Abstract

Sexually coercive experiences, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems occur at relatively high base rates in college populations. As suggested by the self-medication hypothesis, alcohol consumption may be a means by which one can reduce negative affect or stress related to experiences of sexual coercion. However, few studies have directly tested the hypothesis that coping motives for drinking mediate the relation between sexual assault and problem drinking behaviors, and no published studies have tested this in men. The current study tested this hypothesis using structural equation modeling in a sample of 780 male and female undergraduates. Results revealed that coping motives partially mediated the relation between sexual coercion and drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences. In addition, direct and indirect paths between sexual coercion and drinking were found for men whereas only indirect paths were found for women. Results provide support for self-medication models of drinking and suggest the importance of exploring gender differences in mechanisms for drinking.

Keywords: Sexual coercion, drinking to cope, alcohol, consequences

1. Introduction

Problematic drinking has been linked to various negative consequences in college populations, including unwanted sexual experiences (Ham & Hope, 2003; Larimer, Lydum, Anderson, & Turner, 1999; Perkins, 2002). Previous research has found that alcohol use increased risk for sexual victimization experiences (Kaysen, Neighbors, Martell, Fossos, & Larimer, 2006; Testa & Parks, 1996; Ullman, 2003; Ullman, Karabatsos, & Koss, 1999) and that drinking increased in response to sexual victimization (Corbin, Bernat, Calhoun, McNair, & Seals, 2001; Hill, Schroeder, Bradley, Kaplan, & Angel, 2009; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2006). However, few studies have specifically examined the mechanisms of the relationship between victimization and problematic drinking (for exceptions, see Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Kaysen et al., 2007; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005), and have not generally focused on the impact of sexually coercive experiences per se on drinking behavior as opposed to sexual assault or rape. In addition, although sexually coercive experiences and responses to those experiences have been extensively studied in women (e.g., Blythe, Fortenberry, Temkit, Tu, & Orr, 2006; De Visser, Rissel, Richters, & Smith, 2007; Livingston, Buddie, Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, 2004; Zweig, Crockett, Sayer, & Vicary, 1999), there are few studies that investigated men or tested for gender differences in responses to sexual coercion (Larimer et al., 1999; O'Sullivan, Byers, & Finkelman, 1998; Zweig, Barber, & Eccles, 1997). The present research examined the extent to which using alcohol as a coping mechanism mediates the relation between sexual coercion and alcohol use and related consequences among college students. We further investigated whether this relation operated similarly for men and women.

1.2. Sexual coercion among college students

Sexual coercion refers to “behaviors in which nonphysical tactics (e.g., verbal pressure, lying, deceit, and continual arguments) are utilized to obtain sexual contact with an unwilling [partner]” (DeGue & DiLillo, 2005). As discussed by DeGue and DiLillo (2005), the term, “sexual coercion” has been used inconsistently and has been applied to sexual experiences that range considerably in severity. For example, sexual coercion has also been used to describe more subtle forms of pressure including intoxication or emotional manipulation (Basile, 1999; Camilleri, Quinsey, & Tapscott, 2009; Johnson & Sigler, 2000; Marshall & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2002; Shackelford & Goetz, 2004).

Sexual coercion differs in a number of ways from sexual assault. Unlike sexual assault, where women are far more likely to be victims than men, prevalence rates suggest similar rates of coercion among college men and women, with approximately 30% reporting sexual coercion within their dating relationships (Chan, Straus, Brownridge, Tiwari, & Leung, 2008; Gross, Winslett, Roberts, & Gohm, 2006; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987; Larimer et al., 1999) and the majority of coercive experiences occur in relationships where some type of sexual behavior has already been initiated (Harned, 2005; Livingston et al., 2004; O'Sullivan et al., 1998).

Given the prevalence of sexual coercion among both male and female college students, further study of the impact of coercion on health behaviors is of great import. Sexual coercion is associated with a number of negative outcomes such as lower rates of condom use, higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, increased physical aggression and victimization in the relationship, and poorer psychological and physical health (Blythe et al., 2006; De Visser et al., 2007; Teten, Hall, & Capaldi, 2007). For example, a large study of female college students found that those who were victims of sexual coercion had lower self-esteem, were more socially isolated and reported more depressed mood and social anxiety than did nonvictims (Zweig et al., 1997). Additionally, experiencing sexual coercion has been linked to higher suicidality in college women (Segal, 2009). Of note, one study found that victims of sexual coercion and victims of sexual assault experienced comparable symptom levels on clinical subscales of the Trauma Symptom Inventory (Broach & Petretic, 2006). Thus, sexual coercion appears to be a risk factor for psychological distress and health risk behaviors.

Though past research has identified several negative outcomes associated with sexual coercion, few studies have specifically examined alcohol use in relation to sexual coercion. Larimer and colleagues (1999) did find that sorority and fraternity members who had experienced sexual coercion reported heavier alcohol use and more alcohol-related consequences than did their nonvictimized counterparts. This study did not address possible mediators for this relationship. Thus, there is a clear need for more research examining the link between coercive experiences and alcohol use in both college men and women, as well as research exploring possible mechanisms through which this could occur.

2.2. Drinking to cope

Motivational theories of alcohol use have previously been evaluated in a wide range of contexts and assume that people drink to attain specific desired outcomes (Cooper, 1994). This theory holds that alcohol use is motivated by perceived functions and specific motivations are associated with unique trajectories of use and consequences (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). Applied to victimization experiences, victims may engage in alcohol use as a means of coping with their experience because they perceive that alcohol will help reduce their distress.

Previous research has found support for self-medication models of drinking in women with victimization histories using cross-sectional (Goldstein, Flett, & Wekerle, 2010; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Kaysen et al., 2007; Miranda, Meyerson, Long, Marx, & Simpson, 2002; Ullman et al., 2005) and longitudinal designs (Kaysen et al., 2006; Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997; Schuck & Widom, 2001). Specifically, previous research has found that experiencing a sexual assault was associated with both more alcohol use and negative alcohol-related consequences in community and college samples (Kilpatrick et al., 1997) and that sexual assault victims use alcohol to decrease psychological distress associated with the assault (Khantzian, 1985; Miranda et al., 2002). Thus, alcohol may serve as a negative reinforcer for psychological distress, which ultimately can lead to alcohol misuse and abuse over time. In partial support of this hypothesis, studies have found that women with sexual assault histories report greater motivations for drinking to cope than nonvictimized women (Corbin et al., 2001; Miranda et al., 2002; Ullman et al., 2006). Moreover, greater endorsement of coping motives in sexual assault victims has been associated with heavier alcohol consumption (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Schuck & Widom, 2001; Ullman et al., 2005).

Although drinking to cope has not specifically been tested as a mediator of the relation between sexually coercive experiences and drinking outcomes in college students, research on community samples indicates that drinking to cope plays a role in the broader victimization – drinking relationship. Previous research has shown that drinking to cope mediated the relationships between victimization and problem drinking (Goldstein et al., 2010; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Ullman et al., 2005) and between psychological distress and drinking in recently battered women (Kaysen et al., 2007). Though these studies suggest coping motives mediate alcohol use in victimized women, little is known about how these relationships might function among those who have experienced sexual coercion and even less is known about how men cope with coercive experiences. Given that coercive experiences are more prevalent than other forms of sexual victimization, especially among men, and that these experiences are associated with decreased psychological functioning (De Visser et al., 2007; Zweig et al., 1997) and increased risk for alcohol consumption (Larimer et al., 1999), it is important to consider self-medication models of drinking among victims of sexual coercion.

The present study, therefore, sought to investigate coping motives for drinking as a potential mediator of the relation between sexual coercion and alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences in a large sample of college students. Given the high levels of sexual coercion reported by men and women in college student samples (e.g., Chan et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2006; Koss et al., 1987; Larimer et al., 1999), these constructs were investigated in male and female students. Based on previous findings, sexual coercion was expected to be positively related to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences. Consistent with theories which suggest that people often drink to reduce negative affect (e.g., self-medication), it was expected that the relations between sexual coercion and alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences would be mediated by coping motives for drinking. Although men have less often been studied as victims of sexual coercion, the hypotheses described above were expected to hold for them as well.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The present research represents a cross-sectional secondary analysis of baseline data from a larger prevention trial. Details regarding the larger trial are available elsewhere (Neighbors et al., 2010). Incoming college freshman at a large Northwestern U.S. public university were invited to participate in a Web-based survey as part of a larger social norms intervention study. Out of the 4,103 students who were invited to participate in the study, 2,095 students completed the initial screening assessment (51.1% response rate). Selection criteria for the present research included reporting one or more heavy drinking episodes in the previous month (4+/5+ drinks on an occasion for women/men) and minimum age of 18. This provided a sample of 780 (57.3% female) participants. Participants were an average of 18.18 (SD = .42) years of age at the time of the survey. Ethnicity of participants was 66.1% White, 23.7% Asian, 4.4% Hispanic/Latino, 1.3% Black/African American, 0.5% Native American/American Indian, and 4.1% self-classified as other.

2.2. Procedures

Participants completed an initial 20-minute Web-based screening assessment and were paid $10 for their participation. Participants who completed screening and met the drinking criteria were invited to complete a 50-minute baseline assessment online within the two weeks following the screening assessment as part of a larger, Web-based normative feedback intervention study targeting college student drinking. Participants who completed the baseline assessment were paid $25 for participating in this portion of the study. The Institutional Review Board at the university where the research was conducted approved all aspects of the study.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sexual coercion

The short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2S; Straus & Douglas, 2004) was used to examine sexual coercion within participants’ current or most recent romantic relationship. The scale includes 10 items that assess victimization experiences and 10 items that assess perpetration of intimate partner violence. While the CTS2S is designed to capture both perpetration and victimization experiences of sexual coercion, our analyses focused only on victimization of sexual coercion within the context of college dating relationships with the item: “My partner insisted on sex when I did not want to or insisted on sex without a condom (but did not use physical force).” Response options ranged from: “0=This has never happened before,” “1=Not in the past year, but it did happen before,” “2=Once in the past year,” “3=Twice in the past year,” “4=3-5 times in the past year,” “5=6-10 times in the past year,” “6=11-20 times in the past year,” and “7=More than 20 times in the past year.” The response scale was recoded where scores of “0” indicated that the participant never had the experience and “1” indicated that the participant had experienced the event.

2.3.2. Coping motives

The 5-item coping motives subscale of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (Cooper, 1994) was used to examine drinking to cope in this sample. Participants are provided with the instructions: “Thinking of all the times you drink, how often would you say that you drink for each of the following reasons?” Items include: “To forget your worries”, “Because it helps you when you feel depressed or nervous”, “To cheer you up when you are in a bad mood”, “Because you feel more self-confident and sure of yourself”, and “To forget about your problems”. Response options range from “1=Never/Almost never” to “5=Almost always/Always”. Scores for coping motives represent the mean of the four items. Internal reliability for the subscale was .82.

2.3.3. Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to assess typical weekly drinking in this sample. Participants were instructed to “Consider a typical week during the last three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants were provided with standard drink information and they indicated the typical number of standard drinks they consumed each day of a typical week. Responses were summed to generate a typical weekly drinking variable (WEEK). Past research has established that the DDQ has adequate concurrent validity and test-retest reliability (Marlatt et al., 1998; Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006). Peak drinking (PEAK) and typical frequency of drinking (FREQ) over the previous month were assessed using the Quantity/Frequency/Peak (Q/F/P) Alcohol Use Index (Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999). Participants were instructed to: “Think of the occasion you drank the most this past month. How much did you drink?” Response options ranged from zero to 25 or more drinks. Frequency of drinking was assessed with the item: “How many days of the week did you drink alcohol during the past month?” Response options ranged from “0=I did not drink at all” to “11=Everyday”. The Q/F/P has been widely used to assess college student drinking and has been found to be reliable and valid within this context (Dimeff et al., 1999; Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998).

2.3.4. Alcohol-related negative consequences

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed alcohol-related negative consequences in this sample. The scale consists of 23 items asking how many times in the previous three months each event occurred while drinking or because of alcohol use. Example items are: “Neglected your responsibilities?” and “Kept drinking when you promised yourself not to?” Two items were added to examine the frequency of driving after consuming two and four or more drinks. Responses ranged from “Never” to “More than 10 times” on a 5-point scale. Items were summed to create a composite score of problem drinking. Internal consistency reliability in this study was α = .89.

2.4. Data analysis

Multi-group structural equation modeling (Bollen, 1989; Kline, 2005) with AMOS 18.0 (Arbuckle, 2009; Byrne, 2001) using full-information maximum likelihood estimation was used to evaluate a model with coping as a mediator of the relation between sexual coercion and drinking and between sexual coercion and alcohol-related negative consequences. Sexual coercion, coping, and alcohol-related negative consequences were based on either a single item (sexual coercion) or a single scale (coping and alcohol-related negative consequences) and were therefore specified as manifest variables. Drinking included multiple indicators (peak drinking [PEAK]; frequency of consumption [FREQ]; and number of drinks per week [WEEK]) and was specified as a latent variable. Previous research has shown different indicators of drinking to vary in their associations with alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., Borsari, Neal, Collins, & Carey, 2001). Thus, we used a latent variable to provide a better measure of drinking than would be evident from a single measure.

Models were evaluated using the goodness of fit index (GFI; Bentler & Bonett, 1980), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). For the GFI and the CFI, values approaching 1 are considered to indicate excellent fit. For the RMSEA, values below .05 and .08 are considered to indicate excellent and reasonable fit respectively (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Parameter estimates were conducted using bootstrapped standard errors to accommodate non-normality. Data from 12 participants who were missing data were not included due to software limitations which precluded bootstrapping in the presence of missing data (Arbuckle, 2009; Byrne, 2001).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted to evaluate univariate and multivariate outliers and distributional properties. No participants were excluded on the basis of being outliers. Drinks per week and alcohol-related negative consequences were positively skewed. Analyses were boot-strapped to reduce potential influences of outliers and skewness. The majority of participants reported no sexual coercion. Consequently, sexual coercion was scored dichotomously with participants reporting having been coerced coded as 1 (n = 137; 17.77%) and participants reporting no coercion coded as 0 (n = 634; 82.23%). The proportion of participants reporting having experienced coercion did not differ significantly between men (16.11%) and women (19.00%); χ2 (df = 1, N = 771) = 1.08, p = ns.

3.2. Descriptive information

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for all alcohol-related variables for the full sample and by gender. In addition, t-tests were conducted to test for gender differences. Table 2 presents means and standard deviations by gender with t-tests comparing those who reported having experienced sexual coercion versus those who did not. Table 3 presents zero-order correlations among all variables by gender. Results of t-tests indicated that men and women did not differ in coping reasons for drinking, but that men drank more than women and reported more alcohol-related negative consequences. Results of t-tests also indicated that coerced men endorsed greater levels of drinking to cope, more drinks per week, higher peak number of drinks consumed on one occasion in the previous month, and more alcohol-related negative consequences than non-coerced men. Coerced women endorsed greater levels of drinking to cope and more alcohol-related negative consequences than non-coerced women. Correlations revealed similar relationships among variables for men and women, with correlation coefficients on average being higher among men. Coercion was significantly associated with drinking to cope and alcohol-related negative consequences for men and women but was only significantly associated with drinking for men, and only for two of the three alcohol consumption variables. Effect sizes related to sexual coercion were small with r's ranging from .12 to .27.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for alcohol-related variables by gender.

| Variable | Overall | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t | |

| Drinking to cope | 2.02 | (0.88) | 2.01 | (0.87) | 2.04 | (0.90) | -0.43 |

| Drinks per week | 11.68 | (10.68) | 14.13 | (12.08) | 9.85 | (9.10) | 5.64*** |

| Peak drinks in previous month | 8.76 | (4.13) | 10.31 | (4.50) | 7.61 | (3.41) | 9.54*** |

| Drinking frequency | 4.79 | (1.89) | 4.97 | (1.91) | 4.66 | (1.87) | 2.21* |

| Alcohol-related consequences | 6.94 | (7.80) | 7.83 | (8.71) | 6.28 | (6.99) | 2.77** |

Note. T-tests reflect comparisons between men and women. Degrees of freedom for t-tests ranged from 775 to 778 depending on missing values.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for alcohol-related variables by sexual coercion and gender.

| Men | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coerced (N = 53) | Not Coerced (N = 276) | Coerced (N = 84) | Not Coerced (N = 358) | ||||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | t | |

| Drinking to cope | 2.30 | (0.94) | 1.96 | (0.84) | 2.66** | 2.41 | (0.98) | 1.94 | (0.85) | 4.43*** |

| Drinks per week | 17.36 | (15.11) | 13.53 | (11.41) | 2.11* | 11.17 | (9.47) | 9.59 | (9.03) | 1.43 |

| Peak drinks in previous month | 11.92 | (5.14) | 10.03 | (4.34) | 2.82** | 8.04 | (3.30) | 7.54 | (3.44) | 1.21 |

| Drinking frequency | 5.35 | (2.40) | 4.89 | (2.76) | 1.58 | 4.70 | (1.90) | 4.66 | (1.87) | 0.18 |

| Alcohol-related consequences | 7.77 | (8.61) | 6.77 | (7.34) | 5.01*** | 6.33 | (7.01) | 5.87 | (6.96) | 2.86** |

Note. T-tests reflect comparisons between coerced and not coerced participants. Degrees of freedom for t-tests ranged from 326 to 327 for men and from 438 to 440 for women, depending on missing values.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Correlations among variables by gender.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual coercion | -- | .15** | .12* | .16** | .09 | .27*** |

| 2. Drinking to cope | .21*** | -- | .11* | .15** | .10 | .30*** |

| 3. Drinks per week | .07 | .16** | -- | .65*** | .68*** | .48*** |

| 4. Peak drinks in previous month | .06 | .09 | .57*** | -- | .44*** | .43*** |

| 5. Drinking frequency | .01 | .08 | .59*** | .38*** | -- | .42*** |

| 6. Alcohol-related consequences | .14** | .39*** | .35*** | .29*** | .34*** | -- |

Note. Correlations above the diagonal are for men. Correlations below the diagonal are for women.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.3. Primary results

Two models were evaluated. First, we wanted to consider whether the specified relational paths between variables might adequately describe the population as a whole, without respect to gender. Thus, in our initial model all path coefficients and variances were constrained to be equal for men and women. Means and intercepts were free to vary between men and women. Path coefficients for this model are presented in Figure 1. Error terms were specified as uncorrelated but are not presented for the sake of parsimony. This model provided a reasonable fit to the data, χ2 (15) = 120.37, p < .001, GFI = .950, CFI = .913 RMSEA = .067. Results suggested that overall sexual coercion was positively associated with drinking to cope. Drinking to cope was in turn associated with greater alcohol use and significantly more alcohol-related negative consequences. Coercion had a significant direct relationship with drinking and with alcohol-related negative consequences. Mediation was evaluated by testing indirect effects (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Table 4 provides a summary of total, direct, and indirect effects. Results revealed that overall, there was a significant direct association between sexual coercion and drinking to cope. There was also a significant direct association between sexual coercion and alcohol-related negative consequences and a marginally significant direct association between sexual coercion and alcohol consumption. In support of the overall mediation model, there were significant indirect associations between sexual coercion and drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences through drinking to cope.

Figure 1. Overall model.

Tests of parameter estimates were bootstrapped using 1000 drawn samples. + p < .10. * p < .05. **p < .01.

Table 4.

Direct, indirect, and total standardized effects.

| Overall Sample | Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Criterion | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects |

| Sexual Coercion | Drinking to cope | .180** | -- | .180** | .142* | -- | .142* | .206** | -- | .206** |

| Alcohol consumption | .074† | .024** | .098* | .127† | .018* | .145* | .037 | .029** | .066 | |

| Alcohol-related consequences | .096* | .090** | .185** | .163** | .093* | .257** | .040 | .093** | .132** | |

| Drinking to Cope | Alcohol consumption | .134** | -- | .134** | .127† | -- | .127† | .141** | -- | .141** |

| Alcohol-related consequences | .266** | .057** | .323** | .213** | .055† | .268** | .323** | .056** | .379** | |

| Alcohol Consumption | Alcohol-related consequences | .428** | -- | .428** | .434** | -- | .434** | .397** | -- | .397** |

Note. Effects are standardized. Tests of effects are based on bootstrapped standard errors.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

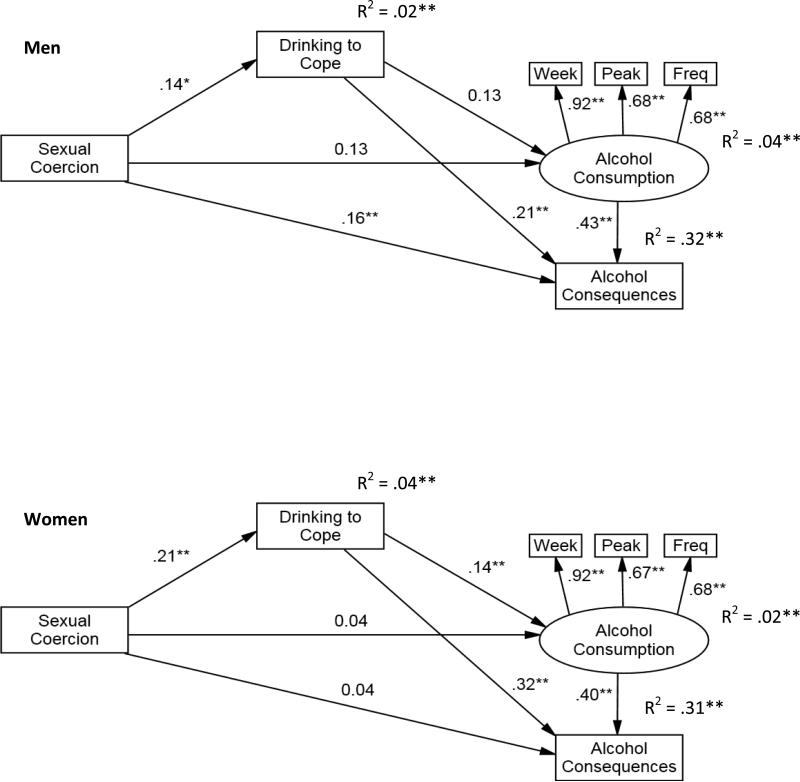

In our second model, we were interested in considering whether the model might work differently for women than men. Thus, we modified the above model, allowing all path coefficients and variances to differ between men and women, with the exception of indicator paths and variances for drinking. This model provided a good fit to the data and was a significantly better fit than the constrained model, χ2Δ (9) = 19.76, p < .05; χ2 (24) = 100.62, p < .001, GFI = .958, CFI = .923, RMSEA = .077. Path coefficients are presented in Figure 2 for women (bottom) and men (top). Direct, indirect, and total effects are presented in Table 4. Results for women indicated that sexual coercion was positively associated with drinking to cope and drinking to cope was in turn associated with greater alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences. For women, coercion did not have a significant direct relationship with drinking or alcohol-related negative consequences. Moreover, only indirect associations were evident between sexual coercion and alcohol-related outcomes, through drinking to cope.

Figure 2. Model for men and women.

Tests of parameter estimates were bootstrapped using 1000 drawn samples. + p < .10. * p < .05. **p < .01.

For men, results similarly indicated that sexual coercion was associated with drinking to cope and drinking to cope was in turn associated with more alcohol-related negative consequences. In contrast to women, for men the association between drinking to cope and drinking was only marginally significant (p < .06). Furthermore, in contrast to women, for men, there was a significant direct association between sexual coercion and alcohol-related negative consequences and a marginally significant direct association between sexual coercion and drinking and between sexual coercion and alcohol-related negative consequences. Indirect paths from sexual coercion to drinking and to alcohol-related negative consequences were both significant. Thus, among men there was less evidence for drinking to cope as a primary explanation for the association between sexual coercion and problematic drinking.

4. Discussion

The present study bridges an important gap in the literature by evaluating a coping model of alcohol use and related negative consequences for both male and female college students who have experienced sexual coercion. This research extends previous work in several ways. Previous research examining gender differences in responses to sexual coercion is scarce at best, and no studies of which we are aware have examined coping alcohol-related responses among male victims of coercion. Though research exploring the link between victimization experiences and drinking has begun to consider coping-related motivations for drinking as a potential mechanism for this relationship (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Kaysen et al., 2007; Ullman et al., 2005), coping models have not specifically been tested among victims of sexual coercion. Given the frequency with which sexual coercion occurs, understanding more about what factors increase risk for possible consequences has important clinical implications, especially for those working with college populations. Prospective studies have found relationships between increased alcohol use and consequences and risk for revictimization (Messman-Moore, Ward, & Brown, 2009), which further highlights the importance of understanding potential mechanisms for the relationship between sexual coercion and alcohol outcomes. Our findings suggest drinking to cope is an important factor in explaining the relationship between experiencing sexual coercion and both alcohol use and problems, albeit in somewhat different ways for men and women.

Interestingly, our results suggest women who have experienced sexual coercion may drink and thus may experience problems associated with their drinking predominantly to the extent to which they use alcohol as a way to cope. Findings suggest that women who have experienced sexual coercion may benefit from interventions that emphasize alternative means of coping with distress as a means of reducing alcohol use and consequences. Findings also suggest that interventions that exclusively focus on descriptive norms and positive alcohol expectancies may be somewhat less effective for this population.

In our sample, men who experienced sexual coercion did drink more and had more problems with alcohol than those who had not experienced sexual coercion. However, for men drinking to cope did not mediate the relationship between sexual coercion and alcohol use. Drinking to cope partially mediated the relationship between sexual coercion and alcohol-related negative consequences. There were also direct relationships between sexual coercion and both drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences for men. This suggests that perhaps for men, alcohol-related negative consequences and sexual coercion are related in ways that include drinking to cope with distress, but that drinking behavior itself is less motivated by coping motives. It is possible that, for men in particular, other motives for drinking such as social or enhancement motives may be stronger predictors of actual alcohol consumption, regardless of whether they have experienced sexual coercion. Further attention regarding coercive experiences and responses to those experiences among men is warranted and future research should evaluate other potential mediators and moderators of the relationship between sexual coercion and alcohol use and problems.

While these results are consistent with a self-medication model of drinking, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes confirmation of causal sequence and other plausible explanations for the association between coercion and drinking cannot be ruled out. By their nature, these research questions would best be addressed using longitudinal data collection and analysis. By retrospectively assessing coercion and concurrently assessing drinking motives and alcohol use and consequences, relationships between coping motives and drinking may be inflated due to the confound of time (Briere, 1997). In addition, the cross-sectional design used in the present study cannot truly disentangle the timeline between coercion, coping motives, and drinking behavior. Previous research has established that drinking increases risk of sexual coercion (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher & Martin, 2009) and that prior victimization also increases risk for heavy drinking (Messman-Moore, Ward, & Brown, 2009). It is likely that a cyclical relationship exists such that sexual victimization increases risk for heavy drinking, which in turn increases risk for re-victimization (Fortier et al., 2009).

While the rates of coercion in our sample (18%) were somewhat lower than what has been found in other college samples (30%), our sample consisted of incoming college freshman. Findings may be different in more heterogeneous samples of college students or general population samples. Students in our sample were likely reporting on relationship behaviors prior to entering college at the time of the survey, which may help to explain the lower prevalence rate in our study as compared to other college samples. It is also important to note that only students who reported a heavy drinking episode in the previous month were selected to participate which may limit the generalizability of our findings. The restricted sample may have also accounted for the lack of association between sexual coercion victimization and alcohol consumption among women and relatively weak association found among men in our sample. While, at first glance, these findings are contrary to what we expected, they are in line with previous research that has found that alcohol-related negative consequences are a better indicator of problem drinking in college samples (e.g., Mallet, Marzell, & Turrisi, 2011) given that rates of alcohol consumption are so high in this population. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in samples consisting of a broader range of individuals including college students across their academic career and with a range of drinking behavior as well as examining whether these relationships look similar in dating couples that did not go to college.

Rates of coercion in our study may have also been underrepresented due to the use of a single item measure of coercion. Future research in this area calls for replication using a more detailed measure of sexual coercion. Scales such as the Sexual Experiences Scale (Koss et al., 1987) may help tease apart the roles that specific sexually coercive experiences as well as the frequency of those experiences play in leading to drinking and related problems. Moreover, although participants were informed that their answers would remain confidential, participants’ reports were not anonymous, which could have led to underreporting of coercive experiences in our sample.

In addition, it is important to note that our measure of coping motives was not specific to victimization or coercion experiences, thus it does not specifically measure whether these coping motives occurred in response to the victimization. Also given the measurement and methodology limitations, we cannot ascertain what symptoms specifically participants were self-medicating or whether these symptoms were directly related to the sexual coercion. Items generally reflect anxiety, depression, and avoiding psychological distress. Coping motivated drinking has generally been associated with heavier alcohol use and higher risk of consequences (Park & Levensen, 2002). Relatedly, although our study has focused on coping motives as a response to victimization it also may reflect a more general avoidant coping style, which could in turn increase risk of experiencing coerced sex (Fortier et al., 2009).

Nonetheless, these results are promising and underscore the need for longitudinal and prospective studies to address the relation between coercion and drinking, including examination of potential mediators of this relationship (e.g., coping motivations for drinking). Additionally, both sexual coercion experiences and drinking to cope would be important potential moderators to examine in future clinical trials on interventions for risky drinking. It is possible that other variables such as a general maladaptive coping style might account for the observed results. These issues underscore the need for additional longitudinal data assessing coping and drinking in recent victims of sexual coercion. Our results, more broadly, highlight the importance of assessing relationship issues, including coercion among college dating couples and the role that alcohol plays in dating relationships. Despite the limitations, this study represents an important first step in exploring the role of drinking to cope in the coercion – drinking relationship among male and female college students.

4.1. Conclusions

In sum, this study represents the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate a coping model for drinking and related negative consequences in a sample of victims of sexual coercion. Further, this study represents one of a few to explore alcohol-related responses in male victims of coercion. Our results suggest drinking to cope is an important factor in explaining the relationship between experiencing sexual coercion and alcohol use and related problems among women, and provides a partial explanation for the relationship between coercion and alcohol-related problems among men. Future avenues for research should further evaluate this model in more diverse longitudinal samples of college students as well as young adults who did not go to college using more detailed measures of coercion. Additionally, future research should investigate alternative models for explaining the coercion – alcohol relationship among men. Inclusion of alcohol-related topics when intervening with students who have experienced coercion is warranted.

Research Highlights.

Sexual coercion and heavy drinking frequently occur in college populations.

Few studies have directly examined coping motives for drinking as a mediator.

Coping motives were examined in the relation between coercion and drinking.

Results support coping motives as a mediator for women and partial mediator for men.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this article was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA014576.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 18 User's Guide. SPSS, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Basile K. Rape by acquiescence: The ways in which women ‘give in’ to unwanted sex with their husbands. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:1036–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe MJ, Fortenberry JD, Temkit M, Tu W, Orr DP. Incidence and correlates of unwanted sex in relationships of middle and late adolescent women. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:591–595. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Neal DJ, Collins SE, Carey KB. Differential utility of three indexes of risky drinking for predicting alcohol problems in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:321–324. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Psychological assessment of adult posttraumatic states. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Broach JL, Petretic PA. Beyond traditional definitions of assault: Expanding our focus to include sexually coercive experiences. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Stuctural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; London, England: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri JA, Quinsey VL, Tapscott JL. Assessing the propensity for sexual coaxing and coercion in relationships: Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Tactics to Obtain Sex Scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:959–973. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Straus MA, Brownridge DA, Tiwari A, Leung WC. Prevalence of dating partner violence and suicidal ideation among male and female university students worldwide. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 2008;53:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, McNair LD, Seals KL. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S, DiLillo D. ‘You would if you loved me’: Toward an improved conceptual and etiological understanding of nonphysical male sexual coercion. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:513–532. [Google Scholar]

- De Visser RO, Rissel CE, Richters J, Smith AMA. The impact of sexual coercion on psychological, physical, and sexual well-being in a representative sample of Australian women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:676–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier MA, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL, Peugh J, DeNardi KA, Gaffey KJ. Severity of child sexual abuse and revictimization: The medicating role of coping and trauma symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:308–320. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Flett GL, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment, alcohol use and drinking consequences among male and female college students: An examination of drinking motives as mediators. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:636–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Winslett A, Roberts M, Gohm C. An examination of sexual violence against college women. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:288–300. doi: 10.1177/1077801205277358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned M. Understanding women's labeling of unwanted sexual experiences with dating partners. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:374–413. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Schroeder RD, Bradley C, Kaplan LM, Angel RJ. The long-term health consequences of relationship violence in adulthood: An examination of low-income women from Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:1645–1650. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson IM, Sigler RT. Forced sexual intercourse among intimates. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1820–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. College women's experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57:639–649. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lydum AR, Anderson BK, Turner AP. Male and female recipients of unwanted sexual contact in a college student sample: Prevalence rates, alcohol use and depression symptoms. Sex Roles. 1999;40:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, et al. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JA, Buddie AM, Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C. The role of sexual precedence in verbal sexual coercion. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating Mediated Effects in Prevention Studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet KA, Marzell M, Turrisi R. Is reducing drinking always the answer to reducing consequences in first-year college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:240–246. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Varying forms of husband sexual aggression: Predictors and subgroup differences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:286–296. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM, Brown AL. Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Marx BP, Simpson SM. Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:205–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, et al. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan LF, Byers ES, Finkelman L. A comparison of male and female college students’ experiences of sexual coercion. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levensen MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems, and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck AM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and alcohol symptoms in females: Causal inferences and hypothesized mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1069–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DL. Self-reported history of sexual coercion and rape negatively impacts resilience to suicide among women students. Death Studies. 2009;33:848–855. doi: 10.1080/07481180903142720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford TK, Goetz AT. Men's sexual coercion in intimate relationships: Development and initial validation of the Sexual Coercion in Intimate Relationships Scale. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:541–556. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.541.63681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Parks KA. The role of women's alcohol consumption in sexual victimization. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1996;1:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Teten AL, Hall GCN, Capaldi DM. Use of coercive sexual tactics across 10 years in at-risk young men: Developmental patterns and co-occurring problematic dating behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;38:574–582. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. A critical review of field studies on the link of alcohol and adult sexual assault in women. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8:471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas H, Townsend S, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual assault in a national sample of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:603–625. [Google Scholar]

- White H, Labouvie E. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig J, Barber B, Eccles J. Sexual coercion and well–being in young adulthood: Comparisons by gender and college status. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Crockett LJ, Sayer A, Vicary JR. A longitudinal examination of the consequences of sexual victimization for rural young adult women. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:396–409. [Google Scholar]