Abstract

Background

Reported early complication rates in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty have widely varied from 0% to 75% in part due to a lack of standard inclusion criteria. In addition, it is unclear whether revision arthroplasty is associated with a higher rate of complications than primary arthroplasty.

Questions/purpose

We therefore (1) determined the types and rates of early complications in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty using defined criteria, (2) characterized an early complication-based learning curve for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, and (3) determined whether revision arthroplasties result in a higher incidence of complications.

Patients and Methods

From October 2004 to May 2008, an initial series of 200 reverse total shoulder arthroplasties was performed in 191 patients by a single surgeon. Forty of the 200 arthroplasties were revision arthroplasties. Of these, 192 shoulders were available for minimum 6-month followup (mean, 19.4 months; range, 6–49.2 months). We determined local and systemic complications and distinguished major from minor complications.

Results

Nineteen shoulders involved local complications (9.9%), including seven major and 12 minor complications. Nine involved perioperative systemic complications (4.7%), including eight major complications and one minor complication. The local complication rate was higher in the first 40 shoulders (23.1%) versus the last 160 shoulders (6.5%). Seven of 40 (17.5%) revision arthroplasties involved local complications, including two major and five minor complications compared to 12 of 152 (7.9%) primary arthroplasties, including five major and seven minor complications. Nerve palsies occurred less frequently in primary arthroplasties (0.6%) compared to revisions (9.8%).

Conclusions

The early complication-based learning curve for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty is approximately 40 cases. There was a trend toward more complications in revision versus primary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty and more neuropathies in revisions.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the guidelines online for a complete description of level of evidence.

Introduction

Before the introduction of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA), surgical treatment of the painful, arthritic, rotator cuff-deficient shoulder was unpredictable. RTSA reduces shoulder pain and improves function by restoring active forward elevation. By medializing the shoulder’s center of rotation, recruitment of deltoid muscle fibers is increased, and the mechanical advantage of the shoulder-humerus complex improves, which allows the deltoid to compensate for the dysfunctional rotator cuff [1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 14–17].

Multiple studies reporting function and radiographic outcomes of RTSA have reported highly variable complication rates ranging from 0% to 75% [1, 2, 6, 8, 11, 15–18]. This large range suggests a lack of reproducibility of RTSA with various surgeons, centers, techniques, or devices, a lack of standardized criteria for complications, or both. The uncertainty in the complication risk may make some surgeons wary of performing this procedure. When deciding to perform RTSA, it is important to consider the underlying cause of the complication rate’s variability and the degree of severity of the high-rate complications. Of all the studies reporting complication rates of RTSA, only one has described a complication-based learning curve (10 procedures), and it only included 20 shoulders with 3-month minimum followup and no specified criteria for what events were considered complications [18]. Therefore, it is still not clear whether the RTSA learning curve has been accurately described. There has also been conflicting evidence as to whether revision arthroplasties are at higher risk for complication than primary arthroplasties. Werner et al. [17] found no difference in the overall complication rate between primary and revision arthroplasties in a series of 58 shoulders. However, Wall et al. [16] found a higher complication rate with revision RTSA versus primary RTSA in a series of 191 shoulders. Again, neither of these studies specified their criteria for what events were considered complications.

The purposes of our study were (1) to describe the types and frequency of complications in RTSA based on defined criteria, (2) to characterize an early complication-based learning curve for RTSA that reveals the types and severity of complications most affected by surgeon experience, and (3) to determine whether the rates of complications are higher in revision RTSA than in primary RTSA.

Patients and Methods

Since 2004, all patients undergoing RTSA by the senior author (JMW) have been offered participation in a prospective RTSA outcomes registry. Any patient medically capable of tolerating RTSA was offered this procedure after failed nonoperative treatment for a painful rotator cuff-deficient shoulder (anatomically and/or functionally deficient) or failed previous shoulder arthroplasty with rotator cuff deficiency and/or glenoid deficiency that was unreconstructible with an anatomic cemented polyethylene glenoid component. Patients were not offered RTSA unless they had functional and/or anatomic rotator cuff impairment in addition to any diagnosis amenable to arthroplasty treatment (Table 1). From October 2004 to May 2008, 209 RTSAs were performed in 200 patients. Nine patients (one shoulder each) refused to consent for participation. Of the remaining 191 patients (200 shoulders), seven (eight shoulders) had less than 6 months’ followup, leaving 184 patients (192 shoulders) for this study. Of the eight shoulders with less than 6 months’ followup, seven belonged to patients who stopped returning our followup calls after 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.7, 3.4, 5.0, and 5.9 months postoperatively. One belonged to a patient who died from a myocardial infarction on Postoperative Day 2. Of the 192 shoulders, 152 were primary RTSA and 40 were revision. The average age at time of the operation was 71 years (range, 48–92 years). The mean age of patients undergoing primary arthroplasty was 71.5 years, which was similar (p = 0.067) to the mean age of 68.5 years in patients undergoing revision arthroplasty. The mean age of the first 40 patients was 72.3 years, which was similar (p = 0.51) to the mean age of 70.5 years in the remaining patients. (See the rationale subsequently for comparing the first 40 shoulders to the remainder.) There was a comparable (p = 0.51) percentage of revision arthroplasties in the first 40 shoulders (25%) compared to the remaining 160 shoulders (18.8%). The minimum followup was 6 months (mean, 19.4 months; range, 6–49.2 months). No patients were recalled specifically for this study; all data were obtained from medical records and radiographs. This study was approved by our institution’s Human Investigation Committee.

Table 1.

Distribution of preoperative diagnoses

| Diagnosis (associated local complications, major, minor)* | Overall | First 40† | Last 160† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotator cuff tear arthropathy (7, 2, 5) | 77 | 20 | 57 |

| Irreparable rotator cuff tear (3, 2, 1) | 49 | 4 | 45 |

| Failed hemiarthroplasty or humeral head resurfacing (6, 2, 4) | 31 | 9 | 22 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (1, 0, 1) | 12 | 4 | 8 |

| Osteoarthritis with rotator cuff tear (0) | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Failed anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (1, 0, 1) | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| Humeral surgical neck nonunion (0) | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Chronic anterior dislocation (1, 1, 0) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Proximal humerus malunion (0) | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Failed reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (0) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Four-part proximal humerus fracture (0) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep infection after prior proximal humerus open reduction, internal fixation (0) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

* Overall complication rates were similar (p = 0.211, chi square test) among the various preoperative diagnoses; major and minor complications were not compared because of too few complications; †preoperative diagnosis distribution was similar (p = 0.261, chi square test) across the first 40 and last 160 shoulders.

The senior author performed all procedures. An attending anesthesiologist administered an interscalene regional block preoperatively, and supplementary intravenous sedation or general anesthesia was used intraoperatively as needed. A deltopectoral approach was performed in all cases with a superior-to-inferior tenotomy of the subscapularis tendon 1.5 cm medial to the bicipital groove, when present. In 150 of the shoulders, the superior third of the pectoralis major tendon was released to aid exposure. When present (132 of 192 shoulders), the long head of the biceps tendon was tagged with a traction suture and released and the intra-articular segment excised. The humeral head was osteotomized in 0° to 10° of retroversion. The glenohumeral capsule was released around the entire glenoid, and, when necessary, the inferior scapular neck origin of the long head of the triceps was released to aid glenoid exposure in tight shoulders. All patients received a Grammont-style RTSA prosthesis (Delta III®, DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, Warsaw, IN; Reverse Aequalis®, Tornier, Inc, Grenoble, France; Trabecular Metal™ Reverse Shoulder, Zimmer, Inc, Warsaw, IN) (Table 2). The senior author initially chose to use the DePuy prosthesis. Between Shoulders 16 and 25, he gradually transitioned to using the Tornier prosthesis because he preferred the variable angle screws in the Tornier baseplate. From Shoulder 73 to 160, he gradually transitioned to using the Zimmer prosthesis more often to decrease his use of cemented stems (Table 2). During closure, the subscapularis tendon (when present) was repaired to the tendon stump with Number 2 nonabsorbable sutures. One hundred thirty shoulders had normal, repairable subscapularis tendons; 15 shoulders had torn, repairable subscapularis tendons; and 47 shoulders had irreparable subscapularis tendon tears. Soft tissue tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon (when present) was performed by incorporating it into the pectoralis major tendon repair. Of the shoulders who had tenodeses, there were 113 with a normal tendon and 19 with a degenerated or partially torn tendon. The remaining 60 patients had absent or ruptured long head of the biceps tendons. Deep and superficial suction drains were used in all cases and maintained for a minimum of 48 hours.

Table 2.

Distribution of prostheses

| Prosthesis (associated local complications, major, minor)* | Overall | First 40 | Last 160 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DePuy Delta III (4, 0, 4) | 18 | 18 | 0 |

| Tornier Aequalis (7, 4, 3) | 69 | 21 | 48 |

| Zimmer Trabecular Metal (8, 3, 5) | 105 | 0 | 105 |

* Distribution of overall complications was similar (p = 0.159, chi square test) for the three prostheses; major and minor complications were not compared because of too few complications.

Postoperatively, patients remained in a shoulder immobilizer at 15° abduction for 4 weeks. Physical therapy for hand, wrist, and elbow ROM exercises was started on the first postoperative day, and progressive shoulder ROM was started after 2 weeks. Patients were asked to return for clinical and radiographic followup at 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter. All adverse events were reported to our institution’s Human Investigation Committee, and the authors considered these events for inclusion as complications based on the criteria described subsequently.

To improve the objectivity and reproducibility of our results and to best characterize the learning curve with useful types of complications, we defined criteria for events included as complications and types (Table 3). Complications were initially divided into two main groups: local complications and perioperative systemic complications. Local complications included all intraoperative and postoperative problems involving the operative extremity. Perioperative systemic complications included all other health-related adverse events initiated within 2 weeks of the operation. Next, we classified complications as either major or minor. Based on the work of Chin et al. [3], we defined local complications as major if the final result was compromised or reoperation was required. Minor complications included those that did not compromise outcome and little or no treatment was required. Reoperation was defined as any return to the operating room for the operative shoulder regardless of whether an open procedure took place. Systemic complications were classified as major and minor based on standard criteria for perioperative medical complications [4]. Patients earlier in the series had longer followup than those later in the series; therefore, to eliminate followup as a confounding factor, we only included complications occurring during the first 6 months postoperatively.

Table 3.

Adverse event inclusion/exclusion criteria for complications

| Complication type | Inclusion criteria for events (one or more criteria needed) | Exclusion criteria for events |

|---|---|---|

| Local complications (intraoperative) | Altering the procedural routine | Deviating from standard surgical protocol due to an intentional act that was necessary for prosthesis removal and reconstruction during revision arthroplasty |

| Altering the final implanted prosthesis or instrumentation | ||

| Deviating from routine postoperative protocol | ||

| Local complications (postoperative) | Resulting in reoperation | Altering function due to pain without a mechanical etiology |

| Deviating from rehabilitation protocol due to prescribed activity limitation | ||

| Altering the operative extremity function from the expected course | ||

| Scapular notching resulting in shoulder dysfunction or baseplate loosening | ||

| Perioperative systemic complications | Resulting in nonstandard treatment (not diagnostic tests) | Transfusion for blood loss anemia (considered a normal variation) |

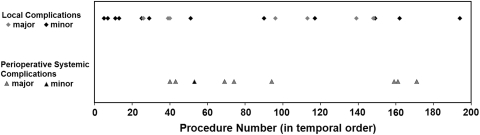

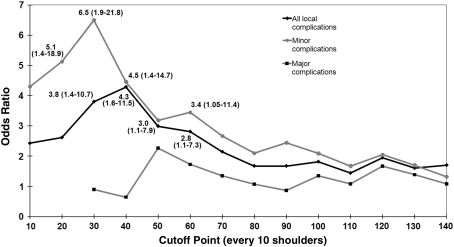

We defined the learning curve as the point in the series where there was the lowest risk of local complication in subsequent shoulders compared to earlier shoulders (based on odds ratio). To determine the relevant number of procedures and avoid choosing an arbitrary number (eg, the first 100 versus the second 100), we graphed the distribution of local and perioperative systemic complications over the course of the first 200 procedures (Fig. 1). We did not perform further analysis of the perioperative systemic complications because there was no discernible pattern. Since the graph showed a tighter clustering of local complications before 40 procedures, we chose to use the first 40 shoulders (39 with minimum 6-month followup) versus the last 160 (153 with minimum 6-month followup) for our initial local complication analysis. Analyses of the local complication learning curve were also performed using cutoff points of the first 140 shoulders in increments of 10 to better characterize the learning curve throughout the series and further validate our chosen point of 40 procedures. These analyses were not continued past 140 shoulders for three reasons: (1) after this point, the analysis becomes less meaningful because of too few shoulders in the later group; (2) by this point in the series, a trend was already evident; and (3) prior studies examining learning curves suggest the learning curve would likely be reached long before 140 procedures [10, 13, 18].

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the distribution of complications (local and perioperative systemic complications) over the initial 200 operations. The graph shows a tighter clustering of local complications before 40 procedures, whereas the perioperative systemic complications were evenly distributed throughout the series.

Complication rates and types in primary arthroplasties were compared to those in revision arthroplasties. All the analyses listed were repeated using the major and minor complication subgroups.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare complication rates between groups. The chi square test was used to analyze prosthesis distribution over earlier and later groups and prosthesis as a risk factor for complication. Odds ratios were also calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For age comparisons, data distributions in each group were analyzed for normality. These data were determined to have a nonnormal distribution, and so the Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot® 11 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA).

Results

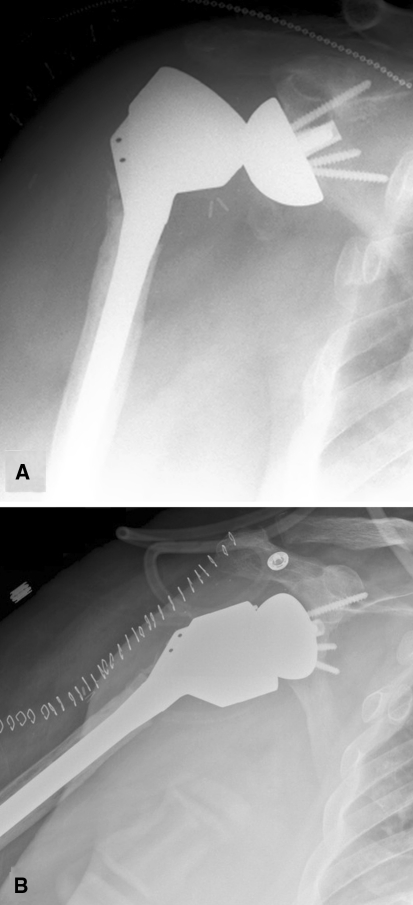

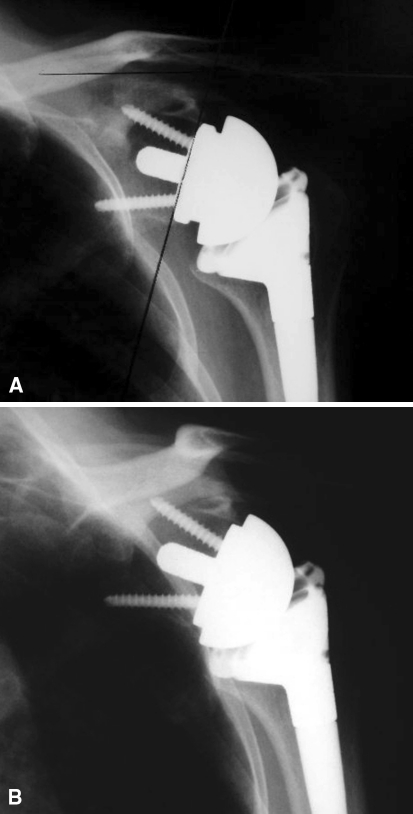

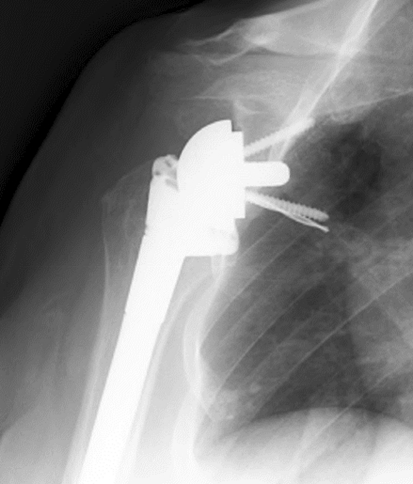

The most common types of complications were transient neuropathy (five), intraoperative fracture (four), and postoperative dislocation (three) (Fig. 2), with less common types including an incompletely seated glenosphere (one) (Fig. 3), intraoperatively broken screw head (one) and drill bit (one) (Fig. 4), chronic subluxation (two), acromion fatigue fracture (one), and painful cerclage wires (one) (Table 4). Nineteen shoulders involved local complications (9.9%), including seven major and 12 minor complications (Table 5). Nine involved perioperative systemic complications (4.7%), including eight major complications and one minor complication. There were no complications related to scapular notching, which occurred in 49 shoulders (25.5%) by 6 months postoperatively. No shoulders required revision of the humeral or glenosphere components.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) An AP radiograph shows an unstable long-stem revision arthroplasty dislocated postoperatively. (B) A radiograph shows the rerevised prosthesis with two stacked 9-mm metallic spacers.

Fig. 3A–B .

(A) An AP radiograph shows an incompletely seated glenosphere at 2 weeks postoperatively. Examination under anesthesia revealed the prosthesis to be stable. (B) A radiograph shows the glenosphere spontaneously seated 2 weeks later.

Fig. 4.

An AP radiograph shows a drill bit left in situ after breaking during drilling for the inferior baseplate screw. A new pathway was drilled for the screw.

Table 4.

Summary of complications

| Complication | Number | Reoperation | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transient neuropathy (all minor) | 5 | 0 | Complete recovery within several weeks |

| Intraoperative fracture (all minor) | 4 | 0 | 2 anterior-inferior glenoid fractures left in situ and healed |

| 1 greater tuberosity fracture internally fixed | |||

| 1 humeral shaft fracture treated with fracture brace | |||

| Postoperative dislocation* (all major) | 3 | 3 | 1 closed reduction |

| 1 open reduction | |||

| 1 open reduction with placement of 2 stacked 9-mm spacers (Fig. 2)† | |||

| Incompletely seated glenosphere (major) | 1 | 1 | Examination under anesthesia revealed a stable prosthesis; glenosphere spontaneously seated (Fig. 3) |

| Intraoperative broken screw head (minor) | 1 | 0 | Broken screw left in situ and new screw placed |

| Broken drill bit within the scapula (minor) | 1 | 0 | Drill bit left in situ (Fig. 4) |

| Chronic subluxation (major) | 2 | 0 | Tolerable with activity modification |

| Acromion fatigue fracture (minor) | 1 | 0 | Healed |

| Painful cerclage cables (major) | 1 | 1 | Pain resolved after cables removed |

* All three dislocations occurred within the 47 shoulders with irreparable subscapularis tendons; †one of three dislocations occurred in revision arthroplasty.

Table 5.

Local complications in the first 40 versus the last 160 shoulders

| Type of complication | Overall (192 analyzed) | First 40 (39 analyzed) | Last 160 (153 analyzed) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All local complications | 9.9% | 23.1% | 6.5% | 4.3 (1.6–11.5) | 0.005 |

| Major local complications | 3.6% | 7.7% | 2.6% | 3.1 (0.67–14.5) | 0.150 |

| Minor local complications | 6.3% | 15.4% | 3.9% | 4.5 (1.4–14.7) | 0.017 |

* Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test; CI = confidence interval.

There was a higher (p = 0.005) overall local complication rate in the first 40 shoulders than in the last 160 (Table 5). This result was most influenced by minor complications, which were greater (p = 0.017) in the earlier group than in the later group, while major complications were only slightly more common (p = 0.150) in the earlier group than in the later group (Table 5). Repeating this analysis at other cutoff points (every 10 procedures) revealed higher overall local complication rates in earlier shoulders than in later shoulders from Procedures 30 through 60 with the greatest difference at 40 procedures (Fig. 5). Subanalysis of the minor complications also revealed higher complication rates from Procedures 20 to 40 and 60 with the greatest difference at 30 procedures (Fig. 5). Subanalysis of the major complications showed no differences in earlier versus later complication rates (Fig. 5). The overall perioperative systemic complications demonstrated no learning curve, with a rate of 4.7% including one minor and eight major complications evenly distributed throughout the series (Fig. 1).

Fig. 5.

This graph shows odds ratios (with 95% CIs) of complication rates in earlier shoulders to later shoulders in the series for cutoff points at every 10 shoulders. Significant values with 95% CIs are included. The complication rates were different only from Points 30 to 60, and the odds ratio peaked at 40 procedures for overall complications and 30 procedures for minor complications. CIs = confidence intervals.

The local complication rate was similar (p = 0.08) in patients undergoing primary RTSA and those having revision RTSA (Table 6). The incidence of postoperative neuropathies was higher (p = 0.007) in revision RTSA compared to primary RTSA.

Table 6.

Complications in primary versus revision reverse shoulder arthroplasties

| Type of complication | Primary arthroplasty (152 analyzed) | Revision arthroplasty (40 analyzed) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All local complications | 7.9% | 17.5% | 2.5 (0.9–6.8) | 0.080 |

| Major local complications | 3.3% | 5.0% | 1.5 (0.3–8.3) | 0.637 |

| Minor local complications | 4.6% | 12.5% | 3.0 (0.9–9.9) | 0.133 |

| Transient neuropathies | 0.7% | 10.0% | 16.8 (1.8–154.7) | 0.007 |

| Perioperative systemic complications | 5.9% | 5.0% | 0.84 (0.2–4.0) | 1.00 |

* Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Reported early complication rates in RTSA have widely varied likely due to a number of factors, one of which is a lack of standard inclusion criteria. For counseling patients and perhaps selecting patients, it is important to know the complication rates. In addition, it is unclear whether revision arthroplasty is associated with a higher rate of complications than primary arthroplasty. We therefore (1) described the types and rates of early complications in RTSA, (2) characterized a learning curve for our RTSA series to establish where the greatest reductions in complication rates occurred, and (3) determined whether revision RTSA results in more complications or certain types of complications than primary RTSA.

When interpreting our findings, readers should be aware of certain limitations. First, we would have ideally included a uniform population with no revision arthroplasties and only one prosthesis manufacturer. However, determining the learning curve required that we use a consecutive series of patients by a single surgeon. Therefore, we did not exclude revision arthroplasties or certain prosthesis brands because these cases provided the surgeon with experience that affected the learning curve. The similar proportion of revision arthroplasties earlier in the series compared to later likely minimized the effects of these cases. A standardized technique of exposure and prosthesis placement and similar biomechanics of the prostheses likely minimized limitation of having different models. The prostheses used in this study were all similar to the original Grammont-style design introduced more than 20 years ago: a neck-shaft angle more horizontal than anatomic, a large glenosphere with a short neck, and a medialized center of rotation. Our analysis also showed prosthesis type was not an independent risk factor for complication. Second, it may be difficult to accurately extrapolate our results to surgeons with varying levels of experience. Previous studies show increases in complication rates and length of hospital stay for shoulder arthroplasties performed by surgeons with less experience and in hospitals with lower volumes [9, 12]. All our procedures were performed by a fellowship-trained shoulder surgeon in a high-volume shoulder arthroplasty practice (> 225 procedures per year) who had considerable experience with anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty before performing RTSA. Therefore, higher complication rates may be seen in surgeons lacking sufficient experience with shoulder arthroplasty techniques, particularly glenoid exposure. This limitation does not invalidate our conclusions because surgeons with a similar shoulder practice can expect similar results, and surgeons with less shoulder arthroplasty experience can adjust their expectations based on their comfort level. Third, the 6-month minimum followup is also a limitation of the study. We believe this followup was acceptable since the scope of this study was to look at early complications of RTSA, rather than long-term complications. Only four of the 19 local complications occurred after 2 weeks postoperatively, suggesting most early complications happen much earlier than 6 months postoperatively; therefore, a longer minimum followup would likely not change our results much.

Our overall local complication rate in this series was 9.9%, which is lower than the rates reported for most RTSA outcomes studies (Table 7). None of the studies we found subdivided their complications with major and minor criteria. There are multiple factors likely contributing to the variability in reported complication rates, including preoperative diagnoses, lengths of followup, surgical techniques, and the variable sizes of study populations [5, 16]. Possibly the most important factor is the lack of standardized criteria for what events constitute complications. For example, Werner et al. [17] included 12 hematomas described as having no effect on final outcomes in their total of 33 shoulders with complications. Wierks et al. [18] reported a 75% complication rate including stitch abscesses and the need for redrilling the center glenoid hole. Such a low threshold for events to be counted as complications artificially increases complication rates, compared to other series that likely observed such events but did not include them as complications. Using our well-defined inclusion criteria for complications, we found a 9.9% local complication rate with 3.6% major and 6.3% minor. Perhaps using similar criteria would have produced comparable complications rates at 6 months’ followup in the cited series.

Table 7.

Comparison of reported complication rates in reverse shoulder arthroplasty studies

| Study | Population size | Minimum followup | Complication rate | Percent revisions | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rittmeister and Kerschbaumer [14] | 6 | 4 years | 50% | 0 | All rheumatoid arthritis |

| Werner et al. [17] | 58 | 2 years | 50% | 0 | |

| Frankle et al. [6] | 60 | 2 years | 17% | 0 | |

| Wall et al. [16] | 191 | 2 years | 19% | 28% | |

| Guery et al. [8] | 60 | 5 years | 15% | 0 | |

| Wierks et al. [18] | 20 | 3 months | 75% | 20% | An initial consecutive series |

To our knowledge, this is the largest study focusing on early complications and the learning curve of RTSA. Wierks et al. [18] presented a series of 20 RTSAs with minimum 3-month followup and found an intraoperative complication-based learning curve of 10 shoulders. Using a cutoff point of 10 shoulders for their data analysis was based on “most procedures.” To further substantiate our 40 procedures for the learning curve analysis, we reviewed other large-volume studies of learning curves, including a series of 100 initial computer navigation-assisted hip resurfacing arthroplasties with a learning curve of 60 procedures [13] and a series of 100 minimally invasive TKAs with a learning curve of 50 procedures [10].

Reported complication rates in revision RTSA have ranged from 30% to 50%, and these rates are inconsistently higher than those in primary RTSA [7, 16, 17]. The most common complication specifically associated with revision RTSA is often dislocation [7]. In our series, the complication rate in revision RTSA was 17.5%, with a 2.5% dislocation rate and a 2.5 (95% CI, 0.9–6.8) times higher risk for complication than that in primary RTSA. It is unclear why our complication rate with revisions was lower than others’ reported rates although severity of preoperative pathology might be a major contributor.

In summary, our overall complication rate was similar to those previously reported in large RTSA outcomes studies. The major differences in our study were the detailed criteria of what events were deemed complications and the large population with a high followup rate, which allowed us to characterize a learning curve for RTSA. The learning curve was most substantial at 40 cases and was most influenced by minor complications. Complication risk in revision RTSA can be highly variable depending on the severity of preoperative pathology.

Acknowledgment

An internal grant from the William Beaumont Hospital Research Institute was used to maintain a reverse shoulder arthroplasty patient registry. One author (JMW) certifies that he has or may receive payments or benefits as a consultant from a commercial entity (Zimmer, Inc, Warsaw, IN) related to this work.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at William Beaumont Hospital.

References

- 1.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 Suppl S):147S–161S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulahia A, Edwards TB, Walch G, Baratta RV. Early results of a reverse design prosthesis in the treatment of arthritis of the shoulder in elderly patients with a large rotator cuff tear. Orthopedics. 2002;25:129–133. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20020201-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin PY, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Schleck C. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty: are they fewer or different? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1259–1265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards TB, Williams M, Labriola J, Elkousy H, Gartsman G, O’Connor D. Subscapularis insufficiency and the risk of shoulder dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:892–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency: a minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1697–1705. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Nyffeler RW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:284–295. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1742–1747. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond J, Queale W, Kim T, McFarland E. Surgeon experience and clinical and economic outcomes for shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2318–2324. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King J, Stamper DL, Schaad DC, Leopold SS. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty compared with traditional total knee arthroplasty: assessment of the learning curve and the postoperative recuperative period. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy J, Frankle M, Mighell M, Pupello D. The use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:292–300. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nitin J, Peitrobon R, Hocker S, Guller U, Shankar A, Higgins L. The relationship between surgeon and hospital volume and outcomes for shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:496–505. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen M, Davis ET, Waddell JP, Schemitsch EH. Imageless computer navigation for placement of the femoral component in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:310–315. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:17–22. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.110515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Mole D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff: results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall B, Nove-Josserand L, O’Connor D, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1476–1485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1476–1486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wierks C, Skolasky R, Ji J, McFarland E. Reverse total shoulder replacement: intraoperative and early postoperative complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]