Abstract

Background

Evidence from the United States and Europe suggests that the use of prescription drugs may vary by ethnicity. In Canada, ethnic disparities in prescription drug use have not been as well documented as disparities in the use of medical and hospital care. We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of survey and administrative data to examine needs-adjusted rates of prescription drug use by people of different ethnic groups.

Methods

For 19 370 non-Aboriginal people living in urban areas of British Columbia, we linked data on self-identified ethnicity from the Canadian Community Health Survey with administrative data describing all filled prescriptions and use of medical services in 2005. We used sex-stratified multivariable logistic regression analysis to measure differences in the likelihood of filling prescriptions by drug class (antihypertensives, oral antibiotics, antidepressants, statins, respiratory drugs and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). Models were adjusted for age, general health status, treatment-specific health status, socio-economic factors and recent immigration (within 10 years).

Results

We found evidence of significant needs-adjusted variation in prescription drug use by ethnicity. Compared with women and men who identified themselves as white, those who were South Asian or of mixed ethnicity were almost as likely to fill prescriptions for most types of medicines studied; moreover, South Asian men were more likely than white men to fill prescriptions for antibiotics and NSAIDs. The clearest pattern of use emerged among Chinese participants: Chinese women were significantly less likely to fill prescriptions for antihypertensives, antibiotics, antidepressants and respiratory drugs, and Chinese men for antidepressant drugs and statins.

Interpretation

We found some disparities in prescription drug use in the study population according to ethnic group. The nature of some of these variations suggest that ethnic differences in beliefs about pharmaceuticals may generate differences in prescription drug use; other variations suggest that there may be clinically important disparities in treatment use.

From 1986 to 2006, as a result of their increased availability, promotion and use, prescription drugs became the fastest growing component of Canada’s health care costs.1 During that time, the ethnic composition of Canada’s population changed substantially: the share of the population born outside Canada rose from 16% to 20%, and the share belonging to “visible minorities” increased from 6% to 16%.2 Although ethnicity is a difficult construct to work with empirically, it an important marker of societal groupings for health care practice and policy. People of different ethnic identities may have different needs for, access to and even outcomes from health care.3 Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medical and hospital care have been documented in Canada and other developed countries;4-8 however, disparities in prescription drug use have not been studied as thoroughly in Canada. Evidence from the United States and Europe suggests that prescription drug use may vary by race and country of birth, and Canadian studies have shown disparities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations.9-14

With regard to the growing non-Aboriginal ethnic minority groups in Canada, it may not be possible, for a number of reasons, to extrapolate existing evidence of disparities in the use of health services to disparities in the use of prescription drugs. Because outpatient pharmaceutical benefits are not universal in Canada, disparities in access to prescription drugs may exist even if access to primary care is relatively equitable. Moreover, ethnic differences in beliefs about pharmaceuticals could result in differences in the use of medicines that are not reflected in the use of other health services.15

We compared the use of prescription drugs in a sample of residents of different ethnic backgrounds in the province of British Columbia. We studied the use of prescription drugs from 6 therapeutic classes: antihypertensives, oral antibiotics, antidepressants, statins, respiratory drugs and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). We chose these classes to reflect commonly used medicines (which was necessary to ensure sufficient statistical power in the analysis) that spanned a variety of therapeutic purposes. The latter criterion enabled us to explore the hypothesis that, owing to the influences of personal beliefs, ethnic variations in the use of prescription drugs will differ by the nature of treatment.

Methods

Data source

We obtained data from the 2001, 2003 and 2005 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Conducted in English, French or the interviewee’s preferred language, the CCHS is completed by a randomly selected person aged 12 or older per household drawn from a complex sample frame.16 For our study, we included data from respondents in British Columbia whose CCHS data could be linked to administrative health care datasets maintained by Population Data BC. The administrative datasets do not include data from registered First Nations, veterans, inmates of federal penitentiaries and Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

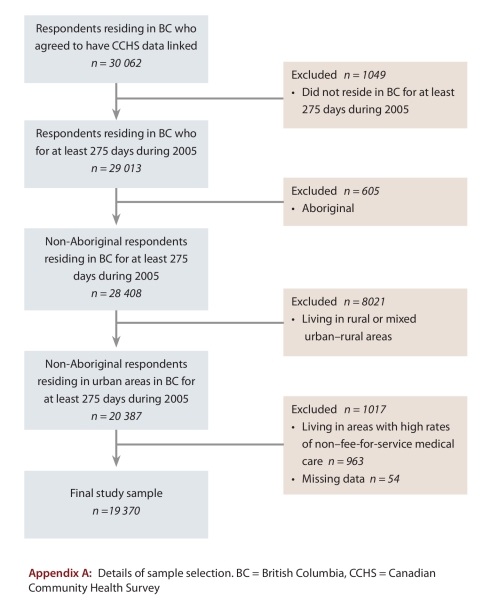

We excluded CCHS respondents in rural and mixed urban-rural areas, because ethnic minority groups are highly concentrated in urban settings and because there are marked urban/rural differences in the use of prescription drugs in British Columbia.17 The addition of rural populations (with appropriate controls for rural settings) would have increased only the sample size without adding statistical power. We excluded CCHS respondents who identified themselves as Aboriginal because their administrative health care data may have been incomplete and therefore may have biased results. To ensure comparability of data, we also excluded individuals with missing CCHS data, those who did not reside in British Columbia for at least 275 days in 2005 and those who lived in areas with high rates of non–fee-for-service medical care. The last exclusion criterion was necessary because our measures of health status were based in part on diagnoses from fee-for-service medical claims data; high rates of non–fee-for-service care would bias these measures. (See Appendix A for details regarding the sample selection.)

Study variables

Using the BC PharmaNet database, we identified all prescriptions filled by study participants during 2005. PharmaNet records every prescription dispensed in community pharmacies and long-term care facilities, regardless of patient age or insurance status. Our primary outcome was whether an individual filled one or more prescriptions during 2005 for an antihypertensive, an oral antibiotic, an antidepressant, a statin, a respiratory drug or an NSAID. (See Appendix B for details regarding therapeutic categories.)

Our ethnicity measure was based on responses to the CCHS question “People living in Canada come from many different cultural and racial backgrounds. Are you: ...?” Individuals could respond yes to any of 13 ethnic groups read to them. We coded individuals who responded yes to more than one ethnic group as being of mixed ethnicity; those who responded yes to a single ethnic group were assigned to one of the following categories: white; Chinese; South Asian; other Asian; or non-Asian, non-white. (See Appendix C for details regarding ethnic groupings.) We also used the CCHS data to identify recent immigrants, whom we defined as respondents who immigrated to Canada within 10 years of 2005 (our observation year).

To measure health status, we constructed aggregated diagnostic groups (ADGs) and expanded diagnostic clusters (EDCs) based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10) codes drawn from records of all fee-for-services medical visits and hospital discharges during 2005.18 A higher count of ADGs indicates a greater degree of overall clinical complexity and is predictive of increased likelihood of prescription drug use.19 EDCs denote the diagnosis of specific clinical conditions; we used EDCs to identify common indications for each of the drug classes studied (see Appendix B). The EDCs included in each model were selected by practising physicians and a clinical pharmacist for a previously published study of prescription drug use in British Columbia.17

We used administrative records to construct household income quintiles based on a combination of household-specific and neighbourhood-level income data.20 Evidence indicates that access to public drug benefits does not differ by ethnic group.21 However, to adjust for possible differences in access to private insurance benefits, we identified all individuals living in households for which the family’s provincial medical premiums were paid through a household member’s employment. Such payment is an indicator of employment-related health benefits that often also include private drug coverage.

Statistical analysis

We computed unweighted, sex-stratified multivariable logistic regressions on our outcome variables. Informed by models of health services utilization and evidence concerning prediction of pharmaceutical use and costs, our models included age, health status, income, employment-related health benefits and recent immigration (within 10 years). To allow for nonlinear relationships between age and the likelihood of filling prescriptions, we defined age using dummy variables for 10-year age groups. Findings concerning ethnic variations were robust to the inclusion or exclusion of variables that were not consistently statistically significant, namely employment-related health benefits and recent immigration.

Funding and ethics approval

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The construction of the research database was supported in part by contributions of the British Columbia Ministry of Health Services to the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia. The sponsors had no role in the project or in decisions to publish the results. The de-identified data were provided by Population Data BC with permission of data stewards at the British Columbia Ministry of Health Services and with permission ofthe College of Pharmacists of British Columbia. The study protocol was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

Results

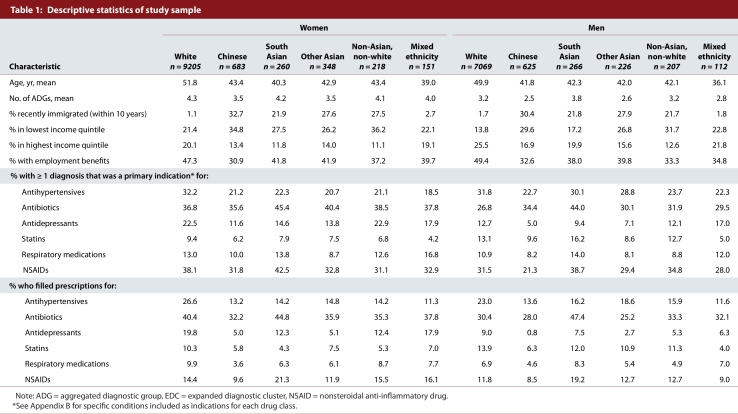

The final sample for our study included 19 370 individuals (Table 1). People who identified themselves as white were older, wealthier, less healthy and less likely to have recently immigrated to Canada than people who were of non-white ethnic backgrounds. Respondents of mixed ethnicity (85% of whom replied yes to “white” and a visible minority group) were younger, wealthier and less likely to be a recent immigrant than those of a single ethnic group.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study sample

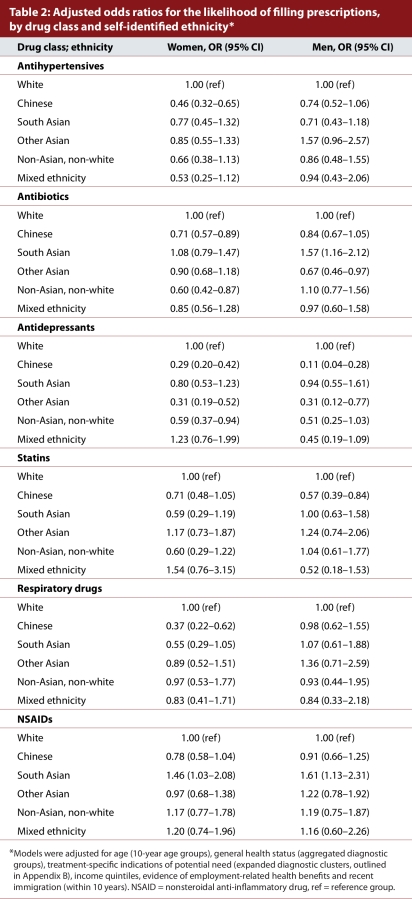

Crude rates of diagnoses of conditions for which the selected drug classes are indicated varied by ethnic group, the largest variation being observed for diagnoses for which antidepressants are indicated. White women, white men and south Asian men had the highest sex-specific prevalence of conditions for which antihypertensives are commonly indicated. South Asian men had the highest prevalence of conditions for which antibiotics, statins, NSAIDs and respiratory drugs are commonly indicated. South Asian women had the highest prevalence of conditions for which antibiotics and NSAIDs are commonly indicated. Women who were in either the white or the non-Asian, non-white ethnic groups and men of mixed ethnicity had the highest prevalence of conditions for which antidepressants are commonly indicated. Crude rates of antihypertensive, antidepressant and statin use were highest among white women and men; crude rates of antibiotic and NSAID use were highest among South Asian women and men. Crude rates of respiratory drug use were highest among white women and South Asian men. After adjustment for age, general health status (using counts of ADGs), condition-specific indications (using specific EDCs), socio-economic factors and recent immigration, several ethnic differences in the use of prescription drugs remained. Table 2 lists adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the likelihood of filling prescriptions for antihypertensives, antibiotics, antidepressants, statins, respiratory drugs and NSAIDS by ethnic group. For antihypertensive prescriptions, Chinese women were about half as likely as white women to fill them (OR 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.32–0.65). Chinese men were less likely than white men to fill antihypertensive prescriptions, although the difference was not significant (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.52–1.06). None of the other ethnic differences in the odds of filling prescriptions for antihypertensives were statistically significant. Chinese women and non-Asian, non-white women had significantly lower odds of filling prescriptions for antibiotics than white women. South Asian men were significantly more likely than white men to fill antibiotic prescriptions (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.16–2.12), while men of “other Asian” background were less likely to fill them (OR 0.67, CI 0.46–0.97). For antidepressant prescriptions, several ethnic groups (most significantly Chinese women and men, but also other Asian women and men, and non-Asian, non-white women) were significantly less likely than white women and men to fill them.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for the likelihood of filling prescriptions, by drug class and self-identified ethnicity

Table 2 lists adjusted odds ratios for the likelihood of filling prescriptions for statins, respiratory drugs and NSAIDs by ethnic group. Chinese women were significantly less likely than white women to fill prescriptions for respiratory medicines (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.22–0.62). For NSAID prescriptions, South Asian women and men were more likely than white women and men to fill them (women: OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.03–2.08; men: OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.13–2.31).

Interpretation

Using linked survey and administrative data, we found statistically significant ethnic differences in the use of prescription drugs among non-Aboriginal residents in urban areas of British Columbia, even after adjusting for age, health status, socio-economic factors and recent immigration. Compared with respondents who were white, those who were South Asian or of mixed ethnicity were about as likely to fill prescriptions for most classes of medicines studied; however, South Asian men were significantly more likely to fill prescriptions for antibiotics and NSAIDs. Although a dominant pattern is difficult to determine because ethnic differences in presciption drug use appear to vary across therapeutic categories, there are nevertheless some important disparities. Chinese women were less likely than white women to fill prescriptions for antihypertensives, antibiotics, antidepressants and respiratory drugs. Chinese men were less likely than white men to fill prescriptions for statins and antidepressants. Overall, ethnic disparities were greater among women than among men, which suggests that gender roles, relationships and institutions may modify the effects of ethnicity on patient or provider behaviour.

Although rates of prescription drug use are lower in British Columbia than in other provinces,22 we believe that the ethnic differences identified in our study are likely representative of disparities among ethnic populations in urban areas across Canada. Moreover, the results of our study are generally consistent with previous research from the United States and Europe, which showed that ethnic groups use prescription drugs less frequently than white people.9-12 Two findings from our study stand out from the literature on prescription drug use: the increased use of antibiotics by South Asian men compared with white men and the increased use of NSAIDs by South Asian woman and men compared with white women and men. However, there is evidence of a higher prevalence of reported pain among South Asian groups than among white people, which may explain these patterns.23

Differences in the use of prescription drugs across ethnic groups may have resulted from differences in access to medical care,4-8 burdens of illness,24-25 beliefs about medicines15 or communications with practitioners.26 The pattern of findings across the drug classes we studied suggests that some differences may stem from beliefs and preferences about the use of prescription drugs versus other treatment options (including herbal medicines).27 We found the greatest degree of ethnic variation in the use of antidepressants, a drug class for which cultural beliefs about health and treatment are likely to affect patient choices.15 Patients of different ethnic backgrounds who have depression or anxiety may present differently; immigrants to Canada may also choose to seek care through other sources, including importing medicines during visits to their country of birth.28 It is potentially encouraging that differences in the use of antihypertensives and statins were smaller than differences in the use of other classes of drugs; nevertheless, there appear to be ethnic differences of potential clinical significance in such essential drug classes, particularly for Chinese people. The source of such differences may not be limited to patient preference: a telephone survey of residents in Vancouver (the largest urban area of British Columbia) found that Chinese immigrants to Canada were less likely than people of other ethnic backgrounds to receive patient education about heart disease from their health care providers.26

Our study has limitations. Although we were able to link data on self-reported ethnic identities with administrative data on filled prescriptions, quantitative analysis of observational data can provide only a generalized account of the complex personal and social dimensions of ethnicity.29 Our measure of prescription drug use was based on filled prescriptions, with no guarantee that the medicines were actually taken. Moreover, some prescriptions may not be filled by patients owing to cost, beliefs or other reasons. Some of the ethnic differences in the use of prescription drugs in our study may therefore have been due to differences in the rates of prescriptions filled by patients, not to differences in the rates of prescriptions written by practitioners.

The use of administrative data also limits diagnostic information to that documented during encounters for medical and hospital services. Our methods may therefore understate the level of health care needs for groups who experience economic, cultural or other demonstrable barriers to health care. Given that our primary finding was that the use of prescription drugs was lower among ethnic minorities who may use fewer health services, the bias from underreporting health care needs would tend to understate the extent of needs-adjusted ethnic disparities.

Having pooled CCHS data across multiple years, we were unable to use information on self-reported health status and health care use from the survey, because such measures are not time-invariant. We were, however, able to link data on self-reported ethnicity to administrative health care data that are not subject to recall or social-desirability bias that might otherwise affect measurement of health care needs and prescription drug use. The linkage of 3 cycles of the CCHS data to administrative records produced a sample that, despite having a higher percentage of ethnic minorities than samples of the CCHS used in other studies,8 underrepresents immigrants and non-white ethnic groups in British Columbia compared with census data.2 A larger, linkable source of ethnicity data might have reduced confidence intervals around point estimates and thereby resulted in statistical significance of ethnic variations that appeared clinically important but not statistically significant in the present study (e.g., use of antihypertensives and statins by South Asian people).

Conclusion

Despite a relatively equitable system of health care financing in Canada, there appear to be significant ethnic differences in prescription drug use. Some of these differences, such as marked variation in the use of antidepressants, may reflect acceptable differences resulting from patient preferences and beliefs; others may reflect unacceptable inequities in quality of care and resulting outcomes. Further research is needed to separate the former from the latter. The differences in patterns of prescription drug use that we observed across ethnic groups suggest that simple comparisons between white people and a single “visible minority” group should be avoided whenever possible in future research. Moreover, our sex-specific findings suggest that gender and ethnicity interact in ways that are potentially important for health care practice and policy. To address these important issues with quality scientific evidence, more routine collection of, and research into, information concerning ethnicity and health care in Canada will be required.

Biographies

Steve Morgan, PhD, is associate professor at the School of Population and Public Health and associate director of the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, and lead of the Pharmaceutical Policy Research Collaboration.

Gillian Hanley, MA, is a doctoral candidate at the School of Population and Public Health and a graduate research assistant at the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia.

Colleen Cunningham, MA, is a research coordinator at the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia.

Hude Quan, MD, PhD, is an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Population Health Investigator and an associate professor at the Department of Community Health Sciences and the Centre for Health and Policy Study, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Details of sample selection

Appendix B.

Drug types and diagnoses included, by therapeutic categories studied

Appendix C.

Ethnic groups derived from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) data

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: This study was funded by an operating grant (“Equity in pharmacare: the effects of ethnicity and policy in British Columbia”) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The construction of the research database was supported in part by contributions of the British Columbia Ministry of Health Services to the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia. The sponsors had no role in the project or in decisions to publish the results.

Contributors: Steve Morgan conceived of the project and contributed to the design and acquisition of data; he oversaw the data analysis, contributed to the interpretation of results and was the principal author of the manuscript. Gillian Hanley contributed to the project conception and design and the acquisition of data; she conducted the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of results and all phases of writing the manuscript. Colleen Cunningham helped implement the study and contributed to the analysis of data, the interpretation of results and the revision of the manuscript. Hude Quan contributed to the project conception and design, the interpretation of results and the revision of the manuscript. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Steve Morgan is the study guarantor.

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2009. Ottawa: The Institute; 2009. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/National_health_expenditure_trends_1975_to_2009_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada's ethnocultural mosaic, 2006 census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2008. http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-562/index-eng.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhopal Raj. Revisiting race/ethnicity as a variable in health research. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):156–157. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.156-a. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/11818274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sproston K A, Pitson L B, Walker E. The use of primary care services by the Chinese population living in England: examining inequalities. Ethn Health. 2001;6(3-4):189–196. doi: 10.1080/13557850120078116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayberry R M, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57 Suppl 1:108–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiscella Kevin, Franks Peter, Doescher Mark P, Saver Barry G. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care 2002. 2002;40(1):52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu Stella M, Huang Zhihuan J, Singh Gopal K. Health status and health services utilization among US Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, and other Asian/Pacific Islander Children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):101–107. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quan Hude, Fong Andrew, De Coster Carolyn, Wang Jianli, Musto Richard, Noseworthy Tom W, Ghali William A. Variation in health services utilization among ethnic populations. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):787–791. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050674. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/16534085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominick Kelli L, Bosworth Hayden B, Jeffreys Amy S, Grambow Steven C, Oddone Eugene Z, Horner Ronnie D. Racial/ethnic variations in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use among patients with osteoarthritis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(10):683–694. doi: 10.1002/pds.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn B A. Children's health: racial and ethnic differences in the use of prescription medications. Am Acad Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):727–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Junling, Noel Jason M, Zuckerman Ilene H, Miller Nancy A, Shaya Fadia T, Mullins C D. Disparities in access to essential new prescription drugs between non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanic whites. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(6):742–763. doi: 10.1177/1077558706293638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringbäck Weitoft G, Ericsson O, Löfroth E, Rosén M. Equal access to treatment? Population-based follow-up of drugs dispensed to patients after acute myocardial infarction in Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Jan 6;64(4):417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0425-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson J F, McEwan K L. Utilization of common analgesic and anxiolytic medications by registered first nations residents of western Canada. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(4):601–616. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood Evan, Kerr Thomas, Palepu Anita, Zhang Ruth, Strathdee Steffanie A, Tyndall Mark W, Montaner Julio S G, Hogg Robert S. Slower uptake of HIV antiretroviral therapy among Aboriginal injection drug users. J Infect. 2006;52(4):233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horne Robert, Graupner Lída, Frost Susie, Weinman John, Wright Siobhan M, Hankins Matthew. Medicine in a multi-cultural society: the effect of cultural background on beliefs about medications. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(6):1307–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.009. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=15210101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Béland Yves. Canadian community health survey--methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13(3):9–14. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/studies-etudes/82-003/archive/2002/6099-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan S, Cunningham C, Hanley G, Mooney D. The BC Rx Atlas. 2nd edition. Vancouver: Centre for Health Services and Policy Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner J P, Starfield B H, Steinwachs D M, Mumford L M. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452–472. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199105000-00006. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=1902278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley Gillian E, Morgan Steve, Reid Robert J. Explaining prescription drug use and expenditures using the adjusted clinical groups case-mix system in the population of British Columbia, Canada. Med Care. 2010;48(5):402–408. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca3d5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanley G, Morgan S. On the validity of area-based income measures to proxy household income. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-79. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/8/79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leong V, Morgan Steve, Wong S, Hanley Gillian, Black C. Registration for public drug benefits across areas of differing ethnic composition in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Health Services Res. 2010;10(1):171. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-171. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/20565754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan Steve, Raymond C, Mooney D, Martin D. The Canadian Rx Atlas. 2nd edition. Vancouver: Centre for Health Services and Policy Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer B, Macfarlane G, Afzal C, Esmail A, Silman A, Lunt M. Acculturation and the prevalence of pain amongst South Asian minority ethnic groups in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007 Mar 31;46(6):1009–1014. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu Maria, Austin Peter C, Manuel Douglas G, Tu Jack V. Comparison of cardiovascular risk profiles among ethnic groups using population health surveys between 1996 and 2007. CMAJ. 2010 Apr 19;182(8):301–310. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091676. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/20403888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creatore Maria I, Moineddin Rahim, Booth Gillian, Manuel Doug H, DesMeules Marie, McDermott Sarah, Glazier Richard H. Age- and sex-related prevalence of diabetes mellitus among immigrants to Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2010 Apr 19;182(8):781–789. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091551. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/20403889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grunau Gilat L, Ratner Pamela A, Galdas Paul M, Hossain Shahadut. Ethnic and gender differences in patient education about heart disease risk and prevention. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.026. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0738399109000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quan Hude, Lai Daniel, Johnson Delaine, Verhoef Marja, Musto Richard. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Chinese and white Canadians. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(11):1563–1569. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/19005129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall E, Wong S, Haggerty J, Levesque J F. Perceptions of unmet healthcare needs: What do Punjabi and Chinese-speaking immigrants think? A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Res. 2010;10(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-46. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/20175909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhopal Raj. Race and ethnicity: responsible use from epidemiological and public health perspectives. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(3):500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2006.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]