Abstract

The anti-glycoprotein H (gH) monoclonal antibody (anti-gH-MAb) that neutralizes varicella-zoster virus (VZV) inhibited cell-to-cell infection, resulting in a single infected cell without apoptosis or necrosis, and the number of infectious cells in cultures treated with anti-gH-MAb declined to undetectable levels in 7 to 10 days. Anti-gH-MAb modulated the wide cytoplasmic distribution of gH colocalized with glycoprotein E (gE) to the cytoplasmic compartment with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi markers near the nucleus, while gE retained its cytoplasmic distribution. Thus, the disintegrated distribution of gH and gE caused the loss of cellular infectivity. After 4 weeks of treatment with anti-gH-MAb, no infectious virus was recovered, even after cultivation without anti-gH-MAb for another 8 weeks or various other treatments. Cells were infected with Oka varicella vaccine expressing hepatitis B surface antigen (ROka) and treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks, and ROka was recovered from the quiescently infected cells by superinfection with the parent Oka vaccine. Among the genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66, transcripts of gene 63 were the most frequently detected, and products from the genes 63 and 62, but not gE, were detected mainly in the cytoplasm of quiescently infected cells, in contrast to their nuclear localization in lytically infected cells. The patterns of transcripts and products from the quiescently infected cells were similar to those of latent VZV in human ganglia. Thus, anti-gH-MAb treatment resulted in the antigenic modulation and dormancy of infectivity of VZV. Antigenic modulation by anti-gH-MAb illuminates a new aspect in pathogenesis in VZV infection and the gene regulation of VZV during latency in human ganglia.

INTRODUCTION

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection causes varicella, and then VZV becomes latent in the sensory ganglia. The reactivation of VZV caused zoster in every age group, especially in the elderly, at rates of 3 to 8 per 1,000 person-years in a study of 48,388 zoster patients (46). The major complication of zoster is chronic pain (postherpetic neuralgia); the pain is related to peripheral nerve injury and the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor by anti-immediate early (IE) 62 antibody (12). However, the mechanism of VZV latency is not clear. Studies of the latent human ganglia revealed the difference between gene regulation in VZV and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 of VZV and the product from gene 63 have been identified in latently infected human ganglia (4–7, 16, 17, 20, 22, 51), in contrast to the presence of noncoding latency-associated transcripts of HSV (29, 40).

The thymus leukemia antigen on the cell surface is lost due to anti-thymus leukemia antibody treatment, and this phenomenon is defined as the antigenic modulation of eukaryotic cells (25). Antigenic modulation also is observed in measles virus-infected cells. Antibodies to viral surface antigens modulate measles virus expression in the infected cells, and anti-hemagglutinin antibody reduces the expression of viral fusion protein, matrix protein, and phosphoprotein in measles virus-infected cells (9–11, 14, 26). The biological importance of antigenic modulation has been recognized in various cells by clearing the cell surface expression of the respective antigen with the relevant monoclonal antibody, including monoclonal antibody treatment for immunotherapy in B cells (30, 31), red blood cells (52), a human thymic myoid cell line (48), B cells (2, 3, 45), and differentiating murine embryonic stem cells and embryo fibroblasts (39).

VZV expresses the viral glycoproteins glycoprotein E (gE), glycoprotein B (gB), and glycoprotein H (gH) on the surface of infected cells. Anti-gH monoclonal antibody (anti-gH-MAb) neutralizes viral infectivity and inhibits cell-to-cell infection and plaque formation in vitro, while monoclonal antibodies to gE and gB and zoster convalescent-phase sera do not inhibit cell-to-cell infection. When infected cells were treated with anti-gH-MAb after cell-free virus infection, single-cell infection was observed without morphological changes or plaque formation (1, 41, 42). It is interesting that anti-gH-MAb confines infection to a single infected cell but that the cell does not undergo apoptosis or necrosis and lives at least a week. Therefore, we investigated the fate of single infected cells in the presence of anti-gH-MAb. The infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb expressed viral antigens with infectivity until infected cells finally became quiescent with the dormancy of VZV infectivity. Although anti-gH-MAbs might interact with gH on the cell surface, the distribution of gH was confined to the cytoplasmic compartment with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi markers near the nucleus in anti-gH-MAb-treated cells. The resultant dormant infectivity of VZV in the quiescently infected cell was recoverable by superinfection with VZV, and the gene expression of VZV was similar to that described in the analysis of latently infected human ganglia. Antigenic modulation by anti-gH-MAb modified the whole cytoplasmic distribution of gH to the cytoplasmic compartment with ER and Golgi markers, in contrast to the distribution of gE, and induced the gene expression and regulation of VZV in quiescently infected and dormant cells. Thus, the antigenic modulation of VZV-infected cells by anti-gH-MAb elucidates a new aspect in the pathogenesis of VZV infection and the gene regulation of VZV in quiescently infected cells that is similar to latency in neurons of human ganglia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human embryonic lung (HEL) cells were used to propagate a parent Oka strain, Oka vaccine virus (OkaV), and recombinant Oka varicella vaccine (ROka) expressing hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (15, 32, 33). The cell-free virus was obtained by the sonication of infected cells in the stabilizer medium (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.1% sodium glutamate, 5% sucrose, and 10% fetal bovine serum) followed by centrifugation (1, 38, 42). Briefly, when 50 to 70% cells showed cytopathology in the infected culture, the cells were suspended in PBS containing 0.1% EDTA, collected by centrifugation, and suspended in the stabilizer medium. The suspended cells were treated by an ultrasonic cell disruptor and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resultant supernatants were used as the cell-free virus stocks, and their virus titers ranged from 3.3 × 103 to 2.3 × 105 PFU/ml in this study. The Towne strain of cytomegalovirus (CMV) (18, 28) and rhinovirus 13 (13) were propagated in HEL cells, and adenovirus 5 (19) was propagated in Hep2 cells. CMV, rhinovirus 13, and adenovirus 5 were prepared from the infected cells by three cycles of freezing and thawing.

Antibodies.

The anti-gH-MAb used was clone 94, and its concentration for 50% plaque reduction was 0.12 nM (18 ng/ml), as reported previously (1, 42). Anti-gH-MAb (clone 24) and biotin-tagged anti-gH-MAb (clone 36) with an epitope different from that of clone 94 were used to produce quiescently infected cells and to detect gH in the immunofluorescent assay (IFA), respectively (1). Monoclonal antibodies specific to gB and gE were established as previously reported (24). Polyclonal antibodies against IE62 and IE63 were raised in rabbit and guinea pig, respectively, by immunization with glutathione S-transferase-fused recombinant proteins (12). To detect them, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse, rabbit, or guinea pig IgGs (Invitrogen) were used in the IFA. For double staining, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse or anti-guinea pig IgG antibody was used in combination with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-rabbit IgG or streptavidin (Invitrogen).

Time course of infectivity of infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb.

HEL cells in 12-well plates containing 1 ×105 to 2 ×105 cells per well were infected with 500 to 1,000 PFU of cell-free virus, washed with medium, and treated with maintenance medium containing 15 μg/ml anti-gH-MAb 2 or 3 h later. The cells were further cultured in the medium containing anti-gH-MAb, and the medium was replenished once a week.

The infected cells did not show any cytopathology in the presence of anti-gH-MAb (clones 24 and 94), and the infectivity of infected cells was serially examined using the infectious center assay. The infected cells were trypsinized and overlaid on fresh HEL cells in 6-cm petri dishes on days 1 to 28 after infection. The number of plaques was counted after a week of incubation without antibody.

Immunofluorescent study of fate of viral proteins.

HEL cells grown in eight-well chamber slides were infected with the parent Oka strain and treated with anti-gH-MAb (clone 94) at 15 μg/ml, and then immunofluorescence was assayed as reported previously (43, 44). At the indicated time points, cells were fixed in cold acetone-methanol (7:3) for 1 h and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the primary antibody in PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin. The coverslips then were washed twice with PBS for 5 min each and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibody. The nucleus was stained with 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). After washing again as described above, the coverslips were mounted in glycerol and examined by fluorescence microscopy. The confocal images were captured using a Leica TCS-SP5 confocal microscope and software provided by the manufacturer.

Effects of various treatments on quiescent cells infected with ROka.

Quiescently infected cells were incubated without antibody for 4 weeks. Quiescently infected cells were treated by heating at 41°C for 1 h, with 5 mM N-butyrate, or with 100 ng/ml 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (8), or they were infected with CMV, rhinovirus 13, adenovirus 5, or OkaV cell-free virus heated at 41°C for 1 h. The cells were trypsinized, overlaid on fresh HEL cells in 6-cm petri dishes, and examined for the appearance of cytopathology or VZV antigens by immunoperoxidase-stained anti-gH-MAb.

Rescue of dormant ROka infectivity by superinfection with OkaV.

ROka was constructed by replacing the thymidine kinase (TK) gene with the HBsAg gene, and therefore two markers, TK deficiency and the expression of HBsAg, were present as virus indicators. ROka in 12-well plates was infected and treated with anti-gH-MAb (clone 94) for 4 weeks to make quiescently infected cells. The quiescently infected ROka cells were superinfected with 5,000 PFU of OkaV strain per well and incubated for 2 days without anti-gH-MAb. The superinfected cells then were trypsinized and overlaid on HEL cells in 75-cm2 plastic flasks for the propagation of VZV without anti-gH-MAb. Although a mixed infection of both TK-positive and TK-deficient viruses makes the coinfected cells susceptible to acyclovir, acyclovir treatment distinguishes the cells infected with TK-deficient or -positive viruses (23, 34). Therefore, dormant ROka was isolated from plaques of the infected cells inoculated with the cell-free virus preparation of cell cultures superinfected with TK-positive virus. When 50 to 70% of cells showed cytopathology, cell-free virus was obtained by the sonication of infected cells in the stabilizer medium. Cell-free viruses prepared from superinfected cells were inoculated into HEL cells and treated with 10 μg/ml acyclovir; the plaques formed in a week were isolated by using cloning cylinders and were propagated in 25-cm2 plastic flasks. The presence of the HBsAg gene was confirmed by PCR using two primers, 5′-GGACTTCTCTCAATTTTCTAGGG-3′ and 5′-CAAATGGCACTAGTAAACTGAGC-3′, which amplify 432 bp of the HBsAg gene (27).

Analysis of VZV transcripts in quiescently infected cells.

VZV-infected HEL cells were harvested 28 days after infection. Uninfected cells were processed in parallel. Uninfected and VZV-infected cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice, and total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). Residual DNA was digested with RNase-free DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI). All RNA preparations were treated with DNase. cDNAs of transcripts were synthesized using the Prime Script first-strand cDNA synthesis kit and an oligo(dT) primer (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). PCR amplification was performed using 10% of each reverse transcription reaction mixture. The primers designed to amplify the VZV genes were described previously (5) and were obtained from Invitrogen.

The expression of the genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 was confirmed by PCR amplification using the following primers: gene 21 F (5′-TGTTGGCATTGCCGTTGA-3′) and gene 21 R (5′-ATAGAAGGACGGTCAGGAACCA-3′), gene 29 F (5′-GGCGGAACTTTCGTAACCAA-3′) and gene 29 R (5′-CCCCATTAAACAGGTCAACAAAA-3′), gene 62 3 F (5′-CGATGTAGTGATTGGACGAGACTCG-3′) and gene 62 4 R (5′-CATGTCTGGTATCCCTTGTTATG-3′), gene 63 1 F (5′-GCTTTTTAAAATCGATTTGACG-3′) and gene 63 2 R (5′-CGAGACCTTCGATTGGGTTGCC-3′), and gene 66 F (5′-CCACGTTACCGAACAGATTTATACTG-3′) and gene 66 R (5′-CTAGCTGCAAAGCGCAACCTCCCC-3′), respectively. The expression of VZV transcripts from five or six independent cultures of quiescently infected cells with anti-gH-MAb was examined.

RESULTS

Loss of infectivity of infected cells due to anti-gH-MAb.

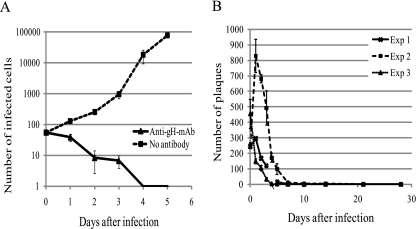

Anti-gH-MAb prevented cell-to-cell infection, and the infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb did not develop cytopathology. Anti-gH-MAb treatment reduced the number of infectious centers, but the number of infected cells increased in the culture without anti-gH-MAb treatment, as shown in Fig. 1A. Figure 1B shows the time-dependent loss of the infectivity of infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb. The number of infected cells, as determined by the infectious center assay, was reduced in a time-dependent manner, and the plaque-forming activity of the infected cells gradually declined to undetectable levels in 7 to 10 days. Infectivity was not recovered during the observation period.

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent loss of infectivity of infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb as assessed by the infectious center assay. The plaques were counted and expressed as means ± standard deviations of the number of plaques from 3 wells of 12-well plates in 6-cm dishes at each time point in three independent experiments. (A) Effect of anti-gH-MAb treatment on the number of infectious centers in infected cultures. The number of infectious centers decreased and increased in the culture treated with anti-gH-MAb (clone 24) or left untreated, respectively. (B) Fate of infectivity of infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb (clone 94). The infectivity of the treated cells had greatly decreased in a week, and plaque formation was not observed after more than 2 weeks.

Immunofluorescent study of fate of viral proteins.

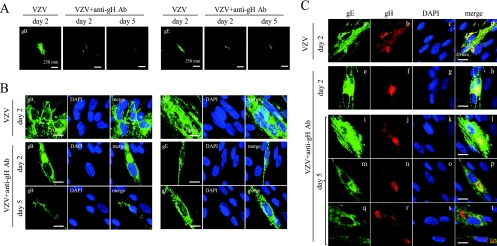

The IFA for gB, gE, and gH was performed to observe the effects of the anti-gH-MAb treatment on the expression of viral proteins in treated cells. The spread of infection was observed by the expression of gB, gE, and gH in the neighboring cells 2 days after infection without the antibody treatment (Fig. 2A). The IFA was performed to elucidate the effect of anti-gH-MAb by comparing the lytically infected cells without anti-gH-MAb on day 2 to anti-gH-MAb-treated cells on days 2 and 5 (Fig. 2B). In the presence of anti-gH-MAb, the three late antigens gB, gE, and gH were substantially expressed, but the spread of the three glycoproteins to neighboring cells was not detected throughout the experiment. While the distribution of gB and gE was cytoplasmic in infected cells left untreated or treated with anti-gH-MAb, anti-gH-MAb confined gB and gE to single infected cells 5 days after infection, in contrast to the formation of clusters of infected cells without anti-gH-MAb on day 2.

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescent analysis for gB, gE, and gH in the VZV-infected cells with and without anti-gH-MAb treatment. HEL cells inoculated with the parent Oka strain were left untreated or were treated with the anti-gH-MAb, fixed on day 2 or 5 after infection, and stained. VZV+anti-gH-MAb and VZV indicate VZV-infected cells with and without anti-gH-MAb, respectively. The expression of gB and gE in the infected cells with and without anti-gH-MAb at a lower magnification (A) and at a higher magnification (B) is shown. Viral proteins and the nucleus were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and DAPI (blue), respectively. The expression of gB and gE spread to the neighboring cells without anti-gH-MAb treatment on day 2, and anti-gH-MAb treatment confined the gB and gE expression to a single cell on days 2 and 5. (C) Modification of localization of gE and gH by treatment with anti-gH-MAb (clone 94) in the treated cells. Anti-gE-MAb and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG were used for the detection of gE, and the infected cells were stained green. Biotin-tagged anti-gH-MAb (clone 36) with an epitope different from the one in clone 94 was used with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled streptavidin, and the infected cells were stained red. (a to d) gE and gH colocalized in the cytoplasm of the infected cells on day 2 without anti-gH-MAb. (e to h) gH and gE were mostly colocalized on day 2 with anti-gH-MAb. (a, e, i, m, and q) gE was distributed widely in the cytoplasm both on days 2 and 5 with and without anti-gH-MAb. gH was relatively concentrated into the cytoplasmic compartment near the nucleus on day 2 (f) with anti-gH-MAb and mostly localized in the cytoplasmic compartment near nucleus on day 5 (j, n, and r), resulting in the loss of colocalization between gH and gE (h, l, p, and t).

Striking modulation of the localization of gH in infected cells was observed in anti-gH-MAb-treated cells on day 5. The biotin-tagged anti-gH-MAb of clone 36 recognizes different epitopes of gH than anti-gH-MAb of clone 94 in the IFA (1), and this was used to determine the localization of gH in anti-gH-MAb (clone 94)-treated cells. gH and gE mostly colocalized on day 2 without anti-gH-MAb (Fig. 2C, images a to d). gE was distributed widely in the cytoplasm on both days 2 and 5 with anti-gH-MAb (Fig. 2C, images e, i, m, and q), indicating that the distribution of gE was not influenced by treatment with anti-gH-MAb. gH was relatively concentrated into the cytoplasmic compartment near the nucleus on day 2 (Fig. 2C, image f) with anti-gH-MAb and mostly localized in the cytoplasmic compartment near nucleus on day 5 (Fig. 2C, j, n, and r). The distribution of gH was modulated and concentrated to the cellular compartment near the nucleus, but gE retained its cytoplasmic distribution on day 5 (Fig. 2C, images i to t), resulting in the loss of colocalization between gH and gE (Fig. 2C, images h, l, p, and t).

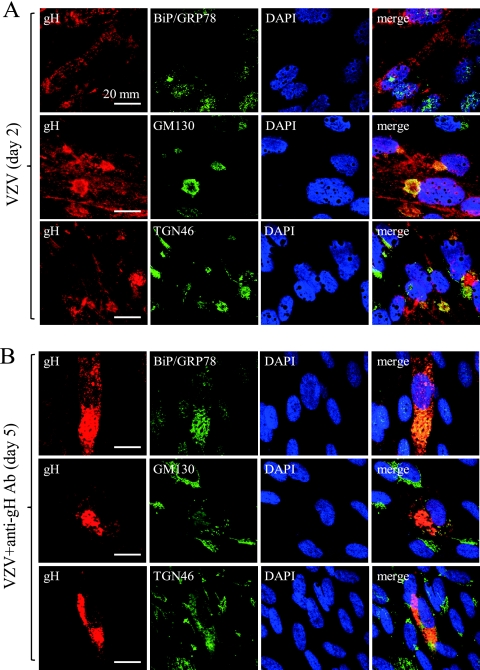

To elucidate the cytoplasmic compartment where gH was retained by treatment with anti-gH-MAb, the double staining of gH and cellular organelle markers BiP/GRP78 (ER), GM130 (cis-Golgi), and TGN46 (trans-Golgi) was performed (Fig. 3). gH was distributed to the whole cytoplasm and partly colocalized with GM130 and TGN46, but it scarcely did so with BiP/GRP78 on day 2 without anti-gH-MAb (Fig. 3A). In contrast, anti-gH-MAb treatment modulated the localization of gH, BiP/GRP78, GM130, and TGN46 to the cytoplasmic compartment near the nucleus, and gH colocalized with BiP/GRP78, GM130, and TGN46 on day 5 (Fig. 3B). gH was concentrated in the cytoplasmic compartment near the nucleus and colocalized with BiP/GRP78, GM130, and TGN46 by anti-gH-MAb treatment on day 5. gH was not colocalized with Bip/GRP78 without anti-gH-MAb on day 2 but colocalized with Bip/GRP78 with anti-gH-MAb on day 5. Thus, anti-gH-MAb induced the retention of gH within the cytoplasmic compartment composed of BiP/GRP78, GM130, and TGN46, indicating that gH was retained in the cytoplasmic compartment with ER and Golgi markers.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of cellular compartment of gH induced by anti-gH-MAb treatment. Upper and lower panels show infected cells on day 2 without anti-gH-MAb and on day 5 with anti-gH-MAb treatment. The double staining of gH and cellular organelle markers BiP/GRP78 (ER), GM130 (cis-Golgi), and TGN46 (trans-Golgi) is shown. Anti-gH-MAb (clone 36) with red staining was used in combination with anti-BiP/GRP78 MAb, anti-GM130 MAb, and anti-TGN46 rabbit polyclonal antibody. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and FITC-labeled anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies to detect the cellular proteins and stained green. gH was distributed in the whole cytoplasm and colocalized with GM130 and TGN46 but not with Bip/GRP78 without anti-gH-MAb on day 2. gH, Bip/GRP78, GM130, and TGN46 were accumulated and colocalized in the cytoplasmic compartment near the nucleus with anti-gH-MAb on day 5.

The uncoordinated distributions of gE and gH indicated the loss of a coordinated formation of infectious virions or infectivity in the infected cell. Thus, anti-gH-MAb modulated the distribution of gH in the treated cells, and this rendered the infected cells noninfectious, even after the removal of anti-gH-MAb from the infectious center assay, as shown in Fig. 1.

Stable dormancy of VZV infectivity in quiescently infected cells.

VZV in cells treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks did not resume the replication of VZV for more than a week in the absence of anti-gH-MAb, as shown in Fig. 1. The quiescently infected cells were given various treatments on day 28 to restart the replication of VZV. The infected cells that had been treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks were cultured without anti-gH-MAb for 8 weeks further, but no plaques were observed even when fresh HEL cells were added. The superinfection of quiescently infected cells with human CMV, rhinovirus 13, or adenovirus 5 induced their respective cytopathologies in fresh HEL cell cultures but failed to rescue the VZV infectivity or expression of gH from the quiescent VZV. Superinfection with cell-free VZV heated at 41°C for an hour did not induce VZV cytopathology.

Quiescently infected cells were heated at 41°C for 1 h, treated with 5 mM N-butyrate, or treated with 100 ng/ml 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, but no plaque formation was detected in the culture. Each treatment was examined in at least three independent experiments using 8 to 10 wells of 12-well culture plates. Thus, VZV in the quiescently infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb was stably dormant against various treatments.

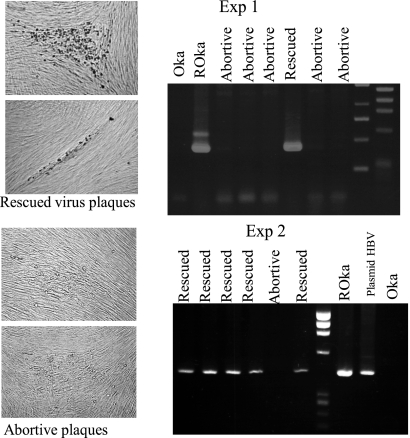

Rescue of ROka expressing HBsAg in quiescently infected cells by superinfection of OkaV.

ROka has two selection markers, acyclovir resistance due to TK deficiency and HBsAg expression, that are used to differentiate it from OkaV. HEL cells were inoculated with ROka and treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks to render them quiescently infected, and then the cells were superinfected with OkaV cell-free virus. The superinfected cells were cultured, and total virus stock was made to screen the TK-deficient virus in the presence of acyclovir. Infectious ROka with markers of TK deficiency and HBsAg was recovered in the presence of acyclovir from the quiescently infected cells by superinfection with OkaV (Fig. 4). The ratio of plaques formed by ROka to total plaques formed by ROka and OkaV in the absence of acyclovir in the cell-free virus was calculated in two successive experiments, as shown in Table 1. Table 1 shows the percentage of rescued ROka plaques among total plaque numbers deduced from the number of plaques formed without acyclovir in a dish. The plaques appearing in the dish treated with acyclovir were designated recovered ROka plaques and confirmed by the presence of the HBsAg gene by PCR as shown in Fig. 4. Some abortive plaques appeared in the presence of acyclovir, but these plaques did not develop further in a fresh culture with acyclovir. These abortive plaques were propagated in the absence of acyclovir, but PCR revealed them to be deficient in the HBsAg gene. HEL cells in 12-well plates were infected with ROka, and the numbers of plaques formed were 173 and 632 per well in experiments 2 and 3, respectively, in the infectious center assay. In these infection conditions with ROka, the ratios of recovered ROka per OkaV plaque in the cell-free virus preparation were 0.3 to 1.8% and 0.01 to 0.06% in experiments 2 and 3, respectively. The infectivity per VZV virus particle was 1:106 in our previous study (37), and the yields of cell-free virus varied in the preparations. Although it is difficult to calculate the exact efficiency of the rescue rate due to the difficulty in preparing cell-free VZV, the dormant ROka was recovered by superinfection with OkaV, indicating that the dormant VZV genome was infectious.

Fig. 4.

Confirmation of rescue of dormant ROka in quiescently infected cells by superinfection with OkaV. Rescued ROka was confirmed by the PCR amplification of 432 bp of the HBsAg gene in ACV-resistant plaques. The cells infected with TK-deficient ROka were treated with anti-gH-MAb, and the resultant quiescent cells were infected with OkaV, followed by the preparation of cell-free virus. The plaques produced by the quiescently ROka-infected cells were isolated in the presence of 10 μg/ml acyclovir and examined for the presence of the HBsAg gene by PCR. When abortive plaques were isolated and propagated in the absence of acyclovir, the HBsAg gene was not detected by PCR, indicating that the HBsAg gene was not contaminated by dormant ROka DNA. Rescued ROka grew well in the presence of acyclovir and possessed the HBsAg gene, confirming the replication of dormant ROka in the quiescently infected cells by superinfection with OkaV.

Table 1.

Recovery of quiescent ROka by superinfection with OkaVa

| Expt and well no. | No. (%) of ACV-resistant plaques isolated/total plaques |

|---|---|

| Expt 1 | |

| 1 | 0/95 (0) |

| 2 | 0/13,224 (0) |

| 3 | 3/9,120 (0.03) |

| 4 | 0/38 (0) |

| 5 | 0/19 (0) |

| 6 | 2/114 (1.80) |

| 7 | 0/19 (0) |

| 8 | 0/57 (0) |

| Expt 2 | |

| 1 | 3/10,355 (0.03) |

| 2 | 5/19,000 (0.03) |

| 3 | 6/11,457 (0.05) |

| 4 | 1/1,615 (0.06) |

| 5 | 2/6,802 (0.03) |

| 6 | 1/9,120 (0.01) |

| 7 | 1/5,795 (0.02) |

| 8 | 0/3,230 (0) |

| 9 | 0/9,196 (0) |

ROka was inoculated into HEL cells in 12-well plates, and the numbers of plaques formed by the infectious center assay were 250 and 177 per well in experiments 1 and 2, respectively. Cell-free virus preparation obtained from quiescently ROka-infected cells superinfected with OkaV was inoculated into up to 20 6-cm petri dishes depending on the amount of cell-free virus preparation. One dish was incubated without acyclovir, and the rest were incubated with 10 μg/ml acyclovir. The plaques appearing in the presence of acyclovir were designated rescued ROka plaques after the confirmation of the presence of the HBsAg gene by PCR, and the percentage was determined from the plaque number of ROka and OkaV formed in the dish without acyclovir in each well.

Analysis of VZV transcripts and products in quiescently infected cells.

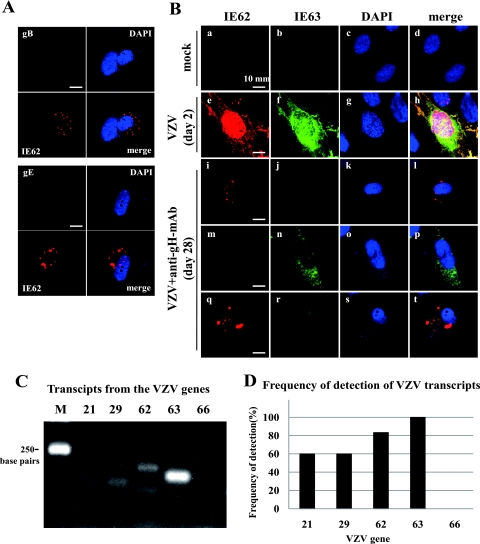

When the IFA using antibodies to gE, gB, IE62, and IE63 was performed on the quiescently infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks, staining with antibodies to IE62 and IE63 was observed. As shown in Fig. 5A, IE62 was visualized by anti-IE62 staining, but both gB and gE were undetectable in the same cells, indicating efficient downregulation glycoprotein expression by anti-gH-MAb. This indicated that at least IE62 was detectable in the quiescently infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb on day 28.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of expression of viral proteins and transcripts in quiescently infected cells. (A) Immunofluorescent staining for gB, gE, and IE62 in quiescently infected cells. HEL cells infected with the parent Oka strain were cultured for 4 weeks in the presence of anti-gH-MAb, followed by fixation and double staining for gB (green) or gE (green) with IE62 (red). The nucleus was labeled with DAPI (blue). (B) Expression of IE62 and IE63 in the quiescently infected cells. Mock-infected cells (a to d), VZV-infected cells without anti-gH-MAb treatment on day 2 (e to h), and the quiescently infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb for 4 weeks were stained with IE62 (red) or IE63 (green) and DAPI (blue) (i to t). (a to d) Mock-infected cells had no staining with IE62 and IE63. (e to h) Strong nuclear staining with IE62 and IE63 and cytoplasmic staining were observed, but the distribution pattern of IE62 and IE63 was similar and mostly colocalized in VZV-infected cells without anti-gH-MAb. (i to l and q to t) Freckled or dotted staining with anti-IE62 antibody was observed in the cytoplasm of fibroblasts. (m to p and q to t) Granular staining with anti-IE63 antibody was observed in the cytoplasm of the cell. (q to t) Both IE62 and IE63 were observed in the cytoplasm of round cells. The number of IE63-positive cells was more than that of IE62-positive cells, and double staining with anti-IE62 and anti-IE63 antibodies was observed in a limited number of cells. (C) Transcripts of the VZV genome in quiescently infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb. PCR products were not amplified from the extracted RNA of quiescently infected cells without cDNA synthesis. Transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 were amplified as described in the text, and the expected sizes of products were detected as shown in panel C. M indicates a molecular size of 250 bp. (D) Transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 in extracts from five or six independent cultures were examined, and the frequency of their detection is summarized in the graph.

Mock-infected cells had no staining with anti-IE62 and anti-IE63 antibodies (Fig. 5B, images a to d). IE62 and IE63 were strongly and predominantly expressed in the nucleus and the cytoplasm and were colocalized in the cytoplasmic region near the nucleus in the lytically infected cells on day 2 (Fig. 5B, images e to h). The expression of IE62 and IE63 was observed in the quiescent state on day 28 but was quite different from that of the lytically infected cells (Fig. 5B, images e and f). IE62 was detected as speckled or dotted forms with sharp margins in the cytoplasm, and IE63 distributed mainly in the cytoplasm in the granular form (Fig. 5B, images i to t). The cells expressing both IE62 and IE63 were round rather than typical fibroblast forms (Fig. 5B, images q to t). The cells stained doubly with IE62 and IE63 would be present in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 5B, image r). However, the exact localization should be examined by Z stack analysis. The cells expressing IE63 alone showed mainly granular cytoplasmic fluorescence in the cytoplasm in the repeated experiments as represented in Fig. 5B, image n. The cells expressing IE63 were observed twice as frequently as those expressing IE62, and the cells expressing both IE62 and IE63 were least in number. These results demonstrated that IE63 and IE62 were specifically expressed in quiescently infected cells.

We observed the presence of IE62 and IE63 in the quiescently infected cells by the IFA and assessed the transcription of the VZV gene during this quiescent state of infection. Various transcripts detected in latently infected human ganglia cells (4–7, 16, 20, 22) were examined in the quiescently infected cells by reverse transcription-PCR. When the RNA extracted from quiescently infected cells was treated with DNase, no PCR product was amplified without cDNA synthesis, indicating an absence of contaminating viral input DNA. After the synthesis of cDNA using an oligo(dT) primer, transcripts of the VZV genes were characterized. As shown in Fig. 5C and D, transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 were detected in the quiescently infected cells in five or six experiments, and among the four transcripts, transcripts from gene 63 were the most abundant. No transcript of gene 66 was detected. Transcripts of gene 63 were detected in every assay, and thus it was the most abundant and frequent transcript. This was consistent with the IFA observation that IE63 was most frequently detected in the quiescently infected cells.

DISCUSSION

The fate of infected cells treated with anti-gH-MAb was investigated in this study. Anti-gH-MAb neutralizes viral infectivity and inhibits cell-to-cell infection, preventing plaque formation. Anti-gH-MAb efficiently downregulates the intracellular viral antigen expression designated antigenic modulation (9, 25, 26). Two major results were obtained in this study. One was that the treatment of infected cells with anti-gH-MAb modified the intracellular localization of gH, eliminated viral infectivity, and modulated the VZV infectivity to stable dormancy. The gene regulation of the dormant VZV genome and the transcription and expression of IE62 and IE63 were similar to those observed in neurons of human ganglia latently infected with VZV. The other result was that the infectivity of the dormant VZV was recoverable from the quiescently infected cells by superinfection with VZV. These results indicate the similarity of the quiescently infected cells in vitro to human ganglia latently infected with VZV.

Although the antigenic modulation of viral pathogenesis has been extensively studied in measles virus-infected cells, the mechanism of viral gene regulation by an antibody to a surface antigen of infected cells has not been clarified. Vleck et al. reported that anti-gH-MAb 206 against VZV modified viral replication and spread in skin xenografts in the severe combined immunodeficient mouse model (47). Anti-gH antibody bound to plasma membranes and to surface virus particles, from which it was internalized into vacuoles within infected cells associated with intracellular virus particles and colocalized with markers for early endosomes and multivesicular bodies but not the trans-Golgi network (47). In contrast to their study of the incomplete inhibition of the spread of infection, which allowed the spread of infection, the anti-gH-MAb in our infection system completely inhibited the cell-to-cell spread of infection and restricted the infection to a single cell. The expression of gB and gE also was confined to a single cell and was not detected in infected cells before day 28 (Fig. 2 and 5). The localization of gH was modulated and confined to a cytoplasmic compartment composed of the ER marker (BiP/GRP78) and Golgi markers (GM130 and TGN48) near the nucleus. Anti-gH-MAb treatment caused the loss of the coordinated distribution of gH and gE on day 5 and ceased the glycoprotein expression on day 28. Thus, anti-gH-MAb modulated the intracellular distribution of gH and terminated the lytic infection by rendering the VZV genome dormant and the gene regulation from the dormant VZV similar to those observed in ganglionic cells latently infected with VZV. Thus, antigenic modulation by anti-gH-MAb may be as important in VZV pathogenesis as that observed in measles virus infection.

The mechanism of the modification of gene expression by anti-gH-MAbs is not clear, but infected cells were converted to noninfectious and apparently normal cells. The quiescently infected cells were stable in the presence of various stimuli, and only superinfection with VZV rescued the quiescent infectious VZV. Rescued ROka was selected from among the viruses produced after superinfection with OkaV, and its identity was confirmed by the two markers of TK deficiency and the HBsAg gene. We thought the inoculated ROka was rescued rather than being a recombination between OkaV and part of the ROka genome, because the frequency of recovery of ROka was relatively higher than that of isolating the recombinant virus by the transfection of plasmid DNA (32, 36). However, the possibility that a recombinant virus emerged containing the regions encoding TK deficiency and the HBsAg gene should be carefully excluded. The dormant VZV may have been activated by a viral regulatory unit of the superinfected virus rather than by cellular components, because the propagation of quiescent cells alone failed to initiate the replication of quiescent VZV. Although limited parts of the genome were transcribed, as shown in Fig. 5, the infectious genome did not restart replication in spite of various stimuli. Thus, the genome was stably dormant but actively transcribed and regulated in a sophisticated way.

The anti-gH-MAb used was clone 94, which had the highest neutralizing activity among the eight clones used in the previous study (1, 42), and the quiescently infected cells were produced by treatment with another neutralizing anti-gH-MAb (clone 24) with a epitope different from that of clone 94 (data not shown). Thus, the antigenic modulation of VZV-infected cells was dependent on the neutralizing anti-gH-MAb and was not an epitope-specific phenomenon.

A latency model of HSV in cell cultures in vitro was established by treatment with interferon and an antiviral compound, followed by temperature elevation to 41°C, after which the latent HSV was reactivated by superinfection with CMV (35, 49, 50). However, in spite of the similarity to the quiescent status of HSV-infected cells, CMV failed to recover the infectivity of VZV, indicating a difference between HSV and VZV in the status of genome regulation in quiescently infected cells.

Transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 have been identified in human ganglia (4–7, 16, 20, 22), and gene 63 transcripts are the most abundant of those detected during latency. IE63 is expressed predominantly in the cytoplasm in sensory neurons, in contrast to the predominantly nuclear distribution in lytically infected cells (20, 21). We examined transcripts and viral antigens in the quiescently infected cells to compare the transcription and expression of VZV antigens to those of latently infected ganglia. Transcripts from genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 were detected, and the expression of IE62 and IE63 was observed in the cytoplasm of the quiescently infected cells. IE63 transcript and product were detected mostly in the quiescently infected cells. Transcripts from the TK gene were not detected, as the lytic-phase gene (data not shown) was similar to that from gene 66. Thus, the gene regulation of dormant VZV and the presence of the infectious genome in the quiescently infected cells were similar to the gene regulation of VZV in latently infected human ganglia.

The antigenic modulation by anti-gH-MAb observed in this study indicates that VZV in infected cells becomes dormant, possibly due to the modification of the intracellular localization of gH, and the gene regulation is similar to that observed in neurons of human sensory ganglia. The similarity in the gene regulation of the quiescently infected cells to that of neurons in human sensory ganglia reflects the biological importance of this modification of gene regulation by an antibody in the pathogenesis of VZV infection, and it indicates that this system is a suitable model in vitro to analyze the gene regulation of latent VZV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Katherine Ono for editing the manuscript.

This study was supported in part by a grant for Research Promotion of Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases (H18-Shinko-013) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and Grants in Aid (135508094, 22600003, and 22790428) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

We have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akahori Y., et al. 2009. Characterization of neutralizing epitopes of varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein H. J. Virol. 83:2020–2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beers S. A., et al. 2010. Antigenic modulation limits the efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies: implications for antibody selection. Blood 115:5191–5201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beum P. V., Mack D. A., Pawluczkowycz A. W., Lindorfer M. A., Taylor R. P. 2008. Binding of rituximab, trastuzumab, cetuximab, or mAb T101 to cancer cells promotes trogocytosis mediated by THP-1 cells and monocytes. J. Immunol. 181:8120–8132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohrs R. J., Barbour M. B., Mahalingam R., Wellish M., Gilden D. H. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: prevalence of VZV gene 21 transcripts in latently infected human ganglia. J. Virol. 69:2674–2678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohrs R. J., Gilden D. H. 2007. Prevalence and abundance of latently transcribed varicella-zoster virus genes in human ganglia. J. Virol. 81:2950–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohrs R. J., Gilden D. H., Kinchington P. R., Grinfeld E., Kennedy P. G. 2003. Varicella-zoster virus gene 66 transcription and translation in latently infected human Ganglia. J. Virol. 77:6660–6665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohrs R. J., et al. 2000. Analysis of individual human trigeminal ganglia for latent herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acids using real-time PCR. J. Virol. 74:11464–11471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daikoku T., et al. 2005. Architecture of replication compartments formed during Epstein-Barr virus lytic replication. J. Virol. 79:3409–3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujinami R. S., Norrby E., Oldstone M. B. 1984. Antigenic modulation induced by monoclonal antibodies: antibodies to measles virus hemagglutinin alters expression of other viral polypeptides in infected cells. J. Immunol. 132:2618–2621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fujinami R. S., Oldstone M. B. 1980. Alterations in expression of measles virus polypeptides by antibody: molecular events in antibody-induced antigenic modulation. J. Immunol. 125:78–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujinami R. S., Oldstone M. B. 1979. Antiviral antibody reacting on the plasma membrane alters measles virus expression inside the cell. Nature 279:529–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hama Y., et al. 2010. Antibody to varicella-zoster virus immediate-early protein 62 augments allodynia in zoster via brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Virol. 84:1616–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Imakita M., Shiraki K., Yutani C., Ishibashi-Ueda H. 2000. Pneumonia caused by rhinovirus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:611–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joseph B. S., Oldstone M. B. 1975. Immunologic injury in measles virus infection. II. Suppression of immune injury through antigenic modulation. J. Exp. Med. 142:864–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamiyama T., Sato H., Takahara T., Kageyama S., Shiraki K. 2000. Novel immunogenicity of Oka varicella vaccine vector expressing hepatitis B surface antigen. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1158–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kennedy P. G., Grinfeld E., Bell J. E. 2000. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected and explanted human ganglia. J. Virol. 74:11893–11898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennedy P. G., Grinfeld E., Gow J. W. 1999. Latent varicella-zoster virus in human dorsal root ganglia. Virology 258:451–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuramoto T., et al. 2010. Novel anti-cytomegalovirus activity of immunosuppressant mizoribine and its synergism with ganciclovir. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333:816–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kurosaki K., et al. 2004. Therapeutic basis of vidarabine on adenovirus-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 15:281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lungu O., Panagiotidis C. A., Annunziato P. W., Gershon A. A., Silverstein S. J. 1998. Aberrant intracellular localization of Varicella-Zoster virus regulatory proteins during latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:7080–7085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mahalingam R., et al. 1996. Expression of protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 in latently infected human ganglionic neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:2122–2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meier J. L., Holman R. P., Croen K. D., Smialek J. E., Straus S. E. 1993. Varicella-zoster virus transcription in human trigeminal ganglia. Virology 193:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okuda T., et al. 2004. Suppression of generation and replication of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus by a sensitive virus. J. Med. Virol. 72:112–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okuno T., Yamanishi K., Shiraki K., Takahashi M. 1983. Synthesis and processing of glycoproteins of Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) as studied with monoclonal antibodies to VZV antigens. Virology 129:357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Old L. J., Stockert E., Boyse E. A., Kim J. H. 1968. Antigenic modulation. Loss of TL antigen from cells exposed to TL antibody. Study of the phenomenon in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 127:523–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oldstone M. B., Welsh R. M., Joseph B. S. 1975. Pathogenic mechanisms of tissue injury in persistent viral infections. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 256:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ono Y., et al. 1983. The complete nucleotide sequences of the cloned hepatitis B virus DNA; subtype adr and adw. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1747–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oshima K., et al. 2008. Case report: persistent cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using in vivo alemtuzumab: emergence of resistant CMV due to mutations in the UL97 and UL54 genes. J. Med. Virol. 80:1769–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perng G. C., Jones C. 2010. Towards an understanding of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-reactivation cycle. Interdisc. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2010:262415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pulczynski S. 1994. Antibody-induced modulation and intracellular transport of CD10 and CD19 antigens in human malignant B cells. Leuk. Lymphoma. 15:243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pulczynski S., Boesen A. M., Jensen O. M. 1994. Modulation and intracellular transport of CD20 and CD21 antigens induced by B1 and B2 monoclonal antibodies in RAJI and JOK-1 cells–an immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy study. Leuk. Res. 18:541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shiraki K., et al. 1991. Development of immunogenic recombinant Oka varicella vaccine expressing hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1393–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiraki K., et al. 1992. Processing of hepatitis B virus surface antigen expressed by recombinant Oka varicella vaccine virus. J. Gen. Virol. 73:1401–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shiraki K., et al. 1992. Comparison of antiviral assay methods using cell-free and cell-associated varicella-zoster virus. Antiviral Res. 18:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shiraki K., Rapp F. 1986. Establishment of herpes simplex virus latency in vitro with cycloheximide. J. Gen. Virol. 67:2497–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shiraki K., et al. 2001. Construction of Oka varicella vaccine expressing human immunodeficiency virus env antigen. J. Med. Virol. 64:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shiraki K., Takahashi M. 1982. Virus particles and glycoprotein excreted from cultured cells infected with varicella-zoster virus (VZV). J. Gen. Virol. 61:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shiraki K., Yoshida Y., Asano Y., Yamanishi K., Takahashi M. 2003. Pathogenetic tropism of varicella-zoster virus to primary human hepatocytes and attenuating tropism of Oka varicella vaccine strain to neonatal dermal fibroblasts. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1875–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Southgate T. D., et al. 2010. CXCR4 mediated chemotaxis is regulated by 5T4 oncofetal glycoprotein in mouse embryonic cells. PLoS One 5:e9982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stevens J. G. 1990. Transcripts associated with herpes simplex virus latency. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 278:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sugano T., et al. 1991. A human monoclonal antibody against varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein III. J. Gen. Virol. 72:2065–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Suzuki K., Akahori Y., Asano Y., Kurosawa Y., Shiraki K. 2007. Isolation of therapeutic human monoclonal antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and the effect of light chains on the neutralizing activity. J. Med. Virol. 79:852–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takemoto M., Imasawa T., Yamanishi K., Mori Y. 2009. Role of dendritic cells infected with human herpesvirus 6 in virus transmission to CD4(+) T cells. Virology 385:294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takemoto M., et al. 2005. Human herpesvirus 6 open reading frame U14 protein and cellular p53 interact with each other and are contained in the virion. J. Virol. 79:13037–13046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Taylor R. P., Lindorfer M. A. 2010. Antigenic modulation and rituximab resistance. Semin. Hematol. 47:124–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toyama N., Shiraki K. 2009. Epidemiology of herpes zoster and its relationship to varicella in Japan: A 10-year survey of 48,388 herpes zoster cases in Miyazaki prefecture. J. Med. Virol. 81:2053–2058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vleck S. E., et al. 2010. Anti-glycoprotein H antibody impairs the pathogenicity of varicella-zoster virus in skin xenografts in the SCID mouse model. J. Virol. 84:141–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wakkach A., et al. 1999. Establishment of a human thymic myoid cell line. Phenotypic and functional characteristics. Am. J. Pathol. 155:1229–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wigdahl B. L., Isom H. C., Rapp F. 1981. Repression and activation of the genome of herpes simplex viruses in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:6522–6526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wigdahl B. L., Scheck A. C., De Clercq E., Rapp F. 1982. High efficiency latency and activation of herpes simplex virus in human cells. Science 217:1145–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zerboni L., et al. 2010. Expression of varicella-zoster virus immediate-early regulatory protein IE63 in neurons of latently infected human sensory ganglia. J. Virol. 84:3421–3430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zimring J. C., Cadwell C. M., Spitalnik S. L. 2009. Antigen loss from antibody-coated red blood cells. Transfus. Med. Rev. 23:189–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]