Abstract

Burn is associated with profound inflammation and activation of the innate immune system in multiple organ beds, including the lung. Similarly, toll-like receptors (TLR) are associated with innate immune activation. Nonetheless, it is unclear what impact burn has on TLR-induced inflammatory responses in the lung.

Methods:

Male C57BL/6 mice were subjected to burn (3rd degree, 25% TBSA) or sham procedure and 1, 3 or 7 days thereafter, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected and cells were isolated and cultured in vitro with specific TLR agonists as follows: Zymosan (TLR-2), LPS (TLR-4) and CpG-ODN (TLR-9). Supernatants were collected 48 hr later and assayed for inflammatory cytokine levels (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, TNF-α, KC, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES) by Luminex.

Results:

BAL fluid from sham and burn mice did not contain detectable cytokine levels. BAL cells, irrespective of injury, were responsive to TLR-2 and TLR-4 activation. Seven days after burn, TLR-2 and TLR-4 mediated responses by BAL cells were enhanced as evidenced by increased production of IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1β and RANTES.

Conclusions:

Burn-induced changes in TLR-2 and TLR-4 reactivity may contribute to the development of post-burn complications, such as ALI and ARDS.

Keywords: cytokines, burn, lung

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, approximately 2 million patients seek treatment for burn every year, of which 20% require hospitalization and at least 7,000 die [1]. Respiratory complications after burn, including ARDS and infection, are one of the leading causes of mortality in burn patients [2-4], even in the absence of inhalation injury [5, 6].

Major burn is associated with a local and systemic activation of the innate immune system and subsequent inflammation [7, 8]. As a consequence, Acute Lung Injury (ALI) and Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) develop due to an uncontrolled hyper-inflammatory response which involves excessive activation of various inflammatory cells (neutrophils, macrophages, airway epithelial cells) and excessive cytokine release (IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1).

Important sensors of the innate immune system, are pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect phylogenetically conserved molecular patterns found in many microorganisms [9]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the most studied of the 4 classes of PRRs and are widely expressed in many cell types [10]. Tissue beds continuously exposed to the external environment, such as lungs, express higher levels of TLRs mRNA [11], which appear to regulate epithelial cell survival after acute lung injury [12]. TLR activation induces a complex signaling cascade of events, leading to the induction of inflammatory genes and thereafter production of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, activation of complement, recruitment of phagocytic cells, and mobilization of professional antigen-presenting cells [13]. Several studies have shown that TLRs can be activated either by microbial (e.g. LPS, peptidoglycan) or endogenously derived ligands (heat shock proteins, necrotic cells, hyaluronic acid) [14, 15], supporting the hypothesis that injury augments host inflammatory responses and that enhanced inflammatory reactivity may play a significant role in the development of Systemic Inflammatory Response syndrome (SIRS) and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) [16]. Although the activation of a given TLR leads to specific genes transcription and release of pro-inflammatory mediators, the response may differ in the context of bacterial or non-bacterial derived ligand [17]. There is evidence showing the role of endogenous ligands (hyaluronic acid, HMGB1) released by dying or necrotic cells have in TLR-4-mediated gene regulation and enhanced expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, MIP-1, MIP-2 [18, 19].

Studies using several animal models of thermal injury have demonstrated enhanced TLR-mediated reactivity in the spleen [20], microvasculature vessels [21], heart [22], small bowel [23] and circulating γδ T-cells [24], showing that systemic and compartmental immunoinflammatory responses after burn are associated with post-injury complications.

Although substantial progress has been made developing effective treatments for respiratory complications after burn [4, 25, 26], additional understanding is required of the relative contributions of the innate and adaptive immune system in controlling the respiratory immune response after burn. In the current study, a mouse thermal injury model was used to determine how injury alters responses by lung cells to well-defined TLR-2, TLR-4 and TLR-9 agonists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals:

C57BL/6 male mice (18 to 22 gm;; 8 to 10 wk, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used for all experiments (6-7 mice per group). The mice were allowed to acclimatize in the animal facility for at least 1 week prior to experimentation. Animals were randomly assigned into either a thermal injury group or a sham treatment group and for the 3 different time points of the experiment. The experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and handling of laboratory animals.

Burn procedure:

Mice received a scald burn as described previously [27]. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized by i.m. injection of ketamine/xylazine, and the dorsal surface was shaved. The anesthetized mouse was placed in a custom insulated mold exposing 12.5% of their total body surface area (TBSA) along the right dorsum. The mold was immersed in 70°C water for 10 sec to produce a 3rd degree burn. The burn procedure was repeated on the left dorsum yielding a total burn size of 25% TBSA. The mice were then resuscitated with 1 ml of Ringer’s lactate solution administered by intraperitoneal injection and returned to their cages. The cages were placed on a heating pad for 2 hr until the mice were fully awake, at which time they were returned to the animal facility. Sham treatment consisted of anesthesia, dorsal surface shaving and resuscitation with Ringer’s lactate solution only.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, cell collection and culture:

Mice were sacrificed on day 1, 3 or 7 after burn or sham treatment and the tracheas were exposed through midline incision and cannulated with a sterile 18-gauge BD Angiocath™ catheter (Becton Dickinson Infusion Therapy Systems Inc., Sandy, UT). The lungs were lavaged serially with 1-ml aliquots of sterile lavage solution (PBS, 3 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM isoproterenol) for a total of 3 ml. The serial lavage aliquots recovered from a single mouse were pooled (~2.5 ml) and 5 ml of complete RPMI medium (RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 2% penicillin-streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine) was added. BAL cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400 g for 10 min at 4°C). BAL fluid was collected and stored at −80°C for subsequent cytokine analysis. Cells were collected and plated in 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 105/ml. Subsequently, TLR-2 (Zymosan, 10 μg/ml), TLR-4 (LPS, 1 μg/ml) and TLR-9 (CpG-ODN, 5 μM) agonists were added and incubated in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere for 48 hr at 37°C. TLR agonist concentrations were determined to be optimal from previously published literature values [20, 28] and preliminary studies (data not shown). Cell culture supernatants were collected after 48 hr and stored at −80°C for subsequent cytokine analysis

Cytokine, and chemokine determinations:

BAL fluid and cell culture supernatants were analyzed for cytokine/chemokine levels ((IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, TNF-α, KC, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES) by Luminex according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis:

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Comparisons were analyzed using ANOVA. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell yields and cytokine levels

There were no animal deaths after burn or sham procedures. The numbers of cells obtained by BAL are shown in Table 1. Burn did not significantly alter BAL cell yields as compared with respective sham groups. Cell free BAL fluid was analyzed for cytokine/chemokines levels. Detectable levels were not found either in the sham or the burn group.

Table 1.

BAL cell yield ( × 105) at 1, 3 and 7 days after burn or sham procedure.

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 1.51 ± 0.46a | 1.58 ± 0.6 | 0.60 ± 0.08 |

| Burn | 1.44 ± 0.35 | 1.36 ± 0.24 | 0.58 ± 0.14 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SE for 7-8 mice/group

TLR-2 and TLR-4 induced responses at 7 days post-injury

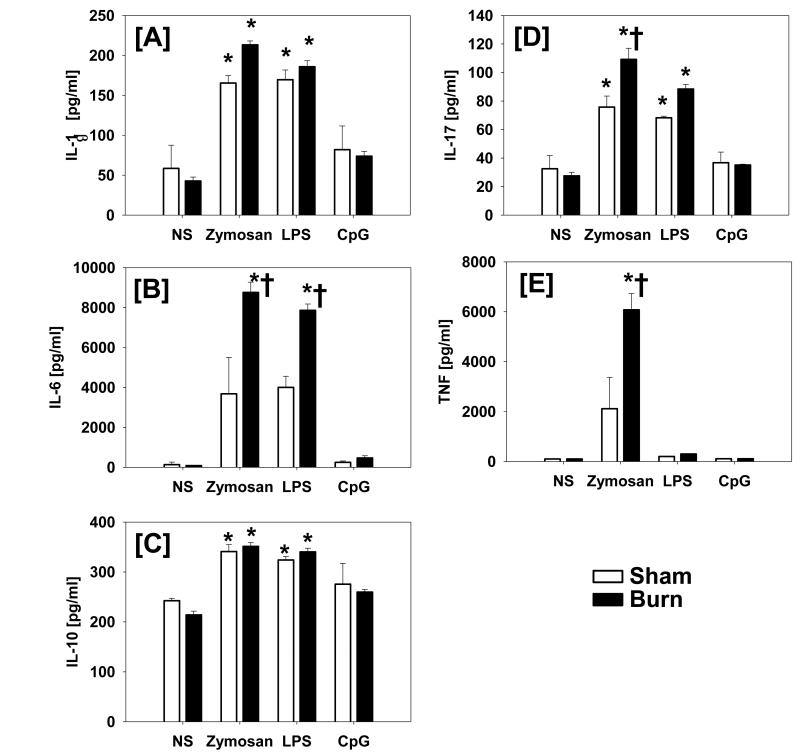

At 7 days after burn a significantly increased inflammatory response was observed in response to TLR-2 or TLR-4 induced activation as compared to BAL cells from sham animals. Zymosan (TLR-2 agonist) induced significantly increased production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α (Fig. 1) and a significantly increased production of the chemoattractants MCP-1 and MIP-1β (Fig. 2) as compared with responses from respective BAL cells from sham mice. LPS (TLR-4 agonist) also induced a significantly increased response in the burn group as compared to the sham in regard to IL-6, MIP-1β and RANTES (Fig. 1 and 2). CpG-ODN (TLR-9 agonist) induced activation did not differ from response by unstimulated cells in either group (data not shown).

Fig.1. Inflammatory cytokine production by BAL cells at 7 days after injury in response to TLR activation.

BAL cells were isolated at 7 days after injury or sham procedure and stimulated in vitro for 48 hrs with specific concentrations of the TLR-2 agonist zymosan, the TLR-4 agonist LPS and the TLR-9 agonist CpG-ODN as described in Materials and Methods. Constitutive cytokine production was determined in non-stimulated cultures (NS). Supernatants were collected and IL-1β [A], IL-6 [B], IL-10 [C], IL-17 [D] and TNF-α [E] levels were determined by Luminex. Data are mean ± SE for 6-7 mice/group. *, p<0.05 as compared with respective unstimulated group. †, p<0.05 as compared with respective sham group.

Fig.2. Chemokine production by BAL cells at 7 days after injury in response to TLR activation.

BAL cells were isolated at 7 days after injury or sham procedure and stimulated in vitro for 48 hrs with specific concentrations of the TLR-2 agonist zymosan, the TLR-4 agonist LPS and the TLR-9 agonist CpG-ODN as described in Materials and Methods. Constitutive chemokine production was determined in non-stimulated cultures (NS). Supernatants were collected and KC [A], MCP-1 [B], MIP-1α [C], MIP-1β [D] and RANTES [E] levels were determined by Luminex. Data are mean ± SE for 6-7 mice/group. *, p<0.05 as compared with respective unstimulated group. †, p<0.05 as compared with respective sham group.

Production of IL-1β was significantly increased after either TLR-2 or TLR-4 activation and was similar for both the sham and the burn group (Fig. 1A). A similar response was observed for IL-10 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, we observed a significantly increased IL-6 response after TLR-2 and TLR-4 activation in the burn group only (Fig. 1B). IL-17 production was increased after TLR-2 or TLR-4 activation in both groups; however, the TLR-2 mediated response was significantly increased in the burn group as compared with the sham (Fig. 1D). TLR-2 induced TNF-α production was greater in the burn group, as compared to the sham group (p<0.05). In contrast, TLR-4 activation did not induce a TNF-α response in either group (Fig. 1E). BAL cells produced elevated levels of KC and MIP-1α in response to TLR-2 and TLR-4 stimulation; however, responses were similar in the sham and burn groups (Fig. 2A, 2C). The TLR-induced production of MCP-1, MIP-1β and RANTES was significantly greater in the burn group; however, their particular response was dependent on the TLR ligand employed. Burn induced a significant MCP-1 response after TLR-2 activation only (Fig. 2B). In contrast, burn significantly increased the TLR-4 mediated production of RANTES (Fig. 2E). The MIP-1β response was significantly increased after burn in both the TLR-2 and TLR-4 activated cells (Fig. 2D).

TLR-induced responses at 1 and 3 days post-injury

At 1 and 3 days after burn or sham procedure, the TLR-2 ligand zymosan induced significant (p<0.05) production of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, TNF-α, KC, MCP-1 and MIP-1α by BAL cells. Sham responses were similar to that observed at day 7. The responses were not different for BAL cells from sham and burn mice (data not shown).

At 1 and 3 days after burn or sham procedure, TLR-4 mediated activation induced by LPS resulted in significant production of IL-1, IL-10, IL-17, KC, MIP-1α and RANTES. The responses were similar for BAL cells from both sham and burn mice (data not shown).

The TLR-9 ligand, CpG-ODN did not induce a significant response in either cell population or at any times evaluated (data not shown). Sham responses were similar to that observed at day 7.

DISCUSSION

Major burn induces the systemic production of proinflammatory mediators which are associated with the development of SIRS and an elevated risk of end organ failure, particularly ALI and ARDS. In the present study, burn significantly increased the TLR-2 and TLR-4 mediated inflammation as evidenced by BAL cells enhanced production of IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1β and RANTES, 7 days after injury. TLR-9 does not appear to be involved in the lung inflammatory response after burn. Similarly, Susuki et al, showed that TLR-9 mRNA was almost absent in alveolar macrophages and showed no sensitivity to CpG-ODN stimulation [29]. In contrast to our results, Zhang et al [30], recently showed a marked inflammatory response in the lungs mediated by TLR-9 activation of lung neutrophils in a trauma injury model, however, the cells isolated in our study were primarily of a myeloid lineage.

The initial response after burn triggers a non-specific innate immune system, promptly activated after recognition of the diverse repertoire of injury derived danger molecules or microbial pathogens. The innate immune system provides initial protection from pathogens while appropriately licensing and shaping the adaptive immune response [10]. The field of innate immunity research has undergone a veritable rebirth since the discovery of mammalian TLRs, a family of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) nonclonal germline-encoded, implicated in regulation of the immune response in several diseases as atherosclerosis, allergies, autoimmunity, burn and sepsis [31]. Because TLRs recognize conserved molecules shared among members of a particular class of microbes (e.g., LPS from Gram-negative pathogens and ssRNA from RNA viruses), the entire pathogenic universe can be readily sampled by a small group of receptors [32]. Interaction of TLRs with their specific ligands triggers the cascade of signaling pathways and ultimately the activation of transcription factors such as NFκB, MAP kinases and Interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), inducing the transcription of inflammatory cytokines, controlling antigen uptake, antigen presentation, dendritic cells maturation [33] and cell proliferation and survival [34]. Inflammatory mediators play a key role in the pathogenesis of ALI and ARDS after burn. IL-6 is produced by a wide range of cells including macrophages, endothelial cells and fibroblasts in a variety of acute conditions such as burns. IL-6 stimulates the synthesis of acute phase proteins and circulating levels are excellent predictors of the severity of ARDS [35]. TNF-α, one of the major mediators of shock, derived predominantly from activated macrophages, induces additional cytokines, reactive oxygen species and up-regulates cell adhesion molecules [36]. The chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1β and RANTES are predominantly chemoattractants for monocytes and lymphocytes and play a critical role in ARDS of various etiologies [37].

Studies by Finnerty et al. and our laboratory [38,51] have shown that the systemic inflammatory response elicited after burn follows a similar pattern to what we have found in the BAL response In particular Finnerty et al. observed a late (after 24 hr) increase in plasma levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-17. Previous findings from our laboratory have shown significant plasma levels of IL-6, IL-10, KC and MCP-1 up to 3 days post-injury, which return to normal levels by 7 days post-injury. Variations in the systemic inflammatory response between our findings and those of Finnerty et al. may be in part related to the severity of injury between the two models, as Finnerty e al. used a much more severe injury then us (i.e., 40% TBSA vs. 25% TBSA).

The burn-elicited inflammatory response can be specific to a particular tissue bed [39]. The clinical significance of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome after thermal injury is well described [40]. Studies by Ipaktchi et al, have shown that the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), plays a fundamental role in the development of the systemic inflammatory response after burn [41]. The inhibition of this pathway attenuated acute lung injury and improved survival. Additionally, Ipaktchi et al showed that the burn injury itself constituted the source of ongoing innate immune stimulation, where TLR play a fundamental role [42].

In the present study, we believe that macrophages are the innate immune cells involved in the observed inflammatory response, since qualitative visual analysis of the BAL cells was consistent with a macrophage phenotype. As a first line of the pulmonary defense against invading pathogens, alveolar macrophages, mobile and capable of phagocytosis, are crucial for adequate innate immune responses [43-45]. Studies of Schwacha et al, have shown the critical role of macrophages as major producers of IL-6, TNF-α, reactive oxygen intermediates [7] and also bearing an increased productive capacity of these mediators after burn [46]. Macrophages have been shown to mediate remote lung injury by IL-6 production in a trauma/hemorrhage model [47]. Additionally, macrophages widely express TLRs on their surface and upon activation, the TLR-mediated response is a major mechanism of cytokine production 7 days after burn [20]. These findings are consistent with previous observations of Schwacha et al, [39] suggesting that at 7 days after injury the hyperactive macrophage phenotype is important supporting the pro-inflammatory response after burn. However, other cells, like CD4+CD25+ T cell subset, have also been shown to be potentially involved in controlling the inflammatory response for which the innate immune system is primed after serious injury as demonstrated by studies of Murphy et al [48].

Our study shows that the TLR-2 and TLR-4 mediated inflammatory responses by the pulmonary alveolar macrophages after burn is a late response as evidenced by the significantly increased production of IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α and chemokines 7 days after burn. Cairns et al, previously demonstrated that splenocytes induced by TLR-2 and TLR-4 ligands 14 days after burn, resulted in increased inflammatory cytokine production and a decreased sensitivity to cell death after those TLR ligations [20]. In contrast, Schwacha et al, have shown a marked increase in the number of circulating γδ T-cells expressing TLR-2, 24 hr after burn [24]. Burn-induced changes in TLR-2 and TLR-4 reactivity may contribute to the development of post-burn complications such as ALI and ARDS. Our results show that burn patients might have an increased susceptibility to respiratory complications in a sub-acute phase following thermal injury. Because pulmonary complications have been found to cause or directly contribute to mortality in up to 77% of burn patients, early detection and treatment may significantly alter treatment outcomes [49].

In the current study, we focused on the pulmonary response after burn, since respiratory complications, especially pneumonia, are the leading causes of mortality in this patient population. In a non-infectious lung injury model, mice deficient in both TLR-2 and TLR-4 showed impaired leukocyte recruitment, increased tissue injury and decreased survival [12]. Iwasaki and Medzhithov recently discussed how exogenous TLR agonists activate genes involved in inflammation, tissue repair and adaptive immune response, while an endogenous TLR ligand only activates genes involved in inflammation and tissue repair [9]. Jiang et al, have demonstrated the importance of TLR-4 integrity in the epithelial cell function after lung injury [12]. Whether the modulation of this inflammatory response is mediated by changes in the activity of certain kinases pathways after TLR ligation or is related to TLR receptors expression requires further investigation. Recent studies by Chen et al, showed that increased expression of TLR-4 and subsequent signaling mediators in peritoneal cells of burn mice after hypertonic fluid resuscitation is associated with enhanced host defense against bacterial challenge [50].

In conclusion, our findings show that at 7 days post-burn, but not earlier, TLR responses are enhanced in lung cells. This TLR hyper-responsiveness likely contributes to pulmonary complications after burn. An improved understanding of how injury modulates innate immune responses will reveal new insights into ways in which normal immune function could be restored after critical injury.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support was provided by National Institutes of Health grant GM079122. These finding were presented in part at the 42nd annual meeting of the American Burn Association in Boston, MA. Authors’ contributions: RFO was responsible for the data analysis, scientific interpretation and drafted the first draft of the manuscript. MR was responsible for experimental design, ELISA analysis, data analysis and scientific interpretation. QZ was responsible for the animal experiments and ELISAs. MGS was responsible for scientific conception, design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sio SW, et al. Early protection from burn-induced acute lung injury by deletion of preprotachykinin-A gene. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(1):36–46. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1073OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez R, et al. Causes of mortality by autopsy findings of combat casualties and civilian patients admitted to a burn unit. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(3):348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams FN, et al. The leading causes of death after burn injury in a single pediatric burn center. Crit Care. 2009;13(6):R183. doi: 10.1186/cc8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons PE, et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000149854.61192.dc. discussion 230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dancey DR, et al. ARDS in patients with thermal injury. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(11):1231–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00003763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liffner G, et al. Inhalation injury assessed by score does not contribute to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in burn victims. Burns. 2005;31(3):263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwacha MG. Macrophages and post-burn immune dysfunction. Burns. 2003;29(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeschke MG, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327(5963):291–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manicassamy S, Pulendran B. Modulation of adaptive immunity with Toll-like receptors. Semin Immunol. 2009;21(4):185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarember KA, Godowski PJ. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168(2):554–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang D, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1173–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West AP, Koblansky AA, Ghosh S. Recognition and signaling by toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:409–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.115827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy TJ, et al. Injury, sepsis, and the regulation of Toll-like receptor responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(3):400–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirali AC, Goldstein DR. Activation of the innate immune system by the endogenous ligand hyaluronan. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2008;13(1):20–5. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3282f3df04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson HM, et al. Injury primes the innate immune system for enhanced Toll-like receptor reactivity. J Immunol. 2003;171(3):1473–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorne E, Dupont H, Abraham E. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4: initiators of non-septic inflammation in critical care medicine? Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(11):1826–35. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1983-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor KR, et al. Recognition of hyaluronan released in sterile injury involves a unique receptor complex dependent on Toll-like receptor 4, CD44, and MD-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(25):18265–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sha Y, et al. HMGB1 develops enhanced proinflammatory activity by binding to cytokines. J Immunol. 2008;180(4):2531–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cairns BA, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 ligation results in complex altered cytokine profiles early and late after burn injury. J Trauma. 2008;64(4):1069–77. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318166b7d9. discussion 1077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslin JW, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to microvascular inflammation and barrier dysfunction in thermal injury. Shock. 2008;29(3):349–55. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181454975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruns B, et al. Alterations in the cardiac inflammatory response to burn trauma in mice lacking a functional Toll-like receptor 4 gene. Shock. 2008;30(6):740–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318173f329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber NL, et al. Remote thermal injury increases LPS-induced intestinal IL-6 production. J Surg Res. 2010;160(2):190–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwacha MG, Daniel T. Up-regulation of cell surface Toll-like receptors on circulating gammadelta T-cells following burn injury. Cytokine. 2008;44(3):328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancio LC. Airway management and smoke inhalation injury in the burn patient. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(4):555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander M, Chaudry IH, Schwacha MG. Relationships between burn size, immunosuppression, and macrophage hyperactivity in a murine model of thermal injury. Cell Immunol. 2002;220(1):63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102(7):2660–2669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki K, et al. Impaired toll-like receptor 9 expression in alveolar macrophages with no sensitivity to CpG DNA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(7):707–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1078OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464(7285):104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(10):975–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388(6640):394–7. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388(4):621–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Jiang S, Tapping RI. Toll-like receptor signaling in cell proliferation and survival. Cytokine. 2010;49(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frink M, et al. IL-6 predicts organ dysfunction and mortality in patients with multiple injuries. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:49. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhatia M, Moochhala S. Role of inflammatory mediators in the pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Pathol. 2004;202(2):145–56. doi: 10.1002/path.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finnerty CC, et al. Cytokine expression profile over time in burned mice. Cytokine. 2009;45(1):20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwacha MG, Schneider CP, Chaudry IH. Differential expression and tissue compartmentalization of the inflammatory response following thermal injury. Cytokine. 2002;17(5):266–74. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pruitt BA, Jr., Erickson DR, Morris A. Progressive pulmonary insufficiency and other pulmonary complications of thermal injury. J Trauma. 1975;15(5):369–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ipaktchi K, et al. Attenuating burn wound inflammation improves pulmonary function and survival in a burn-pneumonia model. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2139–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000280568.61217.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ipaktchi K, et al. Attenuating burn wound inflammatory signaling reduces systemic inflammation and acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):8065–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor PR, et al. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:901–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon SB, Read RC. Macrophage defences against respiratory tract infections. Br Med Bull. 2002;61:45–61. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marriott HM, Dockrell DH. The role of the macrophage in lung disease mediated by bacteria. Exp Lung Res. 2007;33(10):493–505. doi: 10.1080/01902140701756562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwacha MG, et al. Impact of thermal injury on wound infiltration and the dermal inflammatory response. J Surg Res. 2010;158(1):112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mommsen P, et al. Productive capacity of alveolar macrophages and pulmonary organ damage after femoral fracture and hemorrhage in IL-6 knockout mice. Cytokine. 2011;53(1):60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy TJ, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control innate immune reactivity after injury. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2957–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosier MJ, et al. Microbial contamination in burn patients undergoing urgent intubation as part of their early airway management. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(2):304–10. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318166daa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen LW, et al. Hypertonic saline enhances host defense and reduces apoptosis in burn mice by increasing toll-like receptors. Shock. 2011;35(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e86f10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwacha MG, Nickel E, Daniel T. Burn injury-induced alterations in wound inflammation and healing are associated with suppressed hypoxia inducible factor-expression. Mol Med. 2008;14:628–633. doi: 10.2119/2008-00069.Schwacha. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]