Abstract

Background

The anterosuperior approach used for reverse shoulder arthroplasty is an intermediate between the transacromial approach originally proposed by Paul Grammont and the anterosuperior approach described by D. B. Mackenzie for shoulder arthroplasty. As an alternative to the deltopectoral approach, the anterosuperior approach has the advantages of simplicity and postoperative stability.

Description of Technique

The anterior deltoid is divided from the anterior edge of the acromioclavicular arch, allowing exposure to the glenoid for glenosphere implantation.

Patients and Methods

We used the findings of published studies to assess instability, function and pain scores, scapular notching, and complications after this approach.

Results

In a comparison of the deltopectoral and anterosuperior approaches in 527 reverse arthroplasties with a minimum 2-year followup, postoperative instability rate was greater with the deltopectoral (5.1%) than with the anterosuperior (0.8%) approach. Other published studies confirm this finding. No differences in Constant-Murley score or active mobility were found. Scapular notching occurred at similar rates after the anterosuperior (74%) and deltopectoral (63%) approaches. Humeral diaphyseal fracture rates were similar, whereas the acromial fracture rate was higher using the deltopectoral approach. Loosening tended to occur more often with the anterosuperior approach.

Conclusions

The anterosuperior approach can be used in primary and revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty, as well as in acute humeral head fracture. Its main apparent advantages are simplicity, ease of axial humerus preparation, quality of frontal exposure of the glenoid, and due to subscapularis tendon preservation, a low risk of postoperative instability. Its drawbacks are risk of inaccurate glenoid positioning, axillary nerve palsy, and deltoid weakening.

Introduction

The indication for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is most commonly rotator cuff disease in association with glenohumeral arthritis. Some surgeons recommend a superior approach when open surgery is used for rotator cuff repair, while others prefer an anterior deltopectoral approach, which saves the deltoid. The same alternatives can be used for implanting shoulder prostheses. While many surgeons favor the deltopectoral approach, the “anterosuperior exposure,” as described by Mackenzie [13] in 1993, provides better visualization of the glenoid surface during its preparation and enhances the reaming precision and accuracy of component fixation. Therefore, some surgeons prefer the anterosuperior approach when implanting a reverse prosthesis, owing to its advantages regarding exposure of the glenoid [19]. Nonetheless, some surgeons continue to use the deltopectoral approach, which avoids the dividing of the deltoid muscle and circumvents other possible deltoid complications.

Our aims are to (1) describe the anterosuperior approach and its application to RSA and (2) assess instability, function, pain scores, scapular notching, and complications after this approach using the findings of published studies in the literature.

Surgical Technique

Inspired by Neviaser [16], Mackenzie [13, 14] recommended an original approach to prosthetic shoulder surgery in 1993. The patient lies in the beach chair position with a 60° tilt of the chest, at the lateral extremity of the table, leaving the anterior and posterior sides of the shoulder free from obstruction; support under the medial edge of the scapula facilitates exposure. The front arm rests on an armrest and is draped free. The skin incision extends from the posterior part of the acromioclavicular joint. It is 9 cm long and runs along the axis of the arm. The surgeon dissociates the anterior deltoid fibers and positions a stop suture on the distal portion of the dissociation to prevent any injury of the axillary nerve. The surgeon then resects the distal 1 cm of the clavicle and excises the coracoacromial ligament, allowing an acromioplasty that facilitates exposure. At the end of surgery, the wound is drained and the deltoid is closed using laterolateral sutures.

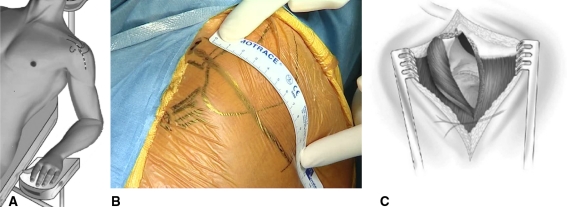

The anterosuperior approach used for RSA is a surgical approach different from the transacromial approach originally described by Grammont and Baulot [10] and the anterosuperior approach described by Mackenzie [13]. The positioning of the patient is similar, but the elbow must be free of any support to enable the operating assistant to apply a proximally directed force at the elbow to allow proximal subluxation of the humeral head (Fig. 1A). The surgeon stands laterally to the shoulder at the axis of the scapula. Two assistants are useful, with one positioned on each side of the patient. The skin incision begins on the anterior part of the acromioclavicular joint, 1 cm medially. It is directed toward the front edge of the clavicle, stretching 5 mm behind the anterior acromion and 3 cm beyond the lateral side of the acromion. It continues in the direction of the deltoid’s fibers (Fig. 1B), remaining distant from the axillary nerve that horizontally crosses the acromion at 5 cm. The surgeon divides the deltoid muscle fibers to open and excise the subacromial bursa. The surgeon then divides the anterior deltoid from the anterior edge of the acromion and takes away the proximal attachment of the coracoacromial ligament as one piece (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1A–C.

(A) A computer-generated image shows the setup for an anterosuperior approach to RSA. (B) An intraoperative photograph indicates the bony landmarks. (C) A drawing illustrates the deltoid division. RSA = reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

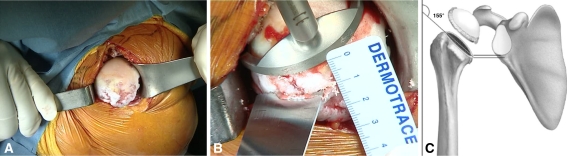

Acromioplasty must be avoided so that it does not weaken the acromion. The surgeon may resect the anterior spur to facilitate exposure and healing of the deltoid reinsertion. After further excision of the bursa, the surgeon explores the cuff. The subscapularis tendon is usually clear; if the tendon of the long portion of the biceps is still present, its intra-articular portion should be resected. Exploration of the residual posterior cuff is possible by holding the upper limb in extension and light internal rotation. In the absence or tear of the teres minor tendon, the surgeon can perform a latissimus dorsi transfer. Proximally directed force on the elbow while the arm is in extension allows the surgeon to subluxate the humeral head superiorly and proceed to the humeral step of the prosthesis (Fig. 2A). The surgeon then places the centromedullary humeral cutting guide at the top of the humeral head and usually sets it with 20° retroversion. The guide allows cutting the head with an oscillating saw at the appropriate level. The humeral head osteotomy should be generous to allow optimal exposure of the glenoid (Fig. 2B). With the deltopectoral approach, the humeral osteotomy should be minimal to allow correct tension and minimize the risks of instability. The approach allows a wide humeral osteotomy that will free the glenoid exposure from any obstacle. The surgeon should incline the osteotomy at 155°, meeting the inside lower edge of the glenoid and enabling the humeral retractor to be placed (Fig. 2C). After preparing the humerus, a trial humeral prosthesis is inserted to protect the humeral epiphysis during the time of glenoid preparation.

Fig. 2A–C.

(A) An intraoperative photograph shows an exposed humeral head during anterosuperior subluxation. (B) Placement of the jig is demonstrated. (C) A drawing indicates the cutting direction.

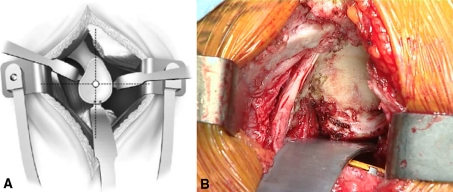

The surgeon then completes glenoid exposure, labrum resection, and peripheral capsular release. The inferior labrum is carefully released with a knife while maintaining contact with the bony rim and avoiding electric cautery, considering the proximity of the axillary nerve, which is not visualized. This allows the positioning of a hooked retractor that presses the humeral epiphysis, which is protected by its trial prosthesis (Fig. 3). It may be necessary for the surgeon to place the upper limb in flexion to facilitate the work of the glenoid, perpendicular to the surface.

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) A drawing illustrates the glenoid exposure and retractors placement. (B) An intraoperative photograph shows the actual procedure.

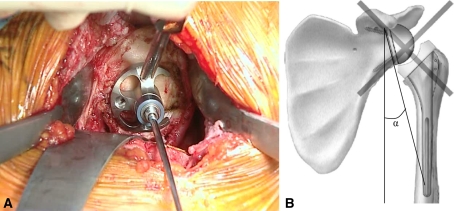

Preparation of the glenoid begins with an assessment of wear and loss of bone stock. Any major wear of the glenoid, often superior, may require the addition of a structural graft to be taken from the humeral head. The glenoid exposure should allow the free choice of the entry point of the drill guide and the direction of the central peg for the implantation of the base plate. It is important to avoid upward pressure exerted by the proximal humerus leading to implantation of the glenoid with a superior tilt (a factor in loosening) or to positioning the center hole too high with a risk of inferior bone overlap (which can generate scapular notches) (Fig. 4). The goal of a full glenoid release and an adequate humeral osteotomy is to allow proper positioning of the central hole and inclination of the instruments, position the glenoid with a slight inferior tilt, and overlap with the sphere the inferior glenoid to optimize the biomechanics of the implant and limit the impact of the scapular notches. According to advocates of the deltopectoral approach, the risk of inaccurate positioning of the glenoid is the main risk in the anterosuperior approach [12, 15]. Inaccurate positioning may explain the higher rate of glenoid loosening with this approach [12, 15].

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) Glenoid reaming is demonstrated. The instrument’s direction must be correct to avoid superior tilt. (B) A drawing illustrates superior tilt.

Once the glenoid implant is in place, the surgeon subluxates the humerus superiorly and anteriorly and cuffs the trial humeral stem with a trial insert; the reduction enables the surgeon to test the stability and tension. The presence of the subscapularis tendon is an effective anterior barrier. The surgeon determines the thickness of the insert by the stability in adduction and by assessing the tension of both the conjoined tendon and the lateral deltoid. The thinnest insert (6 mm) is most often used. Then, the final humeral stem is implanted, with or without cement, reproducing the retroversion angle given to the trial prosthesis. It is cuffed by the definitive insert in polyethylene, the lateral subluxation is reduced, and the surgeon checks stability and mobility.

Given the risk of hematoma in the subacromial dead space, we perform closure over drains. We use four nonabsorbable mattress sutures to reinsert the anterior deltoid. Suture points are selected to transpose the anterior deltoid and the proximal part of the coracoacromial ligament forward simultaneously. We first place the medial suture in the acromioclavicular joint, taking advantage of the strength of its ligament system. The middle two sutures are placed in the acromion transosseously and transperiosteally. The final suture is lateroacromial in the proximal part of the deltoid aponeurosis, which has good tissue strength (Fig. 5).

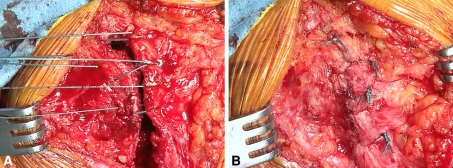

Fig. 5A–B.

(A) An intraoperative photograph shows the sutures during deltoid reattachment. Four nonabsorbable mattress sutures are used for the reinsertion of the anterior deltoid. (B) The sutures are shown in place.

In the case of fragmentation of the acromion, as is sometimes seen with acetabulization of the acromial arch (Fig. 6), the bone rim is often extended forward. We prefer a transacromial approach, in the prolongation of the anterior edge of the clavicle, to the division of the anterior deltoid, which may be aggressive with the fragile anterior acromion, risking necrosis and weakening of the deltoid. At the end of surgery, we pass sutures through fragments of acromion and the bony rims using transosseous sutures. We have identified no cases of secondary migration.

Fig. 6A–B.

(A) AP and (B) lateral radiographs show fragmentation of the acromion.

In the case of revision surgery, which often requires the extraction of a humeral stem in place, surgeons can also use the anterosuperior approach. The risk of postoperative instability can be limited by preserving the subscapularis tendon and anterior fascia. The intramedullary preparation of the humerus made possible by this superior approach facilitates epiphysis cement removal and the installation of a humeral stem extractor. If the stem extraction is difficult, the surgeon may perform osteotomy of the humerus on the lateral side, taking particular care with the axillary nerve. The surgeon can then address humeral fragmentation by using a long humeral cemented stem and proximal osteosutures (Fig. 7). Sometimes, this extraction is impossible to do without an anterior approach of the humeral diaphysis. In these cases, it is possible to combine the anterosuperior approach with a “low deltopectoral approach,” enabling osteotomy and fixation of the humerus along with the subscapularis tendon and the anterior stabilizers of its proximal part.

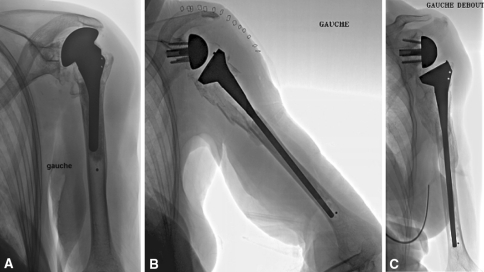

Fig. 7A–C.

(A) A preoperative radiograph shows a RSA that used the anterosuperior approach. (B) A radiograph shows the same shoulder immediately postoperatively. (C) A radiograph shows the same shoulder at 1-year followup. RSA = reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Postoperatively, in most cases, the upper limb is immobilized with a simple sling, enabling early recovery (Day 1). The soft tissue tension can lead to the patients using an abduction splint for the first few weeks.

Search Strategy and Criteria

To compare the anterosuperior approach to the deltopectoral approach, we analyzed two symposia dedicated to RSA, “The Nice Shoulder Course 2006” [12, 17] reporting on 457 RSAs and “The French Multicentric Study” [15] reporting on 527 RSAs.

We searched PubMed, using “reverse shoulder arthroplasty” or “reverse shoulder prosthesis” as search terms, including articles published up to 2010. Using these search terms, we identified a total of 181 articles. We excluded biomechanical studies and allowed articles analyzing surgical approach. We identified seven single-center studies reporting on primary RSA [2, 8, 12, 17, 18, 20, 21]. Seven additional studies described revision RSA [2, 5–7, 11, 17, 20].

Results

The risk of instability appears to be higher for the deltopectoral approach than for the anterosuperior approach in primary RSA (Table 1) and revision RSA (Table 2).

Table 1.

Risks of instability and scapular notch in primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty according to surgical approach

| Study | Approach | Number of patients | Followup (months) | Instability | Notch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boileau et al. [2] | DP | 21 | 40 | 4.8% | |

| Simovitch et al. [18] | DP | 77 | 44 | 44% | |

| Werner et al. [20] | DP | 37 | 38 | 5.4% | |

| Frankle et al. [8] | DP | 60 | 33 | 1.7% | 0% |

| Nové-Josserand [17] | DP | 92 | 49 | 9% | |

| Lévigne [12] | DP | 92 | 49 | 46% | |

| Nové-Josserand [17] | AS | 37 | 49 | 0% | |

| Lévigne [12] | AS | 37 | 49 | 66% | |

| Young et al. [21] | AS | 45 | 38 | 0% | 24% |

DP = deltopectoral; AS = anterosuperior.

Table 2.

Risks of instability and scapular notch in revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty according to surgical approach

| Study | Approach | Number of patients | Followup (months) | Instability | Notch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boileau et al. [2] | DP | 19 | 40 | 10.5% | |

| Werner et al. [20] | DP | 21 | 38 | 14.3% | |

| Cuff et al. [6] | DP | 17 | 43 | 5.9% | |

| Holcomb et al. [11] | DP | 14 | 33 | 7.1% | |

| Chacon et al. [5] | DP | 25 | 30 | 8% | |

| Nové-Josserand [17] | DP | 84 | 44 | 10.7% | |

| Nové-Josserand [17] | AS | 5 | 44 | 0% | |

| Delloye et al. [7] | AS | 4 | 81 | 0% | 100% |

DP = deltopectoral; AS = anterosuperior.

The two approaches were compared in a multicenter study of the French Society of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, which reported on 527 primary RSAs for massive cuff tears or cuff tear arthropathies with a followup of more than 2 years in 11 European specialist centers [15] (Table 3). Among these 527 RSAs, 300 were implanted using a deltopectoral approach and 227 using an anterosuperior approach. The interpretation of these results must take into account the longer followup for the anterosuperior approach. The rate of postoperative instability was greater (p < 0.001) with the deltopectoral approach than with the anterosuperior approach: 5.1% versus 0.8%, respectively. We found no differences in the Constant-Murley score or active mobility between the two approaches. On radiographs, scapular notching occurred in a similar number of patients after the anterosuperior approach compared to the deltopectoral approach: 74% versus 63%, respectively; the slight difference might be explained by the longer followup in the former group. Postoperative axillary paresis was infrequent (1.1%) and we identified no tears in the deltoid attachments. Humeral diaphyseal fractures occurred in 0.5% of cases, with similar rates between the two approaches. Fractures of the spine of the scapula and the acromion represented 4.1% of cases, with a higher (p = 0.02) frequency when using the deltopectoral approach. Loosening of the glenoid occurred in 3.4% of cases, with an average followup of 52 months. Loosening tended to occur more frequently in cases using an anterosuperior approach than in those using a deltopectoral approach: 11 of 227 (4.8%) versus seven of 300 (2.3%), respectively. Loosening was often associated with superior tilt in the glenoid implant positioning.

Table 3.

Results of the multicentric study [15]

| Variable | Overall results | Deltopectoral approach | Anterosuperior approach | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 527 | 300 | 227 | |

| Followup (months) | 52 | 43 | 59 | 0.11 |

| Constant-Murley score (points) | 62.4 | 62.5 | 62.2 | 0.39 |

| Pain score (points) | 12.6 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 0.01 |

| Anterior active elevation | 130° | 127° | 132° | 0.24 |

| Instability | 3.3% | 5.1% | 0.8% | < 0.001 |

| Glenoid loosening | 4.1% | 2.3% | 6.6% | 0.04 |

| Scapular notch | 68% | 63% | 74% | 0.03 |

| Humeral fracture | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.21 |

| Acromial fracture | 4.1% | 5.6% | 2.2% | 0.02 |

| Axillary nerve palsy | 1.1% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 0.13 |

Discussion

The questions concerning a surgical approach are its utility, advantages, and disadvantages. The vast majority of RSAs are performed using either the anterosuperior or deltopectoral approach [15]. RSA is associated with relief of pain and restoration of function but has a high risk of complications, which we believe can be attributed to the surgical approach. The choice between the anterosuperior and deltopectoral approach depends primarily on the experience of the surgeon. Secondarily, it is guided by the indication and analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of both techniques. Our aims were to (1) describe the anterosuperior approach and its application to RSA and (2) assess instability, function and pain scores, scapular notching, and complications after this approach using the findings of published studies in the literature.

We acknowledge limitations of our study. First, we report data from the literature, with studies that did not analyze the same variables; nevertheless, the major clinical data (stability) were always analyzed. Second, in the French multicentric study, the data are complete, but the followup is short for analyzing glenoid loosening. The data must be evaluated with a longer followup.

The main advantages of the deltopectoral approach are the preservation of the deltoid muscle, exposure of the lower pole of the glenoid to facilitate glenoid implant positioning, possibility of inferior extension to control the proximal humerus, and ability to perform a latissimus dorsi transfer as described by Boileau et al. [1]. Its main drawbacks are the interruption of the continuity of the subscapularis tendon (the main anterior stabilizer), need for an extended capsular release (which is a factor for instability), and lack of control in posterior cuff and glenoid screwing. The main advantages of the anterosuperior approach are simplicity, ease of axial preparation of the humerus, quality of the frontal exposure of the glenoid, and preservation of the subscapularis tendon. Its drawbacks are the risk of weakening of the anterior deltoid (mechanical or neurologic by damage to the distal branches of axillary nerve) and inaccurate positioning (excess height and superior tilt) of the glenoid component.

Many authors consider RSA for treatment of complex fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly; the anterosuperior approach has a particular interest in this specific indication [3, 4, 9]. In addition to the quality of exposure from the proximal humerus to the glenoid, it offers the advantages of better conditions of release and fixation of the greater tuberosity when compared to the deltopectoral approach.

The anterosuperior and deltopectoral approaches both allow reliable implantation of reverse shoulder prostheses. For us, the anterosuperior approach has the advantage of simplicity, a quality exposure of the humerus and glenoid, and the near-absence of risks of postoperative instability. Users should be aware of the positioning of the glenoid implant (height and inferior tilt) and use a relatively wide humeral osteotomy. The deltopectoral approach presents the advantage of exposure and liberation of the glenoid but requires a minimal humeral osteotomy and suture of the remaining subscapularis tendon at the end of surgery, due to the risk of postoperative instability.

However, the debate is not over. Advocates of the deltopectoral approach consider the use of the anterosuperior approach for difficult glenoid cases (superior or global wear), while those for the anterosuperior approach find benefit from the use of the deltopectoral approach for stiff shoulder and cases with previous surgery. As with other approaches, the anterosuperior approach requires proper positioning and knowledge of technical requirements to emphasize its advantages and minimize the risks of axillary nerve or deltoid muscle impairment.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he has no commercial association (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the Clinique de Traumatologie et d’Orthopedie.

References

- 1.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Bicknell RT, Rochet N, Trojani C. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a modified latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer for shoulder pseudoparalysis associated with dropping arm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:584–593. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005. The Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, Massin P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:516–520. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Delta III reverse shoulder arthroplasty: radiological outcome for acute complex fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chacon A, Virani N, Shannon R, Levy JC, Pupello D, Frankle M. Revision arthroplasty with use of a reverse shoulder prosthesis-allograft composite. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:119–127. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuff DJ, Virani NA, Levy J, Frankle MA, Derasari A, Hines B, Pupello DR, Cancio M, Mighell M. The treatment of deep shoulder infection and glenohumeral instability with debridement, reverse shoulder arthroplasty and postoperative antibiotics. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:336–342. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delloye C, Joris D, Colette A, Eudier A, Dubuc JE. [Mechanical complications of total shoulder inverted prosthesis] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2002;88:410–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency: a minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1697–1705. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallinet D, Clappaz P, Garbuio P, Tropet Y, Obert L. Three or four parts complex proximal humerus fractures: hemiarthroplasty versus reverse prosthesis: a comparative study of 40 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics. 1993;16:65–68. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holcomb JO, Cuff D, Petersen SA, Pupello DR, Frankle MA. Revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty for glenoid baseplate failure after primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lévigne C. Scapular notching in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, Favard L, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, editors. Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Nice Shoulder Course. Montpellier, France: Sauramps Médical; 2006. pp. 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackenzie DB. The antero-superior exposure for total shoulder replacement. Orthop Traumatol. 1993;2:71–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02620461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie DB. The antero-superior exposure for total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:S114. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(96)80486-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molé D, Favard L. [Excentered scapulohumeral osteoarthritis] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2007;93(6 Suppl):37–94. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(07)92708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neviaser JS. Surgical approaches to the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;91:34–40. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nové-Josserand L. Instability of the reverse prosthesis. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, Favard L, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, editors. Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: Nice Shoulder Course. Montpellier, France: Sauramps Médical; 2006. pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simovitch RW, Zumstein MA, Lohri E, Helmy N, Gerber C. Predictors of scapular notching in patients managed with the Delta III reverse total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:588–600. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valenti P, Sauzieres P, Cogswell L, O’Toole G, Katz D. The reverse shoulder prosthesis—surgical technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2008;12:46–55. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181572b14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1476–1486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young SW, Everts NM, Ball CM, Astley TM, Poon PC. The SMR reverse shoulder prosthesis in the treatment of cuff-deficient shoulder conditions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]