Abstract

Cancer is a highly complex disease due to the disruption of tissue architecture. Thus, tissues, and not individual cells, are the proper level of observation for the study of carcinogenesis. This paradigm shift from a reductionist approach to a systems biology approach is long overdue. Indeed, cell phenotypes are emergent modes arising through collective non-linear interactions among different cellular and microenvironmental components, generally described by “phase space diagrams”, where stable states (attractors) are embedded into a landscape model. Within this framework, cell states and cell transitions are generally conceived as mainly specified by gene-regulatory networks. However, the system s dynamics is not reducible to the integrated functioning of the genome-proteome network alone; the epithelia-stroma interacting system must be taken into consideration in order to give a more comprehensive picture. Given that cell shape represents the spatial geometric configuration acquired as a result of the integrated set of cellular and environmental cues, we posit that fractal-shape parameters represent “omics descriptors of the epithelium-stroma system. Within this framework, function appears to follow form, and not the other way around.

Keywords: system biology, cancer, fractal analysis, complexity, carcinogenesis, non linear dynamics

Introduction

Hornberg et al.1, have stated that “cancer is […] a Systems Biology Disease. Indeed, progress in cancer research towards cancer therapy may develop faster if cancer is not researched only in terms of molecular biology, but rather in terms of Systems Biology”. A Systems Biology (SB) approach requires a “systematic integration of data” that is provided by high-throughput techniques at a rate inconceivable until few years ago2. Under this heading, adopting an “SB framework” is nothing more than relying on an efficient data base of the already known and stored immense corpus of molecular details about cancer biology. Admittedly, the relevance of this corpus for carcinogenesis is rather controversial, to say the least. An SB approach is not merely a matter of computational tools; it requires, instead, a radical shift from an old into a new paradigm.3 This transition emerges “from the ashes of genetic reductionism”4, fostered by the awareness that “the key obstacle to future medicine is the conflict between the reality of complexity and a reductionistic approach”5. In fact, even partisans of the “reductionistic approach”, now recognize that not only the classic carcinogenic paradigm, but also the scientific methodology behind it, “are no more maintainable.”6,7 Herein, we sketch a general frame for a systemic cancer appreciation, first, by giving a reliable and operational definition of “system,” and second, by reaching in depth into the relevant features of cancer as a system . Finally, we highlight the relevance of the shape of cells and tissues as studied by fractal analysis in the construction of a reliable phase space for cancer development.

The System

Modern biology does not explicitly takes into account the problem of many levels of observation, thus ignoring the possibility of considering a biological entity as a “system”. Moreover, after the initial widespread, positive reception to the Central Dogma of Biology, the paradigm of gene-centered biology has been “illegitimately extended as a paradigm of life”8, thus yielding confusion between different hierarchical organization levels: “Now we are mixing our levels in biology and it doesn t work”8.

Cancer research has focused on molecular entities (genes, enzymatic reactions, intracellular pathways), under the implicit assumption that molecules have their proper autonomy and behave like a “biological system”, i.e., a group of entities that work together to perform a certain task. However, “a system is not just an assembly of genes and proteins [and] its properties cannot be fully understood merely by drawing diagrams of their interconnections”8. From a thermodynamic point of view, any part of the universe could be legitimately considered a “system”, provided its borders can be defined in a sufficiently reliable way. Nevertheless, when referring to a “system” in biology, focusing only on thermodynamics can be misleading. Thermodynamics typically refer to a macroscopic view of the system at hand defined by macro-variables (i.e., temperature, pressure, volume) that allow for a reliable prediction of relevant system s features. This reliability comes from the statistics over a huge number of particles without the need of explicitly taking into consideration the correlative structure generated by the among particles, i.e., without any particular concern on the shape of the system at hand.

In biological systems, shape plays a crucial role and thus, it becomes imperative to focus at the so called mesoscopic level of observation9, where the interaction among elements of the system take place and where shape is generated. In architecture, the mesoscopic level is located at the level of the arch, while a brick is microscopic and the entire building is the macrolevel. By comparing the form of the arches, one can discriminate between a Romanesque and a Gothic cathedral, while this task is impossible to accomplish by either an analysis of the bricks or of the general plan of the construction. Therefore, for a proper system-level understanding - the approach advocated in systems biology - a shift in our notion of “what to look for” is required.

Reductionism derived macroscopic behaviour from microscopic details “obeying a theory of everything”10. As pointed out by Strohman “it is the mesoscopic organization of matter (living or dead) that harbours as yet undiscovered principles lying behind emergent features”11. Within this framework, the genome does not “explain anything”, even if one were to believe that it represents the digital core of information 12 on which higher-level system properties are thought to be “mechanistically-linked”13. Confusion results from conflating the two gene-based properties, i.e., protein-coding functions and involvement in hereditary character transmission14. Nevertheless, this does not actually imply the existence of a privileged level of causality: there is no one-to-one correspondence between genes or proteins and higher-level biological functions. As outlined by Noble, it is a prejudice what inclines us to give a causal priority to a lower-level (molecular) and “the concept of level in biology is itself metaphorical”15. Clearly, this latter quote provides a different definition of genome that no longer can be interpreted as the “molecular hardware” of a “genetic program”16. The newly formulated “middle way” searches for rules of self organization appropriate to the mesoscopic domain, in order to find useful approximations to how things work. Such approximations have led to major insights in physics and even in biology16.

This mesoscopic level must include cells and their microenvironment (stromal cells and extracellular matrix components) where carcinogenesis takes place17. In addition to the upward causation prevalent in reductionism, downward causation should also be included. The mesoscopic level is where organizational principles act on the elementary biological units that will become altered, or constrained, by both their mutual interaction and the interaction with the surrounding environment. In this way and in this place is where general organization behaviour emerges and where we expect to meet the elusive concept of complexity.

Complex Systems

According to Prigogine18, a complex system should 1) possess information; 2) be neither strictly ordered (like a crystal) nor fully disordered (like a gas); 3) be thermodynamically open, meaning that it deals with non-linear dynamics; 4) displays emergent collective properties (different from those of the component sub-systems); and 5) have a history, meaning that the present behaviour of the system is in part determined by its past behaviour. The information content of a system is based on Shannon s mathematical theory of information19. This theory is based on the statistical probability of occurrence of the different discrete instances (states) of a system. In order to apply such a paradigm we need to know a priori the entire set of possible states; this is the reason why the mathematical theory of information was successfully applied to biopolymers, where the instantaneous states of the system are fully known (nucleotides for DNA, aminoacid residues for protein sequences). By analogy, total information in the living cell was often identified mistakenly with genetic information; genome information content could hardly be representative of the overall cell information content. For instance, differences between genome sequences of humans and mice are not correlated with the differences of form and function between them20. Moreover, there are many examples in which no or little correlation exists between genetic and morphological complexity, pointing out that information relevant for function could not be located solely at the genomic level21. This means that, broadly speaking, the informational content of a living cell is something different than that of its genome22. A telling example of this mistaken view is exemplified by the multiple dog phenotypes that share a mostly identical genome23.

In complex systems, information is expressed as negative entropy. Attempts to give an operational definition of negative entropy and anti-entropy24 as a measure of complexity were made. Moreover, because classical Shannon s communication theory is not ideally suited for describing what is meant by biological network information , numerous papers evaluate the information content of several kinds of networks25,26 with the aim of obtaining a compelling definition of complexity . Indeed, while complexity measures abound, their relationship to biology are not always clear. Moreover, some theoretical approaches are hardly of practical interest, given that parameters and variables thought to measure complexity are difficult to compute and to be translated into biologically meaningful features27. In addition, a complex system can display several kinds of complexity that cannot be expressed by the classic and generic notion of entropy28.

A suitable, but not exhaustive, conceptualisation of complexity should be addressed in terms of the required information for system description, as proposed by Chaitin and Kolmogorov 29. Accordingly, a system could be considered “maximally complex when the rate of change of the irreducible amount of information required describing that system with respect to some parameter or parameter set is an extremum. This means that the absolute value of the slope of the amount of irreducible information required to describe the system versus some parameters reaches a maximum […] when the system is maximally complex”30. Such a definition fits well with one of the measures of complexity we shall consider, i.e., the fractal dimension of cell shape, while at the same time allows to directly tackle the problem of multiple hierarchical levels and non-linearities.

Attractors and phase-space diagram

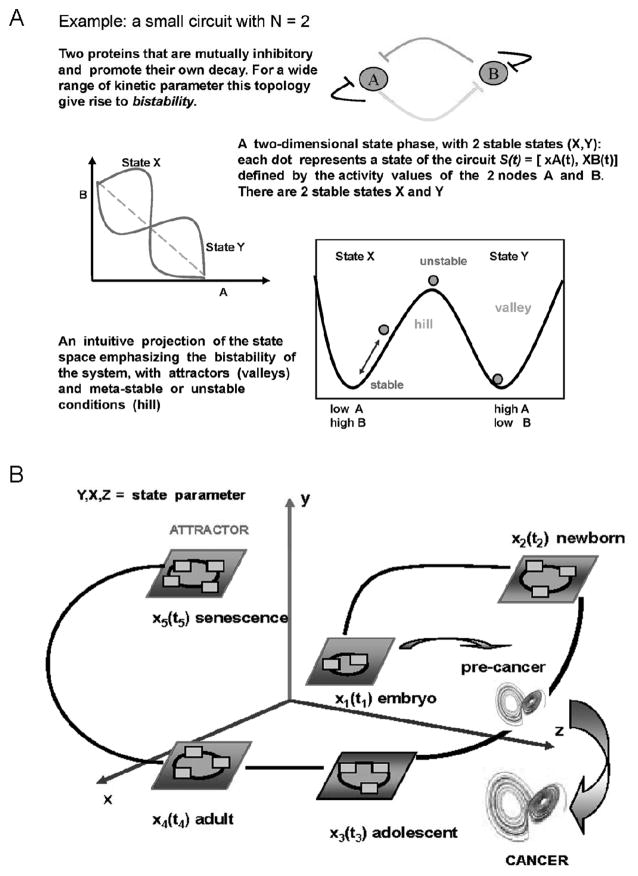

Regulation of cell functions can be thought of as physically and topologically structured molecular interactions and physical forces located at different hierarchical levels. In dissipative systems, such as living organisms, the overall system behaves according to a non-linear dynamics31. The dynamics of such a system is the concerted change in the levels of xi(t) [ the value of the node i ] for all the nodes i of the network (a metabolomic or genomic network) and can be represented by the N-dimensional state vector: S(t) = [ x1(t), x2(t),….xN(t)]. While the topology represents the network by a graph, for a network with N nodes, the dynamics can be better described in the Phase Space (with N-dimension or degree of freedom) in which S(t) changes its position along the time coordinate t as defined by its components [ x1(t), x2(t),….xN(t)]. The mathematical formalism of the phase space diagram for dissipative systems is described by the theory of dynamical non-equilibrium systems32. As proposed by Kauffman33, the Phase Space describes a landscape characterized by attractors (“valleys”) –surrounded by basins –separated by “hills”: the difference in the behavioral potential between cells lies in their position on the landscape and the associated accessibility to attractors (Fig. 1). In this view, cell fate regulation is based on selection between pre-existing, limited, intrinsically robust fates. It must be stressed that the special state vector S*(t) is a stationary state in which there is no net driving force. The trajectories emanating from the neighbourhood are “attracted” and converge to S*(t). This stable attractor state is robust to many perturbations: “attractors” are, indeed, self-organizing structures and can “capture” gene expression profiles associated with cell fates34.

Figure 1.

A discrete finite number of attractor classes do exist. Generally, strange attractors (i.e., dynamics that do not follow a simple periodic trajectory) arise from non-linear dynamical systems. The phenotypic traits of the organism are embedded into the dynamic attractors of its underlying regulatory network.35,36 Functional states depicted as attractors have been conceived as mainly specified by the gene-regulatory network34. However, “the stability of functional states clearly also depends on external cues”37. Thus, system s dynamics in the phase space cannot be “reduced” either to a genetic wiring diagram or, even to the integrated functioning of a genome-proteome-metabolome network. Additional influences –i.e., those of the intracellular topology that makes the chemical reactions of the “networks” possible, as well as those resulting from parenchyma-stroma interacting system –must be taken into consideration in order to give a more reliable definition of attractor. This revised conceptualisation of “attractors” could fit numerous observations on tissue dynamics, the existence of different dynamical regimens, as well as the transitions between them38. Moreover, this hierarchical organization creates downward causation39 complementing the better known upward causation, and thereby shaping the complex behaviour of the system40.

Shape as a measure of complexity

Like any other hierarchical construct, biological entities are thought to potentially adopt an undefined possibility of configurations (“forms”) inside the realm of a common general frame. However, only a limited number of them is actually observed. In the case of protein structures, the number of folds is much lower than that expected when referring to the transfinite number of possible dispositions of N residues in space; different sequences may give rise to the same fold. This implies some sort of energy minimization drastically constraining the number of allowable stable states41, with the consequent onset of preferred stable states (attractors, in dynamic terms). Given that protein folding results from the non-linear interactions between internal (aminoacids sequence) as well as microenvironmental constraints, the resulting configuration can be considered as the integrated output of such complex and dynamic interplay taking place at the mesoscopic level.

Therefore, shape descriptors could be reliably used as overall indicators of macrostates. Indeed, cancer diagnosis as well as that of other diseases has been routinely made by looking at the cell and tissue shapes elicited by those pathological entities42,43. Moreover, quantitative measures of shape could be considered in depicting the phase space of choice, like tissue organization and structure. The shape of cells and the structures they form is the consequence of physical forces generated in the cytoskeleton as well as in the extracellular matrix. Shape, in reflecting cytoskeleton organization, is linked to the repertoire of metabolic events, which result from the right ordering in space of the enzymes catalysing specific pathways. Physical forces (like microgravity) induce dramatic changes in gene expression and alter cellular shape.44,45

Despite limited knowledge about how living cells “sense” mechanical stresses, evidence suggests that relevant modifications in the expression of thousands of genes and in the activity of enzymatic reactions can be quickly elicited by modifications in cell shape. Changes in the balance of forces that are transmitted across trans-membrane adhesion receptors that link the cytoskeleton to other cells and to the extracellular matrix influence cell morphology and subsequently induce alterations in intracellular biochemical processes46. In this context, it is unlikely that the observed changes in cell phenotype and genome functions could be ascribed to a single (or a few) signalling pathways operating in isolation. Equally striking, the “dramatic” twisting of the tension-dependent form of (intracellular) architecture promptly leads to an overall modification in both the cell shape and of cytoskeleton-linked biochemical pathways47. Cells appear to be literally “hard-wired” so that they can filter the same set of inputs to produce different outputs, and this mechanism is largely controlled through physical distortion of plasma membrane adhesion receptors that transmit stress to the cytoskeleton. Thus, the switch between different cell fates could be considered dependent on cell-distortion48. Local geometric control of cell functions may hence represent a fundamental mechanism for developmental regulation within the tissue microenvironment. Yet, a compelling theory explaining the link between shape and biochemical activity is still lacking. On the one hand, this is partly due to the limited knowledge about how biochemical reactions are associated to the cytoskeleton (i.e., the internal topology of structures-linked reactions), and, on the other, to a lack of a standardized and a widely accepted measure of cell shape complexity. A quantitative method that lends itself particularly useful for characterizing complex irregular structures is fractal analysis.

Although classical Euclidean geometry works well to describe properties of regular smooth-shaped objects such as circles or squares by using measures such as the length of the object's perimeter, these Euclidean descriptions are inadequate for complex irregular-shaped objects that occur in nature (e.g., clouds, coastlines, and biological structures). These “non-Euclidean” objects are better described by fractal geometry, which has the ability to quantify the irregularity and complexity of objects with a measurable value called the fractal dimension.

Fractal dimension differs from our intuitive notion of dimension in that it can be a non-integer value and the more irregular and complex an object is, the higher its fractal dimension49. Fractal analysis can lead to a remarkable improvement in both cyto-histological and radiographic diagnostic accuracy50,51. Applications of fractal measures to pathology and oncology52 suggest that fractal analysis provides reliable and unsuspected information53,54. For instance, fractal analysis helped in discriminating benign from malignant neoplasms55, low from high grade tumours56; furthermore, fractal studies elucidated some aspects of the complex interplay between cancer cells and stroma by suggesting that tumor vascular architecture is determined by heterogeneity in the cellular interaction with the extracellular matrix rather than by simple gradients of diffusible angiogenic factors57. Moreover, fractal analysis of the interface between cancer and normal tissues helps in understanding how cell detachment from the primary mass and infiltration into adjacent tissue occurs through a non-mutational mechanism 58,59.

A correlation between the fractal dimensions of the epithelia/stroma interface in the oral cavity with the evolving lesions (from dysplasia to invasive carcinoma) was linked to increases in the irregularity of the surface and of the fractal number (from 1.0 of normal epithelium to 1.62 for invasive tumour).60 Also, both the global and local fractal dimension of the epithelium-stroma interface increased from normal through pre-malignant to malignant oral epithelium61 implying that the involvement of the epithelium-stroma interface is not merely a consequence of tumor development, but instead is an intrinsic feature of the carcinogenic process. On the contrary, P19 carcinoma cells undergoing differentiation when treated with all-trans retinoic acid, shows a significant reduction in their fractal dimension62.

Collectively, these results highlight the relevance of shape-phenotype relationships that over three decades ago motivated Folkman and Moscona63 to ask, “how important shape is”60? An answer to this question largely remains unknown. However, Ingber claimed that “the importance of cell shape appears to be that it represents a visual manifestation of an underlying balance of mechanical forces that in turn convey critical regulatory information to the cell”64. Thus, cell distortion influences cytoskeleton function and a cell s adhesion to the ECM. Cell shape and cytoskeletal structure appear to be tightly coupled to cell proliferation.48 In this way, tissue structure limits the constitutive ability of cells to proliferate65. Within this framework it seems as if “function follows form, and not the other way around”66.

The biophysical bases of fractals

Mandelbrot67 introduced the term 'fractal' (from the Latin fractus, meaning 'broken') to characterize spatial or temporal phenomena that are continuous but not differentiable. In fractal analysis, the Euclidean concept of 'length' is viewed as a process. This process is characterized by a constant parameter D known as the fractal (or fractional) dimension. The fractal dimension has a thermodynamic meaning, and can be viewed as an intensive measure68 of the “overall” (morphologic) complexity69. Therefore, together with two or more independent variables, this would enable the construction of a diagram of phases, like that relying on temperature, pressure and volume for gas/liquid/solid phase-transitions. In fact, according to the Bendixon-Poincaré theorem, if a dynamic process possesses a limit cycle, (i.e., an attractor) then that attractor has fractal dimension. And vice versa, the existence of fractal dimension for a given dynamic process denotes that the process has been measured at its attractor70. In non-equilibrium systems, the fractal attractor is a common feature because of the dissipative character of these systems. The information dimension can then be used to determine the number of undamped dynamical variables which are active in the motion of the system; this means that dimension is something related to the number of degrees of freedom of the system. Although there may be many nominal degrees of freedom available, the physics of the system may organize the motion into only a few effective degrees of freedom. This collective behaviour is often termed self-organization and it arises in dissipative dynamic systems whose post-transient behaviour involves fewer degrees of freedom than are nominally available. The system is attracted to a lower-dimensional phase space, and the dimension of this reduced phase space represents the number of active degrees of freedom in the self-organized system. A similar trend can be observed during the shift from a morphotype to another in the course of the specialization/differentiation of a cell lineage. A cell type proceeds through a discrete number of morphotypes along its specializing/differentiating pathway, and every morphotype could be considered as a stable steady-state71. In a similar way, morphologic characterization of a cell population by means of fractal analysis could provide at least an independent variable thought to be used to construct a (measurable) space phase of the evolving system, in order to characterize the attractors and the location of bifurcations.

Experimental results: how does a morphogenic field modify cell shape and tumour phenotype?

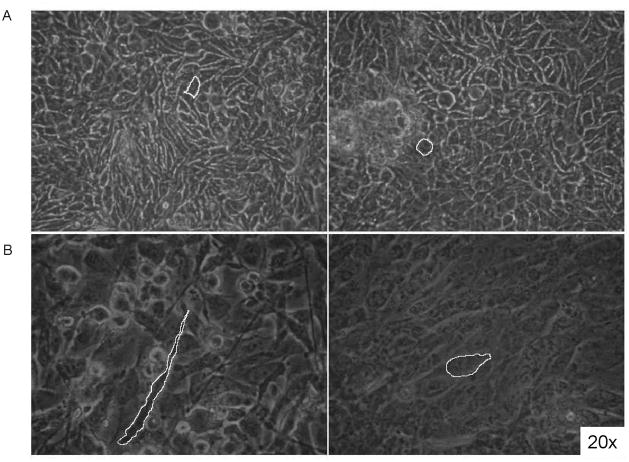

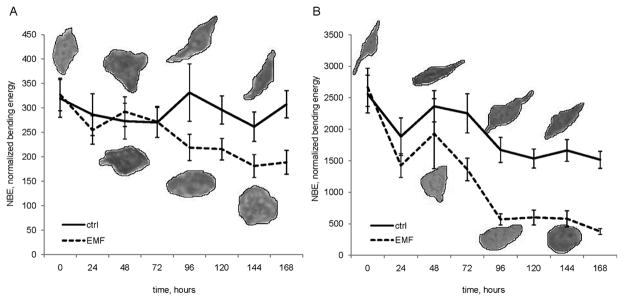

Mammary cancer epithelial cells form normal mammary ducts when transplanted into a normal mammary gland stroma72. Similarly, human cancer cells exposed to a microenvironment of normal embryonic cells revert toward a non-malignant phenotype73,74,75. Those cancer cells underwent a complex transition, involving morphologic as well as metabolic and functional modifications. Breast cancer cells growing in an in culture maternal-like morphogenetic field (EMF) progressively undergo dramatic changes in both shape and metabolome reversion76. After 48 h, membrane profiles of breast cancer cells growing in EMF change evolving into a more rounded shape, loosing spindle and invasive protrusions (Fig. 2). Fractal analysis was carried out by calculating the Normalized Bending Energy (NBE) of cell membranes (Fig. 3). NBE characterizes shape by expressing the amount of energy needed to transform the specific shape under analysis into its lowest energy state (i.e. a circle)77. The “curvegram” obtained by using digital signal processing techniques gives a multi-scale representation of the curvature. As such, the bending energy provides a resource for translation and rotation-invariant shape classification, as well as a means of deriving quantitative information about the complexity of the shapes being investigated78. For biological shapes, NBE provides a particularly meaningful physical interpretation in terms of the energy that has to be applied in order to produce or modify specific objects79.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Epithelial cancer cells exhibit high NBE values, while EMF treatment induces a dramatic two-fold reduction on those levels. NBE is inversely correlated with the surface tension, and surface tensions are reflective of intercellular adhesive intensities80 from which we inferred that EMF-treatment reducing Bending Energy increases the intercellular adhesion forces. This is noteworthy because surface tension influences both embryonic cell behaviours and metastatic spreading of cancer cells81.82. As expected, the bending energy transition experienced by cells under treatment with EMF is associated to a significant reduction in fractal dimension of their cytoplasmic shape (from 1.6 to 1.3). Thus, reversion of tumour shape into a more “physiologic” fractal-dimension implies reduced morphologic instability and increased connectivity between cells. As a consequence of cell shape “normalization”, breast cancer cells exposed to EMF form organized structures (ducts and mammary acini), reactivate signaling pathways and they recover both tight and gap-junctions.83 In contrast, current cytotoxic anticancer treatments induce a significant increase in cell shape fractal dimension and “may unwittingly contribute to tumour morphologic instability and consequent tissue invasion”84. Mild chemotherapeutic regimens do not modify tumour fractal dimension whereas intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy increases fractal values and thus, enhances tissue disorder favouring more malignant phenotypes85.

β-catenin plays critical roles in morphogenesis and in human cancer86 where it is mainly detectable in the nucleus acting as a transcription factor. In addition, E-cadherin is a negative regulator of β-catenin signalling by stabilising the latter beneath the plasma membrane and thereby sequestering it from the nucleus. Therefore, β-catenin s functions are strictly linked to its intracellular position and this topological information can be incorporated into fractal analysis by means of the Moran Index (MI)87. Confocal microscopy data while correlating spatial β-catenin distribution versus the inner plasma membrane showed a MI ranging from +1 to -1 with 0 corresponding to the absence of a spatial correlation and -1 to maximum dispersion. In EMF-treated epithelial cancer cells, ß-catenin distribution was progressively modified evolving from a mean MI value of −0.7 to a mean M.I. value of +0.5 suggesting that, after cell shape normalization, β-catenin moves from the nucleus toward the plasma membrane. Meanwhile, in control cells, β-catenin presents an almost totally disorganized spatial distribution. Concomitantly, in EMF-treated epithelial cancer cells, one can observe a significant increase in E-cadherin release. These results –shape modification and E-cadherin/β-catenin redistribution -- collectively suggest that EMF-treated cells undergo a significant transition from a Warburg-like metabolism towards an oxidative pathway. Glycolytic fluxes were reduced with a parallel decrease in lactate, glutathione, glutamine and other compounds. Citrate and de-novo lipogenesis are, in turn, inhibited. In EMF-treated cells, glutaminolysis does not correlate with a simultaneous increase in lactate (as expected when the difference between control and treated cell metabolism should be confined to a mere diversification of energy sources for treated cells), nor with an increase in fatty acid synthesis (as expected when de novo cell membrane production is required to sustain cell proliferation). Keeping in mind that proliferation is inhibited in EMF-treated cells, these results suggest that glutaminolysis increases cannot be explained by proliferative needs: this implies that the treated cells devote a higher portion of chemical energy to a different anabolic work. Indeed, glutamine is preferentially transformed into proteins and does not appear as lactate.

These data outline how cancer metabolism is driven by the morphogenetic field toward a less dissipative profile. This pattern is mirrored by the changes observed in shape profile. Therefore, fractal dimension emphasizes the neglected link between cell morphology and thermodynamics. According to the Prigogine-Wiame theory of development88, during carcinogenesis, a living system constitutively deviates from a steady state trajectory that is accompanied by an increase in the system dissipation function (Ψ) at the expense of coupled processes in other parts of the organism, where Ψ = q0 + qgl (meaning, respectively, q0 oxygen consumption and qgl glycolysis intensity). NBE represents a “dissipative” form of energy; this effect is mirrored by metabolomic data showing a significant reduction in glycolytic activity (in the presence of unchanged values of oxygen consumption). It follows that in our experimental conditions, Ψ decreased significantly until a stable state was attained, that is characterized by a minimum in the rate of energy dissipation (principle of minimum energy dissipation) recorded at both morphological and metabolic level of observation89. This behaviour is exactly the opposite of what is expected in proliferating cancer cells, as experimentally observed in tumour controls.

Conclusion

Cell phenotypes represent emergent behaviours that arise through collective interactions among different cellular and microenvironmental components90. These behaviours are driven by a non-linear dynamics. Several approaches have been proposed to give a reliable answer to the question, how distinct cell fates emerge? The detailed knowledge of the wiring diagram of the genetic regulatory network and their transcriptome has been insufficient to predict the dynamic landscape of the biological system. On the other hand, modifications of cell shape results in distinct patterns of gene expression91. If shape is considered as an intensive system property, i.e., that it requires translating it from a qualitative to a quantitative value by means of fractal analysis, then the behaviour of the system could be represented by a phase-space diagram. Transitions from one phenotype to another are reminiscent of phase transitions observed in physical systems. The description of such transitions could be obtained by a set of morphological, quantitative parameters, like fractal measures. These parameters provide reliable information about system complexity. Thereby, phenotypic cell changes could be described in terms of thermodynamic and informational complexity, according to numerous studies revealing strong correlations between shape change and changes in cellular phenotype92,93,94.

Within this framework one might ask “how can one perturb the malignant phenotype while bringing it to display a non-malignant behaviour?” The answer to this question positions the old, under-explored idea of differentiation therapy in a new light.”95. Indeed, an increasing body of experimental results suggests that cancer can be reversed by both physical as well chemical morphogenetic factors belonging to different embryonic morphogenetic fields. These data have contributed to the “rediscovery” of the “morphogenetic field” as a major protagonist in ontogenic and phylogenic change96. Indeed, in our view, morphogenetic field effects revert cancer phenotypic traits through the induction of dramatic shape changes73. Modification of fractal parameters highlights a parallel change in thermodynamics constraints. Thus, it stands to reason that such modifications might be followed by remarkable changes in cell proliferation patterns, metabolism, as well as tissue differentiating behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from The Parsemus Foundation, the Avon Foundation and the NIH (ES0150182, ES012301 and ES08314).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hornberg JJ, Bruggeman FJ, Westerhoff HV, Lankelma J. Cancer: A Systems Biology disease. BioSystems. 2006;83:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil IG, Hill C. Systems biology for cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:44–48. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000150951.38222.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conti F, Valerio MC, Zbilut JP, Giuliani A. Will systems biology offer new holistic paradigms to life sciences? Syst Synth Biol. 2007;1:161–165. doi: 10.1007/s11693-008-9016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Regenmortel MHV. Biological complexity emerges from the ashes of genetic reductionism. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17:145–148. doi: 10.1002/jmr.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heng HHQ. The conflict between complex systems and reductionism. JAMA. 2008;300(13):1580–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbellini G, Preti C. The evolution of the biomedical paradigm in oncology: implications for cancer tehrapy. In: Colotta F, Mantovani A, editors. Targeted therapies in Cancer. Springer; Basel: 2008. pp. 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A rather negative judgment about the methodological foundations of cancer research was made by Robert Weinberg, who expressed the view that experimental oncologists cultivate the illusion of doing “something meaningful” just because they can manage straightforward experiments to accumulate a huge amount of reproducible data” quoted in Leaft C. Why we’re losing the war on cancer (and how to win it) Fortune. 2004;149(6):76–88.

- 8.Kitano H. Systems Biology : a brief overview. Science. 2002;295:1662–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laughlin RB, Pines D, Schmalian J, Stojkovic BP, Wolynes P. The middle way. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:32–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laughlin RB, Pines D. The Theory of Everything. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:28–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strohman R. Organization becomes cause in the matter. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:575–576. doi: 10.1038/76317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood L, Gala D. The digital code of DNA. Nature. 2003;421:444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature01410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerhoff HV, Palsson BO. The evolution of molecular biology into systems biology. Nature Biotechnol. 2004;22:1249–1252. doi: 10.1038/nbt1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss L. The question of questions: what is a gene? Comments on Rolston and Griffiths & Stotz, Theor Med Bioeth. 2006;27(6):523–34). doi: 10.1007/s11017-006-9021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noble D. Claude Bernard, the first systems biologist, and the future of physiology. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:16–26. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S. Redefining priorities in gene-based drug discovery. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:471–472. doi: 10.1038/90733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barcellos-Hoff MH. It takes a tissue to make a tumour: epigenetics, cancer and the microenvironment. J Mamm Gland Biol Neop. 2001;6(2):213–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1011317009329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolis G, Prigogine I. Exploring complexity. W.H. Freeman; N.Y: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon EC. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal. 1948;27:379–423. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miklos Rubin H. The role of the Genome Project in determining the gene function: insights from model organisms. Cell. 1996;86:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stent G. Strength and weakness of the genetic approach to the development of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1981;4:163–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricard J. Binding energy and the information content of some elementary biological processes. CR Acad Sci Paris, Sciences de la vie / Life Sciences. 2001;324 :297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)01291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shearin AL, Ostrander EA. Canine Morphology: Hunting for Genes and Tracking Mutations. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Vijver G, Van Speybroeck L, Vandevyvere W. Reflecting on complexity of biological systems: Kant and beyond? Acta Biotheor. 2003;51(2):101–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1024591510688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricard J, Bernardi G. Emergent Collective Properties, Networks And Information Biology. Elsevier Science; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406:378–381. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adami C. What is complexity? BioEssays. 2002;24:1085–1094. doi: 10.1002/bies.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longo G, Bailly F. Biological organization and negative entropy. J Biol Systems. 2009;17:63–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaitin GI. Information-theoretic computational complexity. IEEE Trans Inform Theory. 1974;IT-20:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spillman WB, Robertson JL, Huckle WR, Govindan BS, Meissner KE. Complexity, fractals, disease time, and cancer. Phys Rev E. 2004;70:1–12. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.061911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y, Eichler GS, Feng Y, Ingber DE, Huang S. Towards a holistic, yet gene-centered analysis of gene expression profiles: a case study of human lung cancers. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:1–11. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/69141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prigogine I, Nicolis G. Self-Organization in Non-Equilibrium Systems. Wiley; N.Y: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kauffman SA. Origins of Order: self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang HH, Hemberg M, Barahona M, Ingber DE, Huang S. Transcriptome wide noise controls lineage choice in mammalian progenitor cells. Nature. 2008;453:544–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert R, Othmer HG. The topology of the regulatory interactions predicts the expression pattern of the segment polarity genes in Drosophila melanogaster. J Theor Biol. 2003;223:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F, Long T, Lu Y, Ouyang Q, Tang C. The yeast cell-cycle network is robustly designed. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4781–4786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang S. Gene expression profiling, genetic networks, and cellular states: an integrating concept for tumorigenesis and drug discovery. J Mol Med. 1999;77:469–480. doi: 10.1007/s001099900023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aldana-Gonzalez M, Coppersmith S, Kadanoff LP. Boolean dynamics with random couplings. In: Kaplan E, Marsden JE, Sreenivasan KR, editors. Perspectives and problems in non-linear science. Springer; N.Y: 2003. pp. 23–89. [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Haan J. How emergence arises. Ecol Compl. 2006;3:293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Miquel PA. On physicalism and downward causation in developmental and cancer biology. Acta Biotheor. 2008;56(4):257–74. doi: 10.1007/s10441-008-9052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denton M, Marshall C. Laws of form revisited. Nature. 2001;410:417. doi: 10.1038/35068645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Virchow RLK. Cellular Pathology. London, UK: John Churchill; 1978. pp. 204–7. 1859. Special ed. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosai J. The continuing role of morphology in the molecular age. Modern Path. 2001;14:258–260. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammond TG, Lewis FC, Goodwin TJ, Linnehan RM, Wolf DA, Hire KP, Campbell WC, Benes E, O’Reilly KC, Globus RK, Kaysen JH. Gene expression in space. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:359. doi: 10.1038/7331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein GS, Van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Pockwinse SH, McNeil S. Implications for interrelationships between nuclear architecture and control of gene expression under microgravity conditions. FASEB. 1999;13:S157–S166. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pourati J, Maniotis A, Speigel D, Schaffer JL, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, Ingber DE, Stamenovic D, Wang N. Is cytoskeletal tension a major determinant of cell deformability in adherent endothelial cells? Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1283–C1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Withesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandelbrott BB. The fractal geometry of the Nature. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rangayyan RM, Nguyen TM. Fractal analysis of contours of breast masses in mammograms. J Dig Imag. 2007;20(3):223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10278-006-0860-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rangayyan RM, El-Faramawy NM, Desautels JEL, Alim OA. Measures of acutance and shape for classification of breast tumours. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1997;16(6):799–810. doi: 10.1109/42.650876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Losa GA, Merlini D, Nonnenmacher TF, Weibel ER, editors. Fractals in Biology and Medicine. Birkhauser Verlag; Basel: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baish JW, Jain RK. Fractals and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3683–3688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cross SS. Fractals in pathology. J Pathol. 1997;182:1–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199705)182:1<1::AID-PATH808>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cross SS, McDonagh AJG, Stephenson TJ, et al. Fractal and integer-dimensional analysis of pigmented skin lesions. Am J Dermatol. 1995;17:374–378. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199508000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Claridge E, Hall PN, Keefe M, et al. Shape analysis for classification of malignant melanoma. J Biomed Eng. 1992;14:229–324. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(92)90057-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gazit Y, Berk DA, Leunig M, Baxter LT, Jain RK. Scale-invariant behavior and vascular network formation in normal and tumour tissue. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;75:2428–2431. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michaelson JS, Cheongsiatmoy JA, Dewey F, et al. Spread of human cancer cells occurs with probabilities indicative of a nongenetic mechanism. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1244–1249. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tracqui P. Biophysical model of tumor growth. Rep Prog Phys. 2009;72:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landini G, Rippin JW. How important is tumour shape? Quantification of the epithelial connective tissue interface in oral lesions using local connected fractal dimension analysis. J Pathol. 1996;179:210–217. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199606)179:2<210::AID-PATH560>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eid RA, Landini G. Quantification of the global and local complexity of the epithelial-connective tissue interface of normal, dysplastic, and neoplastic oral mucose using digital imaging. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:475–482. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waliszewski P, Konarski J. Fractal structure of space and time is necessary for the emergence of self-organization, connectivity and collectivity in cellular system. In: Losa GA, Merlini D, Nonnenmacher TF, Weibel ER, editors. Fractals in Biology and Medicine. Birkhauser Verlag; Basel: 2002. pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Folkman J, Moscona A. Role of cell shape in growth control. Nature. 1978;273:345–349. doi: 10.1038/273345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ingber DE. How cells (might) sense microgravity. FASEB. 1999;13:S3–S15. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Theories of carcinogenesis: an emerging perspective. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2008;18:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingber DE. Mechanical control of tissue growth: function follows form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(33):11571–11572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505939102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mandelbrot BB. Stochastic models for the Earth's relief, the shape and the fractal dimension of the coastlines, and the number-area rule for islands. Proc Nat Acad SciUSA. 1975;72:3825–3828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith TG, Lange GD, Marks WB. Fractal methods and results in cellular morphology–dimensions,lacunarity and multifractals. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;69:123–136. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cutting JE, Garvin JJ. Fractal curves and complexity. Percept Psicophys. 1987;42:365–370. doi: 10.3758/bf03203093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheck F. Mechanics. Springer Verlag; Heidelberg, Germany: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toussaint O, Schneider ED. The thermodynamics and evolution of complexity in biological systems. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1998;120:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(98)10002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maffini MV, Calabro JM, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. Stromal regulation of neoplastic development: age-dependent normalization of neoplastic mammary cells by mammary stroma. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(5):1405–10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61227-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKinnell RG. Nuclear transfer in Xenopus and Rana compared. In: Harris R, Allin P, Viza D, editors. Cell Differentiation. Munksgaard; Copenhagen: 1972. pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pierce GB. The cancer cell and its control by the embryo. Am J Pathol. 1983;113 :116–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Seftor REB, Kasemeier-Kulesa J, Kulesa PM. Postovit L-M Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:246–255. doi: 10.1038/nrc2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D'Anselmi F, Valerio M, Cucina A, Galli L, Proietti S, Dinicola S, Pasqualato A, Manetti C, Ricci G, Giuliani A, Bizzarri M. Metabolism and cell shape in cancer: A fractal analysis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010 May 10; doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.05.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bowie JE, Young IT. An analysis technique for biological shape. Acta Cytol. 1977;21:739–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cesar RM, Jr, Costa L, da F. The application and assessment of multiscale Bending Energy for Morphometric characterization of neural cells. Rev Sci Instrum. 1997;68:2177–2186. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castleman KR. Digital Image Processing. Prentice-Hall; Engelewood Cliffs, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Foty R, Forgacs G, Pfleger C, Steimberg M. Liquid properties of embryonic tissues: measurement of interfacial tensions. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:2298–2301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Foty R, Pfleger C, Forcas G, Steimberg M. Surface tensions of embryonic tissues predict their mutual envelopment behaviour. Development (Camb) 1996;122:1611–1620. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rohrschneider M, Scheuermann G, Hoehme S, Drasdo D. Shape Characterization of Extracted and Simulated Tumor Samples using Topological and Geometric Measures. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS; 2007. pp. 6271–6277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trosko JE, Chang C-C, Upham BL, Tai M-H. Ignored hallmarks of carcinogenesis: stem cells and cell-cell communication. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1028:192–201. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cristini V, Frieboes HB, Gatenby R, Caserta S, Ferrari M, Sinek J. Morphologic instability and Cancer invasion. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(19):6772–6779. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferriera SC, Martins ML, Villa MJ. Morphology transitions induced by chemotherapy in carcinomas in situ. Physical Rev E. 2003;67:1–9. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.051914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips BT, Kimble J. A new look at TCF and beta-catenin through the lens of a divergent C. elegans Wnt pathway. Dev Cell. 2009;17(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.da Silva EC, Silva AC, de Paivam AC, Nunes RA. Diagnosis of lung nodule using Moran’s index and Geary’s coefficient in computerized tomography images. Pattern Anal Appl. 2008;11:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prigogine I, Wiame JM. Biologie et Thermodynamique des phenomenes irreversibles. Experientia. 1946;2:451–453. doi: 10.1007/BF02153597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zotin AA, Zotin AI. Phenomenological theory of ontogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 1997;41:917–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. Emergentism as a default: cancer as a problem of tissue organization. J Biosci. 2005;30(1):103–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02705155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang S, Ingber DE. Shape-dependent control of cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis: switching between attractors in cell regulatory networks. Exp Cell Res. 2000;261:91–103. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lelièvre SA, Weaver VM, Nickerson JA, Larabell CA, Bhaumik A, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Tissue phenotype depends on reciprocal interactions between the extracellular matrix and the structural organization of the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14711–14716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas CH, Collier JH, Sfeir CS, Healy KE. Engineering gene expression and protein synthesis by modulation of nuclear shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1972–1977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032668799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M, Boettiger D, Hammer DA, Weaver VM. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang S, Ernberg I, Kauffman S. Cancer attractors: A systems view of tumours from a gene network dynamics and developmental perspective. Sem in Cell & Develop Biol. 2009;20(7):869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gilbert SF, Opitz JM, Raff RA. Resynthesizing evolutionary and developmental biology. Dev Biol. 1996;173:357–372. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]