Abstract

Background

We have shown that thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) has a direct inhibitory effect on osteoclastic bone resorption and that TSH receptor (TSHR) null mice display osteoporosis. To determine the stage of osteoclast development at which TSH may exert its effect, we examined the influence of TSH and agonist TSHR antibodies (TSHR-Ab) on osteoclast differentiation from murine embryonic stem (ES) cells to gain insight into bone remodeling in hyperthyroid Graves' disease.

Methods

Osteoclast differentiation was initiated in murine ES cell cultures through exposure to macrophage colony stimulation factor, receptor activator of nuclear factor кB ligand, vitamin D, and dexamethasone.

Results

Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive osteoclasts formed in ∼12 days. This coincided with the expected downregulation of known markers of self renewal and pluripotency (including Oct4, Sox2, and REX1). Both TSH and TSHR-Abs inhibited osteoclastogenesis as evidenced by decreased development of TRAP-positive cells (∼40%–50% reduction, p = 0.0047), and by decreased expression, in a concentration-dependent manner, of osteoclast differentiation markers (including the calcitonin receptor, TRAP, cathepsin K, matrix metallo-proteinase-9, and carbonic anhydrase II). Similar data were obtained using serum immunoglobulin-Gs (IgGs) from patients with hyperthyroid Graves' disease and known TSHR-Abs. TSHR stimulators inhibited tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA and protein expression, but increased the expression of osteoprotegerin (OPG), an antiosteoclastogenic human soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor кB ligand receptor. Neutralizing antibody to OPG reversed the inhibitory effect of TSH on osteoclast differentiation evidencing that the TSH effect was at least in part mediated by increased OPG.

Conclusion

These data establish ES-derived osteoclastogenesis as an effective model system to study the regulation of osteoclast differentiation in early development. The results support the observations that TSH has a bone protective action by negatively regulating osteoclastogenesis. Further, our results implicate TSHR-Abs in offering skeletal protection in hyperthyroid Graves' disease, even in the face of high thyroid hormone and low TSH levels.

Introduction

Bone density measurements have demonstrated that bone loss is common in patients with overt hyperthyroidism (1). Decreases in bone mass have been observed even in patients with mild (subclinical) hyperthyroidism, where thyroid hormones are within the normal range, but thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is low or undetectable (2,3) and both women and men with TSH in the low normal range have lower bone density measurements (4,5). Nevertheless, these bone changes have still been considered secondary to thyroid hormone excess (6) via the action of tri-iodothyronine (T3) receptors (7).

We first reported that the hypothyroid TSH receptor (TSHR) knockout (KO) mouse, and even haploinsufficient mice with normal thyroid hormone levels had decreased bone mass (8). This observation has since been claimed to be purely secondary to the hypothyroidism and our observation in the euthyroid haploinsufficient mice ignored (9). We subsequently showed that the TSHR was expressed in both osteoclasts and osteoblasts, and that TSH reduced osteoclast activity, which in turn was related to decreased local production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) (10). While others were unable to show such TSH effects using even high doses of TSH in vitro (9), we have continued to obtain supportive data. For example, low doses of TSH increased bone volume and improved the microarchitecture in ovariectomized rodents (11,12) at a time when there was no increase in serum thyroid hormones. In humans, a significant inverse correlation has been noted between serum TSH levels and bone turnover markers, which were independent of serum free thyroxine and T3 levels (13). Although there are no available data on similar effects on the skeleton of agonist TSHR antibodies (TSHR-Abs) found in hyperthyroid Graves' disease, there is a distinct possibility that such antibodies may bind to and activate the skeletal TSHR. In support of this concept is a recent report that found an inverse relationship between bone density loss and TSHR-Ab levels (14).

Both complete and partial absence of the TSHR in the TSHR-deficient mouse stimulated osteoclast differentiation (8). Since this was observed in heterozygotes, which were euthyroid, it was not possible to explain such effects on the basis of thyroid hormone influences. In contrast, the targeted overexpression of the TSHR solely in osteoclasts in transgenic mice attenuated osteoclastogenesis (10). We have also attributed the antiosteoclastogenesis action of TSH, in part, to the suppression of TNFα through a transcriptional effect (10). This was further demonstrated by the complete rescue of the enhanced osteoclastogenesis of TSHR-deficiency in double homozygote mice in which both the TSHR and TNFα genes were deleted (10). Such genetic evidence, together with our pharmacological studies, makes a compelling case for a role of the TSHR in regulating osteoclastic bone resorption with opposite effects to thyroid hormone.

The present study, therefore, had three objectives: (i) to determine whether TSH specifically affected osteoclastogenesis in early development by using a stem cell model; (ii) to study whether stimulating TSHR-Abs mimic the osteoclast-inhibitory effects of TSH; and (iii) to investigate whether TNFα is the sole mechanism of this action or whether alterations in the human soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor кB ligand (RANK-L)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) pathway also mediate these effects.

To examine these possibilities in the early stage of osteoclast development, we have utilized a culture system in which murine embryonic stem (ES) cells were induced to form osteoclasts by their simultaneous exposure to a cocktail of four osteoclast differentiation factors (ODFs).

Materials and Methods

Growth and maintenance and differentiation of ES cells

Murine W9.5 ES cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 4.5 g/L L-D-glucose, supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (StemCell Technologies, Inc.), 50 U/mL/50 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 1.5 × 10−4 M monothioglycerol, and 10 ng/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (StemCell Technologies, Inc.) on 0.1% gelatin-coated culture dishes, and were cultured in a humidified chamber in a 5% CO2-air mixture at 37°C. ES cells cultures were passaged at 1:3–5 ratios every 2 days. Undifferentiated ES cells were trypsinized and plated at 5 × 104 cells/cm2 in six-well plates; from days 4 to 12, osteoclast-like cells were induced by addition of ODFs (15): 10 ng/mL human macrophage colony-stimulation factor (M-CSF), 50 ng/mL RANKL, 10−8 M 1a,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1a, 25(OH)2D3), and 10−7 M dexamethasone (Dex) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) into the medium. The medium was changed every 2 days. On day 12, the differentiated cell population was immediately fixed and used for cytochemical staining, or harvested.

TSH and TSHR-Ab treatment of ODF cultures

From day 4 to 12, semi-purified TSH (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.), or on day 10, hamster monoclonal TSHR-Ab MS1 (16) or human monoclonal TSHR-Ab M22 (kindly supplied by RSR Ltd.) (17), was added (1 μg/mL). We have previously compared the TSHR stimulating activity of these two monoclonal antibodies with TSH stimulating activity (18). At these concentrations, M22 was equivalent to TSH, whereas MS-1 had ∼60% of the activity. Serum IgG fractions, purified on Protein G columns (Amersham Biosciences), from two patients with Graves' disease and TSHR-Abs, and from a normal control, were also used (1 mg/mL). On day 12, the cells were collected for analysis using ODF-only treated cells as control.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining of osteoclast-like cells differentiated from ES cells was performed as described (8) in which TRAP-positive cells developed an intense red color. The numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells, those containing three or more nuclei, were counted using ocular grids. Three wells were measured for each condition and these results were expressed as mean ± error of the mean.

Assay of resorbing activity of osteoclast-like cells

Undifferentiated ES cells were plated on a calcium phosphate apatite-coated plate (Osteoclast Activity Assay Substrate, OAAS™ from OCT USA, Inc.) at 1 × 104 cells/well. On day 12, when TRAP-positive osteoclast-like cells appeared, the cells were removed with a solution of 5% sodium hypochlorite. Bone resorption activity was measured by direct observation under phase-contrast microscopy. Resorption pit numbers were determined by light microscopy in multiple random fields.

RNA isolation

Total RNA (TRIzol; Invitrogen, Life Technologies) was determined on the basis of absorbance at 260 nm, and its purity was evaluated by the ratio of absorbance at 260/280 nm (>1.9). After digestion of genomic DNA by treatment with Ambion's TURBO DNA-free™ DNase I (Ambion), total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with random hexamers (Advantage; Clontech).

Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reactions

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to assess the expression of cathepsin K (CTSK), matrix metallo-proteinase-9 (MMP-9), TRAP, carbonic anhydrase II (CA2), and calcitonin receptor (CTR) mRNAs during osteoclast-like cell differentiation. Quantitative RT-PCRs (qRT-PCRs) were performed using the Applied Biosystem StepOnePlus Real-time PCR system. The reactions were established with 10 μL of SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.4 μL (0.2 μM) of sense/anti-sense gene-specific primers, 2 μL of cDNA, and DEPC-treated water to a final volume of 20 μL. The PCR mix was denatured at 95°C for 60 seconds before the first PCR cycle. The thermal cycle profile was denaturing for 45 seconds at 95°C; annealing for 30 seconds at 57°C–60°C (dependent on primers); and extension for 60 seconds at 72°C. The following primers were used: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sense, 5′- AAC GAC CCC TTC ATT GAC-3′; GAPDH antisense, 5′- TTC ACG ACA TAC TCA GCA C-3′; CTR sense, 5′-CCA TTC CTG TAC TTG GTT GGC-3′; CTR antisense, 5′-AGC AAT CGA CAA GGA GTG AC-3′; TRAP sense, 5′-TAC AGC CCC CAC TCC CAC CCT-3′; TRAP antisense, 5′-TCA GGG TCT GGG TCT CCT TGG-3′; MMP-9 sense,5′-CCT GTG TGT TCC CGT TCA TCT-3′; MMP-9 antisense, 5′-CGC TGG AAT GAT CTA AGC CCA-3′; CTSK sense, 5′-GGA AGA AGA CTC ACC AGA AGC-3′; CTSK antisense, 5′-GTC ATA TAG CCG CCT CCA CAG-3′; CA2 sense, 5′- CAC CCT TCC AAG ATC TTA TA-3′; CA2 antisense, ATC CAT TGT GTT GTG GTA TG-3′; OPG sense, 5′-TGA GTG TGA GGA AGG GCG TTA C-3′; OPG antisense, 5′-TTC CTC GTT CTC TCA ATC TC-3′; TNFα sense, 5′-TCC AGG CGG TGC CTA TGT CT-3′; TNFα antisense, 5′-GTT TGA GCT CAG CCC CCT CA-3′. A total of 40 PCR cycles were used. PCR efficiency, uniformity, and linear dynamic range of each qRT-PCR assay were assessed by the construction of standard curves using DNA standards. An average Ct (threshold cycle) from triple assays was used for further calculation. For each target gene, the relative gene expression was normalized to that of the GAPDH housekeeping gene. Data presented (mean) are from three independent experiments in which all sample sets were analyzed in triplicate.

TSHR functional assessment

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) assays were performed as previously described (18). Briefly, ES cells were plated at a density of ∼1.0 × 105 cells/well on a 24-well plate. On the 12th day, cultured cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of TSH for 1 hour with 2 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine. Intracellular cAMP generation was measured by enzyme immunoassay (Assay Designs, Inc.).

Statistical analyses

Statistically significant differences were analyzed by analysis of variance or unpaired Student's t-test as appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Values were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

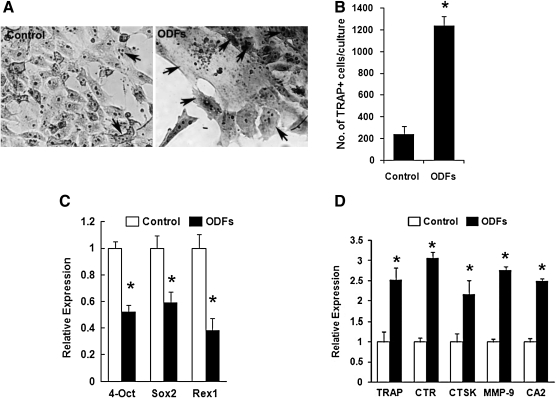

Characterization of the osteoclast differentiation model

Osteoclasts are large, multinucleated syncytia of hematopoietic origin, specifically the monocyte-macrophage lineage, and strongly express the enzyme TRAP. We differentiated ES cells into osteoclasts, and microscopic examination suggested that ∼10% cells had differentiated into TRAP-positive multinucleated cells after 12 days (Fig. 1A, B). Critical expression levels of the stem cell transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, and REX1, which are required to sustain stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency, were appropriately downregulated in the ES cells after such differentiation (Fig. 1C). As expected, the gene expression profile of the differentiated cells favored osteoclastogenesis as evidenced by the enhanced transcriptional expression of the ODFs—TRAP, CTR, CTSK, MMP-9, and CA2 (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Osteoclast differentiation from murine ES cells using four ODFs. ES cells were cultured without (control) or with medium containing ODFs for 12 days, allowing the formation of osteoclasts. Cultured cells were fixed and then stained as described. (A) The cells stained for TRAP with enhanced intensity when cultured with ODFs (right panel) in contrast to control cells (left panel). Osteoclasts were multinucleated cells of various sizes (indicated by arrows). (B) The development of osteoclasts was measured as the increase in TRAP-positive multi-nucleated cells containing three or more nuclei, which were counted using grids placed in the ocular lens of the microscope. Three wells were measured in total for each experimental condition and results expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures (*p < 0.01). (C) Loss of stemness was assessed by real-time qPCR measurements for the expression of ES cell markers Oct4, Sox2, and REX1 in cells cultured with ODFs for 12 days. Undifferentiated ES cells were used as control. Significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.01). (D) Differentiation of osteoclasts was confirmed by real-time qPCR measurements for the transcriptional expression of osteoclast-specific markers, including TRAP, CTR, CTSK, MMP-9, and CA2, in the cultured cells without (filled clear) or with (filled black) ODFs. Significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.01). ES, embryonic stem; ODFs, osteoclast differentiated factors; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; SEM, standard error of the mean; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; CTSK, cathepsin K; MMP-9, matrix metallo-proteinase-9; CA2,carbonic anhydrase II; CTR, calcitonin receptor.

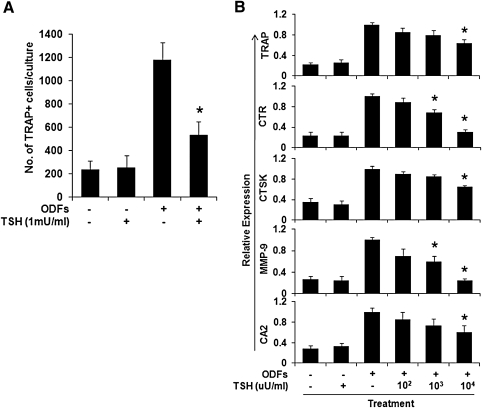

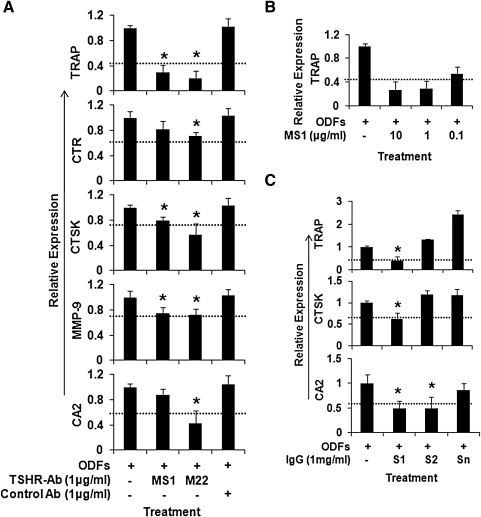

Effects of TSH and TSHR-Abs on TRAP-positive multinucleated cell formation and osteoclast gene expression

The number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells formed from ES cells cultured with four ODFs was significantly decreased (54.72% ± 3.4%, p = 0.0047) by the addition of TSH (up to 1 mU/mL) at day 4 of differentiation (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the transcription of osteoclast gene markers, including CTR, TRAP, MMP-9, and CA2, were also decreased by TSH in a dose-dependent fashion when assayed using real-time PCR although changes in CTSK were minor (Fig. 2B). Similar experiments performed with equivalent doses of monoclonal TSHR-Abs (MS-1 and M22) gave essentially the same results with significant inhibition of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3A). The transcription of osteoclast gene markers, including TRAP, CTR, CTSK, MMP-9, and CA2, were decreased by MS-1 in a dose-dependent manner. Figure 3B illustrates the MS-1-induced TRAP response as an example. To ascertain if these effects were also mimicked by Graves' disease patients TSHR-Abs, IgG fractions from two patients with Graves' disease and a control IgG were used in 1 μg/mL concentrations. One patient's IgG (S1) markedly inhibited TRAP, CTSK, and CA2, whereas the second (S2) was only moderately effective (Fig. 3C). The control IgG (Sn) had no inhibitory effect and rather enhanced the expression of these genes.

FIG. 2.

The effect of TSH on osteoclast differentiation. ES cells were cultured with the four ODFs for 12 days, allowing the formation of osteoclasts in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of TSH as indicated. (A) TSH decreased the number of TRAP-positive multi-nucleated cells. TRAP-positive multi-nucleated cells containing three or more nuclei were counted. Three wells were counted in total for each condition and results expressed as mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. (B) TSH decreased specific osteoclast markers in cultured cells. The cells were subjected to real-time qPCR analysis of TRAP, CTR, CTSK, MMP-9, and CA2 gene expression. Values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression. TSH showed a dose-dependent decrease in all osteoclast markers. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *The p-value comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH was < 0.01. TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

FIG. 3.

The effects of TSHR-Ab or Graves' Disease IgG on the differential expression of osteoclast markers. (A) Stimulating TSHR-Abs inhibit osteoclast marker expression. The effects of monoclonal TSHR-Abs MS1 and M22 (1 μg/mL) on osteoclast markers in cultured ES cells with ODFs are illustrated. There was a marked decrease in all osteoclast markers with MS1 and M22 treatment, whereas this decrease was not observed with control antibody (*p < 0.01). (B) The transcription of osteoclast gene markers, TRAP, measured by qPCR, was decreased by MS-1 in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Serum IgG from two patients with Graves' disease and TSHR-Abs decreased specific osteoclast gene expression. Sample S1 clearly inhibited TRAP, CTSK, and CA2, whereas S2 was less effective. The normal control IgG (Sn) showed no inhibition. The p-value comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of IgG fractions was < 0.01. The dashed line in all the panels indicates the inhibition caused by TSH at 1 mU/mL within the same experiment. These data are typical of three independent experiments. TSHR-Ab, TSH receptor antibody; IgG, immunoglobulin-G.

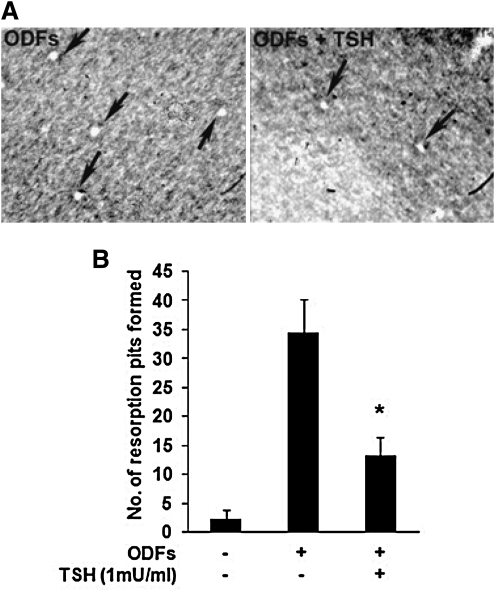

Effects of TSH on the number of osteoclasts differentiated from ES cells

To directly evaluate the effect of TSH on the number of osteoclasts measured by their resorption activity, the ES cell cultures were seeded in OAAS plates without or with four ODFs in the absence or presence of TSH for 12 days. The cells were then removed by a hypochorite wash and the number of resorption pits counted. It was found that the number of resorption pits decreased significantly with the addition of TSH to the culture (Fig. 4A, B), confirming the reduction in osteoclast differentiation.

FIG. 4.

Effects of TSH on the resorption activity of osteoclasts from ES cells cultured with four ODFs. ES cells were cultured on calcium-phosphate apatite-coated plates with or without ODFs in the absence or presence of TSH (1 mU/mL) for 12 days. When TRAP-positive osteoclasts appeared, the cells were removed with a solution of 5% sodium hypochlorite and pits (clear areas) were counted microscopically. (A) Resorbed lacunae (arrows) on the plates were photographed under an inverted microscope ( × 200). Note that compared with ODFs treatment, TSH (1 mU/mL) significantly decreased the resorption activity of osteoclasts. (B) The number of resorption pits in TSH− and TSH+ cultures was determined by light microscopy in five randomly chosen fields. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures. The p-value, calculated by comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH, was < 0.01.

Expression of TSHR in osteoclasts from ES cells

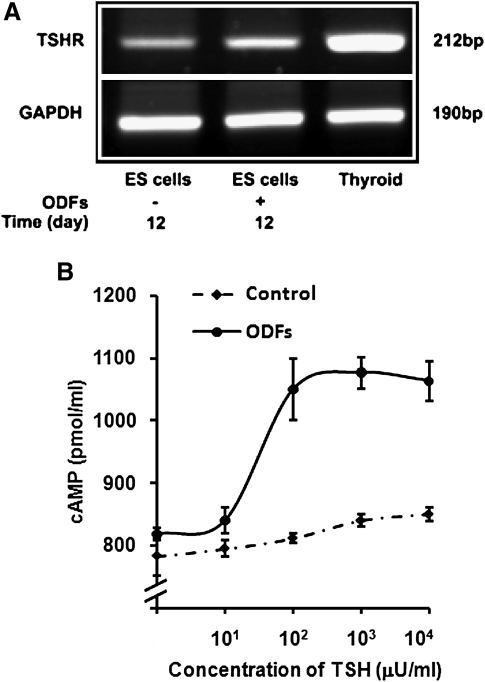

We first investigated the expression of the TSHR in osteoclasts differentiated from ES cells using RT-PCRs. These RT-PCR studies displayed the expected TSHR species, indicating that the differentiated osteoclast precursor cultures maintained normal TSHR expression, as seen to a lesser extent with the undifferentiated ES cells (Fig. 5A). This was confirmed by testing TSHR function in osteoclast precursor cultures from undifferentiated ES cells and ODF-treated ES cells by TSH-stimulated cAMP generation. A dose-dependent cAMP response to TSH was observed (Fig. 5B). This analysis demonstrated that the ODF-cultured ES cells maintained fully functional TSHRs.

FIG. 5.

Expression of TSHR in osteoclasts differentiated from ES cells. (A) Reverse transcription–PCR provided evidence for TSHR expression in osteoclast cultures from ES cells incubated without or with four ODFs for 12 days. Undifferentiated ES cells and mouse thyroid cells were used as negative and positive controls. (B) TSH induced dose-dependent cAMP generation in ODF-cultured ES cells. The ES cells were cultured with ODFs for 12 days and intracellular cAMP levels were measured by enzyme-immunoassay. Control cells were undifferentiated ES cells. TSH treatment of ODF cultured cells lead to a low level dose-dependent induction of cAMP. Non-ODF-treated ES cells showed only a minimal response. Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing wild-type human TSHR (JPO9 cells) (18) were used as a positive control (not illustrated). cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

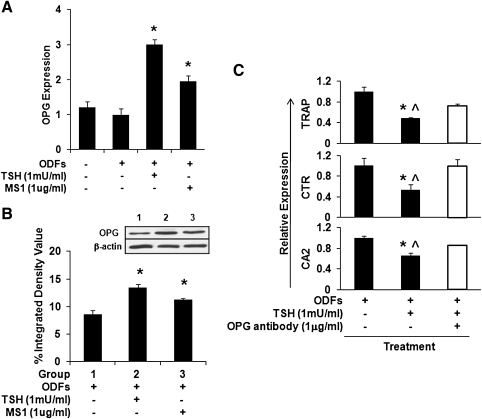

Effect of TSH and TSHR-Abs on OPG during osteoclast differentiation

Osteoclast differentiation is regulated by the RANK/RANKL/OPG ligand–receptor system. The binding of RANK by RANKL induces differentiation of osteoclasts (19,20). OPG acts as a decoy receptor for RANKL, preventing it from binding to and activating RANK, and inhibiting the development of osteoclasts. Thus, osteoclast differentiation is markedly affected by the ratio of RANKL:OPG. OPG expression levels were not increased in our untreated ODFs culture system. However, OPG transcription was markedly increased in response to TSH or MS1 TSHR-Ab when assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 6A) and which reflected a corresponding increase in OPG protein as observed by Western blotting (Fig. 6B). While TSH induced OPG secretion, it also reduced osteoclastogenesis as shown in Figure 2B. This influence was partly neutralized by antibody to OPG (Fig. 6C), indicating that OPG was important for this full effect. Thus, TSH decreased osteoclast differentiation from ES cells at least in part via an increase in the OPG levels within the culture.

FIG. 6.

Expression of OPG levels in differentiated ES cell cultures. All cells were cultured with four ODFs for 12 days. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of OPG mRNA levels in the cultured cells with ODFs in the presence of TSH or TSHR stimulating antibody MS1 as indicated. TSH or MS1 antibody increased the gene expression of OPG in the ODF-treated ES cells. Values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression. The results are representative of three independent experiments. Significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.01) comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH or MS1 antibody. (B) Total lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for detection of OPG using anti-OPG (1 μg/mL) (inset). β-actin served as a control. There was a significant induction of OPG with TSH or MS1 treatment. Significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.01) comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH or MS1 antibody. (C) Attenuation of osteoclast markers by neutralizing antibody to OPG on the TSH treated cells. mRNA expression levels were analyzed by real-time qPCR in the absence or presence of TSH and neutralize OPG antibody as indicated. Anti OPG treatment reversed the suppression of TSH on the osteoclast markers. The p-value was calculated comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH (*p < 0.01) or ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH and OPG antibody (^p < 0.01). OPG, osteoprotegerin.

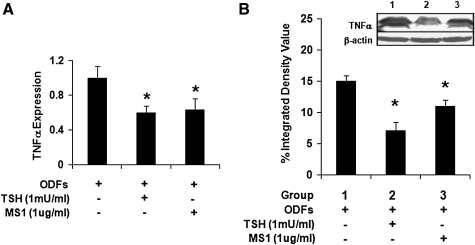

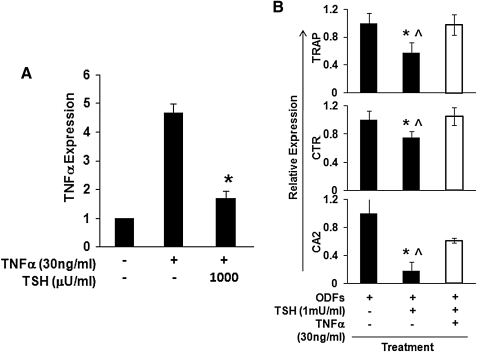

Effects of TSH on TNFα during osteoclast differentiation

In contrast to OPG, TNFα has the potential to induce osteoclast differentiation and activation (21–23). The increased osteoclastogenesis seen in TSHR null mice was associated with increased TNFα production. In keeping with these previous observations, we found that TSH, MS1, and TSHR-Ab decreased TNFα mRNA in the ES culture model (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the decreased TNFα mRNA expression, the protein level was similarly decreased by TSH or MS1 antibody (Fig. 7B). However, TNFα expression was enhanced by recombinant TNFα in the differentiated ES cells over 12 days (Fig. 8A), but this TNFα-induced TNFα mRNA expression was also significantly attenuated by TSH (Fig. 8A). In keeping with these data, the inhibitory effects of TSH on osteoclast gene markers in the ODF cultured ES cells was partly neutralized by recombinant TNFα (Fig. 8B). These data supported the concept that TSH directly inhibited TNFα expression in osteoclast precursors (8,10), thus reducing osteoclastogenesis.

FIG. 7.

Expression of TNFα in differentiated ES cell cultures. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of TNFα mRNA levels in the cultured cells with ODFs in the presence of TSH and MS1 antibody. Values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression. The results are representative of three independent experiments. Significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.01) comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH or MS1 antibody. (B) Total lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for detection of the TNFα isoforms. TNFα expression was decreased by the presence of TSH or MS1 antibody (inset). Densitometric evaluation of both isoforms in this immunoblot also illustrates the inhibition of TNFα (*p < 0.01). TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

FIG. 8.

Modulation of TNF and osteoclast markers. (A) Undifferentiated ES cells were cultured with four ODFs for 12 days and stimulated with TNFα (30 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of increasing doses of TSH for 2 hours. TNFα expression levels were measured by real-time qPCR. TSH decreased TNFα expression levels induced by recombinant TNFα in a dose-dependent manner. Values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression. The results are representative of three independent sets of similar experiments. *p < 0.01 comparing between ODFs treatment in the presence of TNFα and ODFs treatment in the presence of TNFα and TSH. (B) Attenuation of osteoclast markers by recombinant TNFα in the presence of TSH. mRNA expression levels were analyzed by real-time qPCR after 12 days osteoclast differentiation from ES cells with ODFs in presence of TSH alone or TNFα (30 ng/mL) plus TSH. As indicated in this graph, TNFα reversed the suppression of osteoclast markers induced by TSH alone. Values were normalized to GAPDH RNA expression. The results are representative of at least three independent sets of similar experiments. The p-value comparing ODFs treatment versus ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH (*p < 0.01) or ODFs treatment in the presence of TSH and recombinant TNFα (^p < 0.01).

Discussion

The TSHR is not restricted to the thyroid gland but is expressed in a variety of tissues, including bone cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes (24). Several nontraditional biological roles for the TSHR have been hypothesized, such as those involving the production of nitric oxide (25), the stimulation of smooth muscle cells (26) and angiogenesis (27), and the regulation of adipogenesis (28). We recently described TSHR expression in osteoclasts and osteoblasts and found that TSH can modulate bone remodeling independent of thyroid hormones (8,10). Indeed, reduced expression of the TSHR was associated with the development of osteoporosis with evidence of enhanced osteoclast differentiation in experimental animals lacking the TSHR (8,10). In parallel studies, with mature murine osteoclast preparations, we found that TSH directly inhibited TNFα production, and attenuated the induction of TNFα expression by interleukin-1, TNFα, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand. TSH also suppressed osteoclast formation from murine macrophages and RAW-C3 cells (8,10). The suppression was most profound in cells that overexpressed the TSHR and was ligand-independent when a consitutively overactive TSHR was transfected into primary bone cells. While clearly thyroid hormone, in the form of T3, activates osteoclast function (7), the TSHR, and by implication TSH, must have a modulating influence despite views to the contrary (9). Further, in direct contrast with a previous report (9) we also demonstrated a potential role for the stimulating TSHR-Abs found in patients with Graves' disease. The osteoporosis found in some women with Graves' disease recovers to a great extent when the patients are rendered euthyroid (1,14), but whether TSHR-Abs are able to protect bone from excess thyroid hormone during the thyrotoxicosis stage remains to be demonstrated. Our observations, however, suggest that the presence of TSHR-Abs may have an important role in this response.

In the present study, we first established a culture system to induce osteoclast differentiation from ES cells using the addition of four ODFs, M-CSF, RANK-L, 25(OH)2D3, and Dex (15). Using this protocol we achieved a ∼10.0% differentiation of ES cells into calcitonin receptor expressing cells, which can be considered preosteoclasts and osteoclasts. Critical levels of Oct4, Sox2, and REX1 expression, which are required to sustain stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency, were appropriately downregulated in the ES cells after differentiation, whereas the number of TRAP-positive cells and the number of bone pits produced were significantly increased. However, with the addition of TSH to the cultures, the number of TRAP-positive cells fell by 40%–50% and the transcription of osteoclast gene markers, including CTR, TRAP, CTSK, MMP-9, and CA2, was also markedly decreased. These results not only supported the earlier observations that TSH negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis but also implied that this influence may occur very early in development and explaining the TSHR−/+ haploinsufficient mouse phenotype (8,10). The fact that stimulating TSHR-mAbs were able to mimic the effects of TSH reinforced the fact that it was the TSHR signaling that was responsible for the effects on these osteoclasts and further evidenced the likelihood that such antibodies influence the bone response to hyperthyroidism in Graves' disease.

Osteoclast differentiation is regulated by the RANK/RANKL/OPG ligand-receptor system (29). The binding of RANK and RANKL induces differentiation of osteoclasts. OPG, a decoy receptor for RANKL, originating from osteoblasts, acts as an antagonist of RANKL. Thus, osteoclast differentiation appears to be mainly controlled by the ratio of RANKL:OPG. Interestingly, in the human thyroid follicular cancer cell line XTC and in primary human thyroid follicular cells, OPG mRNA levels and protein secretion have previously been reported to be upregulated by TSH (30). In the ES cell system described here, the OPG levels were also significantly increased in response to TSH stimulation in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a direct interaction of TSH with osteobast-like cells differentiating in the cultures. Neutralization of OPG clearly attenuated the TSH induced inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Thus, TSH decreased osteoclast differentiation from ES cells partially via an increase in the OPG levels within the cultures.

In contrast to OPG, TNFα is a cytokine that is well known to enhance osteoclast formation (22,31). In earlier studies using matured primary osteoclasts, we found that TSH inhibited TNFα production and attenuated the induction of TNFα expression (8,10). Similarly, in the current experiments employing ES cells, TSH decreased the TNFα mRNA levels in a dose-dependent manner and consistent with the decreased protein level. Further, the well reported effect of TNFα on inducing its own TNFα mRNA expression was also significantly attenuated by TSH. These data supported the concept that TSH decreased osteoclasteogenesis from ES cells, in part, by inhibiting TNFα expression (8,10) in addition to enhancing OPG production in the culture. While the signaling pathways employed by TSH to influence OPG and TNFα are uncertain, we do know that TSH can activate protein kinase A and cyclic AMP production in ES cells (32,33) and we could speculate a cross signaling mechanism for this activation.

The present study demonstrated that ES cells can be used as a powerful tool to study the early development of osteoclasts and can also help evaluate the effects of TSH and TSHR-Abs on the differentiation of osteoclasts. The present data also suggest that the bone defect in the TSHR KO mouse is most likely the result of abnormal bone remodeling starting very early in development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fred Yao for technical assistance and Drs. Xiaoming Yin and Annie Baliram for ongoing discussions and support. These studies were supported in part by DK069713, DK052464, and DK080459 from the National Institutes of Health, the Veteran Affairs Merit Award program, and the David Owen Segal Endowment.

Disclosure Statement

T.F.D. is a member of the Board of the Kronus Corporation, which distributes thyroid diagnostic kits. R.M., S.M., R.L., and M.Z. have nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Ross DS. Hyperthyroidism, thyroid hormone therapy, and bone. Thyroid. 1994;4:319–326. doi: 10.1089/thy.1994.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biondi B. Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:76–131. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaidi M. Davies TF. Zallone A. Blair HC. Iqbal J. Moonga SS. Mechanick J. Sun L. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid hormones, and bone loss. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim BJ. Lee SH. Bae SJ. Kim HK. Choe JW. Kim HY. Koh JM. Kim GS. The association between serum thyrotropin (TSH) levels and bone mineral density in healthy euthyroid men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73:396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazziotti G. Porcelli T. Patelli I. Vescovi PP. Giustina A. Serum TSH values and risk of vertebral fractures in euthyroid post-menopausal women with low bone mineral density. Bone. 2010;46:747–751. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mundy GR. Shapiro JL. Bandelin JG. Canalis EM. Raisz LG. Direct stimulation of bone resorption by thyroid hormones. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:529–534. doi: 10.1172/JCI108497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogakos AI. Duncan Bassett JH. Williams GR. Thyroid and bone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe E. Marians RC. Yu W. Wu XB. Ando T. Li Y. Iqbal J. Eldeiry L. Rajendren G. Blair HC. Davies TF. Zaidi M. TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell. 2003;115:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett JH. Williams AJ. Murphy E. Boyde A. Howell PG. Swinhoe R. Archanco M. Flamant F. Samarut J. Costagliola S. Vassart G. Weiss RE. A lack of thyroid hormones rather than excess thyrotropin causes abnormal skeletal development in hypothyroidism. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:501–512. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hase H. Ando T. Eldeiry L. Brebene A. Peng Y. Liu L. Amano H. Davies TF. Sun L. Zaidi M. Abe E. TNFalpha mediates the skeletal effects of thyroid-stimulating hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12849–12854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600427103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampath TK. Simic P. Sendak R. Draca N. Bowe AE. O'Brien S. Schiavi SC. McPherson JM. Vukicevic S. Thyroid-stimulating hormone restores bone volume, microarchitecture, and strength in aged ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:849–859. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L. Vukicevic S. Baliram R. Yang G. Sendak R. McPherson J. Zhu LL. Iqbal J. Latif R. Natrajan A. Arabi A. Yamoah K. Moonga BS. Gabet Y. Davies TF. Bab I. Abe E. Sampath K. Zaidi M. Intermittent recombinant TSH injections prevent ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4289–4294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heemstra KA. Hamdy NA. Romijn JA. Smit JW. The effects of thyrotropin-suppressive therapy on bone metabolism in patients with well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2006;16:583–591. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belsing TZ. Tofteng C. Langdahl BL. Charles P. Feldt-Rasmussen U. Can bone loss be reversed by antithyroid drug therapy in premenopausal women with Graves' disease? Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamane T. Kunisada T. Yamazaki H. Nakano T. Orkin SH. Hayashi SI. Sequential requirements for SCL/tal-1, GATA-2, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and osteoclast differentiation factor/osteoprotegerin ligand in osteoclast development. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:833–840. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando T. Latif R. Pritsker A. Moran T. Nagayama Y. Davies TF. A monoclonal thyroid-stimulating antibody. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1667–1674. doi: 10.1172/JCI16991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders J. Jeffreys J. Depraetere H. Evans M. Richards T. Kiddie A. Brereton K. Premawardhana LD. Chirgadze DY. Núñez Miguel R. Blundell TL. Furmaniak J. Rees Smith B. Characteristics of a human monoclonal autoantibody to the thyrotropin receptor: sequence structure and function. Thyroid. 2004;14:560–570. doi: 10.1089/1050725041692918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morshed SA. Latif R. Davies TF. Characterization of thyrotropin receptor antibody-induced signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2009;150:519–529. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacey DL. Timms E. Tan HL. Kelley MJ. Dunstan CR. Burgess T. Elliott R. Colombero A. Elliott G. Scully S. Hsu H. Sullivan J. Hawkins N. Davy E. Capparelli C. Eli A. Qian YX. Kaufman S. Sarosi I. Shalhoub V. Senaldi G. Guo J. Delaney J. Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasuda H. Shima N. Nakagawa N. Yamaguchi K. Kinosaki M. Mochizuki S. Tomoyasu A. Yano K. Goto M. Murakami A. Tsuda E. Morinaga T. Higashio K. Udagawa N. Takahashi N. Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azuma Y. Kaji K. Katogi R. Takeshita S. Kudo A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces differentiation of and bone resorption by osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4858–4864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi K. Takahashi N. Jimi E. Udagawa N. Takami M. Kotake S. Nakagawa N. Kinosaki M. Yamaguchi K. Shima N. Yasuda H. Morinaga T. Higashio K. Martin TJ. Suda T. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL-RANK interaction. J Exp Med. 2000;191:275–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam J. Takeshita S. Barker JE. Kanagawa O. Ross FP. Teitelbaum SL. TNF-alpha induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1481–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies TF. Ando T. Lin RY. Tomer Y. Latif R. Thyrotropin receptor-associated diseases: from adenomata to Graves disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1972–1983. doi: 10.1172/JCI26031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giusti M. Valenti S. Guazzini B. Molinari E. Cavallero D. Augeri C. Minuto F. Circulating nitric oxide is modulated by recombinant human TSH administration during monitoring of thyroid cancer remnant. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:1192–1197. doi: 10.1007/BF03349156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sellitti DF. Dennison D. Akamizu T. Doi SQ. Kohn LD. Koshiyama H. Thyrotropin regulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Thyroid. 2000;10:219–225. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein M. Brunaud L. Muresan M. Barbé F. Marie B. Sapin R. Vignaud JM. Chatelin J. Angioï-Duprez K. Zarnegar R. Weryha G. Duprez A. Recombinant human thyrotropin stimulates thyroid angiogenesis in vivo. Thyroid. 2006;16:531–536. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antunes TT. Gagnon A. Chen B. Pacini F. Smith TJ. Sorisky A. Interleukin-6 release from human abdominal adipose cells is regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone: effect of adipocyte differentiation and anatomic depot. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1140–E1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00516.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vega D. Maalouf NM. Sakhaee K. CLINICAL Review #: the role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB (RANK)/RANK ligand/osteoprotegerin: clinical implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4514–4521. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofbauer LC. Kluger S. Kuhne CA. Dunstan CR. Burchert A. Schoppet M. Zielke A. Heufelder AE. Detection and characterization of RANK ligand and osteoprotegerin in the thyroid gland. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86:642–650. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim N. Kadono Y. Takami M. Lee J. Lee SH. Okada F. Kim JH. Kobayashi T. Odgren PR. Nakano H. Yeh WC. Lee SK. Lorenzo JA. Choi Y. Osteoclast differentiation independent of the TRANCE-RANK-TRAF6 axis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:589–595. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arufe MC. Lu M. Kubo A. Keller G. Davies TF. Lin RY. Directed differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into thyroid follicular cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3007–3015. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma R. Latif R. Davies TF. Thyrotropin-independent induction of thyroid endoderm from embryonic stem cells by activin A. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1970–1975. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]