Abstract

Background

The laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is derived from the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch operation (Marceau et al., Obes Surg 3:29–35, 1993; Hess and Hess, Obes Surg 8:267–82, 1998; Chu et al., Surg Endosc 16:S069, 2002). Later, LSG was advocated as the first step of a two-stage procedure for super-obese patients (Regan et al., Obes Surg 13:861–4, 2003; Cottam et al., Surg Endosc 20:859–63, 2006). However, recent support is mounting that continues to establish LSG as the definitive procedure for surgical treatment of morbid obesity. We will report our experience with the LSG as a primary bariatric procedure and evaluate if this operation is suitable as a stand-alone procedure.

Methods

The study is a nonrandomized retrospective analysis of 204 patients from a single surgeon operated between July 2006 and April 2010. The study comprises of 155 women and 49 men with a mean age of 45 years (range, 19–70 years), a mean preoperative weight of 126.6 kg, and body mass index (BMI) of 45.7 kg/m2.

Results

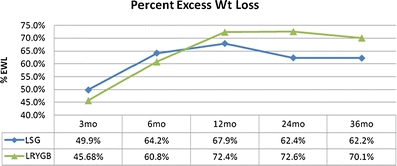

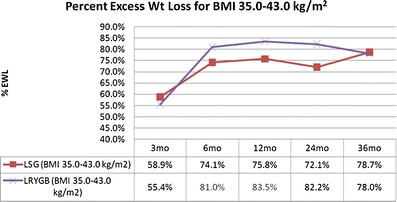

The mean percent excess weight loss (%EWL) was 49.9% (n = 159), 64.2% (n = 138), 67.9% (n = 77), 62.4% (n = 34), and 62.2% (n = 9) at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. For patients with BMI ≤43.0, the mean postoperative %EWL was 58.9% (n = 72), 74.1% (n = 67), 75.8% (n = 39), 72.1% (n = 17), and 78.7% (n = 5) at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. Operative complications include leak (0.0%), abscess (0.5%), hemorrhage (1.0%), sleeve stricture (1.0%), and severe gastroesphogeal reflux disease with need to convert to laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (0.5%).

Conclusions

LSG yields excellent outcomes with low complication rates for morbidly obese patients. We advocate LSG as a safe and effective stand-alone procedure, especially with the lower BMI population (BMI 35.0–43.0 kg/m2).

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, Morbid obesity, Sleeve gastrectomy, Gastric bypass, Lower BMI population

Introduction

The laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is derived from the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch operation (BPD-DS) [1–3]. Sleeve gastrectomy functioned as the restrictive component of the procedure. Later, LSG was advocated as the first step of a two-staged procedure for high-risk patients, with the intention of reducing co-morbidities and operative risk, and to be followed by either BPD-DS or laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) [4, 5]. However, often, satisfactory weight loss was achieved after LSG, and second-stage procedures were found to be unnecessary [6, 7]. Because of the success of LSG in the first stage, it is gaining momentum as an isolated bariatric procedure [8–10].

The success of the sleeve can be attributed to two main factors. First, a high-pressure system is conceived from a narrow lumen with the pylorus intact, which results in optimal restriction and improved satiety [11]. Essentially, LSG is a derivative of the Magenstrasse and Mill operation, with a completion of the Magenstrasse distally [12, 13]. Second, appetite suppression is achieved by removing the gastric fundus, the ghrelin-producing portion of the stomach. Numerous studies indicate that sharp declines in fasting and postprandial levels of this orexigenic hormone following LSG cause a long-term reduction of hunger feeling, which significantly reduces intake [14–18].

The aim of this retrospective, nonrandomized study is to report our experience with LSG as a primary bariatric procedure and determine if this operation is suitable for the lower body mass index (BMI) population (35.0–43.0 kg/m2).

Materials and Methods

Between July 2006 and April 2010, 204 patients underwent LSG performed by a single surgeon. The study group consisted of 155 women and 49 men with a mean age of 45 years (range, 19–70 years), a mean preoperative weight of 126.6 kg, and mean BMI of 45.7 kg/m2. The mean OR time was 92 ± 32 min, and mean length of stay was 2.3 days. A nonrandomized retrospective analysis was done.

Surgical Technique

The operation was performed under general anesthesia. A Verres needle is inserted in the left upper quadrant with insufflations of the abdominal cavity to a pressure of 15 mmHg. Six laparoscopic ports are inserted, three 5-mm and three 12-mm Endopath® Xcel™ Bladeless trocars (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.). The short gastric vessels are taken down along the greater curvature of the stomach with a Harmonic® scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.) approximately 3 cm from the pylorus, extending cephalad, taking the adhesions down around the fundus of the stomach. Once freed, a 34-Fr Edlich tube is inserted by anesthesia. This is guided to hug the lesser curvature. Once the Edlich tube is placed, sequential firings of the Echelon® 60™ Endopath stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.) with the green cartridge, as well as the Seamguard® (W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc.) reinforcement, are used to transect the lateral stomach to create a vertical gastrectomy. Before each firing, adequate tension is ensured to avoid excess tissue under the sleeve that is measured against a 34-Fr bougie. A small margin of gastric tissue is left at the angle of His. Once the gastrectomy is complete, the endoscope is inserted into the oral cavity, down the esophagus, and into the vertical stomach. Air is insufflated, and irrigation is sprayed upon the staple line to check for leaks. The staple line is then reinforced with Tisseel® glue (Baxter International, Inc.). The gastric remnant is removed through the left lower quadrant port after placing fascial stitches. A Blake® drain is placed and brought out through the right upper quadrant port incision.

Postoperative Care

We have a comprehensive multidisciplinary Center of Excellence led by a single surgeon. The surgeon operates with a physician assistant as first assist and a consistent core of surgical techs. Follow-up appointments with complete lab assessments are done routinely at 1 week, 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year, 18 months, and 2 years post-operation. Patients are then seen annually or more frequently if desired. Nutrition classes led by a registered dietitian occur both before and after surgery through 1 year post-operation. A psychological assessment is completed on each patient prior to surgery with multiple social worker led support groups each month.

A UGI is completed on post-operation day (POD) 1 to evaluate the staple line before the advancement of diet. Diet then follows that of RYGB starting with clear liquids on POD 1. On POD 3, liquid protein begins, which continue for 3 weeks, followed by soft protein diet for 5 weeks, and eventually solid protein diet by 8 weeks as tolerated. A proton pump inhibitor is given 3–6 months postoperatively along with MVI, B12, and calcium. Chewable forms of vitamins are encouraged until 3 months post-op.

Results

The mean postoperative percent excess weight loss (%EWL) was 49.9% (n = 159), 64.2% (n = 138), 67.9% (n = 77), 62.4% (n = 34), and 62.2% (n = 9) at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively (Fig. 1). Upon further evaluation, those LSG patients with BMI 35.0–43.0 kg/m2 had similar mean postoperative %EWL to the established averages of LRYGB [19]. For patients with BMI 35.0–43.0 kg/m2, the mean postoperative %EWL was 58.9% (n = 72), 74.1% (n = 67), 75.8% (n = 39), 72.1% (n = 17), and 78.7% (n = 5) at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of %EWL between LSG and LRYGB

Fig. 2.

Comparison of %EWL between LSG and LRYGB for BMI 35.0–43.0 kg/m2

LSG has a significant effect on the resolution or improvement of comorbidities (Table 1). The rates for early complications were 0.0% for leaks, 0.5% for abscess, 1.0% for hemorrhage, and 1.0% for sleeve stricture. The complication rate for severe gastroesphogeal reflux disease (GERD) with need to convert to laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is 0.5%.

Table 1.

Comorbidities Resolved or Improved Post-operation LSG

| Comorbidity | Number of patients | Cases resolved and improved | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 119 | 81 resolved, 35 improved | 97.5 |

| Diabetes | 58 | 41 resolved, 16 improved | 98.3 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 98 | 47 resolved, 48 improved | 96.9 |

| Depression | 103 | 41 resolved, 61 improved | 99.0 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 73 | 53 resolved, 18 improved | 97.3 |

| GERD | 113 | 43 resolved, 69 improved | 99.1 |

| Arthritis | 72 | 37 resolved, 34 improved | 98.1 |

| Chronic joint pain | 44 | 26 resolved, 18 improved | 100.0 |

| Stress incontinence | 44 | 41 resolved, 3 improved | 100.0 |

| Asthma | 34 | 21 resolved, 13 improved | 100.0 |

Discussion

With data collected from 204 patients of a single surgeon, we present one of the largest series of LSG intended as a primary bariatric procedure in morbid obesity. Limitations of our study are that it is nonrandom and retrospective. Because different techniques for surgery exist across the bariatric discipline, standardization is difficult. In our Center of Excellence, we have standardized the LSG technique with respect to surgical procedure, such as narrowness of the gastric sleeve and abdominal access, as well as patient education and support. Regardless of the technique, maximizing patient education and support is critical.

With our standardized technique, it is possible to compare to the gold standard, LRYGB. Although our center's LRYGB data is unpublished, we can compare the results of LSG to LRYGB because these patients follow the same pre- and post-operation multidisciplinary programs, led by the same surgeon and bariatric team (Table 2; Fig. 1 and 2). Of note, our 12 months mean %EWL for LRYGB of 72.4% is comparable to meta-analysis reports of 61.6% [19].

Table 2.

Comparison of LSG to LRYGB

| LSG | LRYGB | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 204 | 1,912 |

| Age at surgery (years) | 45.0 | 49.6 |

| OR time | 92 ± 32 min | 105 ± 29 min |

| Pre-op Wt (kg) | 126.6 | 136.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 45.7 | 49.6 |

| LOS (days) | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| %EWL at 12 months | 67.9% (n = 77) | 72.4% (n = 1,138) |

When compared to LRYGB, benefits include no dumping, a decreased occurrence of vitamin deficiencies, and no interference with medication absorption. LSG is a viable procedure for those patients with extensive adhesions, inflammatory bowel syndrome, and long-term need for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [20, 21]. Complication rates are lower with LSG with no risk of internal hernia or anastomotic issues such as stricture or ulcer [22]. In addition, LSG affords convertibility to a second procedure if suboptimal weight loss is achieved.

LSG is often approved by insurance providers for BMI >50.0 kg/m2, exclusively for super-obese patients as the first step of a staged procedure. However, our results indicate that LSG is an effective primary procedure especially for the lower BMI population (35.0–43.0 kg/m2). This population often looks to laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) because they have less weight to lose, and the procedure is less invasive. However, the LAGB—for which insurance companies approve—introduces a foreign body, requires adjustments, results in lower %EWL, and does not decrease plasma ghrelin levels [15].

Conclusion

LSG yields excellent outcomes with low complication rates for morbidly obese patients. It has many significant advantages over other surgical bariatric treatments. We advocate the LSG as a safe and effective stand-alone procedure, especially with the lower BMI population (BMI 35.0–43.0 kg/m2).

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Brian Gluck, Email: bgluck@aol.com.

Blake Movitz, Email: blakemovitz@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Marceau P, Biron S, Bourque RA, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with a new type of gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 1993;3:29–35. doi: 10.1381/096089293765559728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 1998;8(3):267–282. doi: 10.1381/096089298765554476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu CA, Gagner M, Quinn T, et al. Two-stage laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: an alternative approach to super-super morbid obesity (abstract) Surg Endosc. 2002;16:S069. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regan JP, Inabnet WB, Gagner M, et al. Early experience with two-staged laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obes Surg. 2003;13:861–864. doi: 10.1381/096089203322618669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottam D, Qureshi FG, Mattar SG, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk patients with morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mongol P, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial bariatric operation for high-risk patients: initial results in 10 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1030–1033. doi: 10.1381/0960892054621242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Vertical gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 216 patients: report of two-year results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1810. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baltasar A, Serra C, Perez N, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a multi-purpose bariatric operation. Obes Surg. 2005;15(8):1124–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Han MS, Kim WW, Oh JH. Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at 1 year in morbidly obese Korean patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1469–1475. doi: 10.1381/096089205774859227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franz FX, Langer F, Shakeri-Manesch S, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an isolated bariatric procedure: intermediate-term results from a large series in three Austrian centers. Obes Surg. 2008;18:814–818. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner RA, Weiner S, Pomhoff I, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—influence of sleeve size and resected gastric volume. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1297–1305. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmichael AR, Johnston D, Barker MC, et al. Gastric emptying after a new, more physiological anti-obesity operation: the Magenstrasse and Mill procedure. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1379–1383. doi: 10.1007/s002590100579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston D, Dachtler J, Sue-Ling HM, et al. The Magenstrasse and Mill operation for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2003;13:10–16. doi: 10.1381/096089203321136520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ariyasu H, Takaya K, Tagami T, et al. Stomach is a major source of circulating ghrelin, and feeding state determines plasma ghrelin-like immunoreactivity levels in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4753–4758. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.10.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer FB, Reza Hoda MA, Bohdjalian A, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric banding: effects on plasma ghrelin levels. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1024–1029. doi: 10.1381/0960892054621125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings DE. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubino F, Gagner M. Weight loss and plasma ghrelin levels. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1379–1381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200210243471718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-yy levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401–407. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156f012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1736. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Indications for sleeve gastrectomy as a primary procedure for weight loss in the morbidly obese. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:662–667. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roa PE, Kaidar-Person O, Pinto D, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as treatment for morbid obesity: technique and short-term outcome. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1323–1326. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakdawala MA, Bhasker A, Mulchandani D, et al. Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1 year study. Obes Surg. 2009;20:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9981-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]