Abstract

Background

The increased use of the reverse prosthesis over the last 10 years is due to a large series of publications using the reverse prosthesis developed by Paul Grammont. However, there is no article reporting the story of the concepts developed by Grammont.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this review are to describe the principles developed by Grammont, the chronology of development, and the biomechanical concepts and studies that led to the current design of the reverse prosthesis.

Methods

We selectively reviewed literature and provide personal observations.

Results

From phylogenetic observations, Grammont developed the principle of functional surgery applied to the rotator cuff tears. To increase the deltoid lever arm, he imagined two possibilities: the lateralization of the acromion, which facilitates the action of the rotator cuff, and the medialization of the center of rotation, which has been developed to respond to situations of rotator cuff deficiency. Grammont proposed the use of an acromiohumeral prosthesis, which was quickly abandoned due to problems of acromial loosening. Finally, Grammont used the principle of reverse prosthesis developed in the 1970s, but made a major change by medializing the center of rotation in a nonanatomic location. In 1985, Grammont validated the concept by an experimental study and the first model using a cemented sphere was implanted.

Conclusions

The development of the modern reverse prosthesis is the result of the intellectual and experimental work conducted by Grammont and his team for 20 years. Knowledge of this history is essential to envision future developments.

Introduction

A classical way of telling a story would be to start with the key dates. However, in the case of the Paul Grammont prosthesis, if one is to be loyal to the original inventor of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty and his rare intuition, it is essential to also acknowledge the thought process, over more than 10 years, that gave birth to his concept of “functional surgery” as applied to the shoulder. This process also produced the mechanical specifications and original design rationale for the prosthesis that bears his name.

We therefore describe the principles developed by Grammont, the chronology of development, and the biomechanical concepts and studies that led to the current design of the reverse prosthesis.

What Were Grammont’s Thoughts?

Thanks to his extensive study of comparative anatomy and the evolution of morphology, Grammont explained the mechanical failure of the shoulder in modern humans [19]. During evolution, the acquisition of a permanently erect posture would free the human shoulder of its quadruped functions, and the anterior limb—becoming the upper limb—would eventually be expected to perform new skills that, according to Grammont, would exceed human anatomic capacities.

During the acquisition of upright posture, two major modifications are worth emphasizing. First, at the level of the supraspinatus-deltoid muscular couple, a relative atrophy of the supraspinatus occurred, as illustrated by a decreased scapular index, calculated according to Pearl and Schultz [33] (ratio between the depths of the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus fossae). At the same time, the supraspinatus’ decreased effectiveness was compensated for by the lateralization of the acromion and hence of the deltoid’s middle abduction zone (as defined by Fick [14] in 1911), which strengthened the deltoid abduction component. However, for Grammont, the supraspinatus was not the only loser in this evolutionary process because, when the balance was tipped to its detriment, that led to the mechanical failure of the whole system [19]. From this first analysis, Grammont designed his original Translation-Rotation-Elevation osteotomy of the scapula spine in 1975 [5, 19, 22, 24]. The acromion’s lateralization resulted in an increase of the deltoid’s abduction component while decreasing its elevation component, easing the recruitment of the rotator cuff—an effect confirmed by Blaimont et al. [10]. He later put precisely this principle into practice, not by lateralizing the acromion, but by medializing the joint’s center of rotation (COR) [21]. The outcome was similar: an increase of the deltoid lever arm (Figs. 1, 2).

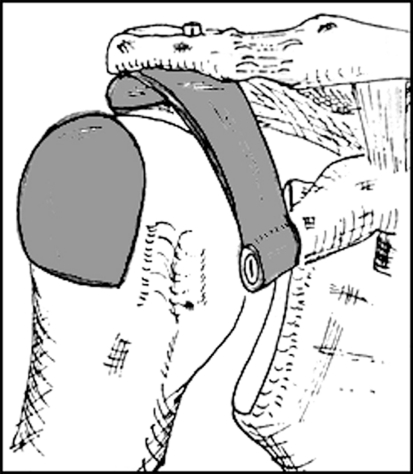

Fig. 1.

An original diagram from Paul Grammont shows the “medializing” prosthesis design. His first idea was to propose a varus position of the humeral head to medialize the COR and to increase the deltoid lever arm. A rotating system has been imagined at the junction between the stem and the neck of the prosthesis. Image from the personal archives of Emmanuel Baulot. COR = center of rotation.

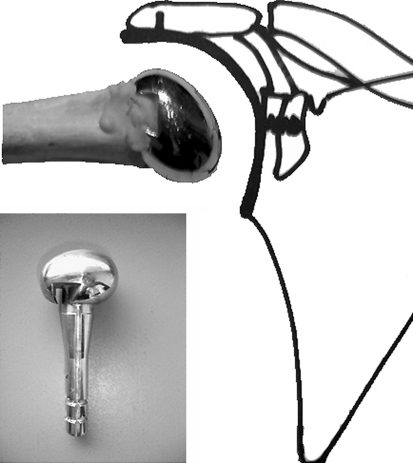

Fig. 2.

A photograph shows the first prototype of the “medializing” prosthesis. This prototype was based on the drawing of Grammont but does not include the metaphyseal rotation system. The stem was screwed. This prototype was never implanted. Image from the personal archives of Emmanuel Baulot.

Second, the quadruped humerus, formerly the carrier of the glenoid, became a biped humerus, now carried by the glenoid. Thus, the freeing of the human upper limb resulted in a functional reversal of the roles of the humerus and the glenoid. The notion of a morphologic role reversal also began to appear at this point.

The purpose of functional surgery, as conceived by Grammont, is to allow the shoulder to exert the function required by the person in his/her environment. The state of the periarticular soft tissues is certainly one of the most important factors influencing the fate of shoulder prosthetic surgery. Thus, starting from the observation that there was no effective anatomic prosthetic solution without anatomic repair of the torn cuff, it was time to propose the possibility of breaking free of anatomy and searching for the restoration of effective function through a novel morphology.

Grammont liked to repeat the following statement: “The patient who has lost a function doesn’t care about the design of the prosthesis that will be implanted but only about its effectiveness in restoring the lost function. It is useless to search for an anatomic solution, as this very anatomic system led to failure” [verbal communication, P. Grammont]. This idea, a complete break with the traditional wisdom of anatomic restoration, had some difficulty in gaining ground, as in 1995, Grammont wrote: “We have been blamed for having treated some of our cuff tear arthropathy cases with a reversed prosthesis. But, some years ago, around 1985, what else could be done?” [written communication, P. Grammont].

Chronology and Developments

In the early 1980s, a unanimous observation prevailed: it was extremely difficult, or even impossible, to obtain a functionally good result with prosthetic arthroplasty in cases of osteoarthritis associated with a rotator cuff deficiency. C. S. Neer himself talked of “limited goals surgery” [29]. It is essential to note the consistency of the failure of surgery to durably relieve pain and/or restore function despite the different prostheses used to treat osteoarthritis with rotator cuff tear: hemiarthroplasty [2, 34, 36, 38, 39], anatomic total arthroplasty [3, 16, 27], and first-generation reversed prostheses (Kölbel and Friedebold [28] in Germany, Gérard et al. [18] in France, both reported in 1973). Hemiarthroplasty provided satisfactory pain relief but poor gain in motion [2, 34, 36, 38, 39]. The main complication associated with total unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty was early loosening of the glenoid component [3, 16, 27]. The use of the first generation of reverse shoulder prosthesis was discontinued because of loosening and mechanical complications [18, 28]. The COR of these early reversed prostheses was more lateralized than in the anatomic prosthesis, far away from the glenoid plane and in the axis of the adducted humerus. In this context, the first solution found by Grammont and Lelaurain [22] in 1977 had been the “Acropole” prosthesis (Medinov®, Roanne, France) (Fig. 3), which created a subacromial joint to resurface and use the subacromial space “freed by the cuff tear” to oppose the upward migration of the head and center it back in front of the glenoid. The resurfacing effect did eradicate the pain, but the functional efficiency was only barely or not at all improved [22]. Due to the early loosening of the glenoid component and secondary coracoacromial arch impingement, it was abandoned as early as 1981.

Fig. 3.

A diagram from Paul Grammont illustrates the “Acropole” prosthesis. This prosthesis used the principle of an acromiohumeral resurfacing. About 20 such prostheses were implanted by Grammont. Most of them had acromial component loosening. Image from the personal archives of Emmanuel Baulot.

So, the problem remained unsolved! The conclusion, inevitably, was that failures were resulting, not from the specific prosthetic designs, but from their common mechanism: the inability to counter the deltoid’s subluxating effect in the absence of the cuff.

The challenge of finding a compromise among mobility, stability, mechanical efficiency, and resistance to loosening was considered impossible. Strengthened by his comparative anatomy arguments, the clinical improvement reported after his scapula spine osteotomy [5, 22, 24], and following the work of Fischer et al. [15] on the COR of the physiologic shoulder, Grammont pinpointed the importance of the relationship between the balance of the supraspinatus-deltoid couple and the position of prosthesis’ COR. At the time, his proposal for restoring this functional loss was an original marriage of an innovative mechanical principle with an optimal use of the deltoid in the absence of the cuff. Grammont’s favorite comparison here was of “functional surgery” with anatomic “damage surgery,” which by definition cannot provide a solution. Applying the principles of moments to all the existing prostheses allows one to understand immediately their common mechanical flaw: the weakness of the abduction lever arm of the middle deltoid.

The Mechanical Concept Statement

The above original mechanical concept was then demonstrated with a strictly theoretical mathematical approach in 1981 by two engineers under the direction of Grammont in a report entitled Study of a Mechanical Model for a Shoulder Total Prosthesis: Realization of a Prototype [21]. Grammont’s conclusion was, when the cuff is absent, the solution is to intrinsically balance the middle deltoid to strengthen its abduction component and lessen the elevation component responsible for loosening stress on the glenoid. Regarding the COR, he wrote: “medializing the COR of the scapulohumeral joint, and so increasing the deltoid lever arm, will compensate for the lack of activity of the supraspinatus muscle. In this way, we would move the mobile joint against the scapula without allowing a change in the position of the humerus in reference to the scapula. Indeed, if at the same time, we medialized the humerus itself, the deltoid lever arm would remain unchanged instead of being increased… In a first step, we’ll have to lower the center of rotation” [21]. The original mechanical concept of medializing the COR was born, thus defining the specifications for a real “cuff prosthesis,” which had yet to be developed!

The above method of strengthening the deltoid abduction component was consistent with, and validated by, the experience of the Translation-Rotation-Elevation osteotomy of the scapular spine, described in 1975 [24]. After all, the increase of the middle deltoid lever arm induced by the acromial lateralization through this osteotomy was real and measurable [24]. Therefore, the deltoid can be affected in the same way by two different means: lateralizing the acromion without moving the COR or medializing the COR without moving the acromion!

With the first prototype (Fig. 2), the departure from the anatomic design was not yet complete. It looked like a hip prosthesis with two components: a humeral metaphysioepiphyseal component with a very small head and a real neck to both medialize the COR and maintain the lateral position of the humerus. This component was inserted in a diaphyseal stem thanks to an axis allowing a rotation in the prosthesis. This first prototype was never implanted. The first implanted medializing prosthesis followed later. The “Ovoide” prosthesis (Medinov®), introduced in 1980, was the first to truly break the link with anatomy (Fig. 4). While that device effectively strengthened the middle deltoid, it was persistently unstable [22].

Fig. 4.

The “Ovoide” prosthesis is shown. This prosthesis has theoretically two CORs. It obtained medialization by early elevation. Approximately 10 such prostheses were implanted, but it was abandoned because of problems of instability. Image from the personal archives of Emmanuel Baulot. COR = center of rotation.

The Modern Reverse Design: Experimental Simulation of the System

From that point, supported by his mechanical-medialization principle on the one hand and his studies on comparative anatomy on the other (elucidating the evolution of the quadruped humerus, carrier of the glenoid, into the biped humerus, carried by the glenoid), Grammont proposed adapting the principle of medialization to the reverse design previously used during the 1970s. This breach with anatomy, complete and rude, was the real revolution.

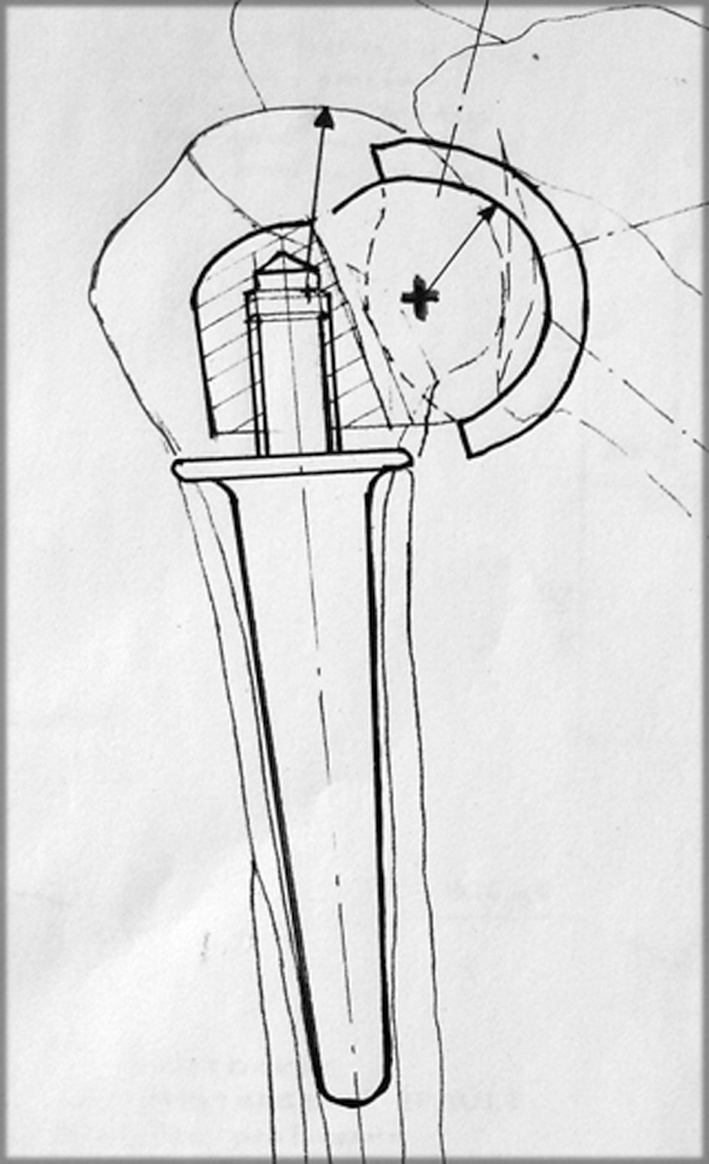

This prototype was manufactured in 1985 and called the “Trompette” (Medinov®) (Fig. 5). It was composed of a glenoid component, consisting of 2/3 of a 44-mm-diameter sphere, with its COR set in a specific, medialized location facing the glenoid. This ceramic glenoid component was cemented onto the glenoid. On the humeral side, a concave, monoblock polyethylene cone was also cemented. This prototype was tested and validated according to a Strasser-like experimental model by Deries [12], described in his graduate thesis A Biomechanical Approach to Study the Effects of a Modification of the Rotation Center of a Shoulder Prosthesis on the Deltoid Strengths During the Abduction Movement in 1986. Furthermore, this design produced an additional lowering of the COR, which complemented the medialization effect.

Fig. 5.

The “Trompette” reverse prosthesis is shown. This is the modern version of the “medializing” reverse prosthesis as Grammont had imagined. The prototype dates from 1985 and the first implantation was in 1986. This prosthesis included a polyethylene humeral component and an alumina ceramic glenoid component with a volume equivalent to 2/3 of a sphere of 44 mm. Image from the personal archives of Emmanuel Baulot.

In 1987, Grammont reported the first eight cases operated with the Trompette prosthesis in salvage situation. Three of them achieved between 100° and 130° of elevation at 6 months despite preoperative rotator cuff deficiency [23]. Later, Grammont and his collaborators observed loosening of the cemented large sphere (2/3 of sphere) and they moved to a press-fit glenoid baseplate with a smaller hemisphere (personal observations). Nonetheless, some of these early Grammont reverse prostheses are still surviving at more than 15 years of followup. Notably, this Trompette prosthesis has been associated only with small and nonprogressive notches on the scapular pillar (personal observations).

Successive improvements followed. The first generation of a modular prosthesis called the Delta III (Medinov®) arrived in 1991 [6, 7, 20]. It was composed of five components: a glenoid baseplate fixed with two diverging polar screws and two equatorial screws, with a glenoid hemisphere, a polyethylene cup, a humeral metaphysis, and a humeral diaphysis. It was modified in 1995, the peripheral screwed fixation of the sphere on the glenoid baseplate becoming a central one. The choice of a large humeral stem (which looked massive on radiographs) came from the idea developed in hip arthroplasty of maximizing the contact area between the stem and the host bone.

Discussion

The modern reverse prosthesis as it was developed by Grammont is the achievement of an intellectual process conducted for 20 years by Grammont and his team. The reasoning of Grammont was marked by several stages from concept to prototype development, testing, and biomechanical and clinical applications. Few references are available concerning this subject and this synthesis with his collaborators will pay tribute to the original and pioneering work conducted by Grammont.

To resolve the problem of the rotator cuff deficiency, Grammont proposed two solutions to improve the deltoid abductor component: the lateralization of the acromion and the medialization of the COR. From anatomic comparative studies, Grammont hypothesized a relationship between the position of the acromion and the rotator cuff function. For him, the lateralization of the acromion can increase the abductor component of the acromion and decrease the ascending force component, facilitating the intact rotator cuff function. Nyffeler et al. [32] and Torrens et al. [37] showed later there was a relationship between the lateralization of the acromion and the rotator cuff tear. For Nyffeler et al. [32], this relationship is linked to reduced compressive forces by the medial deltoid when the acromion is lateralized. This compressive force component has a stabilizing effect on the humeral head as shown by Gagey and Hue [17] in a biomechanical model and an anatomic study on cadavers [9]. Grammont had already taken account of the importance of centering the humeral head as he developed the Acropole prosthesis for shoulder arthritis with deficient rotator cuff. However, due to the problems of acromial implant loosening, the system has been abandoned. In fact, the prosthetic head with a lateral extension developed for cuff tear arthropathy resumed in some way the principle of acromiohumeral arthroplasty developed by Grammont [4].

The medialization of the COR is the second principle developed by Grammont. He first tried to medialize the prosthetic head relative to the diaphyseal axis as in a hip arthroplasty, but he soon realized the solution of a constrained prosthesis reproducing the anatomy was doomed to failure. The Ovoide prosthesis was the first step toward a “nonanatomic” solution for medializing the COR, but the application of medialization of the rotation center combined with the “reverse” design supported in the 1970s represents the deep thoughts of Grammont’s principles. Several studies have shown medialization of the rotation center substantially increases the deltoid lever arm with the ability to restore glenohumeral mobility in elevation when a rotator cuff tear is absent [8, 13, 26]. Moreover, the power exerted by the deltoid muscle is increased by the restoration of muscle tension due to the lowering of the humerus [11]. The medialization of the COR leads to more concentric forces at the prosthesis-bone junction in the early degrees of elevation. It allows stable fixation of the glenoid baseplate, as has been confirmed in long-term clinical studies [25] or analysis of explanted prostheses [31]. The biomechanical study from Ahir et al. [1] confirmed uncemented fixation is better than cemented in reverse-design prostheses. The disadvantage of medialization is the occurrence of a potential impingement responsible for a scapular notch. Several studies show lateralization of the COR increases mobility and decreases the risk of impingement [26, 30, 35], but the design of these prostheses is far away from the principle of medialization defended by Grammont.

Although doubts and suspicion were raised initially regarding the translation of the original mechanical principle of medialization into the idea of a reversed prosthesis, it eventually succeeded in imposing itself and proving its effectiveness, becoming an essential part of shoulder prosthetic surgery. Despite the current keen interest in the reversed prosthesis, one must not forget some problems remain unsolved: first, scapular notching and humeral bone loss, and second, on the functional level, the persistent difficulty in recovering external and internal rotation. There is still much work to be done!

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

This work was performed at Clinique de traumatologie et d’orthopédie.

References

- 1.Ahir SP, Walker PS, Squire-Taylor CJ, Blunn GW, Bayley JI. Analysis of glenoid fixation for a reversed anatomy fixed-fulcrum shoulder replacement. J Biomech. 2004;37:1699–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arntz CT, Jackins S, Matsen FA., 3rd Prosthetic replacement of the shoulder for the treatment of defects in the rotator cuff and the surface of the glenohumeral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:485–491. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA., 3rd Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:865–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basamania C. Hemiarthroplasty for cuff tear arthropathy. In: Zuckermann JD, ed. Advanced Reconstruction—Shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2007:567–578.

- 5.Baulot E, Cavaillé A, Grammont PM. Translation-rotation osteotomy of the spine of the scapula for treatment of impingement syndrome and incomplete cuff tears. Eur J Orthop Surg Trauma. 1993;3:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baulot E, Chabernaud D, Grammont PM. Results of Grammont’s inverted prosthesis in omarthritis associated with major cuff destruction: report of 16 cases [in French] Acta Orthop Belg. 1995;61:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baulot E. Grammont PM. The Delta prosthesis [in French] Cahiers d’Enseignement SOFCOT. 1999;68:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergmann JH, Leeuw M, Jansen TW, Veeger DH, Willems WJ. Contribution of the reverse endoprosthesis to glenohumeral kinematics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:594–598. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billuart F, Devun L, Skalli W, Mitton D, Gagey O. Role of deltoid and passives elements in stabilization during abduction motion (0 degrees-40 degrees): an ex vivo study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30:563–568. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaimont P, Tahéri A, Vanderhostadt A. Displacement of the instantaneous center of rotation of the humeral head during abduction: implication for scapulohumeral muscular function [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(05)84356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 Suppl S):147S–161S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deries X. A Biomechanical Approach to Study the Effects of a Modification of the Rotation Center of a Shoulder Prosthesis on the Deltoid Strengths During the Abduction Movement [in French] [thesis]. Orsay, France: Université Paris XI; 1986.

- 13.Wilde LF, Audenaert EA, Berghs BM. Shoulder prostheses treating cuff tear arthropathy: a comparative biomechanical study. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:1222–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fick R. Anatomie und Mechunik der Gelenke. Teil III. Spezielle Gelenk- und Muskelmechanik. Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer LP, Carret JP, Gonon GP, Dimnet J. Cinematic study of the movements of the scapulohumeral joint [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1977;63(Suppl 2):108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FA., 3rd Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty: association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(88)80051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagey O, Hue E. Mechanics of the deltoid muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:250–257. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gérard Y, Leblanc JP, Rousseau B. A complete shoulder prosthesis [in French] Chirurgie. 1973;99:655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grammont PM. Place de l’ostéotomie de l’épine de l’omoplate avec translation, rotation, élévation de l’acromion dans les ruptures chroniques de la coiffe des rotateurs. Lyon Chir. 1979;55:327–329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics. 1993;16:65–68. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grammont PM, Bourgon J, Pelzer P. Study of a Mechanical Model for a Shoulder Total Prosthesis: Realization of a Prototype [in French]. Thèse de Sciences de l’Ingénieur. Dijon, France: Université Dijon; Lyon, France: ECAM de Lyon; 1981.

- 22.Grammont PM, Lelaurain G. Osteotomy of the scapula and the Acropole prosthesis (author’s transl) [in German] Orthopäde. 1981;10:219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grammont PM, Trouilloud P, Laffay JP, Deries X. Study and development of a new shoulder prosthesis [in French] Rhumatologie. 1987;39:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grammont PM, Trouilloud P, Sakka M. Translation-rotation osteotomy, 1975–1985: experiences with anterior impingement and incomplete lesions of the rotator cuff [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1988;74:337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1742–1747. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez S, Levy JC, Lee WE, 3rd, Keller TS, Maitland ME. Center of rotation affects abduction range of motion of reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;458:78–82. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31803d0f57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawkins RJ, Bell RH, Jallay B. Total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;242:188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolbel R, Friedebold G. Shoulder joint replacement [in German] Arch Orthop Unfallchir. 1973;76:31–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00416651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neer C, Craig E, Fukuda H. Cuff tear arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1232–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Gerber C. Biomechanical relevance of glenoid component positioning in the reverse Delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Simmen BR, Gerber C. Analysis of a retrieved Delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1187–1191. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B8.15228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:800–805. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.03042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearl R, Schultz F. Human Biology: A Record of Research. Baltimore, MD: Warwick and York Inc Publishers; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock RG, Deliz ED, Mcllveen SJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Prosthetic replacement in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:173–186. doi: 10.1016/1058-2746(92)90011-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Crosby LA, Mauldin M, Zuckerman JD. An evaluation of the relationships between reverse shoulder design parameters and range of motion, impingement, and stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Cofield R, Rowland C. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1814–1822. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torrens C, Lopez JM, Puente I, Caceres E. The influence of the acromial coverage index in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams GR, Jr, Rockwood CA., Jr Hemiarthroplasty in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:362–367. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(96)80067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuckerman JD, Scott AJ, Gallagher MA. Hemiarthroplasty for cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:169–172. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(00)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]