Abstract

We report a case of primary transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of a bladder diverticum along with a literature review. A 55-year-old male presented with painless gross hematuria. A histological diagnosis of TCC within a bladder diverticulum was made following cystoscopical examination. Initially transurethral resection of bladder tumour with subsequent intravesical chemotherapy followed. As a result of recurrence and in view of bladder-sparing therapy, a distal partial cystectomy was performed. This report demonstrates that conservative bladder-sparing treatment can be achieved and subsequently followed by vigilant cystoscopy.

Introduction

Transitional cell carcinomas (TCC) of a bladder diverticulum are rare and behave like bladder TCC elsewhere.1–3 They are the most common primary neoplasm in the bladder diverticulae and are more prevalent in men. The incidence of TCC varies from 0.8% to 13%.4 Due to the lack a muscular layer, stasis within the diverticulum increases the risk of development urological disease, including malignancy. Other risks are those associated with development of TCC elsewhere in the bladder. We report a TCC in a bladder diverticulum.

Case report

A 55-year-old-male presented to the urology service of a university hospital with a history of painless gross hematuria. He had 3 episodes of hematuria over a 12-month period prior to his presentation. No pain, lower urinary tract symptoms or systemic symptoms were associated. A digital rectal examination of the prostate was unremarkable. Comorbidity factors included morbid obesity and hypertension. The patient had no known risk factors for TCC. Full hematological and biochemical studies were within normal ranges. Serum creatinine was 79 mmol/L (range: 60–120 mmol/L) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was 0.9 ng/dL (range: 0–4 ng/dL).

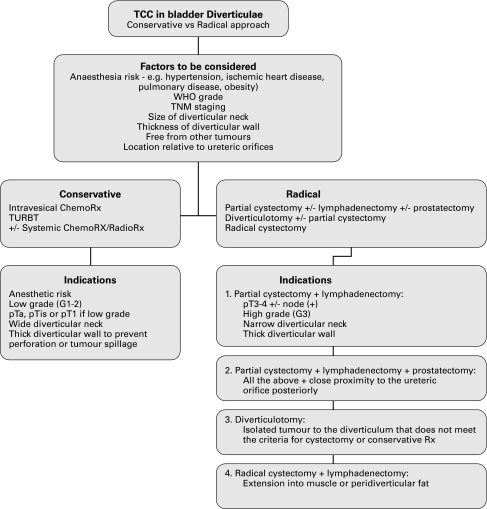

Computed tomography (CT) showed a fluid filled structure on the right posterior wall of the bladder consistent with a bladder diverticulum. A bladder mucosal lesion consistent with TCC of the bladder was also identified within the bladder diverticulum. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was subsequently performed to further characterize the anatomy of the lesion; it confirmed the finding of bladder tumour within bladder diverticulum arising from the right posterior wall of the bladder (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1a.

Magnatic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showing bladder tumour within bladder diverticulum: MRI sagittal section.

Fig. 1b.

Magnatic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showing bladder tumour within bladder diverticulum: MRI coronal section.

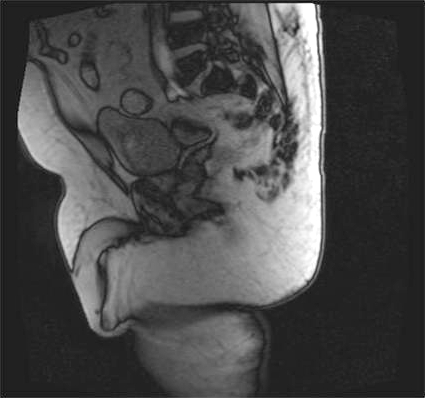

Subsequent cystoscopy showed a large papillary bladder tumour within a single large bladder diverticulum. The diverticulum was located distally and posteriorly within the bladder, just above and lateral to the right ureteric orifice. It measured about 4 × 4 × 3 cm. The bladder tumour was located circumferentially within the bladder diverticulum. At this point, it was partially resected via transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) and chippings were taken for histological diagnosis (Fig. 2). The rest of the bladder was grossly normal and free of tumour spread. Histology showed papillary TCC, grade 1, stage pTa.

Fig. 2.

Part A: Cystoscopy showing papillary tumour in bladder diverticulum during transurethral resection of a bladder tumour. Part B: Repeat cystoscopy (5 months post diagnosis) shows recurrence of a papillary tumour in right wall of bladder diverticulum.

Six cycles of intravesical epirubicin (80 mg) were administered and CT staging showed no extravesical extension or distant metastasis.

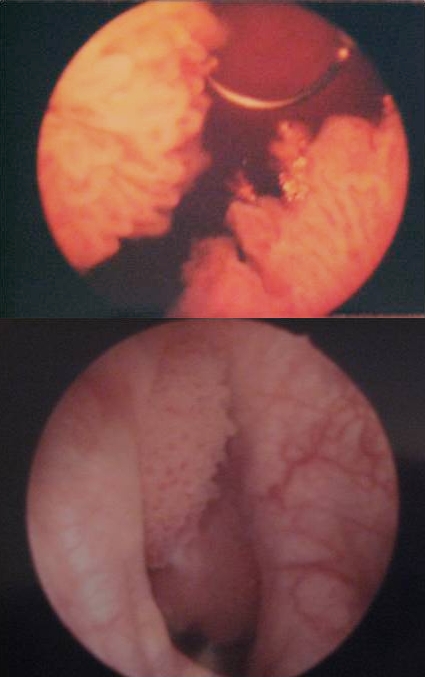

Repeat cystoscopy at 5 and 9 months following the initial diagnosis showed recurrence within the diverticulum. Subsequently, in both instances, the tumour was partially resected with histology showing pT1G2 (Fig. 3a, Fig. 3b, Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

a. Histology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. A high-power (20 × objectives) view of of well-differentiated transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain). Fig. 3b. Histology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. A high-power (40 × objectives) of a focus of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain). Fig. 3c. Histology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Bladder tissue, invaded by well-differentiated transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (4 × objective) (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain).

In view of the location of diverticulum and its difficult access, this case was discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting. The team recommended a distal partial cystectomy and prostatectomy. Retropubic dissection was carried out and the endo-pelvic fascia was entered. The prostate and posterior wall of the bladder was dissected after dividing the urethra proximally. The bladder was then incised anteriorly and its distal portion resected circumferentially, with inclusion of ureteric orifices and diverticulum. Reconstruction of the bladder neck was then performed with a subsequent cystourethrostomy. Re-implantation of both ureters was performed using the Lich technique.

The postoperative period was uneventful and histological diagnosis showed small foci of residual papillary TCC, pTaG2. The margins were clear of disease. To date, follow-up cystoscopies have been free of tumour recurrence.

Discussion

Bladder diverticulae can be defined as herniations of the bladder mucosa through areas of weakness within the detrusor muscle. As they are only lined by a mucosal layer, both therapeutic and prognostic difficulties are encountered. They can be classified into congenital and acquired. The latter occurs as a result of increased intravesical pressure secondary to bladder outflow obstruction. These are common, usually multiple and are associated with a trabecular bladder. Unlike acquired diverticulae, congenital diverticulae are a result of disarray of the muscle fibres within the musculature of the bladder wall. They are rare, usually solitary and associated with vesico-ureteric reflux and hydronephrosis.1,2 In addition, bladder diverticulae can usually occur in close proximity to the ureteric orifices.1

The incidence of bladder diverticula is about 1.7% and the incidence of TCC within these diverticula range from 0.8% to 13%.1–4 As with bladder TCC elsewhere, the main presentation is painless hematuria. The risk factors for the development of TCC of a bladder diverticulum are those of ordinary bladder tumours, as well as those that increase the risk of developing these acquired diverticula.4 As bladder diverticula lack a muscle layer and have inadequate emptying of the diverticulae, the risk of urinary tract pathologies, including urinary tract infection (UTI) and malignancies, increases.1–5

Transitional cell carcinomas are staged, according to the tumour, nodes and metastasis (TNM staging system), into superficial (Tis/Ta), superficially invasive (T1), extradiverticular (T3) and extravesical (T4). In 1973, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified bladder tumours based on the degree of cellular differentiation, as either urothelial papilloma, low-grade (G1 and G2) and high-grade (G3) which denotes the grade of the tumour, ranging from well-differentiated (G1) to moderately differentiated (G2) and finally poorly differentiated (G3). Moreover, they are also classified based on their growth pattern: papillary (70%), sessile (20%) and nodular (10%). Lastly, the WHO recognizes Tis, which is a sessile, non-invasive, high-grade tumour. However, in 2004 in conjunction with the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP), a new grading system was developed which included both architectural and histological criteria; therefore, the grades changed to: urothelial papilloma, papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential, low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma and high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma.5,6 The use of the 2004 WHO/ISUP grading system, in theory, should increase inter-observer reproducibilty of diagnosing bladder tumours that are better stratified according to risk of recurrence and progression of non-muscle invasive tumours, low-grade and high grade bladder carcinomas compared to the WHO 1973 criteria. However, studies have shown that the 2004 WHO/ISUP is not fully validated and the reproducibilty in the non-muscle invasive group is not increased. Thus, the 1973 WHO grading system is still the gold standard until the 2004 WHO/ISUP is fully validated.7–11

Epidemiological studies have shown that 75% to 80% of bladder tumours present as non-muscle invasive, 70% of which are Ta lesions, 20% T1 lesions and 10% is Tis. The remaining 20% to 25% present as muscle invasive.12–14

The clinical course of bladder tumours have a wide range of outcomes, ranging from non-muscle invasive tumours which are low-grade superficial tumours, with minimal risk of death, to, muscle-invasive tumours which are high-grade invasive tumours which are often fatal. This can be explained by the pathophysiology and oncological properties of bladder tumours. They are often described as a tumour with an implantation problem resulting in migration of the tumour to other sites, thus creating a multifocal field defect. Oncological properties also vary between different grades. Low-grade tumours have a relatively low recurrence rate and a low risk of progression; whereas, high-grade tumours have an increased propensity for malignant change and recurrence. Prognosis and long-term outcome are best predicted by the initial histological grade at the time of diagnosis, depth of invasion and the presence of Tis.15

Heterogeneity in the behaviour of non-muscle invasive bladder tumours has made it very difficult to create uniformly accepted algorithms for the treatment of TCCs. Therefore, many educational bodies, including the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, have stressed the importance of risk stratifying patients by risk of recurrence and progression; this creates a risk profile to determine the best management plan for each group based on evidence. It must be noted that the limitiations of using the EORTC risk calculator is that the risk groups are based on patients who were treated with older intravesical chemotherapy regimens and, therefore, may not be predictive of results with newer chemotherapy regimens or with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy and multiple TURBTs. Moreover, very few cases of Tis were used in the development of the risk calculator, therefore accurately estimating the risk of recurrence and progression in these patients may not be precise.15

As with the heterogeneity of non-muscle invasive bladder tumours, diverticular TCCs have diagnostic and management complexities, as well as therapeutic difficulties. The gold standard of treatment for a TCC of a bladder diverticulum is radical cystectomy. Other approaches include more conservative measures, including partial cystectomy, laparoscopic diverticulectomy and TURBT, all with or without consequent intravesical chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.16–18

The diverticula and its neck can significantly vary in size. The presence of a narrow diverticular neck as well as its location in relation to the urinary bladder wall provides technical difficulties and makes TURBT very difficult. Moreover, the lack of a muscle layer makes complete resection of the tumour via the transurethral approach very difficult and complicated due to concerns associated with perforation and tumour spillage.16–19 Moreover, the lack of a muscle layer makes it difficult to predict long-term survival because the tumours cannot be grouped into superficial versus invasive.16

Because of the diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties explained above, as well as the high tendency of bladder tumours to recur, Garzotto and colleagues demonstrated that bladder tumours, confined to diverticulae that are treated conservatively, should be treated with a multimodal approach rather than a solitary surgical approach regardless of the tumour stage.19 The authors found an 89% 4-year disease-free period while avoiding a cystectomy.

The decision between the conservative and radical approaches in the treatment of tumours confined to bladder diverticulae is multivariable. Provided that all patients are suitable for a radical cystectomy and keeping with the assumptions of many factions worldwide, if the invasion of bladder tumour beyond the submucosa into the muscle is due to histological grade, then low-grade tumours (staged up to pT1) can be treated conservatively, regardless of the fact that bladder diverticulae lack the muscle layer. However, high-grade diverticulae tumours must be assumed to have higher tendency to invade the peridiverticular fat, as high-grade tumours elsewhere in the bladder would have more of a tendency to invade the muscle layer and is associated with a worst outcome. Moreover, the lack of a confining muscle layer means that diverticular neoplasms can theoretically spread faster or earlier than bladder tumours elsewhere and, therefore, special considerations must be taken.20

Golijanin and colleagues published 39 cases, the largest series on diverticular neoplasms, and found that the most important factor in outcome is clinical stage regardless of the histological grade.14 Ta/Tis can be treated with conservative measures, whereas T3 warrants a more radical approach. Golijanin and colleagues also showed that T1 tumours can be treated with conservative measures and regular follow-ups without compromising long-term outcome.14

Conclusion

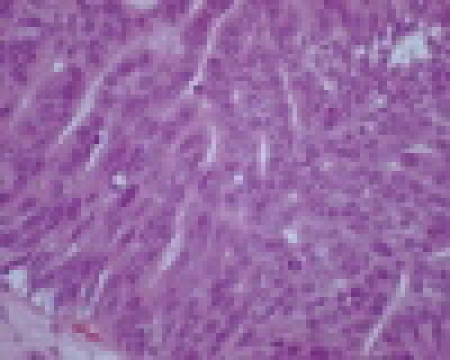

Given the rare nature of such tumours, there is a lack of systematic clinical studies detailing management algorithms in such cases. Therefore, little has been published on the surgical management of such entity. Based on our case study and following a literature review on the behaviour of bladder tumours regardless of their location, our case is consistent with many published series. We believe that the bladder-sparing approach with frequent follow-ups can be employed where possible. In our case, the initial histology and staging showed pTaG2; therefore conservative measures, with intra-vesical chemotherapy and TURBT followed by screening cystoscopies, were employed. However, when screening cystoscopies revealed recurrence with a higher grade and stage (pT1G2) and given the difficulties presented by the position of the diverticulum (preventing effective TURBT), a more radical approach was employed with a partial distal cystectomy. Repeat cystoscopies showed no recurrence to date; no urodynamic abnormalities or dysfucntional voiding occurred. We have also suggested a management algorithm that can be applied for patients with similar presentations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Algorithm for management of patient with transitional cell carcinoma in bladder diverticulum. TCC: transitional cell carcinoma; WHO: World Health Organization; Rx: therapy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Pieretti RV, Pieretti-Vanmarcke RV. Congenital bladder diverticula in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:468–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blane CE, Serin JM, Bloom DA. Bladder diverticula in children. Radiology. 1994;190:695–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.3.8115613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banial J, Vishna T. Primary transitional cell carcinoma in vesical diverticula. Urology. 1997;50:697–9. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haecker A, Riedasch G, Langbein S, et al. Diverticular carcinoma of the urinary bladder: diagnosis and treatment Problems. A case report. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14:121–4. doi: 10.1159/000083925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, et al. Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1435–48. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein Jl, Eble JN, Sesterhenn I, Sauter G., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumors, pathology and genetics of tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R. Non-invasive urothelial neoplasms: according to the most recent WHO classification. Eur Urol. 2004;46:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al. European Association of Urology (EAU) EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2008;54:303–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy WM, Takezawa K, Maruniak NA. Interobserver discrepancy using the 1998 World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology classification of urothelial neoplasms: practical choices for patient care. J Urol. 2002;168:968–72. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yorukoglu K, Tuna B, Dikicioglu E, et al. Reproducibility of the 1998 World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathology classification of papillary urothelial neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:734–40. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0905-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonul II, Poyraz A, Unsal C, Acar C, Alkibay T. Comparison of 1998 WHO/ISUP and 1973 WHO classifications for interobserver variability in grading of papillary urothelial neoplasms of the bladder. Pathological evaluation of 258 cases. Urol Int. 2007;78:338–44. doi: 10.1159/000100839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . World cancer report 2003. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2003. p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkali Z, Chan T, Manoharan M, et al. Bladder cancer: epidemiology, staging and grading, and diagnosis. Urology. 2005;66:4–34. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golijanin D, Yossepowitch O, Beck SD, et al. Carcinoma in a bladder diverticulum: Presentation an treatment outcome. J Urol. 2003;170:1761–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091800.15071.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49:466–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matta EJ, Kenney AJ, Barre GM, et al. Intradiverticular bladder carcinoma. Radiographics. 2005;25:1397–403. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Given RW, Parsons JT, McCarley D, et al. Bladder-sparing multimodality treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a five-year follow-up. Urology. 1995;46:499–504. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostroff EB, Alperstein JB, Young JD. Neoplasm in vesical diverticula: Report of 4 patients, including a 21-year-old. J Urol. 1973;110:65–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garzotto MG, Tewari A, Wajsman Z. Multimodal therapy for neoplasms arising from a vesical diverticulum. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62:46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199605)62:1<46::AID-JSO10>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aizawa T, Mamiya Y, Tochimoto M, et al. Three cases of transitional cell carcinoma in bladder diverticulum treated by a bladder-preserving approach. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1999;45:111–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]