Abstract

Background/rationale

There is growing evidence that different resurfacing implants are associated with variable survival and revision rates. A registry analysis indicated the Durom resurfacing implant had high revision rates at 5 years, whereas three original studies reported low revision rates at short-term followups. Thus, the revision rates appear controversial.

Questions/purposes

We therefore assessed (1) the survivorship including differences between women and men at a mean of 5 years after resurfacing with the Durom implant, and (2) clinical scores and radiographic parameters.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively followed all 100 Durom hip resurfacings implanted in 91 patients (25 women and 66 men; mean age, 52 years) between 2003 and 2004. Survivorship analysis was performed with pending revision or revision for any reason as the endpoint. The minimum followup was 47 months (mean, 60 months; range, 47–72 months).

Results

At a mean of 5 years, 11 hips were revised for various reasons. Cumulative survival was 88.2% for all patients and 81.5% for women. The mean Oxford (OHS) and Harris hip (HHS) scores were 14.6 and 94.7, respectively. The mean UCLA activity level was 7.9. Sclerotic changes around the short femoral stem (pedestal sign) were detected in 40% of the hips. We observed considerable femoral neck thinning with component-to-neck ratios of 0.85 preoperatively and 0.82 at 5 years.

Conclusions

Our study highlights a high revision rate 5 years after hip resurfacing with the Durom implant. This observation underlines previous findings from registry data and suggests that revision rates increase with time.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) using new bearing materials was reintroduced more than one decade ago [26]. Although complications such as femoral neck fractures [37], femoral component loosening [36], and questions regarding the biologic effects of elevated metal ion levels and metal debris [10, 12, 22, 23] have become the focus of some studies, HRA is still regularly performed. This is because metal-on-metal HRA offers several conceptual advantages over conventional stem type THA, such as improved joint stability, lower volumetric wear, less femoral bone resection, and a more physiologic load transfer on the proximal femur. These features make HRA particularly interesting for younger and more active patients seeking joint replacement surgery [28, 29]. Survival rates between 94% and 100% at 4 to 7 years have been reported [8], and these results together with the conceptual features led to an escalated development of new implants by almost all orthopaedic companies. However, there is growing evidence that different HRA implants perform variably well in terms of survival and revision rates [33]. Data from the Australian Joint Registry suggest that the BHR (Smith & Nephew, London, UK) has the lowest 5-year revision rate, whereas higher rates of 8% to 10% have been reported for the ASR (DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA), Conserve Plus (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN, USA), and Cormet 2000 HAP (Corin Group, Cirencester, UK) [33]. The Durom resurfacing implant (Zimmer. Warsaw, IN, USA) had a 5-year cumulative revision rate of 6.7% [33]. Conversely, three original reports using the Durom HRA reported revisions in only 2.3% to 3.5% at a short-term followup [11, 13, 14]. The Durom resurfacing prosthesis, which differs in the design and manufacturing process from the large-diameter head metal-on-metal THA device made in the US that was associated with high failure rates [21], was launched and approved for HRA in Europe and Australia in 2003. At our institution, the Durom HRA (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) has been implanted since it became available to us.

We therefore addressed the above-mentioned controversy by (1) assessing the survivorship including differences between females and males at a mean of 5 years after surgery, and (2) assessing clinical scores and radiographic parameters.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively followed the first 91 patients who underwent 100 Durom resurfacings (25 women with 30 HRAs and 66 men with 70 HRAs, 50 left hips and 50 right hips) between June 2003 and December 2004. During the same period, there were 700 primary stem-type THAs performed at our institution. Resurfacing was indicated on an individual basis, but we usually included younger patients with an active lifestyle, good bone quality, or patients explicitly requesting HRA. We performed no HRA in patients with severe deformities of the proximal femur, such as severe valgus or varus alignment, excessive antetorsion, or severe head deformities. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 52 ± 9.9 years (range, 20–72 years). Their mean height was 173 ± 7.4 cm (range, 157–190 cm), mean weight was 77.2 ± 12.6 kg (range, 53–104 kg), and mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.7 ± 3.5 kg/m2 (range, 19.2–35.1 kg/m2). Underlying diagnoses were primary osteoarthritis (OA) in 79 hips, developmental dysplasia in nine, osteonecrosis in six, posttraumatic OA in four, and inflammatory OA in two. Patients were followed for 4 to 6 years or until failure occurred. Failure was defined as revision or pending revision for any reason. Three patients (four hips) declined to return for the 5-year followup owing to various reasons. These patients were contacted by phone to ensure they underwent no revision surgery. Baseline demographics of these three patients were similar to those for the study cohort, but their data were not included in the clinical and radiographic analyses. The minimum followup was 47 months (mean, 60 months; range, 47–72 months). The study was approved by the local ethical committee and written informed consent was obtained.

The Durom implant has a cobalt-chrome acetabular component with a titanium vacuum plasma spray coating. The cup has a wall thickness of 4 mm, a flattened pole, and a peripheral flare fin. It does not represent a full hemisphere (165°) for all sizes. The femoral components are available in 2-mm increments and match one cup size, which is always 6 mm larger.

All surgery was performed by two senior surgeons (UM, OH). In all cases, surgery was performed using a posterior approach; preoperative templating was performed. Peripheral osteophytes were removed back to the implant rim after placement of the definitive cup to assure bony coverage particularly at the anterior wall. We sequentially reamed the acetabulum in 2-mm increments up to the intended component size (ie, no underreaming). We always used trial cups. Both surgeons followed similar surgical steps, with implantation of the acetabular component after defining the minimum size of the femoral component.

All patients received perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis using a second-generation cephalosporin, and prevention of thromboembolism was through daily low-molecular-weight heparin application for 4 weeks postoperatively. No radiation or indomethacin prevention for heterotopic ossifications was administered. All patients started walking on the first postoperative day with weightbearing allowed as tolerated. Crutches were used for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. Physiotherapy, one to two times per week, was prescribed, when necessary, after 6 weeks with passive and active ROM and hip abductor strengthening exercises. At the same time, sensory-motor exercises were emphasized to promote neuromuscular control of the pelvis and lower extremity.

Followups were scheduled postoperatively at 6 weeks, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years. All complications, revisions, ROM, and HHS were prospectively determined. The German versions of the UCLA activity scale [27] and OHS [30] were administered at the last followup.

One of us (RP) evaluated femoral component and cup positions on standardized AP and lateral cross-table radiographs (preoperative neck-shaft-angle [NSA], postoperative stem-shaft-angle [SSA], cup inclination) [5]. To assess biomechanical restoration of the hip, we calculated the hip lever arm ratio (abductor moment arm divided by body moment arm) and measured the femoral offset (distance between the femoral shaft axis and the femoral head center) [5]. Heterotopic ossifications were determined according to the classification described by Brooker et al. [7]. Radiolucent lines greater than 1 mm in thickness around the acetabular cup were recorded in the three zones of DeLee and Charnley [9]. For femoral radiolucencies, we used the pedestal sign rating described by Pollard et al. [32]. Femoral neck narrowing was determined by comparing the neck to prosthesis ratios seen on the first postoperative radiographs with those seen on radiographs obtained at the last followup [35]. Radiographic data of the revision cases were obtained from the last followup, before the revision.

Survivorship was calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method with pending revision or revision for any reason as the endpoint. Survivorship was compared between female and male patients using the log-rank test. The four hips without complete followup data were eliminated from the study at the time of their last clinical and radiographic followup; at the time of last followup none of these four hips had recognized complications and none had been revised. Differences between preoperative and postoperative HHS, ROM, and radiographic parameters were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests after testing for normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk W test). Unless otherwise stated, all values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 14, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

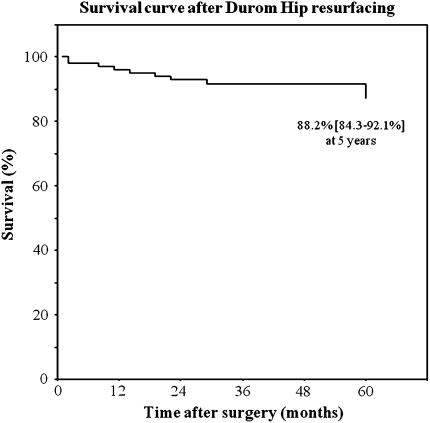

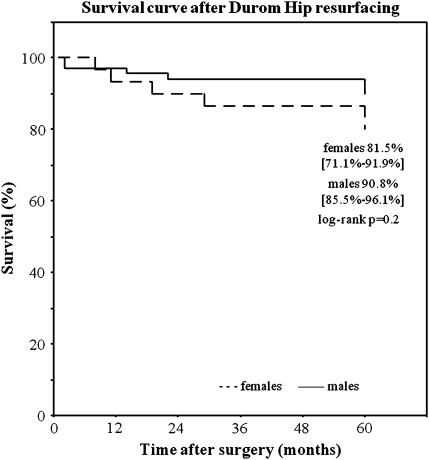

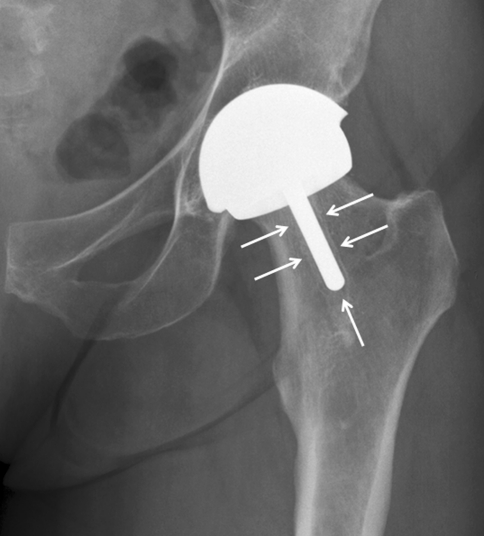

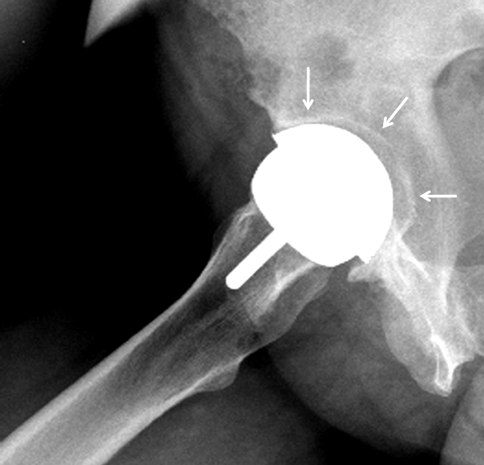

Survival at 5 years with revision or pending revision for any reason as the endpoint was 88.2% for all patients (95% CI = 84.3%–92.1%) (Fig. 1), 81.5% for women (95% CI = 71.1%–91.9%), and 90.8% for men (95% CI 85.5%–96.1%) (Fig. 2). Nine revision surgeries were performed during the first 5 years. Two hips had signs of clinical and/or radiographic failure and underwent revision owing to femoral component loosening 64 and 68 months after HRA. Overall, revisions were necessary in 16.7% of women and 8.6% of men (Table 1). Four patients had femoral neck fractures, two had femoral loosening (Fig. 3), one had cup loosening (Fig. 4), two had impingement, and two had persistent pain. We found no differences between patients who had revision surgery and those who did not have revision surgery in terms of age, height, weight, BMI, ROM, head size, cup inclination, and SSA. No pseudotumors occurred in this cohort.

Fig. 1.

The graph shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve with revision or pending revision for any reason as the endpoint. Cumulative survival at 5 years was 88.2% (95% CI = 84.3%–92.1%) for all patients.

Fig. 2.

The graph shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve with revision or pending revision for any reason as the endpoint. Cumulative survival at 5 years was similar (log-rank, p = 0.2) for women and men: 81.5% (95% CI = 71.1%–91.9%) and 90.8% (95% CI 85.5%–96.1%), respectively.

Table 1.

Revisions after Durom hip resurfacing

| Patient number | Gender/age (years) | Reason for revision | Time after HRA (months) | Femoral component size (mm) | Intraoperative findings | Procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cup | Femoral component | Joint | Metallosis | ||||||

| 1 | M/55 | Neck fracture | 2 | 50 | Stable | Fracture at head neck junction | Normal | None | Stem THA with large metal head |

| 2 | M/37 | Neck fracture | 2 | 46 | Stable | Fracture at head neck junction | Normal | None | Stem THA with large metal head |

| 3 | W/48 | Persistent pain | 8 | 44 | Stable | Stable | Much effusion, severe synovitis | Moderate | Cup and stem revision, PE inlay, Cr head |

| 4 | W/36 | Neck fracture | 11 | 44 | Stable | Fracture at head neck junction | Slight effusion | Slight | Stem THA with large metal head |

| 5 | M/53 | Neck fracture | 14 | 52 | Stable | Fracture at head neck junction | Normal | None | Stem THA with large metal head |

| 6 | W/48 | Cup loosening | 19 | 46 | Loose | Stable | Much effusion, moderate synovitis | Slight | Cup reimplantation, removal of posterior osteophytes |

| 7 | M/47 | Impingement | 22 | 48 | Stable | Stable | Slight effusion | Slight | Neck osteoplasty |

| 8 | W/50 | Impingement | 29 | 52 | Stable | Stable | Much effusion | Moderate | Neck osteoplasty |

| 9 | M/53 | Persistent pain | 56 | 52 | Stable | Stable | Slight synovitis | None | Stem-THA with large metal head |

| 10 | W/59 | Femoral loosening | 64* | 42 | Stable** | Loose | Much effusion | Severe | Cup and stem revision, PE inlay, Cr head |

| 11 | M/41 | Femoral loosening | 68* | 48 | Stable | Loose | Slight effusion | None | Stem THA with large metal head |

PE = polyethylene; Cr = ceramic; M = men; W = women; *pending revision at the 5-year followup; **stable on initial testing but easily removable during exchange.

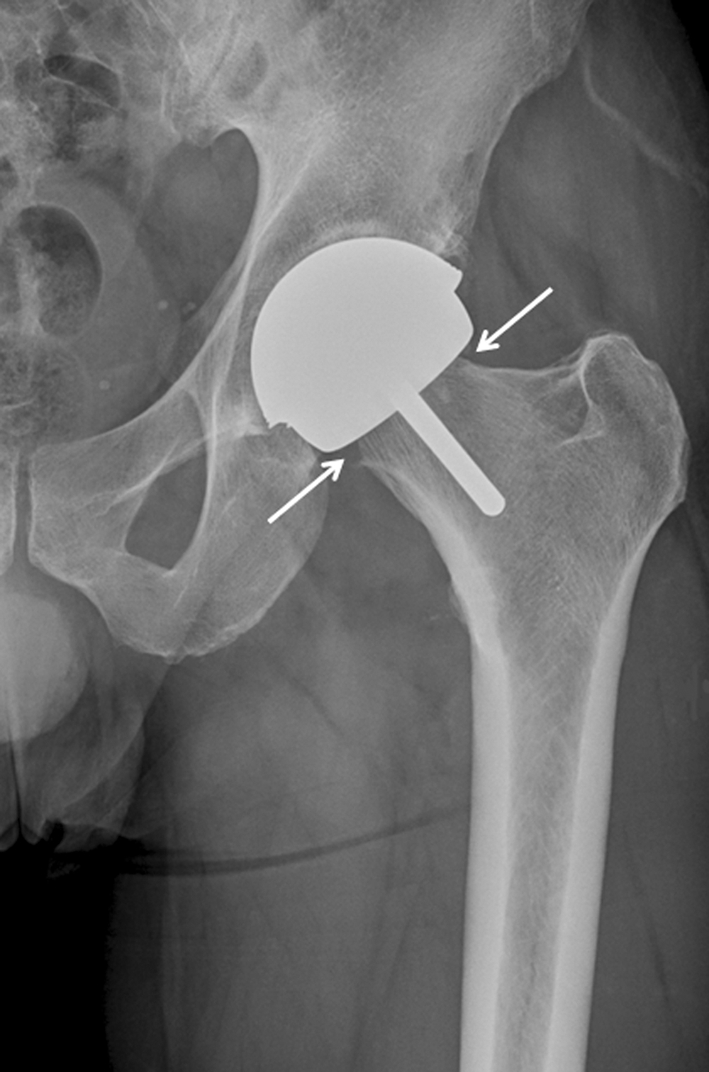

Fig. 3.

The radiograph of a female patient (Patient 10, Table 1) with femoral loosening shows a radiolucent line surrounding the entire femoral stem (white arrows). The patient had revision surgery 4 months later.

Fig. 4.

The radiograph of a female patient (Patient 6, Table 1) with cup loosening shows a radiolucency surrounding the entire cup (white arrows). The patient underwent revision surgery 19 months after HRA.

Clinically, ROM and HHS were improved (Table 2). Radiographically, the SSA of the femoral component was 135.7° ± 7.4° (range, 115.0° to 155.9°) compared to a preoperative NSA of 129.6° ± 6.3° (range, 113.6° to 150.9°) (p < 0.001). The mean cup inclination was 45.4° ± 8.4° (range, 30°–70.8°). The femoral offset remained unchanged (p = 0.06): a mean of 48.9 mm preoperatively versus 50.4 mm postoperatively. Hip lever arm ratios increased (p < 0.001) from 0.59 ± 0.08 (range, 0.40–0.79) to 0.62 ± 0.08 (range, 0.43–0.80). Heterotopic ossifications were seen in 22 of the 96 hips (22.9%) followed until failure or until the last followup (16 [16.7%] Grade I, five [5.2%] Grade II, and one [1%] Grade III). Acetabular radiolucencies in zone I were detected in two hips (2.1%), in zone II in five hips (5.2%), and in both zones in another five hips (5.2%). The one hip revised for cup loosening had radiolucencies in all three zones. A type I pedestal sign, corresponding to a sclerotic line around the tip of the femoral component was detected in 34 of the hips (35.4%), a type IIa was seen in one hip (1%), and a type III (radiolucency surrounding the entire short stem) was seen in four hips (4.2%). All hips with a type III pedestal sign underwent revision. The prosthesis-to-neck ratio decreased (p < 0.001) from 0.85 ± 0.04 (range, 0.74–0.96) to 0.82 ± 0.05 (range, 0.61–0.92). A decrease of the ratio exceeding 10% (Fig. 5) was seen in eight hips (8.3%).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes 5 years after Durom hip resurfacing

| Outcome variable | Preoperative | Followup | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harris hip score | 57.9 ± 12.0 | 94.7 ± 5.9 | p < 0.0001 |

| Oxford hip score | 14.6 ± 3.4 | ||

| UCLA activity level | 7.9 ± 1.6 | ||

| Flexion (°) | 90.3 ± 13.5 | 99.8 ± 8.4 | p < 0.0001 |

| Internal rotation (°) | 4.9 ± 6.9 | 12.8 ± 9.1 | p < 0.0001 |

| External rotation (°) | 18.6 ± 13.6 | 29.7 ± 9.7 | p < 0.0001 |

| Abduction (°) | 26.3 ± 10.6 | 39.0 ± 10.5 | p < 0.0001 |

| Adduction (°) | 16.4 ± 8.7 | 25.4 ± 8.4 | p < 0.0001 |

Fig. 5.

Substantial femoral neck thinning 5 years after HRA is evident on this radiograph. The patient was doing well at the 5-year followup.

In three hips, an undisplaced fracture of the acetabular rim occurred while seating the cup. These patients were mobilized with partial weightbearing of half their body weight for 4 weeks postoperatively. None of these hips was revised until the last followup. A temporary hypoesthesia of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve occurred in one patient that resolved within 6 weeks.

Discussion

Results from nationwide registries indicated different HRA implants performed variably well in terms of survival and revision rates [33]. Data from the Australian Joint Registry suggest that the Durom resurfacing implant had a 5-year cumulative revision rate of 6.7% [33]. Conversely, three original reports using the Durom HRA reported revisions in only 2.3% to 3.5% at a short-term followup [11, 13, 14]. We used the Durom HRA since its became available to us and in the current study, we addressed the above-mentioned controversy by (1) assessing the survivorship (with pending revision or revision for any reason as the endpoint) including differences between females and males at a mean of 5 years after surgery, and (2) assessing clinical scores and radiographic parameters.

Before interpreting the following results, several limitations must be considered. First, we have no information regarding histologic analyses of the revised components, which could partially explain some of the failure patterns. Second, some outcome scores were determined only at the final followup, because these measures previously were unavailable in German [27, 30]. Third, three patients (four hips) were lost before the final followup. Although we tried to overcome this limitation by contacting these patients by phone to ensure they underwent no revision surgery, any pending revision (ie, radiographic signs of loosening) could not be assessed. Finally, we investigated only one implant, so our results do not allow for conclusions regarding the superiority of any HRA prosthesis.

We found a 5-year survival rate of the Durom HRA of 88.2% with revision or pending revision for any reason as the endpoint. Eleven of the 100 patients had to undergo revision surgery owing to various reasons, but mainly related to the femoral component. Based on the results of the Australian Joint Registry, Prosser et al. [33] showed that revisions after Durom HRA increased from 3% at 2 years, to 4.7% at 3 years, and to 6.7% (95% CI 4.7–9.7%) at 5 years. Three previous studies also investigated the Durom HRA, and all three reported lower revision rates ranging from 2.3% to 3.5% [11, 14, 15]. Gravius et al. [13, 14] reported on two series of 59 and 82 cases with mean followups of 25 and 29 months, respectively. They performed revision surgeries owing to one femoral neck fracture and one Brooker Grade III ossification, and another revision was recommended for impingement at the head-neck junction, but was not performed [13, 14]. A larger series with 134 hips was reported by Goronzy et al. [11]. They reported three revisions (2.3%) at a mean followup of 29 months; one femoral neck fracture, one femoral loosening, and one septic loosening [11]. Overall, the failure modes observed in our study are well known and were proportionally similar to those reported from national registries (Australia, England-Wales, Sweden): femoral neck fracture accounted for 37% of the revisions, component loosening for 27%, persistent pain for 18%, and impingement for 18% [8]. Also in line with other studies, female patients had an increased failure risk; revisions were necessary in 17% of women after 5 years [3, 18]. However, in contrast to previous findings, smaller femoral head size was not associated with an increased risk for revision, at least after 5 years [3, 33, 34]. We assume that these differing results in terms of revision rates are related mainly to the followup time, as shown by the registry data [33]. Although complications such as femoral neck fractures occur relatively early after surgery, revisions attributable to loosening may be required later. The latest revisions in our series were loosening related. Unfortunately, we cannot draw valid conclusions in comparison with other HRA implants as our series focused only on the Durom prosthesis. However, better outcomes in terms of failure or revision have been reported for the BHR; 4- to 7-year survival rates varied between 94% and 100% [15, 16, 24, 31, 32, 38, 39]. The data from the Australian Joint Registry also suggested that the BHR has the lowest 5-year revision rate of all devices compared [33]. Future comparative studies with adequate followup are warranted to identify possible superiority of any HRA implant.

The clinical results in terms of ROM, hip scores, and activity levels compared well with those reported by others [15, 16, 24, 31, 32, 38, 39]. Radiographically, sclerotic changes around the short femoral stem (pedestal sign) were detected in 40% of the hips, which is less than the 60% reported by Pollard et al. [32]. However, the clinical relevance of these changes, as long as they remain localized around the stem’s tip, are unknown [32]. More important might be the occurrence of femoral neck thinning [17, 19, 35]. The ratios reported by Spencer et al. (0.87 preoperatively, 0.81 postoperatively) [35] are largely the same as those observed in our study (0.85 and 0.82, respectively). Although a relation between femoral neck thinning and failure has not been proven, the two hips with femoral loosening in our series had prosthesis-neck ratios reduced by 23% and 17% before revision. One explanation for narrowing of the neck might be a compromised blood supply. There is increasing evidence that the posterior approach (most frequently used for HRA) and preparation of the proximal femur can impair the blood supply to the femoral head [2, 4, 6, 20]. Studies comparing neck narrowing after HRA with different approaches (eg, the posterior approach and the surgical hip dislocation) would be of interest, considering that progressive neck thinning might lead to later complications.

Eleven revisions in 100 hips were required at a mean of 5 years after HRA with the Durom implant, corresponding to a survival rate of only 88.2%. Women had an even higher revision rate of 17%. Progressive femoral neck thinning was observed frequently which might lead to additional future problems. Although most of the revisions performed in our series could not be attributed directly to the implant, we stopped using the Durom prosthesis for HRA. We presumed a combination of factors such as the surgical approach diminishing the blood supply to the proximal femur, implant characteristics related to tribology and fixation, and implantation technique were responsible for the high revision rate. Considering the aforementioned, standard THA using established implants is as an excellent treatment option, even for younger patients with hip OA [1, 25].

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Kampmann MD for help with data preparation and Thomas Guggi MD for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Aldinger PR, Jung AW, Pritsch M, Breusch S, Thomsen M, Ewerbeck V, Parsch D. Uncemented grit-blasted straight tapered titanium stems in patients younger than fifty-five years of age: fifteen to twenty-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1432–1439. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarasekera HW, Costa ML, Foguet P, Krikler SJ, Prakash U, Griffin DR. The blood flow to the femoral head/neck junction during resurfacing arthroplasty: a comparison of two approaches using Laser Doppler flowmetry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:442–445. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amstutz HC, Beaulé PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Campbell PA, Gruen TA. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty: two to six-year follow-up study. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:28–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaulé PE, Campbell P, Shim P. Femoral head blood flow during hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;456:148–152. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238865.77109.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaule PE, Dorey FJ, LeDuff M, Gruen T, Amstutz HC. Risk factors affecting outcome of metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:87–93. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaulé PE, Ganz R, Leunig M. Blood flow to the femoral head and hip resurfacing arthroplasty][in German. Orthopade. 2008;37:659–666. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1300-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH., Jr Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement: incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1629–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corten K, MacDonald SJ. Hip resurfacing data from national joint registries: what do they tell us? What do they not tell us? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:351–357. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1157-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glyn-Jones S, Pandit H, Kwon YM, Doll H, Gill HS, Murray DW. Risk factors for inflammatory pseudotumour formation following hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1566–1574. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B12.22287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goronzy J, Stiehler M, Kirschner S, Günther KP. [Durom™ hip resurfacing: short- to midterm clinical and radiological outcome] [in German] Orthopade. 2010;39:842–852. doi: 10.1007/s00132-010-1656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grammatopolous G, Pandit H, Kwon YM, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Beard DJ, Murray DW, Gill HS. Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1019–1024. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravius S, Mumme T, Weber O, Berdel P, Wirtz DC. Surgical principles and clinical experiences with the DUROM hip resurfacing system using a lateral approach][in German. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2009;21:586–601. doi: 10.1007/s00064-009-2007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravius S, Wirtz D, Maus U, Andereya S, Müller-Rath R, Mumme T. Durom hip resurfacing arthroplasty: first clinical experiences with a lateral approach][in German. Z Orthop Unfall. 2007;145:461–467. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilpern GN, Shah NN, Fordyce MJ. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a series of 110 consecutive hips with a minimum five-year clinical and radiological follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1137–1142. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hing CB, Back DL, Bailey M, Young DA, Dalziel RE, Shimmin AJ. The results of primary Birmingham hip resurfacings at a mean of five years: an independent prospective review of the first 230 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1431–1438. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.19336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hing CB, Young DA, Dalziel RE, Bailey M, Back DL, Shimmin AJ. Narrowing of the neck in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1019–1024. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.18830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jameson SS, Langton DJ, Natu S, Nargol TV. The influence of age and sex on early clinical results after hip resurfacing: an independent center analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 suppl 1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph J, Mullen M, McAuley A, Pillai A. Femoral neck resorption following hybrid metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a radiological and biomechanical analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1433–1438. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1070-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan A, Lovering AM, Bannister GC, Spencer RF, Kalap N. The effect of a modified posterior approach on blood flow to the femoral head during hip resurfacing. Hip Int. 2009;19:52–57. doi: 10.1177/112070000901900110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long WT, Dastane M, Harris MJ, Wan Z, Dorr LD. Failure of the Durom Metasul acetabular component. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:400–405. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabilleau G, Kwon YM, Pandit H, Murray DW, Sabokbar A. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a review of periprosthetic biological reactions. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:734–747. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahendra G, Pandit H, Kliskey K, Murray D, Gill HS, Athanasou N. Necrotic and inflammatory changes in metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:653–659. doi: 10.3109/17453670903473016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBryde CW, Revell MP, Thomas AM, Treacy RB, Pynsent PB. The influence of surgical approach on outcome in Birmingham hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:920–926. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaughlin JR, Lee KR. Total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented tapered femoral component in patients younger than 50 years. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMinn D, Treacy R, Lin K, Pynsent P. Metal on metal surface replacement of the hip: experience of the McMinn prothesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329(suppl):S89–S98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Leunig M. Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:958–965. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naal FD, Maffiuletti NA, Munzinger U, Hersche O. Sports after hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:705–711. doi: 10.1177/0363546506296606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naal FD, Schmied M, Munzinger U, Leunig M, Hersche O. Outcome of hip resurfacing arthroplasty in patients with developmental hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1516–1521. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naal FD, Sieverding M, Impellizzeri FM, Knoch F, Mannion AF, Leunig M. Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted German Oxford hip score. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:952–957. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0457-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ollivere B, Darrah C, Barker T, Nolan J, Porteous MJ. Early clinical failure of the Birmingham metal-on-metal hip resurfacing is associated with metallosis and soft-tissue necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1025–1030. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.21701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollard TC, Baker RP, Eastaugh-Waring SJ, Bannister GC. Treatment of the young active patient with osteoarthritis of the hip: a five- to seven-year comparison of hybrid total hip arthroplasty and metal-on-metal resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:592–600. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B5.17354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prosser GH, Yates PJ, Wood DJ, Graves SE, Steiger RN, Miller LN. Outcome of primary resurfacing hip replacement: evaluation of risk factors for early revision. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:66–71. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimmin AJ, Walter WL, Esposito C. The influence of the size of the component on the outcome of resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:469–476. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B4.22967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spencer S, Carter R, Murray H, Meek RM. Femoral neck narrowing after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:1105–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Springer BD, Connelly SE, Odum SM, Fehring TK, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Masonis JL. Cementless femoral components in young patients: review and meta-analysis of total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steffen RT, Foguet PR, Krikler SJ, Gundle R, Beard DJ, Murray DW. Femoral neck fractures after hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffen RT, Pandit HP, Palan J, Beard DJ, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Murray DW, Gill HS. The five-year results of the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing arthroplasty: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:436–441. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.19648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treacy RB, McBryde CW, Pynsent PB. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty: aminimum follow-up of five years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:167–170. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B2.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]