the ability of E1B-55K to stabilize p53, suggesting that phosphorylation at at least one of the two sites might be important for E1B-55K to induce p53 stabilization.

Fig. 8.

Effects of E1B-55K mutations on p53 stabilization and activity. HCT116 cells were stably transduced with vector expressing wt Ad12 E1B-55K or the indicated point mutant. As a positive control for p53 activation, the vector-transduced HCT116 cells were exposed to etoposide at 1 μM as indicated for 24 h. The cell extracts of these stable cell lines as well as the parental cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Equal amounts of total extracts were loaded in each lane. PCNA was detected as a loading control.

We also examined p53 transactivation activity in cells expressing wt and mutant E1B-55K. The expression of p53 target genes, including the p21, Mdm2, and Puma genes, was assessed. To facilitate comparison of p53 activity across various cell lines expressing different E1B-55K constructs, we treated vector-transduced HCT116 cells with 1 μM etoposide as a positive control for p53 activation. Compared to that in untreated control cells (Fig. 8, lane 1), the levels of p21 protein were lower in cells expressing wt E1B-55K (lane 3), L30P (lane 4), W367A (lane 9), H464A (lane 11), and S477A (lane 15), although all these E1B-55K constructs could stabilize p53. Thus, p53-mediated activation of the p21 gene was actively suppressed by these E1B-55K constructs. Among this panel of E1B-55K constructs, the wt and the S477A mutant appeared to be most repressive, as they suppressed the basal-level expression of p21, Mdm2, and Puma (compare lanes 3 and 15 with lane 1). Other E1B-55K constructs such as F249A, W274A, W367A, H464A, and S476E/S477D permitted basal levels of expression for these p53 target genes but prevented their activation, despite heightened p53 protein abundance, suggesting that p53 activity is largely inhibited by these E1B-55K constructs. In contrast, expression of several other E1B-55K mutants, namely, R225A (lane 5), H245A (lane 6), H446A (lane 10), S476A (lane 14), S476/477A (lane 16), and F270A (lane 18), permitted moderate activation of these p53 target genes. Among cell lines expressing the latter E1B-55K constructs, p53 was not or was only slightly stabilized, except for the HCT116-S476A cell line, in which the p53 level was clearly increased. Thus, E1B-55K mutants R225A, H245A, H446A, and F270A might potentially activate these genes in a p53-independent manner, although further studies are required to confirm this notion. Taken together, these results suggest that p53 was inactive in HCT116 cells expressing most of these 13 E1B-55K mutants despite elevated levels of p53.

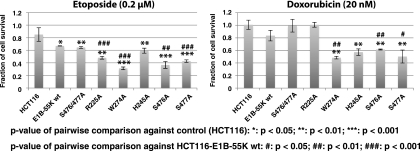

Drug sensitivity of HCT116 cells expressing various E1B-55K mutants.

The data presented above demonstrated that E1B-55K sensitized tumor cells to the genotoxic drugs doxorubicin and etoposide, possibly through inhibition of p53. To test potential effects of mutations at conserved residues of E1B-55K on drug sensitization, parental HCT116 cells and the derivatives expressing wt E1B-55K or a variant as described above were untreated or exposed to a low dose of doxorubicin (20 nM) or etoposide (0.2 μM). Cell viability was determined at 4 days after drug addition. As shown in Fig. 9, all the E1B-55K constructs we tested reduced cell viability after exposure to etoposide compared to parental HCT116 cells. E1B-55K mutants W274A, H245A, S476A, and S477A also sensitized cells to 20 nM doxorubicin, although mutants R225A and S476A/S477A did not enhance toxicity of this drug. Compared to the control (HCT116 cells without E1B-55K expression), wt E1B-55K slightly enhanced toxicity to 20 nM doxorubicin, although this sensitization is not statistically significant, consistent with the results shown in Fig. 4. Since some of these mutants, such as S477A, could still suppress p53-mediated gene activation, these results are consistent with the notion that inhibition of p53 by E1B-55K results in chemosensitization. Nonetheless, as other mutants, such as R225A and H245A, appeared to exert p53-independent effects, they might possibly provoke chemosensitization via p53-independent pathways.

Fig. 9.

Chemosensitization by Ad12 E1B-55K mutants. The parental HCT116 cell line and a panel of derived cell lines expressing wt Ad12 E1B-55K or the indicated mutant as in Fig. 8 were untreated (NT) or exposed to the indicated dose of doxorubicin or etoposide. Cell viability was assessed as for Fig. 4. Shown are average values from three independent experiments along with standard deviations. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated here that inhibition of p53 by E1B-55K potentiated chemotherapeutic agent-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 4, 6, and 9). E1B-55K suppressed p21 gene expression (Fig. 1 and 8) and the p53-dependent cell cycle checkpoint at the G1 phase (Fig. 3), which seems to directly correlate with E1B-55K-mediated chemosensitization. Along this line, it is noteworthy that expression of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) E6 oncoprotein, which promotes ubiquitin-mediated p53 degradation (34), enhanced cytotoxicity to the DNA-alkylating agent 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) in glioblastoma cells (49). Furthermore, it has been shown that the clinical outcomes after treatment with cisplatin and radiation therapy were significantly better in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients with HPV-positive tumors than in those with HPV-negative tumors (8, 12). Thus, E6-mediated ablation of p53 might be an important factor in enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy. Although E1B-55K and E6 inhibit p53 through very different mechanisms, both viral proteins can sensitize tumor cells to conventional chemotherapy. Unlike HPVs, available data show that Ads are safe in human clinical trials and that Ads are not directly associated with cancer etiology in humans. Thus, E1B-55K might represent a potential sensitizer for possible clinical applications to enhance anticancer chemotherapy, while avoiding potential oncogenic risk. To advance the potential translational application of E1B-55K as an adjuvant in clinical chemotherapy, it should ideally enhance cytotoxicity only of tumor cells to conventional chemotherapeutic drugs with minimal effects on normal cells. We addressed this issue by assessing the effects of E1B-55K expression on normal IMR-90 lung fibroblasts after exposure to etoposide and doxorubicin. Whereas E1B-55K moderately attenuated the toxicity of doxorubicin to IMR-90 cells, it did not affect the sensitivity of IMR-90 cells to etoposide (Fig. 6). Although these observations provide initial support for possible clinical application of E1B-55K as an adjuvant in combination with these genotoxic drugs, the unexpected high sensitivity of IMR-90 cells to etoposide under our experimental conditions might limit the utility of a combination therapy with etoposide and E1B-55K. Clearly, further studies will be required to assess the safety and efficacy of etoposide, doxorubicin, and other genotoxic drugs in combination with E1B-55K expression using diverse types of normal human cells as well as in vivo using an animal model.

Although the data presented here are consistent with our model that E1B-55K sensitizes tumor cells to genotoxic agents by inhibiting the prosurvival function of p53, alternative interpretations also exist. E1B-55K might synergize with p53 to kill tumor cells in response to DNA-damaging signaling. Indeed, E1B-55K expression appeared to enhance the proliferation of HCT116 cells but not the isogenic HCT116p53−/− cells (Fig. 5). It will be interesting to conduct kinetic analysis of the growth behaviors of HCT116 and HCT116p53−/− cell lines with or without the expression of E1B-55K to definitively determine its impact on the rate of proliferation. Additionally, whereas p53 target genes are suppressed in cells expressing E1B-55K or some of its variants, p53 possesses a transactivation-independent function to promote apoptosis by modulating the activities of Bcl-2 families of proteins (16). Nonetheless, we showed previously that sequestration of p53 in the cytoplasm by E1B-55K inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis (55). However, p53 can potentiate cell death indirectly through other means, including transcriptional repression in the nucleus and inhibition of autophagy in the cytoplasm (16). Further studies will be required to clarify whether E1B-55K could suppress diverse cellular functions of p53.

We have conducted co-IP to assess the interaction between p53 and a panel of Ad12 E1B-55K variants. Association between p53 and wt E1B-55K was consistently detected (Fig. 7). Although our data indicate that the interaction between Ad12 E1B-55K and p53 seems to be quite sensitive to mutations within the Ad12 E1B-55K protein, direct comparison of the affinity to p53 of the panel of E1B-55K variants reported here is complicated due to uneven levels of p53 in cells expressing them. Moreover, it has been noted that Ad12 E1B-55K has lower binding affinity to p53 than the Ad5 ortholog. Thus, mutations within Ad12 E1B-55K could have more profound effects on its interaction with p53 than corresponding mutations in Ad5 E1B-55K.

Consistent with studies by others (15), here we demonstrated that expression of Ad12 E1B-55K results in p53 stabilization in tumor cell lines with wt p53. Notably, in the colon cancer cell line HCT116 with E1B-55K expression, p53 exhibited extraordinary metabolic stability. No apparent turnover was observed under our experimental conditions. How does E1B-55K stabilize p53? Several models exist. First, direct binding between p53 and E1B-55K protects p53 from degradation. This mechanism seems unlikely according to our results. As discussed above, mutation of conserved residues in E1B-55K significantly impairs its ability to directly bind p53 in HCT16 cells. However, although unable to bind p53, some of these mutants could stabilize p53 as well as wt E1B-55K (Fig. 7 and 8). Thus, direct binding does not seem to be essential for E1B-55K to stabilize p53. Nonetheless, we could not exclude the possibility that mutants that stabilized p53 might still interact with it dynamically, thereby protecting p53 from degradation. Second, E1B-55K might inhibit cellular factors such as Mdm2 that promote p53 degradation, resulting in p53 stabilization. If this model is correct, the Ad12 E1B-55K mutants that are unable to stabilize p53 might be defective for inhibiting such cellular factors. In addition to Mdm2, there are multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases that promote p53 polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (reviewed in reference 6). In principle, inhibition of any of these p53 degradation pathways by E1B-55K could stabilize p53. In Ad-infected cells at a late stage during lytic infection, the vast majority of E1B-55K exists in a complex with E4orf6-34K (1). This complex is assembled with several cellular proteins, including Elongins B and C, Cullin-5, and Rbx-1, to form a functional E3 ubiquitin ligase. This E3 complex specifically degrades p53 in infected cells, and E1B-55K is the substrate recognition subunit (19, 32). In the absence of E4orf6-34K, this degradation mechanism does not operate. Instead, p53 is stabilized when only E1B-55K is expressed, as we demonstrated in this study. It remains an open question whether E1B-55K might stabilize p53 through perturbing additional E3 ligases such as the Cullin-containing complexes or even by inhibiting ubiquitin-independent mechanisms. Perturbation of other cellular pathways could also tip the balance of p53 homeostasis toward its stabilization. We observed previously that E1B-55K binds Daxx (54), and a recent study showed that E1B-55K could promote Daxx degradation in the absence of E4orf6-34K during adenovirus infection (35). Daxx binds to Mdm2 (56), and they cooperate to promote p53 degradation (40). Thus, it is possible that E1B-55K-mediated degradation of Daxx might indirectly stabilize p53.

Alternatively, E1B-55K might be able to trigger a DNA-damaging signal, indirectly leading to posttranslational modifications of p53 and its stabilization. Previous studies showed that Ad12 E1B-55K plays a key role in inducing metaphase chromosomal fragility during Ad12 infection (27, 53). Whether this is a cause or a consequence of a DNA-damaging signaling pathway remains to be determined. It is conceivable that the expression of Ad12 E1B-55K directly or indirectly activates the cellular DNA damage response, resulting in p53 stabilization. Interestingly, Blackford et al. reported that Ad12 infection induces hyperphosphorylation of RPA32, a component of a trimeric complex that binds single-stranded DNA during DNA synthesis (4). In contrast, Ad5 infection elicits only weak RPA32 phosphorylation (4). RPA32 hyperphosphorylation appears to be mediated through ATM-Rad3-related (ATR) kinase and requires E1B-AP5, an E1B-55K-binding protein (4, 13). Thus, it can be speculated that E1B-55K could engage ATR and other kinases to modify p53 posttranslationally, promoting its stabilization. In this context, it is interesting to note that certain E1B-55K variants that could not stabilize p53 (e.g., H245A) could still sensitize HCT116 cells to genotoxic drugs (Fig. 9). This raises the possibility that E1B-55K might impinge on other pathways in addition to p53 inhibition to promote drug sensitization. One intriguing scenario is that interaction between E1B-55K and E1B-AP5 might also affect DNA damage repair and drug sensitivity.

E1B-55K has an intrinsic transcriptional repression function (30, 31, 50, 52, 57). Biochemical experiments indicated that E1B-55K must associate with DNA-bound p53 before the assembly of the p53-activated preinitiation complex (PIC) (31). In cells, when tethered to a promoter via heterologous fusion with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain, E1B-55K exerts potent transcriptional repression (50, 52). The C-terminal domain of E1B-55K is required for repression, as several point mutations in the C-terminal domain relieved the repression function of E1B-55K (41, 42, 52, 55). Furthermore, a corepressor that copurifies with RNA polymerase II complex is important for E1B-55K-mediated repression (31). Based on these data, the current paradigm holds that E1B-55K binds to chromatin-bound p53 and blocks p53-mediated transactivation from the p53 target promoters (1). Consistently, we reported previously that E1B-55K associated with p53 on the chromatins of the promoter regions of several endogenous p53 target genes such as the p21 gene (57). Among the E1B-55K mutants that we have tested here, eight mutants were able to stabilize p53 (Fig. 7 and 8). Despite this, none of them induced obvious activation of p53 target genes such as those for p21, Mdm2, and Puma (Fig. 8). We showed that most of these mutants displayed reduced or no binding to p53 in our IP assays (Fig. 7). This raises an obvious question as to how an E1B-55K mutant defective for p53 binding could suppress p53-mediated transcription. One possibility is that these mutants could still associate with chromatin-bound p53 when the repression complex is assembled on the promoter of a p53 target gene. Alternatively, these mutants might indirectly inactivate p53, for example, by blocking acetylation of p53 required for gene activation (29), or through inhibiting basal transcription. The latter scenario seems compelling for wt E1B-55K and the S477A mutant, as both potently suppressed p21, Mdm2, and Puma gene expression (Fig. 8). Further studies will be required to address this question.

In conclusion, this study provides a new dimension for understanding the function of E1B-55K and its potential application in anticancer therapy. The physical and functional interaction between p53 and E1B-55K has inspired numerous past investigations addressing important issues ranging from roles of p53 in Ad replication to exploitation of this interaction for therapeutic purposes. The E1B-55K-deleted Ad5 (dl1520 or ONYX-015) was hypothesized to preferentially kill p53-null tumor cells (3), although later studies demonstrated that p53 status does not affect its replication efficiency (14, 18). Other studies suggested that p53 might have a positive effect on Ad replication (17). Along this line, it is interesting to note that E1B-55K appeared to require p53 to promote S-phase entry and cell proliferation (Fig. 3 and 5), which is analogous to E1A function in stimulating cellular DNA synthesis through deregulating Rb-mediated transcriptional repression. Further work will be required to determine the relative importance of the classical function of E1B-55K as a repressor of p53-dependent transcription versus a potentially novel proliferation-promoting property of this viral protein in cooperation with p53 for chemosensitization described here as well as for Ad replication. However, Ad exhibits exceedingly complex interactions with p53, and the biochemical natures of these interactions as well as their potential roles in viral replication are not completely understood. In addition to efficient degradation of p53 in cells infected with wt Ad through an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex assembled by the E1B-55K/E4orf6-34K (19, 32), other mechanisms of p53 inactivation also exist (21, 36). Because of the complex interactions between p53 and Ad, future studies of each specific interaction between p53 and various viral proteins should continue to yield important insights into the ever-complex virus-host interactions as well as translational potential of Ad-based therapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lei Zhou for help with statistical analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program, the Florida Department of Health, and Stop!Children's Cancer, Inc., and in part by Public Health Service grant CA092236 from the National Cancer Institute (D.L.). Qiang Li, Heng Yang, and Zhi Zheng each received a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berk A. J. 2005. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene 24:7673–7685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertheau P., et al. 2007. Exquisite sensitivity of TP53 mutant and basal breast cancers to a dose-dense epirubicin-cyclophosphamide regimen. PLoS Med. 4:e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bischoff J. R., et al. 1996. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science 274:373–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blackford A. N., et al. 2008. A role for E1B-AP5 in ATR signaling pathways during adenovirus infection. J. Virol. 82:7640–7652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blackford A. N., Grand R. J. 2009. Adenovirus E1B 55-kilodalton protein: multiple roles in viral infection and cell transformation. J. Virol. 83:4000–4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks C. L., Gu W. 2006. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol. Cell 21:307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bunz F., et al. 1999. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J. Clin. Invest. 104:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung C. H., Gillison M. L. 2009. Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer: its role in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 15:6758–6762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deweese J. E., Osheroff N. 2009. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep's clothing. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:738–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donehower L. A., Lozano G. 2009. 20 years studying p53 functions in genetically engineered mice. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:831–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. el-Deiry W. S., et al. 1993. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75:817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fakhry C., et al. 2008. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100:261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gabler S., et al. 1998. E1B 55-kilodalton-associated protein: a cellular protein with RNA-binding activity implicated in nucleocytoplasmic transport of adenovirus and cellular mRNAs. J. Virol. 72:7960–7971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodrum F. D., Ornelles D. A. 1998. p53 status does not determine outcome of E1B 55-kilodalton mutant adenovirus lytic infection. J. Virol. 72:9479–9490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grand R. J., Owen D., Rookes S. M., Gallimore P. H. 1996. Control of p53 expression by adenovirus 12 early region 1A and early region 1B 54K proteins. Virology 218:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Green D. R., Kroemer G. 2009. Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature 458:1127–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hall A. R., Dix B. R., O'Carroll S. J., Braithwaite A. W. 1998. p53-dependent cell death/apoptosis is required for a productive adenovirus infection. Nat. Med. 4:1068–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harada J. N., Berk A. J. 1999. p53-Independent and -dependent requirements for E1B-55K in adenovirus type 5 replication. J. Virol. 73:5333–5344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harada J. N., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Pallas D. C., Berk A. J. 2002. Analysis of the adenovirus E1B-55K-anchored proteome reveals its link to ubiquitination machinery. J. Virol. 76:9194–9206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hickson I., et al. 2004. Identification and characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase ATM. Cancer Res. 64:9152–9159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hobom U., Dobbelstein M. 2004. E1B-55-kilodalton protein is not required to block p53-induced transcription during adenovirus infection. J. Virol. 78:7685–7697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hutton F. G., Turnell A. S., Gallimore P. H., Grand R. J. 2000. Consequences of disruption of the interaction between p53 and the larger adenovirus early region 1B protein in adenovirus E1 transformed human cells. Oncogene 19:452–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim E., Giese A., Deppert W. 2009. Wild-type p53 in cancer cells: when a guardian turns into a blackguard. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komarov P. G., et al. 1999. A chemical inhibitor of p53 that protects mice from the side effects of cancer therapy. Science 285:1733–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levine A. J. 1990. The p53 protein and its interactions with the oncogene products of the small DNA tumor viruses. Virology 177:419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li T. K., Liu L. F. 2001. Tumor cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeting drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41:53–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liao D., Yu A., Weiner A. M. 1999. Coexpression of the adenovirus 12 E1B 55 kDa oncoprotein and cellular tumor suppressor p53 is sufficient to induce metaphase fragility of the human RNU2 locus. Virology 254:11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin J., Chen J., Elenbaas B., Levine A. J. 1994. Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein. Genes Dev. 8:1235–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y., Colosimo A. L., Yang X. J., Liao D. 2000. Adenovirus E1B 55-kilodalton oncoprotein inhibits p53 acetylation by PCAF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5540–5553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin M. E., Berk A. J. 1998. Adenovirus E1B 55K represses p53 activation in vitro. J. Virol. 72:3146–3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martin M. E., Berk A. J. 1999. Corepressor required for adenovirus E1B 55,000-molecular-weight protein repression of basal transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3403–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Querido E., et al. 2001. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev. 15:3104–3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sarnow P., Ho Y. S., Williams J., Levine A. J. 1982. Adenovirus E1b-58kd tumor antigen and SV40 large tumor antigen are physically associated with the same 54 kd cellular protein in transformed cells. Cell 28:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scheffner M., Huibregtse J. M., Vierstra R. D., Howley P. M. 1993. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell 75:495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schreiner S., et al. 2010. Proteasome-dependent degradation of Daxx by the viral E1B-55K protein in human adenovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 84:7029–7038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soria C., Estermann F. E., Espantman K. C., O'Shea C. C. 2010. Heterochromatin silencing of p53 target genes by a small viral protein. Nature 466:1076–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soussi T., Wiman K. G. 2007. Shaping genetic alterations in human cancer: the p53 mutation paradigm. Cancer Cell 12:303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steegenga W. T., Riteco N., Jochemsen A. G., Fallaux F. J., Bos J. L. 1998. The large E1B protein together with the E4orf6 protein target p53 for active degradation in adenovirus infected cells. Oncogene 16:349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steegenga W. T., et al. 1995. Distinct modulation of p53 activity in transcription and cell-cycle regulation by the large (54 kDa) and small (21 kDa) adenovirus E1B proteins. Virology 212:543–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang J., et al. 2006. Critical role for Daxx in regulating Mdm2. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:855–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Teodoro J. G., Branton P. E. 1997. Regulation of p53-dependent apoptosis, transcriptional repression, and cell transformation by phosphorylation of the 55-kilodalton E1B protein of human adenovirus type 5. J. Virol. 71:3620–3627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teodoro J. G., et al. 1994. Phosphorylation at the carboxy terminus of the 55-kilodalton adenovirus type 5 E1B protein regulates transforming activity. J. Virol. 68:776–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van den Heuvel S. J., van Laar T., The I., van der Eb A. J. 1993. Large E1B proteins of adenovirus types 5 and 12 have different effects on p53 and distinct roles in cell transformation. J. Virol. 67:5226–5234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Varna M., et al. 2009. p53 dependent cell-cycle arrest triggered by chemotherapy in xenografted breast tumors. Int. J. Cancer 124:991–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A. J. 2000. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408:307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vousden K. H., Lane D. P. 2007. p53 in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vousden K. H., Ryan K. M. 2009. p53 and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu G. W., Mymryk J. S., Cairncross J. G. 2005. Pharmaceutical-mediated inactivation of p53 sensitizes U87MG glioma cells to BCNU and temozolomide. Int. J. Cancer 116:187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu G. W., et al. 2001. Inactivation of p53 sensitizes U87MG glioma cells to 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. Cancer Res. 61:4155–4159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yew P. R., Berk A. J. 1992. Inhibition of p53 transactivation required for transformation by adenovirus early 1B protein. Nature 357:82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yew P. R., Kao C. C., Berk A. J. 1990. Dissection of functional domains in the adenovirus 2 early 1B 55K polypeptide by suppressor-linker insertional mutagenesis. Virology 179:795–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yew P. R., Liu X., Berk A. J. 1994. Adenovirus E1B oncoprotein tethers a transcriptional repression domain to p53. Genes Dev. 8:190–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yu A., Fan H. Y., Liao D., Bailey A. D., Weiner A. M. 2000. Activation of p53 or loss of the Cockayne syndrome group B repair protein causes metaphase fragility of human U1, U2, and 5S genes. Mol. Cell 5:801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhao L. Y., Colosimo A. L., Liu Y., Wan Y., Liao D. 2003. Adenovirus E1B 55-kilodalton oncoprotein binds to Daxx and eliminates enhancement of p53-dependent transcription by Daxx. J. Virol. 77:11809–11821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhao L. Y., Liao D. 2003. Sequestration of p53 in the cytoplasm by adenovirus type 12 E1B 55-kilodalton oncoprotein is required for inhibition of p53-mediated apoptosis. J. Virol. 77:13171–13181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao L. Y., et al. 2004. Negative regulation of p53 functions by Daxx and the involvement of MDM2. J. Biol. Chem. 279:50566–50579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhao L. Y., Santiago A., Liu J., Liao D. 2007. Repression of p53-mediated transcription by adenovirus E1B 55-kDa does not require corepressor mSin3A and histone deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 282:7001–7010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]